Abstract

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). It emerged as a global pandemic in early 2020, affecting more than 200 countries and territories. The infection is highly contagious, with disease transmission reported from asymptomatic carriers, including children. It spreads through person-to-person contact via aerosol and droplets. The practice of social distancing—maintaining a distance of 1-2 m or 6 ft—between people has been recommended widely to slow or halt the spread. In orthodontics, this distance is difficult to maintain, which places orthodontists at a high risk of acquiring and transmitting the infection. The objective of this review is to report to orthodontists on the emergence, epidemiology, risks, and precautions during the disease crisis. This review should help increase awareness, reinforce infection control, and prevent cross-transmission within the orthodontic facility.

Methods

A comprehensive literature review of English and non-English articles was performed in March 2020 using COVID-19 Open Research Dataset (CORD-19 2020), PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, and Google Scholar to search for infection control and disease transmission in orthodontics.

Results

This review emphasizes minimizing aerosol production and reinforcing strict infection control measures. Compliance with the highest level of personal protection and restriction of treatment to emergency cases is recommended during the outbreak. Surface disinfection, adequate ventilation, and decontamination of instruments and supplies following the guidelines are required.

Conclusions

Reinforcing strict infection control measures and minimizing personal contact and aerosol production are keys to prevent contamination within orthodontic settings. Although no cases of COVID-19 cross-transmission within a dental facility have been reported, the risk exists, and the disease is still emerging. Further studies are required.

Highlights

-

•

Coronavirus disease 2019 is a highly contagious global pandemic.

-

•

It could transmit by asymptomatic carriers via person-to-person contact, aerosol, and droplets.

-

•

Strict infection control and aerosol containment are required in orthodontic settings.

By the end of 2019, an outbreak of severe pneumonia of unknown etiology occurred in Wuhan, China. Bats are believed to be the natural hosts of the disease that was transmitted to humans through an intermediate host.1 Genomic sequencing revealed a pathogen of coronavirus family similar to coronavirus related to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV).2 The new virus was initially referred to as novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV, then as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.3

This virus possesses higher transmissibility potential compared with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, resulting in a “public health emergency crisis of international concern.”4 The infection is believed to transmit to humans through fomites, person-to-person contact, aerosol, and droplets.2 , 5 , 6 The World Health Organization (WHO) declared this viral outbreak a pandemic affecting 693,224 individuals in more than 200 countries and territories, with a total of 33,106 confirmed deaths by March 30, 2020.7 , 8 The highest number of reported cases were in the United States, with the total number doubled in less than 5 days reaching 122,653 confirmed cases.8 , 9 The highest reported deaths were in Italy, reaching 10,781 deaths out of 97,689 confirmed cases with an 11% mortality rate.8 Patients confirmed with coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) develop symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection, including fever, coughing, sneezing, vomiting, generalized fatigue, and severe pneumonia.10 , 11 The disease onset could be mild, moderate, severe, or critical. Symptoms among infected patients vary from being asymptomatic to Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, sepsis, septic shock, and multiple organ failures in critical patients with high reported deaths.12

Several studies have reported cross-transmission of COVID-19 among healthcare workers, including 3,387 confirmed cases and 22 reported deaths.13 The disease can transmit from one healthcare worker to another, healthcare worker to patient, or patient to patient within the same facility.6

Orthodontists may see dozens of patients in a single day. This fact makes strict infection control measures with the highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 an area of concern. Children comprise the vast majority of orthodontic patients. Studies have reported asymptomatic children infected with COVID-19.5 , 14 , 15 The incubation period of this disease is 14 days up to 24 days.10 , 16 The virus is still highly contagious during this latency period.16 This finding rings the alarm bell of a potential hazard: treating asymptomatic patients and spreading infection within the orthodontic clinic. Furthermore, aerosol generation—a routine occurrence in the orthodontic clinic—is a confirmed route of infection transmission.2 , 5

Thus, to face this highly contagious infection, it is important to reevaluate infection control measures within the orthodontic practice. The objective of this review is to shed light on SARS-CoV-2 infection and provide insights on risk, precautions, and recommendations within the orthodontic setting. This review will help increase awareness and control cross-contamination among orthodontists, assistants, office staff, and patients during the COVID-19 crisis.

