Summary

Redox balance is essential for normal brain, hence dis-coordinated oxidative reactions leading to neuronal death, including programs of regulated death, are commonly viewed as an inevitable pathogenic penalty for acute neuro-injury and neurodegenerative diseases. Ferroptosis is one of these programs triggered by dyshomeostasis of three metabolic pillars—iron, thiols and polyunsaturated phospholipids. This review is focused on: i) lipid peroxidation (LPO) as the major instrument of cell demise, ii) iron as its catalytic mechanism, and iii) thiols as regulators of pro-ferroptotic signals, hydroperoxy-lipids. Given the central role of LPO, we discuss the engagement of selective and specific enzymatic pathways vs. random free radical chemical reactions in the context of the phospholipid substrates, their biosynthesis, intracellular location and related oxygenating machinery as participants in ferroptotic cascades. These concepts are discussed in lieu of emerging neuro-therapeutic approaches controlling intracellular production of pro-ferroptotic phospholipid signals and their non-cell-autonomous spreading leading to ferroptosis-associated necroinflammation.

Keywords: regulated cell death, neurodegeneration, cerebral ischemia, traumatic brain injury, cerebral hemorrhage, redox lipidomics, phospholipid, glutathione peroxidase 4, lipoxygenase

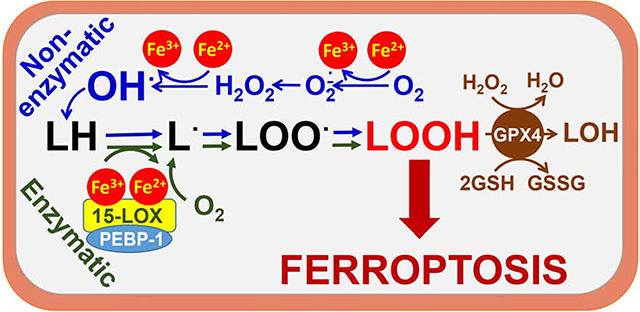

Graphical Abstract

Bayır et al., review ferroptotic death resulting from lipid peroxidation triggered by failure to coordinate iron, lipid and thiol metabolism. Despite several deciphered genetic/biochemical mechanisms, involvement of free radical chemistry is conceivable. Appreciation of selectivity and specificity of these contributory pathways will strongly affect development of anti- and pro-ferroptotic therapies.

Achieving life is not the equivalent of avoiding death.

-Ayn Rand

Introduction

The compatibility and even the necessity of death for the continuation of harmonized life has been allegorically emphasized by many famous poets and artists. Surprisingly, the necessity of death as a physiological mechanism has not been commonly accepted until recently, in spite of the fact that it has been recognized as an evolutionary conserved factor maintaining the health of cells, organismal populations and communities. The requirement of cell demise has become obvious with the discovery of several genetically predetermined programs of regulated death. Conceptualized and described less than a decade ago, ferroptosis is one of these programs that engages three major metabolic pathways operated by thiols, lipid peroxidation, and iron (Dixon et al., 2012a). In the absence of characteristic morphological features of ferroptotic death as well as readily detectable biomarkers, there is a commonly accepted functional definition of ferroptosis as an iron-dependent lipid peroxidation-driven and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)-inhibitable process leading to cell death preventable by select anti-ferroptotic compounds (most commonly, ferrostatin-1 [Fer-1]) (Dixon et al., 2012b; Gaschler et al., 2018; Skouta et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2014b; Yang and Stockwell, 2016).

In spite of the dramatic outcome of this program—cell death—the biological role of ferroptosis is not completely understood (Stockwell et al., 2017), although several speculations have been made. According to one school of thought, ferroptotic death is a penalty imposed on a particular cell within a multicellular community that exhibits severe and irreparable dis-coordinated systems of redox regulation. This leads to the excessive accumulation of pro-oxidant metabolites that may represent a threat for the healthy environment of the community (Kagan et al., 2019). This may manifest in several ways; for example, excessive production of lipid mediators, acting as opposing or controversial signals, may disrupt essential biological functions (Fig. 1). To prevent this confusion and equivocal signaling, the program of ferroptotic elimination is triggered. This program operates with the same major components of the protein machinery involved in the generation of lipid mediators but with slightly modified substrates and products of the enzymatic process. As an example, the dis-coordinated production of the canonic lipid mediators (e.g., eicosanoids) catalyzed by one or several representatives of the lipoxygenase (LOX) family (5-, 8-, 12-, 15-LOX) leads to the assembly of 15-LOX and phosphatidylethanolamine binding protein 1 (PEBP1) into 15-LOX/PEBP1 enzymatic complexes. These complexes generate death signals by changing the LOX substrate selectivity (arachidonic acid [AA] esterified to phosphatidylethanolamine [PE] instead of free AA) and product specificity (15-hydroperoxy AA-containing PE instead of oxygenated forms of AA) causing cellular demise (Fig. 1) (Kagan et al., 2017; Wenzel et al., 2017).

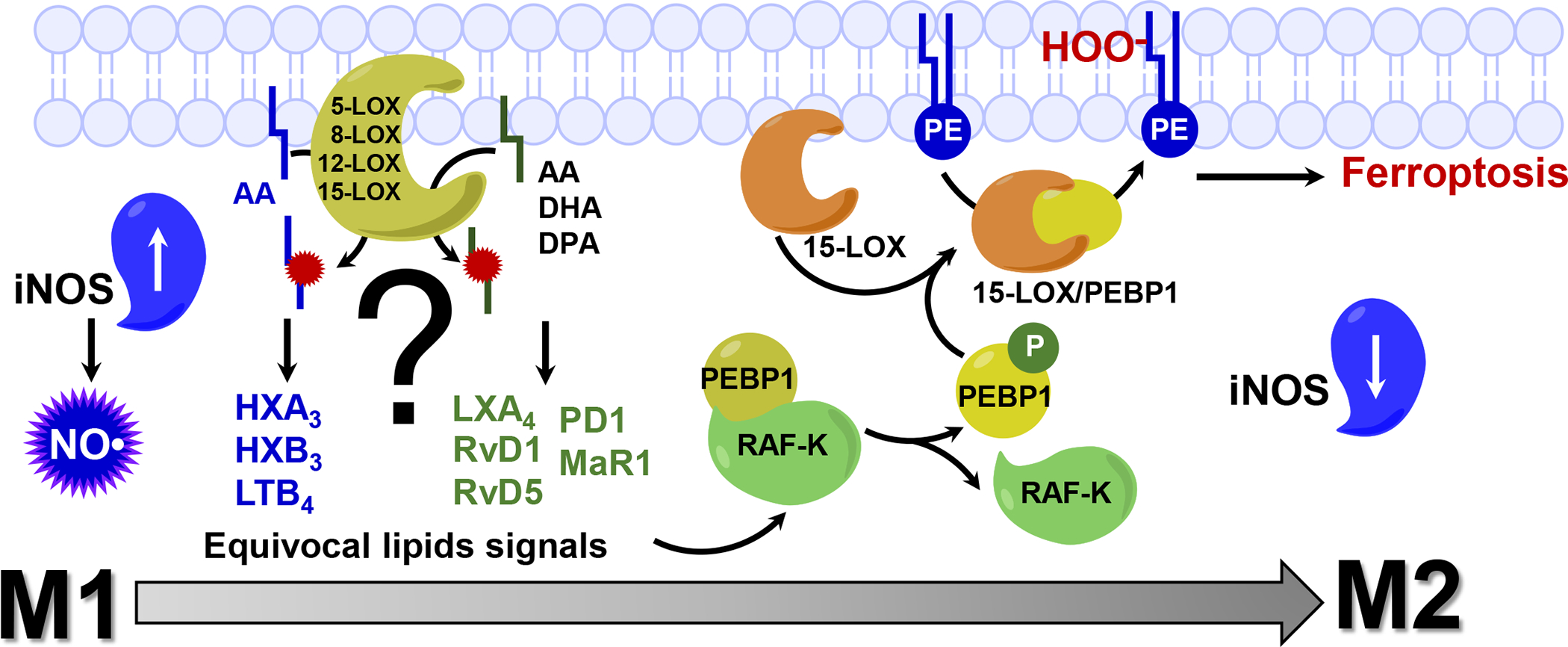

Fig. 1. Lipoxygenases (LOXs) catalyze the formation of essential lipid mediators with pro- and anti-inflammatory propensities.

In cells, essential signaling molecules, lipid mediators, are formed by lipoxygenases (LOX) from free PUFA (w-6 and w-3 series). These oxidation products coordinate many metabolic processes and cell responses, including inflammation. 12-LOX and 5-LOX are involved in the generation of pro-inflammatory mediator leukotriene B4 (LTB4) from arachidonic acid (AA). The first step in biosynthesis of hepoxilins A3 and B3 (HXA3 and HXB3) is catalyzed by 12-LOX. 15-LOX is implicated in biosynthesis of anti-inflammatory lipid mediators such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) derived resolvins (RvD1 and RVD5), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) derived protectin D1, AA-derived lipoxins (LXA3). Maresin R1 (MaR1), a DHA-derived lipid mediator generated by 12-LOX, stimulates switch of macrophages from M1 to M2 type. Dysregulated production of equivocal lipid signal by LOXs may lead to the triggering of a specialized program of cell death, ferroptosis, in dis-coordinated cells aberrantly producing confusing signals. Dis-regulation of lipid mediators biosynthesis leads to the assembly and engagement of 15-LOX/PEBP1 enzymatic complexes that start producing pro-ferroptotic death signals. PEBP1 (Phosphatidylethanolamine Binding Protein 1), a scaffold protein, an inhibitor of protein kinase (RAF-K), complexes with 15-LOX, and changes the substrate selectivity of the dioxygenase (AA-PE instead of free AA) and catalyzes a specific oxygenation generating 15-HOO-AA-PE as a ferroptotic cell death signal.

Another example may be related to the regulation of inflammation. Cells of the innate immune system—neutrophils, macrophages, microglia—may be present in several polarization states with substantially different phenotypic manifestations, including different sensitivities to ferroptosis (Kapralov et al., 2020). Interestingly, this may be used as a means of fine-tuning of the inflammatory response. Indeed, professional phagocytes activated to the pro-inflammatory M1 state with a high level of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)/NO• expression display a remarkably high resistance to ferroptosis, whereas alternatively activated pro-resolving M2 cells are highly vulnerable to ferroptotic elimination (Fig. 1). Thus, the numbers and ratio of M1 cells (which generate pro-inflammatory regulators such as cytokines and lipid mediators) to M2 cells (which are a source of anti-inflammatory regulators) may act as a “rheostat” controlling the production of pro-inflammatory vs pro-resolving signals (Dalli et al., 2013). The distinctive sensitivity or tolerance of these cells to ferroptosis may command the context-dependent adaptive changes of the innate immune system to support more aggressive pro-inflammatory vs more pro-resolving anti-inflammatory milieus. Of course, other examples of the functional role(s) of ferroptosis in different types of cells will emerge as our understanding of its role and mechanisms advances. The above examples, however, raise an interesting general question: do differential sensitivity and execution of ferroptosis in specific cell types of a given community represent a mechanism of death, or rather do they represent a reprograming on the level of a cell population? From this point of view, the engagement of the three pillars—iron, thiols, and lipid peroxidation—in the cascade of reprograming events utilizes the major intracellular redox pathways.

The pathophysiological relevance of ferroptosis compared to necrosis is likely due to the “regulated” nature of the ferroptotic program with specific biochemical and genetic mechanisms that can be targeted therapeutically. The pathophysiological relevance of ferroptosis compared to apoptosis is likely defined by the differences in the inflammatory responses associated with these death pathways. Apoptosis is considered strongly anti-inflammatory due to preservation of the plasma membrane integrity along with the hydrolytic “digestion” of the intracellular contents, and generation of apoptotic bodies engulfed by macrophages. Ferroptosis is regarded as one of the pro-inflammatory (necro-inflammatory) regulated cell death pathways characterized by plasma membrane rupture and release of intracellular contents as damage associated molecular patterns (Tonnus et al., 2019).

