Abstract

Tumors caused by loss-of-function mutations in genes encoding TCA cycle enzymes have been recently discovered and are now of great interest. Mutations in succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunits cause pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (PCPG) and syndromically associated tumors, which differ phenotypically and clinically from more common SDH-intact tumors of the same types. Consequences of SDH deficiency include rewired metabolism, pseudohypoxic signaling and altered redox balance. PCPG with SDHB mutations are particularly aggressive, and development of treatments has been hampered by lack of valid experimental models. Attempts to develop mouse models have been unsuccessful. Using a new strategy, we developed a xenograft and cell line model of SDH-deficient pheochromocytoma from rats with a heterozygous germline Sdhb mutation. The genome, transcriptome and metabolome of this model, called RS0, closely resemble those of SDHB-mutated human PCPGs, making it the most valid model now available. Strategies employed to develop RS0 may be broadly applicable to other SDH-deficient tumors.

Keywords: succinate dehydrogenase B, paraganglioma, pheochromocytoma, cluster 1, xenograft, cell culture, hypoxia, metabolome, model, rat

Introduction

Paraganglia are neuroendocrine structures that develop from neural crest progenitors associated with paraxial sympathetic nerves and from parasympathetic nerves in the head and neck. The major sympathetic paraganglion is the adrenal medulla. Tumors called paragangliomas can arise anywhere in the distribution of normal paraganglia. By definition an intra-adrenal paraganglioma (PG) is called a pheochromocytoma (PC) (Lloyd et al. 2017).

At least 40% of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (PCPGs) are hereditary, and germline mutations of at least 17 functionally diverse genes can lead to their development (Dahia 2017). Mutations of genes encoding subunits of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) account for the largest number of familial aggregates of these tumors and for more than 20–30% of the tumors that metastasize (Amar et al. 2005, 2007, Benn et al. 2006, Pasini & Stratakis 2009, Favier et al. 2015). Mutations of SDHB, which encodes the B subunit, confer the highest risk of metastasis (Crona et al. 2019, Hescot et al. 2019). Specifically, about 42% of SDHB mutation carriers develop pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas by the age of 70 (Jochmanova et al. 2017, Rijken et al. 2017), and up to almost 60% of the tumors have been reported to metastasize (Jochmanova et al. 2017). There is currently no cure after metastases occur. Further, there are few experimental models for pre-clinical testing of new treatments and no models that faithfully reflect the tumor phenotype.

Paragangliomas sort into clusters based on their transcriptome and associated phenotypic characteristics, which include signaling pathways, metabolism and hormonal function (Dahia et al. 2005, Richter et al. 2014, Castro-Vega et al. 2015, Favier et al. 2015, Fishbein et al. 2017, Fishbein & Wilkerson 2018). Tumors with gene mutations of SDH subunits fall into cluster 1, which is characterized by pseudohypoxic signaling and metabolism (Eisenhofer et al. 2017). In contrast, cluster 2, the second major aggregate of tumors, is associated predominantly with mutations of genes including RET and NF1 that affect kinase signaling. It is important for pre-clinical models to represent the appropriate tumor cluster as closely as possible because distinctive cluster-associated signaling and metabolic (Richter et al. 2014, Lussey-Lepoutre et al. 2015) characteristics can potentially serve as drug targets (Tella et al. 2017) or modify drug responses (Muir & Vander Heiden 2018). However, genetically engineered mice with Sdhb mutations have thus far failed to develop SDH-deficient PCPGs. Consequently, cluster 2 mouse tumor models are often used as imperfect surrogates (Lussey-Lepoutre et al. 2018).

In contrast to mice and other species, rats have an unusual proclivity to develop PCs. The incidence of these tumors increases throughout life and is especially high in males compared to females, with a ratio up to 10:1 in some rat strains (Tischler et al. 2014). Abdominal or head and neck PGs are also occasionally reported (van Zwieten et al. 1979, Hall et al. 1987, Li et al. 2013). In WT Sprague–Dawley rats, PCs begin to be detected at age 1–2 years, and the prevalence at 2 years is approximately 10% (Pace et al. 2002). The incidence is further increased by a variety of agents including high calorie diet, radiation, drugs and hormones (Tischler et al. 2004, 2014). In view of their innate proclivity to develop PCCs, we hypothesized that rats would a priori be superior to mice as a potential Sdhb tumor model. This communication describes the successful development of a new rat-derived xenograft and cell culture model that closely mirrors the characteristics of SDHB-associated human PCPGs.

Materials and methods

Origin and validation of the model

Heterozygous Sdhb+/- Sprague–Dawley rats were generated by a commercial supplier (Cyagen Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using the TALEN (transcription activator-like effector nuclease) technique (Merkert & Martin 2018). Four ‘F0’ founders were generated with various deletions in the rat Sdhb gene: a 1-base deletion in exon 1, a 13-base deletion in exon 1, a 7-base deletion in exon 2 and a 8-base deletion in exon 2. All of the mutations except the 1-base deletion successfully became germline on subsequent breeding. For each of the founder mutations, we tested liver tissue of heterozygous offspring for expression of rat Sdhb mRNA using a commercial TaqMan assay kit (Life Technologies). Enzymatic assays of liver tissue were also performed (Abcam Complex ll Enzyme Activity Microplate Assay Kit). Finally, as a bioassay to confirm biological significance of the Sdhb deletions, we bred male and female Sdhb+/- heterozygotes to each other and examined gravid uteri as a test for homozygous embryonic lethality. Sperm from rats with all three germline deletions is cryopreserved at the Rat Resource and Research Center (RRRC) at the University of Missouri (rrrc@missouri.edu), where it will be publicly available.

Development and harvesting of tumors

Thirty-five male Sdhb+/- rats with a 13-bp deletion in exon 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1, see section on supplementary materials given at the end of this article) formed the core of this study. Twenty-one of the animals were exposed to 5 Gy of gamma irradiation 1 week postnatally. The administration of postnatal irradiation was based on previous findings that irradiation of the parent animals contributed to the development of the rat-derived PC12 (Warren & Chute 1972) and mouse-derived MPC (Powers et al. 2000) PC cell lines. All were fed ad libitum on a standard rodent diet (Envigo/Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and were maintained until they were killed because of deteriorating health or were found dead. Necropsies were performed and the adrenal glands, pituitaries and carotid bodies were examined grossly and microscopically. Tissue from five PCs that appeared to be viable was injected subcutaneously into NSG mice as previously described (Powers et al. 2017). Xenografts of the PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cell line (passage 40), (Greene & Tischler 1976) were similarly prepared to serve as controls in relevant analyses.

Primary tumors and xenografts in consecutive passages were examined histologically and immunohistochemically as previously reported (Powers et al. 2018). Antibodies utilized are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Immunoblots and electron microscopy were also performed as previously described (Powers et al. 2018).

Cell cultures and development of cell lines

To generate primary cell cultures, minced xenograft tissue was dissociated in collagenase followed by trypsin (Powers et al. 2000). The dissociated cell suspension was plated in 35 mm culture dishes in a series of preliminary studies to test the effects of varied medium composition and O2 concentration in attempting to establish cell lines. The utilization of xenografts to develop cell lines, rather than vice versa, served to expand tumor cell populations because the usually small primary tumors did not provide sufficient numbers of cells for adequate tests of growth conditions. It further provided xenografts comparable to human patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, which are not derived from cell lines. This approach has been utilized by others for studies of human neuroblastomas (Persson et al. 2017).

Routine culture medium consisted of RPMI 1640 with 10% heat inactivated horse serum, 5% fetal bovine serum, glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin. This medium is employed in our laboratory to culture PC12 cells (Greene & Tischler 1976), normal rat chromaffin cells (Tischler et al. 1994) and mouse-derived MPC cells (Powers et al. 2000). Because SDH deficiency alters cells’ nutritional requirements (Lussey-Lepoutre et al. 2015), we compared cell growth and survival in this medium vs an enriched medium supplemented with non-essential amino acids, fatty acids, uridine and pyruvate that we recently employed for primary cultures of a SDH-deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) (Powers et al. 2018). These basal and enriched media were compared to serum-free stem cell media consisting either of DMEM/F12 with B27 Supplement plus FGF (20 ng/mL) and EGF (20 ng/mL) or serum-free RPMI 1640 with the same B27 and growth factor supplementation. Also, based on the gastrointestinal stromal tumor study, which showed deleterious effects of O2 on cell survival, we tested the effects of maintaining cultures in decreased oxygen concentrations (10%, 5% or 1%) compared to traditional ‘normoxic’ cultures (~20% O2, 95% air/5% CO2). In order to simultaneously compare multiple O2 concentrations, cultures were maintained in Billups-Rothenberg modular incubator chambers with pre-mixed gasses with increased N2 to compensate for decreased O2. CO2 concentration was constant at 5%. All cultures were maintained in a water-saturated atmosphere at 37°C. Double immunocytochemical staining for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (Tischler et al. 1992) was performed in order to distinguish the neoplastic chromaffin cells from fibroblasts, endothelial cells and other normal cell types. Two cell lines, designated RS0 (for rat Sdhb null) and RS1/2 (for Sdhb haploinsufficient), originated from cultures of xenografts derived from two different primary tumors and maintained in 5% O2.

Whole genome sequencing

DNA extraction

Cell line DNA was extracted using a Qiagen Blood and Cell Culture DNA kit (catalogue number 13362) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Matched normal DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of kidneys from the individual rats in which the primary RS0 and RS1/2 tumors originated, using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (catalogue number: 69504) with a slightly modified protocol. Samples were deparaffinized in xylene and subjected to an additional ethanol wash to remove residual xylene. Proteinase K digestion was carried out at 56°C over 3 days instead of overnight, with 12 µL proteinase K added every 24 h. The optional RNase A treatment was also carried out using 4 µL of RNase (100 mg/mL) at the end of the 3-day incubation.

