Key Points

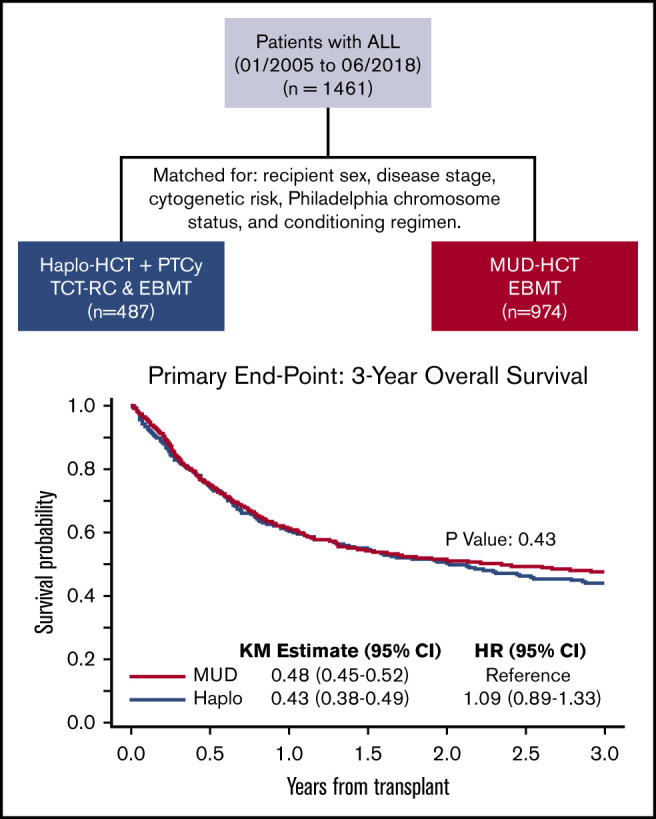

HCT outcomes were retrospectively compared between patients with ALL who underwent haploidentical (n = 487) or MUD (n = 974) transplant.

HaploHCT with PTCy patients and those undergoing MUD HCT with conventional GVHD prophylaxis (plus or minus ATG) had comparable outcomes.

Abstract

We compared outcomes of 1461 adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) receiving hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from a haploidentical (n = 487) or matched unrelated donor (MUD; n = 974) between January 2005 and June 2018. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis was posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy), calcineurin inhibitor (CNI), and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) for haploidentical, and CNI with MMF or methotrexate with/without antithymoglobulin for MUDs. Haploidentical recipients were matched (1:2 ratio) with MUD controls for sex, conditioning intensity, disease stage, Philadelphia-chromosome status, and cytogenetic risk. In the myeloablative setting, day +28 neutrophil recovery was similar between haploidentical (87%) and MUD (88%) (P = .11). Corresponding rates after reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) were 84% and 88% (P = .47). The 3-month incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD (aGVHD) and 3-year chronic GVHD (cGVHD) was similar after haploidentical compared with MUD: myeloablative conditioning, 33% vs 34% (P = .46) for aGVHD and 29% vs 31% for cGVHD (P = .58); RIC, 31% vs 30% (P = .06) for aGVHD and 24% vs 29% for cGVHD (P = .86). Among patients receiving myeloablative regimens, 3-year probabilities of overall survival were 44% and 51% with haploidentical and MUD (P = .56). Corresponding rates after RIC were 43% and 42% (P = .6). In this large multicenter case-matched retrospective analysis, despite the limitations of a registry-based study (ie, unavailability of key elements such as minimal residual disease testing), our analysis indicated that outcomes of patients with ALL undergoing HCT from a haploidentical donor were comparable with 8 of 8 MUD transplantations.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT; alloHCT) is the treatment of choice for most adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).1-5 Unfortunately, donor availability remains as one of the major challenges for transplant success in this patient population. Although HLA matched sibling donors are the preferred donors for alloHCT, such donors are available for <30% of patients. For patients with no matched sibling donor, transplant from a matched unrelated donor (MUD) has similar transplant outcomes.6 Although the likelihood of finding an 8 of 8 MUD for the white population is ∼70%, this probability falls to <20% for African Americans and other ethnic minorities,7 and becomes even more challenging for mixed-race individuals.8 Unfortunately, an average of 3 to 4 months is required to identify a MUD and procure hematopoietic progenitor cells.9

Over the last decade, haploidentical donors have evolved as an alternative source of donor cells. More than 95% of patients have at least 1 HLA-haploidentical first-degree donor with an average number of haploidentical donors available per patient of 2.7.10,11 Historically, the success of T-cell–replete haploidentical HCT (HaploHCT) was limited by high rates of graft rejection, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and nonrelapse mortality (NRM).12 In recent years, administration of high-dose posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy), a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI; ie, tacrolimus, cyclosporine), in combination with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) for GVHD prophylaxis after HaploHCT, has shown lower rates of NRM without significantly compromising engraftment, and comparable rates of GVHD to transplantation from a matched donor.13,14 Using this strategy, the risk of fatal infections was also lower, due to the more effective immune reconstitution, presumably related to retaining more memory T cells in the graft.15

Several single-center and registry-based studies have compared T-cell–replete HaploHCT with matched donor transplants in acute myeloid leukemia and lymphomas, and reported similar outcomes between these donor sources.16-22 More recently, 2 retrospective studies have described favorable outcomes of patients with ALL undergoing HaploHCT with PTCy23,24; a recent retrospective study by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) indicated that outcomes of adult patients with ALL who underwent HaploHCT with or without antithymoglobulin (ATG; n = 136) in their first remission are comparable to MUD (n = 809) or mismatched unrelated donor (n = 289) transplants.25 The current study is a matched-pair analysis with detailed comparison of transplant outcomes in ALL patients who underwent HaploHCT with PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis and MUD transplant.

Patients and methods

Data retrieval and inclusion criteria

For patients who underwent MUD HCT (n = 2871), data were provided from the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the EBMT group registry. The EBMT registry is the largest database of HCT patients in Europe, with >600 transplant centers reporting all consecutive HCTs and follow-up data once a year. For patients who underwent HaploHCT, data were obtained from the Haploidentical Transplant and Cellular Therapy–Research Consortium (TCT-RC) (n = 181) and the ALWP of the EBMT (n = 382). The TCT-RC is a voluntary working group of 6 transplant centers. Participating centers to this analysis include City of Hope National Medical Center (Duarte, CA; n = 25), MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX; n = 43), Northside Hospital (Atlanta, GA; n = 48), Instituto de Cancerologia–Clinica Las Americas (Medellin, Colombia; n = 23), Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, FL; n = 17), and Washington University in St. Louis (St. Louis, MO; n = 13).

Adult patients with ALL over 18 years of age who received their first alloHCT between January 2005 and June 2018 were included. Recipients of HaploHCT (mismatched at least 2 or more HLA loci to donors) received predominantly bone marrow (BM) or unmanipulated peripheral blood (PB) stem cells (PBSCs) or as the graft source. GVHD prophylaxis for HaploHCT patients consisted of PTCy (50 mg/kg for 2 days), a CNI, and MMF. Recipients of MUD HCT (8 of 8 matched at the allele level at HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DRB1) received unmanipulated graft (PBSC or BM) and GVHD prophylaxis consisting of a CNI and minimethotrexate or MMF. ATG was added in 64% of MUD HCTs. Patients received either myeloablative conditioning (MAC) or reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens according to previously accepted criteria.26 Patients with unknown sex or conditioning intensity (n = 36), HaploHCT recipients who received ATG as GVHD prophylaxis (n = 30), or patients who were alive but were followed for <100 days (n = 176) were excluded. The institutional review boards of all participating centers approved this study.

