Abstract

Despite the importance of dendritic targeting in neural circuit assembly, the mechanisms by which it is controlled still remain incompletely understood. We previously showed that in the developing Drosophila antennal lobe, the Wnt5 protein forms a gradient that directs the ~45˚ rotation of a cluster of projection neuron (PN) dendrites, including the adjacent DA1 and VA1d dendrites. We report here that the Van Gogh (Vang) transmembrane planar cell polarity (PCP) protein is required for the rotation of the DA1/VA1d dendritic pair. Cell type-specific rescue and mosaic analyses showed that Vang functions in the olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs), suggesting a codependence of ORN axonal and PN dendritic targeting. Loss of Vang suppressed the repulsion of the VA1d dendrites by Wnt5, indicating that Wnt5 signals through Vang to direct the rotation of the DA1 and VA1d glomeruli. We observed that the Derailed (Drl)/Ryk atypical receptor tyrosine kinase is also required for the rotation of the DA1/VA1d dendritic pair. Antibody staining showed that Drl/Ryk is much more highly expressed by the DA1 dendrites than the adjacent VA1d dendrites. Mosaic and epistatic analyses showed that Drl/Ryk specifically functions in the DA1 dendrites in which it antagonizes the Wnt5-Vang repulsion and mediates the migration of the DA1 glomerulus towards Wnt5. Thus, the nascent DA1 and VA1d glomeruli appear to exhibit Drl/Ryk-dependent biphasic responses to Wnt5. Our work shows that the final patterning of the fly olfactory map is the result of an interplay between ORN axons and PN dendrites, wherein converging pre- and postsynaptic processes contribute key Wnt5 signaling components, allowing Wnt5 to orient the rotation of nascent synapses through a PCP mechanism.

Author summary

During brain development, the processes of nerve cells, axons and dendrites, grow over long distances to find and connect with each other to form synapses in precise locations. Understanding the mechanisms that control the growth of these neurites is important for understanding normal brain functions like neuronal plasticity and neural diseases like autism. Although much progress has been made by studying the development of axons and dendrites separately, the mechanisms that guide neuronal processes to their final locations are still incompletely understood. In particular, careful observation of converging pre- and postsynaptic processes suggests that their targeting may be coordinated. Whether the final targeting of axons and dendrites are functionally linked and what molecular mechanisms may be involved are unknown. In this paper we show that, in the developing Drosophila olfactory circuit, coalescing axons and dendrites respond to the extracellular Wnt5 signal in a codependent manner. We demonstrate that the converging axons and dendrites contribute different signaling components to the Wnt5 pathway, the Vang Gogh and Derailed transmembrane receptors respectively, which allow Wnt5 to coordinately guide the targeting of the neurites. Our work thus reveals a novel mechanism of neural circuit patterning and the molecular mechanism that controls it.

Introduction

The prevailing view of neural circuit assembly is that axons and dendrites are separately guided by molecular gradients to their respective positions whereupon they form synapses with each other [1–4]. However, careful observation of developing neural circuits reveals that the process may be more complex. For example, in the developing retina outer plexiform layer (OPL) the axon terminals of rods and cones, and dendrites of their respective postsynaptic cells, the rod and cone bipolar cells, are initially intermingled in the nascent OPL [5]. Even as the rod and cone axons are connecting with their target dendrites, the terminals are segregating into rod- and cone-specific sub-laminae, suggesting that the processes of targeting and synaptic partner matching may be coordinated. Whether the two processes are functionally linked and what mechanisms might be involved are unknown.

The stereotyped neural circuit of the Drosophila olfactory map offers a unique opportunity to unravel the mechanisms of neural circuit development. Dendrites of 50 classes of uniglomerular projection neurons (PNs) form synapses with the axons of 50 classes of olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) in the antennal lobe (AL) in unique glomeruli [6, 7]. This precise glomerular map is thought to be established during the pupal stage by the targeting of PN dendrites [8–10]. We previously reported that during the establishment of the fly olfactory map, two adjacent dendritic arbors located at the dorsolateral region of the AL, the DA1 and VA1d dendrites (hereafter referred to as the DA1/VA1d dendritic pair), undergo rotational migration of ~45˚ around each other to attain their final adult positions [11]. This rearrangement (in the lateral/90˚ → dorsal/0˚ → medial/270˚ → ventral/180˚ direction) occurs between 16 and 30 hour After Puparium Formation (hAPF), a period of major ORN axon ingrowth to the AL [8, 12, 13]. We showed that a Wnt5 signal guides this rotation by repelling the dendrites [11]. Wnt5 is expressed by a set of AL-extrinsic cells and forms a dorsolateral-high to ventromedial-low (DL>VM) gradient in the AL neuropil which provides a directional cue to align the dendritic pattern relative to the axes of the brain. We also showed that the Derailed (Drl)/Ryk kinase-dead receptor tyrosine kinase, a Wnt5 receptor [14–17], is differentially expressed by the PN dendrites, thus providing cell-intrinsic information for their targeting in the Wnt5 gradient. Interestingly, drl opposes Wnt5 repulsive signaling so that dendrites expressing high levels of drl terminate in regions of high Wnt5 concentration and vice versa. To further unravel the mechanisms of PN dendritic targeting, we have screened for more mutations that disrupt the rotation of the DA1/VA1d dendritic pair.

Here we report that mutations in the Van Gogh (Vang) gene disrupted the rotation of the DA1/VA1d dendritic pair, thus mimicking the Wnt5 mutant phenotype. Vang encodes a four-pass transmembrane protein [18, 19] of the core Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) group, an evolutionarily conserved signaling module that imparts polarity to cells [20, 21]. The loss of Vang suppressed the repulsion of the VA1d dendrites by Wnt5, indicating that Vang is a downstream component of Wnt5 signaling. Surprisingly, Vang acts in the ORNs, which suggests an obligatory codependence of ORN axon and PN dendritic migration. We also show that the drl gene is selectively expressed in the DA1 dendrites where it antagonizes Vang and appears to convert Wnt5 repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus into attraction. The opposing responses of the DA1 and VA1d glomeruli likely create the forces by which Wnt5 directs the rotation of the glomerular pair. Our work shows that converging pre- and postsynaptic processes contribute key signaling components of the Wnt5 pathway, allowing the processes to be co-guided by the Wnt5 signal.

Results

Vang promotes the rotation of DA1/VA1d dendrites

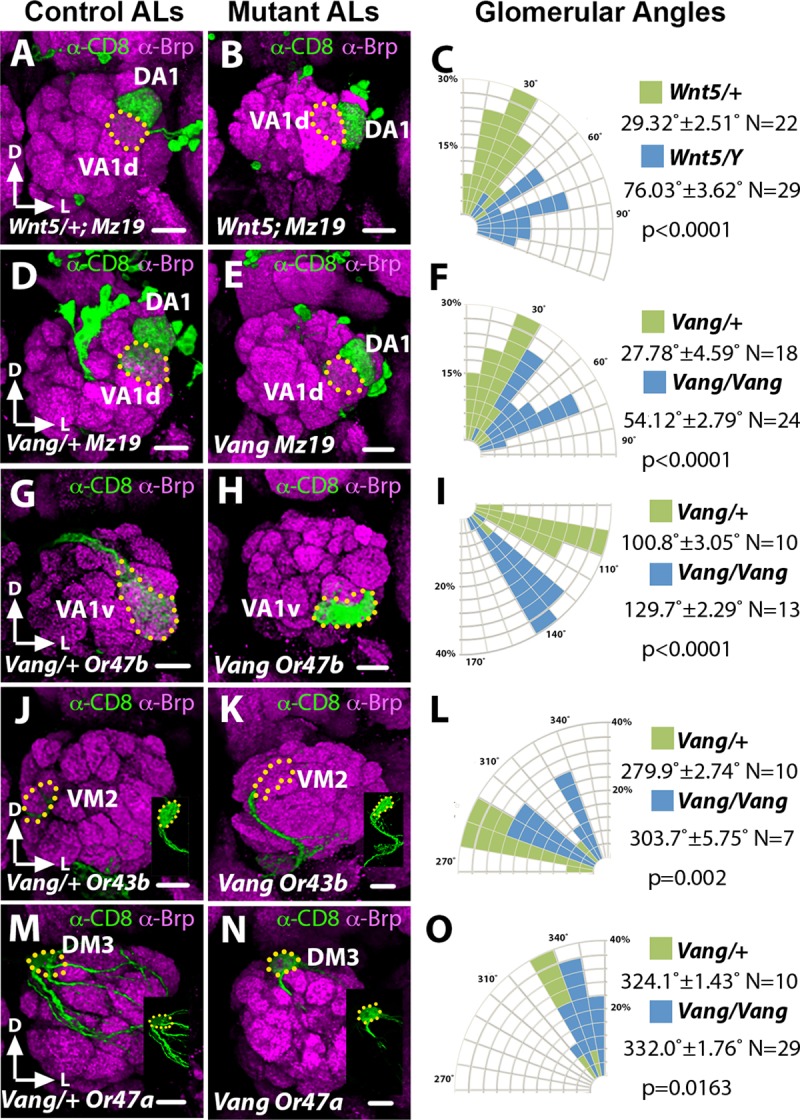

We have shown that during wild-type development the adjacent DA1 and VA1d dendrites rotate around each other, such that DA1 moves from its original position lateral to VA1d at 18 hAPF to its final position dorsolateral to VA1d in the adult, an ~45˚ rotation [11]. We also showed that this rotation requires the Wnt5 gene, for in the null Wnt5400 mutant the rotation is abolished, resulting in an adult DA1/VA1d angle of 76.03˚ ± 3.6˚ (N = 29, vs 29.32˚ ± 2.5˚, N = 22 in the Wnt5400/+ heterozygous control, Student’s t test p<0.0001) (See Materials and Methods and S1 Fig for quantification) (Fig 1A–1C). The DA1 and VA1d pair of dendrites were visualized by expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4, which specifically labels the DA1, VA1d and DC3 dendrites [22, 23]. To elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which Wnt5 controls the rotation of the PN dendrites, we screened a panel of signal transduction mutants for similar defects in DA1/VA1d rotation. We found that animal homozygous for Vang mutations exhibit a DA1/VA1d phenotype that mimicked that of the Wnt5400 mutant. For example, in the null Vang6 allele, the DA1/VA1d angle was 54.72˚ ± 2.8˚ (N = 24, vs 27.78˚ ± 4.6˚, N = 18 in the Vang6/+ heterozygous control, t-test p<0.0001) (Fig 1D–1F) suggesting that Vang might function in the Wnt5 pathway. Since the Vang6 allele, which encodes a truncated 128 amino acid product [19], displayed a highly penetrant phenotype, we examined this allele further. We therefore examined the positioning of glomeruli in different regions of the Vang6 AL by expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of various Or-Gal4 drivers [6] (Fig 1G–1O, see Materials and Methods for quantification). We observed that glomeruli in the lateral region of the AL, such as the VA1v glomerulus (Fig 1G–1I), showed the greatest displacement compared with glomeruli in other regions, suggesting that Vang primarily controls neurite targeting in the lateral AL. Since the Wnt5 protein is highly concentrated at the dorsolateral region of the AL [11], the Vang mutant defects are consistent with Vang playing a role in Wnt5 signaling. We hypothesized that Vang mediates Wnt5 signaling in the control of the DA1/VA1d dendritic rotation.

