Abstract

Much research associated with mindful eating pertains to weight loss, so this review is novel in that it explores mindful eating in a broader context of it attenuating the widespread problem of chronic stress disturbing gastrointestinal function. This attenuation is rooted in stress offsetting biological homeostasis and mindfulness being a widely studied stress-reduction intervention due to its ability to promote parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) dominance. The stress-digestion-mindfulness triad is a hypothesized construct, integrating what is understood about the digestive system with literature about the nervous system, neuro-endocrine-immune signaling, stress, and mindfulness. Thus, the plausibility of mind-body practices (e.g., mindful eating), which maintain PSNS dominance, helping to cultivate autonomic nervous system (ANS) homeostasis vital for optimal digestive function is established. The clinical utility of the stress-digestion-mindfulness triad involves a clinician-friendly application of mindful eating to improve digestive function.

The Stress-Digestion Connection

Stress is related to functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)1 and functional dyspepsia.2 Notably, FGID severity is proportional to the use of healthcare resources3 and decreased quality of life.4 UK and Canada with equal demographic proportions across countries. Questions included the Rome IV diagnostic questionnaire, demographics, medication, somatization, quality of life, and organic gastrointestinal (GI Given the prevalence of stress in America, stress-reduction interventions are prudent for minimizing FGIDs.

Impacting biological homeostasis, stress is the juncture at which mindfulness can be narrowed into the construct of mindful eating. This vantage point illuminates the role of mindful eating in optimizing digestive function. Stress may result from real or perceived threats that are contextualized as positive or negative. While colloquial conversation is rife with references to psychosocial stressors, sources of stress vary—e.g., stress may be physical (e.g. manual labor, sleep deprivation, extreme exertion), chemical (e.g. alcohol, drugs, pesticides, pollutants), mental (e.g. anxiety, worry, long work hours), emotional (e.g. anger, fear, sadness), and nutritional (e.g. food allergies, micronutrient deficiencies).

Stress often carries a negative connotation, but it is purposeful during life-threatening situations or conditions that require provocation. This involves evaluating stressors and responding to them with physiological resilience via mobilization of metabolic resources needed for the “fight-or-flight” response. Two functions comprise the stress response: (1) surveillance, which assesses internal and external threats, and (2) effector, which mobilizes metabolic resources needed to respond to the threat. Metabolic reserve—the ability of organ systems and tissues to maintain integrity for physiological resilience during stress—safeguards against poor health outcomes that could result from the abrupt physiological changes that characterize the stress response. However, chronic stress may impair metabolic reserve.5 The body is designed to return to homeostasis following acute stress, but chronic stress is problematic. It impairs homeostasis, prevents positive behavioral changes, and contributes to chronic disease6 and gastrointestinal issues.7

Mindfulness and Mindful Eating

Mindfulness

Mindfulness—a keen awareness of an individual’s emotions and body without judgment—has various branches (e.g., meditation, mindful eating), imparts psychological and physiological benefits8–10 and is widely accessible. Research supports mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programs to be effective interventions for myriad chronic health conditions,11 including gastrointestinal disorders.12 For example, IBS sufferers respond favorably to MBSR programs utilizing practices such as diaphragmatic breathing, body scan, and meditation to target symptomology (e.g., pain from abdomen distension).13 Increased stress, which mindfulness programs address, is the unifying theme in such conditions. Since stress is part of most individuals’ lives, mindfulness is indicated as a preventative and therapeutic intervention.14

Mindful Eating

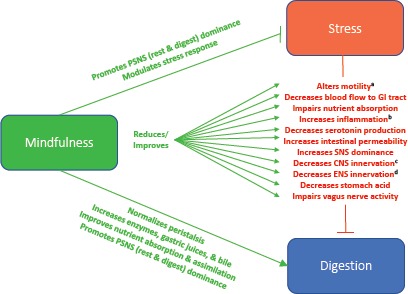

Mindful eating is the act of eating while being in a state of non-judgmental awareness, shifting one’s attention to the food and mind-body connection. Thus, allowing exploration of the complex cognitive-biological experience of eating. This healing eating mode favorably affects problematic eating habits (e.g., desensitizing hunger and satisfaction cues)13 and digestive disturbances attributed to stress.15 Refer to Figure 1, Table 1 and Appendix A for a detailed discussion of how these attenuations occur and strategies to implement mindful eating.

