Summary

Diabetes is a rapidly increasing disease that enhances the chances of heart failure 2–4 folds (as compared to age and sex matched non-diabetics) and becomes a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. There are two broad classifications of diabetes: type1 diabetes (T1D) and type2 diabetes (T2D). There are several mice models that mimic both T1D and T2D in humans. However, the genetic intervention to ameliorate diabetic cardiomyopathy in these mice often requires creating double knockout (DKO). In order to assess the therapeutic potential of a gene, that gene is either overexpressed (transgenic expression) or abrogated (knockout) in the diabetic mice. If the genetic mice model for diabetes is used, it is necessary to create DKO with transgenic / knockout of the target gene to investigate the specific role of that gene in pathological cardiac remodeling in diabetics. One of the important genes involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling in diabetes is matrix metalloproteinase-9 (Mmp9). Mmp9 is a collagenase that remains latent in healthy hearts but induced in diabetic hearts. Activated Mmp9 degrades extracellular matrix (ECM) and increases matrix turnover causing cardiac fibrosis that leads to heart failure. Insulin2 mutant (Ins2+/−) Akita is a genetic model for T1D that becomes diabetic spontaneously at the age of 3–4 weeks and show robust hyperglycemia at the age of 10–12 weeks. It is a chronic model of T1D. In Ins2+/− Akita, Mmp9 is induced. To investigate the specific role of Mmp9 in diabetic hearts, it is necessary to create diabetic mice where Mmp9 gene is deleted. Here, we describe the method to generate Ins2+/− /Mmp9−/− (DKO) mice to determine whether the abrogation of Mmp9 ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Keywords: Ins2+/− Akita, Mmp9, diabetes, heart failure, cardiomyopathy

1. Introduction

The alarming rate of diabetics [1] and its impact on cardiovascular diseases [2–8] make it a greatest challenge for medical sciences. Diabetes is a global menace [9, 10] that requires global attention. T1D are typically present in the young (therefore also called juvenile diabetes). It is caused either due to mutation of insulin gene that impairs glucose metabolism [11] or developed as an autoimmune disease, where pancreatic beta cells are targeted and destroyed by immune cells [12, 13]. The beta cells are responsible for producing insulin that regulate glucose metabolism. After food intake, blood glucose level increases that triggers signals to release insulin from pancreatic beta cells. Insulin activates Insulin receptor signaling that removes excess glucose from the blood into different cells in body using glucose transporter (GLUT4). It also helps in glucose metabolism (Figure 1). When beta cells are less or absent due to either genetic mutation or autoimmune destruction, the insulin released in response to high blood glucose level is either too less or absolutely absent. This causes low levels of insulin and high levels of glucose in the blood, a signature of T1D (Figure 1). T1D is less prevalent (~5%) in the USA population [14, 15]. Insulin injection before meal is the only clinical treatment practiced for regulating hyperglycemia in T1D patients [12]. Insulin injection sometimes causes hypoglycemia and fluctuation of hyper-to-hypo-glycaemia has devastating impact on different organs including the heart. Heart is a sophisticated but vulnerable organ and diabetes increases the incidence of heart failure [5, 16, 17]. Therefore, investigating an intervention tool to mitigate diabetic cardiomyopathy is indispensable.

Figure 1:

Schematics showing the process of glucose metabolism and their dysfunction in T1D and T2D.

T2D results due to insulin insensitivity or resistance and is more prevalent (~90%) [18–21]. In T2D, although beta cells release insulin in response to elevated blood glucose level, insulin is unable to trigger GLUT4 due to defective insulin receptor signaling that results into increased level of glucose in the blood (Figure1). High level of blood glucose triggers beta cells to constantly release insulin; the insulin level becomes high in blood. Therefore, T2D is diagnosed by increased levels of both glucose and insulin. Chronic T2D puts extensive workload on beta cells to secrete insulin that ultimately causes their death. Therefore, long-term T2D leads to T1D.

We have reported that diabetes induces Mmp9 [22, 23] that in turn impairs contractility of cardiomyocytes [24], induces cardiac fibrosis [23, 25] and differentially express several miRNAs [24] that regulates cardiac functions. Recently, we have demonstrated that Mmp9 is also involved in cardiac stem cell survival and may be involved in their differentiation into cardiomyocytes [25, 26]. We also found that ablation of Mmp9 mitigates cardiac fibrosis [25]. Clinical study demonstrates that MMP9 (human matrix metalloproteinase-9) decreases survival probability and exacerbates mortality in heart failure patients with diastolic dysfunction [27]. Mmp9 is also implicated in hypertension and left ventricle remodeling [28–31]. Ablation of Mmp9 decreases the infarct size in ischemia-reperfusion injury [32].