IRON IN FERROPTOSIS

The chemically reactive, kinetically labile iron pool is directly coordinated by glutathione

Specific mechanisms of ferroptosis are continuing to emerge; however, the thiol-driven regulation seems to be better understood than the roles of iron and lipid peroxidation pathways. In fact, the role of the two major components of the thiol system—GPX4 and reduced glutathione (GSH)—are well-characterized (Forcina and Dixon, 2019; Friedmann Angeli et al., 2014a; Seibt et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2018b). In contrast, specific mechanisms of lipid peroxidation and redox activity of iron in ferroptosis remain less explored in spite of their definitively established importance as discussed below.

The species of iron thought to directly participate in ferroptosis are likely represented by two pools of iron: i) catalytic centers of non-heme iron proteins, e. g. LOX (discussed below), and ii) ferrous iron of the cytosolic labile iron pool (LIP). The LIP is largely defined by what it is not. Most of the iron in mammalian cells (>90%) is in the form of cofactors (heme, iron-sulphur clusters, mono- and diiron centers) and storage pools (ferritin), with the amount of iron as cofactors staying relatively constant over time and the amount of iron in ferritin varying widely (Chakrabarti et al., 2015). The “labile iron pool” is the iron that remains. It is the chemically reactive and kinetically labile pool that can be transferred to mitochondria and used for heme and iron-sulfur cluster synthesis. It can be transferred directly to the active sites of non-heme iron enzymes in the cytosol or to ferritin for storage. It can bind to iron-sensing proteins to affect their activity or stability. Based on the reduction potential of the cytosol, Williams in 1982 suggested that the low-molecular-weight pool of iron in cells is almost exclusively ferrous [Fe(II)] (Williams, 1982). Subsequent experimental evidence confirmed that the LIP is Fe(II) (Kozlov et al., 1992; Yegorov et al., 1993) and is present in concentrations between 0.5 and 5 μM (Esposito et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2006; Petrat et al., 2002). However, under physiological conditions Fe(II) is highly reactive and can catalyze the conversion of endogenously produced hydrogen peroxide to highly reactive intermediate species (Galaris et al., 2019), such as hydroxyl radical (HO•) or a high-valence oxo-ferryl species via the Fenton reaction (Merkofer et al., 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2012). Both of these are predicted to attack and oxidatively damage multiple cellular components, especially lipids containing polyunsaturated fatty acyl chains (PUFAs). It is also possible that iron centers of LOXs catalyze the formation of the primary enzymatic products of lipid peroxidation, hydroperoxy-lipids (L-OOH), while Fe(II) from the LIP participates in the secondary reactions of L-OOH decomposition to produce oxidatively-truncated electrophilic products of lipid peroxidation (see below) (Stoyanovsky et al., 2019). This chemical reactivity of Fe(II) in the LIP is mitigated through coordination by a complex buffer composed of small molecules and iron chaperone proteins.

Many small molecule ligands have been proposed to coordinate cytosolic LIP. Iron (II) exhibits relatively strong interactions with free thiols, including cysteine and GSH. Although Fe(II) binds cysteine, the amino acid is not present in the cytosol at sufficiently high levels to support complex formation. Systematic in vitro evaluation suggests that only GSH exists in the cytosol at the necessary concentrations (2–10 mM) to form complexes with Fe(II) (Hider and Kong, 2013; Hider and Kong, 2011). It is proposed that Fe(II) forms a 1:1 complex with GSH, where the free thiol directly coordinates the iron. Iron speciation plots covering the physiological concentration ranges of GSH (1–10 mM) and iron (0.5–5 μM) indicate that >95% of the cytosolic LIP is predicted to be a Fe(II)-GSH complex. Moreover, a recent empiric study confirms the formation of Fe-GSH complexes in cells (Patel et al., 2019). These quantitative estimates also indicate that only a relatively small fraction of intracellular GSH (~0.1mol%) is engaged in the LIP function in many types of cells, including CNS cells, particularly neurons (Sun et al., 2006).

Iron-glutathione complexes of the labile iron pool are coordinated by PCBP1

The poly(rC)-binding protein (PCBP) family plays a key role in cellular Fe(II) distribution (Philpott and Jadhav, 2019) (Fig. 2). PCBPs are multifunctional adaptor proteins that bind single-stranded nucleic acids, proteins, and iron, affecting the fate of each ligand. PCBP1 and PCBP2 are iron chaperones: they bind iron and can receive or transfer it to other proteins via metal-mediated protein-protein interactions. In cells, PCBPs function by chaperoning iron to/from: transport proteins (divalent metal transporter [DMT1], ferroportin1), storage sites (ferritin), and iron-containing proteins (prolylhydroxylase [PHD], deoxyhypusine hydroxylase [DOHH], hemeoxygenase-1 [HO1], BolA2). In vitro studies using isothermal titration calorimetry indicate both PCBP1 and PCBP2 can coordinate three Fe (II) ions per protomer with low μM affinity (Leidgens et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2008). More recent work demonstrates that GSH is required for the formation of stable iron complexes on PCBP1, both in cells and in model (bio)chemical systems (Patel et al., 2019). PCBPs are structurally comprised of three hnRNP-K-homology (KH) domains, which are ancient, conserved RNA-binding modules (Makeyev and Liebhaber, 2002). The third KH domain of PCBP1 coordinates iron via conserved cysteine and glutamate residues and a molecule of noncovalently bound GSH, indicating that the preferred ligand for PCBP1 is an Fe-GSH complex (Patel et al., 2019). These studies also showed that GSH binding can allosterically stabilize the Fe-PCBP1 complex to facilitate iron transfer to client proteins. In vitro analysis also indicated that PCBP1 can coordinate Fe-GSH molecules with affinities in the sub-μM range, which suggests that much of the cytosolic iron pool is in the form of PCBP1-Fe-GSH complexes.

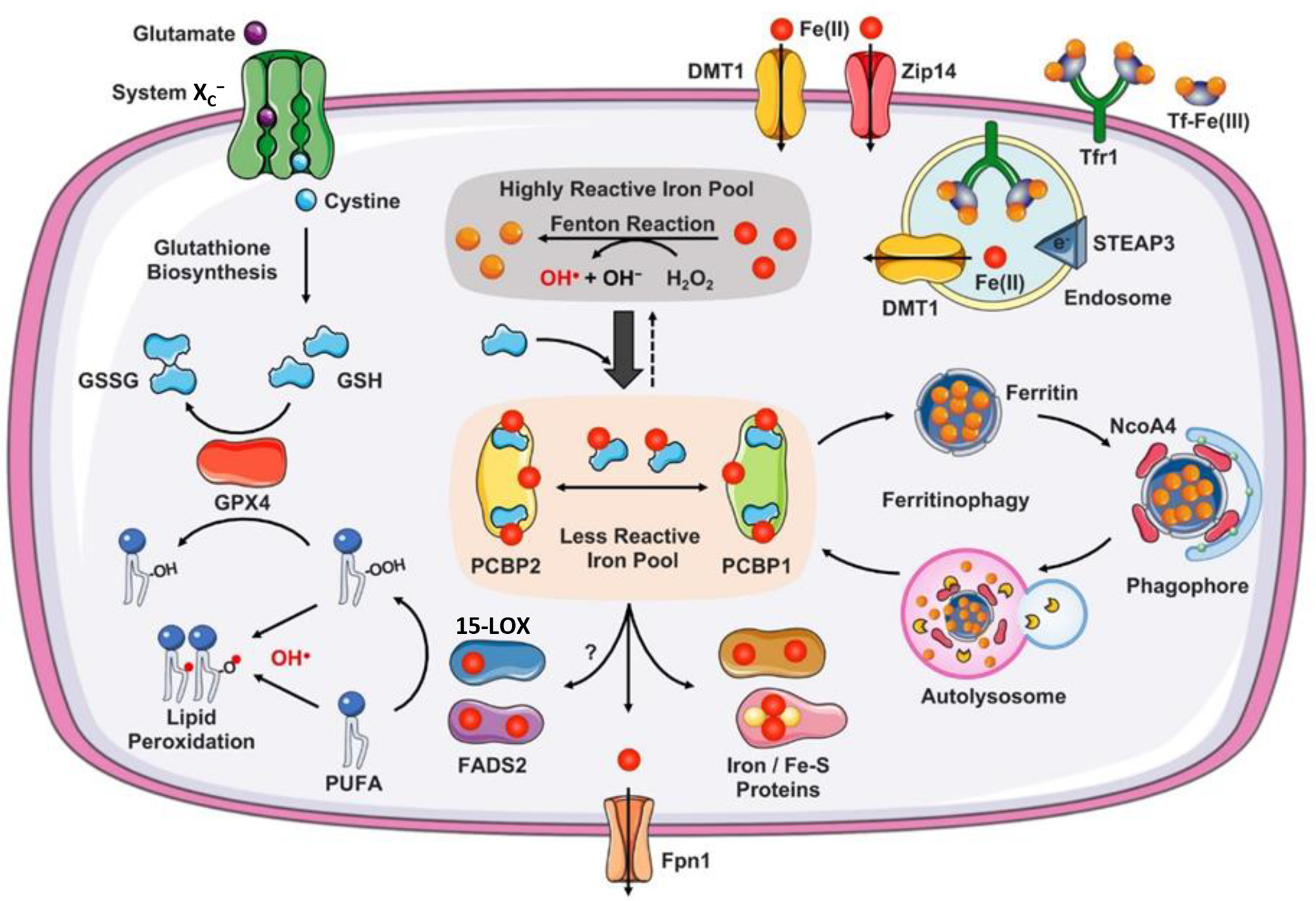

Fig. 2. Iron chaperone limits the chemical reactivity of cytosolic labile iron pool.

Non-transferrin-bound iron is reduced to Fe(II) by ferrireductases at the plasma membrane surface and transported into the cytosol via divalent metal transporter, DMT1, or Zip14. Circulating iron in the form of Fe(III)2-transferrin (Tf) binds to transferrin receptor 1 (Tfr1) on the plasma membrane to form Tf-Tfr1 complex, which is endocytosed. At the low pH of the endocytic vesicle, Fe(III) is released from Tf and ferrireductases (e.g., STEAP3) reduce Fe(III) to Fe(II), which is translocated into the cytosol by DMT1. If it remains free, Fe(II) reacts with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to produce cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals (OH•) via the Fenton reaction. Cytosolic Fe(II) is coordinated by reduced glutathione (GSH) in the cytosolic labile iron pool. PCBP1 and PCBP2 are iron chaperones that play integral roles in intracellular iron trafficking. Structurally PCBPs contain three tandem K-homology domains (KH1–3) that can bind GSH coordinated Fe(II) with high affinity in 1:1 ratio. Under physiological conditions a significant proportion (>90%) of the labile iron pool may be coordinated by PCBPs. PCBP2 binds iron loaded DMT1 to facilitate iron influx, binds heme degrading heme oxygenase to facilitate iron redistribution, and binds Ferroportin (Fpn1) to facilitate iron efflux. PCBP1 (to a lesser extent, PCBP2) binds and delivers iron to ferritin and mono/di-nuclear iron proteins and Fe-S carrier proteins. Ferritin binds to Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 4 (NcoA4) to undergo lysosomal degradation, process referred to as ferritinophagy. Ferritin iron released in the lysosome can be transferred back to the cytosol or transported to mitochondria. PCBPs may also metalate di-iron containing fatty acid desaturases (e.g. FADS2) and mono-iron containing lipoxygenases (e.g. 15-LOX), which are integral in lipid metabolism. FADS2 contributes to the formation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and 15-LOX catalyzes the dioxygenation of PUFAs to generate phospholipid hydroperoxide (PL-OOH). Both PUFA and PL-OOH are the targets of the peroxidation reactions associated with ferroptosis. System XC− imports cystine, which is reduced to cysteine and used to synthesize GSH. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) uses GSH to eliminate lipid peroxides formed in phospholipids containing PUFAs. Arrows indicate promotion; broad arrow indicate higher extent; dotted arrow indicates lesser extent.

