Abstract

Background:

Numerous studies have investigated the association between pretreatment serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but conclusions remain controversial. Thus, we performed a meta-analysis to assess systematically the relationship between ALP and prognosis in HCC.

Methods:

We searched the PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases for eligible studies up to October. A combined hazard ratio (HR) was determined to describe the correlation between pretreatment serum ALP level and prognosis in HCC patients. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of treatment either to the end point of the follow-up period or to the date of death by any cause. Disease-free survival (DFS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were defined as the period from the date of treatment to the date of last follow-up or to the date of recurrence. OS was regarded as the major outcome.

Results:

Altogether, 21 studies about OS and 6 studies about DFS/RFS were included in this meta-analysis. Our combined results showed that there was an inverse association of pretreatment serum ALP level with OS (HR=1.15, 95% CI: 1.12–1.19) and RFS (HR=1.78, 95% CI: 1.37–2.31).

Conclusion:

There was a close association between high pretreatment ALP level and poor survival in HCC patients, indicating that ALP may be used as a biomarker for prognosis. More high-quality studies are required to validate our findings further, considering the limitations of our meta-analysis.

Keywords: alkaline phosphatase, hepatocellular carcinoma, meta-analysis, prognosis

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks as the second most common cause of cancer-associated death in men and the sixth most common cause in women worldwide.[1] About 55% of all HCC cases occur in China,[2] but the incidence of HCC is increasing globally, especially in the United States and Europe.[3,4] HCC is an aggressive malignant tumor with fast infiltration growth, poor differentiation, and early metastasis.[5] Despite tremendous improvements in early diagnosis and therapeutic strategies, most patients with HCC still have unfavorable long-term outcomes.[6,7] Therefore, it is imperative to identify novel effective biomarkers for evaluating the prognosis of patients with HCC to guide individualized therapy.

Alkaline phosphatases (ALPs) belong to the metalloenzyme family, which can catalyze the hydrolysis of organic phosphate esters in an alkaline environment with low substrate specificity.[8] There are 4 genes encoding ALP: a tissue-nonspecific ALP gene located on 1p36.12 that is expressed in osteoblasts, hepatocytes, the kidneys, and the early placenta, and the 3 other tissue-specific ALP genes located on 2q37 and mainly expressed in the intestine, placenta, and germ cells.[9] Serum ALP level can be used to evaluate the burden and prognosis of bone diseases such as osteosarcoma and cancers with bone metastasis.[10] Additionally, increased serum ALP levels always occur in liver disease and may reflect liver injury.[11] A growing number of studies have suggested that higher pretreatment serum ALP level is associated with poorer survival of HCC patients, but other studies have found no relationship. This inconsistency may be due to limitations such as small sample sizes and individual study methodology. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis by combining relevant data from previous studies to assess systematically the correlation between pretreatment serum ALP levels and the survival of HCC patients.

1.1. Materials and methods

This meta-analysis was performed according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement issued in 2009.[12] This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gansu Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

1.2. Literature search strategy

We performed a comprehensive literature search in PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science up to October for eligible articles that assessed the association between pretreatment serum ALP levels and HCC patient survival. The searching terms included (“HCC” or “hepatocellular carcinoma” or “liver cancer” or “liver primary cancer” or “liver primary tumor” or “liver carcinoma”), and (“alkaline phosphatase”) and (“survival” or “prognosis” or “prognostic” or “outcome”). The search strategy was as following: ((((((((HCC[Title]) OR hepatocellular carcinoma[Title]) OR liver cancer[Title]) OR liver primary cancer[Title]) OR liver primary tumor[Title]) OR liver carcinoma[Title])) AND alkaline phosphatase[Title/Abstract]) AND ((((survival[Title/Abstract]) OR prognosis[Title/Abstract]) OR prognostic[Title/Abstract]) OR outcome[Title/Abstract]). Only articles published in English were considered for this meta-analysis.

1.3. Selection criteria

All potential articles were screened and selected by 2 independent authors. Studies satisfying the following criteria were included:

-

(1)

pathologically confirmed HCC;

-

(2)

reported the association of pretreatment serum ALP level with OS or DFS/RFS in HCC patients;

-

(3)

published in English; and

-

(4)

directly provided HRs with corresponding 95% CIs for prognosis or provided relevant information to estimate HRs with corresponding 95% CIs.