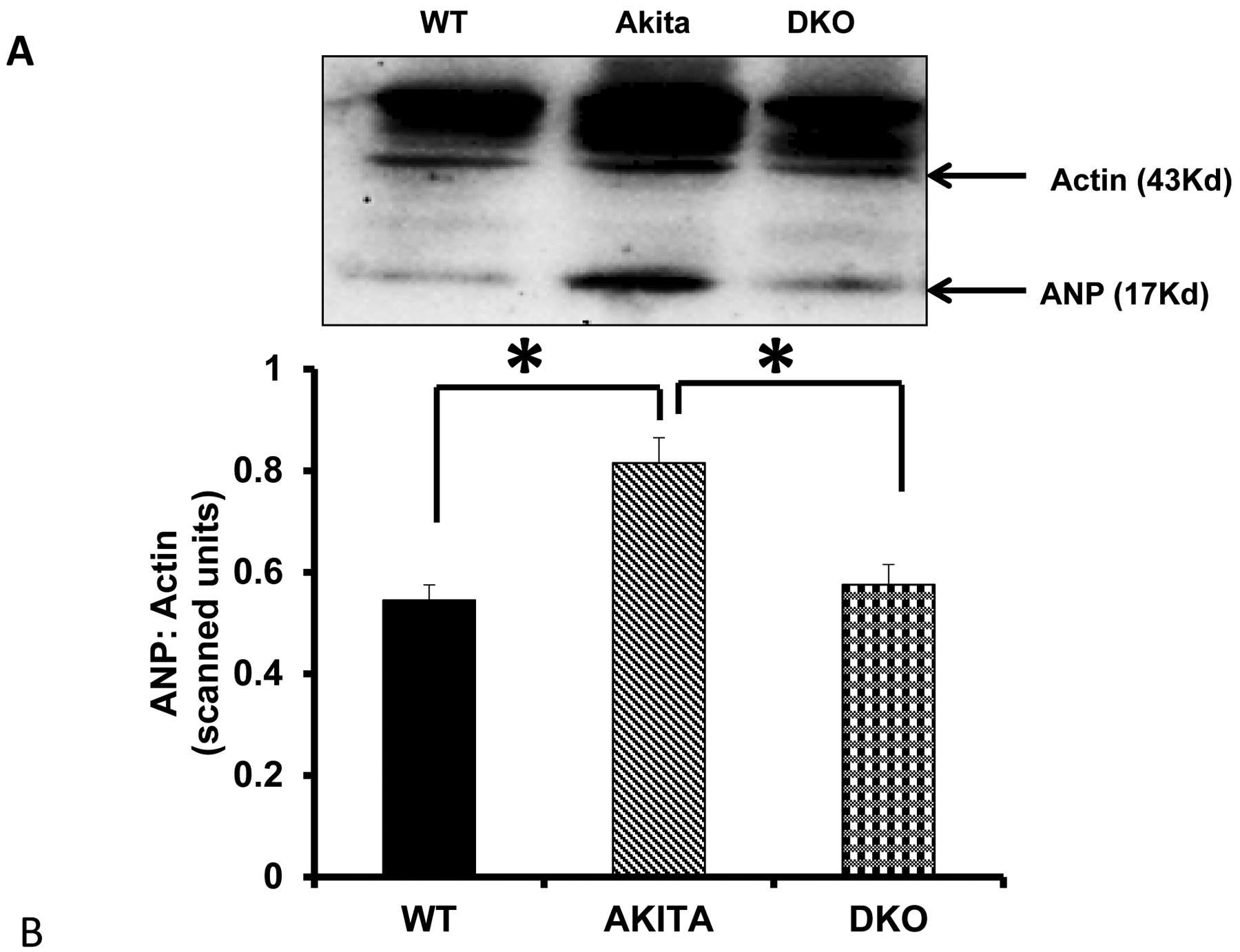

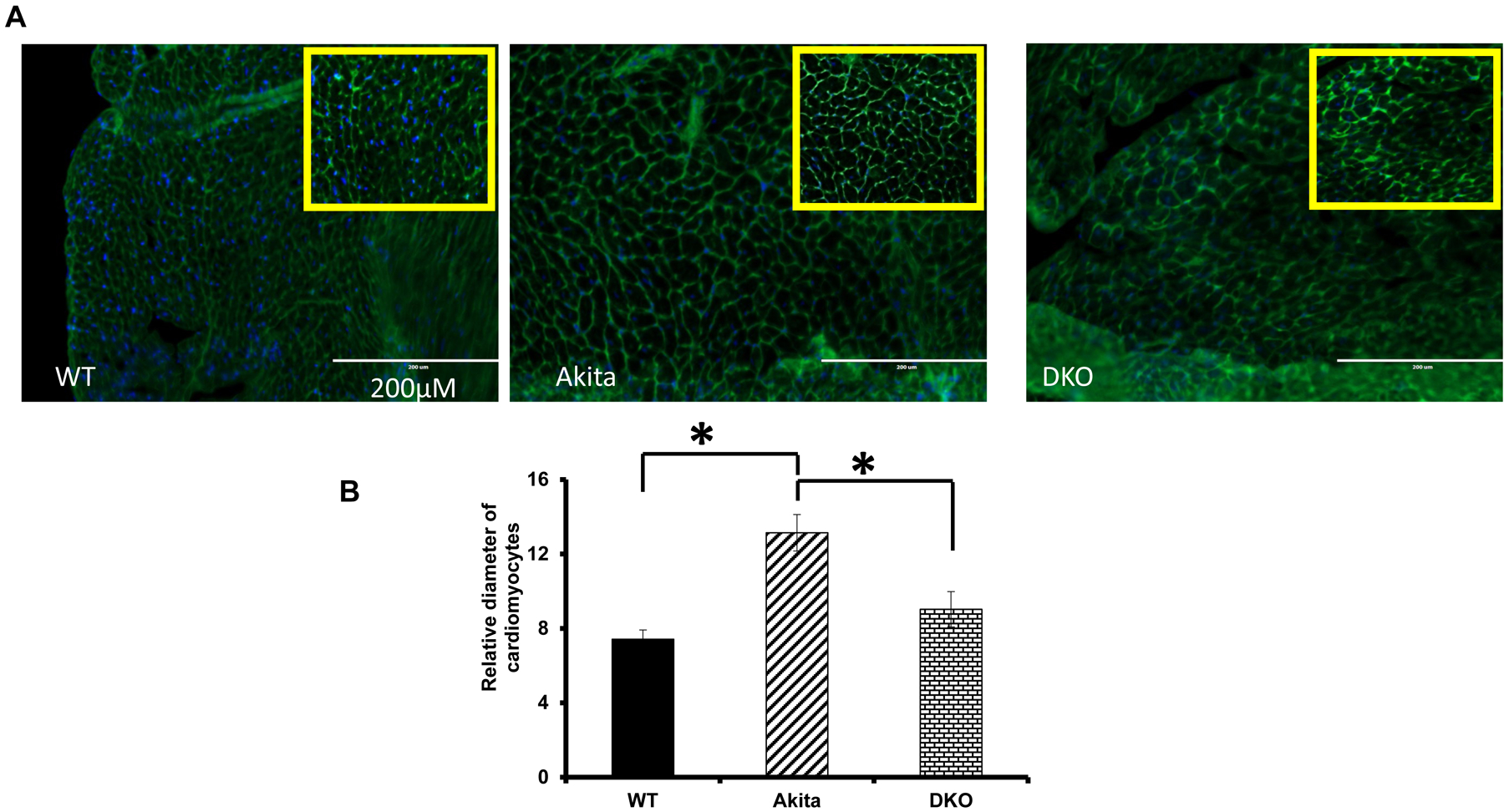

Since Mmp9 is up regulated in diabetic hearts [23], we created DKO (Ins2+/− /Mmp9−/−) mice, where Insulin gene is mutated (T1D) and Mmp9 gene is deleted to assess the specific role of Mmp9 in diabetic cardiomyopathy. The process of generating DKO can be used for combination of other genes. After validating the expression of Mmp9 by genotyping, in-gel-gelatin zymography and immunohistochemistry; cardiac fibrosis was determined in the three groups: WT, Ins2+/− and Ins2+/− MMP9-/−. Interestingly, fibrosis was significantly decreased in Ins2+/− /Mmp9−/− as compared to the Ins2+/− hearts [25]. We also determined the mitigation of cardiac dysfunction in DKO mice by measuring the levels of atrial natriuretic peptide (a marker of cardiac hypertrophy) (Figure 4). The hypertrophy can also be observed by staining the cell membranes with wheat germ agglutinin (Invitrogen) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

The expression of Atrial Natriuretic Peptide (ANP) in the hearts of WT, Akita, and double knockout (DKO) mice. A) Representative bands (Western blot) for the expression of ANP and Actin (loading control). B) Bar graph showing the relative expression of ANP in the three groups. N=3, *p<0.05.

Figure 5. A.

Fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, green color) is used to demarcate cell boundaries as it stains cell membrane. DAPI (blue) is used to stain cell nuclei. The transverse sections of hearts of WT, Akita and DKO mice are used. B. Bar graph showing diameter of the cardiomyocytes, which is used to measure cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, *, p<0.05.