PCBP1 limits the chemical reactivity of the cytosolic labile iron pool

Studies demonstrating the coordination of Fe-GSH complexes by PCBP1 suggest that PCBP1 exerts control over the chemical reactivity as well as the trafficking of the labile iron pool. In humans, PCBP1 is uniformly present in many tissues and its expression in different areas of the brain is high (Uhlén et al., 2015) Mice lacking PCBP1 in hepatocytes spontaneously develop steatohepatitis, with accumulation of di- and triglycerides and cholesteryl esters in the liver (Protchenko, 2019). This accumulation of lipid appears to be driven by increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the presence of “unchaperoned” iron. Shifting these animals to diets with very low amounts of iron blocks the development of steatosis and the accumulation of oxidized lipids in the liver. Thus, PCBP1 is required in to limit the chemical reactivity of iron.

The iron chaperone activities of PCBP1 sequester labile iron in ferritin

PCBP1 may also limit the chemical reactivity of the cytosolic LIP by keeping the pool small. PCBP1 was initially identified as an iron chaperone for ferritin (Shi et al., 2008). Ferritin is the major site of iron storage in mammalian cells and is a hollow sphere, composed of 24 subunits of H- and L-chains, that can sequester large amounts of iron as ferric oxyhydroxides. In the brain, all four major cell types (neurons, glia, microglia, and oligodendrocytes) contain ferritin, with glia being the most iron-rich cells (Reinert et al., 2019). PCBP1 can deliver iron to ferritin via a direct, protein-protein interaction that results in iron transfer to the mineral core, likely via pores formed at subunit interfaces. Iron sequestered in ferritin is relatively inert, but cells can mobilize the iron stored in ferritin by directing the oligomer to the lysosome for degradation (Philpott et al., 2017). This process occurs through a specific form of autophagy, referred to as ferritinophagy, which is mediated by the ferritin-specific, autophagic cargo receptor, nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) (Dowdle et al., 2014; Mancias et al., 2015; Mancias et al., 2014). Under conditions of iron deficiency, NCOA4 can also directly bind to ferritin and mediate its incorporation into the autophagosome. Once delivered to the autolysosome, iron liberated from degraded ferritin can be transferred back to the cytosol or, in the case of erythroid precursors, to the mitochondria for heme synthesis.

Cell-based in vitro studies and murine studies of erythropoietic precursors and hepatocytes confirm that efficient storage of iron in ferritin is dependent on PCBP1. In hepatocytes, PCBP1 is needed to maintain intracellular levels of iron and ferritin (Protchenko, 2019). In erythroid precursors, iron trafficking through ferritin is critical for efficient utilization of iron for heme synthesis in the mitochondria (Ryu et al., 2017). Similarly, NCOA4-mediated turnover of ferritin is also required for optimal iron utilization in erythroid precursors. Because the PCBP1- and NCOA4-mediated flux of iron through ferritin is associated with the mobilization of potentially large amounts of stored iron, these processes may have an impact on ferroptosis in some settings. Empiric data to support or refute this hypothesis are scant, and further studies are needed. PCBP1 has been found in neurons, and it has been established that its knockdown or overexpression affect transcriptional and translational regulation of several signaling pathways, cell cycling and apoptosis (Huo et al., 2012) as well as neuronal development (Vidaki et al., 2017). However, the neuronal role of PCBP1 in regulation of iron homeostasis has yet to be established and may represent the subject of future studies. Similarly, additional studies are necessary to clarify the expression, regulation, and function of NCOA4, as well as it is role in ferroptotic cell death in the CNS (Quiles Del Rey and Mancias, 2019).

PCBP1 may deliver iron to client proteins involved in ferroptosis

Client proteins that may receive their iron cofactors from PCBP1 are key mediators of the ferroptotic process. The iron chaperone activities of PCBP1 include the delivery of ferrous ions to mononuclear and dinuclear iron centers. The PHDs that regulate hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1-α contain mononuclear iron centers. PCBP1 can directly interact with PHD2 to transfer iron to its active site. Cells lacking PCBP1 exhibit reduced PHD activity due to loss of the iron cofactor (Nandal et al., 2011). Similarly, PCBP1 can activate the diiron center of DOHH, a monooxygenase that catalyzes the hydroxylation step in the formation of hypusine, a modified amino acid in eIF5a. DOHH and PHD2 are structurally unrelated and yet PCBP1 binds both and the PCBP1-mediated interaction with DOHH is dependent on iron (Frey et al., 2014). Other mononuclear and dinuclear iron centers may also depend on PCBP1 for full metalation. Two classes of enzymes containing nonheme iron centers are integral in lipid metabolism: fatty acid desaturases, which contain a diiron center (Lee et al., 2016), and LOXs, which contain a monoiron center (Boyington et al., 1993). The fatty acid desaturases contribute to the formation of PUFA-containing lipids, which are the targets of the peroxidation reactions associated with ferroptosis. While some PUFAs originate from dietary sources (e.g. Ω-3 FAs, linoleic and linolenic acids), endogenous desaturases contribute to the formation of arachidonoyl- and adrenoyl-PE (AA- and AdA-PE) that are implicated in ferroptosis. LOX, especially the 15-LOX, may directly catalyze the hydroperoxidation of AA- or AdA-containing lipids (Stoyanovsky et al., 2019). Hydroperoxides of AA (HOO-AA) are further metabolized to form signaling molecules (Kuhn et al., 2015), while hydroperoxides of AA-PE (HOO-AA-PE) are proposed to trigger the ferroptotic response. Although PCBP1 has not been directly demonstrated to activate these non-heme enzymes, overall reductions in the non-heme iron content of cells lacking PCBP1 suggest they could be affected. Furthermore, removal of iron from the recombinant human 5-LOX not only altered the catalytic activity of the enzyme, but also impaired its membrane-binding. In cells exposed to increasing amounts of iron, a redistribution of the cytosolic 5-LOX to the nuclear fraction was observed (Dufrusine et al., 2019).

Management of iron through PCBP2

Although PCBP1 and PCBP2 have very similar structures and an 80% identical amino acid sequence, they are independently required for murine embryonic development and have non-overlapping functions in cells. The iron chaperone activities of PCBP2 have been most closely associated with the transfer of iron between transporters or enzymes at cellular membranes. Cell-based models suggest that iron import through DMT1 and export through ferroportin are assisted by PCBP2 and that the iron released through the activity of heme oxygenases at the endoplasmic reticulum is captured by PCBP2 (Yanatori et al., 2016; Yanatori et al., 2017; Yanatori et al., 2014). The chaperone activities of PCBP2 may not be active in all cell types, as HEK cells depleted of PCBP2 exhibit levels of intracellular iron similar to PCBP2-expressing cells (Frey et al., 2014) and developing erythrocytes depleted of PCBP2 also exhibit wild-type levels of iron uptake (Ryu et al., 2017). Similar to PCBP1, PCBP2 is also markedly expressed in different types of neuronal cells where it fulfills different regulatory and signaling functions (Xu et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2002). It was shown that PCBP2 expression increases in neurons and astrocytes after an acute CNS insult (Mao et al., 2016). PCBP2 deficiency enhances glutamate-induced neuronal death while promoting cell cycle arrest in astrocytes. However, its direct relevance to control of iron metabolism and homeostasis in neurons and astrocytes needs further studies.

Mammalian tissues that specialize in iron handling, e.g. the intestinal epithelium, the liver, and the erythron, may exhibit differing management of the cytosolic LIP than cells with more limited metabolic requirements for iron, e.g. neurons or other terminally-differentiated cells. These potential differences in the LIP may render cells more or less susceptible to iron-mediated ROS damage and ferroptotic cell death. Recent studies indicate that GSH has an integral, direct role in the management of the cytosolic LIP that goes beyond its role in supporting glutathione peroxidases (GPXs) or general redox buffering. Further studies will clarify the roles of iron chaperones in the management of the LIP and protection against ferroptosis.

Pathogenic dysregulation of iron in the brain possibly related to ferroptosis.

Increasingly, dysregulation of iron handling and increased pool of the labile redox active iron is viewed as a possible pathogenic mechanism of neurodegeneration related to ferroptosis. In the majority of these cases, the specific mechanisms responsible for the mishandling of iron are not firmly identified, yet positive protective (therapeutic) effects of iron chelators or Fer-1 are considered as strong evidence supporting the role of ferroptosis. Examples of this type are numerous but a direct mechanistic understanding of how iron dyshomeostasis translates into specific disease pathogenesis is still missing in most cases. Among several recent examples, neuroferritinopathies associated with alterations in the L-ferritin gene that increase the cytosolic pool of labile iron (Cozzi et al., 2019) cause the formation of ferritin aggregates, oxidative damage, and the onset of a senescence phenotype, which is particularly severe in neurons. In this spontaneous senescent neuroferritinopathy-based model, cells are susceptible to ferroptotic death (Cozzi et al., 2019). Another pathological example involving a possible ferroptotic mechanism is intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), whereby neurological deficits, memory impairment, and brain atrophy were reduced by Fer-1 treatment (Chen et al., 2019). Temporal lobe epilepsy following kainic acid (KA) in rats demonstrated sensitivity to the Fer-1 treatment that prevented the initiation and progression of ferroptosis in the hippocampus and rescued cognitive function in KA-induced TLE in rats (Ye et al., 2019). Friedreich’s ataxia is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by ataxia and sensory loss associated with by GAA repeat expansions in the first introns of both alleles of the FXN gene. Its pathology leads to the decreased expression of the encoded protein, frataxin, which is required for iron-sulfur-cluster biosynthesis in mitochondria (Santos et al., 2010). It has been demonstrated that frataxin deficiency triggers mitochondrial dysfunction and iron accumulation as well as increased oxidative stress, and these typical manifestations were preventable by inhibitors of ferroptosis (Cotticelli et al., 2019). Based on the sensitivity of the spinal cord trauma to iron chelators (e.g. deferoxamine) or ferroptosis inhibitors (eg, SRS 16–86), the pathogenic engagement of ferroptosis has been proposed (Yao et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019a). Based on partially understood crosstalk mechanisms of proteins pathologically associated with neurodegeneration, such as α-synuclein, tau, and amyloid precursor protein with iron homeostatic proteins, conclusions have been made on the participatory role of ferroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Masaldan et al., 2019). While the above-mentioned and other similar cases certainly deserve further thorough research attention, it is difficult to definitively conclude that ferroptosis is the leading cause of their pathogenic mechanisms. As will be discussed in the next section, a highly selective and specific enzymatically catalyzed phospholipid peroxidation by non-heme iron-proteins (LOXs) rather than disorganized iron homeostasis, is required for the fulfillment of the ferroptotic death program. Therefore, focused studies of iron chaperones participating in the delivery of iron to LOXs may be particularly important.

LIPID PEROXIDATION IN FERROPTOSIS

In spite of the unambiguous leading role of lipid peroxidation as the major instrument of ferroptosis, its mechanisms, and the role of iron in its initiation and regulation are poorly understood (Dixon et al., 2012b; Doll and Conrad, 2017; Latunde-Dada, 2017). In fact, whether the lipid peroxidation process has a strictly controlled enzymatic nature or develops as a poorly controlled free radical reaction still remains the subject of active discussions (Stoyanovsky et al., 2019; Zilka et al., 2017a). To a large extent, this is due to the lack of adequate methodology for studying ferroptotic lipid peroxidation, which led researchers to use simple and readily available semi-quantitative and nonspecific protocols rather than precise and accurate measurements and quantitative characterizations.

Adequacy of the analytical tools and methods to assess lipid peroxidation and its substrates.

The cell lipidome includes tens of thousands of individual species of lipids that vary markedly in their abundance, intracellular distribution, physical organization, and functions (Braverman and Moser, 2012; Lordan et al., 2017; Mejia and Hatch, 2016). A significant part of lipidome is represented by molecular species of lipids containing readily oxidizable PUFA residues (Guichardant et al., 2011). The oxidation process—enzymatic or non-enzymatic—begins with the abstraction of a bis-allylic hydrogen, rearrangement of the resonance radical structure, addition of the molecular oxygen leading to the peroxyl radical, and the formation of the primary molecular product, L-OOH (Fig. 3). A relatively low dissociation energy of the O-O bond (Porter et al., 1995; Pratt et al., 2011) leads to the L-OOH cleavage yielding a number of secondary oxidation products, frequently with a shortened carbon chain and an oxygen-containing functionality with highly electrophilic propensities (Fig. S1). The most commonly formed electrophiles include epoxy, oxo-, or aldehydic groups that may be located at different sites of the hydrocarbon chain (Fig. S1). The electrophilic group may be formed on either truncated phospholipid or on the leaving shorter PUFA fragment (Fig. S1).