Figure 1.

Stress—Digestion—Mindfulness Triad

aMotility: decreased motility increases risk of dysbiosis; increased motility impairs nutrient absorption

bInflammation: increases pro-inflammatory cytokines, resistance to cortisol’s initial anti-inflammatory effect

cCNS innervation: dysregulated motility, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

dENS innervation: disrupted small segmentation contractions, peristalsis, and Migrating Motor Complex (MMC)

Table 1.

Clinical Application

|

| Intervention | Benefits | Sample Exercises |

|---|---|---|

|

Eating Slowly: Thoroughly chewing food aids breaking down food into absorbable components via mechanical and enzymatic actions. Simultaneously, increased time spent on chewing fosters awareness of chewing, while also promoting identification and response to internal signals. |

|

|

|

Meditation: Meditation and diaphragmatic breathing modulate the stress response. |

|

|

|

Hunger and Satiety: Food choices and eating driven by hunger and satiety signals influence digestion. |

|

|

|

Engaging Senses: Tasting food is one component of mindful eating. As sentient beings, all of the senses (e.g., smelling food, seeing food, touching food) are equally important.61,62 |

|

|

|

External Environment: The external environment characterizes emotions about eating and influences the nervous system.62 |

|

|

| Additional Resources | ||

| ||

Stress-Digestion-Mindfulness Triad

The stress-digestion-mindfulness triad is a hypothesized construct (See Figure 1), integrating what is understood about digestive function with literature about the nervous system, neuro-endocrine-immune signaling, stress, and mindfulness. Accepted physiology characterizes the interaction between the digestive and nervous systems—including the influence of gut hormones and the HPA-axis—and how stress impairs digestive function. This is bridged with evidence from human trials showing mindfulness practices as effective strategies for reducing symptom burden among those with FGIDs.12,16–19

The ANS and central nervous system (CNS) extrinsically innervate the digestive system for proper digestive function, while the same is accomplished by intrinsic innervation by the enteric nervous system (ENS).20,21 Approximately 90% of the serotonin in the body is concentrated in the ENS22 where it is synthesized and released by enterochromaffin (EC) cells.23 Serotonin is significant because it influences bowel motility, and senses and communicates information such as pain to the CNS.22,24,25 Research in women with IBS has found that tryptophan (serotonin precursor) depletion leads to altered central and peripheral serotonin, and the associated emotional arousal and pain sensitivity consistent with IBS.26

The Central Nervous System

The CNS promotes the muscular motility of the esophagus and stomach, and stomach acid secretion in response to the activated vago-vagal reflex.20,21 When CNS innervation is lost, dysregulated motility causes gastrointestinal symptoms such as stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.20 Hence, stress contributes to FGIDs such as IBS due to motility disturbances causing variations in gastric emptying and colonic contractions.27,28

The Autonomic Nervous System

The ANS also contributes to a dysregulated stress response and impaired digestive function. The ANS—responsible for maintaining homeostasis via chemical messengers—is subdivided into the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) or noradrenergic system, PSNS or cholinergic system, and ENS. While the SNS activates the fight-or-flight response during times of perceived or real threat, the PSNS elicits the rest-and-digest state. Therefore, PSNS activation is needed for optimal digestion.29,30

The PSNS can be activated through mindfulness practices (e.g., alternate nostril breathing).31 And established physiological knowledge shows that PSNS supports digestion by increasing salivary secretions, and stimulating gastric juices, digestive enzymes, and bile to facilitate nutrient assimilation and extraction.30 Thus, it is plausible that mind-body practices (e.g., mindful eating), which maintain PSNS dominance, help cultivate ANS homeostasis vital for optimal digestive function.

The Enteric Nervous System

Impaired ENS functioning may occur, which results in dysregulated bowel motility. Stress, along with infection gastrointestinal disturbances such as indigestion and IBS, may alter ENS function.32 The ENS, also known as the gut-brain axis or the body’s second brain (i.e., gut-brain), functions independent of the CNS but utilizes similar neurons and chemical messengers. Composed of over 100 million intrinsic neurons lining the walls of the gastrointestinal tract—from the esophagus to the internal anal sphincter21,33,34—the ENS is responsible for innervating the gastrointestinal tract.

