Introduction

Understanding how physicians and nurses spend their workdays is important for improving patient care and clinician training and satisfaction. Time-in-motion studies1,2 performed by human observers have demonstrated that little time is spent engaging in direct patient care vs interacting with computers in workrooms. However, studies relying on human observation are resource intensive, introduce bias, and are costly to scale. Radiofrequency identification has been increasingly used to enable real-time location systems (RTLSs) to unobtrusively map the time and locations of health care workers.3 This cross-sectional study reports the results of an RTLS-enabled study of staff time allocation on an inpatient medicine ward.

Methods

We conducted a quality improvement project at an academic medical center to increase the amount of time spent at the bedside by physicians and nurses on 2 medicine units. This quality improvement project qualified for exemption from institutional review board review according to the institutional policy of Standard School of Medicine, and because no data were collected from patients, no informed consent was required. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.

Physician teams consisted of 1 attending physician, 1 senior resident, and 2 interns. Baseline data collection, which took place from November 1, 2017, to August 1, 2018, was enabled by radiofrequency identification trackers (Hillrom) worn by staff who opted in during their shifts and were audited by study staff twice a week. We assessed 3 location categories for which trackers detected activity, as follows: patient room, physician workroom, and hallway. A workday was defined as 7 am to 5 pm for senior residents, interns, and nurses and 9 am to 5 am for attending physicians. We included data from staff-days when more than 60% of the workday was accounted for by RTLS events. We calculated mean duration spent per location during the entire workday and during the following workday windows: prerounding (ie, 7 am to 9 am), rounding (ie, 9 am to 1 pm), and afternoon work (ie, 1 pm to 5 pm) for each clinician category (ie, intern, senior resident, attending physician, and nurse). Statistical significance was determined using a linear mixed-effects model with clinician-level random effects within each clinician category. Statistical significance was set at P < .05, and all tests were 2-tailed. All analyses were conducted in R version 3.5.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

