Take Home Message

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the world. Urology needs to overcome these challenges. Our duty is to provide care under any circumstances and our privilege is to re-examine and advance our field. The use of novel communication and health technologies will ensure safety while maintaining high-quality care.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The global spread of the virus has overwhelmed health systems and caused widespread social and economic disruption [1]. Most countries have reacted by putting their society and the economy on hold to limit the ability of the virus to spread [2]. Urology specifically has shifted to emergency mode, with many elective procedures cancelled.

Until a vaccine or a cure for COVID-19 is developed, we have to adjust to be able to maintain a steady state of low-level transmission [3]. This will undoubtedly affect the medical world and urological practice dramatically. This document sets a platform for discussing the adaptations required. We acknowledge that health systems differ between countries, but here we try to highlight common themes.

General concerns ubiquitous to all medical practice:

-

•

Patient and staff safety and a sense of security;

-

•

Disruption of the continuity of care; and

-

•

Prioritization of delays.

Urology-specific concerns:

-

•

Most urological patients are older than 65 yr. This age group is particularly affected by COVID-19 [4].

-

•

Many invasive procedures performed are performed on an outpatient basis (cystoscopy, urodynamics, prostate biopsies, intravesical treatment).

-

•

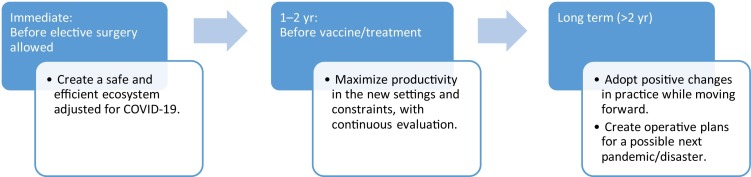

Most surgeries are elective and can be delayed for several months, but patients may suffer if these are delayed for a long period (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Timeline of goals for the immediate and long-term future.

2. Outpatient clinics

Urological outpatient clinics will have to adapt to new social distancing regulations that may differ between countries. The common theme will be to minimize unnecessary interactions while maintaining high-quality treatment by integrating novel technologies such as telemedicine. Telemedicine was developed to allow health care professionals to treat patients in remote locations. Now it will have widespread use.

-

(a)Immediate

-

iEnhancing a sense of security: It is essential that patients and staff feel safe. To this end, each clinic will need multiple hand sanitation booths, weekly staff testing for SARS-CoV-2, and identifiable signs (eg, SARS-CoV-2–negative tested).

-

iiMinimizing patient waiting times for physicians: Most centers now have electronic data and measurements for waiting times. We suggest personalization of physician–patient time interactions on the basis of behavioral analyses.

-

iiiTelemedicine: While the initial diagnosis needs to be in-person with protective measures, most follow-up visits could be performed via telemedicine. Medical insurers will need to consider reimbursement fees for this approach.

-

ivPersonal protective equipment (PPE): Each facility will have to decide which invasive procedures require PPE and what kind of PPE to use.

-

vAs there is some evidence that SARS-CoV-2 may also be transmitted via the feco-oral route [5], we suggest performing prostate biopsies and urodynamics on a day surgery basis.

-

i

-

(b)Intermediate term (1–2 yr)

-

iIntegration of patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) with telemedicine: Telemedicine creates distance between the patient and physician. In urology, many issues are very intimate and it is vital to establish adequate doctor-patient rapport.

-

iiTelemedicine communication skills: As telemedicine is a new tool we will have to master communication via video.

-

iiiIntegrated practice units (IPUs): The world of medicine is moving towards value-based medicine. What this essentially means is shifting the focus from the volume and profitability of services provided—physician visits, hospitalizations, and procedures—to the patient outcomes achieved [6]. As a field, we should seize the opportunities provided by telecommunication and technology to transform our approach.At the core of value transformation is changing the way we are organized. In urology, this requires a shift from the current organization by service to organization around the patient’s medical condition. This structure is termed an IPU. In an IPU, a dedicated team made up of clinical and nonclinical personnel provides the full care cycle for the patient’s condition. Many institutes already have multidisciplinary uro-oncology clinics, so moving to IPUs would be an easy transition.

