Abstract

Using longitudinal data spanning a seven year period we investigated the behavioral and psycho-social effects resulting from a parent’s death during adolescence and early adulthood. Findings confirmed previous work demonstrating various behavioral problems and social-psychological adjustment deficits during adolescence. Results suggested that most detrimental adjustment behaviors among parentally bereaved youth fade as they entered into young adulthood. Yet, premature school withdrawals and diminished interests in college attendance at Wave 1 left many of these young adults with diminished academic accomplishments, lingering economic disadvantages and a hesitancy to marry as their lives progressed into adulthood.

Keywords: parental death, adolescents, early adulthood, longitudinal study

Introduction

It has been claimed that close to 4% of American children, representing over 3,000,000 children from current US Census estimates, will experience the death or one or both parents before reaching the age of 18 (Social Security Administration, 2000). These large numbers of bereaved children have been the subject of much previous research. Though there have been no review articles completed recently, at least three such articles summarized the vast array of findings on the detrimental effects to adolescents from early parental death (Osterweis, Solomon & Green, 1984; Tennant, Bebbington & Hurry, 1980; Dowdney, 2000).

Past studies have found parentally bereaved adolescents at greater risk for a wide array of adjustment problems compared to their non-bereaved counterparts. They have been found to have a greater risk of premature death (Li, Verergaard, Cnattingius, Gissler, Hammer Bech, Obel, & Olsen, 2014), suicide attempts (Jakobsen & Christiansen, 2011), to experience depression (Jacobs & Bovasso, 2009; Yagla Mack, 2001), to have more severe and greater numbers of other psychiatric difficulties, (Dowdney, 2000), to have lower grades and more school failures (Berg, Rostila, Saarela & Hjern, 2014), lower self-esteem (Worden & Silverman, 1996), greater involvement in youth delinquency,(Draper & Hancock, 2011), more drug abuse (von Sydow, Lieb, Pfister, Höfler, & Wittchen, 2002) and more violent crime involvements (Wilcox, Satoko, Kuramoto, Lichtenstein, Långström, Brent, & Runeson, 2010).

Most studies of the effects of parental loss have focused primarily upon adolescent populations, often obtaining consistent associations with the above mentioned correlates and parental death. Since young adults in their mid-twenties have seldom been the focus of the parental loss bereavement studies, one may wonder whether the findings that have been obtained for adolescents will apply to young adults.

Several previous researchers have suggested that with time after a loss, a parent’s death may recede from being a primary cause of depression and other psychiatric difficulties. At least three studies have suggested this. Tennant, et al.’s (1980) review article claims, “When experimental and control samples were most rigorously matched, no association was found between childhood parental bereavement and depression in later life. Parental death in childhood appears to have little effect on adult depressive morbidity.” A more recent Dutch epidemiological study, (Stickelbroek, Prinzie, de Graaf, Ten Have, & Cuijpers, 2012), based on a study of health records of over 7,000 patients, found “few indications that there was a significant increase in mental disorders in adulthood among people who lost a parent before the age of 16 (N=541)….The majority of children overcome the loss of a parent during childhood without experiencing increased mental health problems, reduced functional limitations or a greater need for mental health services during adulthood.” Cerel, Fristad, Verducci, & Weller’s (2006) findings are also convergent with these results. They completed a longitudinal study of three demographically matched groups consisting of parentally bereaved youth, depressed controls and community controls. Initially, they found depressed controls stood out with the highest levels of psychiatric dysfunctionality, with parentally bereaved youth somewhat below them in psychiatric difficulties at the outset of their study. Two years later, the parentally bereaved had measurements of psychiatric impairment that more nearly approximated the responses of the community controls, at the lowest levels of psychiatric dysfunctionality, while depressed controls still remained at the highest end of psychiatric dysfunctionality.

Thus, these three studies, despite their diverging methodologies, all suggest that time after a loss is an important factor in altering parental bereavement adaptations and ameliorating psychic distress associated with early parental death. Results also suggest that parentally bereaved adolescents are most likely to exhibit various psycho-social problems that have been mentioned above. Young adults, by contrast, with a longer time since their childhood losses, may exhibit fewer of these psycho-social adjustment difficulties. We sought to examine these hypotheses with data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health.

Method

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, (widely known as the Add Health Survey), began in 1995 with a nationally representative sample of more than 20,000 high school students, who were first interviewed in 1995. Students from 80 selected high schools, representing the national high school population, were chosen to participate in a comprehensive survey of their life styles, school experiences, health-related behaviors, drug use and criminal conduct, mental health status, friendships, dating and sex behaviors. At the time of the Wave 1 survey, 20,745 students, ranging in age mostly from 13 to 19, were interviewed at their homes.

Wave 2 took place one year later with over 15,000 respondents participating. Six years later another follow-up, Wave 3 survey was conducted, with 15,197 respondents, at ages ranging from 18 to 26, answering another exhaustive array of questions about their health and behavior patterns. Seventy-three percent of Wave 1 respondents participated at Wave 3. At Wave 3, slightly over 2/5s of all respondents, or 44%, were still in school full-time, mostly attending colleges. Our analysis contrasted the responses of survey participants at Wave 1 and Wave 3.

It should also be noted that Add Health also included surveys from over 17,000 parents and guardians collected at Wave 1. A Wave 4 survey was also conducted in 2007 and 2008 with over 15,000 respondents participating, exhibiting an 80% response rate compared to the previous survey. In 2014 Add Health released cause of death data on 227 survey respondents who died between four and twelve years after completing their Wave 1 surveys.