The exclusion criteria included:

-

(1)

reviews, letters, case reports, meeting abstracts, and meta-analyses;

-

(2)

papers focusing on other cancers;

-

(3)

studies enrolling HCC patients who had received anti-cancer therapy before testing baseline ALP level;

-

(4)

incomplete texts; and

-

(5)

studies with overlapping populations.

1.4. Data collection and quality assessment

Two investigators independently reviewed eligible articles and extracted data. The collected data included the name of the first author, publication year, patient origin, number of patients, age, disease stage, primary treatment type, cut-off value, and HRs with corresponding 95% CIs for overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and recurrence-free survival (RFS). OS was regarded as the major outcome, since most eligible studies reported OS. If HRs with corresponding 95% CIs calculated by univariate and multivariate analyses were both reported, the latter was chosen since it adjusted for the confounding factors with more accuracy. When HRs with corresponding 95% CIs were not reported directly, we calculated these values from Kaplan–Meier curves using Engauge Digitizer version 4.1 (http://digitizer.sourceforge.net), according to Tierney's method. The quality of eligible articles was evaluated by 2 investigators using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS). The scores of NOS range from 0 to 9 points. In this meta-analysis, we considered 6 or more points for high quality.

1.5. Statistical analysis

STATA version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) was used to perform the meta-analysis. Synthesized HRs with 95% CIs were used to describe the association between pretreatment ALP level and survival in HCC patients. HR > 1 and 95% CI not containing 1 suggested that high pretreatment ALP level was associated with worse survival in HCC. Cochran Q and Higgins I2 statistics were used to evaluate the heterogeneity across studies. We considered P < .05 and I2 > 50% to indicate significant heterogeneity. All studies included in our meta-analysis were observational in design, so it remains unlikely that these studies were conducted under the same exact conditions. Therefore, the random-effects model was used for the statistical analysis in this meta-analysis. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were performed to explore the sources of heterogeneity for OS by cut-off values for elevated ALP, primary treatment, mean age, and survival analysis type. Begg funnel plots and Egger linear regression tests were used to assess publication bias[13,14]; when the P value of Egger linear regression tests was below .05 or the Begg funnel plot was asymmetric, it meant significant publication bias existed. If publication bias was significant, the trim-and-fill method was used to estimate a corrected effect size after adjustment, which helped to determine whether the publication bias substantially affected the robustness of the pooled results.[15]

