Abstract.

Significance: Collagen is a basic component of many tissues such as tendons, muscles, and skin, and its imaging helps diagnose and monitor treatments in a variety of fields, including orthopedics. However, due to the overlapping peaks of the absorption spectrum with water in the short-wave infrared region (SWIR), it is difficult to select an optimal wavelength and obtain the photoacoustic (PA) image for collagen-based tissues. Therefore, an additional approach to selecting the proper wavelength is needed.

Aim: The aim of this study is to derive an effective PA absorption spectrum of collagen to select the optimal wavelength for high-sensitive PA imaging (PAI).

Approach: We measure the absorption spectrum by acquiring the PA signal from various collagen-based samples. To derive an effective PA absorption spectrum in the SWIR band, the following two parameters should be considered: (1) the laser excitation for generating the PA signal and (2) the absorption spectrum for water in the SWIR band. This molecular intrinsic property suggests the optimal wavelength for high-sensitive PAI of collagen-based samples.

Results: PA absorption spectral peaks of collagen were found at wavelengths of 1200, 1550, and 1700 nm. Thereby, the PA signal increased by up to five times compared with the wavelength commonly used in collagen PAI. We applied a pulsed fiber laser with a center wavelength of 1560 nm, and the three-dimensional PA image of a collagen patch was obtained.

Conclusions: The effective PA absorption spectrum contributes to the improvement of the PA image sensitivity by presenting the optimal wavelength of the target samples.

Keywords: photoacoustic imaging, short-wave infrared, absorption spectrum, collagen, fiber laser

1. Introduction

Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is a promising hybrid imaging technique for biomedical applications, combining optical contrast and acoustic resolution.1 PAI provides anatomical and functional information based on strong optical absorption sensitivity.1–3 The optimization of the wavelength according to the target molecule can enhance the selectivity of the visualization of target organs and allows for the extension into functional PAI such as multispectral imaging.4,5 Typically, in the ultraviolet region (10 to 400 nm), the imaging of cell nuclei is performed utilizing the strong absorption by DNA and RNA at wavelengths of .6 In the visible (VIS) region (400 to 700 nm), vascular imaging is typically performed using wavelengths of around 532 nm.7 In the first window of the near-infrared region (NIR-I, 700 to 1000 nm), previous research has achieved relatively deep vascular imaging by taking advantage of the low light attenuation.8 Additionally, to delineate transparent organs such as lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tracts, and bladders, labeled imaging has also been performed using several contrast agents, such as indocyanine green or methylene blue.9–12 The second window of the NIR (NIR-II) region, also called short-wave infrared region (SWIR, defined here as 1100 to 2000 nm), is of current interest due to the relative low levels of scattering and the high-maximum permissible exposure compared with the NIR-I region.12–15 Additionally, in the SWIR band, we find the optical absorption peaks of water, collagen, and lipids, three major molecules of human tissues.15–17

Collagen is an important substance that is the basis of tissues such as the tendons, ligaments, and muscles in our body, and its imaging helps with the diagnosis and monitoring of treatments in a variety of fields, including orthopedics, dermatology, and cardiology. Recently, the imaging of collagen and collagen-based tissues using the PAI method was reported.18,19 Even though the optical absorption by collagen is relatively high in the VIS and NIR-I wavelength ranges, it still requires precise optical alignment and a complex acoustic capturing process to measure the PA signals of collagen in biological tissue due to the dominant concentration of oxy-/deoxy-hemoglobin (Hb) in whole blood and its morphological proximity to the blood vessels. Therefore, one solution involves looking for an effective collagen absorption spectrum in the SWIR band, which presents two main benefits: (1) avoiding the interference from whole blood and (2) achieving almost an order of magnitude higher absorption by collagen than with the NIR-I band.15–17 The absorption peaks of collagen in the SWIR band were reported at wavelengths of 1200, 1500, and 1725 nm.17,20,21 Unfortunately, these peaks overlap with the absorption peaks of water, which are found at wavelengths of 1180, 1430, and 1930 nm.17,22 This is a critical issue in delivering light into collagen samples. Normal PAI systems utilize water or water gel as the medium for acoustic propagation, so high-absorption losses during laser delivery may lead to insufficient PA signals. To derive an effective PA absorption spectrum for collagen in the SWIR band, the following two parameters should be considered: (1) the laser excitation for generating the PA signal and (2) the absorption spectrum for water in the SWIR band.