At Wave 1 all adolescent respondents were asked to provide a household roster and to identify their relationship to other household members. If a biological mother was not named as a household member participants were asked if their biological mother was still living. 330 respondents indicated their biological mother was deceased. A similar format was used to ascertain the presence or absence of a respondent’s biological father; 788 indicated that their biological fathers were deceased. Of these 1,118 cases of respondents sustaining the death of a parent, we subtracted out 28 cases who indicated growing up in two-parent adoptive families. Thus at Wave 1, 8,626 indicated they lived with both biological parents, 760 experienced the loss of their father, 302 the loss of their mother, 28 reported both parents deceased and 11,059 remaining cases reported living either with one parent, step-parents, adoptive parents, or with other relatives at that time. Our analyses compared and contrasted the children reporting the death of one or both parents (N=1,090) compared to those living in intact biological parent homes (N=8,626). Consistent with much previous research on parental death we did separate analyses for males and females.

We contrasted Wave 1 respondents on a wide variety of behavioral indicators: health status, whether they engaged in delinquent conduct or fighting, had experiences of depression, suicide thoughts and attempts, used drugs and alcohol, school suspensions and expulsions, used mental health and drug treatment services.

Measures

Depression.

Symptoms of depression were assessed via a 19-item variation of the CES-D scale (Radloff, 1977) at Wave 1, assessing depression experienced during the past 12 months. Responses ranged from 0 (Rarely or none of the time) to 3 (Most or all of the time), with higher total scores indicating more prevalent depressive symptoms. Sample items included: “felt you could not shake off the blues,” “felt depressed,” etc. Alpha coefficient was .86. At Wave 3 only 9 of the original 19 items were presented to survey respondents.

Self-esteem.

A self-esteem scale was created from nine items, offered at Wave 1, on a five-point Likert type scale. Sample items include, “You have a lot of good qualities” and “You have a lot to be proud of. Alpha coefficient was .86. At Wave 3 only 4 of the original 9 items were presented to survey respondents.

Delinquency.

At Wave 1 and Wave 3 all respondents were given a list of 15 different delinquent acts and asked whether they had engaged in any and if so, how frequently in the past 12 months. The list included such behaviors as painting graffiti, deliberately damaging property, stealing things, getting into a physical fight, going into a house to steal things, selling illegal drugs, taking a car without its owner’s permission, etc. Alpha coefficient was .83.

Violence.

We created a nine-item scale of fighting and violent actions at Wave 1 and Wave 3. Respondents were asked if, in the last 12 months, they had witnessed someone shoot or stab someone else; if someone had pulled a knife or gun on them; if someone had shot or knifed them; if they were jumped; if they had shot or knifed someone else and if they had been seriously injured in a fight that required medical care. Alpha coefficient was .72.

Material Advantages Index.

At Wave 3 respondents provided information on whether they owned their residences, owned a car, computer, had an email account, had savings and checking accounts and had a credit card. From these seven questions we created an eight-point scale of material advantages, yielding an alpha coefficient of .66.

Dispossessed

At Wave 3 respondents were asked if in the past 12 months they were ever without telephone service, did not pay the full amount of their rent or mortgage, were ever evicted from their residence, did not pay the full amount of their utility bill, had their utility services cut off, or did not go to see a doctor or dentist because they were unable to pay for their services. These seven items were moderately inter-correlated and produced an alpha coefficient of .67.

Wave 3 also included a number of new questions about a respondent’s living arrangements not asked at Wave 1, when the overwhelming majority were in high school, living with parents. Many questions were also repeated at Wave 3: drug and alcohol use, suicide thoughts and attempts, use of mental health and drug treatment services.

Results

As Table 1 shows both males and females exhibit significantly greater delinquency and fighting behavior when experiencing the death of a parent, compared to those living in intact biological parent families. The parentally bereaved also displayed a greater tendency to run away from home at Wave 1, with nearly double the risk for both males and females, as compared to those in intact biological parent families.

Table 1:

Comparison of Behaviors of Male and Female Children in Intact Households versus Households with One or More Deceased Parents

| Characteristic (Wave 1) | Males | Females | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value | |

| Think about suicide past year | ||||||||

| Yes | 9.0 | 14.3 | 14.2 | 0.0001 | 14.2 | 17.3 | 3.9 | 0.05 |

| No | 91.0 | 85.7 | 85.8 | 82.7 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,266 | 497 | 4,274 | 584 | ||||

| Suicide Attempts past year | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.8 | 4.4 | 14.6 | 0.001 | 4.2 | 7.3 | 11.7 | 0.001 |

| No | 98.2 | 95.6 | 95.8 | 92.7 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,310 | 502 | 4,313 | 588 | ||||

| Days Smoked in Past 30 Days | ||||||||

| None | 74.9 | 76.2 | 1.8 | 0.61 | 78.2 | 74.5 | 19.9 | 0.0001 |

| 5 or Less | 9.3 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 8.0 | ||||

| 6–29 Days | 8.0 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 6.7 | ||||

| Daily | 7.8 | 8.7 | 6.0 | 10.8 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,279 | 496 | 4,291 | 584 | ||||

| Got Drunk Past year | ||||||||

| One time a Week | 6.0 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 0.008 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 6.8 | 0.03 |

| Monthly or Less | 21.5 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 23.0 | ||||

| Never | 72.5 | 69.3 | 76.1 | 72.7 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,303 | 501 | 4,308 | 587 | ||||

| Times Smoked Pot Past 30 Days | ||||||||

| Never | 87.0 | 82.1 | 12.9 | 0.002 | 89.9 | 83.9 | 18.9 | 0.0001 |

| 1–10 Times | 9.1 | 10.9 | 8.3 | 13.0 | ||||

| >10 Times | 3.9 | 7.0 | 1.8 | 3.1 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,234 | 486 | 4,259 | 579 | ||||

| Used Cocaine | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.8 | 4.1 | 2.7 | 0.09 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 15.9 | 0.0001 |