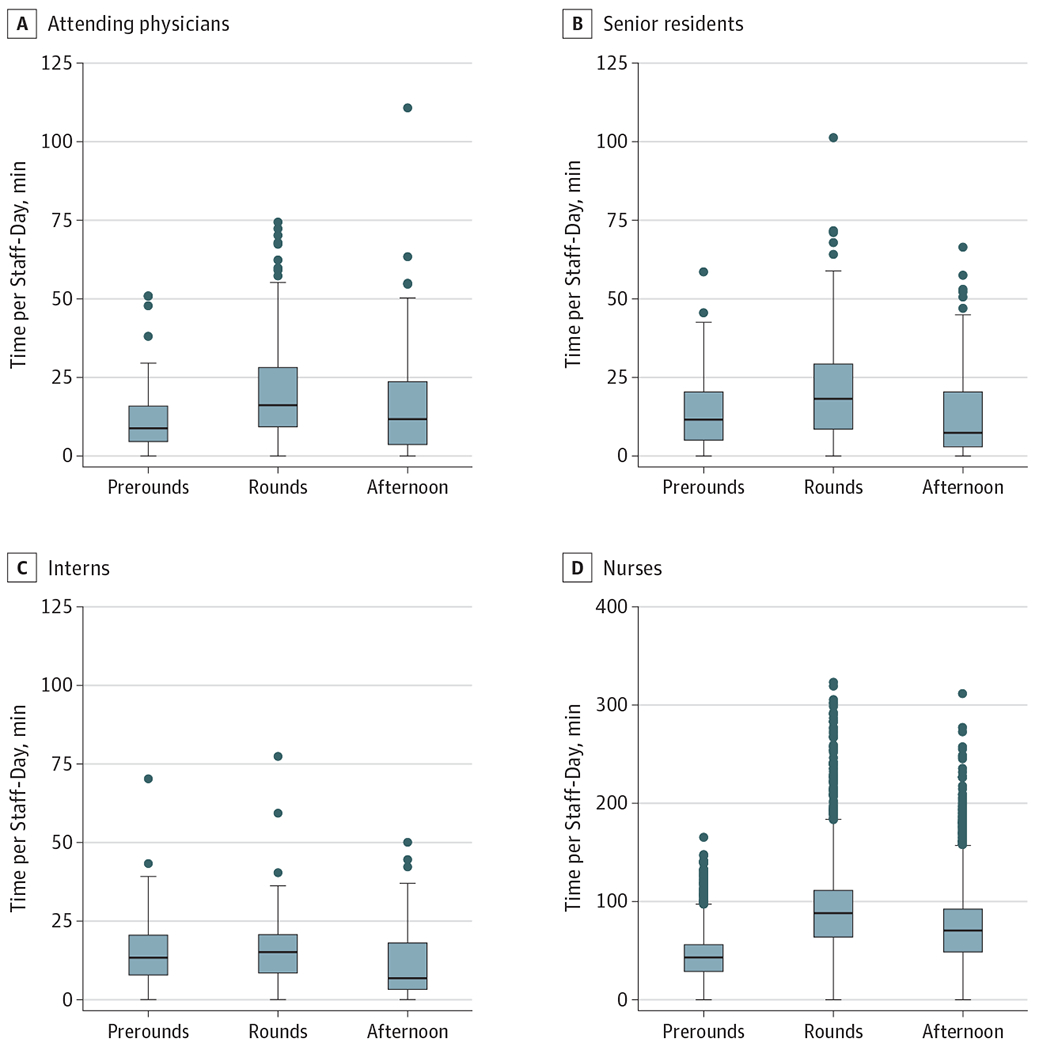

A total of 5 342 098 events were identified from 7230 of 29 278 staff-days (24.7%) included in our study. Attending physicians, senior residents, and interns spent more mean (SD) time in physician workrooms than patient rooms (attending physicians, 209.3 [97.7] minutes vs 32.9 [24.7] minutes; senior residents, 269.8 [85.0] minutes vs 39.5 [31.5] minutes; interns, 260.5 [93.2] minutes vs 35.0 [28.1] minutes), accounting for a significantly greater percentage of their workdays (attending physicians, 34.9% vs 5.5%; senior residents, 45.0% vs 6.6%; interns, 43.4% vs 5.8%; P for interaction < .001). In fact, attending physicians, senior residents, and interns spent more mean (SD) time in hallways than in patient rooms (time in hallways: attending physicians, 51.3 [29.0] minutes; senior residents, 53.8 [24.7] minutes; interns, 55.5 [30.8] minutes; P for interaction < .001). Nurses spent more than 30% of their workdays in patient rooms (mean [SD], 202.1 [75.5] minutes) (Table). Individual events in patient rooms tended to be short (mean [SD], 2.6 [3.9] minutes per event). Clinicians spent the most mean (SD) time in patient rooms during rounds (attendings, 21.2 [16.8] minutes; senior residents, 22.0 [17.9] minutes; interns, 15.6 [13.6] minutes; nurses, 89.0 [38.1] minutes; P for interaction = .001) (Figure).

Table.

Time Spent in Each Location by Staff Category per Workday and Event

| Staff Category | Mean (SD), min | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician Workroom | Patient Room | Hallway | ||||

| Duration per Workday | Duration per Event | Duration per Workday | Duration per Event | Duration per Workday | Duration per Event | |

| Attending physician | 209.3 (97.7) | 12.6 (15.6) | 32.9 (24.7) | 3.4 (5.5) | 51.3 (29.0) | 0.7 (2.0) |

| Senior resident | 269.8 (85.0) | 11.9 (17.2) | 39.5 (31.5) | 2.6 (4.4) | 53.8 (24.7) | 0.4 (1.5) |

| Intern | 260.5 (93.2) | 12.9 (17.5) | 35.0 (28.1) | 2.6 (3.8) | 55.5 (30.8) | 0.5 (1.6) |

| Nurse | 23.0 (27.8) | 1.7 (4.1) | 202.1 (75.5) | 1.9 (3.7) | 144.7 (51.4) | 0.34 (1.0) |

Figure. Time Spent in Patient Rooms by Staff Category During Each Workday Period.

The center lines of the boxes represent the median, and the upper and lower bounds indicate the third and first quartile, respectively. The upper whisker spans the third quartile to the largest value no more than 1.5 times greater than the interquartile range; the lower whisker spans the first quartile to the smallest value no less than 1.5 times less than the interquartile range. Dots indicate outlying points beyond the ranges spanned by the whiskers.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of using RTLSs to identify where clinicians spend their workdays on an inpatient medicine unit. Physicians spent little time with patients, and most events in patient rooms were shorter than 1 minute, suggesting that encounters were more often quick drop-ins than prolonged interactions. Attending physicians, senior residents, and interns spent more time in unit hallways than in patient rooms, which may reflect rounding occurring away from the patient bedside. Our study was limited by inconsistent RTLS capture of workdays among clinicians, particularly attending physicians, possibly because of variable use of the radiofrequency identification trackers. This may introduce selection bias in the included sample of clinician-days with sufficient workday capture rates.

Many residency training programs are leading efforts to increase physician engagement at the patient bedside to improve the quality of both resident education and patient care.4 Comprehensive approaches are needed to counter multiple barriers that physicians face, including frequent interruptions, increased burden from electronic health records, and noncolocated patient rooms. An audit of electronic health record use among house staff at our institution5 revealed that residents spent more than one-third of their daily shifts using electronic health records. We demonstrated that an RTLS can be a scalable method of data collection to guide improvement efforts and evaluate progress without costly human observations.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Li reported receiving consulting fees from Livongo Health and Strata Metrics outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Contributor Information

Ron C. Li, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California.

Ben J. Marafino, Biomedical Informatics Training Program, Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California.

Derek Nielsen, Stanford Health Care, Stanford, California.

Mike Baiocchi, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California.

Lisa Shieh, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chaiyachati KH, Shea JA, Asch DA, et al. Assessment of inpatient time allocation among first-year internal medicine residents using time-motion observations. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):760–767. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mamykina L, Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G. How do residents spend their shift time? a time and motion study with a particular focus on the use of computers. Acad Med. 2016;91(6):827–832. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao W, Chu CH, Li Z. Leveraging complex event processing for smart hospitals using RFID. J Netw Comput Appl. 2011;34(3):799–810. doi: 10.1016/j.jnca.2010.04.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monash B, Najafi N, Mourad M, et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):143–149. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouyang D, Chen JH, Hom J, Chi J. Internal medicine resident computer usage: an electronic audit of an inpatient service. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):252–254. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]