Abstract

It is crucial for refugee service providers to understand the family planning knowledge, attitudes, and practices of refugee women following third country resettlement. Using an ethnographic approach rooted in Reproductive Justice, we conducted six focus groups that included 66 resettled Somali and Congolese women in a western United States (US) metropolitan area. We analyzed data using modified grounded theory. Three themes emerged within the family planning domain: (a) concepts of family, (b) fertility management, and (c) unintended pregnancy. We contextualized these themes within existing frameworks for refugee cultural transition under the analytic paradigms of “pronatalism and stable versus evolving family structure” and “active versus passive engagement with family planning.” Provision of just and equitable family planning care to resettled refugee women requires understanding cultural relativism, social determinants of health, and how lived experiences influence family planning conceptualization. We suggest a counseling approach and provider practice recommendations based on our study findings.

Keywords: focus groups, refugees, sexual and reproductive health, Reproductive Justice, family planning, contraception, abortion, fertility, infertility, qualitative

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 68.5 million individuals are currently displaced from their homes due to political conflict, war, and violence (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 2018). In total, 80% of these individuals are women and children who are particularly vulnerable to conflicts in their countries of origin (Busch-Armendariz, Wachter, Heffron, Nsonwu, & Snyder, 2013). The majority of displaced individuals remain within their country of origin’s borders and become “internally displaced persons.” Individuals who cross international borders can apply to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to obtain “refugee status.” The United Nations has identified three durable solutions for refugees including (a) repatriation of the refugee to their country of origin after fear of persecution has abated, (b) local integration into host country to which the refugee initially fled, or (c) third country resettlement to a host country agreeing to allow full integration of the refugee into the host country’s society. Approximately 1.2 million refugee women of reproductive age have undergone third country resettlement to the United States (U.S.). While refugees are often grouped within the larger category of immigrants, refugee lived experiences differentiate them from other migrants. In contrast to other immigrant populations, refugees have often fled war, violence, and/or natural disaster and are commonly survivors of torture including rape (Crosby, 2013; Willard, Rabin, & Lawless, 2014). The refugee resettlement process is highly regulated with unique requirements and involvement of multiple governmental and non-governmental agencies. Refugee women post-resettlement are distinctive when compared to other female immigrants and may require unique approaches to sexual and reproductive health care service provision.

The term sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is broad and encompasses many domains including physical, emotional, mental, and social wellbeing in relation to all aspects of sexuality (Starrs et al., 2018). Our work focuses on the family planning component of SRH. We have chosen to use the term “family planning” as it encompasses not only method selection (i.e., contraception) but also social factors that may affect fertility management decisions such as family structure, trauma history, and displacement. The term is further inclusive of decisions surrounding pregnancy intention and management of unintended or mistimed pregnancy.

Refugee SRH

When refugee populations are compared to host country populations, many areas of health disparity exist. These disparities include decreased utilization of preventive health care services (Haworth, Margalit, Ross, Nepal, & Soliman, 2014; Morrison, Wieland, Cha, Rahman, & Chaudhry, 2012), poor understanding by refugees of health care system access and utilization (Herrel et al., 2004; Pavlish, Noor, & Brandt, 2010), and increased rates of poor perinatal outcomes (Biro & East, 2017; Small et al., 2008). The majority of research regarding post-resettlement refugee SRH focuses on pregnancy with little discussion of family planning (Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Gagnon et al., 2007; Herrel et al., 2004; Lane & Cole, 2013).

There are many gaps in knowledge regarding the family planning needs of refugee women after resettlement to the U.S. Quantitative studies include small sample sizes, comparison of resettled refugee women to non-U.S. host populations, and employment of retrospective methodology. Disparities between refugees and host country populations are often described. For example, a retrospective chart review of 52 refugee women resettled to Toronto, Canada revealed higher unmet contraceptive need among resettled refugees than among native Canadians (Aptekman, Rashid, Wright, & Dunn, 2014). Refugees also differ from other immigrant populations. A retrospective chart review comparing outcomes among refugee women, other migrant women, and native Dutch women found that teen pregnancy, unintended pregnancy, and induced abortion rates were highest among refugee women (Raben & van den Muijsenbergh, 2018). In addition, contraceptive counseling and prescription receipt were lowest among the refugee women, with sub-Saharan African refugee women being the least likely to receive a contraceptive prescription.

Few qualitative studies on family planning in refugees resettled to the U.S. are available. A literature search revealed a single qualitative study evaluating family planning among refugees after resettlement to the U.S. Dhar and colleagues (2017) conducted 14 individual interviews with resettled Bhutanese adolescents. Their analysis indicated that family planning was stigmatized among non-married Bhutanese refugees. As a result, the researchers recommended provision of family planning information outside of community settings in safe, confidential spaces using culturally appropriate language. Qualitative studies of other SRH topics among resettled refugees have focused on perinatal and obstetric care (Jacoby, Lucarelli, Musse, Krishnamurthy, & Salyers, 2015; Wojnar, 2015), conceptualizations of gynecologic care (Mehta et al., 2017), menstrual conceptions and experience (Hawkey, Ussher, Perz, & Metusela, 2017), barriers to access and provision of care (Z. B. Mengesha, Perz, Dune, & Ussher, 2017; Riggs et al., 2012; Woodgate et al., 2017), and disparities in reproductive health care encounters (Gurnah, Khoshnood, Bradley, & Yuan, 2011; Rogers & Earnest, 2015; Svensson, Carlzen, & Agardh, 2017). Although these studies provide ethnographic insight into refugee women’s SRH after resettlement, they do not provide specific information regarding family planning. This information is needed to develop best practices for provision of sexual and reproductive health care to the U.S. resettled refugee populations.

Due to the lack of qualitative studies addressing family planning among refugee women post-resettlement to the U.S., we developed a needs assessment project to evaluate family planning knowledge, attitudes, and practices.

Study Population Backgrounds

We included resettled refugee women from Somalia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C.) in our study as these two refugee groups are found in many large U.S. cities, including the study city. Nearly a third of refugees arriving to the U.S. are African born. Somalia and D.R.C. are the most common sub-Saharan African countries of origin for refugees resettled to the U.S. (UNHCR, 2018). Data regarding refugee resettlement to the U.S. by global region of origin and African country are presented in Table 1. At the time of study design, an influx of Congolese refugee women being resettled to the U.S. was predicted and our team was interested in comparing these new arrivees with an established refugee community to provide greater depth of understanding regarding post-resettlement family planning conceptualization across groups and time.

Table 1.

Number of Refugees Resettled to the U.S. (2000–2018).

| Region of Origin | Number of Refugees Resettled to the U.S. | Percentage of Total Refugees Resettled to the U.S. |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 308,067 | 29 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C.) | 61,643 | |

| Eritrea | 20,304 | |

| Ethiopia | 15,615 | |

| Liberia | 20,869 | |

| Somalia | 103,839 | |

| Sudan | 21,917 | |

| All other African countries | 63,880 | |

| Asia | 216,472 | 21 |

| Europe | 108,064 | 10 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 59,230 | 6 |

| Near East/South Asia | 354,175 | 34 |

| Total | 1,046,008 | 100 |

Source. Refugee Processing Center (U.S. Department of State & Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, 2019).

The post-resettlement period marks an important time of transition for refugees. Understanding how the diverse cultures and experiences of refugee woman shape views on SRH is essential. Refugee views may be influenced by traumatic experiences; for example, prior to displacement, Congolese women are often victims of sexual and domestic violence, have witnessed the death of loved ones, and have given birth to children conceived through rape (Busch-Armendariz et al., 2013). Understanding how these experiences, including rape as a tool of war, influence refugee women’s conceptualized needs for family planning is paramount for provision of acceptable sexual and reproductive health care.

The backgrounds of Somali and Congolese refugees differ with regard to original conflict, displacement experience, and post-resettlement support. Somalia’s ongoing civil war began in 1991 and has resulted in an estimated half million casualties and displacement of over 45% of the population. Somali refugees often resettle as family units, including nuclear families, as well as extended family groups. The majority of resettled Somali refugees are culturally and ethnically homogeneous, have high levels of literacy, and practice Islam. Many Somali refugees spent years in refugee camps prior to resettlement and are comfortable with the concept of receiving acute medical care from established health clinics. Within Somalia, family planning services are rarely available due to the instability of the country overall and minimal infrastructure. Abortion is only legal in Somalia to save the life of the mother. Availability of family planning services in refugee camps in Kenya, where many Somali refugees live prior to resettlement, varies by camp location—some with wide availability, some with minimal availability. Abortion is Kenya is legal when, in the opinion of a trained health care provider, there is a need, in an emergency, to protect the life or health of the mother.