In this paper, we measure the absorption spectrum by acquiring the PA signal from various collagen-based samples to find the optimal wavelength for the particular PA application. The effective PA spectrum of collagen can be calculated by measuring the absorption spectrum of PA signals and the absorption spectrum of water in the SWIR band. The calculated collagen PA spectrum was compared with the optical absorption spectra presented in previous research. To demonstrate the utility of the effective PA spectrum, a three-dimensional (3-D) PA image of a collagen sample was obtained using the selected wavelength.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Effective Photoacoustic Absorption Spectrum

According to the PA effect equation, the local pressure rise can be expressed as follows:23

| (1) |

When laser pulses with optical fluence irradiate the target, the chromophore in the sample absorbs photon energy with absorbance . This is then converted into heat with efficiency , and the thermal expansion causes a change in the energy of the phonon, which is a vibrational property that depends on the Grüneisen parameter . Since is a function of temperature and is a constant of energy conversion efficiency, these are independent variables for wavelength. The effective PA absorption spectrum , as a function of the wavelength only, can be obtained by dividing the PA signal amplitude by the laser fluence :24

| (2) |

By normalizing this spectrum, a value proportional to can be obtained. This represents the PA effects from the light absorption to the vibration conversion and leads to the information on the components.

To calculate the actual laser fluence reaching the sample, compensation for the optical attenuation from the medium needs to be factored in with the Beer–Lambert law as follows:

| (3) |

where is the laser output fluence after the water tank without the medium and is the optical attenuation coefficient of the medium with the path length (in centimeters). In the case in which water is the medium, the optical attenuation coefficient can be replaced by the optical absorption coefficient. The light scattering coefficient can be ignored because it is eight orders of magnitude lower than the absorption coefficient in the SWIR band.25 The entire process for obtaining the effective PA absorption spectrum is summarized as a flowchart in Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material.

2.2. Experimental Setup

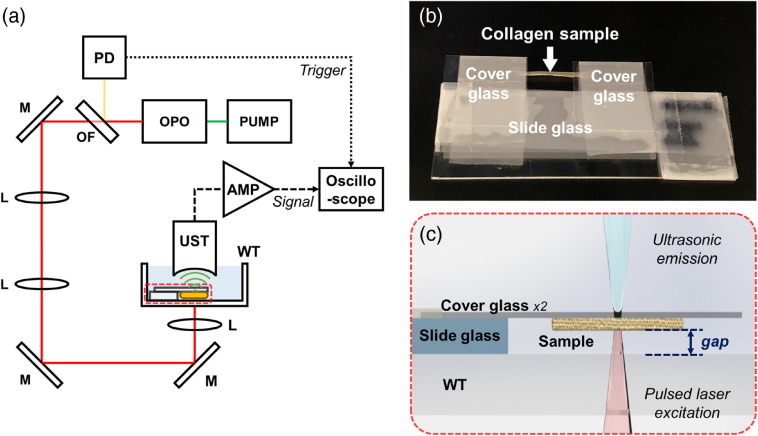

Figure 1 shows the schematic of the experimental setup used to measure the effective PA absorption spectrum. The optical parametric oscillator (OPO) (Surelite OPO Plus, Continuum) pulsed laser with a 532-nm wavelength pump (SL EX, Continuum) was used. The laser has a pulse width of 3 to 5 ns, a repetition rate of 10 Hz, and an idler tuning range from 1150 to 1950 nm. The colored glass filter (FGL610, Thorlabs) was used as an optical long-pass filter for the idler output only. An ultrasonic transducer (V324-SM, Olympus NDT) with a center frequency of 25 MHz and a focal length of 0.75 inches, a digital oscilloscope (DS4054, RIGOL), and two amplifiers (ZX60-3018G-S+, 45.2 dB gain, Mini-Circuits) were used for PA signal acquisition.

Fig. 1.

(a) Schematic diagram for the measurement system for the effective PA absorption spectrum. (b) Photograph of the sample preparation. (c) Side view of an enlarged diagram of the sample positioning. OPO, optical parametric oscillator; OF, optical filter; PD, photodetector; M, mirror; L: lens; WT, water tank; UST, ultrasonic transducer; and AMP, amplifier.