Fig 1. The Vang6 mutant AL defects mimic that of the Wnt5400 mutant.

Frontal views of the left ALs are shown (dorsal up and lateral to the right) in this and following figures. (A-F) Adult ALs from animals expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 stained with antibodies against Bruchpilot (Brp, Magenta) to highlight the AL neuropil and CD8 (green) to highlight the DA1 and VA1d PN dendritic arbors in the Wnt5400/+ (A) and Vang6/+ (D) controls, and Wnt5400 (B) and Vang6 (E) mutants. (C, F) Quantification of the DA1/VA1d angles in the Wnt5400 and Vang6 mutants respectively. The DA1 dendrites are located dorsal to the VA1d dendrites in the controls but lateral to the VA1d dendrites in the Wnt5400 and Vang6 mutants. (G-O) Left adult ALs from animals expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Or47b-Gal4 (G, H), Or43b-Gal4 (J, K) and Or47a-Gal4 (M, N) to label lateral, medial and dorsal glomeruli respectively, in the Vang6/+ (G, J, M) controls and Vang6 mutants (H, K, N). (I, L, O) Quantification of the positions of the Or47b, Or43b and Or47a glomeruli respectively in the control vs Vang6 animals. The glomeruli appeared to be displaced in the clockwise direction in the Vang6 mutant, with VA1v showing the greatest displacement. Insets (J, K, M, N) show the ORN terminals in the absence of Brp staining. Student’s t tests were used to compare the data of the mutants with those of their respective controls. Scale bars: 10 μm.

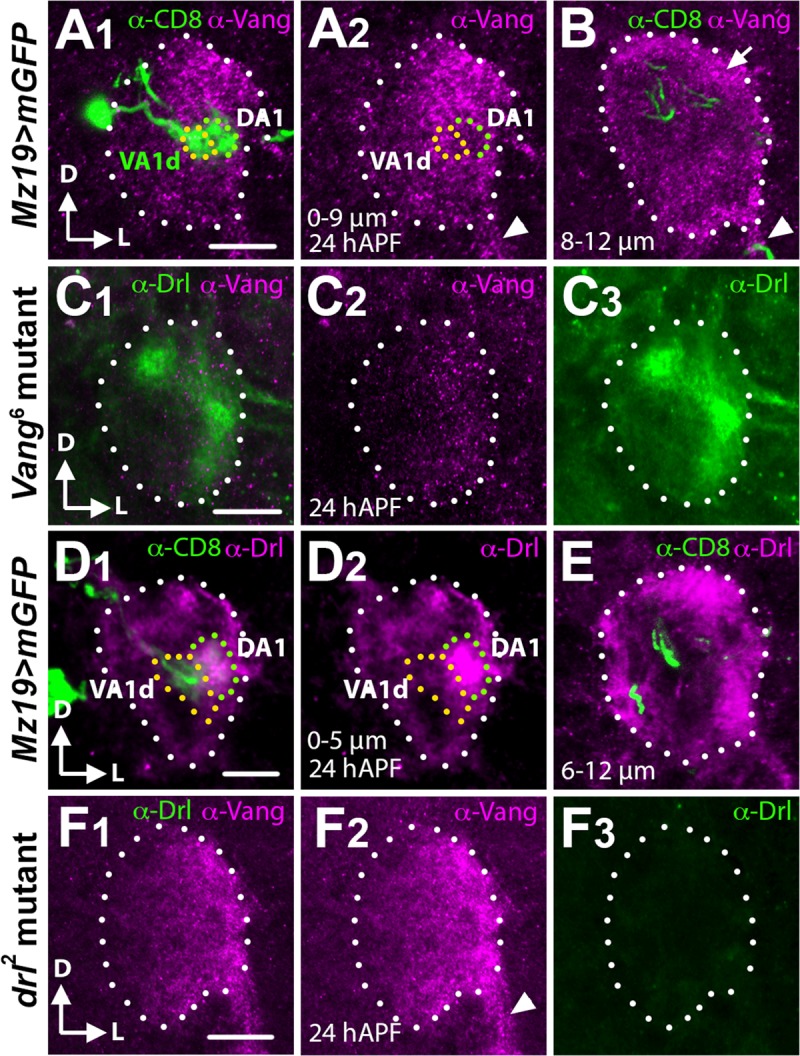

To obtain further evidence for Vang’s role in regulating the rotation of the DA1/VA1d dendritic pair, we stained ALs during a time of active glomerular rotation (24 hAPF) [11] with an antibody directed against the N-terminal 143 amino acids of Vang [24]. We observed that the Vang staining has a punctate appearance and is highly concentrated in the dorsolateral region of the AL between 0–9 μm from the AL anterior surface (Fig 2A). Co-labeling of the DA1/VA1d dendrites with the Mz19-Gal4 driver showed that they reside between ~3–6 μm in this high Vang expression domain. Vang staining in the neuropil begins to decline at 10 μm but strongly highlighted the nerve fiber layer (arrow) and the antennal nerve at 8–12 μm (arrow and arrowheads in Fig 2A and 2B), as well as the antennal commissure at 22 μm depth. The antibody stained the Vang6 mutant ALs (Fig 2C), likely because the Vang6 allele encodes a truncated protein. Nonetheless, the strong reduction in staining intensity compared with wild-type ALs attested to the antibody’s specificity. We concluded that Vang is expressed in the AL during the period of active AL neuropil rotation, where it colocalized with the DA1 and VA1d dendrites. The Vang expression pattern is consistent with the hypothesis that Vang mediates Wnt5 control of the DA1/VA1d dendritic rotation.

Fig 2. The Vang and Drl expression domains overlap with the developing DA1 and VA1d dendrites.

Frontal views of 24 hAPF ALs stained with Vang and Drl antibodies. (A, B) An AL from animals expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 stained with antibodies against Vang (Magenta) and CD8 (green) to highlight the DA1 and VA1d PN dendritic arbors. Between 0–9 μm from the anterior AL surface Vang is found in puncta, which are highly concentrated in the AL dorsolateral region where the DA1 and VA1d dendrites are localized (A1, A2). In deeper sections (8–12 μm) Vang is observed in the nerve fiber layer (arrow) and the antennal nerve (arrowhead) (B). (C) An AL from Vang6 mutants stained with antibodies against Vang (Magenta) and Drl (green) (C1). The AL stained poorly for Vang (C2) but strongly for Drl (C3) attesting to the specificity of the Vang antibody. (D, E) An AL from animals expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 stained with antibodies against Drl (Magenta) and CD8 (green). From 0–5 μm the Drl protein is concentrated in the lateral AL where it co-localizes with the DA1 dendrites (D1, D2). The VA1d dendrites are located medially and express a low level of the Drl protein. Deeper down (5–12 μm) the Drl protein is found in the dorsal and ventrolateral neuropil structures (E). (F) An AL from drl2 mutants stained with antibodies against Vang (Magenta) and Drl (green) (F1). The AL stained strongly for Vang (F2) but not at all for Drl (F3) attesting to the specificity of the Drl antibody. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Vang is required in the ORNs for DA1-VA1d dendritic rotation

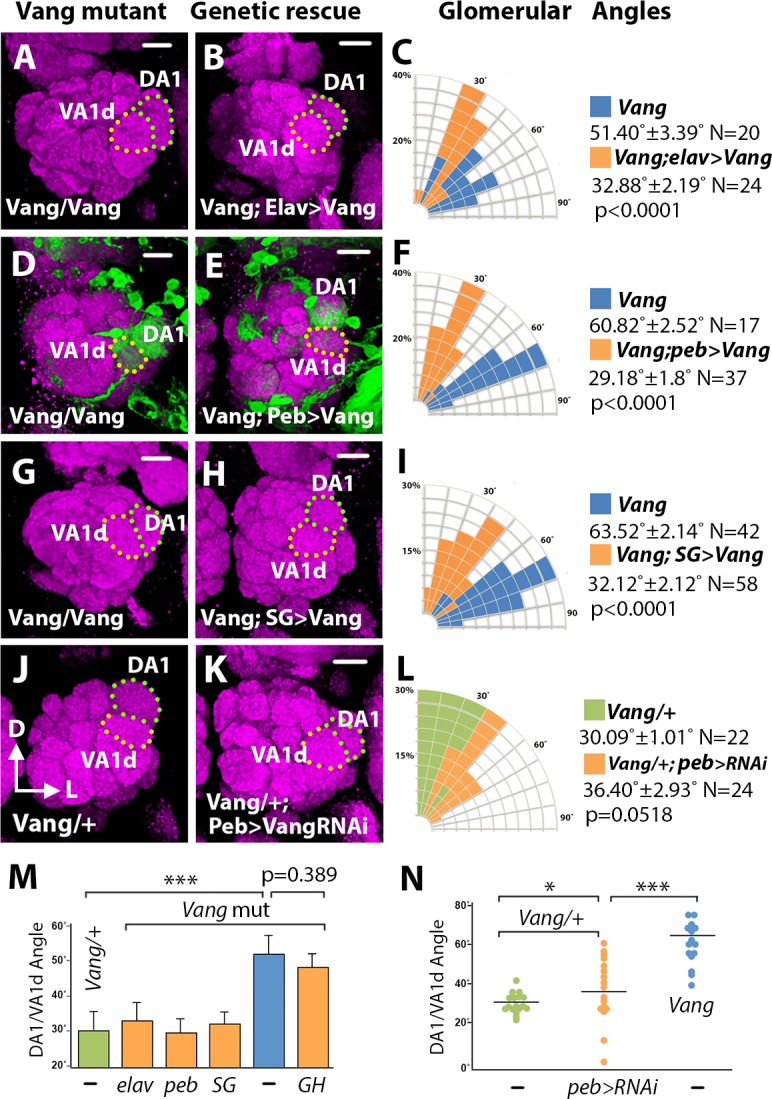

Since the Vang antibody strongly stained the AL nerve fiber layer, the antennal nerve and the antennal commissure, we hypothesized that Vang is expressed by ORNs and carried by axons to the developing AL. To identify the cell type in which Vang functions, we first used transgenic techniques to modulate Vang activity in specific cell types and examined the effect on the DA1/VA1d dendritic rotation. When we expressed the UAS-Vang transgene with the Elav-Gal4 pan-neuronal driver [25] in the Vang6 mutant, the DA1/VA1d dendritic angles became smaller (32.88˚ ± 2.19˚, N = 24) compared with that of the mutant control (51.40˚ ± 3.39˚, N = 20, t-test p<0.0001), indicating that Vang functions in neurons to promote dendritic rotation (Fig 3A–3C and 3M). When we expressed UAS-Vang using the ORN-specific drivers, peb-Gal4 and SG18.1-Gal4, the DA1/VA1d dendritic angles were also reduced (29.18˚ ± 1.6˚, N = 37 and 32.12˚ ± 2.12˚, N = 58 respectively) compared with that of the Vang6 mutant (60.82˚ ± 2.52˚, N = 17, peb rescue vs. Vang6, p<0.0001; SG18.1 rescue vs. Vang6, p<0.0001; peb rescue vs SG18.1 rescue, p = 0.8283; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test), indicating that Vang acts in the ORNs (Fig 3D–3I and 3M). In contrast, expression of UAS-Vang using a PN-specific driver, GH146-Gal4, did not significantly alter the DA1/VA1d rotational angles of the Vang6 mutant (47.87˚ ± 2.21˚, N = 39, t-test p = 0.3894; Fig 3M). In further support of Vang acting in the ORNs, when we drove the UAS-VangRNAi transgene [26] in the Vang6/+ heterozygote with peb-Gal4, the rotation of the DA1/VA1d dendritic angle increased slightly compared with that of the Vang6/+ heterozygote, indicating that Vang is required in the ORNs for DA1/VA1d dendritic rotation (36.40˚ ± 2.93˚, N = 24 compared with 30.09˚ ± 1.01˚, N = 22, t-test p = 0.0518) (Fig 3J–3L and 3N).