In contrast to Somalia, conflict in D.R.C. started in 1996. The UNHCR designates female refugees from D.R.C. as “women-at-risk” meaning that they have “protection problems particular to their gender” including risks of rape and sexual violence. The majority of resettled Congolese refugees are widowed or unmarried women with children. Congolese refugees are ethnically and culturally diverse. Over two thirds of resettled Congolese refugees are below age 25. Displaced Congolese individuals live in camps, urban centers, or the bush. These settings often provide minimal access to health care. Family planning services are available in non-conflict areas of D.R.C but essentially non-existent in conflict zones. At the time our study was conducted, abortion was only legal in the D.R.C. when done to save the life of a mother. A woman who willingly sought elective abortion was subject to 5 to 10 years of imprisonment, whereas the provider of such an abortion was subject to 5 to 15 years of imprisonment.

Reproductive Justice

A Reproductive Justice framework informs this investigation. Traditional approaches to SRH emphasize the importance of the individual and focus narrowly on distinct components of SRH without integration across disciplines or consideration of social determinants of health (Verbiest, Malin, Drummonds, & Kotelchuck, 2016). Reproductive Justice utilizes intersectional theory to combine reproductive rights with racial and social justice. A Reproductive Justice approach demands that reproductive health care providers acknowledge institutional and systemic dynamics affecting individual SRH (B. Mengesha & current fellows in the Fellowship in Family Planning, 2017). Investigations seeking to understand the SRH of resettled refugees must take into account the societal context of refugee status including predisplacement trauma, gender-based violence, and family structure changes as well as post-resettlement conditions including poverty, racial bias, and structural inequality. Starrs and colleagues (2018) propose an integrated approach to SRH and rights that posits that achievement of SRH relies on the realization of sexual and reproductive rights, which are based on the human rights of all individuals. A guiding principle of our work is the acknowledgment that to provide just and equitable family planning services to resettled refugees we must first understand how they conceptualize post-resettlement family planning and how their lived experiences influence approaches to fertility management.

This article aims to address gaps in the literature regarding refugee women’s family planning knowledge, attitudes, and practices after third country resettlement to the U.S. We situate our findings within existing models of refugee transition, evaluate findings in the context of cultural relativism and Reproductive Justice, and use findings to advocate for practice guidelines that will help clinicians approach family planning discussions with resettled Somali and Congolese refugee women.

Method

Study Context

We developed this study in response to a need identified by refugee community members, resettlement agencies, and health service providers to better understand African refugee women’s conceptualizations regarding SRH after resettlement to the U.S. The project coincided with a postgraduate medical training opportunity for the principal investigator. Community stakeholders and local leaders in refugee health were identified early in the research process through formal and informal discussions with refugee community members, resettlement agency staff, refugee health care providers, refugee service organizations, and researchers at our University who had previously worked with refugee populations. Somali and Congolese community members were crucially involved in study design, recruitment, data collection, and cultural verification of data analysis and interpretation. Great care was taken not to perpetuate an American ethnocentric environment. As one example, multiple Somali community members indicated that the male leader of a local refugee self-management agency would be the preferred contact for resettled Somali refugee women. Although this patriarchal, top-down method went against the initial beliefs of the research team regarding autonomy, female empowerment, and a sense that we should contact the women directly, it was culturally appropriate from the perspective of community members. This man was contacted, agreed to help with the project, and played a critical role in participant recruitment. Throughout this project, we relied heavily on community liaisons to help us interact in socioculturally appropriate ways and to create an environment which facilitated communication and observation while minimizing power discrepancies and cultural incongruities between researchers and participants.

Study Design

We employed an ethnographic approach rooted in Reproductive Justice to conduct this qualitative study as a component of a larger needs assessment project. Using typologies described by Creswell and Plano Clark (2011), we designed an embedded mixed-methods needs assessment. Justifications for mixed methods included triangulation, completeness, and instrument development (Bryman, 2006). We integrated the qualitative and quantitative strands of the project using described principles (Fetters, Curry, & Creswell, 2013).

Multiple types of inquiry were considered for the qualitative strand in the design of this study including in-depth interviews, serial observations through community immersion, and focus groups. We elected to use focus group methodology as cultural leaders advised that focus groups were an ideal approach since women in the communities were used to meeting as a group to discuss health topics and may be “shy” if these sensitive topics were brought up in an individual interview setting. Community members further raised concerns that observation or cultural immersion could be seen as coercive or “spying” based on the lived experiences of refugees prior to displacement. We hoped that focus groups would obtain context-setting community-based data and allow for emergence of issues deemed important by the participants (Culley, Hudson, & Rapport, 2007). As this study was the qualitative strand of a mixed-methods project, we intended to further investigate topics identified through focus groups in the quantitative strand of our project, which included development, and deployment of individual surveys. Evidence demonstrating the ability of focus groups to facilitate access to unheard populations with discussion of sensitive topics (Farquhar, 1999) and to minimize power discrepancies between researchers and participants (Wilkinson, 1999) further strengthened our decision to use this methodology.

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Utah approved the study in April 2014. Of note, we applied to the IRB for a waiver of signed consent due to the possible trauma histories of our participants. In consultation with community members, it became clear that prior to resettlement individuals were often coerced into signing documents that were later used against them in maleficent ways. We were concerned that the requirement of signatures on documents may undermine trust between participants and the research team and/or cause participants to relive prior trauma experiences. We applied for, and were granted, a waiver that allowed us to use verbal consent instead of collecting signatures.