2. Materials

Mice should be ordered from authorized vendor such as Jackson Laboratory.

Mice: Ins2+/− Akita The Jackson Lab stock number is 003548 and the genetic background is C57BL/6J) and Mmp9−/− (The Jackson Lab stock number is 007084 (B6.FVB (Cg)-Mmp9tm1Tvu/J.

Glucose measurement: Glucometer, glucose strips.

Genotyping: Scissors, Ice cold ethanol (see Note 1), DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, USA).

Nanodrop for measuring quality and quantity of DNA, PCR instrument, PCR master mix, primers for Insulin and Mmp9 gene, nuclease free water, Agarose powder (Sigma,USA) TAE buffer (BioRad, USA), Ethidium bromide (Invitrogen, USA), Gel apparatus, BioRad ChemiDoc instrument (Note 2).

0.1% gelatin (Sigma, USA)

3. Methods

3.1. Cross –breeding of Ins2+/– and Mmp9−/− to create Ins2+/− /Mmp9−/−

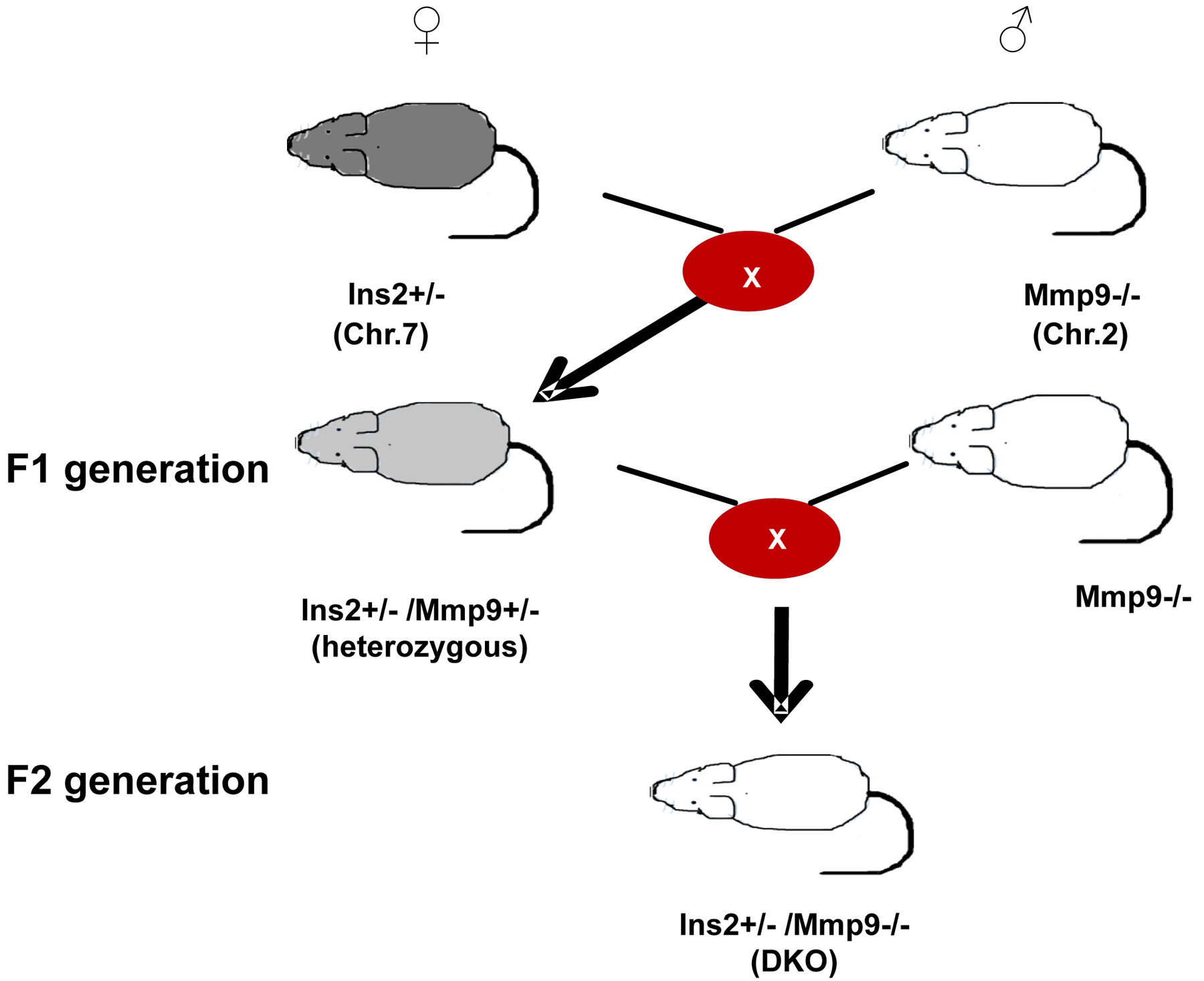

In mouse, there are two Insulin genes (Insulin 1 and Insulin 2) but in human, only one Insulin gene is present. Insulin2 gene of mouse is orthologous to human Insulin and mutation of this gene causes T1D. Insulin gene is located on chromosome 7 whereas Mmp9 gene is located on chromosome 2. After genotyping mice, Ins2+/− females are crossbred with Mmp9−/− male (female: male= 2:1). Since Ins2+/− is heterozygous, the two alleles are different (+ and −). In F1 generation, the two alleles of Ins2+/− are hybridized with one allele (+) of Mmp9 to make two types of genotypes (+/+) and (+/−). For Mmp9 gene there is only “+” allele in Ins2+/− Akita and “-” allele in Mmp9−/− mice and in F1 hybrids only one genotype “+/−” are present. There are two genotypes for F1 hybrids: Ins2+/+ / Mmp9+/− and Ins2+/− /Mmp9+/−. The Ins2+/− /Mmp9+/− heterozygous females are selected for backcrossing with Mmp9−/− males. There are “+” and “-”alleles for both Ins2 and Mmp9 genes in the Ins2+/ /Mmp9+/− hybrids. In F2 generation, the genotypes are “Ins2+/+ / Mmp9+/−”, “Ins2+/− / Mmp9+/−”, “Ins2+/− / Mmp9−/− (DKO)”. The scheme of generating DKO mice is given in Figure 2. The DKO are validated by genotyping as well as expression assay. For MMP9 activity, gelatin zymography are performed. Mmp9 expression is also validated at immunohistochemistry level by measuring fluorescence intensity [25].

Figure 2:

Scheme for generating Ins2+/− /Mmp9−/− (DKO) from Ins2+/− and Mmp9−/− mice.

3.2. Genotyping of Ins2+/–, Mmp9−/− and Ins2+/− /Mmp9−/− mice

3.2.1. DNA extraction