| No | 97.2 | 95.9 | 98.4 | 96.0 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,245 | 486 | 4,268 | 583 | ||||

| Used Inhalants | ||||||||

| Yes | 6.3 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 0.07 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 1.7 | 0.2 |

| No | 93.7 | 95.8 | 95.1 | 93.9 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,247 | 482 | 4,265 | 586 | ||||

| Used Other Illegal Drugs | ||||||||

| Yes | 6.9 | 7.9 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 5.9 | 7.6 | 2.5 | 0.1 |

| No | 93.1 | 92.1 | 94.1 | 92.4 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,238 | 482 | 4,258 | 578 | ||||

| Ever Injected Drugs | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.4 | 1.6 | 12.7 | 0.0001 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 6.4 | 0.01 |

| No | 99.6 | 98.4 | 99.8 | 99.1 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,272 | 494 | 4,280 | 588 | ||||

| Ever Repeat a Grade in School | ||||||||

| Yes | 20.4 | 33.2 | 43.4 | 0.0001 | 12.2 | 22.5 | 46.3 | 0.0001 |

| No | 79.6 | 66.8 | 87.8 | 77.5 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,305 | 500 | 4,307 | 588 | ||||

| Suspended from School | ||||||||

| Yes | 27.3 | 46.4 | 79.2 | 0.0001 | 12.5 | 33.2 | 172 | 0.0001 |

| No | 72.7 | 53.6 | 87.5 | 66.8 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,303 | 502 | 4,306 | 588 | ||||

| Expelled from School | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.7 | 7.8 | 19.0 | 0.0001 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 62.7 | 0.0001 |

| No | 96.3 | 92.2 | 98.6 | 93.7 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,302 | 498 | 4,305 | 588 | ||||

| Received Counseling | ||||||||

| Yes | 7.0 | 13.6 | 27.4 | 0.0001 | 9.6 | 19.6 | 52.7 | 0.0001 |

| No | 93.0 | 86.4 | 90.4 | 80.4 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,302 | 501 | 4,306 | 588 | ||||

| Substance Abuse Program | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.4 | 4.6 | 8.2 | 0.004 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 4.5 | 0.03 |

| No | 97.6 | 95.4 | 98.3 | 97.1 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,305 | 502 | 4,304 | 588 | ||||

| Times Run Away from Home | ||||||||

| Never | 94.9 | 91.2 | 15.4 | 0.0001 | 93.3 | 87.2 | 43.5 | 0.0001 |

| 1–2 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 5.7 | 8.7 | ||||

| 3+ | 0.8 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 4.1 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,276 | 498 | 4,286 | 588 | ||||

| Males | Females | |||||||

| Characteristic (Wave 1) | Mean Intact Household (SD) | Mean One or More Deceased Parents (SD) | F-test | p-value | Mean Intact Household (SD) | Mean One or More Deceased Parents (SD) | F-test | p-value |

| Delinquency Score | 3.03 (2.9) | 3.44 (3.1) | 8.7 | 0.003 | 2.19 (2.3) | 2.67 (2.7) | 21.3 | 0.0001 |

| Total Sample Size | 4,242 | 494 | 4,269 | 580 | ||||

| Fighting & Violence | 1.05 (1.5) | 1.51 (1.8) | 39.6 | 0.0001 | 0.41 (0.9) | 0.74 (1.2) | 58.5 | 0.0001 |

| Total Sample Size | 4,238 | 489 | 4,269 | 583 | ||||

| CES-D Depression | 9.56 (6.4) | 11.37 (7.3) | 34.8 | 0.0001 | 11.11 (7.6) | 13.95 (9.2) | 67.9 | 0.0001 |

| Total Sample Size | 4,286 | 496 | 4,290 | 585 | ||||

| Self Esteem | 16.09 (4.7) | 16.56 (4.8) | 4.5 | 0.03 | 17.82 (5.1) | 18.36 (5.0) | 5.5 | 0.02 |

| Total Sample Size | 4,285 | 493 | 4,283 | 581 | ||||

| General Health | 2.00 (0.9) | 2.11 (0.9) | 7.7 | 0.006 | 2.12 (0.9) | 2.30 (0.9) | 18.4 | 0.0001 |

| Total Sample Size | 4,308 | 501 | 4,307 | 588 | ||||

| Want to Attend College | 4.39 (1.1) | 4.18 (1.2) | 16.0 | 0.0001 | 4.59 (0.9) | 4.40 (1.0) | 21.6 | 0.0001 |

| Total Sample Size | 4,285 | 498 | 4,287 | 582 | ||||

| Getting along w/teachers | .9 (.9) | 1.01 (1.0) | 6.6 | 0.01 | .7 (0.9) | .8 (1.0) | 8.5 | 0.004 |

| Total Sample Size | 4,252 | 490 | 4,243 | 569 | ||||

Table 1 also shows greater amounts of self-reported drug use for the parentally bereaved adolescents compared to their non-bereaved peers. While bereaved males were no more likely to smoke cigarettes than their non-bereaved male peers, bereaved girls were more likely to smoke compared to their non-bereaved peers. Both the males and the females who were bereaved reported higher levels of alcohol use, and a greater likelihood of to smoke marijuana and/or to use injected drugs. This finding did not extend to the use of other drugs, including cocaine and inhalants.

Table 1 also shows both genders of parentally bereaved adolescents as more likely to have been suspended or expelled from schools, to have repeated a grade, as more likely to feel that teachers did not care about them and less hopeful about ever going to college. The table also shows parentally bereaved boys and girls express more depressive symptoms, possess diminished self-esteem, have more suicidal thoughts and attempts and view their overall health less favorably, as compared to non-bereaved controls. The parentally bereaved were also more likely to have sought mental health counseling and drug rehabilitation services compared to their non-bereaved peers.