WGS library preparation and sequencing

Libraries were prepared at The University of Melbourne Centre for Cancer Research (UMCCR) using the Illumina® TruSeq™ DNA Nano library preparation method according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two hundred nanograms of DNA was used as input and a 550-bp insert size was targeted. Samples were sequenced in separate batches on the Illumina® Nova-Seq 6000. QC stats including the mean read count and insert size from each sample can be seen in Supplementary Table 2.

WGS alignment and quality control

BCL files were demultiplexed and converted to FASTQ files with Illumina® bcl2fastq (version 2.20.0.422) with predominantly default settings (including adapter trimming). The -no-lane-splitting flag was also added as lanes were not used in this protocol. Alignment and variant calling steps were run as part of the validated bcbio-nextgen cancer somatic variant calling pipeline (version 1.1.3a) (https://github.com/bcbio/bcbio-nextgen). The bcbio-nextgen template that was used can be seen in Supplementary Table 7. The versions of all programs used by bcbio-nextgen are additionally shown in Supplementary Table 8. Briefly, the raw tumor and blood FASTQ files were first processed by Atropos (version 1.1.21) (Didion et al. 2017) to clip homopolymers (minimum 8 bases) from the ends of reads. Trimmed FASTQ files were aligned to the rat genome (version rn6) with BWA-mem (version 0.7.17) (Li 2013) with predominantly default settings. The two exceptions were that the -M flag was enabled to mark shorter split read hits as a secondary alignment and seeds with >250 occurrences were skipped (reduced from the default 500).

WGS variant calling

Germline variants were called by Varscan (version 2.4.3) (Koboldt et al. 2012), GATK HaplotypeCaller (GATK version 4.1.2.0) (McKenna et al. 2010, DePristo et al. 2011) and Strelka2 (version 2.9.10) (Kim et al. 2018) callers. Somatic variants were called by the Varscan (version 2.4.3), Mutect2 (GATK version 4.1.2.0) (Cibulskis et al. 2013) and Strelka2 (version 2.9.10) variant callers. In both instances, a variant was accepted as true if it was detected by two of the three callers. Variant allele frequency was calculated from VCFs produced from bcftools call of samtools mpileup. All variants were inspected manually using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) (Robinson et al. 2011) and somatic variants with some germline presence in difficult-to-sequence regions of the genome were removed. The effect of somatic variants was annotated by ensembl VEP (version 95.3). Mutation signatures were generated using MutationalPatterns (Blokzijl et al. 2018). Signatures used were single base substitution (SBS) signatures from COSMIC v3 (Alexandrov et al. 2019, Tate et al. 2019).

WGS copy number and structural variant calling

Somatic copy-number profiles were generated by running FACETS on the BCBio aligned BAM files with a rat-specific GC profile (calculated from the rn6 reference genome) and a cval of 1000. SVs were called separately with GRIDSS (version 2.0.0) (Cameron et al. 2017). The bam files used by GRIDSS were generated separately to those used for variant calling and CNV detection. Specifically, alignment was performed with BWA-mem (version 0.7.17) with default settings and duplicate marking was performed with samtools (version 1.9). Structural variants were annotated with the StructuralVariantAnnotation R package (https://github.com/PapenfussLab/StructuralVariantAnnotation).

Custom R analyses

All R analyses were performed with R (version 3.6.0) (https://www.r-project.org/). Circos plots were generated from GRIDSS and FACETS outputs using circlize (Gu et al. 2014).

Comparison of syntenic regions between human and rat chromosomes

A table of human-rat gene homology (hg38 vs rn6) was downloaded from ensembl biomart (ensembl release 96) (Zerbino et al. 2018). The database was then filtered down to the rat chromosomes altered in the RS0 model (8, 5, 9 and 14p). Rat cytoband data (rn6) were downloaded from the UCSC annotation database (Raney et al. 2014). The proportion of rat-human syntenic genes on each chromosome arm was then calculated by dividing the number of high confidence syntenic genes between arms by the total number of genes on the corresponding human chromosome. GISTIC (version 2.0.23) (Mermel et al. 2011) was run on copy-number variation (CNV) profiles of SDHB tumors obtained from the TCGA and Castro-Vega papers (Castro-Vega et al. 2015, Fishbein et al. 2017). The proportion of rat-human syntenic genes was then compared with the frequency of chromosome arm loss (defined as >50% of a chromosome arm) as reported by GISTIC.

Transcriptional profile

RNA sequencing was performed with an Illumina HiSeq 2000 at the Tufts genomics core facility. Paired-end RNA sequencing data were preprocessed using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al. 2014) to filter poor quality reads, then aligned using TopHat2 pipeline (Kim et al. 2013). FeatureCounts software (Liao et al. 2014) was used to map reads to genes, and edgeR (Robinson et al. 2010) was used to calculate RPKM (reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) (Powers et al. 2018).

Consensus clustering analysis

Rat genes were first mapped to human genes using the biomaRt R package (Durinck et al. 2005). The rat RNAseq data were then normalized using the same procedure that was applied to the human samples in the published TCGA analysis (Fishbein et al. 2017): rsem normalization, log2 transform and then gene median centered. Genes with 0 reads across all rat samples were removed. The top 3000 most-variable genes by median absolute deviation were selected for cluster discovery using ConsensusClusterPlus as was done for the human clustering (Wilkerson & Hayes 2010, Fishbein et al. 2017). We then mapped 1699 rat genes to these 3000 human genes and used these 1699 genes to do a cross-species consensus clustering for 173 human samples and 3 rat samples.

Metabolomics

Metabolomic analysis was performed as previously described (Powers et al. 2018). Briefly, unbiased metabolite profiling was performed using 1H NMR, and 13C-NMR was used to trace the metabolic fates of glucose and the contributions of glycolysis or anaplerotic TCA cycle pathways to the metabolite profile (Bruntz et al. 2017). Replicate s.c. xenograft nodules (each 1 cm in greatest dimension) were analyzed for RS0, RS1/2 and PC12. Pooled tissue from normal rat adrenal medullas was used as an additional SDH-intact control for 1H NMR profiling.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. with individual values displayed on graphs. Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc). Significance was tested using unpaired Student’s t-test, two tailed distribution with P < 0.05 set as significant.

Study approval

All animal procedures performed in these studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of Tufts University and Tufts Medical Center.

Genomics data availability

All WGS and RNA-seq data are available through NCBI short-read archive (SRA) (bioproject ID: PRJNA601534).

Results

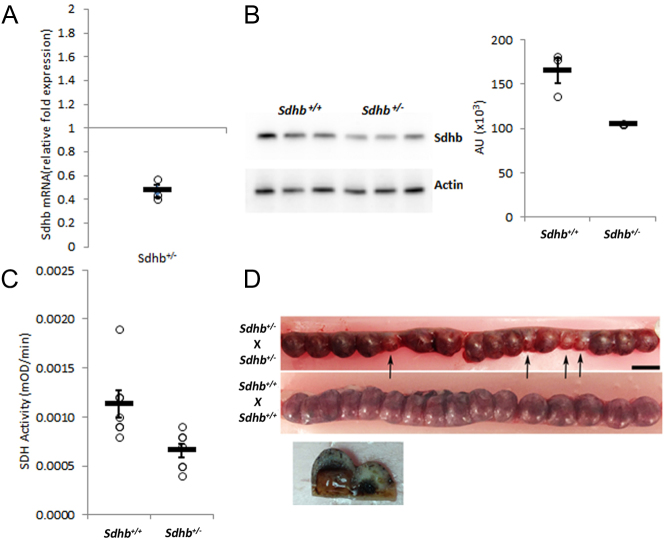

Liver tissue from heterozygous rats carrying each of the three germline Sdhb deletions showed approximately 50% reduced expression of Sdhb mRNA and enzyme activity compared to age-matched WT rats and 68% of normal protein expression based on densitometry data. The biological significance of haploinsufficiency was confirmed by crossing Sdhb +/- X Sdhb +/- rats to generate homozygotes, which resulted in embryos developmentally stalled at ~5–6 days, as reported for Sdhb -/- mice (Piruat et al. 2004). Approximately 25% of 32 embryos were affected, consistent with the percentage of homozygotes predicted by Mendelian genetics (Fig. 1). In contrast, only one embryo of 31 was stalled in control specimens from WT rats. Because of the apparent functional equivalence of all three Sdhb deletions, we arbitrarilly decided to focus on the largest (i.e. 13 base) deletion for colony expansion.

Figure 1.

Molecular and functional consequences of heterozygous Sdhb deletion. (A, B and C) Comparisons of liver tissue from 2-week-old heterozygous (Sdhb+/-) and WT (Sdhb+/+) rats. (A) Decreased Sdhb mRNA (n = 3 animals for each group, each point done in triplicate *P < 0.05). (B) Protein expression with densitometric analysis n = 3 *P < 0.05; and (C) decreased Sdh enzyme activity (n = 7 samples for each group, individual points done in duplicate) *P < 0.05. (D) Opened uteri from 12-day-old gravid rats showing stalled embryos in a representative heterozygous cross (top) compared to WT (bottom). Nine of 31 embryos examined were stalled in Sdhb+/-x Sdhb+/- vs 1 of 31 in in WT pregnancies (P = 0.0125).

The mean lifespan of rats harboring the 13-base deletion was 88.5 ± 3.0 weeks (range 67–105, n = 15) for the non-irradiated vs 69 ± 4 weeks (range 38–104, n = 20) for the irradiated group (P = 0.0001) and the mean lifespan of 130 weeks for normal Sprague–Dawley rats according to the supplier, Taconic Laboratories (Rensselaer, NY, USA). Macroscopic PCs ~0.3–0.6 cm in greatest dimension were present in three irradiated rats and one non-irradiated. In addition, one irradiated rat developed a carotid body PG. Multiple microscopic adrenal medullary lesions that were cytologically identical to PCs but did not invade or compress the adrenal cortex were present in three irradiated and four non-irradiated animals. Although similar microscopic lesions would be classified as hyperplastic nodules in veterinary pathology literature (Tischler et al. 2014), they are classified here as micro PCs in light of current understanding based on molecular studies of small adrenal medullary nodules in humans (Korpershoek et al. 2014). Multiple pituitary adenomas were present in both groups of rats, as shown in Supplementary Table 3.

