In December 2019, the World Health Organization office in China was informed of cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology detected in Wuhan.1 A new coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2 was identified in lower respiratory tract samples from several patients. The virus has spread worldwide and on March 11, 2020, was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. From the time of its detection to April 26, 2020, more than 2,900,000 cases have been confirmed worldwide with more than 203,000 deaths. In Colombia, 5379 cases have been confirmed, with 244 deaths reported.2, 3, 4

Healthcare professionals are exposed to contagion as part of their professional practice. World newspapers report high numbers of infections among doctors and an alarming number of deaths. According to data from the British Medical Journal, as of April 5, 2000, 198 physician deaths from COVID-19 had been reported worldwide. Among the countries with the highest mortality are Italy with 73 and Iran with 43 deceased doctors. Among these, the vast majority were men (90%).5

Recently, the Journal of the American Medical Association reported more than 3000 infected health professionals in China, with more than 22 deceased.6 On April 13, the Argentinian newspaper Mundo reported more than 4824 infected physicians in Italy. The New York Times reported on March 24, 2020 that in Spain, the total number of infected individuals exceeded 40,000, with almost 14% (5400) being health professionals. In Colombia, as of April 15, the first 4 physicians have died from COVID-19, and others are still in intensive care. Digestive endoscopic procedures carry a high risk of exposure given the high production of aerosols they generate. A recent study by Johnston et al7 confirmed significant exposure of the endoscopist to potentially infectious biological samples during endoscopy. Although circumstances have not yet allowed studies of endoscopist exposure to COVID-19, the data can be extrapolated to other epidemics. Endoscopy procedures require a short distance between the patient and the doctor; according to studies conducted during the 2003 global SARS outbreak, drops from infected patients could be as much as 6 feet or more from the source.8

Although COVID-19 is widely known as a respiratory virus, there have been reports of patients with GI symptoms that developed before respiratory manifestations. Recent studies of COVID-19 showed GI tropism of the coronavirus, verified by detection of the virus in biopsy specimens and stool, even in discharged patients. This may provide some explanation for the GI symptoms, potential recurrence, and transmission of COVID-19 from individuals who persistently shed the virus.9,10 A study by Chen et al11 analyzed 42 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 and found that 8 (19.05%) had GI symptoms; 28 (66.67%) patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool specimens. Among them, 18 (64.29%) remained positive for viral RNA in feces after pharyngeal swabs returned negative results. The duration of viral shedding from feces after conversion to negative pharyngeal swab results was 6 to 10 days. These findings suggest possible transmission via the fecal–oral route. Although this route of transmission has not been confirmed or refuted, it seems safer to prevent any kind of contamination during lower GI procedures.

This motivates us to seek a new protection barrier for endoscopists to limit contact with aerosols from the patient. We report an economic and easily achievable anti-aerosol barrier design that protects the group involved in upper and lower digestive endoscopy procedures. Although we have not used this barrier in ERCP, we think use is possible—surrounding the head with the barrier while confirming that the oxygen cannula remains in place—if the patient is not under general anesthesia. Cardiopulmonary monitoring is always necessary during any procedure performed with this barrier.

Protection barrier

The following are the steps used in creating the protection barrier:

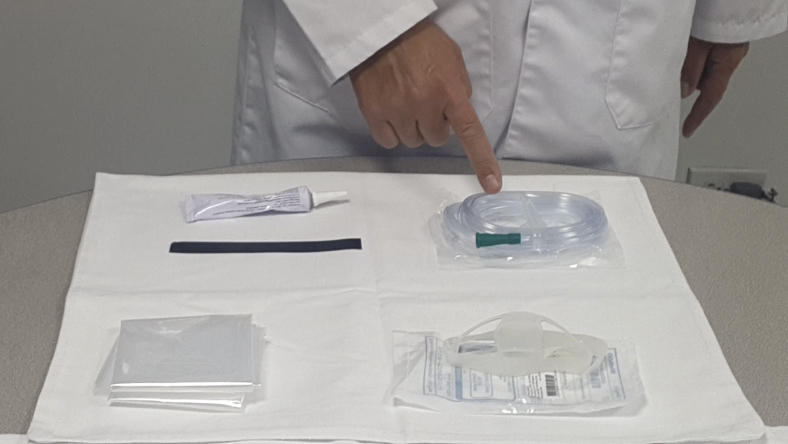

Step 1: Elements of the barrier (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

The elements needed are (1) 75- × 75-cm plastic, (2) 12- to 18-cm tape, (3) lubricant, (4) oral protector for endoscopy, and (5) oxygen cannula. During an upper digestive procedure performed with this barrier, oxygen should always remain on until the barrier is withdrawn.