All these associations with parental bereavement have been found in other studies, correlated with social class and racial minority status. Even parental bereavement itself has been associated with social class and minority membership. In our data we noted that the experience of parental death was two to five times more common among lower SES families as compared to those in economically advantaged homes and twice as common among adolescents who were racial minority members. To control for these potential confounders we re-examined each of the significant associations found for Wave 1 observations using OLS (Ordinary least squares) with each correlate as the dependent variable and parental bereavement status (death of at least one parent vs. no death), social class (divided into four diverging income categories) and minority status (white vs. all non-whites) as control variables. The results showed that only one association no longer remaining significantly associated with parental bereavement after adjustment: self esteem. Thus, it appears that self-esteem differences are heavily interwoven with social class and racial minority status, nullifying the direct bivariate association between self-esteem and parental bereavement.

Table 2 compares and contrasts the delinquency and criminal involvements of respondents at Wave 3 when they were between the ages of 18 and 26. It shows no differences in delinquent participation between young adults, who previously reported a parent’s death, compared to their non-bereaved peers. Further, bereaved males matched non-bereaved males in exposure to violence and fighting, but bereaved females did show significantly higher exposures to fighting than their non-bereaved counterparts. Wave 3 asked respondents numerous questions about whether they were ever arrested, were convicted or pled guilty to crimes, or had spent any time in probation or at correctional facilities. No differences were found on these characteristics among the bereaved (and the non-bereaved) within each gender subgroup.

Table 2:

Wave 3 Comparison of Characteristics of Male and Female Children in Intact Households versus Households with One or More Deceased Parents

| Characteristic | Males | Females | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value | |

| Living Arrangements | ||||||||

| Where respondent Lives now | ||||||||

| With Parents | 48.1 | 34.5 | 33.8 | 0.0001 | 42.1 | 29.7 | 40.6 | 0.0001 |

| With Others | 4.2 | 9.0 | 3.8 | 7.6 | ||||

| Has Own Place | 41.3 | 51.3 | 47.7 | 58.7 | ||||

| Group Home | 6.0 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 3.3 | ||||

| Homeless | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | ||||

| Other | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,249 | 310 | 3,555 | 421 | ||||

| Respondent Lives with Others | ||||||||

| Alone | 7.5 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 0.001 | 7.6 | 9.1 | 5.4 | 0.069 |

| With Others | 86.4 | 82.3 | 86.5 | 87.6 | ||||

| Group Home | 6.1 | 4.5 | 5.9 | 3.3 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,250 | 310 | 3,555 | 419 | ||||

| Ever Stayed in a Homeless Shelter | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.703 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 10.3 | 0.001 |

| No | 99.2 | 99.0 | 99.1 | 97.4 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,246 | 309 | 3,554 | 421 | ||||

| Parents Ordered Resp. to Move Out | ||||||||

| Yes | 7.6 | 12.6 | 9.6 | 0.002 | 6.0 | 12.1 | 22.7 | 0.0001 |

| No | 92.4 | 87.4 | 94.0 | 87.9 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,246 | 310 | 3,550 | 421 | ||||

| Ever Lived in a Treatment Home | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.2 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 0.035 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 23.8 | 0.0001 |

| No | 98.8 | 97.4 | 99.1 | 96.4 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,249 | 309 | 3,553 | 421 | ||||

| Males | Females | |||||||

| Characteristic (Wave 3) | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value |

| Crime and Drug Use | ||||||||

| Ever arrested | ||||||||

| Yes | 16.2 | 19.3 | 2.0 | 0.157 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 0.310 |

| No | 83.8 | 80.7 | 96.4 | 95.4 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,223 | 305 | 3,540 | 418 | ||||

| Times Arrested before age 18 | ||||||||

| None | 94.1 | 92.2 | 2.02 | 0.363 | 99.0 | 98.8 | .10 | 0.958 |

| One | 3.2 | 3.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | ||||

| Two or more | 2.7 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,245 | 309 | 3,554 | 421 | ||||

| Ever Convicted/ Pled Guilty | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.4 | 3.6 | 1.65 | 0.199 | 0.3 | 0.2 | .11 | 0.73 |

| No | 97.6 | 96.4 | 99.7 | 99.8 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,246 | 309 | 3,554 | 421 | ||||

| Days Smoked Cigarettes Past Month | ||||||||

| Not Smoking | 66.8 | 72.1 | 4.45 | 0.217 | 73.3 | 72.8 | 5.27 | 0.153 |

| 1 – 14 Days | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 4.5 | ||||

| 15 – 29 Days | 6.5 | 4.2 | 5.3 | 3.3 | ||||

| Daily | 21.5 | 18.8 | 16.2 | 19.3 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,243 | 308 | 3,549 | 419 | ||||

| Total Used of 8 Illegal Drugs | ||||||||

| None | 64.9 | 68.1 | 1.86 | 0.761 | 71.2 | 74.4 | 3.85 | 0.427 |

| One | 15.4 | 15.1 | 15.4 | 14.3 | ||||

| Two | 6.1 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 4.2 | ||||

| Three | 4.0 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 3.4 | ||||

| Four or More | 9.6 | 7.7 | 5.4 | 3.7 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,164 | 298 | 3,498 | 406 | ||||

| Males | Females | |||||||

| Characteristic | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value |

| Number of Cigarettes Smoked Per Day | ||||||||

| Not Smoking | 66.3 | 71.8 | 4.41 | 0.353 | 73.1 | 72.3 | 8.49 | 0.075 |

| < 10 Cigarettes | 18.1 | 16.2 | 18.7 | 17.2 | ||||

| < Pack | 5.5 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.8 | ||||

| Pack Daily | 7.4 | 6.2 | 7.4 | 4.3 | ||||

| > Pack Daily | 2.7 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 2.4 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,232 | 308 | 3,549 | 419 | ||||