We used three different samples. The first sample was a collagen patch (CGDerm, CGBio), which is widely used clinically for a bridging graft or reconstruction surgery of collagen-based tissues. The second and third samples were fiber bundles extracted from the tail and Achilles tendons of the mouse (BALB/c Nude, male, 9 to 10 weeks old), respectively. All animal-handling protocols were followed as per the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Republic of Korea. Before the experiment, all samples were immersed in deionized water for 1 h to minimize the effect of hydration during the experiment. The samples were hung under two cover glasses as shown in Fig. 1(b). A section on top of the sample was left uncovered by the cover glasses to prevent acoustic signal loss.

The gap between the sample and the water tank, as shown in Fig. 1(c), was controlled to be under 1 mm by stacking on the slide glass. The exact value of the gap for each sample was calculated by the delay time of the acoustic wave for the laser trigger and the sound velocity of the medium. The acoustic delay was recorded by the time difference between two PA signals from the membrane of the water tank and the target sample. The speed of sound in water was assumed to be , which when multiplied by the time interval gives the path length used in Eq. (3).

3. Results

3.1. Measurement of the Effective PA Absorption Spectrum of Collagen

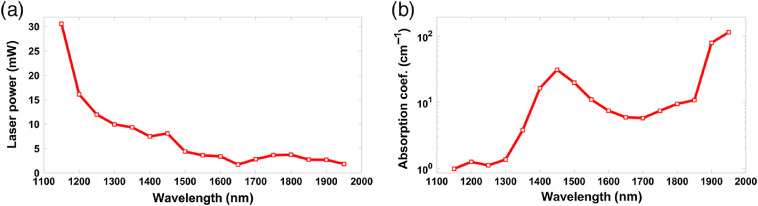

Before the PA measurement, the optical attenuation of deionized water was measured with an optical power meter (S310, Thorlabs). Using a collimated beam penetrating a cuvette (100-2-20, Hellma Analytics), the laser power with and without water was compared and the optical absorption spectrum of the medium was obtained to calculate each path length. The measurement step size of the laser output wavelength was maintained at 50 nm within the entire tuning range. Figure 2(a) shows the output power of the OPO laser, labeled , after the unfilled water tank. Figure 2(b) shows the optical absorption coefficient of water, labeled .

Fig. 2.

(a) Laser power spectrum and (b) optical absorption spectrum of water.

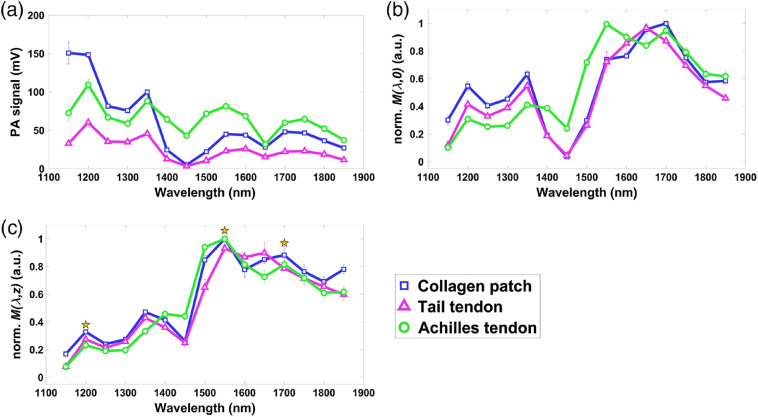

The PA signal amplitude spectra of each type of collagen-based tissue are shown in Fig. 3(a). All samples were prepared separately; in total there were two collagen patches, three tail tendon fiber bundles, and four Achilles tendon fiber bundles. By simply dividing the signal amplitude by the laser fluence (after the unfilled water tank), , we arrive at the spectrum shown in Fig. 3(b). The effective PA absorption spectrum of the samples, with compensation for the optical attenuation over the path length , is shown in Fig. 3(c). Both Figs. 3(b) and 3(c) have been normalized based on the maximum PA values of each sample. Peaks in the effective PA absorption spectrum appear at wavelengths of , 1550, and 1700 nm, showing the same spectrum for all three collagen-based tissues.

Fig. 3.

(a) PA signal spectra of collagen-based samples. (b) Normalized effective PA absorption spectra of samples without compensation for optical attenuation. (c) Normalized effective PA absorption spectrum for PAI of collagen with compensation for optical attenuation of water.