End points

Overall survival (OS) was defined as time from transplant to death from any cause. Surviving patients were censored at the last contact. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as time from transplant to disease relapse or death of any cause, whichever came first. RFS was censored at last contact if patients remained alive and disease-free. GVHD-free RFS events were defined as the earliest occurrence of grade III-IV acute GVHD, extensive chronic GVHD, disease relapse, or death from any cause since transplant. Neutrophil recovery was defined as achieving an absolute neutrophil count of ≥0.5 × 109/L for 3 consecutive days. Acute and chronic GVHD were graded using standard criteria.27,28 NRM was defined as time from transplant to death in continuous complete remission. Relapse was defined as time from transplant to morphologic, cytogenetic, or molecular leukemia recurrence. NRM and relapse were competing risk events to each other.

Statistical analysis

Eligible patients with ALL who underwent HaploHCT at 6 TCT-RC centers and the ALWP of the EBMT (n = 512) were matched at a 1:2 ratio with MUD recipients from the EBMT database (n = 2680), based on recipient sex, cytogenetic risk, Philadelphia-chromosome status, disease stage, and conditioning intensity. MUD recipients were randomly selected if their ratio of MUD to Haplo was >2:1 in matching strata. HaploHCT patients who had <2 matched MUD controls were excluded from the analyses (n = 25). Differences in other baseline patient, donor, and disease characteristics by donor type were compared using χ2 tests or Wilcoxon tests whenever appropriate. Multivariable Cox regression models were constructed to examine the differences in OS or RFS by donor type when adjusting for the covariates, and classified by matching strata. Multivariable Fine and Gray models were used to assess the differences in NRM, relapse, neutrophil engraftment, and acute or chronic GVHD by donor type when controlling for covariates, and were classified by matching strata. Backward stepwise selection at the 0.1 level was used to include covariates in each final multivariable model. The following covariates were considered: age (<30 years, 30-39 years, 40-54 years, and ≥55 years), Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), disease type, months from diagnosis to transplant (≤6 months, >6-12 months, and >12 months), female donor to male recipient, donor/recipient cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus, graft source, and transplant era. Total-body irradiation–based MAC was also considered in the models among patients who received this conditioning regimen. The robust sandwich estimates29 were used to take intracenter correlation (center-effect correlations) into account for the Cox and Fine and Gray regression models. Differences in clinical outcomes by donor type were examined in all patients overall, and by conditioning intensity, separately. The assumption of proportionality was examined using plots of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals or the cumulative sums of residuals and corresponding tests.30,31

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Two-sided P values were reported. A significance level of .05 was used for all tests.

Results

Patient, disease, and transplant characteristics

Table 1 shows patient, disease, and transplant characteristics. Matches were sought for the main variables known to impact outcome of transplant (ie, cytogenetic risk, Philadelphia-chromosome status, disease stage prior to HCT, sex, and conditioning intensity). Compared with MUD, HaploHCT recipients were younger in age (median age at HCT of 33 years vs 36 years; P = .02), received transplant at a later time after diagnosis (time from diagnosis to transplant >12 months in 42% vs 36%; P = .02), received stem cells from an older donor (median donor age of 38 years vs 32 years; P < .0001) or a female donor (female donor to male recipient in 27% vs 13%; P < .0001), and were more likely to receive BM as the graft source (49% vs 17%; P < .0001).

Table 1.

Patient, disease, and transplant characteristics

| Total* (N = 1461) | Haplo* (n = 487) | MUD* (n = 974) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant, y | .018 | |||

| Median (range) | 35 (18-76) | 33 (18-73) | 36 (18-76) | |

| Interquartile range | 25, 49 | 24, 46 | 25, 50 | |

| <30 | 579 (40) | 208 (43) | 371 (38) | .12 |

| 30-39 | 281 (19) | 98 (20) | 183 (19) | |

| 40-54 | 350 (24) | 111 (23) | 239 (25) | |

| ≥55 | 251 (17) | 70 (14) | 181 (19) | |

| Recipient sex | 1.0 | |||

| Male | 909 (62) | 303 (62) | 606 (62) | |

| Female | 552 (38) | 184 (38) | 368 (38) | |

| KPS | .0001 | |||

| 90-100 | 978 (67) | 321 (66) | 657 (67) | |

| ≤80 | 388 (27) | 151 (31) | 237 (24) | |

| NA | 95 (7) | 15 (3) | 80 (8) | |

| Cytogenetic risk | 1.0 | |||

| Poor risk | 489 (33) | 163 (33) | 326 (33) | |

| Not poor | 972 (67) | 324 (67) | 648 (67) | |

| Philadelphia-chromosome status | 1.0 | |||

| Ph+ | 351 (24) | 117 (24) | 234 (24) | |

| Ph− | 1110 (76) | 370 (76) | 740 (76) | |

| Disease stage prior to HCT | 1.0 | |||

| CR1 | 768 (53) | 256 (53) | 512 (53) | |

| CR2+ | 468 (32) | 156 (32) | 312 (32) | |

| Active disease | 225 (15) | 75 (15) | 150 (15) | |

| ALL type | .66 | |||

| B-ALL | 1044 (71) | 345 (71) | 699 (72) | |

| T-ALL | 322 (22) | 113 (23) | 209 (21) | |

| Other | 95 (7) | 29 (6) | 66 (7) | |

| From diagnosis to transplant, mo | .024 | |||

| ≤6 | 398 (27) | 114 (23) | 284 (29) | |

| >6-12 | 510 (35) | 168 (34) | 342 (35) | |

| >12 | 553 (38) | 205 (42) | 348 (36) | |

| HCT Comorbidity Index | <.0001 | |||

| 0 | 147 (10) | 98 (20) | 49 (5) | |

| 1-2 | 92 (6) | 71 (15) | 21 (2) | |

| >2 | 94 (6) | 82 (17) | 12 (1) | |

| NA | 1128 (77) | 236 (48) | 892 (92) | |

| Donor age, y † | <.0001 | |||

| Median (range) | 34 (13-76) | 38 (13-76) | 32 (18-62) | |

| Interquartile range | 26, 45 | 26, 49 | 26, 40 | |

| <30 | 342 (23) | 146 (30) | 196 (20) | <.0001 |

| 30-50 | 443 (30) | 200 (41) | 243 (25) | |

| ≥50 | 127 (9) | 104 (21) | 23 (2) | |

| NA | 549 (38) | 37 (8) | 512 (53) | |

| Donor sex | <.0001 | |||

| Male | 966 (66) | 276 (57) | 690 (71) | |

| Female | 468 (32) | 211 (43) | 257 (26) | |

| NA | 27 (2) | 27 (3) | ||

| Female donor to male recipient | <.0001 | |||

| Yes | 262 (18) | 131 (27) | 131 (13) | |

| No | 1172 (80) | 356 (73) | 816 (84) | |

| NA | 27 (2) | 27 (3) | ||

| Donor/Recipient CMV serostatus | <.0001 | |||

| D−/R− | 318 (22) | 43 (9) | 275 (28) | |

| D−/R+ | 366 (25) | 84 (17) | 282 (29) | |

| D+/R− | 130 (9) | 41 (8) | 89 (9) | |

| D+/R+ | 581 (40) | 303 (62) | 278 (29) | |

| Unknown | 66 (5) | 16 (3) | 50 (5) | |

| Conditioning intensity | 1.0 | |||

| Myeloablative | 1074 (74) | 358 (74) | 716 (74) | |

| Reduced | 387 (26) | 129 (26) | 258 (26) | |

| Stem cell source | <.0001 | |||

| BM | 405 (28) | 237 (49) | 168 (17) | |

| PBMC | 1056 (72) | 250 (51) | 806 (83) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | ||||