| Days Binge Drinking Past Year | ||||||||

| None | 40.8 | 54.6 | 23.1 | 0.0001 | 56.8 | 68.7 | 27.8 | 0.0001 |

| < Monthly | 25.9 | 22.1 | 28.9 | 22.9 | ||||

| Weekly | 27.1 | 18.5 | 12.7 | 6.2 | ||||

| > Weekly | 6.2 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 2.2 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,237 | 308 | 3,541 | 419 | ||||

| Days Been Drunk Past Year | ||||||||

| None | 41.5 | 52.4 | 15.7 | 0.0001 | 51.1 | 64.0 | 29.2 | 0.001 |

| < Monthly | 30.6 | 27.8 | 35.1 | 28.4 | ||||

| Weekly | 24.0 | 16.8 | 12.7 | 6.4 | ||||

| > Weekly | 3.9 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,234 | 309 | 3,541 | 419 | ||||

| Days Used Marijuana Past Month | ||||||||

| None | 75.0 | 77.3 | 4.00 | 0.135 | 83.8 | 86.4 | 3.09 | 0.213 |

| < 10 | 13.6 | 9.7 | 11.4 | 8.6 | ||||

| 30 or > | 11.4 | 13.0 | 4.7 | 5.0 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,237 | 308 | 3,548 | 419 | ||||

| Taken Stimulants | ||||||||

| Yes | 9.2 | 7.9 | 0.55 | 0.458 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 0.46 | 0.497 |

| No | 90.8 | 92.1 | 94.3 | 95.1 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,205 | 304 | 3,522 | 409 | ||||

| Males | Females | |||||||

| Characteristic (Wave 3) | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value |

| W3 Mental and psychological health status | ||||||||

| Saw MH counselor past yr., Wave 3 | ||||||||

| Yes | 4.6 | 4.8 | .03 | .859 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 1.41 | .236 |

| No | 95.4 | 95.2 | 91.1 | 92.9 | ||||

| Total sample size | 3,249 | 310 | 3,550 | 421 | ||||

| Drug rehab past yr., Wave 3 | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.0 | 5.5 | 5.88 | .015 | 1.1 | 0.7 | .67 | .414 |

| No | 97.0 | 94.5 | 98.9 | 99.3 | ||||

| Total sample size | 3,249 | 310 | 3,556 | 421 | ||||

| Suicide thoughts, past yr., Wave 3 | ||||||||

| Yes | 5.4 | 4.3 | .66 | .415 | 6.0 | 5.6 | .09 | .76 |

| No | 94.6 | 95.7 | 94.0 | 94.4 | ||||

| Total sample size | 3,153 | 301 | 3,482 | 407 | ||||

| Suicide attempts, past yr., Wave 3 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 1.0 | .03 | .861 | 1.6 | 2.1 | .83 | .362 |

| No | 99.0 | 99.0 | 98.4 | 97.9 | ||||

| Total sample size | 3,247 | 309 | 3,556 | 421 | ||||

| General Health | ||||||||

| Fair/poor | 4.6 | 7.9 | 2.14 | .144 | 4.3 | 6.2 | .88 | .346 |

| OK to excellent | 95.4 | 92.1 | 95.7 | 93.8 | ||||

| Total sample size | 871 | 101 | 871 | 113 | ||||

| Work/School Status | ||||||||

| Currently Working 10 Hours a Week | ||||||||

| Yes | 77.4 | 78.0 | 0.06 | 0.804 | 73.2 | 71.5 | 0.49 | 0.480 |

| No | 22.6 | 22.0 | 26.8 | 28.5 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,084 | 282 | 3,342 | 382 | ||||

| Males | Females | |||||||

| Characteristic (Wave 3) | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value | Intact Household | One or More Deceased Parents | Χ2 (df) | p-value |

| Attending college | ||||||||

| Not in school | 60.5 | 60.4 | 0.01 | 0.994 | 63.2 | 66.3 | 0.46 | 0.796 |

| Full time | 30.3 | 30.7 | 28.4 | 25.7 | ||||

| Part time | 9.2 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 8.0 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 870 | 101 | 871 | 113 | ||||

| Ever Married (at Wave 4) | ||||||||

| Never | 52.3 | 59.3 | 5.80 | 0.055 | 44.4 | 50.8 | 15.1 | 0.001 |

| Once | 45.3 | 38.8 | 51.6 | 42.8 | ||||

| Twice or more | 2.4 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 6.4 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 3,279 | 317 | 3,600 | 449 | ||||

| Premature Death | ||||||||

| Accident | 0.5 | 0.4 | 11.4 | 0.044 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 4.88 | 0.43 |

| Suicide | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Assault | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Natural Causes | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.3 | ||||

| Other | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | ||||

| Living | 98.7 | 97.6 | 99.5 | 99.2 | ||||

| Total Sample Size | 4,310 | 502 | 3,927 | 485 | ||||

| Males | Females | |||||||

| Characteristic | Mean Intact Household (SD) | Mean One or More Deceased Parents (SD) | F-test | p-value | Mean Intact Household (SD) | Mean One or More Deceased Parents (SD) | F-test | p-value |

| Highest Grade Completed | 13.36 (1.9) | 12.73 (1.8) | 30.9 | 0.0001 | 13.75 (2.0) | 12.95 (1.9) | 62.6 | 0.0001 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,250 | 309 | 3,553 | 421 | ||||

| Total Delinquency Score | 1.08 (2.4) | 1.07 (2.6) | 0.00 | 0.946 | 0.35 (1.2) | 0.43 (1.5) | 1.35 | 0.246 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,156 | 300 | 3,522 | 413 | ||||