Fig 3. Vang functions in the ORNs to regulate glomerular migration.

Adult Vang6 ALs expressing Mz19-mCD8::GFP and different Vang transgenes were stained with antibodies against Brp (Magenta) and CD8 (green) to visualize the glomerular pattern. (A, B) Expression of UAS-Vang under the control of the pan-neuronal driver Elav-Gal4 in the Vang6 mutant (A) caused DA1 to migrate dorsally relative to the VA1d glomerulus (B). (C) Quantification of the DA1/VA1d glomerular angles in A and B. (D, E, G, H) Expression of UAS-Vang under the control of the ORN-specific drivers, peb-Gal4 (D, E) and SG18.1-Gal4 (G, H), also rescued DA1 dorsal migration. (F, I) Quantification of the DA1VA1d glomerular angles in D, E, G, and H. (J, K) Expression of UAS-VangRNAi under the control of the peb-Gal4 in the Vang6/+ mutant (J) slightly disrupted DA1 dorsal migration (K). (L) Quantification of the DA1VA1d glomerular angles in J and K. (M) Graph summarizing the glomerular angles in the rescue experiments. ANOVAs were used to simultaneously compare the Vang6 control and the rescued conditions. (N) Graph summarizing the glomerular angles in the VangRNAi knockdown experiment. With the exception of M, Student’s t tests were used to compare the data of the mutants with those of their respective controls. Scale bars: 10 μm.

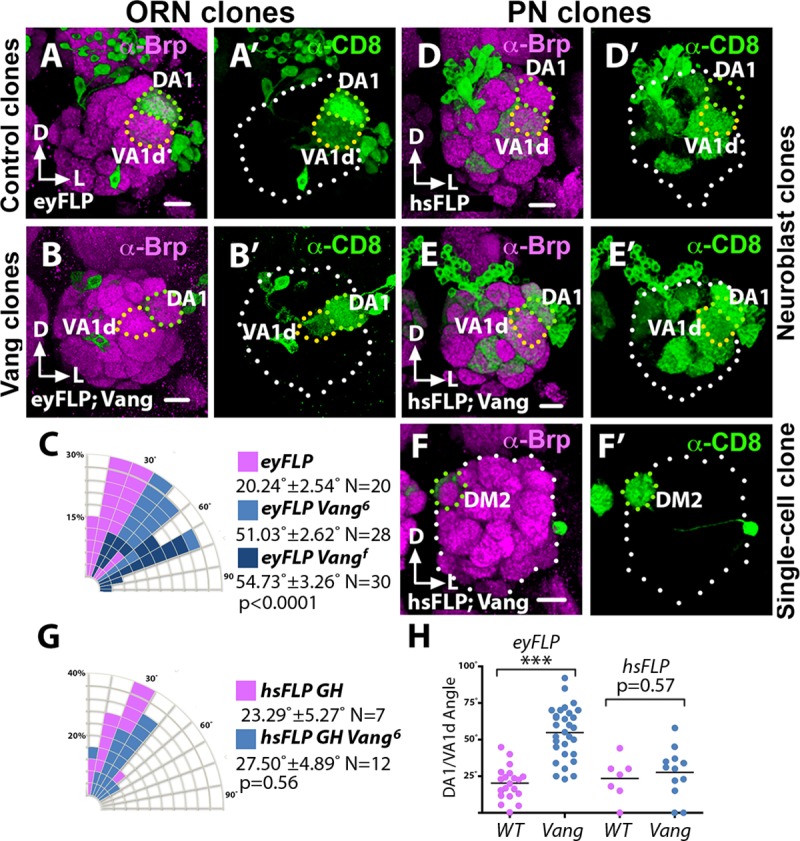

To confirm the above findings, we used mosaic techniques to induce ORNs or PNs lacking the Vang gene and examined the effects on the DA1/VA1d dendritic rotation. Induction of either Vangf04290 or Vang6 mutant ORN axons using the ey-FLP/FRT technique, which induces large clones in the antenna [27], resulted in the DA1/VA1d dendritic pair exhibiting larger angles (54.73˚ ± 3.26˚, N = 30 and 51.03˚ ± 2.62˚, N = 28 respectively) compared with animals innervated by wild-type ORN axons (20.24˚ ± 2.51˚, N = 20, wild type vs. Vangf04290, p<0.0001; wild type vs. Vang6, p<0.0001; Vang6 vs Vangf04290, p = 0.7297; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test) (Fig 4A–4C, 4G and 4H), confirming that Vang is required in the ORNs for DA1/VA1d dendritic rotation. Next, we induced Vang6 mutant PN clones using the MARCM system [28] with GH146-Gal4 as the PN marker. We observed that Vang6 mutant PN neuroblast and single-cell clones extended their dendrites into AL and innervated the glomeruli normally (Fig 4D–4F). Importantly, ALs innervated by large vang6 PN clones exhibited normal dendritic pattern, as judged by the angles of the DA1/VA1d dendrites (27.50˚ ± 4.89˚, N = 12) compared with those of the control (23.29˚ ± 5.27˚, N = 7, t-test p = 0.56) (Fig 4E, 4G and 4H). Thus, our transgenic rescue and mosaic experiments showed that Vang functions in the ORNs to non-autonomously promote the rotation of the DA1/VA1d dendritic pair.

Fig 4. Vang functions selectively in ORNs but not the PNs to regulate glomerular migration.

Vang6 and control mosaic ALs were stained with antibodies against Brp (Magenta) to visualize the glomerular pattern and CD8 (green) to visualize PN dendritic arborization. (A) In ALs innervated by wild-type ORN axon clones induced by the ey-FLP/FRT technique the DA1 glomerulus migrated normally relative to the VA1d glomerulus. (B) In ALs innervated by Vang6 mutant axon clones induced by the ey-FLP/FRT technique the DA1 glomerulus failed to migrate dorsally relative to the VA1d glomerulus. (C) Quantification of the glomerular angles in A and B. ANOVAs were used to simultaneously compare the control and the Vang6 and Vangf04290 conditions. (D) In ALs innervated by large clones of wild-type PN dendrites, induced by the MARCM technique the DA1 glomerulus migrated normally relative to the VA1d glomerulus. (E, F) In ALs innervated by neuroblast (E) and single-cell (F) clones of Vang6 PN dendrites induced by the MARCM technique, the mutant dendrites innervated the AL normally and the DA1 glomerulus migrated normally relative to the VA1d glomerulus. (G) Quantification of the glomerular angles in D, E and F. Student’s t test was used to compare the data of the mutant clones with that of the controls. (H) Graph summarizing the glomerular angles in the mosaic control and Vang6 ALs. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Vang is not required for ORN axon growth or correct ORN-PN pairing

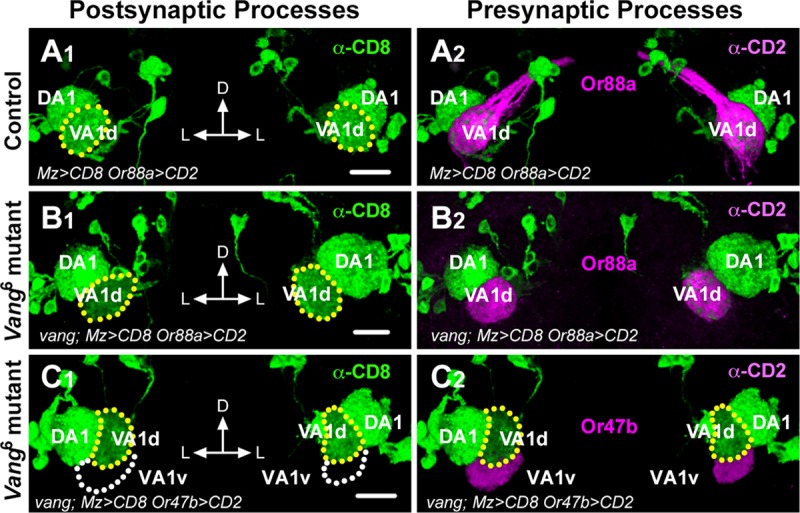

A possible explanation for the Vang mutant phenotype is that Vang is required for ORN axon growth to the AL, the failure of which indirectly disrupted glomerular patterning. Mutations in Vang have been shown to result in abnormal projection of mushroom body axons [29]. To determine if ORN axons entered the AL in the Vang6 mutant, we labeled eight different ORN axon terminals in the AL using Or-Gal4 drivers. We found that Vang6 mutant axons entered the AL normally, although their terminals were shifted in the AL neuropil (Fig 1). To investigate if the Vang mutation disrupted the proper matching of the ORN axons and PN dendrites, we simultaneously labeled pre- and postsynaptic partners of glomeruli for which specific markers were available. We achieved this by labeling the DA1, VA1d and DM1 dendrites with Mz19-Gal4 driving UAS-mCD8::GFP and simultaneously the ORN axons targeting the VA1d and VA1v glomeruli with the Or88a-CD2 and Or47b-CD2 transgenes respectively. We observed that Or88a axons were strictly paired with VA1d PN dendrites in the Vang6 mutant as in the wild type (Fig 5A and 5B). Likewise, the Or47b axons strictly innervated the VA1v glomerulus, and never strayed into the VA1d territory in the Vang6 mutant (Fig 5C). Thus, Vang is not required for ORN axon projection into the AL or their correct pairing with their postsynaptic partners. We propose that Vang functions in the context of paired axons and dendrites allowing the neurites to coordinately respond to the Wnt5 signal. This idea is consistent with our observation that PN dendritic rotation occurs between 16 and 30 hAPF [11], the period of major ORN axon invasion into the AL [8, 12].

