Abstract

Background

The Bergamo province, which is extensively affected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic, is a natural observatory of virus manifestations in the general population. In the past month we recorded an outbreak of Kawasaki disease; we aimed to evaluate incidence and features of patients with Kawasaki-like disease diagnosed during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic.

Methods

All patients diagnosed with a Kawasaki-like disease at our centre in the past 5 years were divided according to symptomatic presentation before (group 1) or after (group 2) the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Kawasaki- like presentations were managed as Kawasaki disease according to the American Heart Association indications. Kawasaki disease shock syndrome (KDSS) was defined by presence of circulatory dysfunction, and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) by the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation criteria. Current or previous infection was sought by reverse-transcriptase quantitative PCR in nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, and by serological qualitative test detecting SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG, respectively.

Findings

Group 1 comprised 19 patients (seven boys, 12 girls; aged 3·0 years [SD 2·5]) diagnosed between Jan 1, 2015, and Feb 17, 2020. Group 2 included ten patients (seven boys, three girls; aged 7·5 years [SD 3·5]) diagnosed between Feb 18 and April 20, 2020; eight of ten were positive for IgG or IgM, or both. The two groups differed in disease incidence (group 1 vs group 2, 0·3 vs ten per month), mean age (3·0 vs 7·5 years), cardiac involvement (two of 19 vs six of ten), KDSS (zero of 19 vs five of ten), MAS (zero of 19 vs five of ten), and need for adjunctive steroid treatment (three of 19 vs eight of ten; all p<0·01).

Interpretation

In the past month we found a 30-fold increased incidence of Kawasaki-like disease. Children diagnosed after the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic began showed evidence of immune response to the virus, were older, had a higher rate of cardiac involvement, and features of MAS. The SARS-CoV-2 epidemic was associated with high incidence of a severe form of Kawasaki disease. A similar outbreak of Kawasaki-like disease is expected in countries involved in the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic.

Funding

None.

Introduction

The epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), causing COVID-19, has rapidly spread worldwide. Italy was the first European country to be affected, with the outbreak estimated to have started in February, 2020. Currently, Italy has reported 132 547 COVID-19-positive cases, 51 534 of which are in Lombardy.1 It is estimated that at least 10% of the Italian population—ie, approximately 1 million people—have been exposed to the virus.2 The city of Bergamo has the highest rate of infections and deaths in Italy, which makes the province of Bergamo a natural epidemiological setting where SARS-CoV-2 infections appeared earlier and were more evident.

In adults, COVID-19 is typically characterised by severe interstitial pneumonia and hyperactivation of the inflammatory cascade.3, 4 In children, the respiratory involvement appears to have a more benign course, with almost no fatalities reported in this age group.5, 6, 7 Nonetheless, the respiratory tract seems not to be the only system susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection.8 Increasing evidence suggests that tissue damage in COVID-19 is mostly mediated by the host innate immunity.9, 10 This disease is characterised by a cytokine storm resembling that of macrophage activation seen in viral-induced haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.11

Kawasaki disease is an acute and usually self-limiting vasculitis of the medium calibre vessels, which almost exclusively affects children.12, 13 In the acute phase of the disease, patients with Kawasaki disease might have haemodynamic instability, a condition known as Kawasaki disease shock syndrome (KDSS).14 Other patients with Kawasaki disease might fulfil the criteria of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), resembling secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.15 The cause of Kawasaki disease remains unknown; however, earlier evidence16 suggests that an infectious agent triggers a cascade that causes the illness.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Kawasaki disease is an acute self-limiting vasculitis with specific predilection for the coronary arteries that affects previously healthy young infants and children. Despite half a century having passed since Kawasaki disease was first reported in Japan, the cause of this condition remains unknown. We did a PubMed database search to identify studies investigating the cause and pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease using the terms “Kawasaki disease”, “etiology”, “pathogenesis”, “intravenous immunoglobulin”, “corticosteroids”, “macrophage activation syndrome (MAS)”, and “KD shock syndrome”. All relevant articles were evaluated. The most accepted pathogenetic hypothesis supports an aberrant response of the immune system to one or more unidentified pathogens in genetically predisposed subjects. An infectious trigger, however, has not been identified.

Added value of this study

Shortly after the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to our region (Bergamo, Italy), we found a 30-fold increased incidence of Kawasaki disease. Children diagnosed after the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic began showed evidence of immune response to the virus, were older, had a higher rate of cardiac involvement, and features of MAS. We therefore showed that SARS-CoV-2 might cause a severe form of Kawasaki-like disease.

Implications of all the available evidence

Outbreaks of Kawasaki-like disease might occur in countries affected by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, and might present outside the classic Kawasaki disease phenotype. This condition might be serious and requires prompt and more aggressive management. Future research on the cause of Kawasaki disease and similar syndromes should focus on immune responses to viral triggers.

The aim of this study was to describe the incidence and features of new cases of Kawasaki-like presentations admitted to our unit during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic.

Methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the notes of patients diagnosed with Kawasaki disease admitted to the General Paediatric Unit of Hospital Papa Giovanni XXIII (Bergamo, Italy), between Jan 1, 2015, and April 20, 2020. Our unit is a tertiary paediatric referral centre with approximately 1300 paediatric admissions per year, serving a province of approximately 1 million people, and hosting the largest Italian paediatric liver transplant programme and the largest paediatric intensive care unit of northern Italy (16 beds). In the general paediatric unit, there are paediatric consultants fully trained in all paediatric subspecialties.

Patients with Kawasaki-like presentations were defined according to the 2017 criteria of the American Heart Association, including both the classic type (fever for ≥5 days plus four or more clinical criteria, including bilateral bulbar non-exudative conjunctivitis, changes of the lips or oral cavity, non-suppurative laterocervical lymphadenopathy, polymorphic rash, erythema of the palms and soles, firm induration of the hands or feet, or both) and incomplete types. In incomplete types (fever for ≥5 days plus two or three of the aforementioned clinical criteria), the values of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP), or both, were taken as an additional diagnostic criterion in association with the presence of anaemia, thrombocytosis after 7 days of fever, hypoalbuminaemia, hypertransaminasaemia, leucocytosis, sterile pyuria, or an echocardiogram showing coronary aneurysms or cardiac dysfunction (ie, left ventricular function depression, mitral valve regurgitation, or pericardial effusion).17 All patients were diagnosed and managed by LV, who has been in charge of paediatric rheumatology in the Paediatric Department since 2010.

KDSS was defined as Kawasaki disease accompanied by systolic arterial hypotension, a decrease from basal systolic blood pressure of at least 20%, or the appearance of signs of peripheral hypoperfusion.14 Ejection fraction, and concentrations of troponin I and pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (proBNP) were measured and used as indirect signs of myocarditis and heart failure.

MAS was defined using the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation criteria18 for the classification of MAS in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The MAS criteria are validated for systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, but they are commonly used for other systemic autoinflammatory diseases such as Kawasaki disease and paediatric systemic lupus erythematosus.19

We divided the patients in two groups according to the date of presentation: group 1, presenting during the 5 years preceding the local SARS-CoV-2 epidemic (ie, Jan 1, 2015, to Feb 17, 2020); and group 2, presenting thereafter (ie, Feb 18 to April 20, 2020).

Clinical and laboratory evaluation

Data were obtained from hospital medical records, and included demographic data, presenting symptoms and history of previous treatments, contact with confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19, vital signs, and laboratory data, including white blood cell count, lymphocyte count, ESR, CRP, procalcitonin, ferritin, fibrinogen, proBNP, troponin I, natural killer (NK) activity, and concentrations of interleukin 6 (IL-6). Electrocardiogram and echocardiogram were done in all children.

Confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection

Patients and caregivers had nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab sampling, testing SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid using reverse-transcriptase quantitative PCR assay; patients with a positive nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab sampling test were considered confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The patients diagnosed more recently had a test for the qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (IgM and IgG) through a lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay (NADAL COVID-19 IgG/IgM Test, Nal Von Minden, Moers, Germany). Positivity for IgM or IgG, or both, was considered consistent with an earlier infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Treatment

Risk of resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin treatment was ascertained according to the Kobayashi score.20 All patients were administered intravenous immunoglobulin at 2 g/kg. According to the RAISE study,20 based on risk stratification, patients were also treated with aspirin at 50–80 mg/kg per day (Kobayashi score <5) for 5 days or aspirin at 30 mg/kg per day plus methylprednisolone at 2 mg/kg per day for 5 days (Kobayashi score ≥5), followed by a tapering of methylprednisolone over 2 weeks. Aspirin was maintained until 48 h after defervescence, and then continued at an antiplatelet dose of 3–5 mg/kg per day for 8 weeks.20 The schedule for patients at risk of intravenous immunglobulin resistance was adopted also in patients with KDSS or MAS. Response to treatment was defined as the normalisation of vital signs, CRP, and blood tests, and the resolution of symptoms and signs.

Statistical analysis

The Student's t test, the χ2 method, and Fisher's exact test were done when appropriate for statistical analysis to compare continuous and categorical variables. A p value of <0·05 was chosen as cutoff for significance. Data were analysed with SPSS (version 20.0) and GraphPad Prism (version 5.00 for Mac). The study was approved by the Bergamo Ethics Committee (registration number 37/20, 25/03/2020).

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Between Feb 18 and April 20, 2020, ten patients (aged 7·5 years [SD 3·5]; seven boys, three girls), were diagnosed with Kawasaki disease (incidence ten per month), and comprised group 2. Admission to hospital occurred, on average, on day 6 of fever (range 4–8). Five (50%) patients presented with a classic form of the disease, and five (50%) presented with an incomplete form. Patients presenting with the classic form had non-exudative conjunctivitis, hand and feet anomalies (ie, erythema or firm induration, or both), and polymorphic rash. Four (80%) of five patients had associated changes of the lips or oral cavity, or both; patient 7 also had laterocervical lymphadenopathy (table 1 ).