The ENS is essential for controlling digestive functions such as small segmentation contractions that help mix contents with digestive enzymes and bring ingested food into contact with the intestinal wall for absorption. The retardation of contents moving through the intestine enhances digestion and absorption. Another ENS-controlled function includes peristalsis, rhythmic contractions or wave-like movements, helping to propel food through the esophagus and small intestine.35 Isolated contractions move contents orally and aborally (i.e., toward and away from the mouth), while segmentation contractions mix contents over a short distance in the intestine. Regarding peristalsis, contraction and relaxation occur, but contents move aborally.36

The Migrating Motor Complex (MMC) is also under ENS control.37–40 The vagus nerve controls the action of the MMC in the stomach, but not the intestine. And gut hormones initiate different MMC phases.41

Gut and Brain Bidirectionality

The CNS and ENS work synergistically to communicate information via neurotransmitters in a bidirectional manner between the gut and brain.21 When the brain perceives poor external factors (i.e., stress), it releases chemicals that stimulate the gut-brain to divert blood flow away from the gastrointestinal tract and toward organs that support survival (i.e., away from the trunk). When digestion is disturbed, the gut-brain communicates distress to the brain. Consequences include perturbations to mood and general health. Counteracting this, mindful eating may reduce stress to establish an environment that optimizes digestive capacity.12,13,15

HPA-Axis and the Chronic Stress Response-

Chronically elevated cortisol may lead to impaired digestive function—e.g., increased intestinal permeability, impaired absorption of micronutrients, abdominal pain or discomfort, and local and systemic inflammation as evidenced by soldiers combat-training.42 Chronic HPA-axis activation induces inflammation; resistance to the initial anti-inflammatory effect of cortisol develops, increasing pro-inflammatory cytokines43 and risk for inflammation-related issues (e.g., increased intestinal permeability) that may play a role in FGIDs.44–46

Clinical Application

The connection between neurogastrointestinal physiology and stress constructs a foundation for the clinical application of mindful eating to improve digestion. Research into the specialized branch of mindfulness—mindful eating—is in its infancy and has focused on weight loss through mindful-eating strategies. These include mindfulness meditation, breathing exercises, and facilitated discussions. Nevertheless, positive behavior change (i.e., increased awareness of internal signals, emotions, and external triggers) resulting in weight loss, and improved emotional stress and eating behavior are partly attributed to mindfulness-induced stress reduction.47,48 A systematic review and meta-analysis49 shows that mindfulness is integral to dealing with stress and mindfulness interventions are considered lifestyle medicine for diverse conditions, including those that impair digestion. Stress physiology is universal, but how individuals cope with stress influences health outcomes.

Mindful eating is an opportunity to non-judgmentally become aware of internal and external cues, sensations, and emotions.50 And it nurtures PSNS dominance—the condition of the nervous system associated with reduced stress. For additional details about interventions that foster mindful eating, refer to Table 1 and Appendix A.

When working with patients, clinicians must help them identify stress—individuals might not know how they experience stress—and should asses current eating practices. To identify stressors, clinicians may ask patients to select relevant symptoms from a list of stress-related symptoms, categorized into physical, emotional, mental, and social symptoms. During this process, clinicians can ask patients the last time they experienced each indicated symptom of stress and examine the events leading up to their presentations. Attention may be given to stressful events that correspond to digestive symptoms. This approach helps explore the antecedents and triggers of stress and compromised digestive capacity, which could be used to develop intervention strategies and overcome barriers to positive behavior changes. In addition, to assess current eating practices, clinicians can administer the Mindful Eating Questionnaire (MEQ), which covers five domains: (1) disinhibition, (2) awareness, (3) external cues, (4) emotional response, and (5) distraction.51

Patients may maintain a mindful-eating journal in which they record the time of the stress, symptom(s) of stress, eating activities surrounding the stress (i.e., before, during, and after symptom manifestation), and any internal self-talk that occurred. Recording this information helps affirm the reality of the issue, enhancing patients’ abilities to acknowledge problematic stress and take action. Based on research indicating that handwriting notes versus typing notes leads learners to better internalize information in a cognitively meaningful way,52 a hand-written journal (as opposed to typing or using a mobile application) reasonably facilitates improved cognitive processing.