| Sirolimus-based | 23 (2) | 23 (2) | ||

| MTX-based | 664 (45) | 664 (68) | ||

| CellCept-based | 287 (20) | 287 (29) | ||

| PTCy/CellCept/CNI | 487 (33) | 487 (100) | ||

| ATG added | 626 (43) | 0 (0) | 626 (64) | |

| Transplant period | <.0001 | |||

| 2005-2012 | 695 (48) | 86 (18) | 609 (63) | |

| 2013-2018 | 766 (52) | 401 (82) | 365 (37) |

B-ALL, B-cell ALL; CR1, first complete remission; CR2, second complete remission; D, donor; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not applicable; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; R, recipient; T-ALL, T-cell ALL.

Values expressed as n (%), unless otherwise specified in a row heading.

For the “Donor age” section only: Total, N = 912; Haplo, n = 450; MUD, n = 462.

GVHD prophylaxis in HaploHCT patients consisted of PTCy, a CNI, and MMF (100%), and MUD patients received a CNI in 98% (or sirolimus 2%) with methotrexate (68%) and/or MMF (29%). The majority of HaploHCT recipients received transplants after 2013 (82%), reflecting the recent trend in use of PTCy as a GVHD prophylaxis for this group of patients.

To investigate the impact of conditioning regimen intensity on transplant outcomes, we divided patients into 2 subpopulations of MAC or RIC (supplemental Table 1A). The detailed conditioning regimen is summarized in supplemental Table 1B. Within the MAC group, total-body irradiation–based conditioning was used in 49% in the haploidentical and 75% in the MUD transplant recipients (P < .0001).

Hematopoietic recovery

Neutrophil recovery rates at day 28 post-HCT were not statistically different between Haplo (86%) and MUD (88%), (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.95-1.24; P = .24) (supplemental Table 2). In subgroup analysis, using a multivariable regression model, when BM was used as the graft source, a significantly faster neutrophil engraftment was observed in patients undergoing HaploHCT (HR = 1.27; 95% CI, 1.01-1.59; P = .038). Engraftment was not different in patients who underwent a transplant in first complete remission (CR1), or received MAC or RIC, and PBSCs as the graft source in Haplo vs MUD HCT (supplemental Table 3).

Survival outcomes

With a median follow-up of 3.0 years (range, 0.3-12.6 years), OS and RFS at 3 years posttransplant were not different between recipients of Haplo and MUD HCT (OS [HR = 1.09; 95% CI, 0.89-1.33; P = .43]; RFS [HR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.87-1.27; P = .60]) (Table 2). The 3-year probabilities of GVHD-free RFS for this cohort was 31% (95% CI, 26% to 37%) in HaploHCT as compared with 32% (95% CI, 29% to 36%) in MUD HCT recipients (HR = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.91-1.22; P = .47).

Table 2.

Survival outcomes

| n | OS | RFS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-y (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | P * | 3-y (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | P * | ||

| Donor type | |||||||

| MUD | 974 | 0.48 (0.45, 0.52) | Reference | .43 | 0.42 (0.39, 0.45) | Reference | .60 |

| Haplo | 487 | 0.43 (0.38, 0.49) | 1.09 (0.89, 1.33) | 0.39 (0.34, 0.44) | 1.05 (0.87, 1.27) | ||

| Recipient age, y | |||||||

| <30 | 579 | 0.53 (0.49, 0.57) | Reference | <.001 | 0.48 (0.43, 0.52) | Reference | <.001 |

| 30-39 | 281 | 0.47 (0.40, 0.53) | 1.29 (1.06, 1.57) | 0.40 (0.33, 0.46) | 1.32 (1.09, 1.60) | ||

| 40-54 | 350 | 0.46 (0.40, 0.51) | 1.34 (1.11, 1.61) | 0.42 (0.36, 0.47) | 1.29 (1.08, 1.54) | ||

| ≥55 | 251 | 0.34 (0.28, 0.41) | 1.92 (1.50, 2.45) | 0.27 (0.21, 0.33) | 1.83 (1.43, 2.34) | ||

| KPS † | |||||||

| 90-100 | 978 | 0.51 (0.47, 0.54) | Reference | <.001 | 0.44 (0.40, 0.47) | Reference | <.001 |

| ≤80 | 388 | 0.36 (0.31, 0.41) | 1.51 (1.28, 1.79) | 0.33 (0.28, 0.38) | 1.35 (1.15, 1.58) | ||

| ALL subtype | |||||||

| B-ALL | 1044 | 0.48 (0.44, 0.51) | Reference | .71 | 0.42 (0.39, 0.45) | Reference | .68 |

| T-ALL | 322 | 0.46 (0.40, 0.52) | 1.00 (0.82, 1.22) | 0.38 (0.33, 0.44) | 1.08 (0.90, 1.30) | ||

| Other | 95 | 0.41 (0.30, 0.52) | 1.12 (0.84, 1.50) | 0.38 (0.26, 0.49) | 1.00 (0.74, 1.35) | ||

| Months from diagnosis to HCT | |||||||

| ≤6 | 398 | 0.55 (0.50, 0.61) | Reference | .33 | 0.47 (0.41, 0.52) | Reference | .68 |

| >6-12 | 510 | 0.50 (0.45, 0.55) | 1.15 (0.95, 1.38) | 0.47 (0.43, 0.52) | 1.05 (0.88, 1.24) | ||

| >12 | 553 | 0.38 (0.33, 0.42) | 1.15 (0.92, 1.45) | 0.31 (0.27, 0.35) | 1.10 (0.89, 1.37) | ||

| HCT Comorbidity Index † | |||||||

| 0 | 147 | 0.57 (0.45, 0.67) | Reference | .14 | 0.43 (0.31, 0.55) | Reference | .30 |

| 1-2 | 92 | 0.28 (0.16, 0.43) | 1.52 (0.95, 2.42) | 0.29 (0.18, 0.42) | 1.34 (0.89, 2.02) | ||

| >2 | 94 | 0.42 (0.27, 0.57) | 0.95 (0.61, 1.49) | 0.39 (0.25, 0.53) | 0.95 (0.66, 1.36) | ||

| Donor age, y † | |||||||

| <30 | 342 | 0.44 (0.38, 0.50) | Reference | .62 | 0.39 (0.33, 0.45) | Reference | .45 |

| 30-49 | 443 | 0.47 (0.42, 0.52) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.17) | 0.42 (0.37, 0.47) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.15) | ||

| ≥50 | 127 | 0.45 (0.35, 0.55) | 1.11 (0.80, 1.55) | 0.41 (0.31, 0.50) | 1.12 (0.84, 1.50) | ||