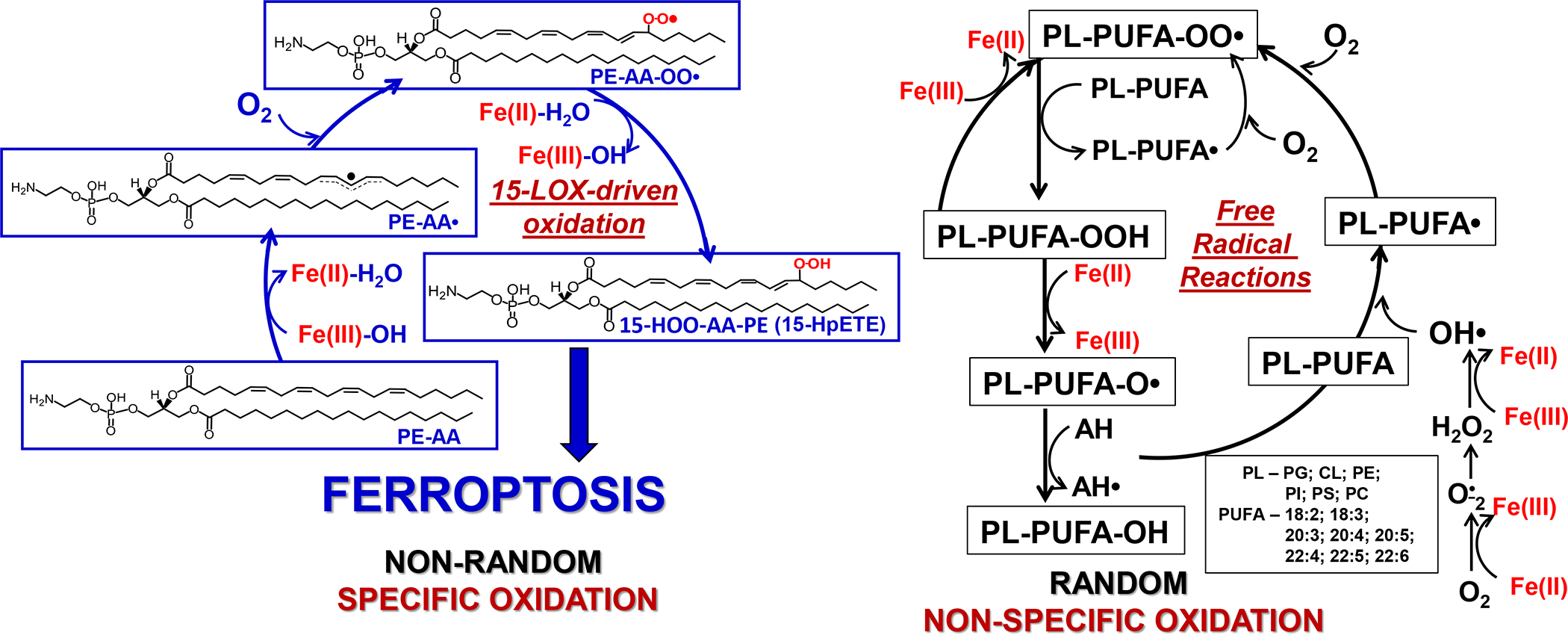

Fig. 3. Principle schemas of the reaction mechanism and specific features of enzymatic vs random non-enzymatic peroxidation of PUFA phospholipids.

Both enzymatic - selective (left panel) and non-enzymatic - non-selective (right panel) lipid peroxidation begins with the abstraction of bis-allylic hydrogen, rearrangement of the resonance radical structure, addition of the molecular oxygen leading to the generation of peroxyl radical and the formation of the primary molecular product, hydroperoxy-lipid. During random oxidation all PUFA containing phospholipids undergo oxidation whereby the rates are proportional to the number of readily abstractable bis-allylic H, resulting in the accumulation of a highly diversifies pattern of oxidation products with the dominance of oxygenated PUFA-PLs with 6, 5, 4, 3, and 2 double bonds. LOX-driven oxidation results in the preferential generation of specific AA-PE oxidation yielding 15-HOO-AA-PE. The selectivity and specificity of the reaction is due to the organization of the catalytic site in 15-LOX/PEBP1 complex (Wenzel et al., 2017) resulting in highly selective, site-specific and stereo-selective product- 15-HOO-AA-PE. The substrate radical rearrangement is accompanied by the addition of molecular oxygen delivered via a special channel in the protein. Non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation proceeds by a free radical chain reaction. This process is not specific and non-selective.

Given the huge diversification of the lipidome and a large number of possible oxidation products, full characterization of the oxidation process and its products represents a daunting task (Tyurina et al., 2019). Assuming that one or more of these diversified lipid peroxidation products may act as direct executioners of ferroptotic death, ideally all of these oxidation products should be characterized using contemporary high resolution liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) platforms (Kagan et al., 2017; Tyurina et al., 2019; Wenzel et al., 2017). Because redox lipidomics is still in the initial stages of its development, this ideal analytical approach is not always possible, and “much easier” simplified protocols, frequently inadequate, are commonly utilized as surrogate measures of lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis (Friedmann Angeli et al., 2014a).

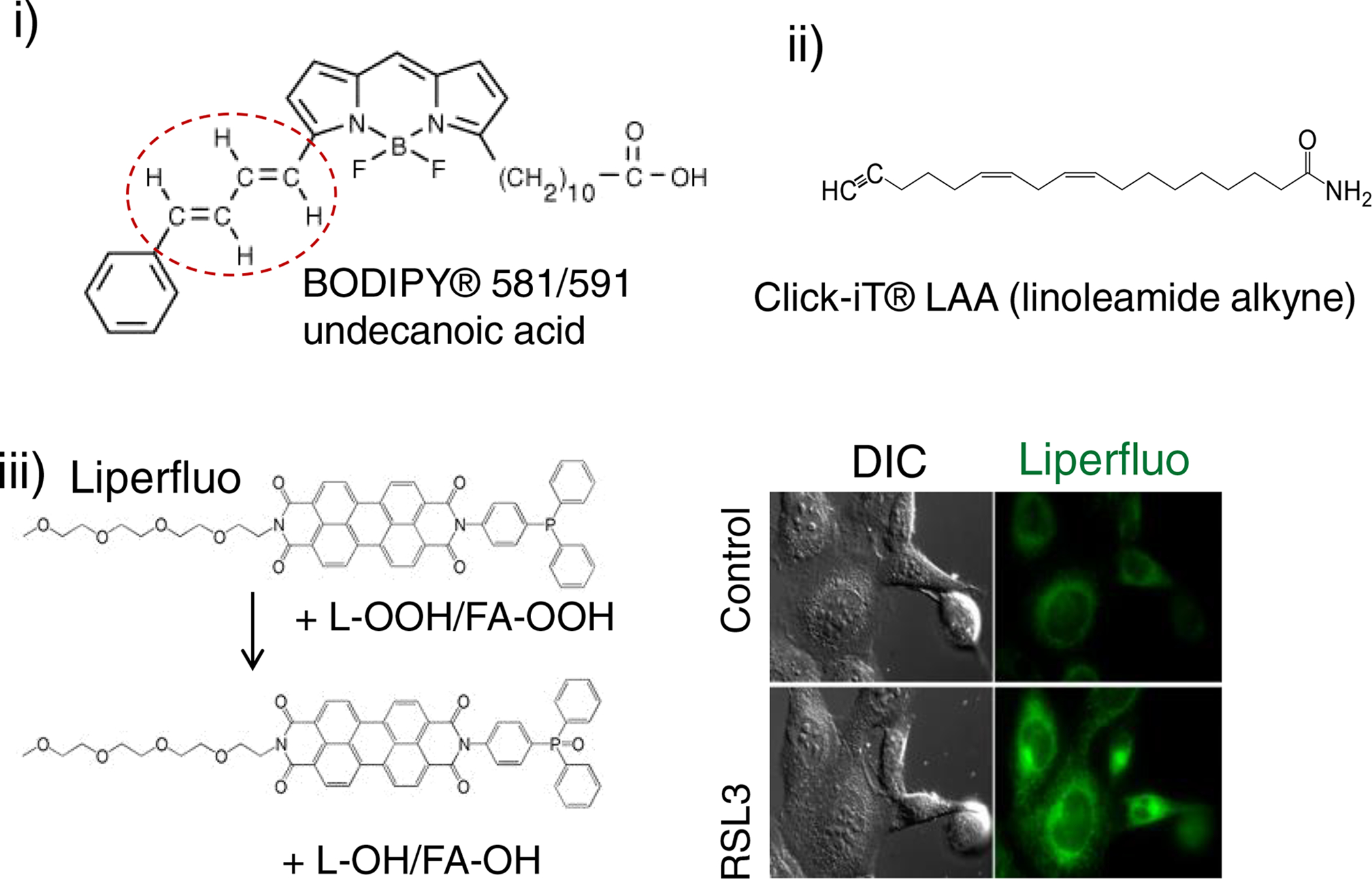

Leaving aside an almost “ancient” protocol with thiobarbituric reactive substances (TBARS or malondialdehyde assay) that gives nonspecific positive responses with many compounds that have aldehyde-containing functionalities (Kohn and Liversedge, 1944) and thus proven to be completely non-applicable for any metabolic system (cells, tissues of model organisms) (Janero, 1990), there are only three major approaches currently used to assess lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis research: i) fluorescence assay of BODIPY (also called Lipid ROS); ii) linoleate-based Click-iT® LAA (linoleamide alkyne) lipid peroxidation assay, and iii) Liperfluo fluorogenic assay of hydro-peroxy-containing groups (Fig. 4). All three of these protocols suffer from substantial deficiencies. The BODIPY® 581/591 undecanoic acid assay demonstrates a strong correlation with the fluorescence activation due to oxidation of the BODIPY® 581/591 fragment of the probe (MacDonald et al., 2007). The oxidation is catalyzed by some kind of pro-oxidant activity towards a non-lipid substrate clearly unrelated to characterization of lipid peroxidation. The second protocol, which relates to linoleic acid-dependent click-chemistry, still does not represent a lipid peroxidation assay. Among these three approaches, the LiperFluo technique is the most closely connected with the mechanisms of ferroptosis dependent on GPX4. Indeed, the fluorogenic response from the probe emerges as a result of reduction of lipid hydroperoxides by a tri-phenylphosphine moiety of the probe in a way similar to GPX4 (Fig. 4) (Kagan et al., 2017). Thus, the fluorescence response detects lipid hydroperoxides. The deficiency of this protocol, however, is that it does not discriminate between many types of lipid hydroperoxides—PUFA-OOH, phospholipid-OOH (PL-OOH), cholesterol-OOH. Most notably, in ferroptosis-resistant Acsl4-deficient Pfa1 fibroblasts, the LiperFluo response was higher than in the ferroptosis-prone WT cells (Kagan et al., 2017).

Fig. 4. Most commonly used assays for indirect assessments of different “peroxidation/peroxidase activities associated with the execution of ferroptosis. Note that only Liperfluo assay detects hydroperoxyl-lipids.

i) BODIPY® 581/591 detects “peroxidase activity” resulting in changed fluorescence characteristics of the non-lipidic BODIPY chromophore. Oxidation of butadiene portion (circled in red) of the BODIPY® 581/591 results in a shift of fluorescence emission peak from 590 nm to 510 nm.

ii) linoleate-based Click-iT® LAA (linoleamide alkyne) assay. This assay is designed to detect lipid-peroxidation derived modification of protein in fixed cells. Incorporated into cellular membranes Click-iT® LAA can undergo lipid peroxidation resulting in production of 9- and 13-hydroperoxy linoleic acid that further decomposes to unsaturated aldehydes which can modify proteins. These modified proteins are detected by Click-iT® chemistry.

iii) Liperfluo fluorogenic assay of hydroperoxy-containing groups. Liperfluo, a perylene derivative containing oligooxyethylene, detects L-OOH. LiperFluo can react with L-OOH and its fluorescence reliably reports intracellular sites of L-OOH accumulation by a fluorescence microscopy. Both free PUFA-OOH and PUFA-OOH esterified into phospholipids display high reactivity toward LiperFluo. The results in the robust fluorescence response of oxidatively modified LiperFluo in cells exposed to pro-ferroptotic stimuli) are shown on the right panel. Chemically, Liperfluo reduces L-OOH to the respective alcohols similarly to the reaction catalyzed by GPX4.