2. Results

2.1. Literature search and main characteristics of eligible studies

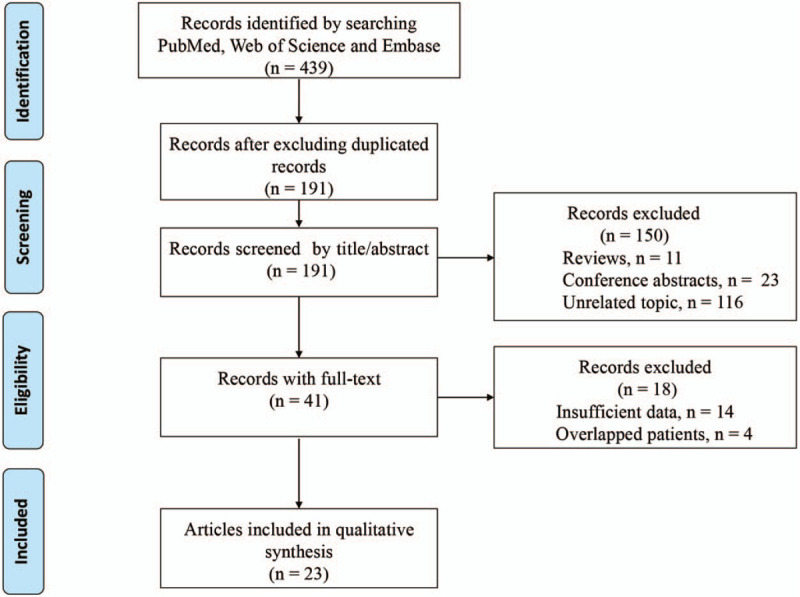

The initial search yielded 439 relevant records. Twenty-three articles encompassing 24 studies, involving 16,551 patients, were ultimately included in this meta-analysis.[16–38] The flow chart of the literature search and selection process is shown in Figure 1. Of the 24 included studies, 10 enrolled patients from China,[17,19,20,25,31,32,35–38] 4 from Japan,[21,24,28,30] 2 from the United States of America,[18,27] 2 from Spain,[26] 2 from Korea,[22,23] and 1 each from Germany,[29] Israel,[34] and France.[33] One additional study included patients from China, Romania, and the United States of America.[16] The cut-off value for high ALP level varied from 72.85 to 360 IU/L, though three studies did not report a cut-off value. With respect to HRs assessing the association between ALP and OS, most studies reported HRs generated from multivariate analyses; only 3 studies provided HRs generated from univariate analyses.[17,18,21] In total, 21 studies investigated the relationship between pretreatment serum ALP level and OS.[17–21,24–38] Six studies assessed the association between pretreatment serum ALP and DFS/RFS.[16,22,23,35–37] The main characteristics of eligible are summarized in Table 1. NOS scores for the included studies ranged from 6 to 8 (Table 1), indicating high quality across studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature selection process.

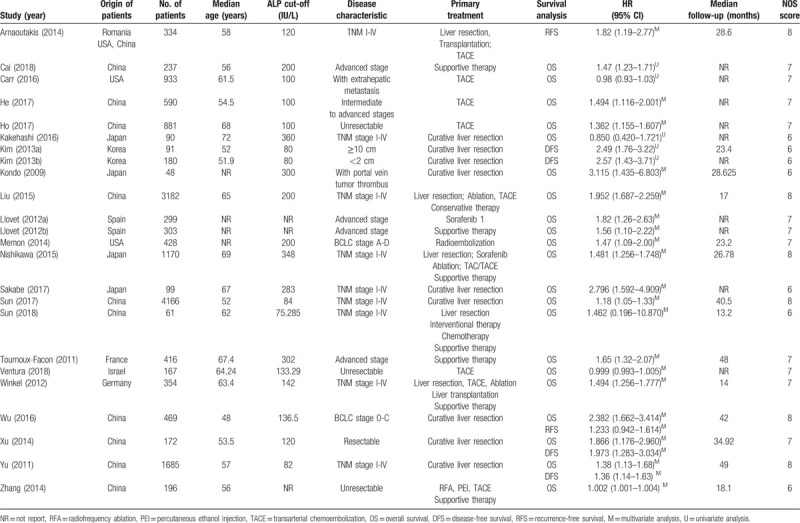

Table 1.

The main characteristics of the included studies in this meta-analysis.