Fig 5. Vang does not function in ORN axon projection or pairing with cognate PN dendritic partners.

(A, B) Adult brains from animals expressing Or88a-CD2 and UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 were stained with anti-CD2 (magenta) and anti-CD8 (green) to visualize the pre- and postsynaptic processes of the VA1d and VA1v glomeruli. In the wild-type control, Or88a axons are faithfully paired with the VA1d dendrites (A). Collaterals form a fascicle, which innervates the contralateral AL. In the Vang6 mutant, Or88a axons are also faithfully paired with the VA1d dendrites (B). Vang mutant axons fail to sprout collaterals as previously reported [29]. (C) Frontal views of adult ALs from Vang6 mutants expressing Or47b-CD2 and UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 stained with anti-CD2 (magenta) and anti-CD8 (green). In the mutant, Or47b axons targeted the adjacent VA1v glomerulus without straying into the VA1d glomerular territory. Scale bar: 10 μm.

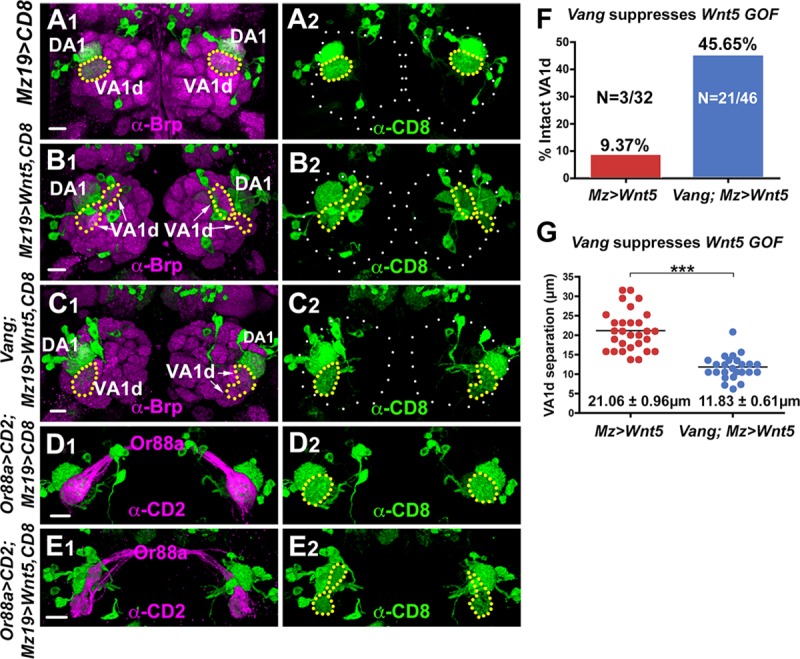

Vang acts downstream of Wnt5 to repel the VA1d glomerulus

The close resemblance of the Vang and Wnt5 mutant phenotypes raised the questions of whether and how Vang might function in the Wnt5 signaling pathway to regulate the rotation of the DA1 and VA1d glomeruli. To address these questions, we asked if loss of Vang would block Wnt5 signaling. We previously showed that overexpression of Wnt5 in the DA1 and VA1d dendrites with the Mz19-Gal4 driver split the VA1d dendrites into two smaller arbors probably due to repulsion between the dendrites (Fig 6A and 6B) [11]. Interestingly, Wnt5 overexpression had no effect on the DA1 dendrites, indicating that the DA1 and VA1d dendrites respond differentially to the Wnt5 signal. The VA1d defect provided an opportunity to assess if Vang is needed for the Wnt5 gain-of-function phenotype. Whereas only 9.37% (3/32) of the VA1d dendrites in the Mz19>Wnt5 animals were intact, this fraction rose to 45.65% (21/46) in the Mz19>Wnt5; Vang6/Vang6 animals (Fig 6C and 6F). Moreover, the distances between the split VA1d arbors in the Mz19>Wnt5; Vang6/Vang6 animals were smaller than those in the Mz19>Wnt5 animals (11.83 μm ± 0.61 μm, N = 25, vs 21.06 μm ± 0.96 μm, N = 29, t-test p<0.0001) (Fig 6B, 6C and 6G). Despite severe distortion, the VA1d dendrites were faithfully paired with their Or88a axon partners, reinforcing the idea that Wnt5 signaling does not play a role in ORN-PN matching (Fig 6D and 6E). Overexpression of Wnt5 in the DA1 and VA1d dendrites did not affect the development of the Or88a neurons (S2 Fig). We conclude that Wnt5 signals through Vang to repel the VA1d glomerulus.

Fig 6. Vang functions downstream of Wnt5 to cell non-autonomously repel the VA1d dendrites.

(A-C) Adult ALs from animals expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 were stained with antibodies against Brp (magenta) to visualize the glomerular pattern and CD8 to visualize the DA1/VA1d dendrites (green). (A) In the wild-type control, the DA1 dendrites are located dorsal to the VA1d dendrites, which form a single compact arbor. (B) In animals expressing UAS-Wnt5 under the control of Mz19-Gal4, the VA1d dendrites split into two separated arbors, probably due to repulsion between the dendritic branches. (C) Removing Vang functions in animals expressing UAS-Wnt5 under the control of Mz19-Gal4 return the VA1d dendrites to its compact morphology in the right AL. In the left AL, the two separated branches are closer together. (D, E) Adult ALs from animals expressing Or88a-CD2 and UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 were stained with anti-CD2 (magenta) and anti-CD8 (green) to visualize the pre- and postsynaptic processes of the VA1d glomerulus. In the wild-type control, Or88a axons are faithfully paired with the VA1d dendrites (D). In animals expressing UAS-Wnt5 under the control of Mz19-Gal4 the Or88a axons were still correctly paired with the VA1d dendrites despite their splitting into two separated arbors (E). (F) Graph summarizing the percentage of intact VA1d glomeruli in wild-type and Vang6 animals overexpressing Wnt5 in the VA1d glomeruli. (G) Graph summarizing the distance between the split VA1d arbors in wild-type and Vang6 animals overexpressing Wnt5 in the VA1d glomeruli. Student’s t test was used to compare the data of the wild-type and Vang6 animals overexpressing Wnt5. Scale bars: 10 μm.

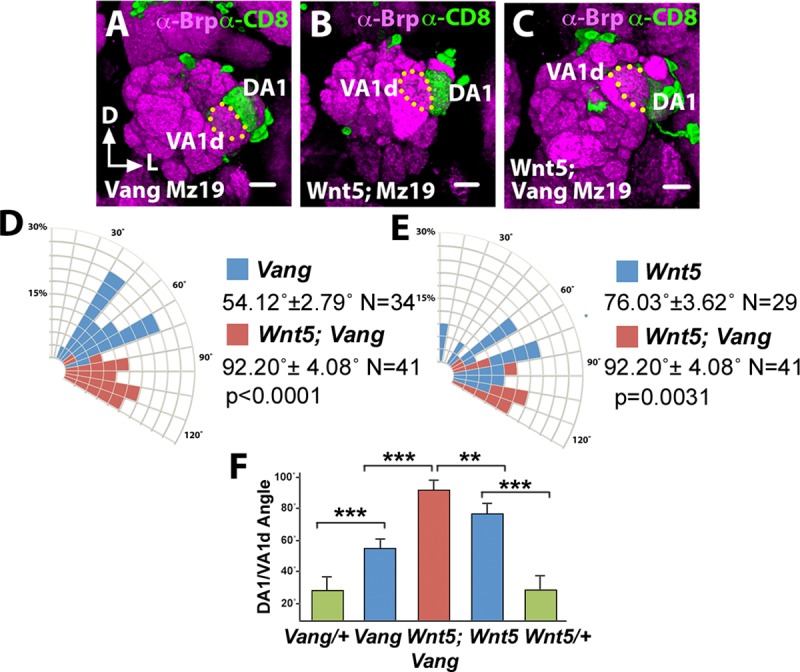

To further probe the relationship between Wnt5 and Vang, we examined the DA1/VA1d rotation in animals lacking both genes. We observed that the rotation in the Wnt5400; Vang6 double mutant (92.20˚ ± 4.1˚, N = 41) is more severely disrupted than that in either single mutant (76.03˚ ± 3.62˚ in Wnt5400, n = 29, t-test p = 0.0031 and 54.12˚ ± 2.8˚ in Vang6, n = 34, t-test p<0.0001) (Fig 7). The enhanced phenotype of the Wnt5400; Vang6 mutant suggested that Wnt5 and Vang could function independently to promote DA1/VA1d rotation (Fig 7F). We currently do not know how Vang acts independently of Wnt5. However, it interesting that Wnt5 directs the rotation of the DA1/VA1d glomeruli through both Vang-dependent and Vang-independent pathways. Since Wnt5 acts through Vang in the VA1d glomerulus, we hypothesized that Wnt5 acts through a Vang-independent mechanism in the DA1 glomerulus.

Fig 7. Wnt5 and Vang could function independently to regulate DA1/VA1d glomerular rotation.

(A-C) Frontal views of adult ALs from animals expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 stained with antibodies against Brp (magenta) and CD8 (green) to visualize the glomerular pattern and the DA1/VA1d dendrites respectively, in the Vang6 (A), Wnt5400 (B) and Wnt5400; Vang6 (C) mutants. (D) Quantification of the DA1/VA1d angles in panels A and C showing that the rotational defect is stronger in the Wnt5400; Vang6 mutant than in the Vang6 mutant. (E) Quantification of the DA1/VA1d angles in B and C showing that the rotational defect is stronger in the Wnt5400; Vang6 mutant than in the Wnt5400 mutant. (F). Graph summarizing the DA1/VA1d angles in the Vang6 and Wnt5400 single mutants and Wnt5400; Vang6 double mutant. Student’s t tests were used to compare the angles of the various mutants. Scale bars: 10 μm.