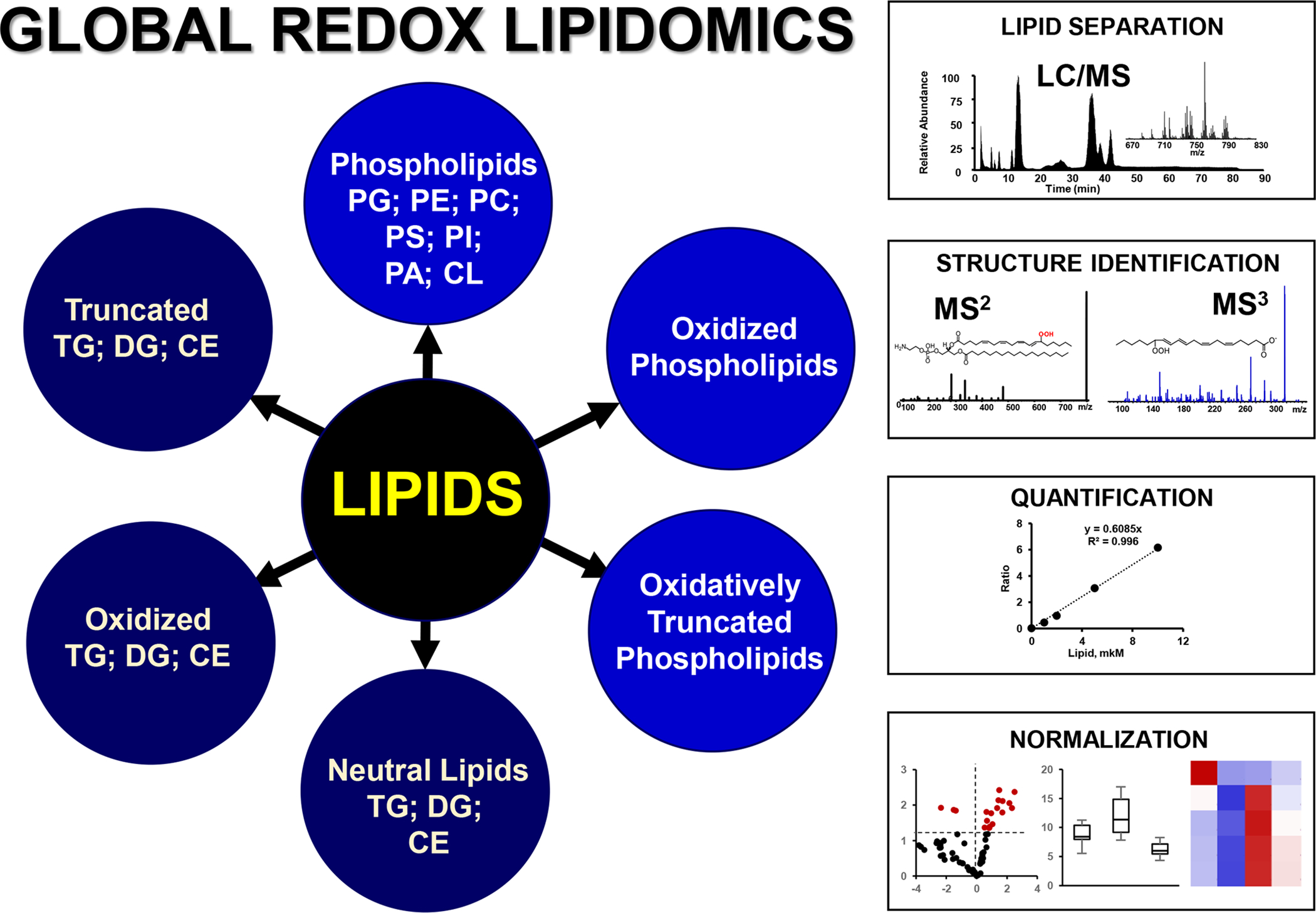

Given the huge diversity of (phospho)lipid peroxidation products detectable by Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) protocols in control cells and tissues, and the enhanced lipid peroxidation response upon triggering ferroptotic death, it is becoming increasingly clear that high resolution LC-MS currently represents the only adequate platform for identification and quantification of ferroptosis-associated lipid peroxidation. Studies of this kind can help in resolving one of the major conundrums of ferroptosis: enzymatic or non-enzymatic free radical lipid peroxidation process. Fig. 5 demonstrates a typical schema of global redox lipidomics analysis of oxygenated lipids and products of their oxidative truncation including major classes of phospholipids and neutral lipids.

Fig. 5. A schema explaining the major stages of LC-MS based non-targeted Global (Redox) Lipidomics Analysis (GRLA).

GRLA includes analysis of phospholipids and neutral lipids including their oxidized and oxidatively truncated species and consists of several steps. The first step is separation of lipids by liquid chromatography and their detection by mass spectrometry. Normal and reverse phase chromatographic protocols are used for separation of lipids based on their polarity and hydrophobicity. Electrospray ionization (ESI) is widely used for the detection of lipids and their oxidatively modified species. Second step is the identification of lipids and their oxidation products. This is achieved by using ion trap or high resolution mass spectrometry (MS) orbitrap instrumentations with unlimited fragmentation capacity. Step three includes quantitative analysis and normalization of results. LC-MS and LC-MS/MS can be set up for quantitative analysis using internal standards and calibration curves established with reference standards.

The high resolution of LC-MS/MS analysis yielding detailed information about the lipid oxidation products and numerous signals is also its “curse”: which of these products are predictive biomarkers of ferroptosis? Answering this question usually relies on the comparative analysis of cells exposed to pro-ferroptotic stimulation (e.g., by a GPX4 inhibitor, RSL3, or system XC− inhibitor, erastin) in the presence and absence of a typical inhibitor of ferroptosis (e.g. Fer-1). The signals from oxidized lipids disappearing/decreasing upon treatment with Fer-1 represent predictive biomarkers of ferroptosis.

Enzymatic vs non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation: the role of LOXs, PEBP1, selectivity/specificity, and adduct formation.

The general reaction schemas of enzymatic and non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation are similar as they include the catalytic abstraction of a bis-allylic hydrogen from the oxidizable substrate molecule (Fig. 3). For non-enzymatic peroxidation of PUFA, the reaction rates are proportional to the number of methylene-interrupted double bonds (i.e. the number of bis-allylic hydrogens) (Yin et al., 2011). Therefore, hexaenoyl- and pentaenoyl-phospholipids should be preferred oxidation substrates with relatively low selectivity with regards to the nature of the polar head of the phospholipids (Yin et al., 2011). Further, the non-enzymatic mechanism should not lead to positional specificity of the oxidation products in the PUFA residue. In contrast to this random profile of free radical peroxidation, enzymatic lipid peroxidation by di-oxygenases (e.g. cyclooxygenases [COXs] and LOXs) is highly substrate-selective and product-specific due to strictly coordinated juxtapositioning of the PUFA residues at the catalytic site (Kuhn et al., 2015). These substantial differences suggest that LC-MS/MS characterization of the reaction substrates and products may be diagnostic in establishing the enzymatic vs non-enzymatic nature of the peroxidation process.

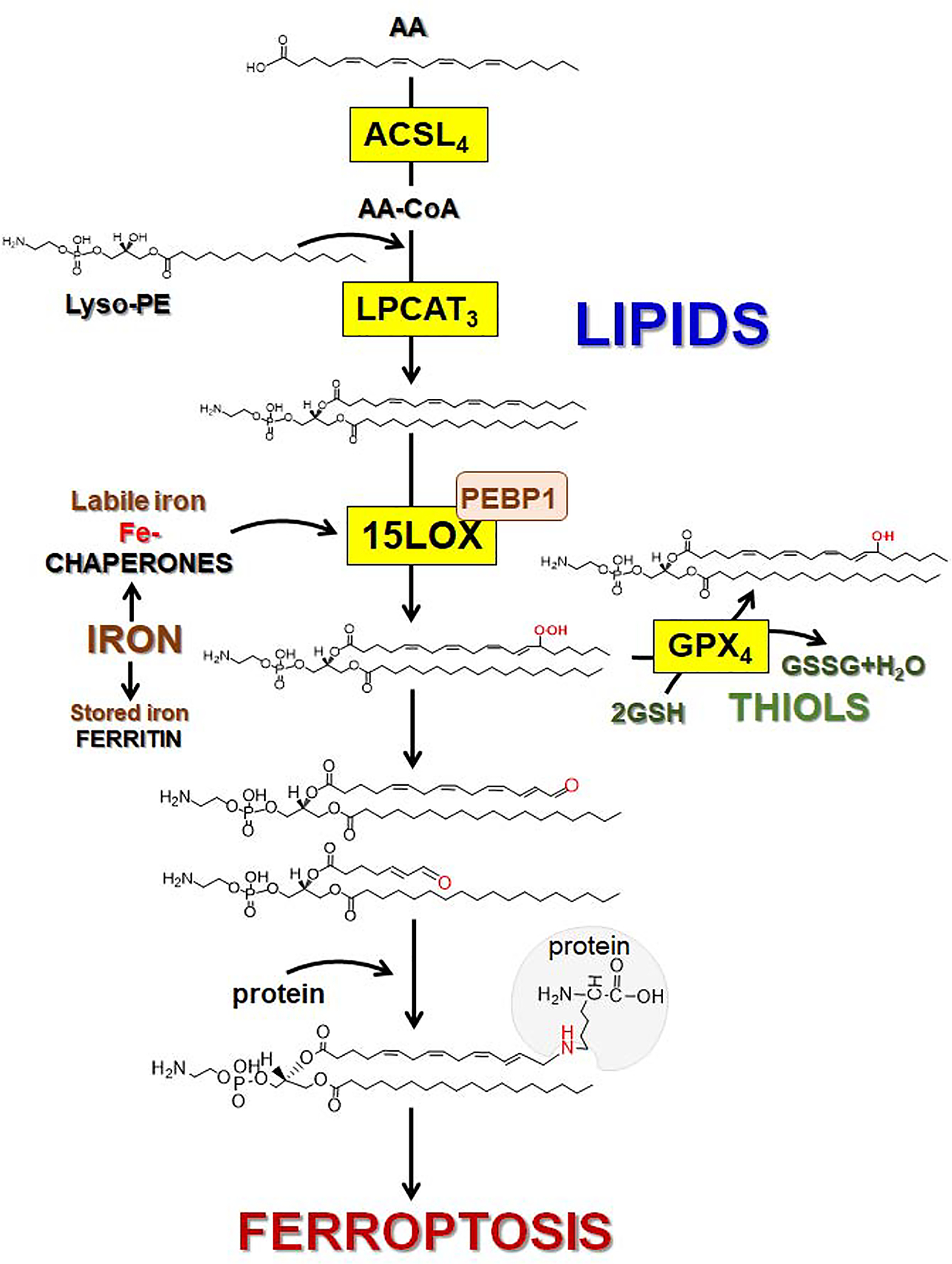

This background information may be useful for the critical analysis of the known facts related to ferroptotic lipid peroxidation (Fig. 67). Very early studies established the essentiality of Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) for the effective execution of ferroptosis (Doll et al., 2017; Kagan et al., 2017). Given that these two proteins are necessary for the activation of PUFA, particularly AA, to yield CoA-forms utilized for the esterification of free PUFA and re-acylation of lyso-phospholipids, respectively, it has been concluded that PUFA-phospholipids, rather than free PUFA were utilized as peroxidation substrates (Kagan et al., 2017). Subsequent LC-MS/MS work indicated that AA-PE are the preferred peroxidation substrates and HOO-AA-PE are the most common products (Kagan et al., 2017).