DNA is extracted from the tail of WT, Akita, and DKO mice following the manufacturer’s protocol for the kit

Cut 0.4–0.6 cm length of mouse tail and store it in −20°C until DNA extraction

Mix 180 μL buffer ATL and 20 μL of proteinase K, which are supplied with the kit, and incubate at 56 °C under rotation for overnight or until completely lysed.

For each tail, add 410 μL of buffer AL – ethanol (205 μL AL + 205 μL ethanol) and mix by vortexing.

Transfer the mixture to a DNeasy Mini spin column in a 2 mL collection tube and centrifuge at 3300g for 10 min.

Discard the collection tube and the flow-through, and place the column in a new 2 mL collection tube.

Add a volume of 500 μL AW1 buffer to the spin column and centrifuge at 3300g for 5 min.

Discard the flow through and the collection tube, and the column is placed into a new collection tube.

Add the same volume (500 μL) of AW2 buffer to the column and centrifuged at 3300g for 15 min.

-

After discarding the flow through and the collection tube, place the column into another new collection tube, and add 200 μL of AE buffer for elution. Incubate it for 1 min at room temperature and then centrifuge for 2 min at 3300g.

The flow through (DNA) was collected and stored at –20 °C for polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

3.2.2. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

For genotyping the Insulin2 and Mmp9 mutants, follow the PCR primers and programs from the Jackson Laboratory protocols.

For Insulin 2 gene, the following primers can be used: forward, 5′-TGC TGA TGC CCT GGC CTG CT-3′; and reverse, 5′-TGG TCC CAC ATA TGC ACA TG- 3′.

The PCR program is : 94 °C, 3 min; 94 °C, 20 s; 64 °C, 30 s; decrease in temperature of –5 °C per cycle; 72 °C, 35 s; repeat steps for 12 cycles, 94 °C, 20 s; 58 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 35 s; repeat steps for 25 cycles; 72 °C, 2 min; 10 °C, hold.

For Mmp9 gene, 4 set of primers: 2 sets for the mutant, and 2 sets for wild type gene. The primers for the mutant gene as follows: forward, 5′- CTG AAT GAA CTG CAG GAC GA-3′; and reverse, 5′-ATA CTT TCT CGG CAG GAG CA-3′.

For wild type gene of Mmp9, the primers are: forward, 5′-GTGGGACCA TCA TAA CAT CAC A-3′; and reverse, 5′-CTC GCG GCA AGT CTT CAG AGT A-3′. The cycling conditions are as follows: 94 °C, 3 min; 94 °C, 30 s; 66 °C, 1 min; 72 °C, 1 min; repeat steps for 35 cycles; 72 °C, 2 min; 10 °C, hold.