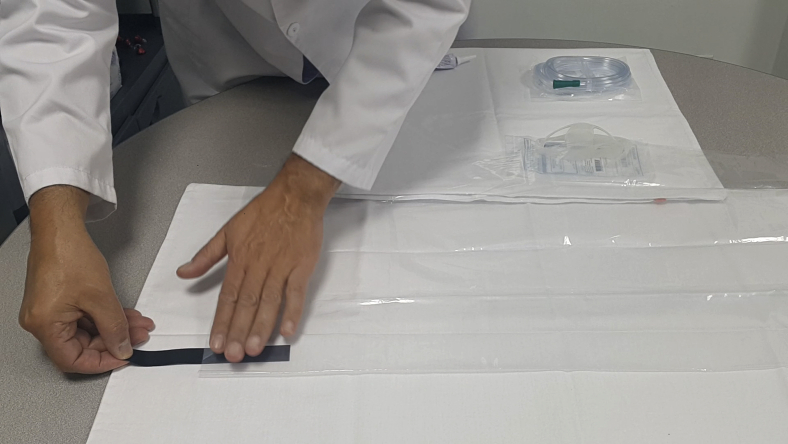

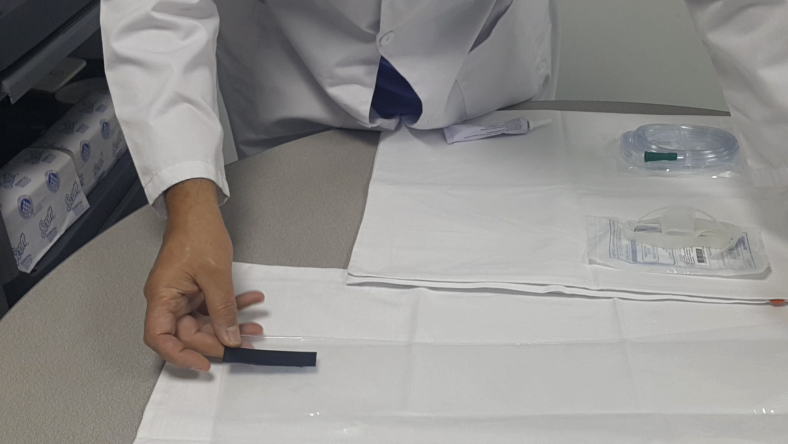

Step 2: Creating the barrier (Figs. 2 and 3)

Figure 2-3.

The 75- × 75-cm plastic is modified by folding it in half and placing a small 12- to 18-mm tape 15 mm from the edge of the fold, creating an entry hole for the endoscope.

Step 3: Lubrication and insertion of the endoscope (Figs. 4 and 5)

Figure 4-5.

Once the tape is placed with the hole created, it is lubricated to facilitate entry of endoscopic equipment.

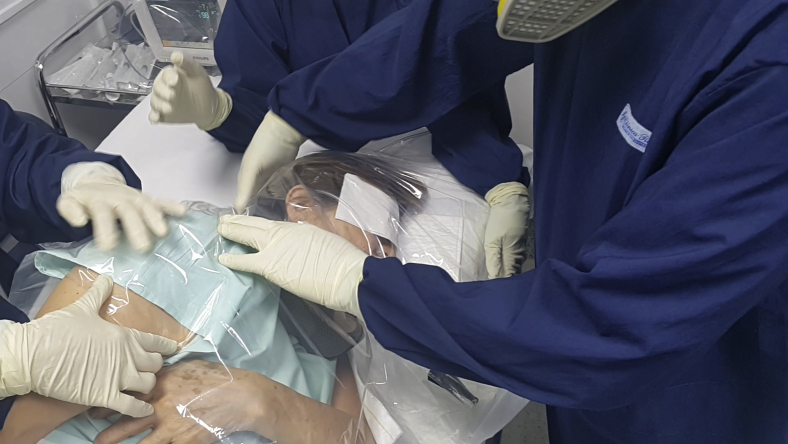

Step 4: Placement of the barrier (Figs. 6 and 7)

Figure 6-7.