The averaged peak values were 0.28, 0.98, and 0.85, respectively. In previous research,15 normalized absorption values were also measured as 0.29 and 0.96 at wavelengths of 1200 and 1550 nm, respectively. Other measurements of the absorption spectrum of collagen were reported at , 1.3, and 1.5 at wavelengths of 1200, 1500, and 1700 nm, respectively.16 The variance in absorption values could be caused by the degree of molecular density.

The strong light attenuation from water at makes the PA signal too small to accurately calculate the absorption value. The dry collagen has the optical absorption peak of 1500 nm.17,21 However, the effective PA absorption shifts the peak from 1500 nm to 1550 nm, considering the light absorption of water.

The effective PA absorption spectrum indicates the efficiency with which target molecules can generate PA signals per laser fluence. By compensating for the light attenuation in the medium, this molecular intrinsic property suggests the optimal wavelength for high-sensitive PAI of collagen-based samples (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material).

3.2. PA Imaging of Collagen-Based Tissue

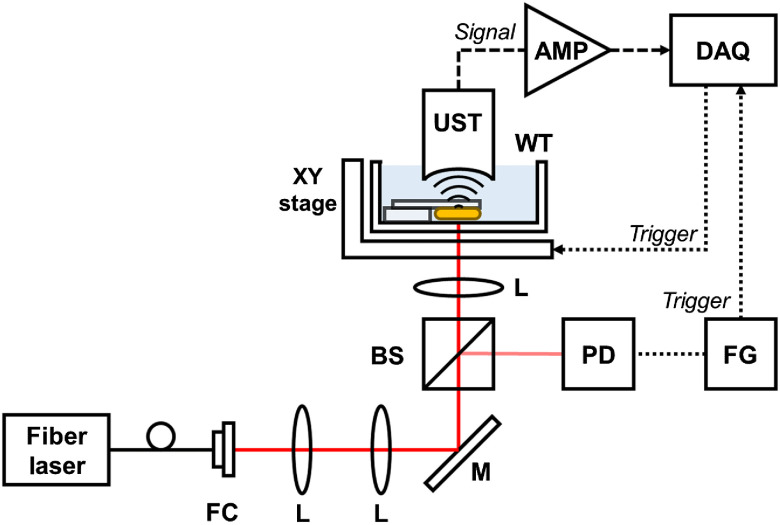

We constructed the PA microscopy (PAM) system for collagen patch sample imaging. Figure 4 shows the schematic diagram of the experimental setup for the PAM system. To exploit the high optical absorption of the collagen sample, a pulsed fiber laser (made in the lab, APRI) was used with a center wavelength of 1560 nm, a pulse width of , and a repetition rate of 5 kHz. A polarizing beam splitter (GL10-C, Thorlabs) was used to split the beam to enter the photodetector (PDA10CF-EC, Thorlabs). The burst signal from a function generator synchronized the laser pulse output, signals for a digitizer (PX14400, Signatec) and an XY-stage (PLS-XY, Thorlabs). The UST and amplifiers for the PA signal measurements are the same as those used previously. The data acquisition software was developed in LabVIEW (National Instruments) with a per volume dataset, and the sampling rate for PA signal acquisition was .

Fig. 4.

Schematic diagram of the PAI system. FC, fiber coupler; BS, beam splitter; FG, function generator; and DAQ, data acquisition board.

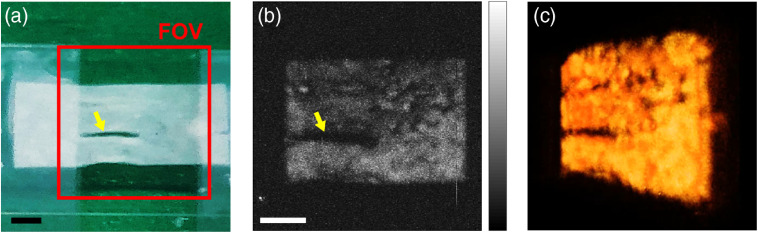

Figure 5(a) shows a photograph of the collagen patch sample prepared for PAI. The collagen patch was the same sample as measured in the PA spectrum. The red square box indicates the field of view (FOV) of . The corresponding PA maximum amplitude projection (MAP) image is shown in Fig. 5(b). The PA image of the collagen sample shows the detailed structure of the target patch, including a damaged region marked by the inset yellow arrow. Owing to the sufficient optical absorption at a wavelength of 1560 nm, we obtained a 3-D PA image of the collagen patch as shown in Fig. 5(c). In the MAP image [Fig. 5(b)], the measured signal-to-noise ratio of the collagen patch is (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Material).