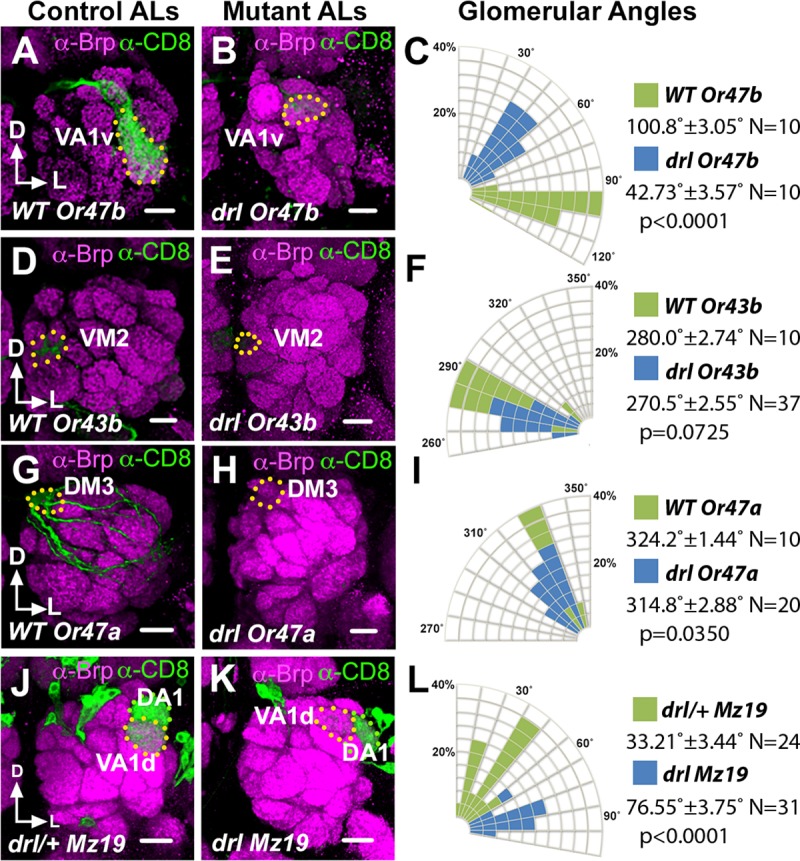

drl promotes the rotation of DA1-VA1d glomeruli

The Drl atypical receptor tyrosine kinase has been shown to bind Wnt5 and mediates its signaling in the migration of a number of cell types [14–17]. We previously demonstrated that Drl is differentially expressed by PN dendrites wherein it antagonizes Wnt5’s repulsion of the dendrites [11]. To delineate the AL region where drl functions, we examined the positioning of several glomeruli in the null drl2 mutant by expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of various Or-Gal4 drivers (Fig 8A–8I). We observed that, as in the Vang mutant, the lateral glomeruli showed the strongest displacements in positions compared with the control indicating that drl primarily regulates neurite targeting in the lateral AL (Fig 8A–8C). To better characterize the neuropil defect in this region we employed the Crispr/Cas9 technique [30] to create the null drlJS allele on the Mz19-Gal4 chromosome (Materials and Methods), which allowed us to assess the DA1/VA1d dendritic arrangement in the drl mutant. To our surprise, we observed that the DA1/VA1d dendritic pair in the drlJS/drl2 null mutant showed strong deficits in DA1/VA1d rotation, resembling the Wnt5400 null phenotype (Fig 8J–8L). Indeed, measurement of the DA1/VA1d angle of the drlJS/drl2 mutant (76.55˚ ± 3.75˚, N = 31) showed that it was even slightly larger than that of the Wnt5400 mutant (69.22˚ ± 5.03˚, N = 32, t-test p = 0.2493). The similarity of the drl and Wnt5 mutant phenotypes indicates that drl cooperates with Wnt5 in promoting the rotation of the DA1/VA1d glomeruli.

Fig 8. The drl2 mutant AL defects resemble that of the wnt5400 mutant.

(A-I) Left adult ALs from wild-type (A, B, G) and drl2 (B, E, H) animals expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Or47b-Gal4 (A, B), Or43b-Gal4 (D, E) and Or47a-Gal4 (G, H) were stained with antibodies against Brp (Magenta) to highlight the AL neuropil and CD8 (green) to label lateral, medial and dorsal glomeruli respectively. (C, F, I) Quantification of the positions of the Or47b, Or43b and Or47a glomeruli respectively in the wild-type vs drl2 animals. The glomeruli appeared to be displaced in the counterclockwise direction in the drl2 mutant with VA1v showing the greatest displacement. (J, K) ALs from adult drlJS/+ control (J) and drlJS/drl2 animals (K) expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 were stained with antibodies against Brp (Magenta) and CD8 (green) to highlight the AL neuropil and the DA1/VA1d PN dendritic arbors respectively. (L) Quantification of the DA1/VA1d angles in the drlJS/drl2 mutant. The DA1 dendrites are located lateral to the VA1d dendrites in the drlJS/drl2 mutant reflecting a severe impairment in DA1/VA1d dendritic rotation. This phenotype resembles that of the Wnt5400 mutant. Student’s t tests were used to compare the data of the drl mutants with those of the controls. Scale bars: 10 μm.

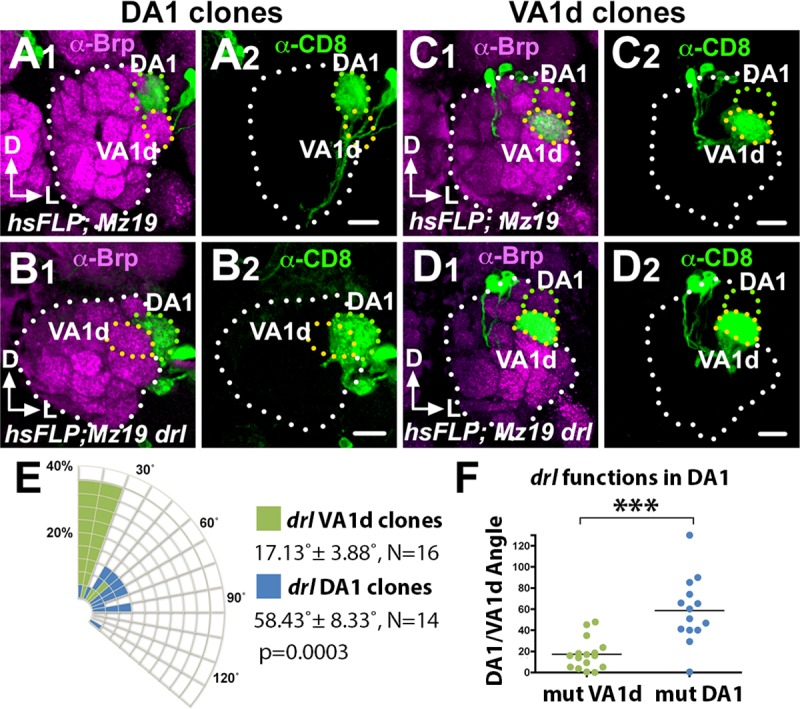

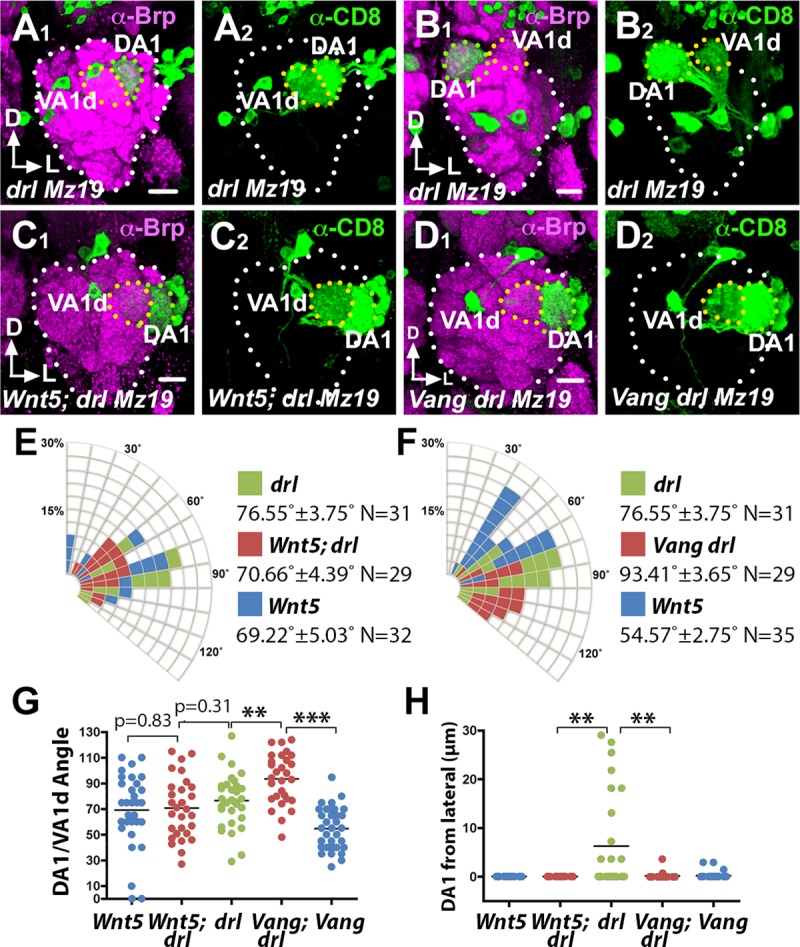

drl acts in the DA1 dendrites to promote glomerular attraction to Wnt5

How does drl mediate Wnt5 function in glomerular rotation? We hypothesized that drl functions in the DA1 dendrites, to regulate migration of the DA1 glomerulus towards the Wnt5 source. In support of this idea, antibody staining of the Drl protein showed that it is highly expressed by the DA1 dendrites but not the VA1d dendrites (Fig 2D and 2E) [11]. The domain of high Drl expression occupies the anterior dorsolateral domain of the 24 hAPF ALs (0–8 μm from anterior), a region in which Wnt5 is also highly expressed [11]. The hypothesis predicts that ablation of drl in DA1 alone would disrupt the rotation of the DA1/VA1d glomeruli. To test this hypothesis, we used MARCM to induce drlJS homozygosity in either DA1 or VA1d dendrites and assessed the effects on DA1/VA1d glomerular rotation. The DA1 and VA1 dendrites could be independently identified since their cell bodies are located in the lateral and anterodorsal PN clusters respectively. We observed that drlJS mutant VA1d dendrites were associated with glomerular pairs with small angles (17.13˚ ± 3.68˚, N = 16), that is, with the DA1 glomerulus closely associated with the dorsolateral AL (Fig 9C–9F). In contrast, drlJS mutant DA1 dendrites are associated with glomeruli with wide variations in angles (58.43˚ ± 8.33˚, N = 14, t-test p = 0.0003), that is, with the DA1 glomerulus not closely associated with the dorsolateral AL (Fig 9A, 9B, 9E and 9F). Thus, drl appears to act in the DA1 dendrites to confer directionality of the DA1 glomerulus towards the Wnt5 source.

Fig 9. drl functions in the DA1 dendrites but not VA1d dendrites to promote DA1/VA1d glomerular rotation.