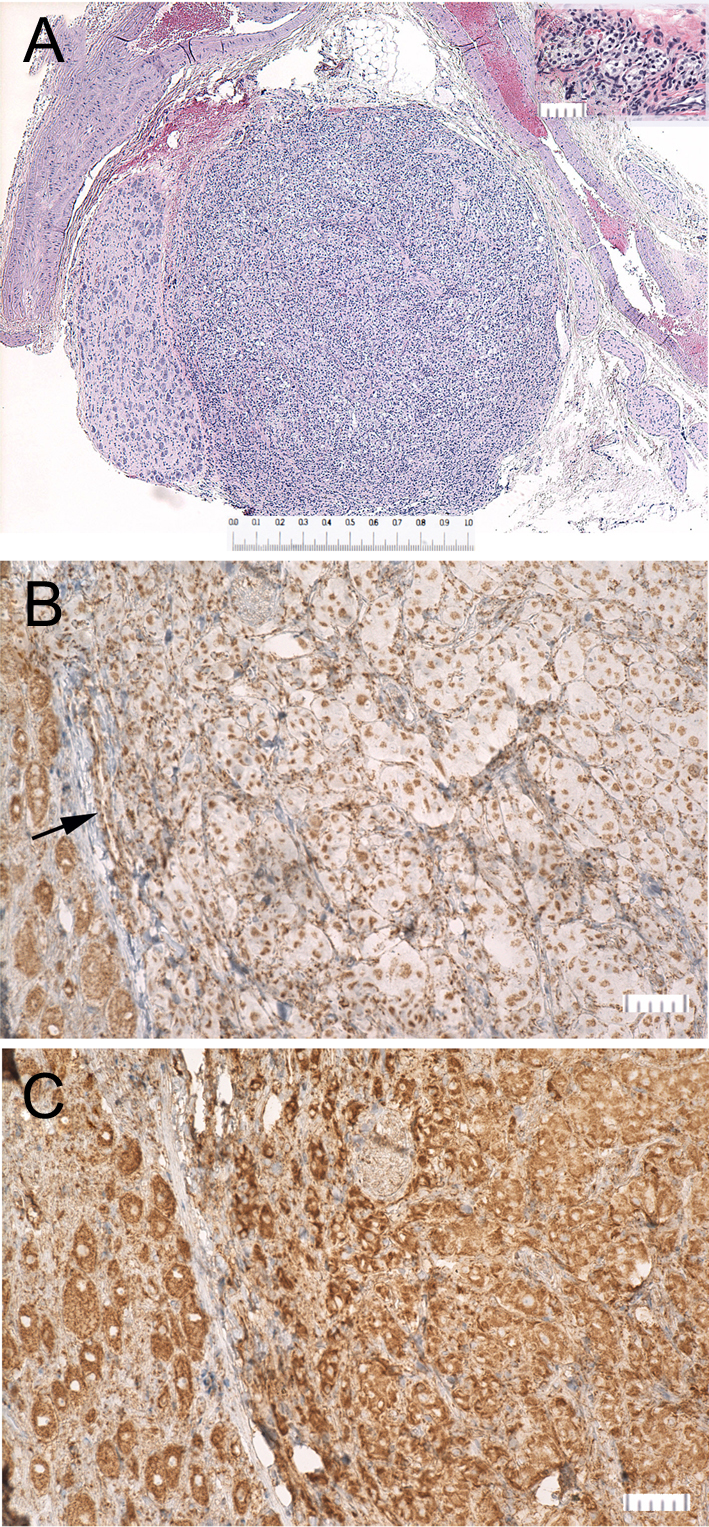

Two distinct, serially transplantable, PC xenograft models, which we have designated as RS0 and RS1/2, were derived at 84 weeks and 74 weeks, respectively, from macro PCs that arose in irradiated rats. RS0 xenografts histologically show sharply defined ‘Zellballen’ architecture, slightly clear cells and prominent blood vessels closely resembling human paragangliomas (Tischler & deKrijger 2015), while RS1/2 shows more diffuse growth (Fig. 2). As an initial screen for Sdh deficiency, both xenograft models and all primary tumors were stained immunohistochemically for SDHB protein (Dahia et al. 2005, van Nederveen et al. 2009). Only RS0 and the carotid body PG, which was too small to xenograft, were Sdhb-negative, as defined by loss of the granular cytoplasmic staining characteristic of intact SDHB (Figs 2C and 3B). Both were positive for SDHA, which is known to persist in SDH-deficient tumors caused by SDHB mutations (Korpershoek et al. 2011, Papathomas et al. 2015, Bezawork-Geleta et al. 2018). Additional immunohistochemical stains demonstrated diffuse immunoreactivity for tyrosine hydroxylase in both RS0 and RS1/2. All pituitary adenomas showed intact staining for both SDHA and SDHB.

Figure 2.

Histology and immunohistochemistry of pheochromocytoma xenografts RS0 (A, B, C and D) and RS1/2 (E, F, G and H). (A and E) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (B and F). Tyrosine hydroxylase RS0 shows classic ‘Zellballen’ pattern characteristic of pheochromocytomas and extra-adrenal paragangliomas, while RS1/2 shows diffuse growth. (C and G) SDHB. RS0 shows loss of granular cytoplasmic staining for Sdhb in tumor cells and retained dark granular staining in endothelial cells (arrows). In contrast RS1/2 shows positive staining in both tumor and endothelial cells. (D and H) SDHA. Both RS0 and RS1/2 show positive staining in tumor cells and endothelilium. Bar = 100 µm.

Figure 3.

Carotid body paraganglioma. (A) Carotid bifurcation containing a paraganglioma (center) and adjacent superior cervical ganglion (left); Bar = 1 mm. Inset shows the entire normal carotid body from an 18-month-old Sdhb+/- rat (Bar = 50 um). (B) Immunohistochemical stain for SDHB showing loss of granular cytoplasmic staining in tumor cells and retained dark granular staining in endothelial cells (arrow) and SCG neurons. (C) Tumor cells, neurons and endothelial cells show granular staining for SDHA.

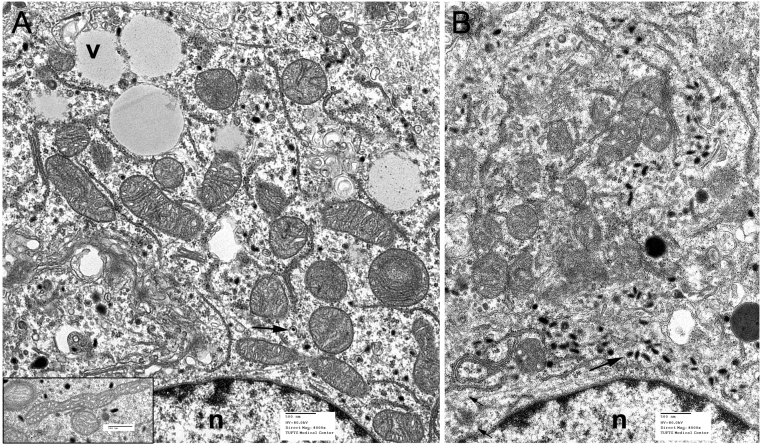

The most distinctive ultrastructural features of RS0 were relatively sparse secretory granules and cytoplasmic vacuoles similar to those in other SDH-deficient tumors (Powers et al. 2018). RS1/2 showed larger and more numerous secretory granules than RS0 and no cytoplasmic vacuoles (Fig. 4). An additional difference was that the mitochondria in some RS0 cells showed prominent tubular or branched cristae and were sometimes also elongated (Fig. 4 inset). These reactive changes have been observed in some SDH-deficient human tumors (Szarek et al. 2015) and can result from altered redox balance (Cogliati et al. 2016). However, the marked mitochondrial swelling and degeneration reported in the human tumor specimens and some other models (Douwes Dekker et al. 2003, Szarek et al. 2015, D’Antongiovanni et al. 2017, Powers et al. 2018) were not seen. The relatively mild mitochondrial changes in RS0 cells are consistent with a recent study indicating that immortalized Sdh-null cells derived from rodent chromaffin cells may be less bioenergetically compromised than Sdh-compromised cells of other types (Kluckova et al. 2020).

Figure 4.

Electron micrographs of RS0 (A) and RS1/2 xenografts (B). Arrows indicate neuroendocrine secretory granules; v, cytoplasmic vacuoles; n, nuclei. Characteristic features of RS0 are cytoplasmic vacuoles and sparse, often tiny secretory granules. In contrast, RS1/2, which is not SDH-deficient, has larger secretory granules and lacks cytoplasmic vacuoles. Inset at left shows elongated mitochondria with tubular cristae that were seen in some RS0 cells.

Cell culture and establishment of cell lines

Preliminary studies showed that cells derived from neither xenograft model would produce a cell line in an atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 and routine RPMI culture medium with 10% horse serum/5% fetal bovine serum. Under those conditions, RS0 cells rapidly accumulated large cytoplasmic vacuoles and died over a period of approximately 2 weeks. In contrast, RS1/2 cells survived for months and did not form vacuoles but slowly dwindled. Optimal cell survival was obtained in 5% O2, consistent with the beneficial effect of low O2 previously observed with SDH-deficient GIST (Powers et al. 2018). However, this was still insufficient to develop cell lines. We, therefore, next tested combinations of 5% O2 together with lowered-to-absent serum in medium with stem cell-promoting supplements (Persson et al. 2017). Under those conditions, RS0 cells proliferate as a continuous cell line in uncoated plastic culture dishes in serum-free medium as free-floating spheres with a doubling time of approximately 14 days (Fig. 5). A similar-appearing cell line growing in 5% O2 was also derived from RS1/2 cells. However, the RS1/2 line requires serum in a low concentration (1% HS/0.5% FBS). For both cell types, preliminary studies showed the use of RPMI 1640, as the base medium is slightly preferable or equivalent to the DMEM/F12 mixture widely used in stem cell cultures.