| Total Violence Score | 0.27 (0.9) | 0.35 (1.1) | 2.61 | 0.107 | 0.06 (0.4) | 0.12 (0.6) | 7.99 | 0.0047 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,205 | 306 | 3,525 | 412 | ||||

| Total Depression Score | 2.47 (2.6) | 2.74 (2.8) | 3.17 | 0.075 | 3.07 (3.0) | 3.77 (3.4) | 19.6 | 0.0001 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,238 | 309 | 3,545 | 420 | ||||

| Self Esteem Total Score | 6.95 (2.3) | 6.84 (2.3) | 0.68 | 0.411 | 7.19 (2.6) | 7.21 (2.3) | 0.03 | 0.868 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,245 | 310 | 3,549 | 421 | ||||

| Problems with Friends | 0.17 (0.6) | 0.15 (0.5) | 0.54 | 0.463 | 0.095 (0.4) | 0.079 (0.4) | 0.59 | 0.444 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,236 | 309 | 3,545 | 420 | ||||

| Problems with School or Work | 0.08 (0.4) | 0.06 (0.4) | 0.43 | 0.513 | 0.05 (0.3) | 0.21 (0.2) | 2.22 | 0.137 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,236 | 308 | 3,552 | 420 | ||||

| Problem with Friends due to Drugs | 0.06 (0.4) | 0.07 (0.5) | 0.08 | 0.781 | 0.04 (0.3) | 0.02 (0.2) | 1.13 | 0.288 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,238 | 309 | 3,554 | 419 | ||||

| Dispossessed scale | 0.35 (0.8) | 0.51 (1.0) | 10.7 | 0.001 | 0.40 (0.9) | 0.56 (1.0) | 12.1 | 0.0005 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,213 | 308 | 3,501 | 418 | ||||

| Entitlements scale | 4.25 (1.7) | 3.67 (1.9) | 34.1 | 0.0001 | 4.46 (1.6) | 3.87 (2.0) | 48.1 | 0.0001 |

| Total Sample Size | 3,235 | 307 | 3,544 | 421 | ||||

The data on drug and alcohol use at Wave 3 yielded some surprising patterns. Both bereaved and non-bereaved young adults smoked cigarettes at approximately similar rates. For alcohol use and heavy (binge) drinking, both males and females who were parentally bereaved were significantly less likely to drink and to get drunk compared to their non-bereaved peers at Wave 3. Both male and female parentally bereaved young adults showed similar patterns with their non-bereaved peers in all other dimensions of substance use and problems: having problems with friends or work from heavy drinking, using marijuana, inhalants and use of all other illegal drugs.

The findings regarding psycho-social adjustments did not show parentally bereaved young adults to be substantially different from their non-bereaved peers. The bereaved young men were not significantly different from their non-bereaved male counterparts in levels of self-reported depression, though bereaved females still showed higher depression scores than the non-bereaved. Yet, between both genders, there were no differences in self-esteem scores, or suicidal thoughts or attempts between the bereaved and the non-bereaved. Both the bereaved young men and women showed no differences in seeking help from mental health counselors, compared to the non-bereaved. Despite this, bereaved males were significantly more likely to have been involved in drug rehabilitation and 12-step recovery programs, compared to non-bereaved males. Both the bereaved and non-bereaved young men and women reported their general health similarly at Wave 3.

When we examined educational attainments at Wave 3, statistically significant divergences were noted between the bereaved and the non-bereaved young adults. For the non-bereaved men and women, mean educational accomplishments were at the level of completing a year of college on average, compared to a rate of high school completion for the bereaved. At the time of the Wave 3 survey, approximately similar numbers of the bereaved and the non-bereaved reported going to school full time, part-time and/or being in the labor force.

At Wave 3 the bereaved reported diverging living arrangements compared to the non-bereaved. More bereaved females reported having lived in a homeless shelter, compared to their non-bereaved counterparts; bereaved males did not exhibit this pattern. More of both genders of the bereaved reported being ordered to move out from their parent’s homes. More bereaved of both genders reported having lived in a treatment center compared to the non-bereaved. More bereaved of both genders reported living in their own households, apart from parents at Wave 3. More bereaved males, but not females, reported living alone at Wave 3 compared to the non-bereaved. At Wave 3 the bereaved of both genders also reported more experiences of being dispossessed and of having fewer material advantages, compared to the non-bereaved on our scales.

We also examined whether the bereaved showed differences in ever having been married by Wave 4. For both genders it appeared there were fewer bereaved reporting having ever married by Wave 4, when respondents were between the ages 25 and 33. For the males delay of marriage bordered on statistical significance, while bereaved women were clearly less likely to have been married. We also investigated whether the bereaved were more likely to die prematurely. This appeared to be true only for the males.

In Table 2 there were 16 bivariate associations with parental death that had achieved statistical significance. Once again we used OLS to investigate correlates of interest controlling for social class and minority status. In cases where a dichotomous outcome variable was examined, a logistic regression model was employed. We converted variables that were not scalar, such as different causes of death, into a 1 vs. 0 format, died vs. alive. Of the 16 associations we examined, nine remained statistically significant when controls for social class and racial minority status were applied. They were as follows: educational attainment, parents ordered the child to move out, ever lived in a treatment center, lived with parents or independently, lived alone (males only), material advantages, being dispossessed, depression score (females only), and ever marrying.