Once patients identify stress and its cause(s), clinicians can help patients bring non-judgmental awareness to their physical and emotional responses to eating, while empowering them to identify and listen to their internal hunger and satiety cues.53 Motivational interviewing is a notable tool for exploring mindful-eating practices with which patients concur. Nonetheless, the utility of integrating mindful-eating interventions into clinical practice for improved eating behaviors, especially related to stress, is supported by the validity of the MEQ.51

Conclusion

Mindful eating is a non-standardized protocol that complements other interventions to optimize digestive function, while enhancing self-acceptance, mind-body-food awareness, and overall wellness. Consequently, a variety of practices from evidence-based mindfulness programs may be used to individualize care based on patients’ needs and readiness for change.

Central to mindful-eating practices for improved digestion is the attenuated stress response, encouraging nervous-system regulation to promote homeostasis needed for the rest-and-digest mode. Gastrointestinal and neuro-endocrine-immune signaling, and internal and external inputs comprise a complex psychosocial-physiological network that modulates optimal health. Within the context of that complex network, mindful eating offers a scientifically-proven, effective way to help regulate the stress response for optimal digestive function, which is the cornerstone of wellness and survival.

Acknowledgments

Christine E. Cherpak, BA, CIHC, is a doctoral candidate in Clinical Nutrition at Maryland University of Integrative Health (MUIH) in Laurel, Maryland, and founder of Kalena Spire, Inc. Sherryl Van Lare, MS, CNS, LDN, provided support with editing and data depiction. She is a doctoral student in Clinical Nutrition at MUIH and founder of Essential Wellness LLC. Christine E. Cherpak and Sherryl Van Lare are also on the faculty at MUIH.

APPENDIX A

Specific elaborations to support sample exercises in Table 1 (Clinical Application).

Hunger and Satiety

Sample exercise self-inquiry questions:

How do I feel before, during, and after eating (e.g., stressed, overwhelmed, bored, hungry, lightheaded, tired)?

Am I salivating before placing food into my mouth?

How does my tongue help me receive the food and am I aware of this muscular organ?

Are my feelings rooted in my physical or emotional bodies, or both?

External Environment

Sample exercise implementation strategy:

Partner with patients to identify one change they can make to create a more serene eating environment. Once successful, implement another change. Repeat this sequence until a relaxing eating environment is established.