Mosaic control and drlJS ALs generated by the MARCM technique were stained with antibodies against Brp (Magenta) to visualize the glomerular pattern and CD8 (green) to visualize the clonal PN dendrites. (A) Control DA1 dendrites are often observed in DA1/VA1d glomerular pair with small rotational angles. (B) In contrast, drlJS mutant DA1 dendrites are frequently observed in DA1/VA1d glomeruli with large rotational angles indicating impaired glomerular rotation. (C) Control VA1d dendrites are often observed in DA1/VA1d glomerular pair with small rotational angles. (D) Likewise, drlJS mutant VA1d dendrites are frequently observed in DA1/VA1d glomerular pair with small rotational angles indicating normal glomerular rotation. (E) Quantification of the glomerular angles of the drlJS mutant DA1 and VA1d clones. (F) Graph summarizing the drlJS DA1 vs VA1d clonal data. Student’s t test was used to compare the data of the drl DA1 vs VA1d mutant clones. Scale bars: 10 μm.

drl likely converts Wnt5 repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus into attraction

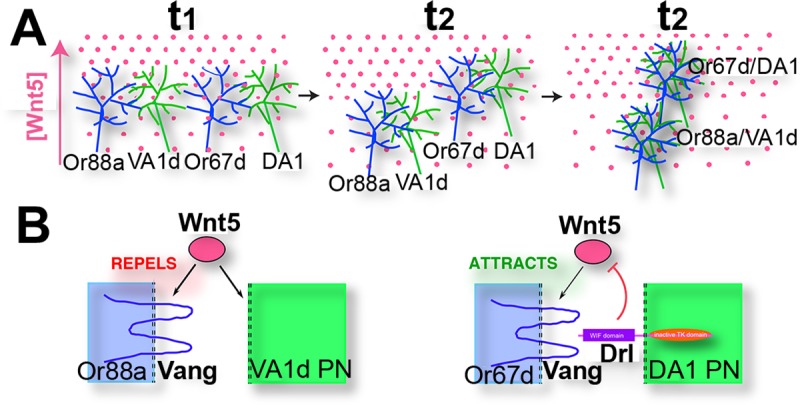

How does drl promote the migration of the DA1 glomerulus towards Wnt5? We propose two models by which drl could accomplish this task. In the first model, drl acts as a positive effector of Wnt5 attractive signaling. In the second model, drl neutralizes Wnt5 repulsive signaling and/or converts the repulsive signaling into an attractive one. Careful examination of the DA1/VA1d targeting defects in drlJS/drl2 null mutant revealed differences with that of the Wnt5400 mutant, inconsistent with the idea that drl acts as a positive effector of Wnt5 signaling. First, the DA1 glomerulus is often displaced medially from the AL lateral border (6.26 μm ± 1.85 μm from border, N = 28) (Fig 10H), a defect not seen in the Wnt5400 mutant. This resulted in the frequent reversal in the positions of the DA1 and VA1d glomeruli (Fig 10B), or displacement of both glomeruli medially from the AL lateral border (Fig 10A). Second, the mean DA1/VA1d angle in the drlJS/drl2 null mutant is slightly but not significantly larger than that of Wnt5400 null mutant (Fig 10E and 10G). Instead the defects are more consistent with the second model, which predicts increased Wnt5 repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus in the drl mutant, thus driving the glomerulus ventromedially. To test this hypothesis, we simultaneously removed both drl and Wnt5 functions and examined the displacement of the DA1/VA1d glomeruli. We observed that the DA1 glomerulus is restored to AL lateral border in the Wnt5400; drlJS/drl2 double mutant, as it is in the Wnt5 homozygote (0.00 μm from border, N = 30 and N = 25 respectively) (Fig 10C and 10H). We also observed that the DA1/VA1d angle in the Wnt5; drl double mutant (70.66˚ ± 4.39˚, N = 29) is more similar to that of the Wnt5 mutant (69.22˚ ± 5.03˚, N = 32, t-test p = 0.83) than that of the drl mutant (76.55˚ ± 3.75˚, N = 31, t-test p = 0.3102) (Fig 10E and 10G). We conclude that Wnt5 repels the DA1 glomerulus ventromedially and that drl antagonizes the Wnt5 repulsive activity. Since we showed above that drl promotes the migration of DA1 towards Wnt5, we conclude that drl acts in the DA1 glomerulus to convert Wnt5 repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus into attraction. Taken together, our results suggest that Wnt5 orients the rotation of the VA1d/DA1 glomeruli by attracting the DA1 glomerulus through Wnt5-drl signaling and repelling the VA1d glomerulus through Wnt5-Vang signaling.

Fig 10. Wnt5 repels the DA1 glomerulus through Vang, a function that drl antagonizes.

Left adult ALs of animals expressing UAS-mCD8::GFP under the control of Mz19-Gal4 were stained with nc82 (magenta) and anti-CD8 (green) to visualize the neuropil and the DA1/VA1d dendrites respectively. (A, B) In the drl mutant, the DA1 glomerulus was often displaced from the AL lateral border, resulting in the medial shift of the DA1/VA1d glomerular pair (A) or a reversal in the positions of the two glomeruli (B). (C) The loss of the wnt5 gene suppressed the DA1 medial displacement, restoring the DA1 glomerulus to the AL lateral border, indicating that drl antagonizes Wnt5 repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus. (D) The DA1 medial displacement is also suppressed by the loss of the Vang gene, suggesting that Vang functions in Wnt5 repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus. In addition, the DA1/VA1d glomerular angle of the drl mutant is large. (E) Quantification of the DA1/VA1d glomerular angles in the drl and Wnt5 single mutants and Wnt5; drl double mutant. (F) Quantification of the DA1/VA1d glomerular angles in the drl and Vang single mutants and Vang drl double mutant. (G) Graph summarizing the DA1/VA1d glomerular angles in the drl, Wnt5, and Vang mutants. (H) Graph summarizing the distance of the DA1 glomerulus from the AL lateral border in the drl, Wnt5, and Vang mutants. Student’s t tests were used to compare the data of the double mutants with the single mutants. Scale bars: 10 μm.

To investigate the mechanism by which drl converts Wnt5 repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus into attraction, we examined the mechanism by which Wnt5 repels the DA1 glomerulus. A likely scenario is that Wnt5 repels the DA1 glomerulus through Vang. To test this idea, we simultaneously removed both drl and Vang functions and measured the displacement of the DA1 glomerulus from the AL lateral border as well as the DA1/VA1d rotational angle. We found that in the Vang6 drlJS/Vang6 drl2 double mutant, the DA1 glomerulus is restored to the AL lateral border (0.156 μm ± 0.132 μm, N = 28, t-test p = 0.0017) (Fig 10D and 10H). We conclude that drl neutralizes the Wnt5-Vang repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus. Interestingly, measurement of the DA1/VA1d angles in the Vang drl double mutant showed that the rotation of the glomeruli is more severely impaired (93.41˚ ± 3.65˚ N = 29) than that of either single mutants (76.55˚ ± 3.75˚ in drl2, N = 31, t-test p = 0.0021 and 54.57˚ ± 2.75˚ in Vang6, N = 35, t-test p<0.0001) (Fig 10F and 10G). The enhanced phenotype of the Vang drl double mutant indicated that drl and Vang act in parallel pathways to promote DA1/VA1d rotation. The parallel functions are in accord with our model that drl acts in the DA1 glomerulus while Vang acts in the adjacent VA1d glomerulus to promote DA1/VA1d rotation. Simultaneous loss of Vang and drl would be expected to exacerbate the DA1/VA1d rotational defect.

Discussion

Elucidating the mechanisms that shape dendritic arbors is key to understanding the principles of nervous system assembly. Genetic approaches have revealed both intrinsic and extrinsic cues that regulate the patterning of dendritic arbors [31, 32]. In contrast, there are only a few reports on the roles of axons in shaping dendritic arborization [33, 34]. In this paper we provide evidence that final patterning of the fly olfactory map is the result of an interplay between ORN axons, PN dendrites and the Wnt5 directional signal (Fig 11). We show that the Vang PCP protein [20, 21] is an axon-derived factor that mediates the Wnt5 repulsion of the VA1d dendrites. We also show that the Drl protein is specifically expressed by the DA1 dendrites where it antagonizes the Wnt5-Vang repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus and likely converts it into an attractive response. The differential responses of the DA1 and VA1d glomeruli to Wnt5 would produce the forces by which Wnt5 effects the rotation of the glomerular pair. We present the following lines of evidence in support of this model of olfactory neural circuit development.

Fig 11. Model for the Wnt5-directed rotation of developing glomeruli.

(A) The targeting of two ORN axons (Or88a and Or67d) on their respective PN dendritic partners (VA1d and DA1) in the Wnt5 gradient at three time points is depicted. At time t1, the pre- and postsynaptic processes have not paired up and the individual neurites do not respond to the Wnt5 signal. At time t2, the neurites are beginning to pair up, which allows the nascent synapses to respond to the Wnt5 signal. (B) The Or88a:VA1d glomerulus is repelled by Wnt5 because the VA1d dendrite does not express Drl. On the other hand, the Or67d:DA1 glomerulus is attracted by Wnt5 because the DA1 dendrite expresses Drl, which converts Wnt5-Vang repulsion into attraction. Repulsion of the Or88a:VA1d glomerulus causes it to move down the Wnt5 gradient while the attraction of the Or67d:DA1 glomerulus causes it to move up the Wnt5 gradient. At time t3, the ORN axons and PN dendrites have fully condensed to form glomeruli. The opposing responses of the glomeruli to Wnt5 result in their rotation around each other.

Immunostaining showed that Vang is expressed at the same time and place as Wnt5 and Drl, and concentrated in the dorsolateral AL where major dendritic reorganization occurs [11]. Mutations in Vang strongly disrupted the pattern of glomeruli in the AL, mimicking the Wnt5 mutant phenotype. Notably, mutation of Vang suppressed the strong repulsion of the VA1d dendritic arbor caused by Wnt5 overexpression, indicating that Vang acts downstream of Wnt5 to repel the VA1d dendrites. Unexpectedly, using cell type-specific transgenic experiments and mosaic analyses we found that Vang functions specifically in the ORNs, indicating an obligatory codependence of ORN axon and PN dendritic targeting. Unlike the VA1d glomerulus, which expresses low levels of drl and is repelled by Wnt5, the adjacent DA1 glomerulus expresses high levels of drl. Mosaic analyses showed that drl acts specifically in the DA1 dendrites to confer directionality of the DA1 glomerulus towards Wnt5. Finally, in the absence of drl, the DA1 glomerulus is displaced away from the Wnt5 source, a defect that is suppressed by the removal of either Wnt5 or Vang. Taken together, we propose that drl likely converts Wnt5 repulsion of the DA1 glomerulus into attraction by inhibiting Wnt5-Vang repulsive signaling.