Focus Group Guide Development

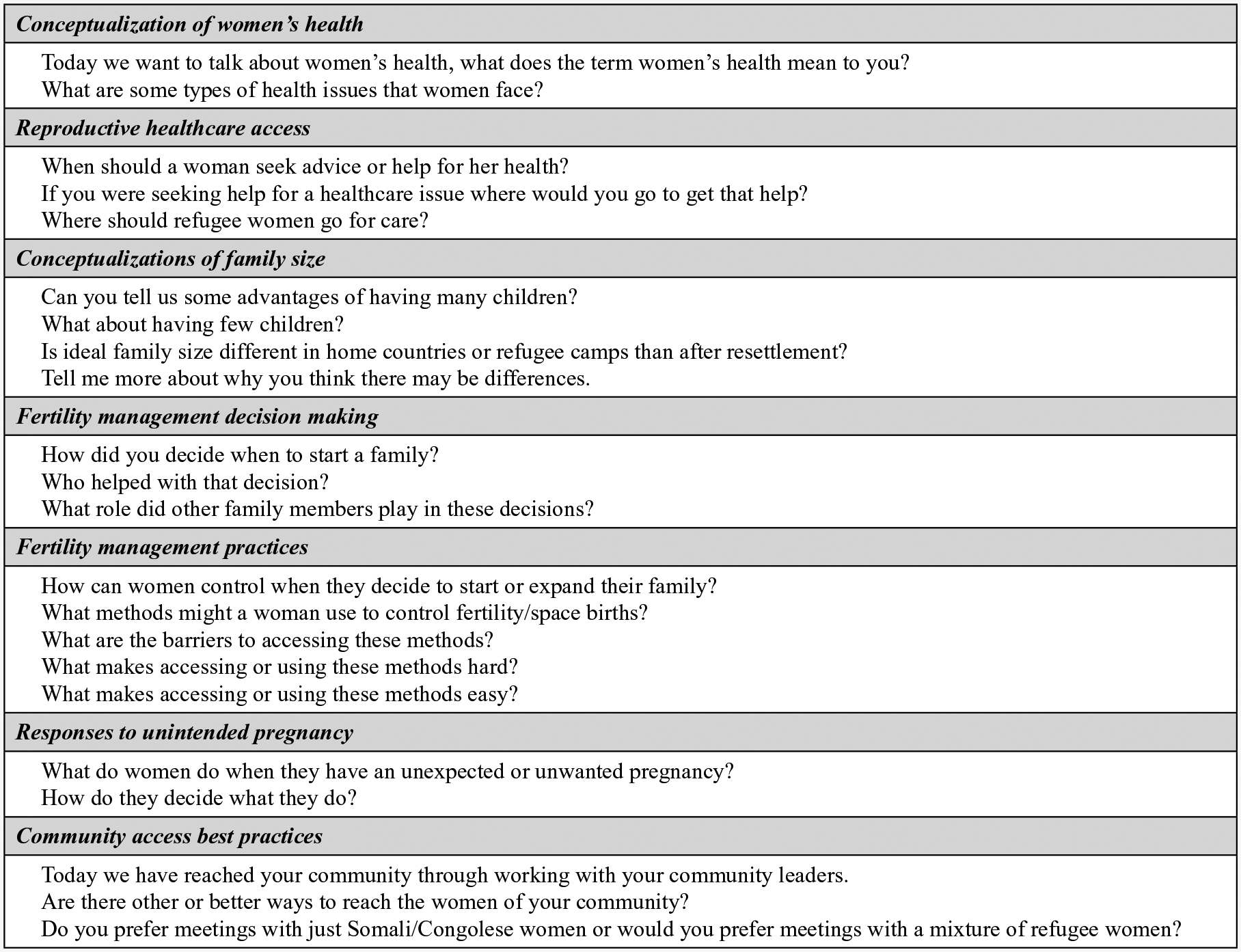

We developed our focus group guide based on a framework outlined by Krueger and Casey (2009). Our aims included exploration of the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of resettled Somali and Congolese women regarding reproductive health concerns, access and barriers to reproductive health care, family planning conceptualization, contraceptive method acceptability, views on unintended pregnancies, and best practices for researchers to maintain community collaboration and access. These areas of interest were identified through conversations between the research team, refugee community members, and local providers of refugee services including health care. Piloting of the focus group guide was undertaken with select community members to ensure cultural appropriateness and understanding. After piloting, the guide was revised to incorporate community feedback. Externally located, certified translators translated and back-translated the focus group guide into Swahili and Somali. The translators adhered to established protocols to ensure translation quality (Sperber, 2004). Translated materials were reviewed with focus group facilitators prior to commencement of the study to ensure appropriate translation. We designed all focus group questions to allow for natural progression of conversation and avoided inclusion of predetermined prompts or leading questions. The focus group guide is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Focus group guide.

Facilitator and Participant Recruitment

We recruited female Somali and Congolese focus group facilitators. These women are well known and trusted within their communities, speak English as well as the target study languages (i.e., Somali or Swahili) and other languages commonly spoken by the refugee populations in our study (i.e., Lingala, Kinyarwandan). The principal investigator conducted individual training sessions with each facilitator reviewing research basics, focus group facilitation techniques, study purpose, and protocols.

We recruited participants through partnership with local community groups via personal communication between women and community group leaders. We informed women who self-identified as members of the resettled Somali or Congolese community about the study either in person or via cell phone contact. If they wished to participate, we told them of meeting times and location. We also employed snowball sampling, encouraging women who agreed to participate to bring interested friends or family members to focus groups. We established a recruitment goal of eight to 10 participants per group.

Focus Group Conduct

We held focus groups in private rooms at community centers and spaces familiar to participants. Each focus group included a meal, free child care, and carpool transportation assistance. At the discretion of cultural leaders, who were concerned about the sensitive nature of our study topic, we only invited women to participate in our focus groups and did not mix Somali and Congolese participants. Each participant received a consent cover letter, in either Swahili or Somali, which reviewed study purpose, procedures, confidentiality protections, and options for women who did not wish to answer questions. Focus group leaders read this letter out loud to participants in native languages prior to beginning the discussion. Potential participants had a chance to ask questions and/or leave if they did not wish to participate; no potential participants chose to leave. Participants were provided with contact information for the principal investigator, who is a physician, and IRB in case any issues arose as a result of study participation. Study staff collected demographic information including age, gravidity, parity, household size, marriage status, resettlement agency, time since resettlement, and countries lived in since displacement via semiprivate verbal interview utilizing facilitators prior to focus group commencement.

We conducted the focus groups in the native language of participants with minimal intragroup translation. Each group began with a review of the importance of confidentiality and discussion of ground rules including everyone being allowed to speak, only one person speaking at time, and the importance of each participant’s opinion. To encourage each participant to speak up, the focus group started with asking each participant to introduce themselves to the group and provide information about an unrelated subject, such as a favorite color, food, or activity. The developed focus group guide was then used to address community beliefs regarding seven areas of reproductive health. We employed audio and video recording of all sessions to aid with translation, transcription, and assessment of verbal and non-verbal cues. The research team created physical maps of focus group seating to aid with speaker identification. Focus groups lasted between 45 and 70 minutes. Each participant received a $25 gift card for participation. Debriefing occurred between the research team and focus group facilitators immediately following every focus group session. The principle investigator, Dr. P.A.R., attended all focus groups. All research team members present at a group took field notes that the study team reviewed during data analysis.

Data Analysis

We utilized modified grounded theory for data analysis (Charmaz, 2014; Creswell, 2009). Grounded theory, as described by Charmaz (2014, 2015), allows for emergence of theory from data without focus on structured or forced frameworks. Our coding strategy employed inductive analysis with codes and themes being content driven and arising from data and participants rather than based on theory or hypothesis.

After each focus group session, externally located, certified translators translated audio recordings and transcribed these verbatim. Study staff then verified each transcript for accuracy while addressing any discrepancies between written transcripts, audio, and video recordings. Two team members (Dr. P.A.R. and Ms. B.J.) initiated line-by-line coding prior to completion of all focus groups. Early initiation of coding allowed evaluation of emerging data with revision of the focus group guide to better assess areas of interest. For example, after the first focus group, we revised the original question, “Can you tell us some advantages of having a big family? What about a small family?” to “Can you tell us some advantages of having many children? What about having few children?” This revision occurred when the research team realized that the refugee groups conceptualized family differently from the researchers and a question regarding family size did not necessarily address family planning practices.

Coding prior to completion of all focus groups allowed for an iterative research process with continual negotiation among the research team as to whether and when saturation was reached. We aimed to achieve not only “code saturation,” defined by Hennink, Kaiser, and Weber (2019) as “the point when no additional issues are identified in the data and the codebook has stabilized,” but also “meaning saturation” defined as “the point at which we fully understand the issues identified and when no further insights or nuances are found.” To assess saturation, our team held debriefing sessions with focus group facilitators, thoroughly interrogated transcripts, reviewed field notes and memos from focus groups, and reviewed video recordings of focus groups. This multimodal approach moved beyond the analysis of verbal communication to include the assessment of non-verbal cues, incorporate feedback from bicultural team members, and achieve a rich data set. Theoretical notes were used throughout the process to record the analytical thinking and reasoning of the research team.

Following preliminary review of data, we developed a coding dictionary. Two of the authors (Dr. P.A.R. and Ms. B.J.) independently coded transcripts using the coding dictionary. Following completion of individual coding, the pair of research team members held reconciliation meetings to merge meaning codes while allowing new meaning units to emerge. We refined the coding dictionary as necessary during the reconciliation process. After reconciliation, a third author (Dr. L.M.O.) reviewed the analytic trail of the research dyad, offering additional interpretation and assisting with inductive restructuring.

The same coding process was completed for all six transcripts. We aggregated data into three original domains and then further subdivided it into themes and subthemes. Data were interrogated to evaluate how themes varied or remained stable within and across refugee groups. Original domain structure allowed for a domain-specific taxonomy, whereas the within-group structure provided understanding of the cultural experience of each group. Once aggregated, data were discussed and consensus negotiated by the research team. We used Atlas.ti software (version 1.0.22 (92)) for data management and analysis.

Results

Saturation

Code saturation in our study was noted after two focus groups with each community, whereas meaning saturation was approached after three focus groups with each community. Our findings that six focus groups were needed to approach complete saturation are consistent with recent literature indicating that multiple focus groups per stratum are required to reach meaning saturation and code saturation is often achieved by six focus groups (Coenen, Stamm, Stucki, & Cieza, 2012; Guest, Namey, & McKenna, 2017; Hennink et al., 2019).

Participants

We conducted three focus groups with resettled Somali (n = 41) and three focus groups with resettled Congolese (n = 25) refugee women between May and August 2014. Group size ranged from seven to 15 participants with an average of 14 per Somali group and nine per Congolese group. Participants were 18 to 68 years old. The groups differed with Somali women being older and resettled for a longer period of time compared to Congolese women. Somali women were also more likely to be currently married and had greater gravidity. Household size was similar between the two groups.