After placing the oxygen cannula and the oral protector and explaining the barrier to the patient, the barrier is set on the patient’s head, fixing the posterior edge below the patient’s head and the anterior edge to the anterior end of the stretcher.

Step 5: Starting the procedure (Figs. 8-10)

Figure 8-10.

The previously lubricated endoscope is inserted through the hole created. The nurse assistant fixes the plastic to avoid displacement during the procedure.

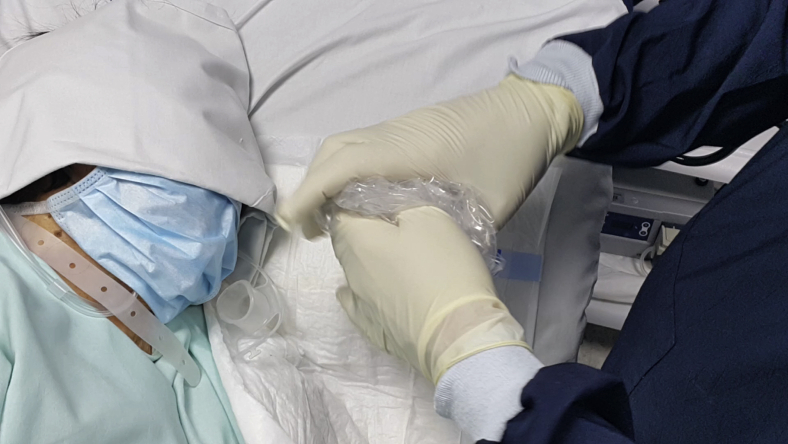

Step 6: Withdrawal and discarding of the barrier (Figs. 11-15)

Figure 11-15.

The barrier should remain in place until the end of the procedure. Aerosols can be seen in the plastic. The oral protector with the plastic in place is removed, and a wrapping maneuver is performed from the front to the back to avoid peripheral contamination. Once a sphere is formed with the plastic, it is covered with the gloves used for the enveloping maneuver and they are discarded. Double gloving is required.

Conclusions

We have reached the following conclusions:

-

1.

Digestive endoscopic procedures involve a high risk of exposure to COVID-19, given their high generation of aerosols.

-

2.

All of the protective equipment described in the personal protection equipment guidelines must be used.

-

3.

The plastic barrier described is a protection method that allows aerosols to be isolated and reduces contamination among the group performing the procedure.

-

4.

The barrier is low cost, easy to install, and can be generalized in all public and private institutions because of its cost effectiveness.

-

5.

The barrier can be used in upper endoscopic procedures, such as EGD, EUS, ERCP, and lower digestive endoscopy procedures.

Disclosure

All authors disclose no financial relationships.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.World Health Organization Pneumonia of unknown cause – China. https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/ Available at:

- 2.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation report – 50. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200310-sitrep-50-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=55e904fb_2 Available at:

- 3.Coronavirus (COVID-2019) en Columbia. https://www.ins.gov.co/Noticias/Paginas/Coronavirus.aspx Available at:

- 4.Repici A, Maselli R, Colombo M. Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: what the department of endoscopy should know. Gastrointest Endosc. Epub 2020 March 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Ing E, Xu A, Salimi A, Torun N. Physician deaths from corona virus disease (COVID-19). Occup Med (Lond). Epub 2020 May 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Adams J.G., Walls R.M. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1439–1440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston E.R., Habib-Bein N., Dueker J.M. Risk of bacterial exposure to the endoscopists face during endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:818–824. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong T.W., Lee C.K., Tam W. Cluster of SARS among medical students exposed to single patient, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:269–276. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung W.K., To K.F., Chan P.K. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome associated coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu J, Han B, Wang J. COVID-19: gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission. Gastroenterology. Epub 2020 Mar 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. Epub 2020 Apr 3. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.