| Female donor to male recipient † | |||||||

| No | 1172 | 0.47 (0.44, 0.50) | Reference | .86 | 0.41 (0.38, 0.44) | Reference | .54 |

| Yes | 262 | 0.47 (0.40, 0.54) | 0.98 (0.81, 1.19) | 0.39 (0.32, 0.45) | 1.06 (0.89, 1.25) | ||

| CMV serostatus † | |||||||

| D+/R+ | 581 | 0.46 (0.41, 0.50) | Reference | .41 | 0.39 (0.35, 0.44) | Reference | .63 |

| D+/R− | 130 | 0.49 (0.39, 0.57) | 0.96 (0.75, 1.23) | 0.46 (0.37, 0.54) | 0.94 (0.74, 1.21) | ||

| D−/R+ | 366 | 0.47 (0.41, 0.53) | 0.90 (0.73, 1.11) | 0.43 (0.37, 0.48) | 0.88 (0.73, 1.07) | ||

| D−/R− | 318 | 0.50 (0.44, 0.56) | 0.83 (0.67, 1.04) | 0.41 (0.35, 0.47) | 0.97 (0.80, 1.18) | ||

| Stem cell source | |||||||

| PB | 1056 | 0.48 (0.45, 0.51) | Reference | .082 | 0.42 (0.38, 0.45) | Reference | .074 |

| BM | 405 | 0.44 (0.38, 0.49) | 1.18 (0.98, 1.42) | 0.39 (0.34, 0.44) | 1.18 (0.98, 1.42) | ||

| Transplant period | |||||||

| 2005-2012 | 695 | 0.47 (0.43, 0.50) | Reference | .80 | 0.42 (0.38, 0.46) | Reference | .52 |

| 2013-2018 | 766 | 0.46 (0.42, 0.51) | 0.98 (0.83, 1.16) | 0.39 (0.35, 0.44) | 1.05 (0.90, 1.22) | ||

Based on the multivariable Cox regression model adjusted for recipient age, KPS, and stem cell source, and stratified by matching variables: sex, cytogenetic risk, Ph status, disease stage, and conditioning intensity. The robust sandwich covariance matrix estimate was used to adjust for within-center correlation.

Patients who had missing values were included in the model when the variable was covariates, but were excluded when the variable was predictor of interest.

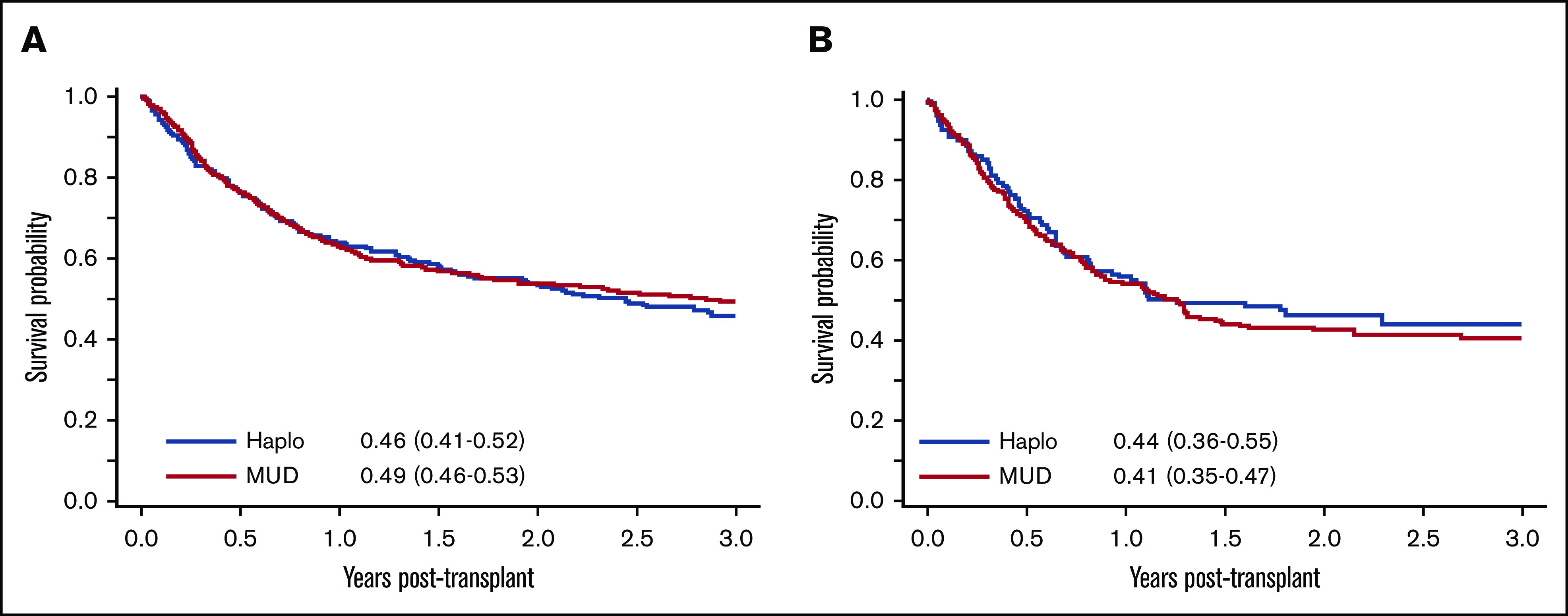

In multivariable analysis, when recipient age above 30 years was assigned as the reference, HRs of 1.29 (95% CI, 1.06-1.57), 1.34 (95% CI, 1.11-1.61), and 1.92 (95% CI, 1.50-2.45) were achieved for recipient ages at 30 to 39 years, 40 to 54 years, and ≥55 years, respectively (P < .001); KPS of ≤80% (HR = 1.51; 95% CI, 1.28-1.79; P < .001) was also found to be a predictor of lower 3-year OS and RFS (Table 2). Other variables tested using the regression model, including ALL subtype, time from diagnosis to transplant, donor age and sex, CMV status, and stem cell source, were not predictors of survival outcomes. In subgroup analysis, no differences were detected when survival outcomes were compared between recipients of Haplo and MUD HCT based on the intensity of conditioning regimen (Figure 1), remission status (CR1), graft source, and different disease groups of Ph+ ALL, Ph− ALL, and T-cell ALL (supplemental Table 3).

Figure 1.

Comparison of survival outcomes between patients undergoing Haplo and MUD HCT. (A) OS post-MAC. (B) OS post-RIC.

Approximately two-thirds of the MUD HCT recipients (64%) received ATG (Table 1). When we investigated the effect of ATG administration on survival outcomes, no statistical significance was detected. Compared with haploidentical transplants, mortality risks for non-ATG and ATG-containing regimens in MUD HCT recipients were similar (HR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.68-1.09; P =. 22).