Domains and Themes

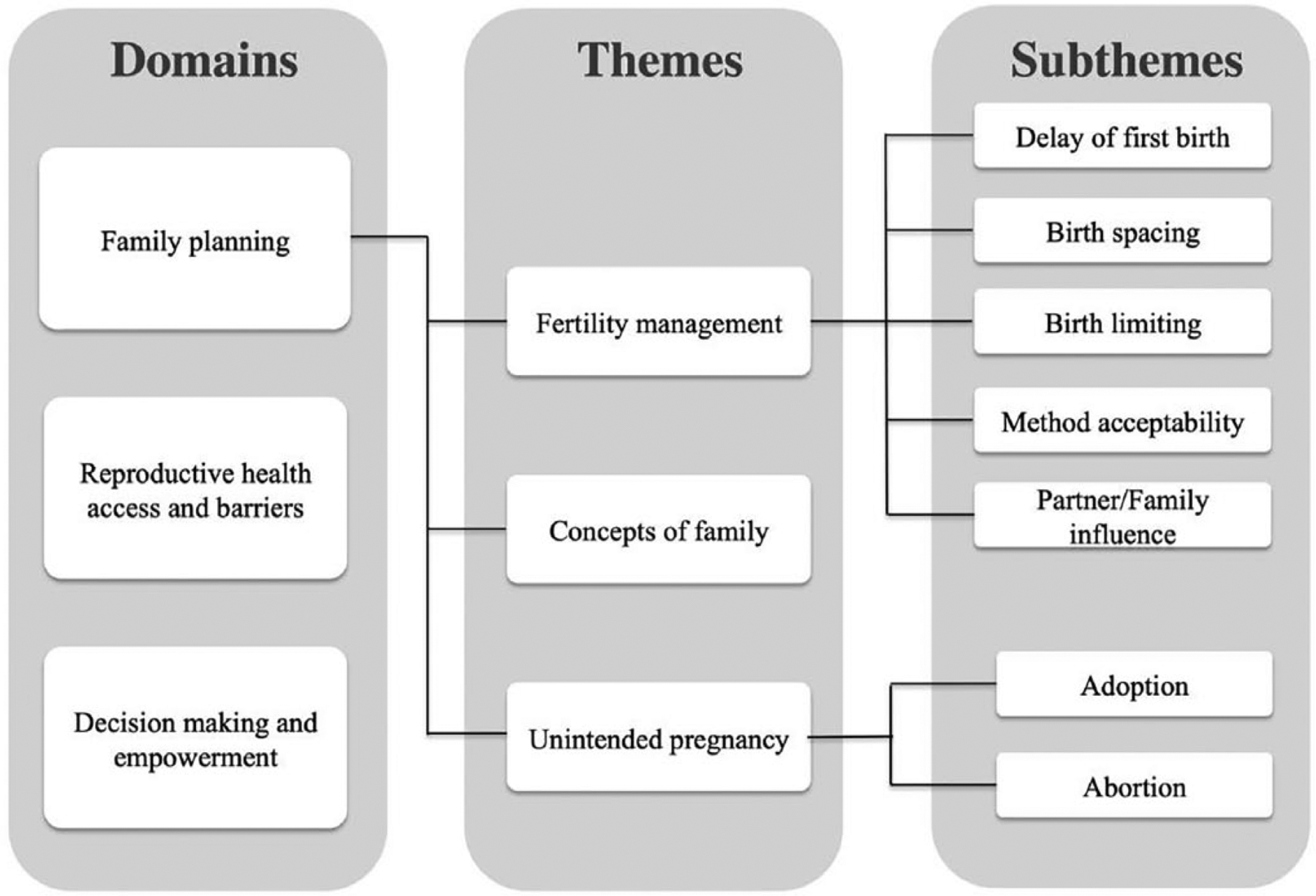

Three domains emerged from the focus groups: (a) reproductive health access and barriers, (b) family planning, and (c) decision-making and empowerment. The results reported here focus on the domain labeled “family planning” and describe the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of resettled Somali and Congolese refugee women. Three themes emerged within the family planning domain including (a) concepts of family, (b) fertility management, and (c) considerations surrounding unintended pregnancy. Analysis of themes revealed components shared by both Somali and Congolese refugee groups while also illuminating the unique ways each group conceptualizes each theme and relates the theme to their perceptions of U.S. conceptualizations. Domains, themes, and subthemes are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Domains, themes, and subthemes.

Theme 1: Concepts of family.

Constructs of family for both groups extended beyond the nuclear family to include multigenerational extended families. A Somali participant noted, “In America, when you hear of family, you think of the woman, her husband and their children and only that, but for us, I think we know family as the extended one.” For Somali women, this concept of family did not depend on resettlement status. As one Somali woman noted, “My family [post-resettlement] comprises of me, my husband and children, but I think more of my extended family members in other countries.” Congolese women also endorsed the concept of family as multigenerational but were more likely to separate concepts of family pre- and post-resettlement making distinctions about family “in Africa” versus “here.” A Congolese woman noted, “Yeah, in Africa big family, but not just your kids. Your brothers and sisters, big family. Extended family, like how you guys call it in America.”

Both groups of women articulated a perceived community preference for many children. Each community cited experiences with high rates of infant and child mortality as an influence on desire for high fecundity. A Somali woman noted, “When you have a lot of kids, some of them will be alive, some of them will be dead. Some will go to God, and He will leave others to you.” A Congolese participant stated, “the problem is, at home [in Africa], we need to have many children, because if you have one or two children and they die there are [no] other children left.”

Somali women further described the desire for many children as rooted in an independently positive view of large families. As one Somali woman explained, “Let’s say, your daughter gives birth to children, your son gets children and you become a grandmother and the children multiply. You become happy with that multiplication of the family.” Somali women also placed significant emphasis on children as a demonstrative blessing from God. As one Somali woman noted, “Many children are essentially good, but all is about the blessing of God.” This perceived blessing was not dependent on the number of children with a Somali participant stating, “First of all … Allah can either bless small number of children or large number of them.”

Congolese women clearly articulated the idea of children as an investment with one Congolese women noting, “when a parent has many children, the parent sees that they will be helped by the children in the future,” and another Congolese woman stating, “when you get sick and can’t work, there are many [children] ready to help the mother.”

Discussions among both Somali and Congolese women focused on the increased difficulty of child rearing after resettlement. Both groups verbalized the loss of traditional, multigenerational family structure as a significant factor impacting their opinions about many versus few children. When discussing raising children in the U.S., a Somali woman stated, “When you give birth here, you can’t take the children to this aunt or that aunt; there is no such thing here.” Congolese women also expressed this sentiment and noted lack of resources and personal isolation as significant factors for changing fertility desires with a Congolese participant stating,

When you start to have kids … here, you’re [on] your own here. You take care for your kids. You’re [the] only one. But in Africa, you have aunties, uncles. Like I go to my auntie. I go to my uncle. They can take care for them [the children]. But here, you have to take them [children] wherever, [whether] you want [or] you don’t want. It’s like this.

Theme 2: Fertility management.

Both Somali and Congolese women highly contextualized family planning concepts with a focus on whether family planning was used for (a) delay of first birth, (b) birth spacing, or (c) limiting of total births. Initially, Somali groups indicated that fertility control was left to the will of God with comments like “becoming pregnant is something that’s left to the will of God.” Further discussion among Somali participants revealed a common sentiment that, in certain circumstances, contraceptive methods could be used for birth spacing but not delay of first birth or limiting of total births. These statements emphasized a perception that birth spacing agreed with the tenets of Islam. Fertility management discussions among Congolese women revealed knowledge of family planning methods and general acceptability of their use for birth spacing and limiting of total births among partnered individuals. Method acceptability and the influence of family or partner on fertility management decisions varied between the two groups.

Subtheme 2a: Delay of first birth.

Somali women did not accept delay of first birth and discussed differences between Somali and U.S. expectations regarding planning prior to first birth. These women related that it was not common in their culture to sit down with a partner and discuss family planning. As one Somali participant noted, “The thing is, you know, the thing is that when Somali people get married … they don’t discuss any plans about pregnancy and children.”

Congolese women also denied use of fertility management to delay first birth. Most women reported the expectation of pregnancy, shortly after marriage. One Congolese woman stated, “Like I think that mostly in Africa, when you get married, the first thing in the marriage is to have babies. So it’s a big deal for the woman to have babies.” Congolese participants noted family expectations as the main reason for not delaying first birth. As one Congolese woman commented, “mostly the husband’s family, they start to complain about how you don’t make babies.”

Subtheme 2b: Birth spacing.

Somali women commonly cited health of the mother and child as justification for birth spacing. One Somali woman noted, “To get many children without family planning is not good for [maternal] health and it is not good for the health of the child either.” Another Somali participant contextualized the importance of birth spacing for maternal health as aligning with Islamic teachings, “Islamic religion allows spacing children for good growth and that is in fact good for mother’s health. You get another child when your child has already grown up and is walking.” Somali women further noted that ideal birth interval depends upon resource availability:

Speaker 1: The children with one-year interval or less interval are not harmful if you have enough resources.