Material and methods

Considering the recent emergence of COVID-19, this review included publications in English and non-English languages that matched the search terms up to March 19, 2020. Studies were retrieved from the following databases: COVID-19 Open Research Dataset (CORD-19 2020)17 (March 13th, 2020 was the last published update), PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Non-English articles and abstracts were translated.

The main author with the help of a research assistant conducted the search using the following terms: COVID, COVID-19, COVID-2019, 2019-nCoV, SARS-CoV-2, corona, oral, mouth, dental, dentist, dentistry, stomatology, orthodontic, orthodontist, saliva, infection control, contamination, and transmission. Studies included any of the search terms were selected, and duplicates were eliminated. Screening of titles followed by abstracts was performed. Lastly, articles that fall within the scope of this review were included and retrieved in full text. References of those articles were screened as well using the snowballing technique. The findings of the included studies are discussed below.

Literature overview

Risk of disease transmission within the orthodontic practice

Dentistry, including orthodontics, requires proximity to patients while performing operatory procedures. Unfortunately, this makes the dental healthcare workers at a high risk of acquiring infectious diseases.18 The current recommendations for COVID-19 are to avoid person-to-person contact and maintain 1-2 m distance between individuals.6 This recommendation cannot be optimized in the orthodontic clinic for the nature of the orthodontic operation, which places the orthodontist and the dental assistant at a high risk of acquiring the infection.

In addition, the incubation period of 2019-nCoV infection could reach up to 24 days, while still being contagious during this latency period.10 , 16 This is especially important for the orthodontists who tend to see a high volume of patients in a short period daily. Furthermore, several studies reported asymptomatic carriers, including children, who comprise a high percentage of orthodontic patients, which elevates the risk on the orthodontic team even higher.5 , 14 , 19 Although cross-transmission of COVID-19 within a dental facility has not been reported so far, considering the recent onset of the disease and deficiency in data, the risk is still elevated. Previous studies have reported cross-transmission of infection within the dental facilities including Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C.20, 21, 22, 23 In the United States, orthodontists are ranked the second-highest incidence of acquiring Hepatitis B.24, 25, 26

Meng et al27 reported 9 confirmed cases of COVID-19 within dental team members at the School and Hospital of Stomatology, Wuhan University (SHSWH). Although this was possibly an infection from an outside source other than the dental facility, infected personnel could be contagious during their latency period and infect other team members or patients visiting the dental clinic. This possibility brings the importance of taking strict measures to ensure safety and avoid possible transmission within the orthodontic practice.

Possible sources of contamination

-

1.

Patient's saliva: Studies reported high loads of SARS-CoV-2 in the saliva of infected patients.28 Other studies reported large numbers of ACE2 (the receptor for SARS-CoV-2) on the human tongue and buccal mucosa and raised the possibility of oral-fecal transmission.29 , 30 The oral cavity is thus an incubator and a host of disease transmission.6

-

2.

Aerosol: Using a high-speed handpiece or ultrasonic scaler during dental cleaning at bonding, bracket repositioning, and debonding visits produces aerosol and splatter in the operatory vicinity.31 This aerosol could be contaminated with patient's blood, saliva, or high concentrations of infectious microbes exceeding those produced by coughing or sneezing.31, 32, 33 Moreover, aerosol containing microbes was found to reach as far as 2 m from the patient's mouth, with the highest concentrations reported the furthest away from the patient.34 This finding means microbes could contaminate surfaces throughout the operatory. A study performed using a fluorescent dye with a high-speed handpiece found that the fluorescence dye reached more than 2 ft from the dental chair. The dye was even found in the noses of the operator and assistant, having penetrated their facial protective gear.35 Another study reported traces of aerosol were found on operators' scrub jacket sleeves and chest area.36 The aerosol could contaminate the dental unit waterline, resulting in the spread of infection.37 Aerosols containing germs of 0.5-10 μm or less can remain airborne longer, increasing the risk of being inhaled and entering deeper areas of the lung, posing a potential infectious hazard.38 This collectively presents an alarming threat with the highly contagious COVID-19.

