Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly infectious and sometimes deadly pathogen. It was first reported as an unknown form of pneumonia to the World Health Organization (WHO) at the end of December 20191. A single-stranded RNA genome consistent with a coronavirus was isolated and given the name severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which the WHO labeled COVID-19 in early February 20202. The disease has since spread globally, resulting in the ongoing pandemic, with more than a million confirmed cases worldwide. Initial reports had localized the disease to the Hubei province of China, but, by January 20, 2020, Japan, South Korea, and Thailand had reported their first cases3. The first case in the United States was identified in Washington State on January 21, 2020. On March 11, the WHO characterized the COVID-19 outbreak as a pandemic—the first since 20094. Two days later, the President of the United States declared a national state of emergency5, which reinforced the strong recommendations to curtail elective procedures as put forth by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)6, the Surgeon General, and the American College of Surgeons (ACS)7. In the following weeks, 35 states, including Washington, Colorado, Massachusetts, and New York, went further, placing moratoriums on elective procedures in order to prevent spread of the virus and to preserve the supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators7,8. The cessation of elective surgery has jeopardized the financial solvency of many health-care organizations already in distress as a result of the crisis.

The pandemic has challenged health-care organizations on many fronts, such as training medical staff on new protocols, securing scarce PPE and ventilators, and creating additional intensive care unit (ICU) and COVID-19 recovery beds, to name a few9. Without federal and state relief, the moratorium on elective procedures will further increase the financial burdens already threatening the viability of marginally resourced hospitals. Even without the pandemic, 22 health-care organizations filed for bankruptcy in 2019; this number will only increase in 202010.

Elective procedures account for 48% of hospital costs and potentially an even larger percentage of revenues9,11. Five musculoskeletal procedures (hip arthroplasty, knee arthroplasty, laminectomy, spinal fusion, and treatment of lower extremity fracture or dislocation) account for 17% of all operating room procedures in U.S. hospitals11. Without elective orthopaedic procedures, marginal health-care systems are at risk for insolvency.

The current pandemic has forced the health-care system into uncharted territory. Our health-care system relies disproportionately on elective surgical procedures as a revenue source, with these revenues being used to indirectly subsidize the care of other patients. Health care represents ≥18% of the gross domestic product, and the loss of 3 months of elective surgery will lead to an annual decrease of hospital revenue of approximately 12.5%12. Hospital profit margins on average are not able to overcome these losses. This will cause financial constraints for hospitals and surgeons, leading to budget cuts and employee furloughs. Given the size of the health-care sector, this contraction will greatly contribute to growing unemployment and recession in the overall national economy.

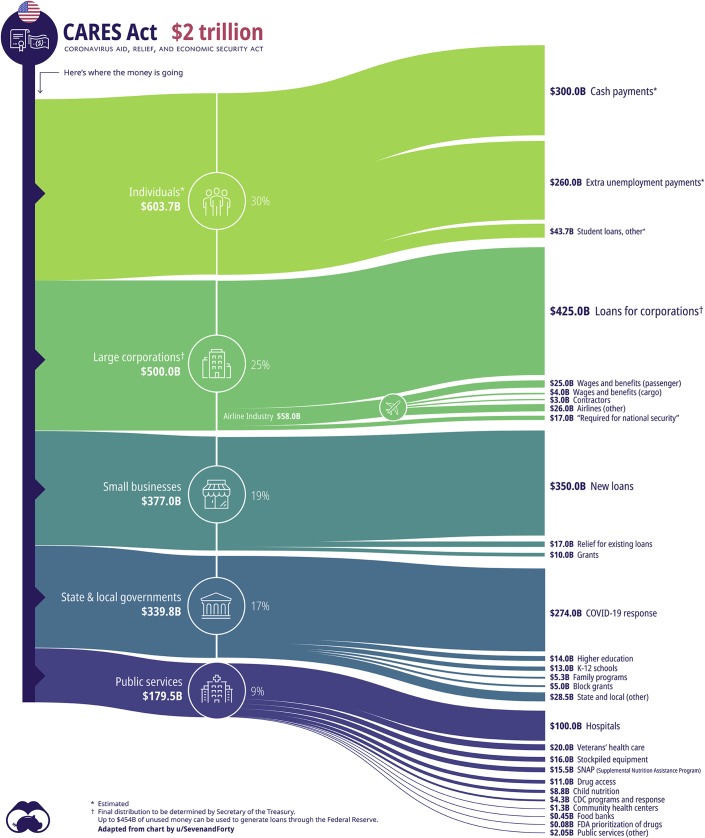

In response to the crisis, the federal government passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, a $2 trillion relief fund strategically aiding individuals, businesses, and state and local governments, while maintaining public services13 (Fig. 1). Aside from the centerpiece deployment of “helicopter money”—a $1,200 direct payment to individuals and families—the bill designates $100 billion to hospitals and raises Medicare reimbursements by 20% for care rendered to COVID patients. Although it is still unclear how the $100 billion will be allotted (e.g., demand versus caseload, rural versus urban, academic versus community organizations), the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) has been empowered to quickly oversee its distribution, providing hospitals with funding for expenses relating to constructing temporary structures and obtaining medical supplies (e.g., ventilators, PPE). In the absence of more specific guidelines, the funding will potentially disproportionately benefit larger health-care organizations14.