Speaker 2: That is if you have enough resources and you are healthy.

Speaker 3: It is about being healthy. If you are healthy, you can give birth as you want.

Speaker 4: You are supposed to get more children when you are having enough resources.

Congolese participants reported family planning for birth spacing as acceptable but rarely employed. As one Congolese participant noted, “every year you have a child, you are pregnant with a child, one is walking, one is crawling.” Other Congolese participants confirmed this as culturally normative behavior.

Subtheme 2c: Limiting births.

Limiting of birth number was not well accepted in the Somali community. As one Somali woman stated, “we can’t say that we want this many or that many [children]. It’s whatever God gives you.” The women verbalized their perception that this behavior differed from U.S. family planning practices. For example, a Somali participant noted,

When it comes to them [Americans], you know, they sit down together. The husband and wife sit down together and discuss it. They decide that they want two children. And they stick to having two children.

Somali participants identified perceived differences between native Somali and U.S. cultural norms in discussion regarding fecundity. One Somali participant noted, “It seems that you are not supposed to have children here. You are not supposed to have children in America.” This was seen as in direct opposition to Somali practices, with another Somali participant explaining,

While we’re healthy and able to run around, we will work and we will have children. Thank God! Their [American] beliefs and ours are different. They’re not the same. So, thank God! Whatever God gives us, we will welcome.

In contrast, the Congolese women in our focus groups reported acceptance of limiting total births. However, Congolese participants predicated the decision to limit birth on pre-resettlement versus a post-resettlement status. Many Congolese women noted the native cultural norm of not limiting births prior to resettlement with one Congolese woman stating, “Africa, you have babies. Babies.” Post-resettlement there was an acknowledgment of the impact of limited resources on desired number of children. As one Congolese woman noted, “I think … [fewer children] is good. Cause like me, I don’t have anything.”

Subtheme 2d: Method acceptability.

Somali participants grounded family planning method acceptance in alignment of methods with Islamic teachings. Breastfeeding was described as permissible and its use endorsed by many Somali women. As one Somali participant noted, “Islamic Religion permits a mother to breastfeed her baby for two continuous years. You can use breastfeeding as family planning.” Oral contraceptive pills and injections were endorsed as appropriate methods to supplement breastfeeding: “You can use two types of family planning. A mother does not become pregnant unless the baby is weaned. If the mother gets her period while breastfeeding, then she can use an injection or family planning tablets.” Knowledge of injections was associated with being in refugee camps after displacement from Somalia. As one Somali woman noted, “I have seen many women in refugee camps using it.” No Somali women in our focus groups discussed condoms, withdrawal, calendar method, or the implant for birth spacing. The intrauterine device (IUD) was probably referred to by a single Somali participant who noted, “There are also these modern small things which I have never known … young ladies use inserting [into] their bodies.” When asked about where they would go to obtain a modern family planning method, such as pills or injections, Somali women agreed that they would seek care from a doctor.

Congolese women reported knowledge of many methods to prevent pregnancy. Many Congolese participants described acceptance of the calendar method and noted instruction in use of this method prior to displacement. One woman explained, “[we] learn in school how to calculate. You know, the dates to not get pregnant.” Congolese women demonstrated sophisticated and nuanced knowledge of the calendar method with the ability to discuss cycle variation between and among individuals. Congolese women also mentioned breastfeeding as a method for birth spacing with one woman noting, “in the past, in the times of our mothers, they would give birth every two years, they would breastfeed a lot. Until the baby pushes it [the child] off [the breast].” Controversy arose among Congolese participants when discussing abstinence as a method for spacing births. One Congolese woman noted, “So when you have a baby, like you would wait a year, a year and a half [to have sex].” In response to this statement, another Congolese woman reported that abstinence did not work due to partners noting, “The men don’t accept it [abstinence].” Partner acceptance was also a concern regarding condom use with statements like “Congolese [men] do not like condoms.” Multiple Congolese women in different focus groups knew about or reported use of injections. As one Congolese woman noted, “I really like the vaccine, and want it now.” Congolese women also mentioned knowledge of contraceptive pills or “medicine” as a method for birth spacing although no women in our groups reported actual use of oral contraceptives. No Congolese women in our focus groups discussed the implant as a contraceptive method. At least one woman in each Congolese focus group had knowledge of the IUD, which they referred to by name or described as a device placed inside a woman while pointing to their lower abdomen/pelvis. When an individual woman would mention IUD use, the other women in the group asked many questions regarding placement, side effects, method of action, and obtainment. Universally, the Congolese focus group participant who had mentioned the IUD did not know the answers and deferred questions to study personnel.

Although Congolese women reported an attitude of openness toward use of many different types of contraceptives, they were deferential in articulation of why one method would be preferred over another. Referring to the principal investigator, who was present for all focus groups, one Congolese woman noted, “Now it is her to tell us which one is good?” When asked about where they would go to obtain modern family planning methods, Congolese women reported that they did not know where to obtain contraception.

Subtheme 2e: Partner/Family influence.

While Somali participants reported not discussing family planning with partners or family, Congolese women noted the significance of partnership in family planning. Many Congolese women reported no use of family planning methods post-resettlement because they were not partnered. Discussion of predisplacement practices focused on family planning as taking place between a woman and her husband. Traditional gender roles were important with a general consensus that, particularly prior to resettlement, the man had the final decision about family planning. Statements such as “you can have a number, but your husband doesn’t agree” and “yeah, so the guy decides” were used to illustrate the patriarchal nature of family planning among Congolese couples. Congolese women reported fears of infidelity and abandonment if they challenged the man’s decision. When discussing obtaining contraception prior to resettlement, one Congolese woman noted, “If you ask him he won’t agree, he may not want it … [get contraception] by yourself and he may tell you to go back to your parents.” A difference in gender relations and the subservient role of Congolese women pre- versus post-resettlement was articulated by a young Congolese woman, who resettled to the U.S. as an adolescent,

I feel like in Africa, they [men] have control over women. Like women don’t like have power, over like their lives. Once they get married, it’s like the men have to do everything, have a say about what happens to your life.

Another Congolese woman explained,

Most of time, in Africa, the man is the chief in the house. He’s the one who decides everything. … I know my ex-husband, his brother, the woman wants to have like more than two kids. But the husband says “sorry, I can’t have more than two kids, because I’m raising my brother’s kids ….” So they can’t have more than that because the husband decides.

Post-resettlement, Congolese women reported more equal relationships. Reflecting on this change in gender relations, a Congolese woman noted, “And since now, women going to school … now it’s kind of changed … because sometimes in the relationship, the husband [accepts a more] open marriage, like [one] that the woman can say anything.” Summarizing a discussion on gender roles, which evolved from a contraceptive decision-making question, another Congolese woman noted that after resettlement “He [the partner] will tell you that this America is yours.”

Theme 3: Concepts surrounding unintended pregnancy.

Somali women universally described pregnancy as a blessing from God. Somali participants in our focus groups did not engage with the concept of unintended pregnancy. Congolese women explicitly acknowledged the concept of unintended pregnancy and engaged in discussion of options for when unintended pregnancy occurred.

Subtheme 3a: Adoption.

For Somali women, implicit acknowledgment of unintended pregnancy surrounded discussion of familial adoption with statements like, “If the child born to you is supposed to be a secret and you have to move in with your husband, you give the child to others in your family, your sister, your aunt and so on.” Somali participants accepted familial adoption and described it as happening, “A lot. And even, for example, if your sister doesn’t have a baby, you can give the baby to her.” Somali women did not accept the concept of non-familial adoption.

Congolese conceptualizations regarding adoption placed significance on the reason for adoption. Initial queries regarding adoption were met with strong opposition to the practice with participants noting, “we don’t do adoption,” “in our country no,” and “I better suffer with my kid.” Congolese women’s opposition to adoption focused on the idea of maternal–child bond. As one Congolese woman noted, “if you give the baby away I don’t think the affection of the mother and child will be the same.” With further questioning, exceptions to opposition to adoption became apparent. Many Congolese women agreed with the statement by one participant that, “In your family, you can take it from your family, can adopt.” Another Congolese woman pointed out that maternal mortality represented a time that adoption was widely accepted noting, “It depend[s] sometimes you can give your child to be adopted in example the mum was having baby and she pass away. That [is a] time, that pain, that’s when they will do adoption.”

Subtheme 3b: Abortion.