With regards to the positional specificity, there is evidence, albeit less unequivocal, that 15-HOO-AA-PE is the likely oxidation product (Anthonymuthu et al., 2018). The fact that COXs oxidize free rather than esterified peroxidized PUFA has led to the conclusion that LOXs may be the likely candidate enzymatic catalysts of ferroptotic peroxidation (Kagan et al., 2017). Of several mammalian LOXs, two isoforms of 15-LOX are known to be capable of attacking and peroxidizing membrane phospholipids (Chaitidis et al., 1998). This chain of logic put forward 15-LOX as the catalytic mechanism of ferroptotic AA-PE peroxidation (Kagan et al., 2017). While this conclusion was in line with the initial work on the involvement of LOXs in non-apoptotic cell death (Seiler et al., 2008a), subsequent studies with genetic deletion of different LOXs produced less definitive results (Friedmann Angeli et al., 2014a), still implicating some LOX isoforms in the ferroptotic peroxidation (Friedmann Angeli et al., 2014a). These studies might also be indicative of the requirement of additional regulatory factors controlling the phospholipid peroxidation process. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that the formation of the complex of 15-LOX with a scaffold protein, PEBP1, was required for the effective generation of pro-ferroptotic 15-HOO-AA-PE in several types of mammalian cells and tissues in normal and disease conditions (e.g. brain trauma, asthma, acute kidney injury) (Wenzel et al., 2017). Further analysis also demonstrated that the 15-LOX/PEBP1 complex, rather than 15-LOX alone, was important for the selective and specific peroxidation of AA-PE and the formation of 15-HOO-AAPE. LC-MS/MS analysis confirmed this remarkable catalytic selectivity and specificity of the 15-LOX/PEBP1 complex (Anthonymuthu et al., 2018) (Fig. 6) and demonstrated that AA-PE—out of hundreds of molecular species of alternative oxidizable PUFA-phospholipids—was the predominantly peroxidized phospholipid. Furthermore, even among dozens of oxidizable PUFA-PE-species, AA-PE was identified as the preferred peroxidation substrate and oxidized AA-PE as the peroxidation product (Fig. 6). While the initial studies (Kagan et al., 2017) indicated that the major locations of the generators of HOO-AA-PE are predominantly associated with ER sites, further studies are necessary to explore the involvement of AA-PE pools of mitochondriaassociated membranes and mitochondria.

Fig. 6. Schematic representation of the major stages of lipid redox metabolism leading to the formation of HOO-AA-PE as a pro-ferroptotic signal.

Esterification of arachidonic acid (AA) into phosphataidylethanolamine (PE) requires acyl-CoA synthase 4 (ACSL4) catalyzed formation of AA-CoA which is used for the AA esterification into lyso-PE driven by lysophosphatidyl-choline acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) to yield AA-PE. Assembly and engagement of 15-LOX/PEBP1 enzymatic complexes changes 15-LOX substrate selectivity from AA to AA-PE thus facilitating the generation of specific product (15-HOO-AA-PE). Under ferroptotic conditions, the activity of GPX4 is inhibited, thus HOO-AA-PE cannot be reduced to HO-AA-PE. In contrast oxidatively-truncated electrophilic products of HOO-AA-PE with shortened side chains and electrophilic oxygen functionalities are formed. These oxidatively-truncated PE products form adducts by attacking nucleophilic sites in target proteins thus leading to the yet to be identified gateway ferroptotic complexes.

Interestingly, the 15-LOX gene and its protein product, pLoxA have also been found in a prokaryotic organism, a pathogenic Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which does not contain its own PUFA peroxidation substrates but uses the protein for the pro-ferroptotic attack of the host AA-PE phospholipids (Fig. S2) (Dar et al., 2018). This work not only confirmed that the 15-LOX-driven PE-peroxidation represents an evolutionary conserved and ancient effective mechanism of cell death, but it also confirmed the sufficiency of 15-LOX as a mechanism of ferroptotic death (Dar et al., 2018). Assuming that 15-LOX/PEBP1 is an important catalyst of pro-ferroptotic phospholipid peroxidation, further attempts have been made to explore the possible mechanisms of its regulation, possibly duplicating the central anti-ferroptotic role of GPX4. Several regulatory mechanisms targeting different stages of the process leading to the generation and accumulation of the pro-ferroptotic signals have been identified. One of them is based on the iNOS/NO•-driven suppression of 15-LOX/PEBP1 catalytic activity preventing the formation of the death signal (Kapralov et al., 2019). Interestingly, this regulatory mechanism may act independently of the GPX4/GSH system. Another regulatory system, acting independently of the canonical thiol-driven pathway, includes the ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) that blocks and/or attenuates the production of ferroptotic signals via controlling the reduction of a non-mitochondrial CoQ (Bersuker et al., 2019; Doll et al., 2019). Upon recruitment of FSP1 to the plasma membrane, its oxidoreductase activity reduces CoQ and suppresses the accumulation of L-OOH.

In spite of this significant support for the enzymatic mechanism of the production of the pro-ferroptotic death signal, there are two groups of facts contending the enzymatic nature of lipid peroxidation: i) high effectiveness of a number of free radical scavengers of different nature—aromatic amines, phenolic compounds, thiols—in preventing/suppressing ferroptosis and ii) the lack of correlation between the high anti-ferroptotic activity and the ability to inhibit LOXs. These important arguments deserve further focused research attention and necessitate testing of these compounds as regulators not only of LOX alone but also of 15-LOX/PEBP1 complexes. Such studies have not been reported so far. Their meaningfulness, however, should be considered in view of the possible design of highly specific anti-ferroptotic remedies suppressing the activity of 15-LOX/PEBP1 complexes without affecting the physiologically important reactions by LOXs catalyzing the production of numerous lipid mediators.

While the enzymatic nature of the HOO-AA-PE production seems highly likely, there is yet another possibility for the essential participation of free radical scavengers in the regulation of ferroptosis. This relates to the poorly explored second stage of the lipid peroxidation process and formation of the oxidatively truncated electrophilic species that interact with nucleophilic sites of yet to be identified proteins and may serve as the proximate executioners of ferroptosis. This difficult task may be significantly simplified assuming that these secondary products are generated from a limited number of PL-OOH.

Clearly definitive decoding of the mechanism of lipid peroxidation—enzymatic vs nonenzymatic—is not only an academic matter as a considerable number of injuries and disease conditions include ferroptotic cell death as one of the important pathogenic mechanisms. Hence, therapeutic and prevention strategies should rely on strong and unequivocal evidence.

Prerequisites and specific features of pro-ferroptotic lipid peroxidation in the brain.

The content of PUFA glycerophospholipids, particularly AA (C20:4)- and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6)-phospholipids, is high (~60%) in the brain (Chen et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018a). Among all phospholipids, PE (18:0/20:4) and PE (18:0/22:6) are the most abundant species (Choi et al., 2018). Given that AA-PE is essential for the production of ferroptotic death signals, this means that AA-PE is readily available and does not represent the limiting factor for the 15-LOX/PEBP1 catalyzed generation of HOO-AA-PE. Within the brain tissue, the amount of PUFA containing phospholipids differs depending on the cell type and developmental stage. For example astrocytes have relatively lower content of PUFA containing phosholipids vs. neurons, and premature brain has less PUFA containing phospholipids vs. adult brain (Martinez and Mougan, 1998; Tyurina et al., 2014). Thus, it is possible that ferroptosis sensitivity could depend on age and cell type even if the ferroptotic insult is similar in magnitude. However, this does not take into consideration the other key components of the ferroptotic program: 15-LOX and GSH. Notably, contemporary MS imaging, particularly the protocol of secondary ion MS utilizing gas cluster ion beams (Tian et al., 2019), detects AA-PE species in different subcellular localizations of brain cells (e.g. neurons, astrocytes) (Fig. S3), thus offering remarkable opportunities for identifying the major sites of catalytic initiation of the ferroptotic process.

While most LOXs usually oxygenate free PUFA, some of isoforms (e.g. 15-LOX) can directly attack PUFA (including AA) esterified into phospholipids, particularly PE. Canonically, the AA released from phospholipids in phospholipase A2-driven reactions is metabolized by COXs or LOXs to form lipid mediators (Mouchlis and Dennis, 2019; Shearer and Walker, 2018). Among the three forms of LOXs (5-LOX, 12-LOX, and 15-LOX) in the brain, 5-LOX is localized in the cytosol in neuronal cells and involved in generation of 5-HOO-AA, 5-HOO-AdA, and pro-inflammatory lipid mediators, leukotriens (Radmark et al., 2015). 12-LOX catalyzes oxygenation of AA to generate 12-HpETE and 12-HOO-AA (Li et al., 1997a). 15-LOX is the predominant isoform in the mammalian brain (Shalini et al., 2018). Normally, the level of the enzyme is low, but its expression increases many-fold in an array of diverse pathologies, including in response to acute brain injury (Kagan et al., 2017; Tyurina et al., 2019; Wenzel et al., 2017). 15-LOX can utilize AA and DHA as its substrates to generate anti-inflammatory lipid mediators, including AA-derived lipoxin A4 and DHA-derived resolvins (RvD1, RvD5) and neuroprotectins (Protectin D1) (Dalli et al., 2013; Green et al., 2018; Shalini et al., 2018). In addition, esterified oxygenated PUFA can act as signals for triggering different death pathways in cells (Kagan et al., 2017; Kagan et al., 2005) and elimination of dead cells (Tyurin et al., 2014). Importantly, 15-LOX is implicated in the generation of HOO-AA and HOO-AdA molecular species of PE recognized as ferroptotic cell death signals (Kagan et al., 2017; Wenzel et al., 2017). PEBP1 is abundantly expressed in the brain (Burgula et al., 2010) (Wang et al., 2017) specifically in neurons (Hellmann et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2019), and its role and contribution to different types of neuronal injury are subjects of active investigation (Jung et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019). Recent studies established that 15-LOX/PEBP1 complexes are engaged in the mechanisms of ferroptotic neuronal death after traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Kenny et al., 2019; Stockwell et al., 2017; Wenzel et al., 2017).

GSH AND GPX4 IN FERROPTOSIS

Ferroptosis was originally described as a non-apoptotic form of cell death induced by the inhibition of cystine transportation by system XC− that can be rescued by Fer-1 or by iron chelators, such as deferoxamine (Dixon et al., 2012a). Since then, perturbations of GSH and GPX4, either through depletion of GSH or by inhibition of GPX4 activity, have been used as the major ferroptosis inducing method (Dixon and Stockwell, 2019). Although cell death caused by inhibition of GSH synthesis (Zaman et al., 1999) and GPX4 inactivation (Seiler et al., 2008b) has been known long before, the relationships between GSH, GPX4, iron, and lipid peroxidation have been clearly conceptualized in the context of ferroptosis.

GSH Synthesis

The thiol-containing tripeptide GSH (γ-L-glutamyl-L-cysteinylglycine) is the major component of the cellular antioxidant defense system against oxidative stress including lipid hydroperoxides (Meister and Anderson, 1983). GSH is the most abundant small molecule antioxidant present in cells. The concentration of GSH can vary in different cell types with the highest level reaching up to 12 mM in liver cells (Cooper, 1997). GSH is synthesized from its constituent amino acids—glutamic acid, cysteine, and glycine—through a two-step pathway. The initial step is the joining of glutamate and cysteine to produce the dipeptide γ-GluCys. Subsequently, γ-GluCys is combined with glycine to produce GSH. The first and rate-limiting step of GSH synthesis is catalyzed by glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL, previously called glutamylcysteine synthetase). Mechanistically, the gamma-carboxyl group of the amino acid L-Glu is activated by ATP-assisted phosphorylation followed by the reaction with an amino group of L-Cys (Meister, 1974). GCL is a dimeric protein comprised of a heavy, catalytic subunit and a light, modifier subunit, each of which is encoded by separate genes. Synthesis of GSH is precisely regulated by alteration of GCL activity through feedback inhibition by GSH, availability of L-Cys, and transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation (Hibi et al., 2004). Buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) is a classical GCL inhibitor shown to induce ferroptosis (Griffith, 1982; Nishizawa et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2014a). Conversion of γ-GluCys to GSH is catalyzed by glutathione synthetase (GS). GS is comprised of two subunits and like GCL, uses ATP as a co-substrate (Oppenheimer et al., 1979). Though GS is not the rate-limiting enzyme during normal GSH synthesis, it could play a decisive role during GSH synthesis especially during pathological conditions (Lu, 2009a). Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a transcriptional regulator of both the GLC and GS shown to be involved in the execution of ferroptosis (Abdalkader et al., 2018).