We envision that Vang and Drl act cell autonomously to regulate axonal and dendritic guidance respectively and cell non-autonomously to modulate each other’s functions. Both Vang and Drl/Ryk have well-documented cell autonomous functions in neurite guidance. For example, vertebrate Vangl2 was localized to the filopodia of growth cones [35, 36] and Drosophila Vang mediates the repulsion of mushroom body axon branches in respond to Wnt5 [29, 37]. Similarly, Drl and Ryk mediate the functions of Wnt5 and Wnt5a respectively in the targeting of dendrites [16, 38] and axons [5, 14, 17, 39, 40]. Both proteins also have well-documented cell non-autonomous functions. Vertebrate Vangl2 acts as a ligand to steer migrating neurons [41, 42]. We and others have shown that Drl could sequester Wnt5 using its extracellular Wnt Inhibitory Factor (WIF) motif [38, 43–45]. Indeed, in this manner Drl may reduce Wnt5-Vang interaction, thus neutralizing Wnt5 repulsion of the glomeruli. How would Drl convert a glomerulus’s response to Wnt5 from repulsion to attraction? Increasing Ryk levels were proposed to titrate out Fz5 in chick retinal ganglion axons, thus converting growth cone response to Wnt3 from attraction to repulsion [46]. Whether Drl function through a similar mechanism in the DA1 dendrites will require further investigation.

The opposing functions of Vang and Drl in a migrating glomerulus satisfies Geirer’s postulate for topographic mapping, which states that targeting neurites must detect two opposing forces in the target so that each neurite would come to rest at the point where the opposing forces cancel out [47]. Thus, the relative levels of Drl and Vang activities in a glomerulus may determine its targeting position in the Wnt5 gradient (Fig 11). For the DA1/VA1d glomerular pair, the relative levels of Drl and Vang activities would result in the migration of DA1 up the gradient and VA1d down the gradient, that is, the rotation of the glomerular pair. The opposing effects of Wnt5 on the targeting glomeruli could allow the single Wnt5 gradient to refine the pattern of the olfactory map.

The rotation of the DA1/VA1d glomeruli bears intriguing resemblance to the PCP-directed rotation of multicellular structures such as mouse hair follicles and fly ommatidia, whose mechanisms remain incompletely understood [48–50]. Our demonstration of the push-pull effect of Wnt5 on the glomeruli suggests that similar mechanisms may be involved in other PCP-directed rotations. Planar polarity signaling has emerged as an important mechanism in the morphogenesis of many tissues [20, 51, 52]. However, apart from the molecules of the core PCP group (Vang, Prickle, Frizzled and Dishevelled) the identities of other signaling components are subjects of debate. A key question is the extracellular cue that aligns the core PCP proteins with the global tissue axes. Although Wnt ligands have been implicated, a definitive link between them and PCP signaling has been difficult to establish [20, 21, 53]. Our work showing that Wnt5 and Vang act together to direct the orientation of nascent glomeruli adds to two other reports [54, 55] that Wnt proteins play instructive roles in PCP signaling. Another debate surrounds the role of Drl/Ryk role in PCP signaling. First identified as signal transducing receptors for a subset of Wnt ligands in Drosophila [17, 56], vertebrate Ryk was subsequently shown to act in PCP signaling [57, 58]. These reports, combined with the lack of classical wing-hair PCP phenotypes in the drl mutant, led to the proposal that Ryk’s PCP function is a vertebrate innovation [59]. Our demonstration of drl’s role in Wnt5-Vang signaling suggests, however, that the Drl/Ryk’s PCP function is likely to be evolutionarily ancient.

Materials and methods

Fly strains and Crispr/Cas9 knockout of the drl gene

All mutant and transgenic fly lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center except for UAS-Vang, which was a gift from B. A. Hassan. The Wnt5400 allele is a null allele generated by the imprecise excision of an adjacent P element, resulting in the deletion of most of the Wnt5 open reading frame [14]. The drl2 allele is a null allele generated by the imprecise excision of a P element in the 5’ non-coding region, resulting in the deletion of the 5’ regulatory sequences and the first exon of drl [60]. To generate a new drl null allele on the Mz19-Gal4 chromosome, exons 2, 3 and 4 of the drl locus (encompassing ~90% of the drl open reading frame) were excised from the chromosome by Crispr/Cas9-mediated deletion using the sgRNAs GACAAGTGAAGGGGTGCTGT and GACACCTGTAGTGAGAGGTA following a published protocol [61]. Ten individual offspring from Crispr/Cas9 fathers were crossed to Adv/CyO virgins to establish lines. The lines were screened by PCR using deletion-spanning primers to identify potential drl mutants. The PCR products were sequenced and one mutant, drlJS, with the expected precise deletion of the drl locus in the Mz19-Gal4 background was chosen for study. The drlJS mutation failed to complement the AL phenotype of the drl2 mutation, consistent with drlJS being a null allele.

Clonal analyses

To induce Vang mutant ORNs, adults of the following genotype, ey-FLP/+; FRT42 w+ cl/Mz19-Gal4 FRT42 Vang6 or (+), were obtained and dissected. To induce Vang and drl mutant PNs, the MARCM technique was employed [28]. Third instar larvae of the following genotypes: hs-FLP UAS-mCD8::GFP/+; FRT42 tub-Gal80/FRT42 GH146-Gal4 Vang6 or (+) and hs-FLP UAS-mCD8::GFP/+; FRT40 tub-Gal80/FRT40 Mz19-Gal4 drlJS or (+); UAS-mCD8::GFP/+ were heat-shocked at 37˚C for 40 minutes. Adult brains were dissected and processed as described below.

Immunohistochemistry

Dissection, fixing and staining of adult or pupal brains were performed as previously described [27, 62]. Rabbit anti-DRL (1:1000) was a generous gift from J. M. Dura; rat anti-Vang (1:500) was a gift from D. Strutt; mAb nc82 (1:20) [63] was obtained from the Iowa Antibody Bank; rat anti-mCD8 mAb (1:100) was obtained from Caltag,. The secondary antibodies, FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat, were obtained from Jackson Laboratories and used at 1:100 dilutions. The stained brains were imaged using a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope

Quantification of glomerular rotation

Two different quantification strategies were employed. To quantify the displacements of single glomeruli labeled by the Or-Gal4 drivers [6], the angle subtended at the VA6 glomerulus (close to the center of the AL) by the dorsal pole and the labeled glomerulus (in the dorsal/0˚ → lateral/90˚ → ventral/180˚ → medial direction/270˚) was measured. To quantify the rotation of the DA1 and VA1d glomeruli [22] around each other, the angle subtended at the VA1d glomerulus by the dorsal pole and the DA1 glomerulus (in the dorsal/0˚ → lateral/90˚ → ventral/180˚ → medial/270˚ direction) was measured. Data were collected, analyzed and plotted using the Prism statistical software. For two-sample comparisons, unpaired Student’s t-tests were applied. For comparisons among more than two groups, one-way AVOVA tests were used followed by Tukey’s test. Rose diagrams were plotted using the Excel program.

Supporting information

Schematic representations of the frontal views of left ALs are shown (dorsal/0˚ is up and lateral/90˚ is to the right). A line was drawn through the centers of the DA1 and VA1d glomeruli. Where the line intersects with the dorsal-ventral axis, the angle in the clockwise direction from 0˚ was measured. During development, the DA1/VA1d angle decreases because the two glomeruli rotate around each other in the counterclockwise direction.

(TIF)