For Somali women, the ending of a pregnancy was described as up to the will of God. One Somali woman explained the only way to terminate a pregnancy was “if God causes a miscarriage in you.” The only mention of abortion in any Somali focus groups was one Somali woman’s assertion, “we don’t even know anything about abortion.”

Congolese opinions regarding abortion were mixed. One Congolese participant noted, “some people have the abortion and some keep the baby.” Religious beliefs underpinned objections to abortion among Congolese participants as exemplified by statements including, “it’s a sin, and you need to come before God and repent.” Another Congolese participant identified the concept of children as investment as a rationale against abortion noting, “…sometimes you don’t know what that child would have been like. They could have helped you with things more than anybody else.” Prior to resettlement, Congolese women reported that abortions were performed in homes using traditional medicines. These practices were related to inability to receive termination of pregnancy from providers in hospitals or clinics. As one Congolese woman relayed, “… back in Africa, even if you go to a doctor and tell them that you don’t have a husband, they don’t do anything and you will have to go through the problem alone.” This was contrasted with the availability of abortion post-resettlement with a Congolese participant stating, “Here in America, is better because you can go to hospital and say that you are not ready to give birth, and you can ask for an abortion. But at home, it’s seen as very bad to have an abortion.” Neither group of women acknowledged or discussed the complex sociopolitical climate surrounding abortion in the U.S.

Discussion

Our study findings provide insights regarding family planning knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Somali and Congolese refugee women after resettlement to the U.S. We identified three themes as crucially informing family planning conceptualizations among these women: (a) concepts of family, (b) fertility management, and (c) concepts surrounding unintended pregnancy. The degree to which each of these themes impacted each refugee group and specific family planning strategies varied. Analysis of our data led to the development of two paradigms: (a) pronatalism and stable versus evolving family structure and (b) active versus passive engagement with family planning. Our data highlight commonalities as well as differences between resettled Somali and Congolese refugee women. The findings of this study provide a framework for refugee health providers as they approach family planning discussions with resettled refugee women.

Pronatalism and Stable Versus Evolving Parenting Structure

Within the theme “concepts of family,” women in our study reported strong preferences for many children. These preferences were rooted in concerns about child mortality and the belief that children were an investment that may ensure future security. Both Somali and Congolese participants reported large family size as important in the setting of extended, multigenerational families who shared the burdens of parenting. Displacement and the resettlement process often led to dissolution of this traditional family structure but did not always lead to a difference in the way family was conceptualized. Somali women continued to conceptualize family as the extended family regardless of resettlement status. Congolese women frequently reported the concept of multigenerational families prior to displacement but referred to post-resettlement families as consisting of them plus their children.

Rousseau, Rufagari, Bagilishya, and Measham (2004) describe three strategies refugee families can use to cope with the loss and transformations of displacement and resettlement: (a) integration of native cultural anchors into the new realities of life in the host country, (b) self-permanence as an anchor with liabilities from new cultural practices placed on outside entities, and (c) focus on loss—past, present, and presumed future—as a constant anchor. These authors note that families who fall into the first category are more likely to incorporate receiving country sociocultural norms and undertake negotiation of native country gender roles and responsibilities. The Congolese participants in our study predominantly fell within this first category. Congolese participants identified an association between resource limitation post-resettlement and changes in consideration of family planning. In contrast, Somali participants in our study consistently aligned with Rousseau’s second category. Somali women often grounded their observations regarding family planning in “us versus them” language and focused on the importance of ensuring family planning agreed with religious teachings. Our findings are consistent with those found by Degni, Koivusilta, and Ojanlatva (2006) who note that women of Somali descent living in Finland have low contraceptive use and strong pronatalist attitudes rooted in their religious beliefs.

Our data regarding Congolese women’s evolving views regarding family planning are further informed by Baird’s (2012) theory of refugee women experiencing cultural transition. In this model, refugee wellbeing is defined as “a process measured over time in which one has adequate resources to meet basic physical, social and spiritual needs.” Wellbeing is enhanced as refugee women achieve autonomy, social contacts, skill mastery, and hope. Wellbeing is decreased by dependency, isolation, lack of skills, and hopelessness. Congolese women in our study underwent transition from a predisplacement paternalistic society, where their male partners made decisions, to post-resettlement as unpartnered women making their own decisions. With the loss of native family structure, read-dressing gender roles may encourage resettled refugee women to self-actualize and achieve autonomy. As resettled Congolese refugee women navigate being unpartnered in a new country and develop self-agency, it is likely that their approach to family planning will continue to evolve.

Discussion of family planning with post-resettlement refugee women should include the assessment of family structure and parenting responsibilities. As refugee women adapt to life in the U.S., fertility desires may change in response to decreased child mortality, increased parenting burdens, and alterations in material and human resources. These changes must be incorporated into a contextually appropriate evaluation of family planning needs.

Active Versus Passive Engagement With Family Planning

Within the theme of “family planning,” Somali and Congolese women in our study reflected on their cultural identity as mothers and partners. Motherhood was considered an important first step in solidifying a marriage for both groups and delay of first birth was not routinely practiced after marriage. Participants generated little discussion regarding delay of birth prior to marriage; the few mentions of premarital birth occurred during discussion of unintended pregnancy and revealed community practices of familial adoption.

Somali women viewed birth spacing as culturally appropriate when necessary for health of the mother or in low-resource settings. These women contextualized family planning in religion with the sentiment that ultimate decisions are left to the will of God. Somali participants situate method choice in a religious context with the belief that modern contraceptive methods should be used only as an adjunct to the traditional method of lactational amenorrhea. Interestingly, although Somali women often referred to the importance of “Islamic tenets,” they did not elaborate regarding what these tenets were or whether they were derived from the Quran, Mosques, Imams, or elsewhere.

Congolese women expressed less engagement with the concept of birth spacing. They rooted concepts of birth spacing in a native sociocultural norm of having babies every year. Congolese women were accepting of a diverse contraceptive method mix but less actively engaged with consideration why one method would be preferred over another.

Active versus passive engagement with concepts of reproductive health and family planning influenced each group of women’s approach to fertility management. Somali women actively engaged with the concept of fertility management by articulating an awareness of U.S. sociocultural norms regarding family planning while also demonstrating a conscious decision to maintain native Somali sociocultural norms. These native norms include delay of first birth until marriage, birth spacing for maternal health or lack of resources, and not limiting total births. This behavior of acknowledgment and rejection of host country norms may reflect the effects of an established, resettled community where others support native norms and strongly held religious beliefs. Interestingly, the values and beliefs surrounding fertility management relayed by Somali participants in our study are similar to values reported in work evaluating family planning knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Somali refugees in refugee camps in Kenya (Kiura, 2014). This indicates that these values are stable and anchored over time. In contrast, Congolese women in our study passively engaged with concepts of fertility management. They report knowledge of and openness to use of many methods but defer decisions about which methods are best or reasons for method use to outside authority figures. This may reflect the recency of Congolese resettlement and relative loss of personal autonomy during the displacement and resettlement periods. In addition, the shift from a predisplacement paternalistic society where men made decisions to post-resettlement as unpartnered women may also account for this relative lack of engagement.

Our findings regarding health engagement are further informed by Baird’s (2012) refugee women experiencing cultural transition model which defines three phases to cultural transition: (a) separation—including displacement from country and culture of identity, (b) liminality—an in-between phase where the individual belongs neither fully to their native nor receiving society, and (c) integration— including external components of adaptation to a new environment and internal components of adoption of sociocultural components of the host society. Transition across the phases is described as dynamic and gradual. The majority of Somali women in our study seem to be in the integration phase with adaptation to the receiving country environment, mastery of tasks for survival, and incorporation of desired cultural aspects of their host environment. This phase of transition is associated with increased well-being. In contrast, the majority of Congolese women in our study seem rooted in the liminal phase of transition. This may reflect the effects of a nascent community and relative loss of personal autonomy during the separation phase including displacement and resettlement periods.

Another consideration may be hierarchy of needs post-resettlement. A wealth of data from immigration studies indicate that migrant’s immediate focus during resettlement is often on meeting basic living needs such as housing, food, and employment. Only after these basic needs have been met may individuals then move toward addressing higher level needs such as SRH (Keygnaert, Vettenburg, Roelens, & Temmerman, 2014). These trends are also seen among refugee populations after resettlement. Metusela et al. (2017) conducted in-depth interviews and focus groups with refugee women in Australia and Canada and found that these women often assigned low priority to SRH. Studies of newly arrived refugee youth in Australia further revealed that meeting practical and social needs such as education, language skills, and employment often take precedence over health needs, particularly accessing sexual health services (McMichael & Gifford, 2010). Our interpretation of behavior by Congolese refugee women as passive engagement may also reflect a focus on meeting needs perceived as more pressing by this newly resettled community. Conversely, the well-established Somali community may be further along the continuum of having needs met and thus be able to engage with “higher order” subjects such as SRH.