System XC−

GSH synthesis is limited by the availability of one of its constituting amino acids, L-Cys (Shih et al., 2006). Cysteine is normally derived from two pathways: i) transmethylation and transsulfuration of the essential amino acid methionine (Tarver and Schmtdt, 1939) and ii) reduction of cellular cystine. Normally, cysteine is transported as its oxidized dimer, cystine, at the extracellular space (Kranich et al., 1998) (Bannai and Tateishi, 1986). Cystine is imported into the cells via an exchange for glutamic acid through system XC−, a cystine-glutamate exchanger. System XC− is a member of the heteromeric amino acid transporter (HAT) family, which consists of heterodimers of solute carrier 3 (SLC3) and solute carrier 7 (SLC7) family proteins (Broer and Wagner, 2002). Likewise, system XC− is composed of SLC3A2 (4F2hc, heavy chain) and SLC7A11 (xCT). The heavy chain is responsible for the amino acid transport while the xCT unit is required for anchoring the complex at the cell surface. Once transported, cystine is immediately converted into cysteine by the intracellular GSH pool or through thioredoxin reductase (Mandal et al., 2010). Because of instantaneous depletion of intracellular cystine combined with the high cellular glutamate concentration, system XC− predominantly acts as cystine importer and glutamate exporter (Bannai, 1986). Extracellular glutamate is a competitive inhibitor of cellular cystine uptake (Makowske and Christensen, 1982). System XC− is constitutively expressed; however, its activity can be regulated at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels (Lewerenz et al., 2012). System XC− is the most extensively studied axis in ferroptosis execution, and multiple system XC− inhibitors such as erastin, imidazole-keto-erastin, sulfasalazine, and glutamate have been shown to activate ferroptosis (Stockwell et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019b). Mechanistically erastin and sulfasalazine promote the phosphorylation of BECN1 through AMPKα and subsequent formation of the BECN1-SLC7A11 complex, which inhibits the cystine uptake (Song et al., 2018). System XC− regulates two important molecules implicated in neuronal cell death, extracellular glutamate and intracellular GSH. Extracellular glutamate can also overactivate ionotropic glutamate receptors such as α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), KA, and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) types (Lodge, 2009; Soria et al., 2014), leading to excitoxic neuronal death (Sheldon and Robinson, 2007). This makes system XC− one of the major therapeutic targets in neuronal disorders. Expression of system XC− is also regulated by the transcription factor Nrf2, making Nrf2 the major transcriptional regulator in modulating GSH levels (Harvey et al., 2009). Mice with deleted system XC− are fully viable, suggesting alternative pathways in GSH synthesis. However, the development of ferroptosis in such a system has not yet been studied (Sato et al., 2005).

Role of mitochondria in GSH synthesis.

The synthesis of GSH occurs exclusively in the cytosol of the cells with subsequent distribution to subcellular organelles (Griffith and Meister, 1985). Since mitochondria are responsible for the majority of ROS production in cells, a significant amount of GSH is transported into the mitochondria. Two inner mitochondrial membrane anion transporters, the dicarboxylate carrier (DIC, Slc25a10) and the 2-oxoglutarate carrier (OGC, Slc25a11) transport GSH into the mitochondria (Azzi et al., 1967; Lash, 2006; Meijer et al., 1972). Mitochondria receive 10–15 % of the total cellular GSH that equalizes the mitochondrial GSH concentration to the cytosolic GSH concentration (Griffith and Meister, 1985). In turn, mitochondria play a vital role in the synthesis and regulation of GSH. More specifically, the availability of glutamate is tightly controlled by mitochondrial metabolism. Three of the major glutamic acid metabolic enzymes, glutaminase (GLS), glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), and aspartate aminotransferase, are housed in the mitochondria (Newsholme et al., 2005). GLS converts glutamine into glutamate through a deamination reaction. Mitochondrial glutamate is converted into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle cycle intermediate alpha-ketoglutarate (α-KG) either by glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) or by the alanine or aspartate transaminases (TAs) (Watford, 2000). Both GDH and TAs are considered as cataplerotic enzymes forming products necessary for removing TCA cycle intermediates (Owen et al., 2002). These pathways are involved in the precise regulation of glutamate in the cytosol which in turn regulates the cystine intake by system XC− and subsequent GSH synthesis (Lu, 2000).

Function and metabolism of GSH.

Cellular GSH is required for several vital functions such as: 1) modulating cellular processes such as protein s-glutathionylation (Dalle-Donne et al., 2009), DNA synthesis (Suthanthiran et al., 1990), and immune response (Furukawa et al., 1987), 2) supplying cysteine for protein synthesis (Meister and Anderson, 1983), 3) metal ion homeostasis (Jozefczak et al., 2012), 4) maintaining the redox status of the proteins, and 5) providing an antioxidant defense (Lu, 2009b). GSH is also a critical component used to assemble iron-sulfur clusters in the cytosol and the mitochondria. Assembling Fe-S clusters is a vital function of mitochondria. Furthermore, GSH is the major small molecule that coordinates iron in the cytosol and is necessary for its coordination by iron chaperones (Patel, et al, 2019). The antioxidant capacity of GSH is useful in detoxifying xenobiotics and in the removal of ROS (Forman et al., 2009). Removal of ROS by GSH is achieved by non-enzymatic and enzymatic ways. In the non-enzymatic process, GSH reacts with hydroxyl radical, nitric oxide, and superoxide radicals (Dringen, 2000). However, this reaction generates a strong pro-oxidant thiyl radical. Hence, the protective non-enzymatic role of GSH as a radical scavenger may not be commonly realized in biological systems (Sagristá et al., 2002; Sturgeon et al., 1998).

GSH is an obligatory co-substrate of the non-heme enzymes, GPXs, which are involved in the reduction of peroxides to water or corresponding alcohols. Eight families of human GPXs have been identified (Brigelius-Flohé and Maiorino, 2013). GPX1–4 and 6 are selenoenzymes containing a selenocysteine at the catalytic center, whereas GPX5, 7, and 8 contain cysteine instead of selenocysteine. Hydrogen peroxide is the major oxidizing substrate for GPX1, 3, 7, and 8. Small molecular organic hydroperoxides including soluble free fatty acid peroxides are also reduced by GPX1 and 3. GPX4 is involved in reducing peroxides at the cellular membranes e.g. hydroperoxides of fatty acid residues in phospholipid peroxides and cholesterol hydroperoxides (Brigelius-Flohé and Maiorino, 2013). During the reduction of peroxides, GSH is converted into its oxidized dimeric form, GSSG, which can be recycled back into GSH using electrons transferred from reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate by glutathione reductase (GR) (Carlberg and Mannervik, 1985). Thus, the availability of reduced GSH is regulated by NAD(P)H supply. The major metabolic pathways contributing to NAD(P)H production are glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphoglucanate dehydrogenase, enzymes of pentose-phosphate pathway (PPP) (Lunt and Vander Heiden, 2011; Xiao et al., 2018; Yang and Sauve, 2016). Besides PPP, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase of glycolysis (Lunt and Vander Heiden, 2011), isocitrate dehydrogenase, and malate dehydrogenase (Lunt and Vander Heiden, 2011; Yang and Vousden, 2016) of TCA cycle are the enzymes involved in the synthesis of NADPH. The levels of GSH/GSSG are closely associated with NADPH/NADP+ concentration. Numerous studies have shown involvement of metabolism in the regulation of ferroptosis. Inhibition of PPP enzymes ameliorate resistance to ferroptosis induced by erastin (Dixon et al., 2012a). Blockage of glycolysis by 2-deoxy-d-glucose substantially inhibits lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, reportedly via AMPK pathway (Lee et al., 2020). Cellular GSH is also controlled by thioredoxin superfamily proteins such as thioredoxins, peroxiredoxins, and glutaredoxins (Xiao and Loscalzo, 2019). A high content of thioredoxin superfamily proteins is characteristic of cells of the central nervous system (Aon-Bertolino et al., 2011; Silva-Adaya et al., 2014), and different redoxins provide proper redox-regulations during neuronal differentiation and maturation processes (Olguín-Albuerne and Morán, 2018). Specifically, peroxiredoxin 6, one of the six peroxiredoxins which is involved in reduction of phospholipid hydroperoxides to phospholipid alcohols is protective in non-neuronal cells against ferroptosis (Lu et al., 2019)

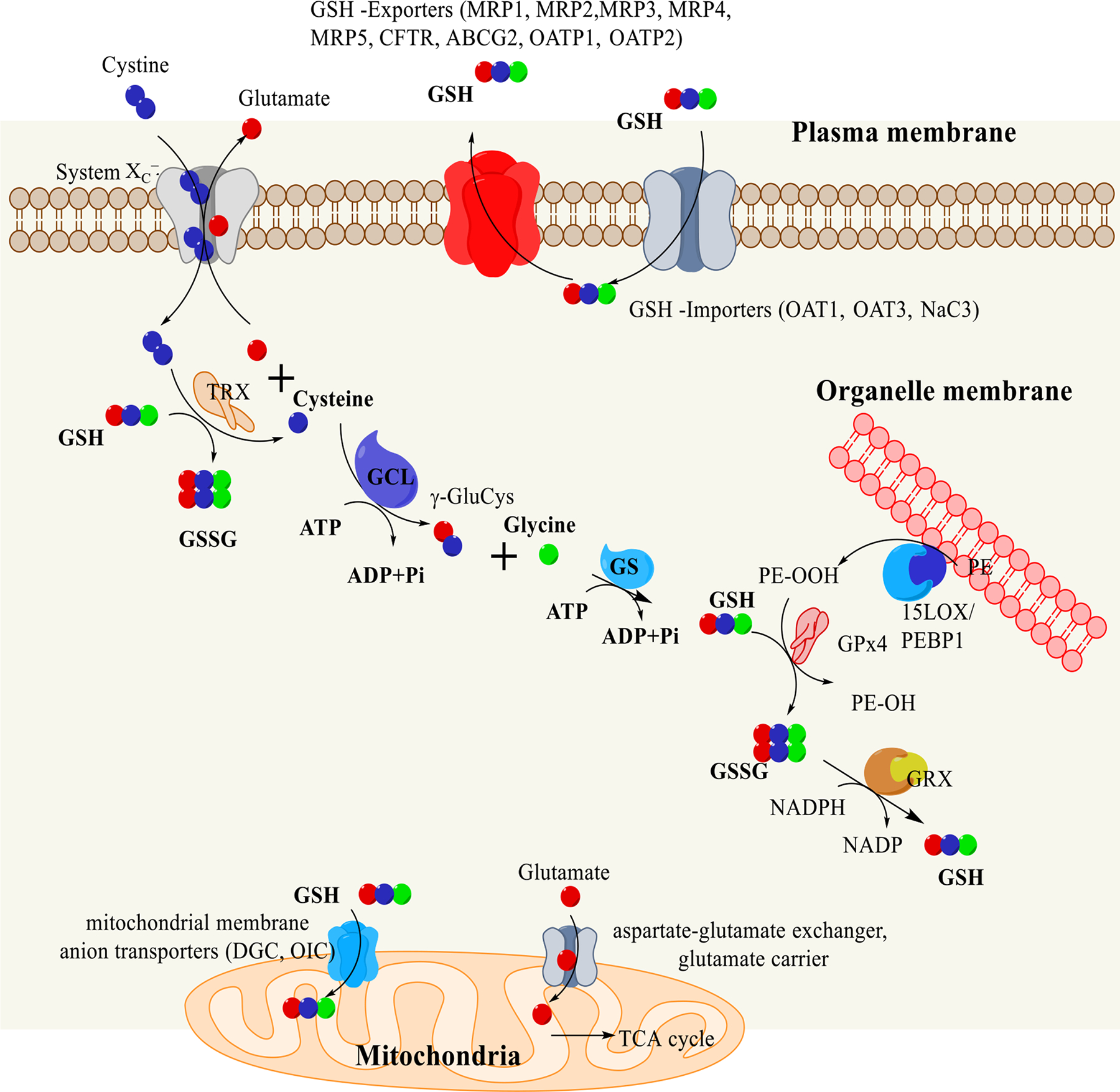

While much of the GSH is utilized inside the cell, GSH is also transported across the plasma membrane for maintaining extracellular and inter-organ GSH homeostasis. Seven ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABC) family proteins—multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) 1–5, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily G Member 2, and two organic-anion-transporting polypeptide (OATP) family members (OATP1, OATP2)—are involved in the export of cellular GSH (Fig. 7). Three solute carrier proteins, OAT1, OAT3, and Na+/Ca2+-Exchange Protein 3 (NaC3), are shown to be involved in the import of GSH to the cytoplasm (Bachhawat et al., 2013).