3.2.3. Agarose gel electrophoresis

Separate the PCR product by electrophoresis using 1.5% Agarose gel, and ethidium bromide (0.008%) and visualize the bands under UV light.

For 100ml of 1.5% Agarose gel, weigh 1.5 g of Agarose and dissolve in 1X TAE buffer and boil it for 2 min.

Allow it to cool down to ~ 60°-70°C and then add 8μl of ethidium bromide.

Pour the solution into the Agarose gel cast and allow it to solidify.

Perform gel electrophoresis in 1X TAE buffer at 70V.

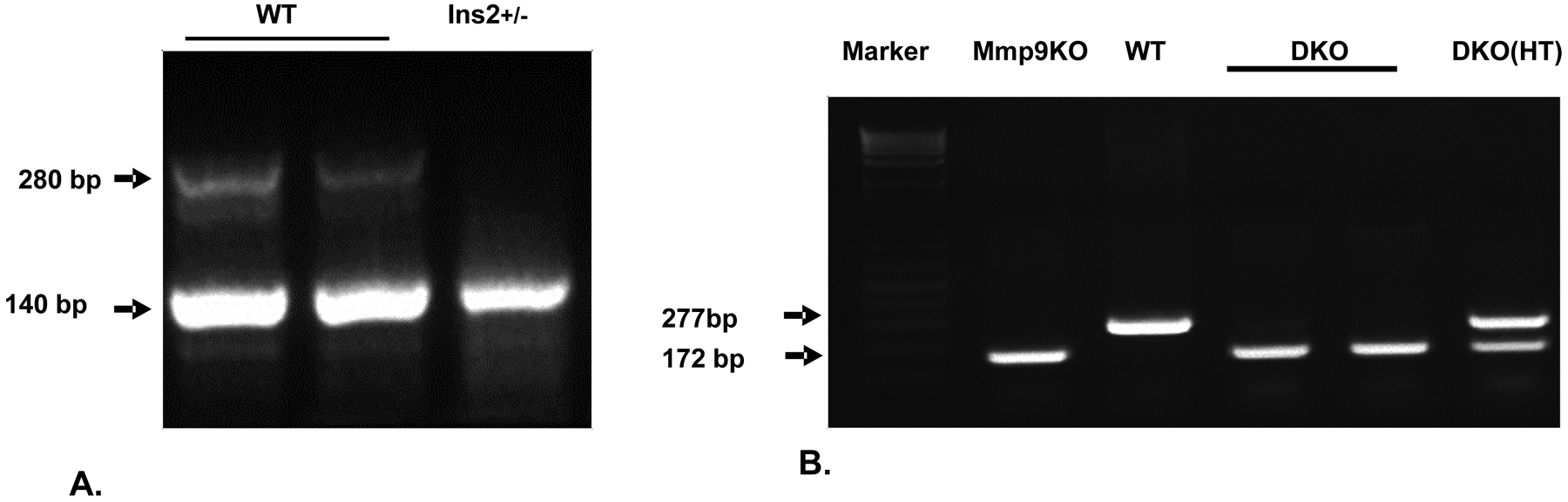

3.2.4. Analyses of bands

In Akita mice, Insulin2 gene is heterozygous. The Insulin2 gene amplification product will show 2 bands of 140 and 280 base pairs.

The WT mice will have only 140 bp band.

In DKO (Ins2+/− /Mmp9−/−) mice, the PCR product for Mmp9 gene primer will show single band at 172 bp.

In WT mice, there will be single Mmp9 band of 277 bp, whereas in heterozygous mice there will be 2 bands of 172 and 277 bp [25] (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

The genotypes of WT, Akita, Mmp9+/− and Mmp9−/− mice.

A) PCR amplification of Insulin2 gene showing two bands in WT (Ins2+/+) and one band in Ins2+/− mice.

B) PCR amplification of Mmp9 gene showing genotypes for Mmp9 knock out (Mmp9KO), WT (Mmp9+/+), double knockout homozygous (DKO) (Ins2+/− /Mmp9−/−) and DKO heterozygous (Ins2+/− /Mmp9+/−HT) mice.

3.3. In-gel-gelatin zymography

Prepare SDS –substrate PAGE with gels with 0.1% gelatin in both the stacking and resolving gels.

To prepare the 0.1% gelatin solution, weigh 0.1g of gelatin and dissolve in 100ml of distilled water. Gelatin will not be dissolve at room temperature. Heat the solution to 50–60°C until the gelatin is completely dissolved (Note 3).