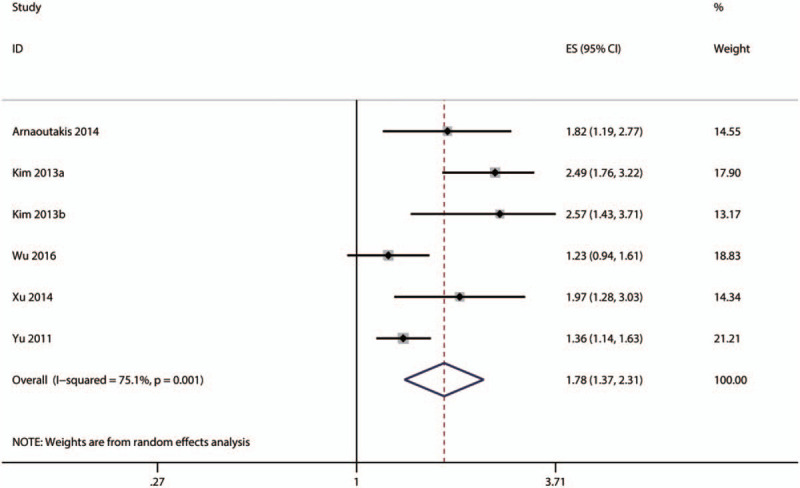

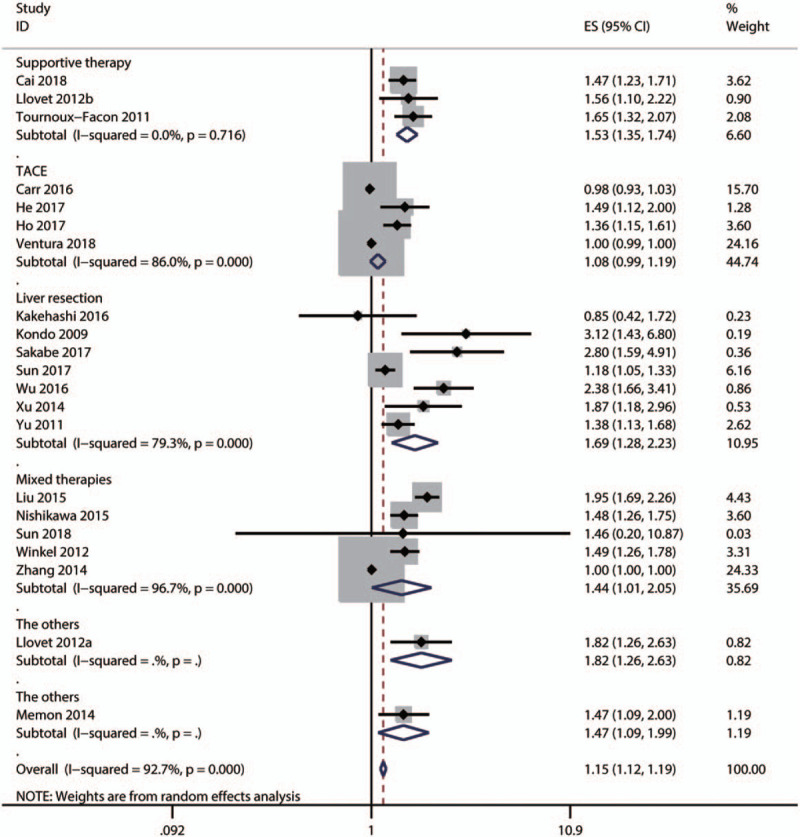

2.2. Association between pretreatment serum ALP level and prognosis in HCC patients

In total, 21 eligible studies provided data about the association between ALP and OS in HCC patients.[17–21,24–38] The pooled result showed that HCC patients with high serum ALP level had a significantly shorter OS (HR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.12–1.19) (Fig. 2). Six studies reported the association between serum ALP level and DFS/RFS.[16,22,23,35–37] Considering the similarity between DFS and RFS, we merged the 2 outcomes together for meta-analysis. As shown in Figure 3, higher pretreatment serum ALP level also significantly correlated with poorer DFS/RFS (HR = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.37–2.31).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the association between pretreatment serum alkaline phosphatase levels and overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of the association between serum ALP level and disease-free survival/recurrence-free survival (in HCC patients.