Figure 7.

Metabolism of GSH. Cystine is imported into the cells with an expense of glutamate by system Xc-. Glutamate levels in the cytoplasm dictates the cystine transport. Cytosolic glutamate level is controlled by its transport to mitochondria through two transporters aspartate glutamate exchanger and glutamate carrier. Mitochondrial glutamate is used in the TCA cycle after its conversion to α-ketoglutarate. Transported cystine is converted to cysteine by thioredoxin (TRX) or by GSH. Cysteine is then converted to γ-glutamylcysteine (γ-GluCys) by glutamate cysteine ligase (GCS). GSH is synthesized by the addition of a glycine group to γ-GluCys by glutathione synthetase (GS). 10–15% of the GSH are transported to the mitochondria by dicarboxylate carrier (DIC) and the 2-oxoglutarate carrier (OGC). GSH is also transported across various transporters. PE-OOH produced from the organelle membrane is reduced to PE-OH by glutathione peroxidase4 (GPX4) using GSH. During the reduction process of PE-OOH to PE-OH, GSH is oxidized to GSSG, which are then converted into GSH by glutathione reductase (GRX).

GPX4

Among various GPXs, only GPX4 is known to reduce phospholipid hydroperoxides (Thomas et al., 1990; Ursini et al., 1982). GPX4 exists in 4 different isoforms, 3 of which have their specific subcellular locations: cytosolic GPX4, mitochondrial GPX4, and nuclear GPX4. A DHA-inducible splice variant of GPX4 identified in murine hippocampal HT22 cells is the fourth isoform of GPX4. Cytosolic GPX4 is the ubiquitously expressed predominant form of GPX4. Mitochondrial GPX4 is essential for survival and apoptotic resistance (Liang et al., 2009). GPX4 is a monomeric N-glycosylated protein (Wang et al., 2013) containing four α-helixes and 7 β-strands that form a thioredoxin motif (Scheerer et al., 2007). Like other GPXs, GPX4 follows a two-stage ping-pong mechanism to reduce peroxide. The first step involves the reduction of the PL-OOH to an alcohol with spontaneous oxidation of selenium. This step changes the position of GPX4 on the membrane making the selenium oxide accessible to the soluble GSH. Subsequently, selenium oxide is reduced by GSH in the second step (Brigelius-Flohé and Maiorino, 2013) forming GSSG and active GPX4 (Cozza et al., 2017).

GPX4 is a unique component of the essential antioxidant enzymes responsible for maintaining redox homeostasis in the cells. As a result, embryonic inactivation of GPX4 is lethal in mice (Ingold et al., 2015). However, adult mice with conditional GPX4 knockout die from acute renal injury (Friedmann Angeli et al., 2014c; Imai and Nakagawa, 2003; Yant et al., 2003). GPX4 is ubiquitously expressed in the human body, albeit with varying expression levels. Testis has the highest level of GPX4 expression, while brain has a low to moderate GPX4 expression. However, GPX4 is one of the most abundant constitutively expressed selenoproteins in the brain (Pitts et al., 2014). Depletion of neuronal GPX4 is lethal that can be prevented by either by α-tocopherol, 12/15-LOX inhibitors, or siRNA-mediated apoptosis-inducing factor silencing (Seiler et al., 2008b). GPX4 is one of the major regulators in the execution of ferroptosis.

THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES TARGETING INHIBITION OF FERROPTOSIS IN NEURONAL DISEASES

As the execution of ferroptosis engages three major metabolic redox pathways, it may be subject to multi-faceted regulation. This multiplicity of possible targets also represents a practical difficulty: which of the participating processes should be targeted? Another dilemma is that there are many already known inhibitors of ferroptosis—do we need to seek out new ones? The involvement of the multiple important pathways is a blessing because of the many choices of targets it offers, but it is also a curse because many essential pathways may be affected thus causing undesirable side effects. Using inhibitors which limit the availability and delivery of iron to its protein clients might lead to multiple manifestations of iron insufficiency. Iron is an essential cellular nutrient that is involved in vital cellular activities, such as oxygen transport, energy metabolism, and DNA synthesis (Lu, 2000). In fact, iron deficiency-related anemia is one of the major global health problems (Camaschella, 2015). Similarly, targeting the GSH/GPX4 axis of ferroptosis may interfere with numerous essential functions of thiols in regulating the cellular redox homeostasis. While the control of lipid peroxidation may represent the most attractive strategy, this approach may also cause nonspecific side effects. For example, baicalein is an excellent pan-inhibitor of LOX, and its application will likely affect multiple important pathways for biosynthesis of lipid mediators, making the prediction of the outcomes difficult. Even targeting one of the LOXs, 15-LOX, may have multiple consequences and side effects due to the important roles of 15-LOX in several biosynthetic reactions, producing pro- and anti-inflammatory lipid mediators, eicosdanoids and docosanoids (Dennis and Norris, 2015). These considerations lead to the conclusion that selective inhibitors targeting specific pro-ferroptotic reactions of 15-LOX/PEBP1 complexes may be the optimized solution. In the following section, we will present the ideas and data on the possible control and regulation of ferroptotic pathways with regard to the development of new therapeutic approaches.

GSH replenishment.

GSH/GPX4 acts as a negative regulator of ferroptosis; increased levels/activity of GSH/GPX4 suppresses ferroptosis, whereas a decrease in iron and lipid peroxidation is necessary for ferroptotic inhibition. Increasing GSH levels as a therapeutic strategy had already been attempted in many neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases (Cacciatore et al., 2012; Mischley et al., 2016). N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) (Bavarsad Shahripour et al., 2014), liposome encapsulated GSH (Cacciatore et al., 2012), and glutathione esters (Anderson et al., 1985) are some of the compounds used for replenishing GSH levels. Few studies however investigated the effects of GSH replenishment in the context of ferroptosis (Karuppagounder et al., 2018). The cysteine pro-drug, NAC, has attracted attention due to its clinical use as an FDA approved medication for acetaminophen-induced liver injury (Smilkstein et al., 1988). In an elegant study, Ratan and his group showed that hemin (heme oxidation product)-induced ferroptosis in primary neurons can be attenuated by NAC even 12h after the exposure (Karuppagounder et al., 2018). The mechanism of protection was, in a large part, due to increased intracellular GSH levels enabling the GSH utilizing enzyme, GSH-S-transferases, to detoxify 5-LOX-mediated lipid-derived protein oxidation (Karuppagounder et al., 2018). Interestingly while NAC was successful in attenuating collagenase-induced hemorrhagic stroke in mice, it was ineffective in rats due to drug tolerability issues since large doses of NAC (millimolar concentrations) were required to attenuate ferroptosis both in vivo and in vitro (with hemin as the hemorrhagic stroke model in vitro in primary neurons). Thus, translating these studies to humans might be challenging. NAC is known to have poor brain exposure when the blood brain barrier (BBB) is intact (Samuni et al., 2013). This might be less of a problem in disease states such as TBI or hemorrhagic stroke where the BBB is temporarily disrupted. However, even in these situations BBB integrity recovers with time (Kushi et al., 1994; Stevens et al., 1999). NAC’s poor brain exposure is not only due to its low BBB permeability but also active transport of this drug out of CNS via transporters (Hagos et al., 2017; Samuni et al., 2013) A recent phase-I study showed that brain exposure of NAC can be increased in patients when NAC is combined with an inhibitor of the transporters, probenecid (Clark et al., 2017). Probenecid has been shown to prevent active efflux of GSH and its conjugates by inhibiting MRP transporters (Versantvoort et al., 1995). In addition, co-administration of probenecid reduces the clearance of NAC and increases both plasma and brain levels of NAC by inhibiting OAT1- and OAT3-mediated uptake of NAC into renal tubule (Hagos et al., 2017). In line with a synergistic effect of probenecid with NAC, the combination rescues HT22 neuronal cells from glutamate-induced ferroptosis while neither NAC nor probenecid was effective by itself. Expectedly, however, neither NAC nor the combination of NAC and probenecid has a beneficial effect when GPX4 is inhibited by RSL3 (unpublished observations) indicating the critical role that GPX4 plays in neuronal health. If GPX4 is inhibited, the high levels of GSH do not protect the cells from ferroptotic insult.

This brings us to potential strategies of regulating GPX4 function i.e. reducing PL-OOH to corresponding alcohols. Although its effect in ferroptotic death has not been explored, GPX-mimic Ebselen has been shown to ameliorate neuronal injury in both acute and chronic CNS diseases (Maiorino et al., 1992; Schewe, 1995). Another strategy could be augmenting neuronal expression of GPX4 as it was shown by Alim et al., via injection of the AAV8 vector encoding GPX4 under the control of Synapsin 1 promoter into the brain parenchyma (Alim et al., 2019). However, this strategy requires pretreatment prior to CNS insult and would have limited clinical translational potential. GPX4 requires selenium in the form of selenocysteine for its activity (Ingold et al., 2018). While substitution of selenocysteine with cysteine rescues embryonic lethality in GPX4-deficient mice, GABAergic parvalbumin interneurons do not develop in the absence of selenocysteine deficient GPX4 leading to seizures (Ingold et al., 2018), indicating an essential role for selenium in CNS function. In addition to its roles in normal development, pharmacological supplementation of selenium has been shown to improve outcome after acute brain injury (Alim et al., 2019; Reisinger et al., 2009; Savaskan et al., 2003). However, a narrow therapeutic index and the requirement of intracerebroventricular delivery to be effective in CNS insults (Alim et al., 2019) make selenium administration a challenging therapy. Overcoming these shortcomings, a peptide containing selenium, TatSelPep, was recently shown to be effective in attenuating neurological dysfunction after hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke in mice (Alim et al., 2019). The mechanism was found to be transcriptional upregulation of GPX4 and inhibition of ferroptosis as well as excitotoxic and endoplasmic stress-mediated cell death.

GPX4 deficiency leads to early embryonic lethality (Friedmann Angeli et al., 2014b), which can be prevented by a vitamin E enriched diet containing α-tocopheryl acetate (Carlson et al., 2016). Conditional ablation of GPX4 in neurons results in rapid motor neuron degeneration due to ferroptosis and paralysis in adult mice. Supplementation with vitamin-E delayed the onset of paralysis and death induced by GPX4 ablation (Chen et al., 2015). Conversely, when mice with conditional deletion of GPX4 in forebrain neurons were fed a diet deficient in Vitamin E, hippocampal neurodegeneration and deficits in spatial learning and memory were accelerated (Hambright et al., 2017). These studies point to the important role of vitamin-E in the detoxification of lipid peroxyl radicals. During this process, the resultant tocopherol radical is reduced back to tocopherol by ascorbic acid and dihydrolipoic acid via the vitamin E recycling process (Kagan et al., 1992). Vitamin E derivatives—tocopherol and to a greater extent tocotrienols—are known to inhibit LOX activity (Khanna et al., 2003). The mechanism of inhibition is likely via specific liganding of the LOX catalytic site outcompeting binding and oxygenation of free or PE-esterified AA and AdA (Kagan et al., 2017). An endogenous metabolite of vitamin E, α-tocopherol hydroquinone inhibits ferroptosis via reducing active Fe(III) to an inactive Fe(II) at the active site of 15-LOX (Hinman et al., 2018). There have been numerous experimental and clinical studies evaluating the potential beneficial effects of vitaminE for prophylaxis or treatment of both acute and chronic CNS disorders (Anthonymuthu et al., 2016; Lee and Ulatowski, 2019). Although most studies evaluated tocopherols in this respect, the neuroprotective potential of tocotrienols may be greater than tocopherols (Patel et al., 2011).