Cool down the solution to room temperature and prepare the SDS PAGE gel with stacking (4–5%) and resolving (7.5–10%) gels, in place of water use this 0.1% gelatin solution.

For sample preparation, take the desired concentration of protein and add 2x sample buffer (0.5M Tris HCl, pH 6.8– 2.5 ml; Glycerol- 2.0ml ; 10% SDS −4ml, 0.1% bromophenol blue- 0.5ml and make up the final volume to 10 ml with distilled water).

Mix the protein and 2X sample buffer and keep it at room temperature for 10 minutes (Note 4).

Load 10–30μl protein samples and perform gel electrophoresis in 1X Tris-Glycine-SDS running buffer at 70 V.

Once the tracking dye passes through the bottom of gel, remove the resolving gel and wash it in distilled water.

Incubate the resolving gel in 1X re-naturing buffer (Triton × 100 – 2.5% v/v in distilled water) with gentle shaking for 30 minutes. Repeat this step two times, and each time use fresh re-naturing buffer.

After this, keep the gels in 1X developing buffer (Tris base 1.21 g, Tris HCl-6.3g, Nacl −11.7g, CaCl2 −0.74, Brij 35–0.02% in 1 L of distilled water) at 37°C at slow shaking for 48 hours.

Wash the gels with distilled water and stain the gels with Coomassie blue R-250 (0.5% w/V in methanol) for 30 minutes.

To see the clear bands wash the gels with distilled water.

De-staining solution (30% methanol and 10% v/v acetic acid) can also be used to remove the excess stain of the gel.

Gelatinase activity could be seen in any Gel Doc instrument with UV light as cleared (unstained) regions on the blue background.

3. Notes

When genotyping is done in 10–21 days old mice, ice cold ethanol is used as local anesthesia before clipping 1–2 mm tail.

Any Gel Doc instrument with UV light will serve the purpose.

Excessive heat or boiling of sample may degrade gelatin. Since gelatin is the substrate for Mmp9, it is necessary to dissolve the gelatin without boing it.

The samples should not be boiled as it alters the quaternary structure of protein and impairs the enzymatic activity of Mmp9.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by National Institute of Health grants HL-113281 and HL116205 to Paras Kumar Mishra.