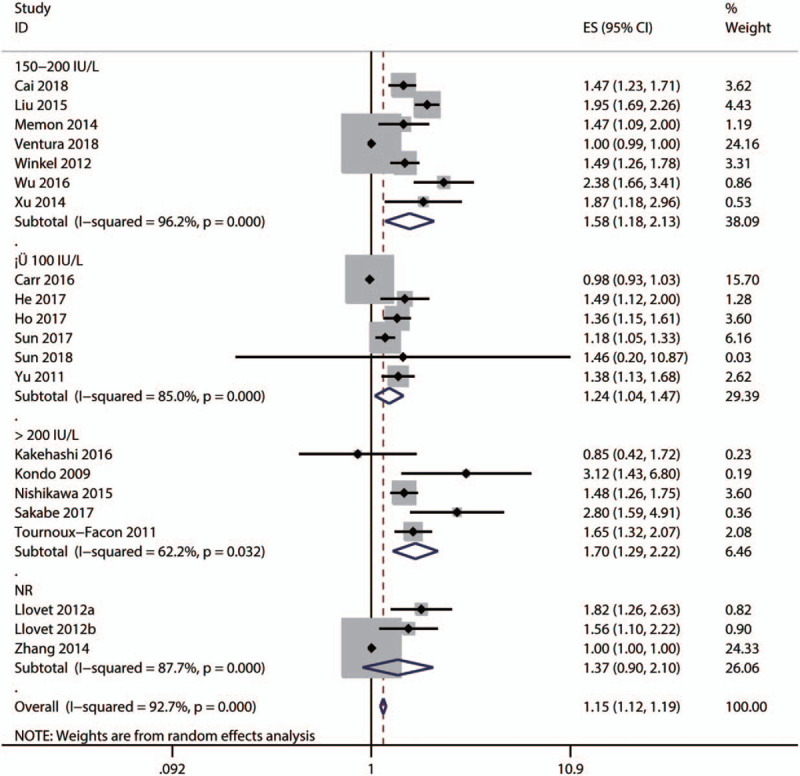

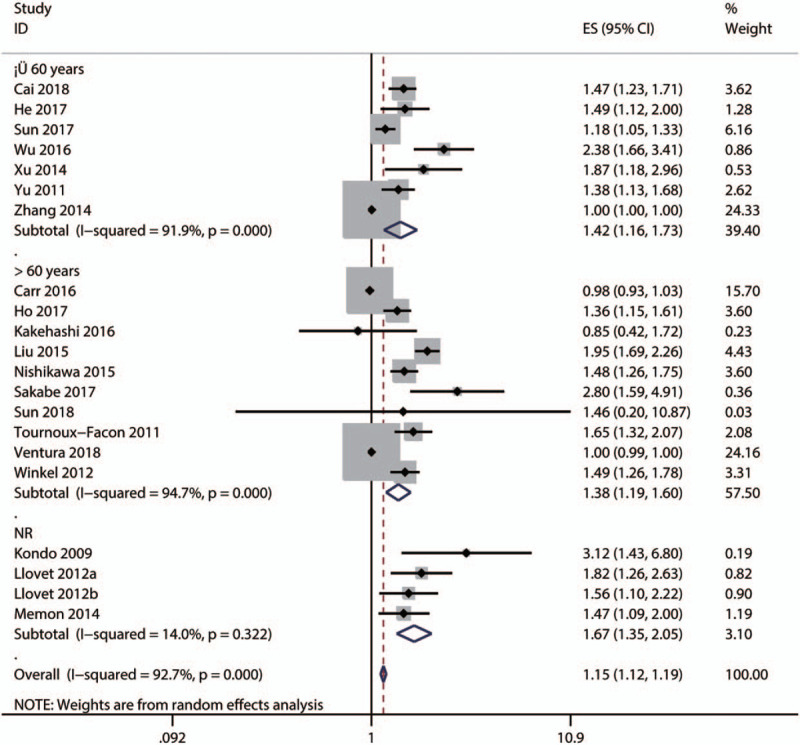

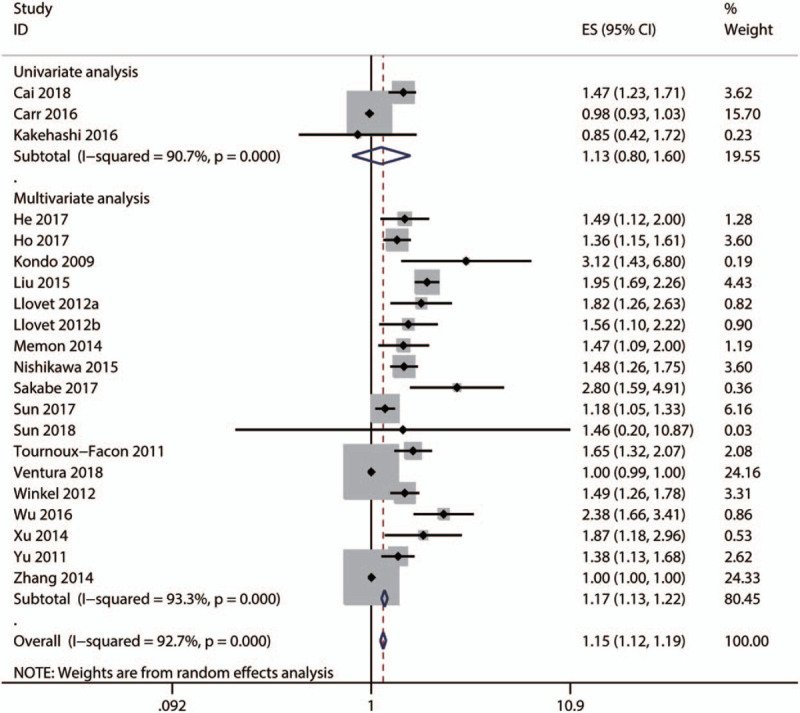

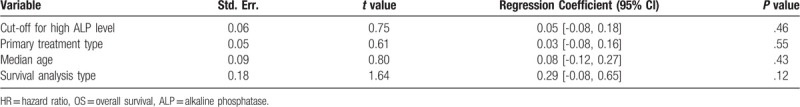

2.3. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses

Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were performed to explore the sources of heterogeneity OS by cut-off for high ALP level [≤100, 150–200, ≥200 IU/L, or not reported (NR)], primary treatment type [supportive, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), liver resection, mixed therapies, or others], median age (≤60, >60 years, or NR), and survival analysis type (univariate or multivariate analysis). The results showed that significant heterogeneity still existed in subgroups of cut-off for high ALP level (Fig. 4), primary treatment type (Fig. 5), median age (Fig. 6), and survival analysis type (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the meta-regression analyses showed that these factors did not explain the major heterogeneity in OS (Table 2). Overall, these results suggested that these factors might not be the contributors to the heterogeneity of OS. Although we failed to identify the sources of heterogeneity, these results showed that high serum ALP was closely associated with poor OS regardless of cut-off value (Fig. 4), median age (Fig. 5), primary treatment type (Fig. 6) and survival analysis type (Fig. 7), confirming the robustness of the pooled HR for OS. Due to the limited number of eligible studies about RFS/DFS, we did not perform a subgroup analysis for this outcome.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis by the cut-off for high alkaline phosphatase level for the pooled result of overall survival.

Figure 5.

Subgroup analysis by primary treatment type for the pooled result of overall survival.

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis by mean age for the pooled result of overall survival.