Providers need to be aware of active versus passive engagement when discussing family planning with resettled Somali and Congolese refugees. Recognition of the decision of Somali women to maintain a pronatalist cultural identity is important, as is working with Congolese women to self-actualize and engage with the definition of their cultural preferences. It is further incumbent upon providers to recognize that early in the resettlement process refugee women may not be ready to engage in SRH discussions as they strive to meet basic economic and social needs. Family planning discussions and education should occur with these principles in mind.

Findings in Context: Cultural Relativism, Sexual Embodiment, and Research as Advocacy

Results of cross-cultural research cannot be viewed in isolation. While our research team involved community members in all aspects of study design, implementation, and interpretation, data analysis was primarily undertaken by White, culturally American, female researchers. Cultural relativism posits that an individual’s values and practices must be viewed through the lens of their culture and not judged based on the values of another culture. As migrants resettle in new locales, there is often an interplay between the integration of receiving country sociocultural practices and the retention of native sociocultural practices (Baird, 2012; Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010; Torres & Cernada, 2003). With cultural relativism in mind, we must acknowledge that the family planning knowledge, conceptualization, and practices of the women in our study are rooted in native sociocultural contexts where talking about sexual health is taboo, patriarchal structure and traditional gender roles dominate provision of SRH, and female sexual empowerment is often limited (Meldrum, Liamputtong, & Wollersheim, 2016; Metusela et al., 2017; Ngum Chi Watts, Liamputtong, & Carolan, 2014; Ussher et al., 2017).

In their work to understand refugee and migrant women’s constructions of female sexual health, Ussher and colleagues note that shame is identified as the dominant cultural and religious construct of female sexual embodiment. This construct of shame is associated with secrecy and silence and rooted in native sociocultural norms that position the ideal woman as “silent in relation to sexual embodiment, lacking in sexual knowledge and experience prior to marriage and passive and receptive in relation to heterosexual marital sex” (Ussher et al., 2017, p. 1915). With transnational migration, these constructs may be challenged by host country sociocultural paradigms. In our study, Somali participants demonstrated this interplay between native and receiving sociocultural norms by involving a male community leader in study recruitment. Prior to the involvement of the male leader, women were hesitant to organize groups discussing SRH. After the involvement of the leader, and with his implicit approval of the project, Somali women actively participated in the study.

Many women in the Ussher study adopted a human-rights-based approach to sexual health after resettlement that allowed them to resist traditional constructs and negotiate sexual agency. The women’s ability to undertake this transformation was strengthened by host countries having stronger legal frameworks to resist sexual violence and access to SRH services promoting agency. Ussher and colleagues note the importance of an intersectional approach to provision of care that acknowledges the structural inequalities and imbalances of power influencing a woman’s SRH. This fits with a Reproductive Justice framework and implies that researchers and providers should advocate for marginalized populations.

Guerin, Allotey, Hussein Elmi, and Baho (2006) use their work on female genital cutting among resettled refugee women in Oceania to illustrate how research can inform advocacy. These authors note the dual researcher-as-advocate role necessary to help refugee women take control of their reproductive health needs. While our White, culturally American, research team does not have the lived experience to fully comprehend how the refugee resettlement process affects conceptualizations of SRH, we do have lived experiences with the U.S. system of SRH provision and family planning. Within a framework of Reproductive Justice and in the context of advocacy, refugee health care providers need to develop culturally appropriate approaches to sexual and reproductive health care provision that are intersectional in nature and account for the confluence of culture, gender, class, ethnicity, and trauma experiences of resettled refugee women (McMorrow & Saksena, 2017; Metusela et al., 2017). We have developed some practice recommendations toward this end.

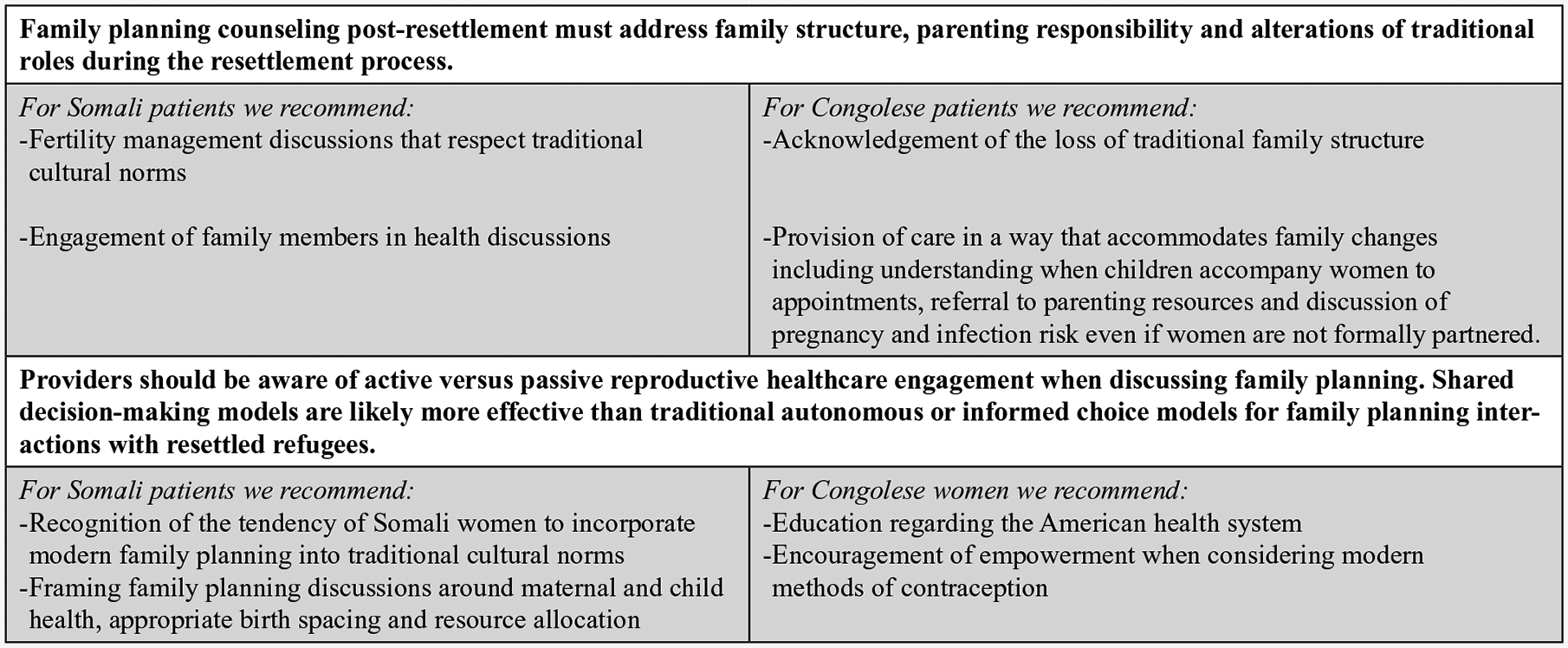

Practice Implications

Many health care providers report feeling ill prepared to provide care to resettled refugees (Lazar, Johnson-Agbakwu, Davis, & Shipp, 2013; Z. B. Mengesha, Perz, Dune, & Ussher, 2018). Providers cite language, time constraints, and limited knowledge as specific barriers to providing care for refugees and immigrants (Alpern, Davey, & Song, 2016; Lazar et al., 2013; Z. B. Mengesha et al., 2018). Meanwhile, refugee women report not seeking care due to a mismatch between their expectations and those of providers (McMorrow & Saksena, 2017; Mehta et al., 2017).

Given these barriers, it is important to consider the optimal method for approaching family planning discussions with resettled refugee women. Within a Reproductive Justice framework, shared decision-making offers an ideal approach that respects cultural preferences while offering empowerment to women. Shared decision-making models, as outlined by Charles, Gafni, and Whelan (1997) describe three phases of decision-making: (a) information sharing, (b) consensus building, and (c) decision-making. Family planning shared decision-making models mitigate the tension between autonomous or informed choice, which places the onus of decision solely on the patient, and directive counseling during which the provider encourages the use of one method over another. A qualitative investigation of an ethnically diverse population of women, both English and non-English speaking, revealed that provider involvement in family planning decision-making processes through a shared decision-making model is well accepted by patients (Dehlendorf, Levy, Kelley, Grumbach, & Steinauer, 2013). Understanding culturally normative behavior and social determinants of health is paramount to a Reproductive-Justice-based approach to family planning provision for resettled refugee women. As part of a shared decision-making model, data from the themes “concepts of family” and “fertility management” indicate that family planning discussions with resettled refugee women should include review of partnership and family structure, parenting burdens, maternal health, and resource availability. We have used the findings from our project to develop broad practice recommendations, which are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Practice recommendations for family planning discussions with resettled refugee women.