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H (2004) Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 27:1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chavali V, Tyagi SC, Mishra PK (2013) Predictors and prevention of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 6:151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew V, Gersh BJ, Williams BA, Laskey WK, Willerson JT, Tilbury RT, Davis BR, Holmes DR Jr. (2004) Outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the current era: a report from the Prevention of REStenosis with Tranilast and its Outcomes (PRESTO) trial. Circulation 109:476–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignone M, Alberts MJ, Colwell JA, Cushman M, Inzucchi SE, Mukherjee D, Rosenson RS, Williams CD, Wilson PW, Kirkman MS (2010) Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association, a scientific statement of the American Heart Association, and an expert consensus document of the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Diabetes Care 33:1395–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rota M, LeCapitaine N, Hosoda T, Boni A, De AA, Padin-Iruegas ME, Esposito G, Vitale S, Urbanek K, Casarsa C, Giorgio M, Luscher TF, Pelicci PG, Anversa P, Leri A, Kajstura J (2006) Diabetes promotes cardiac stem cell aging and heart failure, which are prevented by deletion of the p66shc gene. Circ Res 99:42–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, Gobin R, Kaptoge S, Di AE, Ingelsson E, Lawlor DA, Selvin E, Stampfer M, Stehouwer CD, Lewington S, Pennells L, Thompson A, Sattar N, White IR, Ray KK, Danesh J (2010) Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 375:2215–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schramm TK, Gislason GH, Kober L, Rasmussen S, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, Hansen ML, Folke F, Buch P, Madsen M, Vaag A, Torp-Pedersen C (2008) Diabetes patients requiring glucose-lowering therapy and nondiabetics with a prior myocardial infarction carry the same cardiovascular risk: a population study of 3.3 million people. Circulation 117:1945–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spencer EA, Pirie KL, Stevens RJ, Beral V, Brown A, Liu B, Green J, Reeves GK (2008) Diabetes and modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the prospective Million Women Study. Eur J Epidemiol 23:793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman WH, Zimmet P (2012) Type 2 diabetes: an epidemic requiring global attention and urgent action. Diabetes Care 35:943–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH (1998) Global burden of diabetes, 1995–2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care 21:1414–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoy J, Edghill EL, Flanagan SE, Ye H, Paz VP, Pluzhnikov A, Below JE, Hayes MG, Cox NJ, Lipkind GM, Lipton RB, Greeley SA, Patch AM, Ellard S, Steiner DF, Hattersley AT, Philipson LH, Bell GI (2007) Insulin gene mutations as a cause of permanent neonatal diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:15040–15044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang CL, Chen YC, Chen HM, Yang NS, Yang WC (2013) Natural cures for type 1 diabetes: a review of phytochemicals, biological actions, and clinical potential. Curr Med Chem 20:899–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simsek DG, Aycan Z, Ozen S, Cetinkaya S, Kara C, Abali S, Demir K, Tunc O, Ucakturk A, Asar G, Bas F, Cetinkaya E, Aydin M, Karaguzel G, Orbak Z, Siklar Z, Altincik A, Okten A, Ozkan B, Ocal G, Semiz S, Arslanoglu I, Evliyaoglu O, Bundak R, Darcan S (2013) Diabetes care, glycemic control, complications, and concomitant autoimmune diseases in children with type 1 diabetes in Turkey: a multicenter study. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 5:20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishra PK, Singh SR, Joshua IG, Tyagi SC (2010) Stem cells as a therapeutic target for diabetes. Front Biosci 15:461–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nokoff NJ, Rewers M, Cree GM (2012) The interplay of autoimmunity and insulin resistance in type 1 diabetes. Discov Med 13:115–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masoudi FA, Inzucchi SE (2007) Diabetes mellitus and heart failure: epidemiology, mechanisms, and pharmacotherapy. Am J Cardiol 99:113B–132B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Kumar M, Tyagi SC (2009) MicroRNAs as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. J Cell Mol Med 13:778–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agyemang C, Kunst AE, Bhopal R, Zaninotto P, Nazroo J, Unwin N, van V,I, Redekop WK, Stronks K (2013) A cross-national comparative study of metabolic syndrome among non-diabetic Dutch and English ethnic groups. Eur J Public Health 23:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barengo NC, Trejo R, Sposetti G (2013) Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Argentina 1979–2012. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. Epub. July 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gable D, Sanderson SC, Humphries SE (2007) Genotypes, obesity and type 2 diabetes--can genetic information motivate weight loss? A review. Clin Chem Lab Med 45:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Q, Wang Y, Huang ES (2009) Changes in racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes by obesity level among US adults. Ethn Health 14:439–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Kundu S, Tyagi SC (2009) MicroRNAs are involved in homocysteine-induced cardiac remodeling. Cell Biochem Biophys 55:153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Sen U, Joshua IG, Tyagi SC (2010) Synergism in hyperhomocysteinemia and diabetes: role of PPAR gamma and tempol. Cardiovasc Diabetol 9:49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra PK, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC (2010) MMP-9 gene ablation and TIMP-4 mitigate PAR-1-mediated cardiomyocyte dysfunction: a plausible role of dicer and miRNA. Cell Biochem Biophys 57:67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra PK, Chavali V, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC (2012) Ablation of MMP9 induces survival and differentiation of cardiac stem cells into cardiomyocytes in the heart of diabetics: a role of extracellular matrix. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 90:353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mishra PK, Kuypers NJ, Singh SR, Leiberh ND, Chavali V, Tyagi SC (2013) Cardiac Stem Cell Niche, MMP9, and Culture and Differentiation of Embryonic Stem Cells. Methods Mol Biol 1035:153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buralli S, Dini FL, Ballo P, Conti U, Fontanive P, Duranti E, Metelli MR, Marzilli M, Taddei S (2010) Circulating matrix metalloproteinase-3 and metalloproteinase-9 and tissue Doppler measures of diastolic dysfunction to risk stratify patients with systolic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 105:853–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradham WS, Moe G, Wendt KA, Scott AA, Konig A, Romanova M, Naik G, Spinale FG (2002) TNF-alpha and myocardial matrix metalloproteinases in heart failure: relationship to LV remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282:H1288–H1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ducharme A, Frantz S, Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Lindsey M, Rohde LE, Schoen FJ, Kelly RA, Werb Z, Libby P, Lee RT (2000) Targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 attenuates left ventricular enlargement and collagen accumulation after experimental myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest 106:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindsey ML, Escobar GP, Dobrucki LW, Goshorn DK, Bouges S, Mingoia JT, McClister DM Jr., Su H, Gannon J, MacGillivray C, Lee RT, Sinusas AJ, Spinale FG (2006) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene deletion facilitates angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290:H232–H239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinale FG (2002) Matrix metalloproteinases: regulation and dysregulation in the failing heart. Circ Res 90:520–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romanic AM, Harrison SM, Bao W, Burns-Kurtis CL, Pickering S, Gu J, Grau E, Mao J, Sathe GM, Ohlstein EH, Yue TL (2002) Myocardial protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Cardiovasc Res 54:549–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]