-

i

-

(c)Long term (>2 yr)

-

iCreating a physical barrier between the main hospital and clinics: We may have a second or third wave of infection and we need to think of how to move outpatient clinics away from the main hospital.

-

iiConnected clinics: The COVID-19 pandemic will enhance the development of novel tools for monitoring patients at home. These will use technology to inform personalized medicine and care (eg, daily home urine tests to change nutrition for stone formers).

-

i

3. Operating rooms

There are several specific concerns regarding the operating room. First is the safety of staff and patients. There are case reports of severe complication for COVID-19 patients undergoing surgery [7]. However, some COVID-19–positive patients will need emergency surgery. Second, most countries have stopped elective surgeries completely and therefore many urological procedures have been delayed.

-

(a)Immediate

-

iTelemedicine preoperative clinics;

-

iiSARS-CoV-2 test for each elective patient 24 h before surgery;

-

iiiIsolated operating rooms for SARS-CoV-2–positive patients;

-

ivPrioritization of delayed surgeries; and

-

vIntegration of most short-stay surgeries into the outpatient day surgery schedule.

-

i

-

(b)Intermediate term (1–2 yr)

-

iIntegration of novel technology for preoperative teleclinics (eg, use camera to assess intubation ease, use 4-m walk test to determine surgical risk).

-

i

-

(c)Long term (>2 yr)

-

iOperative plans are needed to make sure that elective surgery continues if a second or third wave of COVID-19 occurs. Most surgical teams are not needed for providing COVID-19 care and are unemployed.

-

i

4. Department level

The main concern at department level is avoiding infectious spread. This could include staff-to-staff, staff-to-patient, patient-to-staff, and patient-to-patient transmission. To this end, departments will have to work in small integrated teams with minimal contact between teams. The challenge will be to maintain the departmental structure and medical education despite these restrictions.

-

(a)Immediate

-

iTransfer short-stay surgeries to day procedures outside the department;

-

iiEstablish an intermediate unit for long-stay surgeries (eg, cystectomy);

-

iiiEstablish a separate place for emergency admissions;

-

ivPrevent patient-to-staff transmission;

-

vDivide medical staff into teams with no overlap contact between them to avoid staff-to-staff and patient-to-staff transmission;

-

viInitiate staff meetings via videoconferencing;

-

viiAddress medical education and residency: ensure that residents teams include senior, intermediate, and new residents and that videoconference teaching is in place; and

-

viiiEstablish a framework for teams in the era of social distancing: patient care requires an integrated team of physicians, nurses, paramedics, and administrators who need to be able to maintain their teamwork from a distance.

-

i

5. Research

It is vital that even in these unprecedented times we should focus not only on current events but also on what actions we can take in the future.

-

i

Establish a database of delayed treatments and surgeries to understand the possible effects on outcome;

-

ii

Establish an international database of surgical patients with COVID-19 before surgery or during recovery; and

-

iii

Establish prospective databases to be able to evaluate compliance, satisfaction, and outcomes for the new pathways developed for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up for our patients (ie, telemedicine).

6. Summary

In summary, we are in the midst of a worldwide pandemic with catastrophic consequences. We need to adjust the way we think regarding how we carry out even very simple tasks. However, as doctors we need to make sure that our patients will be able to have access to safe medicine. We should also seize this opportunity to advance our field moving forward.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/.

- 2.Wilder-Smith A., Freedman D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020;27 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa020. taaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Strategic preparedness and response plan. www.who.int/publications-detail/strategic-preparedness-and-response-plan-for-the-new-coronavirus/.

- 4.Murthy S., Gomersall C.D., Fowler R.A. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1499–1500. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hindson J. COVID- 19: faecal–oral transmission? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:259. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0295-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Harten W.H. Turning teams and pathways into integrated practice units: appearance characteristics and added value. Int J Care Coord. 2018;21:113–116. doi: 10.1177/2053434518816529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lei S., Jiang F., Su W. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;5:100331. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]