-

3.

Orthodontic supplies and instruments: Although most archwires are packaged and sealed individually, some orthodontists have recycled and reused wires.19 , 39 , 40 This is a huge risk of cross-contamination if wires are not thoroughly sterilized. In addition, reusing tried-in orthodontic bands, orthodontic brackets, elastomeric chains, tungsten carbide debonding burs, miniscrews, orthodontic markers, and photographic retractors without proper sterilization and disinfection are tremendous potential hazards.41, 42, 43, 44, 45 Orthodontic instruments that come in direct contact with patients' saliva and blood, including band seaters, band removers, scalers, and ligature directors are considered contamination dangers as well.25 Improper handling and disinfection of such instruments and supplies would compromise infection control measures within the orthodontic practice.

Preventive measures

-

1.

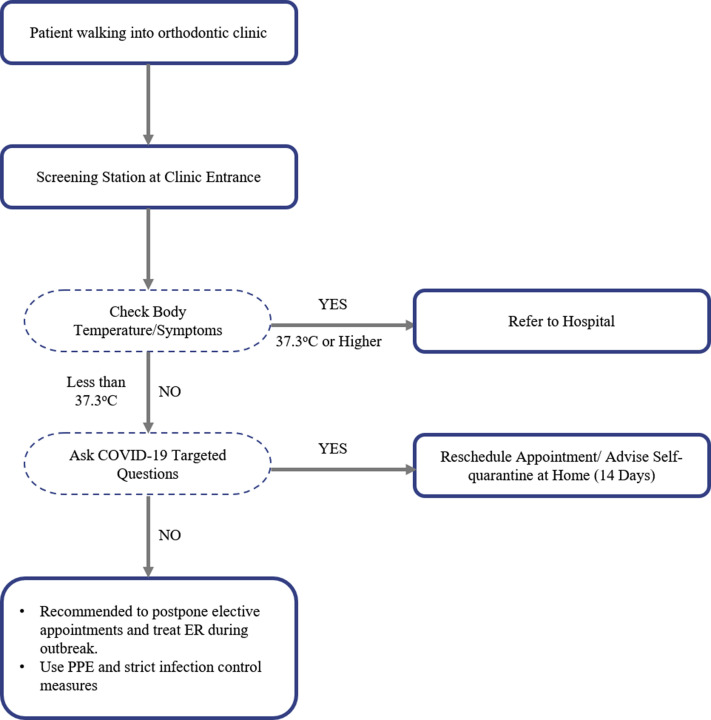

Patient evaluation and screening: In general, it is recommended during the outbreak to postpone any routine appointments and restrict patients' visits to emergency treatment only.27 , 46 Screening patients for COVID-19 symptoms and recording their body temperature is essential.2 , 6 , 47 Updating patient's medical history and asking targeted questions relevant to COVID-19 before initiating any dental work is mandatory.2 This includes (1) history of fever (37.3°C or higher) or use of antipyretic medication in the past 14 days; (2) symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection, including dyspnea in the past 14 days; (3) history of travel to a COVID-19 epidemic area in the past 14 days; and (4) history of contact with a confirmed COVID-19 in the past 14 days.

If the patient is a suspected asymptomatic (no symptoms and no fever), then reschedule the appointment and advise the patient to self-quarantine at home for 14 days. It is unlikely that a confirmed COVID-19 with acute symptoms will visit the orthodontic clinic yet if the patient showed any symptoms, reporting and referral to COVID-19 prepared hospital is mandatory (Fig 1 ).2 , 6 , 47

-

2.