Figure 5.

Cell cultures of RS0 cells grown in serum free medium. (A) Darkfield photomicrograph showing typical appearance of tumor cell spheroids, which often form on top of cells attached to the culture dish, then detach and grow suspended in the medium. (B) Cytocentrifuge preparation showing a representative microsphere immunohistochemically stained for tyrosine hydroxylase (red cytoplasm) and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, black nuclei) after 7 days of BrdU labeling. White circles within the microsphere are unlabeled nuclei. Arrow indicates a labeled mitotic figure, indicating that incorporating BrdU can go on to divide. Bar = 100 µm.

Whole genome sequencing

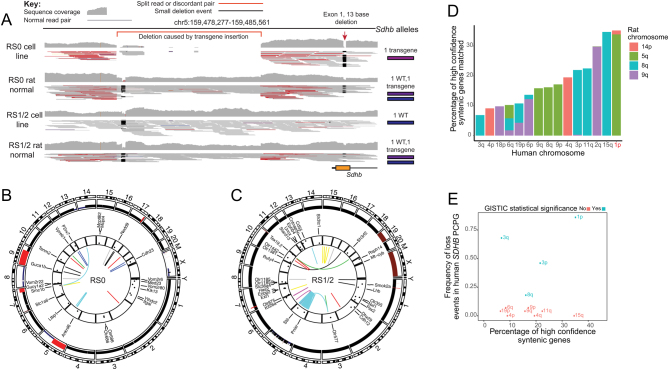

We performed WGS to verify genetic loss of WT Sdhb and to identify additional somatic changes in RS0 and RS1/2 tumor cells. WGS was initially performed on RS0 xenograft tissue; however, some ambiguities resulted from the presence of mouse DNA sequences introduced by the host animal. In order to obtain cleaner data, WGS was repeated using DNA extracted from RS0 and RS1/2 cultured cell lines devoid of mouse stromal and immune cells. Focused analysis of sequence coverage of Sdhb identified the expected 13-bp deletion in exon 1 plus a 729-bp deletion immediately upstream of the Sdhb promoter in the RS0 germline DNA (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6A, there is clear evidence of a 729-bp hemizygous deletion in both the normal germline DNA and tumour DNA of RS0 and RS1/2. The deletion is inferred by the sharp reduction in read depth at the genome co-ordinates upstream of SDHB as indicated and the paired reads that span the deletion, which are marked in red. The deletion was certainly a result of the TALEN process and not radiation. Inference of read coverage, and genome-wide copy-number analysis for cell line RS0 showed somatic segmental loss of chr5 including the WT Sdhb allele (Fig. 6B). In cell line RS1/2, we observed a chromothripsis involving chr5 resulting in loss of the TALEN-edited non-functional Sdhb allele but retention of the Sdhb WT allele (Fig. 6C). These data are in keeping with the negative SDHB protein expression in RS0 but positive SDHB staining in RS1/2.

Figure 6.

WGS of RS0 and RS1/2 tumor cell lines and their matched germline DNA. (A) Genome viewer snapshot of sequence coverage spanning exon 1 of Sdhb and the genomic region immediately 5′ of Sdhb (~1.4 kb in total). A 13-bp deletion within exon 1 of Sdhb was detected in the germline DNA of both RS0 and RS1/2. The exon 1 deletion was present in all sequencing reads in tumor cell line RS0, indicating that the WT Sdhb allele had been lost during tumorigenesis. Conversely, the TALEN-edited Sdhb allele was lost during tumorigenesis of tumour cell line RS1/2. In addition to the exon 1 deletion, a larger 729-bp deletion was also detected upstream of Sdhb, indicated by the presence of discordant or split reads spanning the deletion breakpoint (these reads are highlighted in red). The deletion upstream of Sdhb is also supported by a precipitous drop in sequence coverage spanning the 729-bp deletion. Like the 13-bp exon 1 deletion, the 729-bp deletion was detectable in the germline DNA of RS0 and RS1/2, indicating that it was introduced by TALEN gene-editing. (B) A circos plot describing the somatic alterations that occurred in the formation of RS0. From outside to inside, tracks are as follows: rat cytoband, total copy-number variation (CNV) as called by FACETS (black signifies n = 2, red signifies n > 2 and blue signifies n < 2), names of genes called by BCBio ensemble variant calling as having a coding mutation, the allele frequency of these mutations and the innermost track represents the structural variants called by GRIDSS. (C) A circos plot describing the somatic alterations that occurred in the formation of RS1/2. Tracks are in the same order as described in (B). (D) The percentage of high confidence orthologous genes matched between rat and human comparing chromosome arms called by FACETS as being altered in RS0 (either gain or loss). (E) Comparison of high confidence orthologous genes from D (further filtered only to chromosomal loss events in RS0) against the frequency of chromosomal arm level loss events in human SDHB PCPG as determined by GISTIC. Human copy-number variation (CNV) data were taken from publicly available copy-number profiles cited in the Materials and methods section. Chromosome arms colored in blue were called as statistically significantly altered by GISTIC (false discovery rate <0.05). Chromosome arm level losses of 1p, 3q, 3p and 8q are frequent and statistically significant events in human PCPG. These regions are overlapping with syntenic genomic regions that have undergone somatic loss in rat model RS0.

Both RS0 and RS1/2 cell lines had low mutation burden (RS0, 0.8 mutations/Mb; RS1/2 0.96 mutations/Mb). The highest proportion of base substitutions involved C>T transitions, but no dominant mutational signatures were observed in either cell line (Supplementary Fig. 2). With respect to mutations and structural alterations, no somatic lesions in gene orthologues previously found to be mutated in human PCPG were identified (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). A ~108-kb homozygous deletion involving exon 1 of Cdkna and complete loss of Cdkn2b was identified in cell line RS0. Inspection of the WGS sequence data in the matched xenograft, however, showed no evidence of this deletion event in the original RS0 tumor, therefore it was unlikely to be a founding event in RS0 tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. 3). In RS1/2, two mutations of unknown significance were detected in known cancer genes (Stil and Ext1). Furthermore, numerous structural alterations were identified in cell line RS1/2 involving chromothripsis of chromosome 5. Breakpoints were detected within cancer genes Arid1a Nfib and Psip1, the latter involving a gene fusion with Zbtb48. The principal driver gene mutation in RS1/2 is not apparent but may involve haploinsufficiency of one or more of these cancer genes or other genes on chr5. Interestingly, in cell line RS1/2 we observed a missense mutation at 10% variant allele frequency in cytochrome B (Mt-cyb). Despite the paucity of pathogenic mutations in both cell lines, we observed large segmental copy-number loss events in RS0 that are syntenic with frequently altered chromosomal regions in human SDHB-associated PCPG tumors (Fig. 6D and E). These events included syntenic loss of human chr1p, chr2q, chr3, chr8q and chr18p. We reasoned that these structural events are likely to be important in co-operating with SDHB loss of function to promote tumorigenesis, and provide further evidence that RS0 has the genomic hallmarks of human SDHB pheochromocytoma.

Metabolite profile

The presence of SDH deficiency was confirmed by high levels of succinate accumulation (Table 1). In RS0 xenografts, succinate was the third most abundant metabolite, in contrast to both RS1/2 and adrenal medulla. Lactate was the most abundant metabolite measured, consistent with increased production of lactate and induction of lactate dehydrogenase in SDH-deficient tumors and cell lines (Lussey-Lepoutre et al. 2015). In vivo 13C-glucose labeling showed robust incorporation of glucose into lactate and succinate and lesser incorporation into alanine and glutamate. The labeled glutamate contained almost the same amounts of (13C2-4,5)Glu and (13C2-2,3)Glu isoptomers, indicating approximately equal activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and pyruvate carboxylase (PC), respectively (Lussey-Lepoutre et al. 2015, Bruntz et al. 2017). This result is consistent with previous studies showing increased utilization of the anaplerotic pathway catalyzed by PC in Sdh-deficient mouse cell lines (Lussey-Lepoutre et al. 2015).

Table 1.

NMR metabolomic profiles of RS0, RS1/2 xenografts and rat adrenal medulla (RAM).

| RAM (20 pooled) | RS0 (n = 4) | RS1/2 (n = 3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± s.e.m. | Mean ± s.e.m. | ||||

| The ten most abundant detectable metabolites (µmol/mg of tissue) | |||||

| Epinephrine | 16.15 | Lactate | 15.18 ± 3.66 | Norepinephrine | 33.87 ± 29.41 |

| Norepinephrine | 12.33 | Taurine | 12.11 ± 2.69 | Lactate | 11.45 ± 2.18 |

| Glucose | 2.31 | Succinate | 5.99 ± 1.19 | Taurine | 10.38 ± 0.83 |

| Lactate | 0.89 | Glycine | 3.47 ± 0.75 | Ascorbate | 7.611 ± .42 |

| Taurine | 0.61 | Glutamate | 2.57 ± 0.58 | myo-Inositol | 6.33 ± 2.80 |

| ATP (or ADP) | 0.59 | Ascorbate | 2.57 ± 0.64 | Glutamate | 4.16 ± 0.97 |

| Ascorbate | 0.44 | Alanine | 2.08 ± 0.45 | Dopamine | 2.55 ± 2.04 |

| AMP | 0.30 | Creatine | 1.39 ± 0.28 | O-Phosphoethanolamine | 2.06 ± 0.25 |

| ADP (or ATP) | 0.21 | sn-Glycero-3-phosphocholine | 1.29 ± 0.34 | AMP | 1.85 ± 1.39 |

| Glutamate | 0.17 | myo-Inositol | 1.21 ± 0.26 | Betaine | 1.83 ± 0.31 |

| Succinate | 0.01 | Succinate | 0.29 ± 0.10 | ||

| 30 of 67 | 30 of 67 | ||||

| Catecholamine and metabolite profile (µmol per mg of tissue) | |||||

| Dopamine | 0.07 | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 2.55 ± 2.04 | ||

| 3,4-Dihydroxybenzeneacetatea | 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | ||

| Norepinephrine | 12.33 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 33.87 ± 29.41 | ||

| Normetanephrine | 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | ||

| Epinephrine | 16.15 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.81 ± 0.78 | ||

| Tyrosine | 0.00 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | ||

a3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC).