Fig. 5.

(a) Photograph of a collagen patch sample for PAI. (b) Corresponding PA MAP image. (c) 3-D PA image of the collagen patch (Video 1). FOV, field of view. The inserted scale bar is 1 mm. (Video 1, 5.74 MB, MP4 [URL: https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.25.5.056002.1].)

4. Discussion and Conclusion

By employing the PA methods, we were able to measure the optical absorption by collagen in the SWIR region and derive its effective PA absorption spectra. The spectra were obtained not only by normalization to the laser fluence but also by compensating for the light loss due to the water medium. The PA absorption peaks of collagen were found at wavelengths of 1200, 1550, and 1700 nm, which are almost identical to the values previously reported in literature.15 A wavelength of 1550 nm was chosen as optimal for collagen imaging. We applied a pulsed fiber laser with an output wavelength of 1560 nm and obtained the 3-D PA image of the collagen patch.

Comparing the B-scan images (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Material) of the collagen patch at wavelengths of 1200, 1310, and 1560 nm with the same laser fluence, the normalized PA signals of the inset box were measured as 0.17, 0.23, and 0.92, respectively. At 1560 nm, that was up to five times over what is possible with wavelengths of 1200 and 1310 nm, which are commonly used in collagen PAI.18,19 This confirms the utility of the effective PA absorption spectrum and optimal wavelength for PAI of collagen-based tissues, thereby contributing to an improvement in the PA image sensitivity.

The accuracy of the spectrum and the sensitivity of the image can be further improved by precisely modeling the PAM system to address issues such as acoustic attenuation and impedance mismatch. This method also allows for the measurement of the effective PA absorption spectrum of many other molecules, such as lipids. Additionally, this method can be extended for high-selective functional PAI in a variety of fields, including orthopedics and cardiology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Yang-Gyeong Kim and Prof. Myung-Sun Kim for helping us to prepare the biological samples. This research was supported by the Industrial Technology Innovation Program (No. 10063364) of the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy of Korea and a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (No. HI18C0858).

Biographies

Eunwoo Park received his BS and MS degrees in mechanical engineering from Dankook University, Republic of Korea, in 2016 and 2017, respectively. He has been working at the Advanced Photonics Research Institute, Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Republic of Korea, since 2018. His current research interests include optical imaging systems.

Yong-Jae Lee received his BS degree and PhD in physics from Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, in 2012 and 2018, respectively. He was a research scientist at the Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute, Daejeon, Republic of Korea. He has been working at the Advanced Photonics Research Institute, Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Gwangju, Republic of Korea, since 2018. His current research interests include optical coherence tomography and photoacoustic imaging.

Changho Lee received his PhD in 2013 from Kyungpook National University. He has been an assistant professor at Chonnam National University (CNU), Republic of Korea, since 2017. Before joining CNU, he worked as an assistant research professor and a postdoctoral fellow at POSTECH (2013 to 2016) and Johns Hopkins University (2016 to 2017). He focused on developing innovative-biomedical imaging modalities such as optical coherence tomography, photoacoustic imaging, multimodal optical imaging, molecular optical imaging, and intraoperative surgical imaging.

Tae Joong Eom received his diploma degree from Pusan National University, Busan, Republic of Korea, and his MS degree and PhD from Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST), Gwangju, Republic of Korea, in 2000 and 2005, respectively. He was a research scientist at Beckman Laser Institute, University California, Irvine, California, USA, and at Washington University in St. Louis. Since 2005, he has been working as a principal research scientist at the Advanced Photonics Research Institute of GIST. His research interests include functional optical imaging.

Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Eunwoo Park, Email: statice13@gist.ac.kr.

Yong-Jae Lee, Email: maximcoffee@gist.ac.kr.

Changho Lee, Email: ch31037@jnu.ac.kr.