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory features of ten patients with Kawasaki-like disease who presented over 1 month during SARS-CoV-2 epidemic (group 2)

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | Patient 9 | Patient 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of onset | March 17, 2020 | March 27, 2020 | March 28, 2020 | April 3, 2020 | April 3, 2020 | April 4, 2020 | April 6, 2020 | April 10, 2020 | April 11, 2020 | April 14, 2020 | |

| Age, years | 8·2 | 7·0 | 2·9 | 7·7 | 7·5 | 16·0 | 5·0 | 9·2 | 5·5 | 5·5 | |

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Female | Female | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male | |

| Type of Kawasaki disease | Incomplete | Incomplete | Classic | Incomplete | Incomplete | Classic | Classic | Incomplete | Classic | Classic | |

| Other symptom | .. | Diarrhoea, meningeal signs | .. | Diarrhoea, meningeal signs | Diarrhoea | Diarrhoea | Meningeal signs | Diarrhoea | Meningeal signs | Diarrhoea, drowsiness | |

| ESR, mm/h | .. | 60 | 39 | 108 | 97 | .. | 51 | 84 | 81 | 54 | |

| Lymphocytes, × 109 per L | 803 | 1060 | 970 | 930 | 450 | 790 | 1870 | 860 | 420 | 460 | |

| Blood culture | .. | Sterile | Sterile | Sterile | Sterile | Sterile | Sterile | Sterile | Sterile | Sterile | |

| Chest x-ray | Pneumonia | Pneumonia | Pneumonia | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Pneumonia | Normal | Pneumonia | |

| Echocardiography | Abnormal | Normal | Normal | Abnormal | Abnormal | Abnormal | Normal | Abnormal | Normal | Abnormal | |

| Aneurism | >4 mm | No | No | No | No | No | No | >4 mm | No | No | |

| Ejection fraction | 48% | >55% | >55% | 25% | 30% | >55% | >55% | 40% | >55% | 45% | |

| Mitral valve regurgitation | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | |

| Pericardial effusion | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | |

| Kobayashi ≥5 | Yes (6) | Yes (6) | No (4) | Yes (6) | Yes (6) | No (3) | No (2) | Yes (6) | Yes (6) | Yes (6) | |

| <12 months | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Kawasaki disease signs at day 4 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| CRP ≥10 mg/dL | Yes (0·9) | Yes (31·1) | Yes (15·2) | Yes (48·0) | Yes (52·5) | No (7·3) | Yes (24·0) | Yes (24·2) | Yes (24·6) | Yes (12·2) | |

| Neutrophils ≥80% | Yes (80·0) | Yes (89·7) | No (77·3) | Yes (90·0) | Yes (90·5) | No (79·4) | No (77·9) | Yes (91·9) | Yes (85·5) | Yes (83·0) | |

| Platelets ≤300 × 109 per L | Yes (119) | Yes (121) | Yes (66) | Yes (142) | Yes (113) | Yes (121) | Yes (138) | Yes (192) | Yes (151) | Yes (142) | |

| Sodium ≤133 mEq/L | Yes (131) | Yes (130) | Yes (132) | Yes (128) | Yes (129) | No (135) | No (135) | Yes (133) | Yes (133) | Yes (122) | |

| ALT ≥100 U/L | No (32) | No (79) | No (46) | No (82) | No (78) | Yes (733) | No (41) | No (63) | No (20) | No (20) | |

| MAS18 | .. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | |

| Ferritin >684 ng/mL | .. | Yes (1183) | Yes (893) | Yes (1972) | Yes (3213) | Yes (2027) | No (199) | No (449) | No (307) | No (341) | |

| Platelets ≤181 × 109 per L | Yes (119) | Yes (121) | Yes (66) | Yes (142) | Yes (113) | Yes (121) | Yes (138) | No (192) | Yes (151) | Yes (142) | |

| AST >48 IU/L | No (30) | Yes (120) | Yes (63) | Yes (174) | Yes (89) | Yes (237) | Yes (50) | Yes (51) | No (29) | No (30) | |

| Triglycerides ≥156 mg/dL | − | Yes (434) | Yes (367) | Yes (263) | Yes (198) | .. | Yes (161) | Yes (200) | Yes (171) | No (121) | |

| Fibrinogen ≤360 mg/dL | No (465) | No (599) | No (506) | No (924) | No (759) | Yes (313) | No (637) | No (759) | No (759) | No (489) | |

| KDSS14 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Hypotension | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| SBP ≤20% basal | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Peripheral hypoperfusion | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| CPK, nv 461–71 IU/L | 16 | 84 | 76 | 247 | 89 | 119 | 79 | 40 | 59 | 40 | |

| Troponin I, nv ≤53 ng/L | 111 | 188 | − | 200 | 3557 | 4906 | 12 | 36 | <3 | 23 | |

| proBNP, nv 1–00 ng/L | 1870 | 952 | 1519 | 2072 | 1665 | 108 | 347 | 2957 | 139 | 927 | |

| Nasal swab for respiratory pathogens | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | |

| Nasal swab for SARS-CoV-2 | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | |

| Serology for SARS-CoV-2 (IgG, IgM) | Negative, negative | Positive, negative | Positive, negative | Positive, positive | Positive, positive | Negative, negative* | Positive, negative | Positive, negative | Positive, positive | Positive, negative | |

| Serology (days from onset) | 30 | 18 | 16 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 6 | |

| Contact with suspected or confirmed case | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Caregiver nasal swab for SARS-CoV-2 | .. | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Positive | |

| Treatment | IVIG plus aspirin | IVIG plus mPDN | IVIG plus mPDN | IVIG plus mPDN | IVIG plus mPDN | IVIG plus mPDN | IVIG plus aspirin | IVIG plus mPDN | IVIG plus mPDN | IVIG plus mPDN | |

| Inotropes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Response | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