Figure 7.

Subgroup analysis by survival analysis type for the pooled result of OS, overall survival.

Table 2.

Meta-regression for exploring the source of heterogeneity of the pooled HR of OS.

2.4. Publication bias assessment

Egger and Begg tests were used to evaluate potential publication bias in studies of OS. The result showed that the Egger test P value was below .05 and the funnel plot was asymmetrical, suggesting that there was significant publication bias for OS (Fig. 8A). Next, we performed the trim-and-fill method to explore whether the publication bias influenced the stability and reliability of the pooled HR for OS. The trim-and-fill analysis showed that the corrected funnel plot was symmetrical (Fig. 8B) and the pooled HR was still above 1 with its CI not containing 1, indicating that our overall pooled HR for OS was robust and reliable. The Egger and Begg tests were not conducted for publication bias evaluation for RFS/DFS due to the limited number of eligible studies investigating these outcomes.

Figure 8.

Funnel plot of publication bias assessment for OS (A) and the adjusted funnel plots of publication bias assessment for OS (B). OS = overall survival.

3. Discussion

To date, the association between pretreatment serum ALP level and prognosis in HCC patients remains controversial. Therefore, this meta-analysis was conducted to assess comprehensively the correlation between pretreatment serum ALP level and prognosis in HCC patients. Our meta-analysis demonstrated that high pretreatment ALP level was significantly associated with poor OS (HR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.10–1.18) and RFS (HR=1.78, 95% CI: 1.37–2.31). Furthermore, our subgroup analysis and publication bias assessment verified that our overall pooled results were robust and reliable.