Relapse and NRM

In multivariable analysis, after adjusting for potential confounders, age above 40 years predicted for higher rate of NRM at 3 years post-HCT (HR = 1.33 [95% CI, 1.01-1.76] and 1.73 [95% CI, 1.26-2.36] for 40-54 years and ≥55 years, respectively; P < .001). Moreover, KPS ≤80 also predicted for higher NRM (with HR = 1.50 [95% CI, 1.18-1.89]; P < .001). ALL subtype, months from diagnosis to HCT, female donor to male recipient, donor age, CMV status, and stem cell source did not affect either NRM or relapse (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relapse and NRM

| n | Relapse | NRM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-y (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)* | P * | 3-y (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)* | P * | ||

| Donor type | |||||||

| MUD | 974 | 0.34 (0.31, 0.37) | Reference | .68 | 0.24 (0.21, 0.27) | Reference | .19 |

| Haplo | 487 | 0.37 (0.32, 0.41) | 0.95 (0.75, 1.21) | 0.24 (0.20, 0.29) | 1.19 (0.92, 1.55) | ||

| Recipient age, y | |||||||

| <30 | 579 | 0.31 (0.27, 0.36) | Reference | .038 | 0.21 (0.18, 0.25) | Reference | .006 |

| 30-39 | 281 | 0.40 (0.34, 0.46) | 1.34 (1.05, 1.72) | 0.20 (0.16, 0.25) | 1.10 (0.80, 1.49) | ||

| 40-54 | 350 | 0.33 (0.27, 0.38) | 1.15 (0.90, 1.46) | 0.26 (0.21, 0.31) | 1.33 (1.01, 1.76) | ||

| ≥55 | 251 | 0.40 (0.34, 0.47) | 1.39 (1.07, 1.82) | 0.33 (0.27, 0.39) | 1.73 (1.26, 2.36) | ||

| KPS † | |||||||

| 90-100 | 978 | 0.35 (0.32, 0.38) | Reference | .76 | 0.21 (0.18, 0.24) | Reference | <.001 |

| ≤80 | 388 | 0.36 (0.31, 0.41) | 0.97 (0.79, 1.19) | 0.31 (0.26, 0.36) | 1.50 (1.18, 1.89) | ||

| ALL subtype | |||||||

| B-ALL | 1044 | 0.33 (0.30, 0.36) | Reference | .56 | 0.25 (0.22, 0.27) | Reference | .70 |

| T-ALL | 322 | 0.39 (0.33, 0.44) | 1.10 (0.89, 1.37) | 0.23 (0.18, 0.28) | 1.00 (0.75, 1.33) | ||

| Other | 95 | 0.40 (0.28, 0.51) | 1.15 (0.79, 1.65) | 0.22 (0.14, 0.32) | 0.83 (0.53, 1.30) | ||

| Months from diagnosis to HCT | |||||||

| ≤6 | 398 | 0.32 (0.27, 0.37) | Reference | .25 | 0.21 (0.17, 0.26) | Reference | .11 |

| >6-12 | 510 | 0.28 (0.24, 0.32) | 0.80 (0.62, 1.04) | 0.24 (0.21, 0.28) | 1.31 (0.99, 1.73) | ||

| >12 | 553 | 0.43 (0.39, 0.48) | 0.86 (0.65, 1.14) | 0.26 (0.22, 0.29) | 1.41 (0.98, 2.03) | ||

| HCT Comorbidity Index † | |||||||

| 0 | 147 | 0.34 (0.24, 0.44) | Reference | .89 | 0.23 (0.14, 0.32) | Reference | .39 |

| 1-2 | 92 | 0.43 (0.30, 0.55) | 1.09 (0.66, 1.78) | 0.28 (0.18, 0.38) | 1.36 (0.79, 2.34) | ||

| >2 | 94 | 0.36 (0.26, 0.47) | 0.96 (0.57, 1.61) | 0.24 (0.12, 0.39) | 0.95 (0.52, 1.74) | ||

| Donor age, y † | |||||||

| <30 | 342 | 0.37 (0.31, 0.43) | Reference | .99 | 0.24 (0.19, 0.29) | Reference | .50 |

| 30-49 | 443 | 0.37 (0.32, 0.42) | 0.99 (0.77, 1.27) | 0.21 (0.18, 0.26) | 0.94 (0.69, 1.27) | ||

| ≥50 | 127 | 0.33 (0.25, 0.42) | 0.99 (0.69, 1.41) | 0.26 (0.18, 0.34) | 1.19 (0.78, 1.81) | ||

| Female-to-male HCT † | |||||||

| No | 1172 | 0.34 (0.31, 0.37) | Reference | .087 | 0.24 (0.22, 0.27) | Reference | .70 |

| Yes | 262 | 0.39 (0.33, 0.46) | 1.22 (0.97, 1.53) | 0.22 (0.17, 0.27) | 0.94 (0.70, 1.27) | ||

| CMV serostatus † | |||||||

| D+/R+ | 581 | 0.37 (0.33, 0.41) | Reference | .062 | 0.24 (0.20, 0.28) | Reference | .14 |

| D+/R− | 130 | 0.30 (0.22, 0.38) | 0.89 (0.62, 1.28) | 0.24 (0.17, 0.32) | 1.11 (0.78, 1.58) | ||

| D−/R+ | 366 | 0.32 (0.27, 0.37) | 0.85 (0.67, 1.07) | 0.25 (0.20, 0.30) | 1.04 (0.79, 1.36) | ||

| D−/R− | 318 | 0.40 (0.34, 0.45) | 1.22 (0.96, 1.56) | 0.19 (0.15, 0.24) | 0.74 (0.54, 1.02) | ||

| Stem cell source | |||||||

| PB | 1056 | 0.35 (0.32, 0.38) | Reference | .41 | 0.24 (0.21, 0.26) | Reference | .40 |

| BM | 405 | 0.36 (0.31, 0.41) | 1.09 (0.88, 1.35) | 0.25 (0.21, 0.29) | 1.12 (0.87, 1.44) | ||

| Transplant period | |||||||

| 2005-2012 | 695 | 0.32 (0.28, 0.35) | Reference | .099 | 0.26 (0.23, 0.29) | Reference | .027 |

| 2013-2018 | 766 | 0.38 (0.34, 0.42) | 1.17 (0.97, 1.41) | 0.23 (0.19, 0.26) | 0.78 (0.63, 0.97) | ||

Based on the multivariable proportional subdistribution hazards model for competing risks adjusted for age, female donor to male recipient, CMV serostatus, and transplant period for relapse, adjusted for age, KPS, and transplant period for NRM, and stratified by matching variables: sex, cytogenetic risk, Ph status, disease stage, and conditioning intensity. The robust sandwich covariance matrix estimate was used to adjust for within-center correlation.

Patients who had missing values were included in the model when the variable was covariates, but were excluded when the variable was predictor of interest.

In the subgroup analysis, no differences were noted in either disease relapse or NRM when recipients of Haplo and MUD HCT were compared based on intensity of the conditioning regimen, CR1 status, Philadelphia-chromosome status, and graft source (supplemental Table 4).