Similar to SDH-deficient human paragangliomas, the catecholamine profile of RS0 xenografts showed a predominance of dopamine, low levels of norepinephrine and undetectable epinephrine (Table 1).

Transcriptome and immunoblots

RS0 xenografts show high expression of canonical cluster 1 markers associated with the Hif2a regulatory network (Table 2) and with hereditary SDHB mutations in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (Fishbein et al. 2017) and previous comparable studies (Burnichon et al. 2011, Castro-Vega et al. 2015). These include Hif2a (also known as Epas1) and its targets including Vegfa and Adm (Table 2, and complete list in Supplementary Table 6). RNAseq also confirms the near total loss of Sdhb mRNA in RS0 xenografts, with residual low level expression consistent with the presence of blood vessels and other non-neoplastic cells (Fig. 2C). A novel finding is the presence of concomitant, though lesser, reduction in mRNA transcripts of other SDH subunits (Supplementary Table 6). Surprisingly, RS1/2 also shows modest reductions in multiple SDH subunits despite the presence of immunoreactive SDHB and a relatively low level of Hif2a (Supplementary Table 6).

Table 2.

RNAseq data comparing expression of Epas1 and genes in its regulatory network in RS0 and RS1/2 xenografts and pooled rat adrenal medullas (RAM).

| Genea | RAM (RPKMb) | RS0 (RPKM) | RS1/2 (RPKM) | RS0/RAM | RS1/2/RAM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epas1 | 80.01 | 1074.63 | 76.62 | 13.43 | 0.96 |

| Egln3 | 1.44 | 23.29 | 0 | 16.17 | 0 |

| Bhlhe40 | 10.99 | 114.0 | 11.77 | 10.37 | 1.07 |

| Vegfa | 51.43 | 607.36 | 62.04 | 11.81 | 1.21 |

| Twist1 | 1.86 | 14.82 | 0.50 | 7.95 | 0.27 |

| Serpine1 | 2.65 | 241.62 | 5.9 | 91.18 | 2.23 |

| Adora2a | 5.41 | 593.88 | 2.99 | 109.78 | 0.55 |

aGenes listed are from the NCBI HIF-2-alpha transcription Network (Biosystems NCBI, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/biosystems/137956?Sel=geneid:2034#show=genes). Those with the highest in the ratios in RS0 to RAM are shown. bRaw data are expressed as reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM). The constitutive expression of Epas1 in RAM is consistent with findings in normal embryos (Favier et al. 1999).

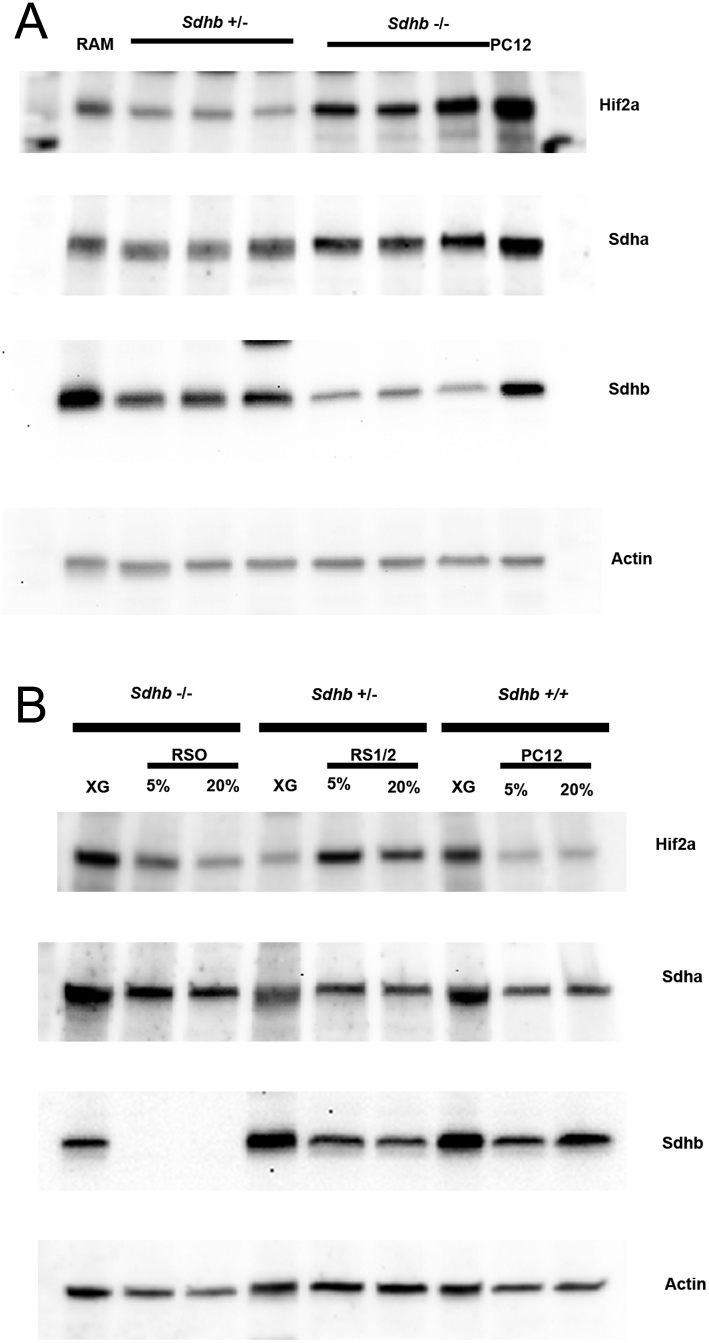

To further test how expression of the critical markers HIF2A and SDHB at the protein level correlates with immunohistochemical and RNAseq data, immunoblots of RS0 and RS1/2 xenografts were probed for these proteins in parallel with their corresponding cell lines. The PC12 rat pheochromocytoma, which is known to express HIF2A (Bechmann et al. 2019) but be Sdhb- intact, served as a positive control. In xenograft tissue, RS0 shows high HIF2A expression consistent with its high expression at the RNA level, while expression in RS1/2 is relatively low. Interestingly, in cell cultures this pattern is reversed as a result of increased expression in RS1/2. Cell cultures also show that protein expression is not completely unresponsive to O2 concentration in either RS0 or RS1/2 cells. Importantly, however, expression in RS0 cells at 5% O2, which approximates the concentration in solid tumors (Carreau et al. 2011), is comparable to expression in xenograft tumor tissue (Fig. 7). Immunoblots confirm the loss of SDHB in RS0 cells, while SDHA is both retained and slightly increased in primary Sdhb-/- vs Sdhb+/- xenografts (Fig. 7A) and in RS0 compared to RS1/2 cells (Fig. 7B). This increase may be related to a reported role of Sdha in an alternate assembly of respiratory complex 2 that decreases metabolite synthesis and cell proliferation in response to knockdown of SDHB (Bezawork-Geleta et al. 2018).

Figure 7.

Immunoblots for HIF2A, SDHB and SDHA. (A) Representative immunoblot comparing levels of HIF2A, SDHB and SDHA in RS0 and RS1/2 xenografts. A single immunoblot from a 4–15% gradient polyacrylamide gel was consecutively probed, stripped and re-probed for each of the indicated proteins. RAM (rat adrenal medulla) and PC12 (xenograft produced in NSG mouse from passage 40 cells) were run as controls. (B) Representative immunoblot comparing RS0, RS1/2 and PC12 xenograft tissue (XG) to corresponding cell lines in culture maintained in either 5% or 20% O2. Single immunoblot stripped and reprobed as in panel A.

Cross-species clustering analysis

In the TCGA study, consensus clustering divided 173 human samples of PC/PGs tumors into four molecularly defined groups: a kinase signaling subtype, a pseudohypoxia subtype, a WNT-altered subtype and a cortical admixture subtype (Fishbein et al. 2017). We performed cross-species consensus clustering analysis to test where among those subtypes the rat tumor samples would correspond. To do this, the rat RNAseq data were first analyzed to identify human homologs among the 3000 most highly expressed SDHB-associated genes used in the TCGA study. This yielded a set of 1699 overlapping genes. Consensus clustering was performed as described in Methods. First, using the 1699 gene sample set to re-analyze the TCGA data, the vast majority of the human TCGA data sets clustered to the same group as originally described for the 3000 genes in the published TCGA study, indicating that the reduced consensus sample set does not adversely affect the clustering results. When all three rat samples were then clustered with the human samples, the rat samples were all clustered together, indicating that the rat samples are more similar to each other than to the human samples (Supplementary Fig. 4A). To avoid this complication, each rat sample was clustered individually with the human samples in order to minimize the species effects. When this was done, all three rat tissue samples, rat adrenal medulla, RS0 and RS1/2, were clustered with the human pseudohypoxic cluster (Supplementary Fig. 4B, C and D).

Discussion

We have developed two serially transplantable xenograft and cell line PC models, which we call RS0 and RS1/2, from rats with a heterozygous germline deletion in Sdhb. RS0, which is Sdh deficient, is genomically comparable to its human counterpart and differs from existing models in that it arose in an animal with a hereditary Sdhb mutation. RS 1/2, which was derived from a different primary PC, has lost the mutated Sdhb allele retains one WT allele. RS1/2 shows some succinate accumulation consistent with haploinsufficiency but is not fully Sdh deficient. It differs from RS0 in showing intact staining for SDHB, a greater degree of neuroendocrine differentiation and a largely different transcriptome, although some markers are shared. RS1/2 serves both as a control for studies of RS0 and as a potential tool for studying patients’ tumors that may be haploinsufficient for SDH but have undetermined driver mutations. The main focus of this communication is on RS0 and RS1/2 xenografts, which would have the greatest immediate relevance to human tumors in vivo. Subsequent publications will entail detailed characterization of the cell lines and their applications.

