Editor—We read with interest the correspondence by Cubillos and colleagues1 and Yong and Chen.2 Cubillos and colleagues1 describe the design and manufacture of a ‘negative-pressure airflow isolation chamber’ to reduce the risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission during airway management, and Yong and Chen2 report the use of flexible plastic screens and tents for the same purpose. A number of similar reports have been published in recent literature describing the use of various ‘intubation boxes’ and drapes,3, 4, 5 all of which aim to provide a physical barrier to aerosols and droplets. Although these innovations are doubtless well-meaning, we are concerned that any additional protection that such devices may afford is gained at the cost of increased difficulty in managing the airway.

The concept of difficult airway in the critically ill comprises anatomical, physiological, and environmental elements,6 exacerbated in the current pandemic by human factors and the communication limitations imposed by highly restrictive personal protective equipment.7 , 8 In our own anecdotal experience, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) appears to be associated with laryngeal oedema independent of that associated with prolonged tracheal intubation,9 making airway management potentially more challenging.

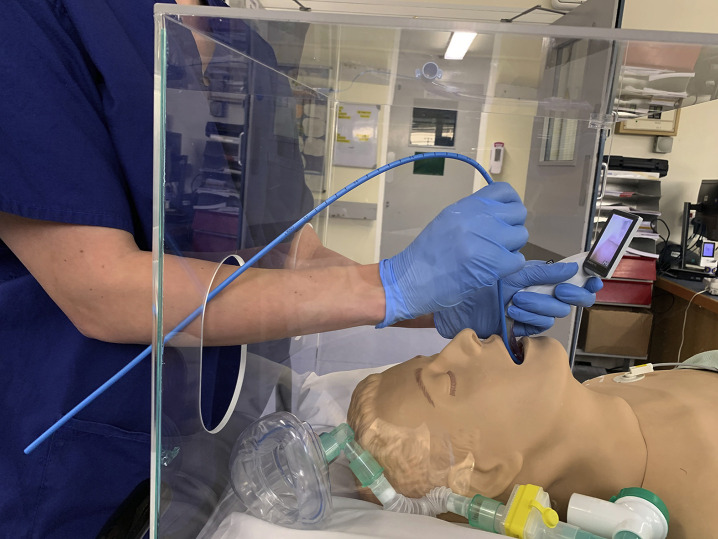

We trialled the use of a rigid intubation box similar to that proposed by Canelli and colleagues3 in a simulation setting, and found that the presence of a physical barrier increased the difficulty of tracheal intubation, especially during transition between airway devices and when using intubation adjuncts, such as the gum-elastic bougie (Fig. 1 ). A physical limitation in dexterity when using intubation boxes was predicted by Cubillos and colleagues1 in their letter, and our experiences support this prediction. However, we are concerned that similar problems may be encountered with all barrier devices. We advise caution in adopting the use of any physical enclosure in practice, as existing airway devices were not designed to be used in conjunction with intubation boxes, and airway management training has hitherto not included their use. There is also the question of how and when to remove barrier enclosures that lack any mechanism for air extraction or exchange without dispersion of high concentrations of aerosolised SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Fig. 1.

Use of a gum-elastic bougie and McGrath videolaryngoscope (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) with an intubation box for simulated intubation.

Managing difficult airways in the critically ill is challenging,6 and we believe this may be compounded by such home-made aids, however well intentioned. We must protect our staff during high-risk procedures, but not when this confers a threat to patient safety. Whilst both the safety and efficacy of barrier enclosures in airway management remain unproved, our focus should continue to be on the use of appropriate and well-fitted personal protective equipment, worn and disposed of effectively.

Declarations of interest

CS is a former member of the editorial board of BJA Education. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cubillos J., Querney J., Rankin A., Moore J., Armstrong K. A multipurpose portable negative air flow isolation chamber for aerosol generating medical procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Anaesth. 2020;27 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.007. Advance Access published on April. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yong P.S.A., Chen X. Reducing droplet spread during airway manipulation: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. Br J Anaesth. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.007. Advance Access published on April 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canelli R., Connor C.W., Gonzalez M., Nozari A., Ortega R. Barrier enclosure during endotracheal intubation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1957–1958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moraga F.A..L., Moraga E.L., Moraga F.L. Aerosol box, an operating room security measure in COVID-19. World J Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05542-x. Advance Access published on April 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown S., Patrao F., Verma S., Lean A., Flack S., Polaner D. Barrier system for airway management for COVID-19 patients. Anesth Analg. 2020 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004876. Advance Access published on April 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgs A., McGrath B.A., Goddard C. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:323–352. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgs A., Cook T.M., McGrath B.A. Airway management in the critically ill: the same, but different. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117 doi: 10.1093/bja/aew055. i5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook T.M., El-Boghdadly K., McGuire B., McNarry A.F., Patel A., Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:785–799. doi: 10.1111/anae.15054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGrath B.A., Wallace S., Goswamy J. Laryngeal oedema associated with COVID-19 complicating airway management. Anaesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1111/anae.15092. Advance Access published on April 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]