ESR=erythrocyte sedimentation rate. CRP=C-reactive protein. MAS=Macrophage Activation Syndrome. ALT=alanine aminotransferase. AST=aspartate aminotransferase. KDSS=Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. SBP=systolic blood pressure. CPK=creatine phosphokinase. BNP=B-type natriuretic peptide. nv=normal values. SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. IVIG=intravenous immunoglobulin. mPDN=methylprednisolone.

Test done shortly after high-dose IVIG.

In group 2, five (50%) of ten patients were diagnosed with incomplete Kawasaki disease, presenting with three or fewer clinical criteria associated with additional laboratory criteria (n=1) or an abnormal echocardiography (n=4). Two (20%) patients had bulbar non-exudative conjunctivitis; changes of the lips or oral cavity, or both; and polymorphic rash. One (10%) patient had only bulbar non-exudative conjunctivitis and polymorphic rash. In two (20%) patients, the echocardiography detected a left coronary aneurysm (>4 mm), reduced ejection fraction (48% and 40%), and mitral valve regurgitation; patient 1 also had pericardial effusion. Patient 2 met the diagnosis with four additional laboratory criteria (ie, hypoalbuminaemia, hypertransaminasaemia, leucocytosis, and sterile pyuria).

Patients 4 and 5 diagnosed with incomplete Kawasaki disease, presented with non-exudative conjunctivitis associated with changes in the lips and oral cavity (patient 4), or polymorphic rash (patient 5). In these patients, echocardiography revealed left ventricular function depression, mitral valve regurgitation, and pericardial effusion; they also required inotropic support. Patient 4 had an underlying diagnosis of congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Chest x-ray, done in all patients in group 2, was positive in five (50%) patients for minimal mono or bilateral infiltrates. Patients 1 and 10 had a chest CT and a confirmed bibasilar pulmonary thickening. Patients 2 and 7, who had meningeal signs, had an electroencephalogram that showed a slow wave pattern; patient 7 had a lumbar puncture revealing normal cerebrospinal fluid and the absence of SARS-CoV-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Five (50%) of ten patients in group 2 met the criteria for KDSS because of hypotension and clinical signs of hypoperfusion. Two (20%) patients had diarrhoea and meningeal signs, four (40%) had only diarrhoea, and two (20%) had only meningeal signs (table 1). Mean ESR was 72 mm/h (SD 24), mean CRP 25 mg/dL (SD 15·3), and mean ferritin 1176 ng/mL (SD 1032). Full blood count showed a mean white cell count of 10·8 × 109 per L (SD 6·1), with increased neutrophil percentage in eight patients (84·5% [SD 5·7]), lymphopenia in eight patients (0·86 × 109 per L [SD 0·40]), and thrombocytopenia in eight patients (130 × 109 per L [32]). Hyponatraemia (≤133 mEq/L) was observed in eight patients (131 mEq/L [SD 4]) and a slight increase in transaminases was recorded in seven patients (aspartate aminotransferase 87 U/L [SD 70]; alanine aminotransferase 119 U/L [217]).

Hypertriglyceridaemia was shown in seven (87%) of eight tested patients in group 2 (239 mg/dL [SD 108]); fibrinogen was high in nine (90%) of ten patients (621 mg/dL [182]), as was D-dimer in eight (80%) of ten patients (3798 ng/mL [SD 1318]). Laboratory criteria predicted intravenous immunoglobulin-resistance in seven (70%) of ten patients. MAS was diagnosed in five (50%) of ten patients. Troponin I was elevated in five (55%) of nine tested patients (1004 ng/L [SD 1862]), creatine phosphokinase in one (10%) of ten patients (85 IU/L [64]), and proBNP in all ten patients (1255 ng/L [929]; Table 1, Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Comparison between patients with Kawasaki-like disease presenting before and after the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic

| Group 1 | Group 2 | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of presentation | Until February, 2020 | March–April, 2020 | NA | |