Acute and chronic GVHD

Acute and chronic GVHD rates and severity were not different in patients undergoing Haplo or MUD transplantation (Tables 4 and 5). In multivariable analysis, patients who received transplants using a BM graft as their graft source experienced lower rates of grade II-IV acute GVHD compared with those who received transplants using PBSCs (HR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.55-0.87; P < .001) (Table 4). Rates of chronic GVHD were lower in patients with KPS ≤ 80% (HR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.58-0.98; P = .033) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Acute GVHD

| n | Grade II-IV acute GVHD | Grade III-IV acute GVHD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100-d (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)* | P * | 100-d (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)* | P * | ||

| Donor type | |||||||

| MUD | 974 | 0.33 (0.30, 0.36) | Reference | .21 | 0.12 (0.10, 0.14) | Reference | .11 |

| Haplo | 487 | 0.32 (0.28, 0.37) | 1.13 (0.93, 1.38) | 0.14 (0.11, 0.17) | 1.30 (0.94, 1.80) | ||

| Recipient age, y | |||||||

| <30 | 579 | 0.36 (0.32, 0.40) | Reference | .068 | 0.15 (0.12, 0.18) | Reference | .07 |

| 30-39 | 281 | 0.32 (0.26, 0.37) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.10) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.17) | 0.82 (0.56, 1.22) | ||

| 40-54 | 350 | 0.33 (0.28, 0.38) | 0.86 (0.68, 1.09) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) | 0.63 (0.42, 0.94) | ||

| ≥55 | 251 | 0.27 (0.22, 0.33) | 0.69 (0.52, 0.92) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) | 0.61 (0.38, 0.98) | ||

| KPS † | |||||||

| 90-100 | 978 | 0.33 (0.30, 0.36) | Reference | 1.00 | 0.14 (0.11, 0.16) | Reference | .16 |

| ≤80 | 388 | 0.33 (0.28, 0.38) | 1.00 (0.81, 1.23) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) | 0.77 (0.53, 1.11) | ||

| ALL subtype | |||||||

| B-ALL | 1044 | 0.33 (0.30, 0.36) | Reference | .94 | 0.13 (0.11, 0.15) | Reference | .65 |

| T-ALL | 322 | 0.31 (0.26, 0.36) | 1.04 (0.82, 1.33) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) | 0.89 (0.58, 1.36) | ||

| Other | 95 | 0.35 (0.25, 0.45) | 1.03 (0.73, 1.43) | 0.15 (0.09, 0.24) | 1.19 (0.70, 2.02) | ||

| Months from diagnosis to HCT | |||||||

| ≤6 | 398 | 0.33 (0.28, 0.38) | Reference | .44 | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) | Reference | .33 |

| >6-12 | 510 | 0.35 (0.30, 0.39) | 1.16 (0.91, 1.48) | 0.13 (0.10, 0.16) | 1.34 (0.90, 2.01) | ||

| >12 | 553 | 0.31 (0.27, 0.35) | 1.05 (0.78, 1.43) | 0.13 (0.11, 0.16) | 1.31 (0.79, 2.16) | ||

| HCT Comorbidity Index † | |||||||

| 0 | 147 | 0.35 (0.28, 0.43) | Reference | .90 | 0.14 (0.09, 0.20) | Reference | .68 |

| 1-2 | 92 | 0.37 (0.27, 0.47) | 1.10 (0.73, 1.66) | 0.16 (0.09, 0.24) | 1.21 (0.62, 2.36) | ||

| >2 | 94 | 0.41 (0.31, 0.51) | 1.07 (0.64, 1.78) | 0.12 (0.06, 0.19) | 0.88 (0.39, 2.00) | ||

| Donor age, y † | |||||||

| <30 | 342 | 0.38 (0.33, 0.43) | Reference | .42 | 0.14 (0.11, 0.18) | Reference | .90 |

| 30-49 | 443 | 0.34 (0.29, 0.38) | 0.86 (0.68, 1.09) | 0.13 (0.10, 0.16) | 0.92 (0.61, 1.37) | ||

| ≥50 | 127 | 0.35 (0.26, 0.43) | 0.97 (0.71, 1.34) | 0.14 (0.08, 0.20) | 0.92 (0.55, 1.54) | ||

| Female-to-male HCT † | |||||||

| No | 1172 | 0.33 (0.30, 0.36) | Reference | .80 | 0.13 (0.11, 0.15) | Reference | .37 |

| Yes | 262 | 0.34 (0.28, 0.40) | 1.03 (0.80, 1.32) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.16) | 0.82 (0.54, 1.26) | ||

| CMV serostatus † | |||||||

| D+/R− | 581 | 0.31 (0.28, 0.35) | Reference | .88 | 0.11 (0.09, 0.14) | Reference | .43 |

| D−/R− | 130 | 0.34 (0.26, 0.43) | 1.08 (0.78, 1.50) | 0.14 (0.09, 0.21) | 1.23 (0.71, 2.13) | ||

| D−/R− | 366 | 0.33 (0.28, 0.38) | 0.98 (0.78, 1.22) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) | 0.89 (0.60, 1.34) | ||

| D−/R− | 318 | 0.36 (0.31, 0.41) | 1.07 (0.84, 1.35) | 0.15 (0.11, 0.19) | 1.23 (0.84, 1.79) | ||

| Stem cell source | |||||||

| PB | 1056 | 0.35 (0.32, 0.38) | Reference | .001 | 0.13 (0.11, 0.15) | Reference | .14 |

| BM | 405 | 0.26 (0.22, 0.31) | 0.69 (0.55, 0.87) | 0.10 (0.08, 0.14) | 0.76 (0.53, 1.09) | ||

| Transplant period | |||||||

| 2005-2012 | 695 | 0.32 (0.29, 0.36) | Reference | .42 | 0.12 (0.09, 0.14) | Reference | .31 |

| 2013-2018 | 766 | 0.33 (0.30, 0.37) | 1.08 (0.90, 1.30) | 0.13 (0.11, 0.16) | 1.17 (0.87, 1.57) | ||

Based on the multivariable proportional subdistribution hazards model for competing risks adjusted for age and stem cell source, and stratified by matching variables: sex, cytogenetic risk, Ph status, disease stage, and conditioning intensity. The robust sandwich covariance matrix estimate was used to adjust for within-center correlation.

Patients who had missing values were included in the model when the variable was covariates, but were excluded when the variable was predictor of interest.

Table 5.

Chronic GVHD

| n | Any chronic GVHD | Extensive chronic GVHD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-y (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)* | P * | 3-y (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)* | P * | ||

| Donor type | |||||||

| MUD | 974 | 0.30 (0.27, 0.34) | Reference | .50 | 0.13 (0.10, 0.15) | Reference | 1.00 |

| Haplo | 487 | 0.28 (0.24, 0.32) | 1.09 (0.85, 1.39) | 0.09 (0.07, 0.12) | 1.00 (0.69, 1.45) | ||

| Recipient age, y | |||||||

| <30 | 579 | 0.31 (0.27, 0.35) | Reference | .76 | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) | Reference | .57 |

| 30-39 | 281 | 0.28 (0.23, 0.34) | 0.87 (0.67, 1.14) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.17) | 1.24 (0.81, 1.89) | ||

| 40-54 | 350 | 0.30 (0.25, 0.36) | 0.94 (0.73, 1.21) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.16) | 1.02 (0.69, 1.52) | ||

| ≥55 | 251 | 0.28 (0.22, 0.34) | 0.89 (0.65, 1.22) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.15) | 0.86 (0.53, 1.41) | ||

| KPS † | |||||||

| 90-100 | 978 | 0.31 (0.28, 0.34) | Reference | .033 | 0.11 (0.09, 0.14) | Reference | .48 |

| ≤80 | 388 | 0.24 (0.20, 0.29) | 0.75 (0.58, 0.98) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) | 0.87 (0.59, 1.28) | ||

| ALL subtype | |||||||

| B-ALL | 1044 | 0.31 (0.28, 0.34) | Reference | .72 | 0.12 (0.10, 0.14) | Reference | .66 |

| T-ALL | 322 | 0.28 (0.23, 0.33) | 0.97 (0.76, 1.24) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) | 0.91 (0.60, 1.40) | ||