Daily self-evaluation of the dental health care provider is advised. If the orthodontist does not feel well or developed any symptoms, it is prohibited to work and spread infection.48

-

3.

Mouth rinse before any procedure using 0.12%-0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate could help minimize the number of microbes within the oral cavity.6 , 49

-

4.

Personal protective equipment, including facial mask, face shield, eye protection, gowns, and gloves, are essential protective gear during the outbreak.6 , 27 , 48 , 50 COVID-19 was reported to transmit through contact of the virus with ocular mucosa; thus, any contact with mucosal tissue of the eyes, nose, or mouth should be avoided.27 , 51

-

5.

Aerosol production should be restricted, and if necessary, particulate respirators such as N95, EU FFP2, or equivalent in addition to face shield are required.6 , 27 , 48 , 50 Although COVID-19 was categorized as group B infectious disease, the guidelines suggest that healthcare providers perform protective measures similar to those reserved for group A infectious diseases (such as cholera and plague).52

-

6.

Reinforcement of hand hygiene measures according to WHO recommendations (washing hands for 20 seconds minimal) is essential to combat this robust microorganism.2 , 53

-

7.

Training of the orthodontic team on disease symptoms, routes of transmission, infection control measures, and keeping up with regulation updates are beneficial during SARS-CoV-2 infection crisis.27 , 47 , 48 , 50

-

8.

Adequate ventilation of the operatory and waiting area with new air, high airflow, or with air filters is advised, with special attention to minimizing the number of patients in the waiting area and allowing adequate space for social distancing.6 , 50 , 54

-

9.

The operation room could be contaminated with droplets and aerosol. A recent study reported SARS-CoV-2 viability up to 3 hr in aerosol, with a half-life of 5.6 hr on stainless steel and 6.8 hr on plastic surfaces.55 Therefore, strict surface disinfection protocol should be applied after every patient.

-

10.

Medical wastes during the outbreak should be handled as infectious medical wastes. Double-layer yellow antileakage medical waste marked with a special tag is recommended.2 , 47 , 56 , 57

Fig 1.

Patient screening flowchart.

Orthodontic supplies and instruments

The following are recommendations to reduce the risk of cross-contamination and help protect vulnerable patients as well as the orthodontic staff.

-

1.

Orthodontic pliers can be sterilized with steam autoclave sterilization, ultrasound bath and thermal disinfection, or disinfected with chemical substances 2% glutaraldehyde or 0.25% peracetic acid. Instrument cassettes can be effectively used, with pliers preferably sterilized in an open position.58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63

-

2.

An autoclave is preferred over cold sterilization, without negatively affecting surface characterization of archwires.19 , 39 , 40 , 64 , 65

-

3.

Orthodontic markers can be autoclaved or disinfected using glutaraldehyde solution.43 , 66

-

4.

Cleaning photographic retractors with washer-disinfector were reported as the most effective method of decontamination.67

-

5.

Tungsten carbide debonding burs could be effectively decontaminated from bacterial infection.68

-

6.

It is safe to use tried-in orthodontic bands after adequate precleaning and sterilization.41 , 69 , 70

-

7.

Decontamination does not jeopardize clinical stability of miniscrews nor mechanical properties of elastomeric chains.42 , 71

-

8.

Flushing dental unit waterline for at least 2 min or using disinfectants improves the quality of water within the dental unit and minimize the risk of infection.72 , 73

Conclusions

In summary, SARS-CoV-2 is the first highly contagious pandemic infection of this millennium. Although cross-contamination within any dental setting has not been reported, dentists in all disciplines, including orthodontists, need to be constantly aware of the emerging infectious threats and informed of updates in infection control guidelines. The findings of this review reinforce the importance of good work practices, including hygiene, infection control, and personal protection. Given the high transmissibility of COVID-19, controlling aerosol and human-to-human contact while limiting treatment to emergency patients only is advised during the outbreak. It is the responsibility of the orthodontic team to ensure safety and stop cross-contamination within the clinical facility. Finally, the impact of COVID-19 on the orthodontic practice, cost of illness, and whether clear aligners that require minimal appointments are superior to fixed orthodontics in the event of a future outbreak, are questions that remain to be answered.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Khawlah Turkistani for her contribution during the work. This study was not supported by any research grant.