RS0 and RS1/2 originated and have been maintained in the form of xenografts that were never in cell culture – that is, the equivalent of early passage human PDX models. They may therefore be especially valuable for pre-clinical drug testing. These xenografts grow slowly enough to faithfully represent aggressive human PGs, but rapidly enough to be practical for testing and imaging. Since there is a pending clinical trial of an EPAS1 inhibitor for metastatic PG (NCT02974738) (Tella et al. 2017), RS0 xenografts might be immediately relevant for pre-clinical drug testing as well as basic research. Features that RS0 xenografts share with SDH-deficient human PGs include identical histology (Tischler & deKrijger 2015), loss of SDHB protein with retention of SDHA (Korpershoek et al. 2011, Papathomas et al. 2015) and expression of the neuroendocrine markers TH and chromogranin A (Letouze et al. 2013). The presence of these markers indicates that they are not an irrelevant or dedifferentiated cell type, while the relatively low expression is comparable to that in human tumors (Letouze et al. 2013). Shared molecular markers include accumulation of a high concentration of succinate, metabolic rewiring and a transcriptional profile including high expression of multiple markers directly sensitive to impaired electron transport or hypoxia. The latter include Hif2a and its downstream targets including Vegfa.

Several highly expressed genes in RS0 xenografts are strong direct indicators of adaptive responses to the pathobiology of SDH deficiency. These include Cox4i2 (cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4I2), which catalyzes electron transfer from reduced cytochrome c to oxygen, and Ndufa4l2 (mitochondrial complex associated like 2), which encodes a subunit of Complex I of the respiratory chain. These markers are two of the three ‘exemplar genes’ cited in the TCGA study for being consistently associated with pseudohypoxia in human PGs (Fishbein et al. 2017) and Ndufa4/2 is of particular interest in that complex 1 activity is reportedly upregulated in SDHB mutated human PGs (Pang et al. 2018). However, the third exemplar gene, Ntng2 (netrin-G2) which modulates development of neuronal circuits and is less obviously related to SDH deficiency, is also not highly expressed in RS0. This is the case for many, but not all, other apparent mismatches. Notably, the hypoxia-inducible factor Egln3 (egl-9 family hypoxia-inducible factor 3, also known as Phd3), which is highly expressed in RS0, has been strongly associated with pseudohypoxia in VHL but not SDHB- mutated human tumors (Burnichon et al. 2011). While the transcriptome of RS0 is not a perfect match to human cluster 1, many of the mismatches that are peripherally related to the primary functional defects might reflect different species, different anatomic sites (Fliedner et al. 2018) and different cells of origin within an anatomic site or different developmental stages in which the human vs rat tumors originate. A particular finding suggesting an influence of developmental stage is the overexpression of Ret in RS0. Ret is widely expressed in early adrenal development but is then downregulated in maturing chromaffin cells and maintained in neurons (Powers et al. 2009).

An important aspect of this study is the use of normal adrenal medullary tissue as a reference. This contrasts with profiling studies of human PCPG, in which the different tumor clusters were compared only to each other and to an unrelated reference DNA (Burnichon et al. 2011, Fishbein et al. 2017). By specifically focusing on large differences between a tumor and its tissue of origin, rather than solely between subsets of tumors, it may be possible to find new drug targets in the HIF2A transcription network that entail fewer systemic side effects than targeting HIF2A itself. Hypothetically, those systemic effects could include depletion of normal stem cells (Hammarlund et al. 2018). A disadvantage of normal adrenal medulla is the potential confounding effect of residual adrenal cortex, which is inevitably present, in some analyses. However, by selectively focusing on large differences in specific markers, it is possible to discern distinctive characteristics of the cells of interest, as shown in the TCGA ‘cortical admixture’ cluster. In addition, it may be possible to calculate the proportion of cortical contamination (Fliedner et al. 2010). An interesting observation in this study was that carefully dissected normal rat adrenal medulla clustered in the pseudohypoxic group. While this might partly represent an artifact of cross-species clustering, it is consistent with previous reports of HIF2A expression in normal sympathoadrenal development and function (Favier et al. 1999, Richter et al. 2013).

Although PDX-like xenografts are an excellent model for pre-clinical drug testing (Shultz et al. 2014), cell lines are needed for mechanistic studies. Availability of cell lines also makes models accessible to many more researchers than those who would work with xenografts alone. Our cell culture studies were undertaken both to establish cell lines from RS0 and RS1/2 xenografts and to test whether non-conventional culture conditions that we previously demonstrated to be favorable to survival of cells from a unique SDH-deficient human GIST (Powers et al. 2018) would apply to these new models. Our results replicated our previous finding that routine ‘normoxic’ culture conditions are deleterious. In addition, we demonstrated an adverse effect of serum, which has been reported by others in PDX-derived cultures of human neuroblastoma. The deleterious effect of oxygen is not surprising because pO2 in vivo has been measured at ~41 mm Hg in normal liver (equivalent to ~5% O2) and ranged from 0–54 mm Hg in tumors of different types (Carreau et al. 2011). In both normal and neoplastic cells, low O2 may help to maintain stem cells (Hammarlund et al. 2018). The beneficial effects that we observed with low or absent serum and stem cell-promoting medium supplements in establishing the RS0 and RS1/2 cell lines is entirely consistent with a recent report by Persson et al. that neuroblastoma cells cultured from human patient-derived xenografts differentiate in serum but remain tumorigenic when propagated in stem cell medium (Persson et al. 2017). It remains to be determined how these new insights will affect future efforts to develop cell lines of human PC and PG. However, our cell culture findings and those of others suggest a need for radical departure from conventional methods, perhaps especially for SDH-deficient tumors. This applies both to model development and pre-clinical drug testing, which is usually conducted in 95% air/5% CO2 and may thereby exaggerate the efficacy of many chemotherapeutic agents (Carreau et al. 2011). However, individual tumors and different tumor types (Burgess et al. 2017) will likely require individualized culture conditions. It is well known that genetic and epigenetic characteristics of individual cancers and types of cancer can dictate different approaches to treatment (Burgess et al. 2017).

Multiple factors likely contributed to the development of these new rat models, including the innate proclivity of aging rats to develop PCs, combined with postnatal irradiation. Both of these have previously been reported for other rodent PC models (Powers et al. 2000). Very little is known about the genetic changes underlying the general susceptibility of rats to pheochromocytomas. The most extensively characterized and relevant model is MENX, which is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in Cdkn1b, which encodes the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1. This change was not found in RS0 or RS1/2, and, to our knowledge, whole genome sequencing has not been performed on MENX rats. Comparisons of these might yield useful information. It is plausible that, in our models, radiation caused somatic genetic changes that accelerated the growth of spontaneous PCs and caused one of the tumors to become SDH deficient. However, consistent with human PCPG, both RS0 and RS1/2 had very low mutation burdens, very few gene coding mutations and relatively stable genomes. Chromothripsis of chr5 caused by a single catastrophic event was likely important for tumorigenesis of RS1/2, and exposure to ionizing radiation may be implicated. However, chromothripsis is also a feature of some primary human PCPG (Flynn et al. 2015), which ostensibly arises in the absence of radiation exposure.

As in human PCPG, few co-operative DNA mutations could be found in rat PC and the tumor genome is typified by recurrent chromosomal arm level loss events resulting in presumed haploinsufficiency of multiple genes. Chromosomal loss events syntenic with recurrently altered chromosomal regions in human SDHB-associated PCPG indicate that the RS0 model faithfully represents the genome of human PCPG and therefore may be useful for dissecting therapeutic vulnerabilities based on common co-operative somatic changes. A homozygous deletion was detected in cell line RS0 involving two neighboring tumor suppressor genes Cdkn2a and Cdkn2b. This event is predicted to cause complete loss of function of the protein p19ARF, which is encoded by an alternative reading frame of Cdkn2a. p19ARF is a negative regulator of MDM2 and loss of p19ARF is known to cause indirect suppression of p53 through the ARF-MDM2-p53 tumor-suppressor axis (Eischen et al. 1999). However, because the Cdkn2a deletion was not detected in the RS0 xenograft, it most likely was not involved in early tumorigenesis of RS0. The existence of the Cdkn2a deletion may further increase the relevance of the RS0 cell line as a pre-clinical model because p16INK4A/Cdkn2a gene expression is frequently downregulated in human PCPG, either by genetic abnormalities or promoter methylation (Muscarella et al. 2008), and is associated with poor prognosis (Kiss et al. 2008).

Two hypotheses were implicit in the protocol design and outcome this study. The first is that unpredictable haploinsufficiencies resulting from radiation damage or other causes may account for features required for tumorigenesis in addition to loss of Sdhb, likening the RS0 model to human PCPG. This might explain why previous (’clean’) gene knockouts of SDH subunits in various combinations with targeted loss of selected tumor suppressors, for example, in mice, have failed, because of their inability to achieve these other genetic effects. The second hypothesis is that rats are innately more susceptible than mice to this type of tumor. It is therefore of interest that we unsuccessfully tested a similar protocol in mice prior to undertaking the rat project. The radiation protocol was used initially by Jacks et al. to increase the frequency of pheochromocytomas in heterozygous Nf1 knockout mice (Jacks et al. 1994) and then in our laboratory to establish the derivative MPC cell lines (Tischler et al. 1995, Powers et al. 2000). Even more important than radiation, outbreeding of the 129SVNf1 +/- mutation carriers to WT C57BL6 mice was essential for tumorigenesis, possibly reflecting different levels of tumor suppressor genes expressed in different mouse strains (Hawes et al. 2007). In attempting to develop a Sdhb-null mouse model, we followed exactly the protocol previously used to develop MPC cells. We obtained four male 129SVSdhb +/- mice from Dr Louis Maher at the Mayo Clinic (Maher et al. 2011) and outbred them to WT C57BL6 mice. Over the ~2-year lifespan study, pheochromocytomas developed in 3 of 44 irradiated Sdhb+/- mice and 1 of 10 in irradiated WT mice. However, all of the tumors were Sdh-intact by immunohistochemistry and none gave rise to cell lines (previously unpublished data). Cumulatively, our experience suggests that the success of the present project resulted from favorable features of rat biology together with irradiation. However, it is possible that a comparable mouse model might still be developed using mice with a different genetic background or by using a larger number of mice.