| Other | 95 | 0.25 (0.15, 0.36) | 0.83 (0.52, 1.31) | 0.09 (0.04, 0.17) | 0.71 (0.32, 1.57) | ||

| Months from diagnosis to HCT | |||||||

| ≤6 | 398 | 0.34 (0.29, 0.39) | Reference | .45 | 0.13 (0.10, 0.17) | Reference | .098 |

| >6-12 | 510 | 0.30 (0.25, 0.34) | 0.89 (0.69, 1.14) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.13) | 0.80 (0.52, 1.23) | ||

| >12 | 553 | 0.26 (0.22, 0.30) | 1.04 (0.75, 1.44) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.15) | 1.35 (0.80, 2.26) | ||

| HCT Comorbidity Index † | |||||||

| 0 | 147 | 0.27 (0.19, 0.36) | Reference | .81 | 0.09 (0.05, 0.14) | Reference | .39 |

| 1-2 | 92 | 0.27 (0.18, 0.37) | 1.20 (0.68,2.10) | 0.14 (0.07, 0.22) | 1.72 (0.74, 4.00) | ||

| >2 | 94 | 0.25 (0.16, 0.36) | 1.13 (0.60, 2.13) | 0.13 (0.06, 0.22) | 1.60 (0.65, 3.97) | ||

| Donor age, y † | |||||||

| <30 | 342 | 0.30 (0.25, 0.36) | Reference | .49 | 0.12 (0.09, 0.16) | Reference | .65 |

| 30-49 | 443 | 0.33 (0.29, 0.38) | 1.06 (0.81, 1.40) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.16) | 0.94 (0.60, 1.46) | ||

| ≥50 | 127 | 0.25 (0.18, 0.34) | 0.84 (0.57, 1.24) | 0.08 (0.04, 0.14) | 0.72 (0.35, 1.45) | ||

| Female-to-male HCT † | |||||||

| No | 1172 | 0.30 (0.27, 0.33) | Reference | .95 | 0.12 (0.10, 0.14) | Reference | .83 |

| Yes | 262 | 0.29 (0.23, 0.35) | 1.01 (0.76, 1.34) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) | 1.06 (0.65, 1.71) | ||

| CMV serostatus † | |||||||

| D+/R+ | 581 | 0.29 (0.25, 0.33) | Reference | .94 | 0.11 (0.08, 0.14) | Reference | .88 |

| D+/R− | 130 | 0.30 (0.22, 0.38) | 0.96 (0.66, 1.39) | 0.13 (0.08, 0.20) | 1.07 (0.62, 1.84) | ||

| D−/R+ | 366 | 0.28 (0.23, 0.33) | 0.98 (0.75, 1.27) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.15) | 1.00 (0.65, 1.53) | ||

| D−/R− | 318 | 0.33 (0.28, 0.39) | 1.06 (0.80, 1.40) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.15) | 0.86 (0.55, 1.34) | ||

| Stem cell source | |||||||

| PB | 1056 | 0.30 (0.27, 0.33) | Reference | .72 | 0.12 (0.10, 0.14) | Reference | .25 |

| BM | 405 | 0.28 (0.24, 0.33) | 0.96 (0.76, 1.20) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.13) | 0.80 (0.55, 1.17) | ||

| Transplant period | |||||||

| 2005-2012 | 695 | 0.32 (0.28, 0.36) | Reference | .009 | 0.14 (0.12, 0.17) | Reference | <.001 |

| 2013-2018 | 766 | 0.27 (0.24, 0.31) | 0.77 (0.63, 0.94) | 0.09 (0.07, 0.11) | 0.55 (0.40, 0.77) | ||

Based on the multivariable proportional subdistribution hazards model for competing risks adjusted for KPS, months from diagnosis to HCT, and transplant period, and stratified by matching variables: sex, cytogenetic risk, Ph status, disease stage, and conditioning intensity. The robust sandwich covariance matrix estimate was used to adjust for within-center correlation.

Patients who had missing values were included in the model when the variable was covariates, but were excluded when the variable was predictor of interest.

Incidence and severity of acute GVHD and chronic GVHD in subgroup analysis are summarized in supplemental Table 5A-B. The only subsets with a statistically meaningful difference in the incidence of grade III-IV acute GVHD were in recipients of MUD vs Haplo HCT, MUD as the reference group, in the subset of patients who received RIC (with HR = 2.19; 95% CI, 1.08-4.44; P = .030) or PBSC as the graft source (with HR = 1.49; 95% CI, 1.02-2.18; P = .041).

Causes of death

There were no significant differences in cause-specific death between HaploHCT and MUD HCT for disease relapse/progression (P = .78), infections (P = .82), or organ failure (P = .20). However, patients of Haplo HCT were less likely to die of GVHD compared with MUD recipients (HR = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.26-0.76; P = .003).

Discussion

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed and compared survival and other transplant outcomes of patients with ALL who underwent haploidentical transplantation with PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis (data from TCT-RC, ALWP, and EBMT), with patients who received a MUD transplant (data from ALWP and EBMT) during the same period of time. We matched (1:2 ratio) a cohort of patients with ALL who underwent HaploHCT (n = 506) or MUD transplants (n = 1012) for factors known to predict transplant outcome.1,4,5,23,24 Posttransplant survival was adjusted for other factors, independent of donor type including age, KPS, time from diagnosis to transplant, and stem cell type. Our results indicated that in patients with ALL, OS after HaploHCT with PTCy was comparable to MUD HCT with conventional GVHD prophylaxis (with or without ATG), regardless of the intensity of the conditioning regimen.

In agreement with recently published data by Shem-Tov et al from the ALWP of EBMT,25 our analysis demonstrated that outcomes of alloHCT from haploidentical donors were comparable to MUD transplants for ALL patients. In the current study, we further demonstrated that outcomes in HaploHCT were not different from MUD HCT regardless of conditioning intensity, Philadelphia-chromosome status, and PBSCs as graft source. However, similar to what was previously reported by Bashey et el,32 when PBMC was used as the graft source, a statistically significant increase in the incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD was detected in recipients of HaploHCT. Although our results need to be further investigated, our analysis suggests that PTCy has a more substantial contribution to lowering the incidence of acute GVHD when BM is used as the graft source, possibly due to the lower number of alloreactive T cells in the BM compared with the mobilized PB. In our analysis, rate of acute GVHD was lower in female donor to male recipient in HaploHCT compared with MUD, suggesting that PTCy-based therapy could impact high rates of acute GVHD in female-to-male HCT; however, this was not the case in chronic GVHD.

Overall, the incidence of acute and chronic GVHD was similar after Haplo or MUD HCT, but the mortality rate related to GVHD was higher in patients who received transplantation from a MUD with standard GVHD prophylaxis. The similarity in GVHD rate could be at least partly explained by the intensive GVHD prophylaxis including in vivo T-cell depletion with ATG in a majority of patients in the MUD cohort. It is important to emphasize that in the study by Shem-Tov et al, the incidence of acute and chronic GVHD was not different in Haplo vs unrelated donors. However, 15% of patients in the HaploHCT cohort were given PTCy and ATG, whereas in our study, we limited our analysis to a more homogenous group of patients who received PTCy alone as the GVHD prophylaxis. In this study, patients undergoing HaploHCT were more likely to develop grade III-IV GVHD compared with MUD recipients in subgroup analyses of RIC and PBSCs.