| Number of patients | 19 | 10 | NA | |

| Age at onset, years | 3·0 (2·5) | 7·5 (3·5) | 0·00035 | |

| Incidence | 0·3 per month | 10 per month | <0·00001 | |

| Sex | NA | NA | 0·13 | |

| Female | 12 | 3 | NA | |

| Male | 7 | 7 | NA | |

| Incomplete Kawasaki disease | 6/19 (31%) | 5/10 (50%) | 0·43 | |

| CRP, mg/dL | 16·3 (8·0) | 25 (15·3) | 0·05 | |

| ESR, mm/h | 82 (29) | 72 (24) | 0·38 | |

| White cell count, × 109 per L | 19·4 (6·4) | 10·8 (6·1) | 0·0017 | |

| Neutrophils | 71·9% (17·2) | 84·5% (5·7) | 0·034 | |

| Lymphocytes, × 109 per L | 3·0 (1·8) | 0·86 (0·4) | 0·0012 | |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 10·8 (2·0) | 11 (1·2) | 0·79 | |

| Platelets, × 109 per L | 457 (96) | 130 (32) | <0·00001 | |

| Albumin, g/dLl | 3·3 (0·5) | 3·2 (0·3) | 0·55 | |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 134·7 (1·6) | 130·8 (3·9) | 0·0011 | |

| AST, U/L | 120 (218) | 87 (70) | 0·64 | |

| ALT, U/L | 92 (122) | 119 (217) | 0·67 | |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 187 (89) | 1176 (1032) | 0·011 | |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | .. | 239 (108) | .. | |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 543 (300) | 621 (182) | 0·51 | |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 3244 (943) | 3798 (1318) | 0·52 | |

| CPK, IU/L | 61 (28) | 85 (64) | 0·19 | |

| Troponin I, ng/L | .. | 1004 (1862) | .. | |

| proBNP, ng/L | .. | 1255 (929) | .. | |

| Kobayashi score ≥5 | 2/19 (10%) | 7/10 (70%) | 0·0021 | |

| MAS18 | 0/10 (0%) | 5/10 (50%) | 0·021 | |

| KDSS14 | 0/10 (0%) | 5/10 (50%) | 0·021 | |

| Abnormal echocardiography | 2/19 (10%) | 6/10 (60%) | 0·0089 | |

| Adjunctive steroid treatment | 4/19 (16%) | 8/10 (80%) | 0·0045 | |

| Inotropes treatment | 0/19 (0%) | 2/10 (20%) | 0·11 | |

| Response to treatment | 19/19 (100%) | 10/10 (100%) | 1 | |

Data are mean (SD) or n/N (%), unless otherwise stated. SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. NA=not applicable. CRP=C-reactive protein. ESR=erythrocyte sedimentation rate. AST=aspartate aminotransferase. ALT=alanine aminotransferase. CPK=creatine phosphokinase. BNP=B-type natriuretic peptide. MAS=Macrophage Activation Syndrome. KDSS=Kawasaki disease shock syndrome.

For four (40%) of ten patients in group 2, IL-6 was increased (177·1 pg/mL [SD 137·4], normal values (nv) <3·4). NK count was measured in four (40%) patients, and was reduced in all (62 [SD 35]; nv 200–600 × 109 per L). Blood culture was sterile in all patients.

Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab sampling for SARS-CoV-2, available from Feb 24, 2020, was positive in two (20%) of ten patients in group 2 (table 1). All patients were tested at least twice. Serology for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, available from April 13, 2020, was investigated in all patients in group 2; eight (80%) of ten patients were IgG positive, and three were also IgM positive. Patient 6, who had a negative serology, was tested shortly after the infusion of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (table 1).

On April 14, 2020, 31 health-care personnel from the Paediatric Department, Hospital Papa Giovanni XXIII (Bergamo, Italy) had serology testing. Nine (29%) of 31 were IgG positive, and three (10%) were also IgM positive, corresponding to the expected rate of exposure of our local heath-care personnel to SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, two patients from group 1 diagnosed before the start of the epidemic were contacted and tested for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, and both were negative. To date, all patients in group 2 have been discharged, treatment with aspirin at an antiplatelet dose is ongoing, and a follow-up echocardiogram is scheduled at 8 weeks.

From Jan 1, 2015, to the start of the epidemic on Feb 17, 2020, 19 children were diagnosed with Kawasaki disease (incidence 0·3 per month; mean age 3 years [SD 2·5]; seven boys, 12 girls); these patients comprised group 1. Admission to hospital occurred, on average, on day 6 of fever (range 4–11 days). 13 (68%) of 19 patients presented with a classic form of the disease, and six (31%) of 19 with an incomplete form. None of the patients had hypotension, clinical signs of hypoperfusion, or other atypical symptoms. Laboratory criteria predicted intravenous immunoglobulin resistance in two (10%) of 19 patients. MAS was not diagnosed in any of the patients. A full comparison of clinical and biochemical characteristics of the two groups is provided in table 2. All patients included had a favourable outcome. Patients in group 1 had concluded their treatment and follow-up period, and recovered completely with no residual coronary artery aneurisms.