In summary, we have developed xenograft and cell line models called RS0 and RS1/2 from PCs that arose in rats with a heterozygous germline mutation in Sdhb. RS0 closely recapitulates the genotype and phenotype of hereditary SDHB-mutated human PCPG and appears to be a promising model for pre-clinical studies of these tumors. In addition, we identified a carotid body paraganglioma that also appeared to be SDH-deficient based on immunohistochemistry. That tumor was too small to graft or culture and it is possible that additional small paragangliomas were missed amid the large amount of fat in aged rats. This new model may be useful both for pre-clinical drug testing and for basic research aimed at understanding mechanisms involved in the development and progression of SDH-deficient human PCPG.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This research was supported principally by grants to A S T from the SDHB Pheo Para Coalition, the Pheo Para Alliance and the Paradifference Foundation and by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD, NIH. The work utilized NMR instrumentation purchased from a National Institutes of Health SIG grant (S10OD020073). A D P is supported by the Joseph Herman Trust. R W T is supported by a fellowship from the Victorian Cancer Agency.

Author contribution statement

J P and A T conceived the study, designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. B C and X Z performed RNA sequencing and analyzed the data. R T and A D P performed whole genome sequencing and analyzed the data. J D B performed metabolomic experiments and analyzed the data. Y O designed the TALEN. I L and A S-B performed immunohistochemical studies. H D S, S J M, T L and K T S contributed to experiments on hypoxic signaling and redox balance. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Kym Pham and Oliver Hoffman of the University of Melbourne Centre for Cancer Research Genomic and Bioinformatics Platform Groups for their contributions.