Tae Joong Eom, Email: eomtj@gist.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Wang L. V., et al. , “Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs,” Science 335(6075), 1458–1462 (2012). 10.1126/science.1216210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X., et al. , “Noninvasive laser-induced photoacoustic tomography for structural and functional in vivo imaging of the brain,” Nat. Biotechnol. 21(7), 803–806 (2003). 10.1038/nbt839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao J., et al. , “High-speed label-free functional photoacoustic microscopy of mouse brain in action,” Nat. Methods 12(5), 407–410 (2015). 10.1038/nmeth.3336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang J. M., et al. , “Simultaneous functional photoacoustic and ultrasonic endoscopy of internal organs in vivo,” Nat. Med. 18(8), 1297–1302 (2012). 10.1038/nm.2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taruttis A., et al. , “Advanced in real-time multispectral optoacoustic imaging and its applications,” Nat. Photonics 9(4), 219–227 (2015). 10.1038/nphoton.2015.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao D. K., et al. , “Optimal ultraviolet wavelength for in vivo photoacoustic imaging of cell nuclei,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(5), 056004 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.5.056004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao J., et al. , “Label-free oxygen-metabolic photoacoustic microscopy in vivo,” J. Biomed. Opt. 16(7), 076003 (2011). 10.1117/1.3594786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hai P., et al. , “Near-infrared optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy,” Opt. Lett. 39(17), 5192–5195 (2014). 10.1364/OL.39.005192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y. J., et al. , “Photoacoustic imaging probe for detecting lymph nodes and spreading of cancer at various depths,” J. Biomed. Opt. 22(9), 091513 (2017). 10.1117/1.JBO.22.9.091513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erpelding T. N., et al. , “Sentinel lymph nodes in the rat: noninvasive photoacoustic and US imaging with a clinical US system,” Radiology 256(1), 102–110 (2010). 10.1148/radiol.10091772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo S. W., et al. , “Biodegradable contrast agents for photoacoustic imaging,” Appl. Sci.-Basel 8(9), 1567 (2018). 10.3390/app8091567 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung D., et al. , “Recent progress on near-infrared photoacoustic imaging: imaging modality and organic semiconducting agents,” Polymers 11(10), 1693 (2019). 10.3390/polym11101693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong G., et al. , “Near-infrared fluorophores for biomedical imaging,” J. Biomed. Opt. 1(1), 0010 (2017). 10.1038/s41551-016-0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upputuri P. K., et al. , “Photoacoustic imaging in the second near-infrared window: a review,” J. Biomed. Opt. 24(4), 040901 (2019). 10.1117/1.JBO.24.4.040901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nachabe R., et al. , “Diagnosis of breast cancer using diffuse optical spectroscopy from 500 to 1600 nm: comparison of classification methods,” J. Biomed. Opt. 16(8), 087010 (2011). 10.1117/1.3611010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekar S. K. V., et al. , “Diffuse optical characterization of collagen absorption from 500 to 1700 nm,” J. Biomed. Opt. 22(1), 015006 (2017). 10.1117/1.JBO.22.1.015006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson R. H., et al. , “Review of short-wave infrared spectroscopy and imaging methods for biological tissue characterization,” J. Biomed. Opt. 20(3), 030901 (2015). 10.1117/1.JBO.20.3.030901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan Y., et al. , “Photoacoustic imaging of the uterine cervix to assess collagen and water content changes in murine pregnancy,” Biomed. Opt. Express 10(9), 4643–4655 (2019). 10.1364/BOE.10.004643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Y., et al. , “Identifying intestinal fibrosis and inflammation by spectroscopic photoacoustic imaging: an animal study in vivo,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9(4), 1590–1600 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.001590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang P., et al. , “Mapping lipid and collagen by multispectral photoacoustic imaging of chemical bond vibration,” J. Biomed. Opt. 21(9), 096010 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.21.9.096010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang P., et al. , “Bond-selective imaging of deep tissue through the optical window between 1600 and 1850 nm,” J. Biophotonics 5(1), 25–32 (2011). 10.1002/jbio.201100102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen T. J., et al. , “Spectroscopic photoacoustic imaging of lipid-rich plaques in the human aorta in the 740 to 1400 nm wavelength range,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(6), 061209 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.6.061209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L. V., Wu H., Biomedical Optics: Principles and Imaging, Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey: (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao D. K., et al. , “Photoacoustic measurement of the Grüneisen parameter of tissue,” J. Biomed. Opt. 19(1), 017007 (2014). 10.1117/1.JBO.19.1.017007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buiteveld H., et al. , “Optical properties of pure water,” Proc. SPIE 2258, 174–183 (1994). 10.1117/12.190060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.