Fig. 1.

Illustration showing the distribution of funds according to the CARES Act. (Reproduced, with permission, from: Routley N. The anatomy of the $2 trillion COVID-19 stimulus bill. Visual Capitalist. 30 Mar 2020. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/the-anatomy-of-the-2-trillion-covid-19-stimulus-bill/.)

Health-care systems are not solely affected. Orthopaedic practices spend >$33,000 per month per surgeon to maintain overhead for their offices15. Orthopaedic private practices face additional costs for maintaining ambulatory surgical centers and high medical malpractice costs, while reduced reimbursement rates have increased the capital expenditures needed to run a successful practice. As a result, orthopaedic practices have become reliant on elective procedures, exposing them to increased financial risk. The COVID-19 crisis has resulted in the rapid cancellation of elective procedures, replacing revenue with liabilities as seen in the hypothetical example shown in Table I. The moratorium on elective procedures, combined with the high overhead costs of maintaining a private orthopaedic practice, has placed orthopaedic groups in a difficult position. New England Orthopedic Surgeons, based in Springfield, Massachusetts, has had to withhold all surgeon pay and furlough 168 employees16. Similarly, the Rothman Institute, in Philadelphia, has made the decision to retain employees in lieu of paying its surgeons17. Many other orthopaedic groups are facing the same challenges. Emergency funding from the government loan programs offers potential aid for private orthopaedic practices during this crisis.

TABLE I.

Microeconomic Effect on an Orthopaedic Surgery Practice Associated with Unanticipated Reduction in Projected Revenue in the Setting of Fixed Overhead Costs*

| Scenario | Actual Revenue | Fixed Overhead | Gross Profit | Change in Gross Profit† |

| No crisis | $1,000,000 | $600,000 | $400,000 | NA |

| Crisis | $750,000 | $600,000 | $150,000 | −62.5% |

Assumptions: (1) $1 million projected revenue per physician per year, (2) fixed overhead is 60% of projected revenue, (3) crisis reduces actual revenue by 25%.

NA = not applicable.

The CARES Act has designated an additional $350 billion in new loans to small businesses, which include private orthopaedic practices13. The United States Small Business Administration (SBA) now has several programs available for businesses with ≤500 employees (Table II)18. The program most applicable to private orthopaedic practices is the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which provides a maximum of $10 million or 2.5 times the average monthly payroll in 2019 (whichever is less). In addition, regulators have reduced all SBA-levied fees, the maximum interest rate is locked at 1%, and a guarantor is no longer needed. These loans are eligible for full or partial forgiveness if used to fund (1) payroll, (2) utilities, (3) rent, (4) mortgage, and/or (5) existing business debt. To maintain eligibility for forgiveness, businesses must not terminate contracts with current employees or must rehire employees and maintain employment until the end of June. If the number of employees is reduced during the first 8 weeks after loan distribution, the amount of forgiveness will decrease, and, if the employees who were laid off made <$100,000 per year, the amount of forgiveness may further decrease. Notably, the PPP can be combined with other SBA programs, including the Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program; however, these programs have funding caps and are being dispensed on a rolling basis. Unfortunately, given the high capital expenditure inherent to orthopaedic surgery practices, the PPP and EIDL loans will not be sufficient for the largest groups. It is still unclear which loan programs these large groups will qualify for.

TABLE II.

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act-Funded Programs Managed by the United States Small Business Administration (SBA)18

| Program | Amount* | Stipulations |

| Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) | Up to $10 million |

|

| SBA Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) and Loan Advance | Loan advance: $10,000Loan: up to $2 million |

|

| SBA Express Bridge Loans | Up to $25,000 |

|

| SBA Debt Relief Program | NA |

|

| SBA Express Loan | Up to $1 million |

|

NA = not applicable.

We are in the midst of a health-care crisis that presents unique challenges for all Americans. During times of hardship, it is important that all health-care professionals, regardless of their training, come together and do what is best for their patients, families, and colleagues. Orthopaedic surgeons have done their part in drastically reducing non-urgent surgical case volumes with the goal of minimizing exposure and preserving PPEs. We recommend a continued reduction in all nonessential procedures as we move through the most critical period. In addition, we strongly recommend that all private orthopaedic practices review the SBA PPP guidelines and how they best apply to their groups. The programs and relief funds that have been instituted should ease the economic burden; however, it is imperative that orthopaedic surgeons take an active role. Last, clear communication among orthopaedic practices, health-care organizations, and both state and national orthopaedic societies (e.g., New York State Society of Orthopaedic Surgeons [NYSSOS]19, Massachusetts Orthopaedic Association [MOA]20, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons [AAOS]21) helps to enhance our response.