References

- 1.Murray CDR, Flynn J, Ratcliffe L, Jacyna MR, Kamm MA, Emmanuel AV. Effect of acute physical and psychological stress on gut autonomic innervation in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(6):1695-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nam Y, Kwon S-C, Lee Y-J, Jang E-C, Ahn S. Relationship between job stress and functional dyspepsia in display manufacturing sector workers: a cross-sectional study. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2018;30:62 doi:10.1186/s40557-018-0274-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyrop KA, Palsson OS, Levy RL, et al. Costs of health care for irritable bowel syndrome, chronic constipation, functional diarrhoea and functional abdominal pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(2):237-248. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Josefsson A, Palsson O, Simrén M, Sperber AD, Törnblom H, Whitehead W. Oesophageal symptoms are common and associated with other functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) in an English-speaking Western population. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(10): 1461-1469. doi:10.1177/2050640618798894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guilliams T. The Role of Stress and the HPA Axis in Chronic Disease Management: Principles and Protocols for Healthcare Professionals. Stevens Point, WI: Point Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McEwen BS. Neurobiological and systemic effects of chronic stress. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). 2017;1 doi:10.1177/2470547017692328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konturek PC, Brzozowski T, Konturek SJ. Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62(6):591-599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grecucci A, Pappaianni E, Siugzdaite R, Theuninck A, Job R. Mindful emotion regulation: exploring the neurocognitive mechanisms behind mindfulness. Bio Med Res Int. 2015;2015 doi:10.1155/2015/670724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(6):537-559. doi:10.1177/1745691611419671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathieu J. What should you know about mindful and intuitive eating? J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(12):1982-1987. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann M, Kopf S, Kircher C, et al. Sustained effects of a mindfulness-based stress-reduction intervention in type 2 diabetic patients: design and first results of a randomized controlled trial (the Heidelberger Diabetes and Stress-study). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):945-947. doi:10.2337/dc11-1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zernicke KA, Campbell TS, Blustein PK, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome symptoms: a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20(3):385-396. doi:10.1007/s12529-012-9241-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaylord SA, Whitehead WE, Coble RS, et al. Mindfulness for irritable bowel syndrome: protocol development for a controlled clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:24 doi:10.1186/1472-6882-9-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gotink RA, Chu P, Busschbach JJV, Benson H, Fricchione GL, Hunink MGM. Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0124344 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Adeniyi PO. Stress, a major determinant of nutritional and health status. American Journal of Public Health Research. 2015;3(1):15-20. doi:10.12691/ajphr-3-1-3 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaylord SA, Palsson OS, Garland EL, et al. Mindfulness training reduces the severity of irritable bowel syndrome in women: results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(9):1678-1688. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IE Svebak S, Berstad A, Flatabø G, Hausken T. Breathing exercises with vagal biofeedback may benefit patients with functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(9):1054-1062. doi:10.1080/00365520701259208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berrill JW, Sadlier M, Hood K, Green JT. Mindfulness-based therapy for inflammatory bowel disease patients with functional abdominal symptoms or high perceived stress levels. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(9):945-955. doi:10.1016/j. crohns.2014.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zomorodi S, Abdi S, Tabatabaee SKR. Comparison of long-term effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus mindfulness-based therapy on reduction of symptoms among patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2014;7(2):118-124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Browning KN, Travagli RA. Central nervous system control of gastrointestinal motility and secretion and modulation of gastrointestinal functions. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(4):1339-1368. doi:10.1002/cphy.c130055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furness JB, Callaghan BP, Rivera LR, Cho H-J. The enteric nervous system and gastrointestinal innervation: integrated local and central control. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;817:39-71. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Ponti F. Pharmacology of serotonin: what a clinician should know. Gut. 2004;53(10):1520-1535. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.035568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mawe GM, Hoffman JM. Serotonin signalling in the gut--functions, dysfunctions and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(8):473-486. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2013.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fadgyas-Stanculete M, Buga A-M, Popa-Wagner A, Dumitrascu DL. The relationship between irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric disorders: from molecular changes to clinical manifestations. J Mol Psychiatry. 2014;2(1). doi:10.1186/2049-9256-2-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gershon MD, Tack J. The serotonin signaling system: from basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):397-414. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labus JS, Mayer EA, Jarcho J, et al. Acute tryptophan depletion alters the effective connectivity of emotional arousal circuitry during visceral stimuli in healthy women. Gut. 2011;60(9). doi:10.1136/gut.2010.213447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aucoin M, Lalonde-Parsi M-J, Cooley K. Mindfulness-based therapies in the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:140724 doi:10.1155/2014/140724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer EA. The neurobiology of stress and gastrointestinal disease. Gut. 2000;47(6):861-869. doi:10.1136/gut.47.6.861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Jonge WJ. The gut’s little brain in control of intestinal immunity. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2013;2013:630159 doi:10.1155/2013/630159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCorry LK. Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(4). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1959222/. Accessed October 6, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinha AN, Deepak D, Gusain VS. Assessment of the effects of pranayama/alternate nostril breathing on the parasympathetic nervous system in young adults. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(5):821-823. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2013/4750.2948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avetisyan M, Schill EM, Heuckeroth RO. Building a second brain in the bowel. J Clin Invest.. 2015;125(3):899-907. doi:10.1172/JCI76307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bornstein JC, Costa M, Grider JR. Enteric motor and interneuronal circuits controlling motility. Neurogastroenterol Motil.. 2004; 16 Suppl 1:34-38. doi:10.1111/j.1743-3150.2004.00472.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao M, Gershon MD. The bowel and beyond: the enteric nervous system in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(9):517-528. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2016.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huizinga JD, Chen J-H, Zhu YF, et al. The origin of segmentation motor activity in the intestine. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3326 doi:10.1038/ncomms4326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bharucha AE. High amplitude propagated contractions. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(11):977-982. doi:10.1111/nmo.12019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa M, Brookes S, Hennig G. Anatomy and physiology of the enteric nervous system. Gut. 2000;47(Suppl 4):iv15-iv19. doi:10.1136/gut.47.suppl_4.iv15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nezami BG, Srinivasan S. Enteric nervous system in the small intestine: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12(5):358-365. doi:10.1007/s11894-010-0129-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakajima H, Mochiki E, Zietlow A, Ludwig K, Takahashi T. Mechanism of interdigestive migrating motor complex in conscious dogs. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(5):506-514. doi:10.1007/s00535-009-0190-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaidel O, Lin HC. Uninvited guests: the impact of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth on nutritional status. Pract Gastroenterol. 2003;7:27-34. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deloose E, Janssen P, Depoortere I, Tack J. The migrating motor complex: control mechanisms and its role in health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9(5):271-285. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2012.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Kan EM, Lu J, et al. Combat-training increases intestinal permeability, immune activation and gastrointestinal symptoms in soldiers. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2013;37(8):799-809. doi:10.1111/apt.12269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian R, Hou G, Li D, Yuan T-F. A possible change process of inflammatory cytokines in the prolonged chronic stress and its ultimate implications for health. The Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014:780616 doi:10.1155/2014/780616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bertiaux-Vandaële N, Youmba SB, Belmonte L, et al. The expression and the cellular distribution of the tight junction proteins are altered in irritable bowel syndrome patients with differences according to the disease subtype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(12):2165-2173. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shulman RJ, Jarrett ME, Cain KC, Broussard EK, Heitkemper MM. Associations among gut permeability, inflammatory markers, and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(11):1467-1476. doi:10.1007/s00535-013-0919-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piche T, Barbara G, Aubert P, et al. Impaired intestinal barrier integrity in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: involvement of soluble mediators. Gut. 2009;58(2):196-201. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.140806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dalen J, Smith BW, Shelley BM, Sloan AL, Leahigh L, Begay D. Pilot study: Mindful Eating and Living (MEAL): weight, eating behavior, and psychological outcomes associated with a mindfulness-based intervention for people with obesity. Complement Ther Med. 2010;18(6):260-264. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Timmerman GM, Brown A. The effect of a mindful restaurant eating intervention on weight management in women. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(1):22-28. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2011.03.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Victorson D, Kentor M, Maletich C, Lawton R, Kaufman V. Mindfulness meditation to promote wellness and manage chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness-based randomized controlled trials relevant to lifestyle medicine. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2015;9(3):185-211. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kristeller JL, Wolever RQ. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: the conceptual foundation. Eat Disord. 2011;19(1):49-61. doi:10.1080/10640266.2011.533605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Framson C, Kristal AR, Schenk JM, Littman AJ, Zeliadt S, Benitez D. Development and validation of the mindful eating questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(8):1439-1444. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mueller P, Oppenheimer D. The pen is mightier than the keyboard: advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(6): 1159-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Meeting in the middle: motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:25 doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keller J, Layer P. The pathophysiology of malabsorption. Viszeralmedizin. 2014;30(3):150-154. doi:10.1159/000364794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goodman BE. Insights into digestion and absorption of major nutrients in humans. Adv Physiol Educ. 2010;34(2):44-53. doi:10.1152/advan.00094.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kulkarni BV, Mattes RD. Lingual lipase activity in the orosensory detection of fat by humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;306(12):R879-885. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00352.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tiwari M. Science behind human saliva. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2011;2(1):53-58. doi:10.4103/0976-9668.82322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schubert ML, Makhlouf GM. Gastrin secretion induced by distention is mediated by gastric cholinergic and vasoactive intestinal peptide neurons in rats. Gastroenterology. 1993;104(3):834-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma X, Yue Z-Q, Gong Z-Q, et al. The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Front Psychol. 2017;8:874 doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Melville GW, Chang D, Colagiuri B, Marshall PW, Cheema BS. Fifteen minutes of chair-based yoga postures or guided meditation performed in the office can elicit a relaxation response. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:501986 doi:10.1155/2012/501986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monroe JT. Mindful eating: principles and practice. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2015;9(3):217-220. doi:10.1177/1559827615569682 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daubenmier J, Kristeller J, Hecht F, et al. Mindfulness intervention for stress eating to reduce cortisol and abdominal fat among overweight and obese women: an exploratory randomized controlled study. J Obes. 2011;2011:651936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]