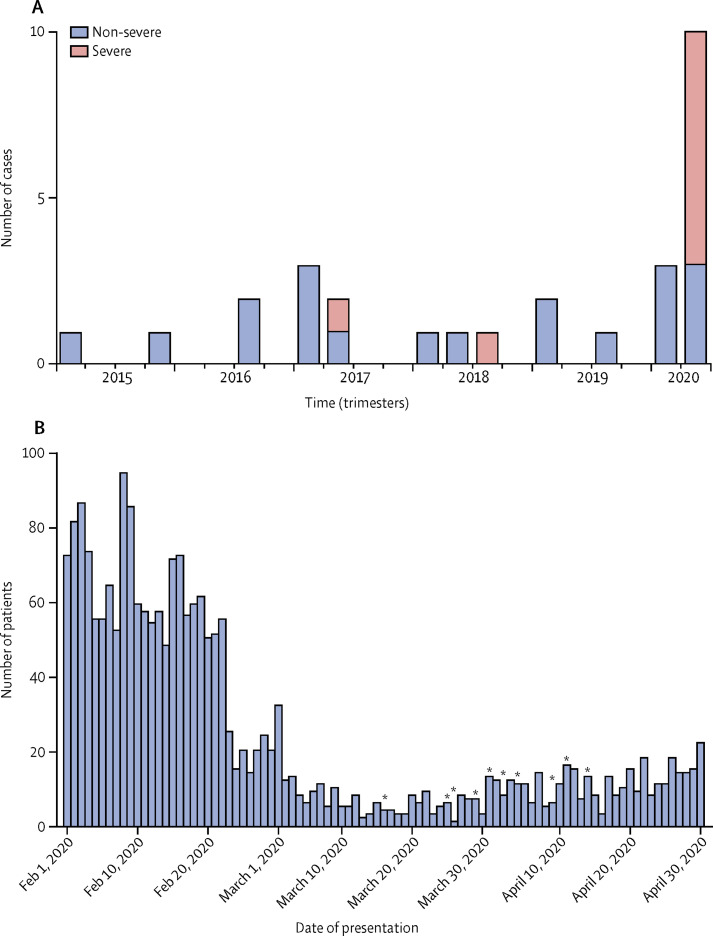

Group 1 comprised 19 patients diagnosed over 5 years, whereas group 2 included ten patients diagnosed over 1 month (incidence 0·3 per month vs ten per month; p<0·0001; table 2; figure ). To rule out the possible effect of number of referrals to the emergency department in different periods, we calculated incidence corrected for number of patients seen at the emergency department. We found that in the past 5 years, from January, 2015, to December, 2019, 98 572 patients had been evaluated, with a mean of 1642 (SD 280) per month, compared with 283 patients per month during the study period—approximately six-fold lower. With these figures, the incidence of Kawasaki disease in group 1 was 0·019% (95% CI −0·002 to 0·0019), compared with 3·5% (−3·5 to 3·6) in group 2 (odds ratio 184; p<0·0001; figure). To rule out the possible effect of a change in the geographical catchment area in the prepandemic (group 1) versus the pandemic (group 2) period, we reviewed the place of residence of all our patients with Kawasaki disease and drew a referral map, showing that all but one came from the Bergamo province (appendix p 1).

Figure.

Incidence of Kawasaki disease in the study period and in the past 5 years

(A) Frequency of Kawasaki disease at the paediatric emergency department of Hospital Papa Giovanni XXIII of Bergamo, Italy, in the past 5 years, by case severity. (B) Number of patients presenting to the paediatric emergency department during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 epidemic, and date of presentation of ten patients with Kawasaki-like disease (indicated by asterisks).

The average age at onset was 3·0 years (SD 2·5) in group 1 versus 7·5 years (3·5) in group 2 (p=0·0003). In group 1, 14 of 19 patients were white, versus eight of ten patients in group 2. The mean body-mass index of patients in group 1 was 15·93 kg/m2 (SD 1·72) versus 19·11 kg/m2 (SD 3·21) in group 2 (p=0·0016). Two patients tested in group 1 had a negative serology for SARS-CoV-2 versus eight of ten positive patients in group 2 (one of the two negative patients was tested after high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin); five (50%) of ten patients had been in contact with confirmed COVID-19 cases. Group 2 had a significantly lower white cell count, lymphocyte count, and platelet count when compared with group 1 (table 2). Group 2 also differed significantly from group 1 for increased rate of markers of severity. An abnormal echocardiogram was recorded in six (60%) of ten patients of group 2 versus two (10%) of 19 patients in group 1 (p=0·0089); fulfilment of criteria for KDSS and MAS was found in five (50%) of ten patients in group 2, and in none of the patients in group 1 (p=0·021). Seven (70%) patients in group 2 met the criteria for a Kobayashi score of 5 or more, compared with two (10%) of 19 patients in group 1 (p=0·0021). Adjunctive steroid treatment was required in four (16%) of 19 patients in group 1 versus eight (80%) of ten patients in group 2 (p=0·0045; table 2).