When the time comes that we are emerging from the peak in COVID-19 cases, great care will need to be taken when returning to elective surgical cases in order to ensure the safety of surgical staff, patients, and the care team. The availability of accurate, timely testing for all who are involved in surgical care will be necessary. The continued availability of ventilators, beds, blood supplies, medications, and appropriate PPE for the surgical and care teams will be necessary. A second outbreak in the autumn in North America remains a threat. Reliable antibody tests demonstrating immunity would go a long way toward accelerating our ability to go back to a more normal health-care reality. National guidelines for returning to normal elective surgical schedules will help to ensure a smooth, safe transition.

Acknowledgments

Note: The authors thank Nick Routley and Visual Capitalist for permitting us to use their image.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Albany Medical Center, Albany, New York, and the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Disclosure: The authors indicated that no external funding was received for any aspect of this work. The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJS/F862).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). 2020. Accessed 2020 Apr 7 https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. 2020. Accessed 2020 Apr 7 https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report - 1. 21 January 2020. 2020. Accessed 2020 Apr 7 https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=20a99c10_4 [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. 2020. Accessed 2020 Apr 8 https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trump DJ. Proclamation on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. 2020. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/ Accessed 2020 Apr 7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Non-emergent, elective medical services, and treatment recommendations. 2020. Accessed 2020 Apr 7 https://www.cms.gov/files/document/31820-cms-adult-elective-surgery-and-procedures-recommendations.pdf

- 7.Setting PIS, Phase P. COVID-19: guidance for triage of non-emergent surgical procedures. American College of Surgeons; 2020 Mar 17. https://www.facs.org/about-acs/covid-19/information-for-surgeons/triage Accessed 2020 Apr 7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambulatory Surgery Center Association. State guidance on elective surgeries. 2020. Accessed 2020 Apr 8 https://www.ascassociation.org/asca/resourcecenter/latestnewsresourcecenter/covid-19/covid-19-state [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicholson S, Ash DA. Hospitals need cash. Health insurers have it. 2020. Mar 25, https://hbr.org/2020/03/hospitals-need-cash-health-insurers-have-it Accessed 2020 Apr 7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellison A. 22 hospital bankruptcies in 2019. Becker’s hospital CFO report. 2020. January 6 Accessed 2020 Feb 4 https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/22-hospital-bankruptcies-in-2019.html [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCPUnet. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Accessed 2020 Apr 7 http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov [Google Scholar]

- 12.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditure data. 2019. Accessed 2020 Mar 4 https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical

- 13.116th Congress. S.3548 - CARES Act. 2020. Accessed 2020 Apr 7 https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3548/text

- 14.Schwartz K, Neuman T. A look at the $100 billion for hospitals in the CARES Act. 2020. Mar 31, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-policy-watch/a-look-at-the-100-billion-for-hospitals-in-the-cares-act/ Accessed 2020 Apr 7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sathiyakumar V, Jahangir AA, Mir HR, Obremskey WT, Lee YM, Thakore RV, Sethi MK. Patterns of costs and spending among orthopedic surgeons across the United States: a national survey. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2014. January;43(1):E7-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn AG. Coronavirus: New England Orthopedic Surgeons furloughs half its workforce. 2020. Mar 23, https://www.masslive.com/coronavirus/2020/03/coronavirus-new-england-orthopedic-surgeons-furloughs-half-its-workforce.html Accessed 2020 Apr 7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyrda L. Rothman surgeons drop pay to avoid employee layoffs, shift to telemedicine: 4 details. 2020. Mar 25, https://www.beckersspine.com/orthopedic-spine-practices-improving-profits/item/48654-rothman-surgeons-drop-pay-to-avoid-employee-layoffs-shifts-to-telemedicine-4-details.html Accessed 2020 Apr 7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Small US. Business Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19): small business guidance & loan resources. 2020. Accessed 2020 Apr 7 https://www.sba.gov/page/coronavirus-covid-19-small-business-guidance-loan-resources [Google Scholar]

- 19.NYS Society of Orthopaedic Surgeons. COVID-19 legislative packages: small business relief. 2020. Accessed 2020 Mar 4 https://nyssos.org/cov19nyorthopod [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massachusetts Orthopaedic Association. COVID-19 information & updates for the orthopaedic community. 2020. Accessed 2020 Mar 4 https://www.massortho.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. COVID-19: member resource center. 2020. Accessed 2020 Mar 4 https://www.aaos.org/about/covid-19-information-for-our-members/ [Google Scholar]