Footnotes

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and none were reported.

References

- 1.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng X., Xu X., Li Y., Cheng L., Zhou X., Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:9. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorbalenya A.E., Baker S.C., Baric R.S., de Groot R.J., Drosten C., Gulyaeva A.A. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report-11. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200131-sitrep-11-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=de7c0f7_4 Available at:

- 5.Chan J.F.W., Yuan S., Kok K.H., To K.K.W., Chu H., Yang J. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge Z.Y., Yang L.M., Xia J.J., Fu X.H., Zhang Y.Z. Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 and special precautions in dentistry. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report-51. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10 Available at:

- 8.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report-70. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200330-sitrep-70-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=7e0fe3f8_4 Available at:

- 9.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report-65. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200325-sitrep-65-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=ce13061b_2 Available at:

- 10.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassan S.A., Sheikh F.N., Jamal S., Ezeh J.K., Akhtar A. Coronavirus (COVID-19): a review of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e7355. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J., Zhou M., Liu F. Reasons for healthcare workers becoming infected with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105:100–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu X., Zhang L., Du H., Zhang J., Li Y.Y., Qu J. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1663–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin Y.H., Cai L., Cheng Z.S., Cheng H., Deng T., Fan Y.P. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Mil Med Res. 2020;7:4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.COVID-19 open research dataset (CORD-19) https://pages.semanticscholar.org/coronavirus-research Available at:

- 18.Leggat P.A., Kedjarune U., Smith D.R. Occupational health problems in modern dentistry: a review. Ind Health. 2007;45:611–621. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oshagh M., Hematiyan M.R., Mohandes Y., Oshagh M.R., Pishbin L. Autoclaving and clinical recycling: effects on mechanical properties of orthodontic wires. Indian J Dent Res. 2012;23:638–642. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.107382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klevens R.M., Moorman A.C. Hepatitis C virus: an overview for dental health care providers. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1340–1347. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radcliffe R.A., Bixler D., Moorman A., Hogan V.A., Greenfield V.S., Gaviria D.M. Hepatitis B virus transmissions associated with a portable dental clinic, West Virginia, 2009. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1110–1118. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redd J.T., Baumbach J., Kohn W., Nainan O., Khristova M., Williams I. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis B virus associated with oral surgery. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1311–1314. doi: 10.1086/513435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Younai F.S. Health care-associated transmission of hepatitis B & C viruses in dental care (dentistry) Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2009.11.010. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldman R.E., Schiff E.R. Hepatitis in dental professionals. JAMA. 1975;232:1228–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Starnbach H., Biddle P. A pragmatic approach to asepsis in the orthodontic office. Angle Orthod. 1980;50:63–66. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1980)050<0063:APATAI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence A.J., Mordecai R.M. Health and safety at work in orthodontic practice—part II. Br J Orthod. 1994;21:216–220. doi: 10.1179/bjo.21.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meng L., Hua F., Bian Z. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res. 2020;99:481–487. doi: 10.1177/0022034520914246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.To K.K.W., Tsang O.T.Y., Yip C.C.Y., Chan K.H., Wu T.C., Chan J.M.C. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;149:1–3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu J., Han B., Wang J. COVID-19: gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1518–1519. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu H., Zhong L., Deng J., Peng J., Dan H., Zeng X. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:8. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Micik R.E., Miller R.L., Mazzarella M.A., Ryge G. Studies on dental aerobiology. I. Bacterial aerosols generated during dental procedures. J Dent Res. 1969;48:49–56. doi: 10.1177/00220345690480012401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holloman J.L., Mauriello S.M., Pimenta L., Arnold R.R. Comparison of suction device with saliva ejector for aerosol and spatter reduction during ultrasonic scaling. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnes J.B., Harrel S.K., Rivera-Hidalgo F. Blood contamination of the aerosols produced by in vivo use of ultrasonic scalers. J Periodontol. 1998;69:434–438. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rautemaa R., Nordberg A., Wuolijoki-Saaristo K., Meurman J.H. Bacterial aerosols in dental practice - a potential hospital infection problem? J Hosp Infect. 2006;64:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bentley C.D., Burkhart N.W., Crawford J.J. Evaluating spatter and aerosol contamination during dental procedures. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;125:579–584. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1994.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huntley D.E., Campbell J. Bacterial contamination of scrub jackets during dental hygiene procedures. J Dent Hyg. 1998;72:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ricci M.L., Fontana S., Pinci F., Fiumana E., Pedna M.F., Farolfi P. Pneumonia associated with a dental unit waterline. Lancet. 2012;379:684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrel S.K., Molinari J. Aerosols and splatter in dentistry: a brief review of the literature and infection control implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:429–437. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crotty O.P., Davies E.H., Jones S.P. The effects of cross-infection control procedures on the tensile and flextural properties of superelastic nickel-titanium wires. Br J Orthod. 1996;23:37–41. doi: 10.1179/bjo.23.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pernier C., Grosgogeat B., Ponsonnet L., Benay G., Lissac M. Influence of autoclave sterilization on the surface parameters and mechanical properties of six orthodontic wires. Eur J Orthod. 2005;27:72–81. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjh076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irfan S., Irfan S., Fida M., Ahmad I. Contamination assessment of orthodontic bands after different pre-cleaning methods at a tertiary care hospital. J Orthod. 2019;46:220–224. doi: 10.1177/1465312519855402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pithon M.M., Ferraz C.S., Rosa F.C.S., Rosa L.P. Sterilizing elastomeric chains without losing mechanical properties. Is it possible? Dental Press J Orthod. 2015;20:96–100. doi: 10.1590/2176-9451.20.3.096-100.oar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Omidkhoda M., Rashed R., Bagheri Z., Ghazvini K., Shafaee H. Comparison of three different sterilization and disinfection methods on orthodontic markers. J Orthod Sci. 2016;5:14–17. doi: 10.4103/2278-0203.176653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coley-Smith A., Rock W.P. Bracket recycling–who does what? Br J Orthod. 1997;24:172–174. doi: 10.1093/ortho/24.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machen D.E. Orthodontic bracket recycling. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993;104:618–619. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(05)80447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo H., Zhou Y., Liu X., Tan J. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the utilization of emergency dental services. J Dent Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2020.02.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Z.Y., Meng L.Y. The prevention and control of a new coronavirus infection in department of stomatology [in Chinese] Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;55:E001. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1002-0098.2020.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang W., Jiang X. Measures and suggestions for the prevention and control of the novel coronavirus in dental institutions. Front Oral Maxillofac Med. 2020;2:4. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marui V.C., Souto M.L.S., Rovai E.S., Romito G.A., Chambrone L., Pannuti C.M. Efficacy of preprocedural mouthrinses in the reduction of microorganisms in aerosol: a systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150:1015–10126.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2019.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang H.S., Yao Z.Q., Wang W.M. Emergency management of prevention and control of the novel coronavirus infection in departments of stomatology. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;55:246–248. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112144-20200205-00037. [in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu C.W., Liu X.F., Jia Z.F. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. Lancet. 2020;395:e39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30313-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang D., Xu H., Rebaza A., Sharma L., Cruz C.S.D. Protecting health-care workers from subclinical coronavirus infection. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e13. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30066-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.World Health Organization WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44102/9789241597906_eng.pdf;jsessionid=00A9D7ACABAD2EE63D8BB679B4BD7885?sequence=1 Available at:

- 54.Dutil S., Meriaux A., de Latremoille M.C., Lazure L., Barbeau J., Duchaine C. Measurement of airborne bacteria and endotoxin generated during dental cleaning. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2009;6:121–130. doi: 10.1080/15459620802633957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shah R., Collins J.M., Hodge T.M., Laing E.R. A national study of cross infection control: ‘are we clean enough? Br Dent J. 2009;207:267–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization Safe management of wastes from health-care activities: a summary. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259491/WHO-FWC-WSH-17.05-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Available at:

- 58.Carvalho M.R., dos Santos da Silva M.A., de Sousa Brito C.A., Campelo V., Kuga M.C., Tonetto M.R. Comparison of antimicrobial activity between chemical disinfectants on contaminated orthodontic pliers. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2015;16:619–623. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Papaioannou A. A review of sterilization, packaging and storage considerations for orthodontic pliers. Int J Orthod Milwaukee. 2013;24:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vendrell R.J., Hayden C.L., Taloumis L.J. Effect of steam versus dry-heat sterilization on the wear of orthodontic ligature-cutting pliers. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;121:467–471. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.122175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hohlt W.F., Miller C.H., Neeb J.M., Sheldrake M.A. Sterilization of orthodontic instruments and bands in cassettes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990;98:411–416. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(05)81649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lall R., Sahu A., Jaiswal A., Kite S., Sowmya A.R., Sainath M.C. Evaluation of various sterilization processes of orthodontic instruments using biological indicators and conventional swab test method: a comparative study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19:698–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wichelhaus A., Bader F., Sander F.G., Krieger D., Mertens T. Effective disinfection of orthodontic pliers. J Orofac Orthop. 2006;67:316–336. doi: 10.1007/s00056-006-0622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mousavi S.M., Hormozi E., Moradi M., Shamohammadi M., Rakhshan V. Effects of autoclaving versus cold chemical (glutaraldehyde) sterilization on load-deflection characteristics of aesthetic coated archwires. Int Orthod. 2018;16:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ortho.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brindha M., Kumaran N.K., Rajasigamani K. Evaluation of tensile strength and surface topography of orthodontic wires after infection control procedures: an in vitro study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6(Suppl 1):S44–S48. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.137386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ascencio F., Langkamp H.H., Agarwal S., Petrone J.A., Piesco N.P. Orthodontic marking pencils: a potential source of cross-contamination. J Clin Orthod. 1998;32:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Benson P.E., Ebhohimen A., Douglas I. The cleaning of photographic retractors; a survey, clinical and laboratory study. Br Dent J. 2010;208:E14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.310. discussion 306-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sheriteh Z., Hassan T., Sherriff M., Cobourne M., Riley P. Decontamination of viable Streptococcus mutans from orthodontic tungsten carbide debonding burs. An in vitro microbiological study. J Orthod. 2010;37:181–187. doi: 10.1179/14653121043083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rerhrhaye W., Ouaki B., Zaoui F., Aalloula E. The effect of autoclave sterilization on the surface properties of orthodontic brackets after fitting in the mouth. Odontostomatol Trop. 2011;34:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fulford M.R., Ireland A.J., Main B.G. Decontamination of tried - in orthodontic molar bands. Eur J Orthod. 2003;25:621–622. doi: 10.1093/ejo/25.6.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akyalcin S., McIver H.P., English J.D., Ontiveros J.C., Gallerano R.L. Effects of repeated sterilization cycles on primary stability of orthodontic mini-screws. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:674–679. doi: 10.2319/082612-685.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chate R.A. An audit improves the quality of water within the dental unit water lines of general dental practices across the East of England. Br Dent J. 2010;209:E11. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chate R.A. An audit improves the quality of water within the dental unit water lines of three separate facilities of a United Kingdom NHS trust. Br Dent J. 2006;201:565–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4814206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]