Although the present study is 1 of the first comprehensive comparisons of outcomes of Haplo and MUD HCT in patients with ALL, it has several limitations. Being at least in part an EBMT registry-based study, some of the key elements including minimal residual disease testing, platelet engraftment, and response to prior treatment and HCT Comorbidity Index (77% missing) were partially missing. Although every attempt was made to match or adjust for factors important to predict transplant outcomes, our analysis carried the inherited biases of a retrospective analysis. The wide range of conditioning intensity that existed within the 2 main groups (MAC and RIC) represented another layer of heterogeneity, adding another bias in this comparative study.

There is an increasing interest, and there are promising results, in the use of PTCy as GVHD prophylaxis after alloHCT.33-35 However, data allowing the comparison between transplant outcomes after Haplo and MUD HCT, using PTCy as GVHD prophylaxis, were not available for our analysis, and a comparison between Haplo and MUD HCT with the same GVHD prophylaxis is needed and remains to be investigated. Lastly, HaploHCT has been performed in a smaller number of transplant centers (100 centers), whereas MUD HCT was performed in more centers (201 centers), representing a normal clinical practice across different small-, mid-, and large-sized transplant centers. The center effect on HCT outcomes among Haplo and MUD recipients is warranted and will be important.

In conclusion, in this large multicenter retrospective analysis, outcomes of patients with ALL undergoing transplantation from a haploidentical donor with PTCy were comparable with those undergoing 8 of 8 MUD HCT using conventional GVHD prophylaxis, with or without ATG. Prospective studies with intention to treat are required to confirm these results.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgment

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA033572 (Biostatistics Core).

Footnotes

Data-sharing requests may be e-mailed to the corresponding author, Monzr M. Al Malki, at malmalki@coh.org.

Authorship

Contribution: M.M.A.M., M.M., S.O.C., and A.N. conceived the presented idea and supervised the work; D.Y. and M.L. performed the statistical analysis; S.M. wrote the manuscript with support from M.M.A.M., S.O.C., and A.N.; and all other authors provided critical feedback, helped shape the research, discussed the results, and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Monzr M. Al Malki, Department of Hematology and HCT, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1500 Duarte Rd, Duarte, CA 91010; e-mail: malmalki@coh.org.

References

- 1.Cornelissen JJ, van der Holt B, Verhoef GE, et al. ; Dutch-Belgian HOVON Cooperative Group . Myeloablative allogeneic versus autologous stem cell transplantation in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first remission: a prospective sibling donor versus no-donor comparison. Blood. 2009;113(6):1375-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fielding AK, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. ; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group . Outcome of 609 adults after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); an MRC UKALL12/ECOG 2993 study. Blood. 2007;109(3):944-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, et al. In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993). Blood. 2008;111(4):1827-1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas X, Boiron JM, Huguet F, et al. Outcome of treatment in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: analysis of the LALA-94 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4075-4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S, Cho B-S, Kim S-Y, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first complete remission enhances graft-versus-leukemia effect in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: antileukemic activity of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(9):1083-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ottinger HD, Ferencik S, Beelen DW, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: contrasting the outcome of transplantations from HLA-identical siblings, partially HLA-mismatched related donors, and HLA-matched unrelated donors. Blood. 2003;102(3):1131-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gragert L, Eapen M, Williams E, et al. HLA match likelihoods for hematopoietic stem-cell grafts in the U.S. registry. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):339-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayraktar UD, Champlin RE, Ciurea SO. Progress in haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(3):372-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansen KA, Schneider JF, McCaffree MA, Woods GL; Council on Science and Public Health, American Medical Association . Efforts of the United States’ National Marrow Donor Program and Registry to improve utilization and representation of minority donors. Transfus Med. 2008;18(4):250-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabricius WA, Ramanathan M. Review on haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies. Adv Hematol. 2016;2016:5726132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs EJ. Haploidentical transplantation for hematologic malignancies: where do we stand? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2012;2012:230-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szydlo R, Goldman JM, Klein JP, et al. Results of allogeneic bone marrow transplants for leukemia using donors other than HLA-identical siblings. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(5):1767-1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luznik L, O’Donnell PV, Symons HJ, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(6):641-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Donnell PV, Luznik L, Jones RJ, et al. Nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation from partially HLA-mismatched related donors using posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8(7):377-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciurea SO, Mulanovich V, Saliba RM, et al. Improved early outcomes using a T cell replete graft compared with T cell depleted haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(12):1835-1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciurea SO, Champlin RE. Donor selection in T cell-replete haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: knowns, unknowns, and controversies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(2):180-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh N, Karmali R, Rocha V, et al. Reduced-intensity transplantation for lymphomas using haploidentical related donors versus HLA-matched sibling donors: a Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(26):3141-3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanate AS, Mussetti A, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, et al. Reduced-intensity transplantation for lymphomas using haploidentical related donors vs HLA-matched unrelated donors. Blood. 2016;127(7):938-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salvatore D, Labopin M, Ruggeri A, et al. Outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from unmanipulated haploidentical versus matched sibling donor in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission with intermediate or high-risk cytogenetics: a study from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2018;103(8):1317-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Battipaglia G, Boumendil A, Labopin M, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical versus HLA-matched sibling allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia: a retrospective study on behalf of the ALWP of the EBMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54(9):1499-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu Z, Wang L, Yuan L, et al. Similar outcomes after haploidentical transplantation with post-transplant cyclophosphamide versus HLA-matched transplantation: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8(38):63574-63586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinato DJ, Howlett S, Ottaviani D, et al. Association of prior antibiotic treatment with survival and response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srour SA, Milton DR, Bashey A, et al. Haploidentical transplantation with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(2):318-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santoro N, Ruggeri A, Labopin M, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical stem cell transplantation in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a study on behalf of the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the EBMT. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shem-Tov N, Peczynski C, Labopin M, et al. Haploidentical vs. unrelated allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission: on behalf of the ALWP of the EBMT. Leukemia. 2020;34(1):283-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giralt S, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning regimen workshop: defining the dose spectrum. Report of a workshop convened by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(3):367-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825-828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan KM, Agura E, Anasetti C, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease and other late complications of bone marrow transplantation. Semin Hematol. 1991;28(3):250-259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84(408):1074-1078. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515-526. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Scheike TH, Zhang M-J. Checking Fine and Gray subdistribution hazards model with cumulative sums of residuals. Lifetime Data Anal. 2015;21(2):197-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bashey A, Zhang MJ, McCurdy SR, et al. Mobilized peripheral blood stem cells versus unstimulated bone marrow as a graft source for T-cell-replete haploidentical donor transplantation using post-transplant cyclophosphamide. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(26):3002-3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruggeri A, Labopin M, Bacigalupo A, et al. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in HLA matched sibling or matched unrelated donor transplant for patients with acute leukemia, on behalf of ALWP-EBMT. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah MV, Saliba RM, Rondon G, et al. Pilot study using post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy), tacrolimus and mycophenolate GVHD prophylaxis for older patients receiving 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54(4):601-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deotare U, Atenafu EG, Loach D, et al. Reduction of severe acute graft-versus-host disease using a combination of pre transplant anti-thymocyte globulin and post-transplant cyclophosphamide in matched unrelated donor transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(3):361-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.