References

- Alexandrov LB, Kim J, Haradhvala NJ, Huang MN, Ng AW, Wu Y, Boot A, Covington KR, Gordenin DA, Bergstrom EN, et al 2019. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 578 94–101. ( 10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar L, Bertherat J, Baudin E, Ajzenberg C, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Chabre O, Chamontin B, Delemer B, Giraud S, Murat A, et al 2005. Genetic testing in pheochromocytoma or functional paraganglioma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 23 8812–8818. ( 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar L, Baudin E, Burnichon N, Peyrard S, Silvera S, Bertherat J, Bertagna X, Schlumberger M, Jeunemaitre X, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, et al 2007. Succinate dehydrogenase B gene mutations predict survival in patients with malignant pheochromocytomas or paragangliomas. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 92 3822–3828. ( 10.1210/jc.2007-0709) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechmann N, Poser I, Seifert V, Greunke C, Ullrich M, Qin N, Walch A, Peitzsch M, Robledo M, Pacak K, et al 2019. Impact of extrinsic and intrinsic hypoxia on catecholamine biosynthesis in absence or presence of Hif2alpha in pheochromocytoma cells. Cancers 11 E594 ( 10.3390/cancers11050594) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn DE, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Reilly JR, Bertherat J, Burgess J, Byth K, Croxson M, Dahia PL, Elston M, Gimm O, et al 2006. Clinical presentation and penetrance of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma syndromes. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 91 827–836. ( 10.1210/jc.2005-1862) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezawork-Geleta A, Wen H, Dong L, Yan B, Vider J, Boukalova S, Krobova L, Vanova K, Zobalova R, Sobol M, et al 2018. Alternative assembly of respiratory complex II connects energy stress to metabolic checkpoints. Nature Communications 9 2221 ( 10.1038/s41467-018-04603-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokzijl F, Janssen R, van Boxtel R, Cuppen E. 2018. MutationalPatterns: comprehensive genome-wide analysis of mutational processes. Genome Medicine 10 33 ( 10.1186/s13073-018-0539-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30 2114–2120. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruntz RC, Lane AN, Higashi RM, Fan TW. 2017. Exploring cancer metabolism using stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM). Journal of Biological Chemistry 292 11601–11609. ( 10.1074/jbc.R117.776054) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess MR, Hwang E, Mroue R, Bielski CM, Wandler AM, Huang BJ, Firestone AJ, Young A, Lacap JA, Crocker L, et al 2017. KRAS allelic imbalance enhances fitness and modulates MAP kinase dependence in cancer. Cell 168 817.e15–829.e15. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnichon N, Vescovo L, Amar L, Libe R, de Reynies A, Venisse A, Jouanno E, Laurendeau I, Parfait B, Bertherat J, et al 2011. Integrative genomic analysis reveals somatic mutations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Human Molecular Genetics 20 3974–3985. ( 10.1093/hmg/ddr324) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DL, Schroder J, Penington JS, Do H, Molania R, Dobrovic A, Speed TP, Papenfuss AT. 2017. GRIDSS: sensitive and specific genomic rearrangement detection using positional de Bruijn graph assembly. Genome Research 27 2050–2060. ( 10.1101/gr.222109.117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreau A, El Hafny-Rahbi B, Matejuk A, Grillon C, Kieda C. 2011. Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 15 1239–1253. ( 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01258.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Vega LJ, Letouze E, Burnichon N, Buffet A, Disderot PH, Khalifa E, Loriot C, Elarouci N, Morin A, Menara M, et al 2015. Multi-omics analysis defines core genomic alterations in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Nature Communications 6 6044 ( 10.1038/ncomms7044) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Sivachenko A, Jaffe D, Sougnez C, Gabriel S, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G. 2013. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nature Biotechnology 31 213–219. ( 10.1038/nbt.2514) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogliati S, Enriquez JA, Scorrano L. 2016. Mitochondrial cristae: where beauty meets functionality. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 41 261–273. ( 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.01.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crona J, Lamarca A, Ghosal S, Welin S, Skogseid B, Pacak K. 2019. Genotype-phenotype correlations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocrine-Related Cancer 26 539–550. ( 10.1530/ERC-19-0024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahia PLM. 2017. Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas, genetically diverse and minimalist, all at once! Cancer Cell 31 159–161. ( 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.01.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahia PL, Ross KN, Wright ME, Hayashida CY, Santagata S, Barontini M, Kung AL, Sanso G, Powers JF, Tischler AS, et al 2005. A HIF1alpha regulatory loop links hypoxia and mitochondrial signals in pheochromocytomas. PLoS Genetics 1 72–80. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Antongiovanni V, Martinelli S, Richter S, Canu L, Guasti D, Mello T, Romagnoli P, Pacak K, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, et al 2017. The microenvironment induces collective migration in SDHB-silenced mouse pheochromocytoma spheroids. Endocrine-Related Cancer 24 555–564. ( 10.1530/ERC-17-0212) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, Philippakis AA, del Angel G, Rivas MA, Hanna M, et al 2011. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nature Genetics 43 491–498. ( 10.1038/ng.806) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didion JP, Martin M, Collins FS. 2017. Atropos: specific, sensitive, and speedy trimming of sequencing reads. PeerJ 5 e3720 ( 10.7717/peerj.3720) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douwes Dekker PB, Hogendoorn PC, Kuipers-Dijkshoorn N, Prins FA, van Duinen SG, Taschner PE, van der Mey AG, Cornelisse CJ. 2003. SDHD mutations in head and neck paragangliomas result in destabilization of complex II in the mitochondrial respiratory chain with loss of enzymatic activity and abnormal mitochondrial morphology. Journal of Pathology 201 480–486. ( 10.1002/path.1461) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durinck S, Moreau Y, Kasprzyk A, Davis S, De Moor B, Brazma A, Huber W. 2005. BioMart and Bioconductor: a powerful link between biological databases and microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics 21 3439–3440. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti525) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eischen CM, Weber JD, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ, Cleveland JL. 1999. Disruption of the ARF-Mdm2-p53 tumor suppressor pathway in Myc-induced lymphomagenesis. Genes and Development 13 2658–2669. ( 10.1101/gad.13.20.2658) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer G, Klink B, Richter S, Lenders JW, Robledo M. 2017. Metabologenomics of phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an integrated approach for personalised biochemical and genetic testing. Clinical Biochemist: Reviews 38 69–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favier J, Amar L, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. 2015. Paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma: from genetics to personalized medicine. Nature Reviews: Endocrinology 11 101–111. ( 10.1038/nrendo.2014.188) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favier J, Kempf H, Corvol P, Gasc JM. 1999. Cloning and expression pattern of EPAS1 in the chicken embryo. Colocalization with tyrosine hydroxylase. FEBS Letters 462 19–24. ( 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01476-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein L, Wilkerson MD. 2018. Chromaffin cell biology: inferences from the Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell and Tissue Research 372 339–346. ( 10.1007/s00441-018-2795-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein L, Leshchiner I, Walter V, Danilova L, Robertson AG, Johnson AR, Lichtenberg TM, Murray BA, Ghayee HK, Else T, et al 2017. Comprehensive molecular characterization of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Cancer Cell 31 181–193. ( 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.01.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliedner SM, Breza J, Kvetnansky R, Powers JF, Tischler AS, Wesley R, Merino M, Lehnert H, Pacak K. 2010. Tyrosine hydroxylase, chromogranin A, and steroidogenic acute regulator as markers for successful separation of human adrenal medulla. Cell and Tissue Research 340 607–612. ( 10.1007/s00441-010-0965-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliedner SMJ, Brabant G, Lehnert H. 2018. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: genotype versus anatomic location as determinants of tumor phenotype. Cell and Tissue Research 372 347–365. ( 10.1007/s00441-017-2760-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn A, Benn D, Clifton-Bligh R, Robinson B, Trainer AH, James P, Hogg A, Waldeck K, George J, Li J, et al 2015. The genomic landscape of phaeochromocytoma. Journal of Pathology 236 78–89. ( 10.1002/path.4503) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene LA, Tischler AS. 1976. Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. PNAS 73 2424–2428. ( 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2424) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Gu L, Eils R, Schlesner M, Brors B. 2014. Circlize implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics 30 2811–2812. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu393) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LB, Yoshitomi K, Boorman GA. 1987. Pathologic features of abdominal and thoracic paragangliomas in F344/N rats. Veterinary Pathology 24 315–322. ( 10.1177/030098588702400405) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarlund EU, von Stedingk K, Pahlman S. 2018. Refined control of cell stemness allowed animal evolution in the oxic realm. Nature Ecology and Evolution 2 220–228. ( 10.1038/s41559-017-0410-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes JJ, Tuskan RG, Reilly KM. 2007. Nf1 expression is dependent on strain background: implications for tumor suppressor haploinsufficiency studies. Neurogenetics 8 121–130. ( 10.1007/s10048-006-0078-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hescot S, Curras-Freixes M, Deutschbein T, van Berkel A, Vezzosi D, Amar L, de la Fouchardiere C, Valdes N, Riccardi F, Do Cao C, et al 2019. Prognosis of malignant pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (MAPP-Prono study): a European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors retrospective study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 104 2367–2374. ( 10.1210/jc.2018-01968) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Shih TS, Schmitt EM, Bronson RT, Bernards A, Weinberg RA. 1994. Tumour predisposition in mice heterozygous for a targeted mutation in Nf1. Nature Genetics 7 353–361. ( 10.1038/ng0794-353) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jochmanova I, Wolf KI, King KS, Nambuba J, Wesley R, Martucci V, Raygada M, Adams KT, Prodanov T, Fojo AT, et al 2017. SDHB-related pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma penetrance and genotype-phenotype correlations. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 143 1421–1435. ( 10.1007/s00432-017-2397-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. 2013. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biology 14 R36 ( 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Scheffler K, Halpern AL, Bekritsky MA, Noh E, Kallberg M, Chen X, Kim Y, Beyter D, Krusche P, et al 2018. Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nature Methods 15 591–594. ( 10.1038/s41592-018-0051-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss NB, Geli J, Lundberg F, Avci C, Velazquez-Fernandez D, Hashemi J, Weber G, Hoog A, Ekstrom TJ, Backdahl M, et al 2008. Methylation of the p16INK4A promoter is associated with malignant behavior in abdominal extra-adrenal paragangliomas but not pheochromocytomas. Endocrine-Related Cancer 15 609–621. ( 10.1677/ERC-07-0285) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluckova K, Thakker A, Vettore L, Escribano-Gonzalez C, Hindshaw RL, Tearle JLE, Goncalves J, Kaul B, Lavery GG, Favier J, et al 2020. Succinate dehydrogenase deficiency in a chromaffin cell model retains metabolic fitness through the maintenance of mitochondrial NADH oxidoreductase function. FASEB Journal 34 303–315. ( 10.1096/fj.201901456R) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. 2012. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Research 22 568–576. ( 10.1101/gr.129684.111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpershoek E, Favier J, Gaal J, Burnichon N, van Gessel B, Oudijk L, Badoual C, Gadessaud N, Venisse A, Bayley JP, et al 2011. SDHA immunohistochemistry detects germline SDHA gene mutations in apparently sporadic paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 96 E1472–E1476. ( 10.1210/jc.2011-1043) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpershoek E, Petri BJ, Post E, van Eijck CH, Oldenburg RA, Belt EJ, de Herder WW, de Krijger RR, Dinjens WN. 2014. Adrenal medullary hyperplasia is a precursor lesion for pheochromocytoma in MEN2 syndrome. Neoplasia 16 868–873. ( 10.1016/j.neo.2014.09.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letouze E, Martinelli C, Loriot C, Burnichon N, Abermil N, Ottolenghi C, Janin M, Menara M, Nguyen AT, Benit P, et al 2013. SDH mutations establish a hypermethylator phenotype in paraganglioma. Cancer Cell 23 739–752. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 1303.3997. (available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997) [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Shiraiwa K, Ko KN, Moon J, Park SH, Lee M, Shin S, Kim M, Jang H, Lee Y, et al 2013. A paraganglioma in the posterior wall of the left atrium originating from the aortic body in a Wistar Hannover rat. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology 65 631–636. ( 10.1016/j.etp.2012.07.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. 2014. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30 923–930. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd R, Osamura R, Klöppel G. & Rosai J. 2017. WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs, 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lussey-Lepoutre C, Hollinshead KE, Ludwig C, Menara M, Morin A, Castro-Vega LJ, Parker SJ, Janin M, Martinelli C, Ottolenghi C, et al 2015. Loss of succinate dehydrogenase activity results in dependency on pyruvate carboxylation for cellular anabolism. Nature Communications 6 8784 ( 10.1038/ncomms9784) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussey-Lepoutre C, Buffet A, Morin A, Goncalves J, Favier J. 2018. Rodent models of pheochromocytoma, parallels in rodent and human tumorigenesis. Cell and Tissue Research 372 379–392. ( 10.1007/s00441-018-2797-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher LJI, Smith EH, Rueter EM, Becker NA, Bida JP, Nelson-Holte M, Palomo JIP, García-Flores P, López-Barneo J, van Deursen J. 2011. Mouse models of human familial paraganglioma. In Pheochromocytoma – A New View of the Old Problem. Ed Martin JF. London, UK: InTech; ( 10.5772/25346) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, et al 2010. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Research 20 1297–1303. ( 10.1101/gr.107524.110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkert S, Martin U. 2018. Targeted gene editing in human pluripotent stem cells using site-specific nucleases. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology 163 169–186. ( 10.1007/10_2017_25) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. 2011. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biology 12 R41 ( 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir A, Vander Heiden MG. 2018. The nutrient environment affects therapy. Science 360 962–963. ( 10.1126/science.aar5986) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscarella P, Bloomston M, Brewer AR, Mahajan A, Frankel WL, Ellison EC, Farrar WB, Weghorst CM, Li J. 2008. Expression of the p16INK4A/Cdkn2a gene is prevalently downregulated in human pheochromocytoma tumor specimens. Gene Expression 14 207–216. ( 10.3727/105221608786883825) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace V, Perentes E, Germann PG. 2002. Pheochromocytomas and ganglioneuromas in the aging rats: morphological and immunohistochemical characterization. Toxicologic Pathology 30 492–500. ( 10.1080/01926230290105668) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y, Lu Y, Caisova V, Liu Y, Bullova P, Huynh TT, Zhou Y, Yu D, Frysak Z, Hartmann I, et al 2018. Targeting NAD(+)/PARP DNA repair pathway as a novel therapeutic approach to SDHB-mutated cluster I pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Clinical Cancer Research 24 3423–3432. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3406) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papathomas TG, Oudijk L, Persu A, Gill AJ, van Nederveen F, Tischler AS, Tissier F, Volante M, Matias-Guiu X, Smid M, et al 2015. SDHB/SDHA immunohistochemistry in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: a multicenter interobserver variation analysis using virtual microscopy: a Multinational Study of the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENS@T). Modern Pathology 28 807–821. ( 10.1038/modpathol.2015.41) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasini B, Stratakis CA. 2009. SDH mutations in tumorigenesis and inherited endocrine tumours: lesson from the phaeochromocytoma-paraganglioma syndromes. Journal of Internal Medicine 266 19–42. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02111.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson CU, von Stedingk K, Bexell D, Merselius M, Braekeveldt N, Gisselsson D, Arsenian-Henriksson M, Pahlman S, Wigerup C. 2017. Neuroblastoma patient-derived xenograft cells cultured in stem-cell promoting medium retain tumorigenic and metastatic capacities but differentiate in serum. Scientific Reports 7 10274 ( 10.1038/s41598-017-09662-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piruat JI, Pintado CO, Ortega-Saenz P, Roche M, Lopez-Barneo J. 2004. The mitochondrial SDHD gene is required for early embryogenesis, and its partial deficiency results in persistent carotid body glomus cell activation with full responsiveness to hypoxia. Molecular and Cellular Biology 24 10933–10940. ( 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10933-10940.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JF, Evinger MJ, Tsokas P, Bedri S, Alroy J, Shahsavari M, Tischler AS. 2000. Pheochromocytoma cell lines from heterozygous neurofibromatosis knockout mice. Cell and Tissue Research 302 309–320. ( 10.1007/s004410000290) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JF, Picard KL, Tischler AS. 2009. RET expression and neuron-like differentiation of pheochromocytoma and normal chromaffin cells. Hormone and Metabolic Research 41 710–714. ( 10.1055/s-0029-1224136) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JF, Pacak K, Tischler AS. 2017. Pathology of human pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma xenografts in NSG mice. Endocrine Pathology 28 2–6. ( 10.1007/s12022-016-9452-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JF, Cochran B, Baleja JD, Sikes HD, Zhang X, Lomakin I, Langford T, Stein KT, Tischler AS. 2018. A unique model for SDH-deficient GIST: an endocrine-related cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer 25 943–954. ( 10.1530/ERC-18-0115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raney BJ, Dreszer TR, Barber GP, Clawson H, Fujita PA, Wang T, Nguyen N, Paten B, Zweig AS, Karolchik D, et al 2014. Track data hubs enable visualization of user-defined genome-wide annotations on the UCSC Genome Browser. Bioinformatics 30 1003–1005. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt637) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter S, Qin N, Pacak K, Eisenhofer G. 2013. Role of hypoxia and HIF2alpha in development of the sympathoadrenal cell lineage and chromaffin cell tumors with distinct catecholamine phenotypic features. Advances in Pharmacology 68 285–317. ( 10.1016/B978-0-12-411512-5.00014-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter S, Peitzsch M, Rapizzi E, Lenders JW, Qin N, de Cubas AA, Schiavi F, Rao JU, Beuschlein F, Quinkler M, et al 2014. Krebs cycle metabolite profiling for identification and stratification of pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas due to succinate dehydrogenase deficiency. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 99 3903–3911. ( 10.1210/jc.2014-2151) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]