Discussion

This analysis confirms findings from many studies showing adjustment problems among adolescents surviving the childhood death of one or both parents. Heightened depression, increased suicidality, diminished self-esteem, heightened delinquency, criminal behavior, substance abuse and diminished academic achievements all appear to be correlated with parental death using data from the Add Health longitudinal survey. Using this survey we tracked respondents over seven years, as they entered adulthood, when they ranged in age from 18 to 26. At this point, we discovered a new patterns of associations, but with the exception of depression among females only, most of the earlier youth adjustment problems correlates had faded by that point in time. These same parentally bereaved young adults did not show any self-esteem deficits (compared to their non-bereaved peers living in intact two-parent homes). Their use of drugs, suicidality, criminal involvements, use of mental health services and other facets of psycho-social adjustments matched those of their non-bereaved peers. These results suggest resilience among parentally bereaved youth, adapting to their loss circumstances and to the power of time-after-loss, to advance a mourner’s healing.

It should also be noted that as young adults these parentally bereaved casualties experienced some lasting socio-economic disadvantages, possibly due to greater previously reported school problems and premature school withdrawals. By Wave 3 they reported one year less of formal education than their non-bereaved counterparts. Although the data did not show bereaved young adults as any less inclined to hold a job holding or to go to school at Wave 3, the bereaved were more likely to be lacking in material advantages and more likely to have been dispossessed by being denied credit, phone or utility services. These patterns held up even after controls for racial minority membership and social class were applied. An additional challenge confronted these less financially able young adults, with more of them living independently from their parents compared to their non bereaved peers.

Another important correlate we observed was that more parentally bereaved young men and women reported being forced out of their parental homes, suggesting more familial conflict and discord with their surviving parents. Previous research has documented greater and persisting conflict with biological parents following a parent’s divorce (Amato & Keith, 1991). It seems plausible to anticipate that a parent’s death might evoke similar strains and impairments in family relations and this strikes us as a worthy subject for future research on bereaved children. At Wave 1 the Add Health data showed more parentally bereaved youth having less harmonious relations with mothers and fathers compared to their peers in intact biological parent families, even when controlling for class and race. Unfortunately, at Wave 3 this subject was not examined with the same depth and precision as it had been a Wave 1. Future research may find it useful to further investigate the quality and transformations in parent/ child relationships with remaining parents after one parent’s death.

In any longitudinal study there is always the possibility that respondents not participating in later follow-up interviews could be more dysfunctional in comparison with those participating, which would bias our findings in the directions we observed. We cannot discount this possibility altogether. Had interview refusal rates been similar between participating sample subgroups this possibility could have been discredited. Yet, in examining interview participation rates we found differences with respondents from two-parent biological families showing a 9% higher participation rate at Wave 3 compared to respondents in re-constituted parental families and an 11% percent higher rate compared that for parentally bereaved youth. Survey decedents, more than 100 of whom had died by the Wave 3 interview, were disproportionally drawn from the ranks of those in re-constituted and parentally bereaved families. These differing interview participation rates still suggest a certain tentativeness to our findings. It will be task of future research to confirm these observations.

Should these findings be confirmed in future research it will not be altogether surprising. Many studies from different countries, drawing upon diverging bereavement populations, have already confirmed diminishing bereavement distress and lessening problematic adjustments with increased time after a loss (Bonanno, 2009; Dyregrov & Dyregrov, 1999; Kreicbergs, Lannen, Onelov, & Wolfe, 2007; Levi-Belz,.2015; Ott, Lueger, Keller & Prigerson, 2007). It appears readily understandable that young adults will generally become more resilient with the passage of time after a parent’s death.