Discussion

Despite half a century having passed since Tomisaku Kawasaki first reported his 50 cases in Japan,12 the cause of Kawasaki disease remains unknown. The most accepted hypothesis supports an aberrant response of the immune system to one or more unidentified pathogens in genetically predisposed patients;21, 22, 23 however, the search for the infectious triggers has been disappointing.24 In Japan, during three epidemics recorded in 1979, 1982, and 1986, the highest Kawasaki disease incidence was seen in January, potentially suggesting that factors during winter months may trigger Kawasaki disease.25, 26 In 2010, the incidence of Kawasaki disease in Japan was 239·6 per 100 000 children younger than 5 years, compared with 20·8 per 100 000 in the USA.27 A 2-year retrospective survey done in northeastern Italy calculated an incidence of 14·7 cases per 100 000 children younger than 5 years.28 We report a high number of Kawasaki-like disease cases in the Bergamo province following the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic, with a monthly incidence that is at least 30 times greater than the monthly incidence of the previous 5 years, and has a clear starting point after the first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in our area. Group 2, diagnosed after SARS-CoV-2 appeared, showed evidence of seroconversion to the virus in the majority of patients.

In the past 20 years, viruses of the coronavirus family have been proposed as possibly implicated in the pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease. In 2005, a group from New Haven (CT, USA)29 identified a novel human coronavirus, designated New Haven coronavirus (HCoV-NH), in the respiratory secretions of eight of 11 children with Kawasaki disease versus one of 22 controls tested by RT-PCR. A serological test was not done. This report was followed by commentaries expressing a mixed sense of interest and scepticism.30 The arguments against this association were expressed by a group from Japan, who did a retrospective study31, 32, 33 on nasopharyngeal swab samples from 19 children with Kawasaki disease and 208 controls with respiratory tract infections, and found RNA sequences of HCoV-NH in five (2%) of 208 controls versus zero of 19 children with Kawasaki disease.

Another group from Japan explored the association between two different coronaviruses (HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E) and Kawasaki disease by serological tests. The immunofluorescence assay detected no difference in HCoV-NL63 antibody positivity between patients and controls, whereas HCoV-229E antibody positivity was higher in patients with Kawasaki disease.34 Given the pathogenesis of the disease, serology testing seems a more reliable tool than RT-PCR in detecting the cause of infection. This suggests that the coronavirus family might represent one of the triggers of Kawasaki disease, SARS-CoV-2 being a particularly virulent strain able to elicit a powerful immune response in the host.

In this study, the clinical and biochemical features of patients with Kawasaki disease diagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to differ from our historical cohort of patients; therefore, we have classified these patients as Kawasaki-like disease. From a clinical perspective, they were older, had respiratory and gastrointestinal involvement, meningeal signs, and signs of cardiovascular involvement. From a biochemical perspective, they had leucopenia with marked lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and increased ferritin, as well as markers of myocarditis. Similar clinical features are shared by patients with COVID-19.4 Additionally, these patients had a more severe disease course, with resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin and need of adjunctive steroids, biochemical evidence of MAS, and clinical signs in keeping with KDSS.

The proinflammatory effect of SARS-CoV-2 has been reported in adults with the most severe respiratory complications of COVID-19.35, 36 Many of these patients have a constellation of features classified under the term cytokine storm, such as fever, lymphopenia, elevated transaminases, lactate dehydrogenase, D-dimer, and ferritin, in keeping with MAS.11, 35, 37 Likewise, MAS is a form of cytokine storm, and might affect patients with Kawasaki disease.9, 15 All these elements supported the need to start adjunctive steroids. In our experience, this treatment is effective and safe, and should be considered by physicians treating patients with Kawasaki-like presentations in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Evidence of contact with the virus was confirmed by the presence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in eight of ten patients in group 2. It is possible that in the remaining two patients, who both had a negative serology, confounding factors played a role. One patient was tested just after an infusion of high-dose immunoglobulins. Additionally, qualitative antibody testing is reported to have a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 85–90% when compared with PCR test by nasal swab. It is also possible that this patient represents an usual presentation of Kawasaki disease outside of SARS-CoV-2 epidemic, as seen in previous years. Only two patients in group 2 presented a positive nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab sampling for SARS-CoV-2. This finding and the positivity of IgG antibodies suggest a late onset of the disease compared with the primary infection, due to the host immune response. This might be the reason why, in the past, no active viral infection could be shown in this disease. All these results and considerations support the hypothesis that the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 is responsible for a Kawasaki-like disease in susceptible patients.

We believe these findings have important implications for public health. The association between SARS-CoV-2 and Kawasaki-like disease should be taken into account when it comes to considering social reintegration policies for the paediatric population. However, the Kawasaki-like disease described here remains a rare condition, probably affecting no more than one in 1000 children exposed to SARS-CoV-2. This estimate is based on the limited data from the case series in this region.

This study has the limitations of a relatively small case series, requiring confirmation in larger groups. Genetic studies investigating the susceptibility of patients developing this disease to the triggering effect of SARS-CoV-2 should be done. Nonetheless, we reported a strong association between an outbreak of Kawasaki-like disease and the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the Bergamo province of Italy. Patients diagnosed with Kawasaki-like disease after the viral spreading revealed a severe course, including KDSS and MAS, and required adjunctive steroid treatment. A similar outbreak of Kawasaki-like disease is expected in countries affected by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Giulia Quattrocchi and Angela Amoroso for their help retrieving patients' data from filed notes.