Frontal views of adult left antennae are shown (dorsal up and lateral to the right. (A-C) Representative freshly dissected antennae from animals expressing Or88a-mGFP were imaged using the confocal microscope to visualize the live Or88a neurons in the wild-type (A), Wnt5400 (B), and Mz19-Gal4 UAS-Wnt5 (C) animals. (D) Quantification of the Or88a neuronal numbers in the different genotypes. The numbers of Or88a neurons in the Wnt5400 (41.22 ± 2.681, N = 9) mutant and Mz19-Gal4 UAS-Wnt5 (32.00 ± 1.535, N = 8) overexpression animals are similar to those in the Wild type (33.17 ± 0.8776, N = 12). Wild type vs Wnt5400, p = 0.0060; Wild type vs Mz19-Gal4 UAS-Wnt5, p = 0.8834; Wnt5400 vs Mz19-Gal4 UAS-Wnt5, p = 0.0043; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Luo and the Bloomington Stock Center for providing fly stocks, J. M. Dura and D. Strutt for their generous gifts of the anti-Drl and anti-Vang antibodies respectively, and J. N. Noordermeer and J. M. Dura for their comments on the paper.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NIDCD (DC010916-02A1) awarded to HH. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hong W, Luo L. Genetic control of wiring specificity in the fly olfactory system. Genetics. 2014;196(1):17–29. 10.1534/genetics.113.154336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo L, Flanagan JG. Development of continuous and discrete neural maps. Neuron. 2007;56(2):284–300. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLaughlin T, O'Leary DD. Molecular gradients and development of retinotopic maps. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:327–55. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakano H. Neural map formation in the mouse olfactory system. Neuron. 2010;67(4):530–42. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarin S, Zuniga-Sanchez E, Kurmangaliyev YZ, Cousins H, Patel M, Hernandez J, et al. Role for Wnt Signaling in Retinal Neuropil Development: Analysis via RNA-Seq and In Vivo Somatic CRISPR Mutagenesis. Neuron. 2018;98(1):109–26 e8. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couto A, Alenius M, Dickson BJ. Molecular, anatomical, and functional organization of the Drosophila olfactory system. Curr Biol. 2005;15(17):1535–47. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishilevich E, Vosshall LB. Genetic and functional subdivision of the Drosophila antennal lobe. Curr Biol. 2005;15(17):1548–53. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jefferis GS, Vyas RM, Berdnik D, Ramaekers A, Stocker RF, Tanaka NK, et al. Developmental origin of wiring specificity in the olfactory system of Drosophila. Development. 2004;131(1):117–30. 10.1242/dev.00896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komiyama T, Sweeney LB, Schuldiner O, Garcia KC, Luo L. Graded expression of semaphorin-1a cell-autonomously directs dendritic targeting of olfactory projection neurons. Cell. 2007;128(2):399–410. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweeney LB, Chou YH, Wu Z, Joo W, Komiyama T, Potter CJ, et al. Secreted semaphorins from degenerating larval ORN axons direct adult projection neuron dendrite targeting. Neuron. 2011;72(5):734–47. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Helt JC, Wexler E, Petrova IM, Noordermeer JN, Fradkin LG, et al. Wnt5 and drl/ryk gradients pattern the Drosophila olfactory dendritic map. J Neurosci. 2014;34(45):14961–72. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2676-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jhaveri D, Sen A, Rodrigues V. Mechanisms underlying olfactory neuronal connectivity in Drosophila-the atonal lineage organizes the periphery while sensory neurons and glia pattern the olfactory lobe. Dev Biol. 2000;226(1):73–87. 10.1006/dbio.2000.9855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues V, Hummel T. Development of the Drosophila olfactory system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;628:82–101. 10.1007/978-0-387-78261-4_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fradkin LG, van Schie M, Wouda RR, de Jong A, Kamphorst JT, Radjkoemar-Bansraj M, et al. The Drosophila Wnt5 protein mediates selective axon fasciculation in the embryonic central nervous system. Dev Biol. 2004;272(2):362–75. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris KE, Beckendorf SK. Different Wnt signals act through the Frizzled and RYK receptors during Drosophila salivary gland migration. Development. 2007;134(11):2017–25. 10.1242/dev.001164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yasunaga K, Tezuka A, Ishikawa N, Dairyo Y, Togashi K, Koizumi H, et al. Adult Drosophila sensory neurons specify dendritic territories independently of dendritic contacts through the Wnt5-Drl signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 2015;29(16):1763–75. 10.1101/gad.262592.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshikawa S, McKinnon RD, Kokel M, Thomas JB. Wnt-mediated axon guidance via the Drosophila Derailed receptor. Nature. 2003;422(6932):583–8. 10.1038/nature01522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor J, Abramova N, Charlton J, Adler PN. Van Gogh: a new Drosophila tissue polarity gene. Genetics. 1998;150(1):199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolff T, Rubin GM. Strabismus, a novel gene that regulates tissue polarity and cell fate decisions in Drosophila. Development. 1998;125(6):1149–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodrich LV, Strutt D. Principles of planar polarity in animal development. Development. 2011;138(10):1877–92. 10.1242/dev.054080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Y, Mlodzik M. Wnt-Frizzled/planar cell polarity signaling: cellular orientation by facing the wind (Wnt). Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2015;31:623–46. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100814-125315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito K, Suzuki K, Estes P, Ramaswami M, Yamamoto D, Strausfeld NJ. The organization of extrinsic neurons and their implications in the functional roles of the mushroom bodies in Drosophila melanogaster Meigen. Learn Mem. 1998;5(1–2):52–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu H, Luo L. Diverse functions of N-cadherin in dendritic and axonal terminal arborization of olfactory projection neurons. Neuron. 2004;42(1):63–75. 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00142-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strutt H, Strutt D. Differential stability of flamingo protein complexes underlies the establishment of planar polarity. Curr Biol. 2008;18(20):1555–64. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinow S, White K. Characterization and spatial distribution of the ELAV protein during Drosophila melanogaster development. J Neurobiol. 1991;22(5):443–61. 10.1002/neu.480220503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ni JQ, Zhou R, Czech B, Liu LP, Holderbaum L, Yang-Zhou D, et al. A genome-scale shRNA resource for transgenic RNAi in Drosophila. Nat Methods. 2011;8(5):405–7. 10.1038/nmeth.1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ang LH, Kim J, Stepensky V, Hing H. Dock and Pak regulate olfactory axon pathfinding in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130(7):1307–16. 10.1242/dev.00356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22(3):451–61. 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu K, Sato M, Tabata T. The Wnt5/planar cell polarity pathway regulates axonal development of the Drosophila mushroom body neuron. J Neurosci. 2011;31(13):4944–54. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0154-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gratz SJ, Cummings AM, Nguyen JN, Hamm DC, Donohue LK, Harrison MM, et al. Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics. 2013;194(4):1029–35. 10.1534/genetics.113.152710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong X, Shen K, Bulow HE. Intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms of dendritic morphogenesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2015;77:271–300. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valnegri P, Puram SV, Bonni A. Regulation of dendrite morphogenesis by extrinsic cues. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38(7):439–47. 10.1016/j.tins.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman J, Anderson WJ. Experimental reorganization of the cerebellar cortex. I. Morphological effects of elimination of all microneurons with prolonged x-irradiation started at birth. J Comp Neurol. 1972;146(3):355–406. 10.1002/cne.901460305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramirez-Suarez NJ, Belalcazar HM, Salazar CJ, Beyaz B, Raja B, Nguyen KCQ, et al. Axon-Dependent Patterning and Maintenance of Somatosensory Dendritic Arbors. Dev Cell. 2019;48(2):229–44 e4. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onishi K, Shafer B, Lo C, Tissir F, Goffinet AM, Zou Y. Antagonistic functions of Dishevelleds regulate Frizzled3 endocytosis via filopodia tips in Wnt-mediated growth cone guidance. J Neurosci. 2013;33(49):19071–85. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2800-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shafer B, Onishi K, Lo C, Colakoglu G, Zou Y. Vangl2 promotes Wnt/planar cell polarity-like signaling by antagonizing Dvl1-mediated feedback inhibition in growth cone guidance. Dev Cell. 2011;20(2):177–91. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gombos R, Migh E, Antal O, Mukherjee A, Jenny A, Mihaly J. The Formin DAAM Functions as Molecular Effector of the Planar Cell Polarity Pathway during Axonal Development in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2015;35(28):10154–67. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3708-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakurai M, Aoki T, Yoshikawa S, Santschi LA, Saito H, Endo K, et al. Differentially expressed Drl and Drl-2 play opposing roles in Wnt5 signaling during Drosophila olfactory system development. J Neurosci. 2009;29(15):4972–80. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2821-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li L, Hutchins BI, Kalil K. Wnt5a induces simultaneous cortical axon outgrowth and repulsive axon guidance through distinct signaling mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2009;29(18):5873–83. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0183-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Shi J, Lu CC, Wang ZB, Lyuksyutova AI, Song XJ, et al. Ryk-mediated Wnt repulsion regulates posterior-directed growth of corticospinal tract. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(9):1151–9. 10.1038/nn1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davey CF, Mathewson AW, Moens CB. PCP Signaling between Migrating Neurons and their Planar-Polarized Neuroepithelial Environment Controls Filopodial Dynamics and Directional Migration. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(3):e1005934 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghimire SR, Ratzan EM, Deans MR. A non-autonomous function of the core PCP protein VANGL2 directs peripheral axon turning in the developing cochlea. Development. 2018;145(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grillenzoni N, Flandre A, Lasbleiz C, Dura JM. Respective roles of the DRL receptor and its ligand WNT5 in Drosophila mushroom body development. Development. 2007;134(17):3089–97. 10.1242/dev.02876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reynaud E, Lahaye LL, Boulanger A, Petrova IM, Marquilly C, Flandre A, et al. Guidance of Drosophila Mushroom Body Axons Depends upon DRL-Wnt Receptor Cleavage in the Brain Dorsomedial Lineage Precursors. Cell Rep. 2015;11(8):1293–304. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yao Y, Wu Y, Yin C, Ozawa R, Aigaki T, Wouda RR, et al. Antagonistic roles of Wnt5 and the Drl receptor in patterning the Drosophila antennal lobe. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(11):1423–32. 10.1038/nn1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmitt AM, Shi J, Wolf AM, Lu CC, King LA, Zou Y. Wnt-Ryk signalling mediates medial-lateral retinotectal topographic mapping. Nature. 2006;439(7072):31–7. 10.1038/nature04334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gierer. Directional cues for growing axons forming the retinotectal projection. Development. 1987;101:479–89. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Devenport D, Fuchs E. Planar polarization in embryonic epidermis orchestrates global asymmetric morphogenesis of hair follicles. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(11):1257–68. 10.1038/ncb1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mlodzik M. Planar polarity in the Drosophila eye: a multifaceted view of signaling specificity and cross-talk. EMBO J. 1999;18(24):6873–9. 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reifegerste R, Moses K. Genetics of epithelial polarity and pattern in the Drosophila retina. Bioessays. 1999;21(4):275–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daulat AM, Borg JP. Wnt/Planar Cell Polarity Signaling: New Opportunities for Cancer Treatment. Trends Cancer. 2017;3(2):113–25. 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Humphries AC, Mlodzik M. From instruction to output: Wnt/PCP signaling in development and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2018;51:110–6. 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu J, Mlodzik M. Wnt/PCP Instructions for Cilia in Left-Right Asymmetry. Dev Cell. 2017;40(5):423–4. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minegishi K, Hashimoto M, Ajima R, Takaoka K, Shinohara K, Ikawa Y, et al. A Wnt5 Activity Asymmetry and Intercellular Signaling via PCP Proteins Polarize Node Cells for Left-Right Symmetry Breaking. Dev Cell. 2017;40(5):439–52 e4. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu J, Roman AC, Carvajal-Gonzalez JM, Mlodzik M. Wg and Wnt4 provide long-range directional input to planar cell polarity orientation in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(9):1045–55. 10.1038/ncb2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fradkin LG, Dura JM, Noordermeer JN. Ryks: new partners for Wnts in the developing and regenerating nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33(2):84–92. 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andre P, Wang Q, Wang N, Gao B, Schilit A, Halford MM, et al. The Wnt coreceptor Ryk regulates Wnt/planar cell polarity by modulating the degradation of the core planar cell polarity component Vangl2. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(53):44518–25. 10.1074/jbc.M112.414441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Macheda ML, Sun WW, Kugathasan K, Hogan BM, Bower NI, Halford MM, et al. The Wnt receptor Ryk plays a role in mammalian planar cell polarity signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(35):29312–23. 10.1074/jbc.M112.362681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang W, Garrett L, Feng D, Elliott G, Liu X, Wang N, et al. Wnt-induced Vangl2 phosphorylation is dose-dependently required for planar cell polarity in mammalian development. Cell Res. 2017;27(12):1466–84. 10.1038/cr.2017.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dura JM, Taillebourg E, Preat T. The Drosophila learning and memory gene linotte encodes a putative receptor tyrosine kinase homologous to the human RYK gene product. FEBS Lett. 1995;370(3):250–4. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00847-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Port F, Chen HM, Lee T, Bullock SL. Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(29):E2967–76. 10.1073/pnas.1405500111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ang LH, Chen W, Yao Y, Ozawa R, Tao E, Yonekura J, et al. Lim kinase regulates the development of olfactory and neuromuscular synapses. Dev Biol. 2006;293(1):178–90. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wagh DA, Rasse TM, Asan E, Hofbauer A, Schwenkert I, Durrbeck H, et al. Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST, is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones in Drosophila. Neuron. 2006;49(6):833–44. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schematic representations of the frontal views of left ALs are shown (dorsal/0˚ is up and lateral/90˚ is to the right). A line was drawn through the centers of the DA1 and VA1d glomeruli. Where the line intersects with the dorsal-ventral axis, the angle in the clockwise direction from 0˚ was measured. During development, the DA1/VA1d angle decreases because the two glomeruli rotate around each other in the counterclockwise direction.

(TIF)

Frontal views of adult left antennae are shown (dorsal up and lateral to the right. (A-C) Representative freshly dissected antennae from animals expressing Or88a-mGFP were imaged using the confocal microscope to visualize the live Or88a neurons in the wild-type (A), Wnt5400 (B), and Mz19-Gal4 UAS-Wnt5 (C) animals. (D) Quantification of the Or88a neuronal numbers in the different genotypes. The numbers of Or88a neurons in the Wnt5400 (41.22 ± 2.681, N = 9) mutant and Mz19-Gal4 UAS-Wnt5 (32.00 ± 1.535, N = 8) overexpression animals are similar to those in the Wild type (33.17 ± 0.8776, N = 12). Wild type vs Wnt5400, p = 0.0060; Wild type vs Mz19-Gal4 UAS-Wnt5, p = 0.8834; Wnt5400 vs Mz19-Gal4 UAS-Wnt5, p = 0.0043; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.