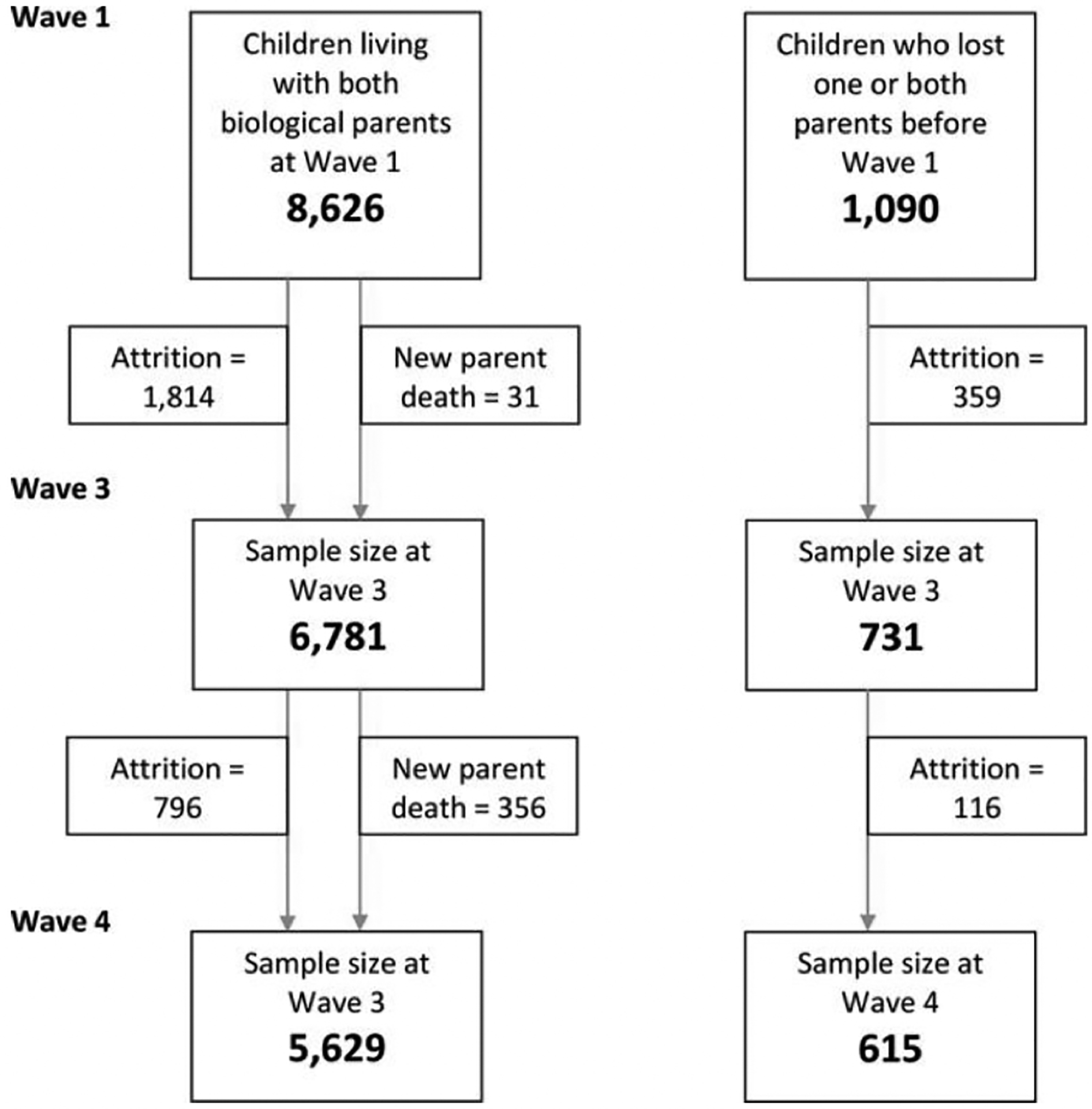

Figure 1.

flowchart of respondent attrition among those living with both biological parents and those losing a parent from wave 1 to wave 3

Acknowledgments:

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

Contributor Information

William Feigelman, Nassau Community College, Garden City, NY 11530..

Zohn Rosen, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Thomas Joiner, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL.

Caroline Silva, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL.

Anna S. Mueller, Department of Comparative Human Development, University of Chicago, Chicago Il.

References

- Amato PR. & Keith B (1991) Parental Divorce and the Weil-Being of Children: A Meta-Analysis Psychological Bulletin, 110, 26–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg L Rostila M Saarela J & Hjern A (2014) Parental death and subsequent school performance Pediatrics. 133, 682–689.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA (2009) The other side of sadness: What the new science of bereavement tells us about life after loss. NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cerel J, Fristad MA, Verducci J, Weller RA, & Weller EB (2006). Childhood bereavement: Psychopathology in the 2 years postparental death. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdney L (2000) Annotation: Childhood bereavement following parental death. Journal of Child Psychol. Psychiat 41, 819–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper A & Hancock M (2011) Childhood parental bereavement: the risk of vulnerability to delinquency and factors that compromise resilience Mortality, 16, 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Dyregrov A, & Dyregrov K. (1999) Long-term impact of sudden infant death: a 12- to 15-year follow-up Death Studies. 23, 635–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreicbergs UC, Lannen P, Onelov E, & Wolfe J (2007).Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 25, 3307–3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J & Bovasso G ((2009) Re-examining the long-term effects of experiencing parental death in childhood on adult psychopathology. J Nerv Ment Dis.,197, 24–27.doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181927723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen I & Christiansen E (2011) Young people’s risk of suicide attempts in relation to parental death: a population-based register study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry.52,176–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02298.x. Epub 2010 Oct 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Belz Y(2015) Stress-Related Growth among Suicide Survivors: The Role of Interpersonal and Cognitive Factors. Arch Suicide Res.19,305–20. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2014.957452. Epub 2014 Dec 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J Verergaard M Cnattingius S, Gissler M Hammer Bech B, Obel C & Olsen J Mortality after parental death in childhood: A nationwide cohort study in three Nordic countries Plos. July 22, 2014, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed,1001679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweis M Solomon F & Green M Eds. (1984) Bereavement Reactions, Consequences and Care Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Chapter 5, Bereavement During Childhood and Adolescence. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott CH, Lueger RJ Kelber ST & Prigerson HG (2007) Spousal bereavement in older adults: Common, resilient and common grief with defining characteristics. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 195, 332–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I Ma Y Tein J Ayers T, Wolchik S Kennedy C & Millsap R (2010) Long-term effects of the family bereavement program on multiple indicators of grief in parentally bereaved children and adolescents Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2010, 78, 131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stikkelbroek Y, Prinzie P, de Graaf R, Ten Have M, & Cuijpers P. (2012) Parental death during childhood and psychopathology in adulthood. Psychiatry Res. 198, 516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.024. Epub 2012 Mar 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Administration. (2000) Intermediate assumptions of the 2000 Trustees Report., Washington, DC: Office of the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant C, Bebbington P & Hurry J (1980) Parental death in childhood and risk of adult depressive disorders: a review. Psychological Medicine, 10,1980, pp 289–299 DOI: 10.1017/S0033291700044044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Kaslow N, Kingree J, King M, Bryant L &, Rey M.(1998) Psychological symptomatology following parental death in a predominantly minority sample of children and adolescents. J Clin Child Psychol. 27, 434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder E, Sandler I, Wolchik S & MacKinnon D (2011) Quality of Social Relationships and the Development of Depression in Parentally-Bereaved Youth. J Youth Adolescence. 40:85–96 DOI 10.1007/s10964-009-9503-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Sydow K,Lieb R,Pfister H,Höfler M, & Wittchen H(2002) What predicts incident use of cannabis and progression to abuse and dependence?: A 4-year prospective examination of risk factors in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 68, 49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox H, Kuramoto S Lichtenstein P, Långström N Brent D & Runeson B(2010) Psychiatric Morbidity, Violent Crime, and Suicide Among Children and Adolescents Exposed to Parental Death. Journal of Amer. Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 49, 514–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worden W & Silverman P (1996) Parental death and the adjustment of school aged children. Omega 33, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yagla Mack K (2001) Childhood family disruptions and adult well-being: The differential effects of divorce and parental death. Death Studies. 25, 419–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]