Contributors

LV and LD'A made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work. LV and AM drafted the work. LV, AM, AG, LM, MR, MC, EB, and LD'A gave final approval for the Article to be published. LV, AM, AG, LM, MR, MC, EB, and LD'A agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AM, AG, LM, MR, MC, and EB acquired, analysed, or interpreted data for the Article. AG, LM, MR, MC, and EB revised the Article critically for important intellectual content. LD'A prepared the final draft and critically revised the Article for important intellectual content.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests and no financial support for this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Ministero della Salute Nuovo coronavirus: cosa c'è da sapere. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/

- 2.Flaxman S, Mishra S, Gandy A. Estimating the number of infections and the impact of nonpharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-13-europe-npi-impact/

- 3.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yonker LM, Shen K, Kinane TB. Lessons unfolding from pediatric cases of COVID-19 disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:1085–1086. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702. published online March 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicastro E, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, Di Giorgio A, D'Antiga L. A pediatric emergency department protocol to avoid intra-hospital dispersal of SARS-CoV-2 during the outbreak in Bergamo, Italy. J Pediatr. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.04.026. published online April 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, Liu Y, Li X, Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson LA, Canna SW, Schulert GS. On the alert for cytokine storm: immunopathology in COVID-19. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/art.41285. published online April 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Antiga L. Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients. The facts during the third epidemic. Liver Transpl. 2020 doi: 10.1002/lt.25756. published online March 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawasaki T, Kosaki F, Okawa S, Shigematsu I, Yanagawa H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MLNS) prevailing in Japan. Pediatrics. 1974;54:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato H, Sugimura T, Akagi T. Long-term consequences of Kawasaki disease. A 10- to 21-year follow-up study of 594 patients. Circulation. 1996;94:1379–1385. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanegaye JT, Wilder MS, Molkara D. Recognition of a Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e783–e789. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W, Gong F, Zhu W, Fu S, Zhang Q. Macrophage activation syndrome in Kawasaki disease: more common than we thought? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowley AH. Is Kawasaki disease an infectious disorder? Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:20–25. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e927–e999. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravelli A, Minoia F, Davì S. 2016 Classification criteria for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation Collaborative Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:481–489. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García-Pavón S, Yamazaki-Nakashimada MA, Báez M, Borjas-Aguilar KL, Murata C. Kawasaki disease complicated with macrophage activation syndrome: a systematic review. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:445–451. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi T, Saji T, Otani T. Efficacy of immunoglobulin plus prednisolone for prevention of coronary artery abnormalities in severe Kawasaki disease (RAISE study): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoints trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1613–1620. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61930-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shulman ST, Rowley AH. Kawasaki disease: insights into pathogenesis and approaches to treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:475–482. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura Y. Kawasaki disease: epidemiology and the lessons from it. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:16–19. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, Uehara R. Epidemiologic features of Kawasaki disease in Japan: results of the 2009-2010 nationwide survey. J Epidemiol. 2012;22:216–221. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yim D, Curtis N, Cheung M, Burgner D. Update on Kawasaki disease: epidemiology, aetiology and pathogenesis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:704–708. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makino N, Nakamura Y, Yashiro M. Descriptive epidemiology of Kawasaki disease in Japan, 2011–2012: from the results of the 22nd nationwide survey. J Epidemiol. 2015;25:239–245. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20140089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onouchi Y. The genetics of Kawasaki disease. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:26–30. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holman RC, Belay ED, Christensen KY, Folkema AM, Steiner CA, Schonberger LB. Hospitalizations for Kawasaki syndrome among children in the United States, 1997–2007. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:483–488. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181cf8705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marchesi A, Tarissi de Jacobis I, Rigante D. Kawasaki disease: guidelines of the Italian Society of Pediatrics, part I - definition, epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, clinical expression and management of the acute phase. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44:102. doi: 10.1186/s13052-018-0536-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Esper F, Shapiro ED, Weibel C, Ferguson D, Landry ML, Kahn JS. Association between a novel human coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:499–502. doi: 10.1086/428291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McIntosh K. Coronaviruses in the limelight. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:489–491. doi: 10.1086/428510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebihara T, Endo R, Ma X, Ishiguro N, Kikuta H. Lack of association between New Haven coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:351–352. doi: 10.1086/430797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esper F, Shapiro ED, Landry ML, Kahn JS. Reply to van der Hoek and Berkhout, Ebihara et al., and Belay et al. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:353. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turnier JL, Anderson MS, Heizer HR, Jone PN, Glodé MP, Dominguez SR. Concurrent respiratory viruses and Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e609–e614. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shirato K, Imada Y, Kawase M, Nakagaki K, Matsuyama S, Taguchi F. Possible involvement of infection with human coronavirus 229E, but not NL63, in Kawasaki disease. J Med Virol. 2014;86:2146–2153. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGonagle D, Sharif K, O'Regan A, Bridgewood C. The role of cytokines including interleukin-6 in COVID-19 induced pneumonia and macrophage activation syndrome-like disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102537. published online April 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molloy EJ, Bearer CF. COVID-19 in children and altered inflammatory responses. Pediatr Res. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-0881-y. published online April 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.