Strengths and Limitations

A primary strength of our work is the novel investigation of an understudied area of health for a large group of women living in the U.S. Previous research regarding family planning among resettled refugee women is limited. This investigation into culturally normative behavior surrounding family planning fills a significant knowledge gap.

Another strength in our work lies in the development of robust community partnerships that utilized community member input at all stages of the research process. These partnerships are paramount to our future work. While we worked to engage with communities, we acknowledge that our recruitment strategy relied on community leaders and organizations and can be considered a “top-down” approach. This is a clear weakness that may have introduced selection bias. We hope to use connections with individual women developed through this project to pursue more grassroots projects in the future.

Focus group methodology contributes both strength and weakness to our conclusions. This methodology allowed us to obtain context-setting, community-based data, discuss sensitive topics, and minimize power discrepancies between researchers and participants. However, there is the possibility that contrary opinions were limited by participant concerns about bringing up differing viewpoints. In addition, while focus group methodology provides individual perceptions regarding community-wide approaches to family planning, we did not assess individual conceptualizations in depth. We acknowledge that data from this qualitative project are limited to group perceptions. Our team hopes address individual metrics regarding post-resettlement family planning through other components of our larger mixed-methods project.

Our study is further limited by the inclusion of only two groups of refugee women resettled to a single geographic location. The methodology successfully utilized here could certainly be applied to future endeavors with other communities, but our findings are likely not generalizable to other refugee groups. In addition, our study included only women. A more nuanced and complete understanding of community approaches to family planning could be achieved through the inclusion of male participants. This is clearly an area for further investigation. Finally, the reliance on translation throughout the study may have introduced interpretive limitations to our study.

Conclusion

This work addresses a significant gap in the literature regarding SRH of refugee women resettled to the U.S. Our findings highlight the complex interaction between conceptualizations of family planning and fertility management practices as refugees move along the continuum from displacement to post-resettlement. Refugee manifestations of family planning knowledge, attitudes, and practices involve a balance between retention of native cultural anchors and incorporation of host country culture. This balance is affected by individual as well as societal characteristics and events. Approaching the significant topic of family planning with resettled refugees should take into account the complexities of the refugee lived experience. Shared decision-making models should be used to address family planning with resettled refugee women. Providers must acknowledge evolving family structure, parenting responsibilities, and gender roles while also addressing active versus passive health engagement.

Acknowledgments

We thank our community champions and focus group facilitators for their invaluable assistance with this project: Halima Houssein, Antoinette Uwnaygira, and Abdirzak Ibrahim. Much gratitude is also owed to the community organizations and partners that allowed facilitation of this work: Somali Community Self Management Agency, United African Women for Hope, and Sorenson Community Center.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Society of Family Planning (Grant SFP14-10). Team members receive support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and the Office of Research on Women’s Health of the National Institute of Health, Dr. Sanders via Award K12HD085852, and Dr. Turok via Award K24HD087436.

Author Biographies

Pamela A. Royer is a practicing ObGyn physician providing care for underserved, immigrant and minority women. She holds an adjunct faculty appointment at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

Lenora M. Olson is a professor at the University of Utah Department of Pediatrics, Division of Critical Care in Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

Brandi Jackson is the former director of nursing at Metro Clinic of Planned Parenthood of Utah. She is currently an emergency room nurse at Renown Regional Medical Center, a level 2 trauma center in Reno, Nevada, USA.

Lana S. Weber psychiatry resident physician at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, Oregon, USA.

Lori Gawron is an assistant professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Utah and Gynecology section chief at the Salt Lake City Veterans Healthcare Administration Medical Center in Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

Jessica N. Sanders is an assistant professor in Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Director of Research for the Family Planning Division at the University of Utah School of Medicine in Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

David K. Turok is the Family Planning Division Director in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alpern JD, Davey CS, & Song J (2016). Perceived barriers to success for resident physicians interested in immigrant and refugee health. BMC Medical Education, 16, Article 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aptekman M, Rashid M, Wright V, & Dunn S (2014). Unmet contraceptive needs among refugees. Canadian Family Physician, 60(12), e613–e619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird MB (2012). Well-being in refugee women experiencing cultural transition. Advances in Nursing Science, 35, 249–263. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e31826260c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro MA, & East C (2017). Poorer detection rates of severe fetal growth restriction in women of likely refugee background: A case for re-focusing pregnancy care. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 57, 186–192. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryman A (2006). Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research, 6, 97–113. doi: 10.1177/1468794106058877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bulman KH, & McCourt C (2002). Somali refugee women’s experiences of maternity care in west London: A case study. Critical Public Health, 12, 365–380. doi: 10.1080/0958159021000029568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busch-Armendariz N, Wachter K, Heffron L, Nsonwu M, & Snyder S (2013). The continuity of risk: A three-city study of Congolese women-at-risk resettled in the U.S. Austin: Institute on Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault, The University of Texas at Austin. [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Gafni A, & Whelan T (1997). Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science & Medicine, 44, 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2015). Teaching theory construction with initial grounded theory tools: A reflection on lessons and learning. Qualitative Health Research, 25, 1610–1622. doi: 10.1177/1049732315613982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenen M, Stamm TA, Stucki G, & Cieza A (2012). Individual interviews and focus groups in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A comparison of two qualitative methods. Quality of Life Research, 21, 359–370. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9943-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Plano Clark VL (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby SS (2013). Primary care management of non-English-speaking refugees who have experienced trauma: A clinical review. Journal of the American Medical Association, 310, 519–528. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culley L, Hudson N, & Rapport F (2007). Using focus groups with minority ethnic communities: Researching infertility in British South Asian communities. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 102–112. doi: 10.1177/1049732306296506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degni F, Koivusilta L, & Ojanlatva A (2006). Attitudes towards and perceptions about contraceptive use among married refugee women of Somali descent living in Finland. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 11, 190–196. doi: 10.1080/13625180600557605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlendorf C, Levy K, Kelley A, Grumbach K, & Steinauer J (2013). Women’s preferences for contraceptive counseling and decision making. Contraception, 88, 250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar CP, Kaflay D, Dowshen N, Miller VA, Ginsburg KR, Barg FK, & Yun K (2017). Attitudes and beliefs pertaining to sexual and reproductive health among unmarried, female Bhutanese refugee youth in Philadelphia. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61, 791–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar C (1999). Are focus groups suitable for “sensitive” topics In Barbour R (Ed.), Developing focus group research: Politics, theory and practice (pp. 47–63). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fetters MD, Curry LA, & Creswell JW (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6 Pt. 2), 2134–2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon AJ, Dougherty G, Platt RW, Wahoush O, George A, Stanger E, … Stewart DE (2007). Refugee and refugee-claimant women and infants post-birth: Migration histories as a predictor of Canadian health system response to needs. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 98, 287–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin PB, Allotey P, Hussein Elmi F, & Baho S (2006). Advocacy as a means to an end: Assisting refugee women to take control of their reproductive health needs. Women & Health, 43, 7–25. doi: 10.1300/J013v43n04_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Namey E, & McKenna K (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprob-ability sample sizes. Field Methods, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gurnah K, Khoshnood K, Bradley E, & Yuan C (2011). Lost in translation: Reproductive health care experiences of Somali Bantu women in Hartford, Connecticut. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 56, 340–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00028.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey AJ, Ussher JM, Perz J, & Metusela C (2017). Experiences and constructions of menarche and menstruation among migrant and refugee women. Qualitative Health Research, 27, 1473–1490. doi: 10.1177/1049732316672639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth RJ, Margalit R, Ross C, Nepal T, & Soliman AS (2014). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices for cervical cancer screening among the Bhutanese refugee community in Omaha, Nebraska. Journal of Community Health, 39, 872–878. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9906-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, & Weber MB (2019). What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qualitative Health Research, 29, 1483–1496. doi: 10.1177/1049732318821692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrel N, Olevitch L, DuBois DK, Terry P, Thorp D, Kind E, & Said A (2004). Somali refugee women speak out about their needs for care during pregnancy and delivery. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 49, 345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]