Several mechanisms may account for the association between serum ALP level and prognosis in HCC patients. First, cancer cells were found to exhibit higher ALP activity in the nucleolus and show a dynamic change in localization during cell cycles, indicating that ALP may facilitate tumor formation by modifying cell cycle regulation and cell proliferation.[35,36,39] Second, an increased ALP level has been observed in several non-malignant disorders associated with inflammation, such as hepatitis, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis.[36] Inflammation, as a hallmark of cancer, may contribute to cancer initiation and progression.[40] Hence, an increased serum ALP level may be linked to poor prognosis by reflecting more severe inflammation in HCC patients. Third, ALP is widely considered as a biomarker for tumor metastasis, especially bone metastasis[41]; it may be this underlying process that contributes to the bad outcome of HCC patients. Taken together, this body of evidence supports our findings in the current meta-analysis. Nevertheless, additional studies are needed to elucidate further the mechanisms underlying the association between serum ALP level and prognosis in HCC patients.

Several limitations of our meta-analysis are noted here. First, while significant heterogeneity existed in the current meta-analysis, we failed to identify the sources of heterogeneity through subgroup analyses. Furthermore, bias may have been introduced through the retrospective design of the included studies and through the exclusion of studies published in languages other than English. Additionally, as some studies did not directly report the HR for the association between ALP level and prognosis, we had to extrapolate the HR manually from survival curves and might have performed statistical errors in the process. The inconsistency in cut-off values for high ALP also was likely to cause statistical error, though our subgroup and meta-regression analyses indicated that this might not account for the significant heterogeneity found. As all included studies were observational in design, there may be numerous confounding factors contributing to the study heterogeneity and discounting the reliability of our statistical results. However, few factors were subjected to subgroup and meta-regression analyses due to limited data availability. Thus, it is possible that the influence of the inconsistency in ALP cut-off values may be masked by the other factors, or cannot be identified using the current statistical method, when the weight of its contribution to overall heterogeneity is relatively low. Additionally, the cut-off values for high ALP level among the included studies were not identical, which may limit the generalizability of our conclusions into clinical practice. Finally, because many study conditions were not consistent across our sample, and because we were unable to perform stratified analysis due to limited data, the generalizability of our results may be limited. Further homogeneous clinical studies are required to explore the association between serum ALP level and prognosis in HCC patients.

4. Conclusion

High pretreatment serum ALP level is closely correlated with poor survival in HCC patients and can be a potential biomarker for prognosis. Additional well-designed studies should be performed to validate our findings further.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Shihai Chen, Ping Sun.

Data curation: Shihai Chen.

Formal analysis: Shihai Chen.

Funding acquisition: Shihai Chen.

Methodology: Ping Sun, Yanlong Li.

Resources: Ping Sun, Yanlong Li.

Software: Shihai Chen, Ping Sun.

Supervision: Shihai Chen.

Validation: Shihai Chen, Yanlong Li.

Writing – original draft: Ping Sun.

Writing – review & editing: Shihai Chen, Yanlong Li.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALP = alkaline phosphatase, CI = confidence interval, DFS: disease-free survival, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, HR = hazard ratio, NOS = Newcastle-Ottawa scale, OS = overall survival, PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis, RFS: recurrence-free survival.

How to cite this article: Sun P, Chen S, Li Y. The association between pretreatment serum alkaline phosphatase and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Medicine. 2020;99:11(e19438).

This work was supported by grants from the Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Department Technical Research and Development Special Plan project (1105TCYA 020).

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- [1].Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yuen MF, Hou JL, Chutaputti A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;24:346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus(HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:175–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2012;379:1245–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lazarevich NL, Cheremnova OA, Varga EV, et al. Progression of HCC in mice is associated with a downregulation in the expression of hepatocyte nuclear factors. Hepatology 2004;39:1038–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liu Z, Tu K, Wang Y, et al. Hypoxia accelerates aggressiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma cells involving oxidative stress, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and non-canonical hedgehog signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;44:1856–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zheng J, Cai J, Li H, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio as prognostic predictors for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with various treatments: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;44:967–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kaplan MM. Alkaline phosphatase. N Engl J Med 1972;286:200–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Moss DW. Perspectives in alkaline phosphatase research. Clin Chem 1992;38:2486–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gu R, Sun Y. Does serum alkaline phosphatase level really indicate the prognosis in patients with osteosarcoma? A meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Ther 2018;14: Supplement: S468–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pratt DS, Kaplan MM. Evaluation of abnormal liver-enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1266–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fu YJ, Li KZ, Bai JH, et al. C-reactive protein/albumin ratio is a prognostic indicator in Asians with pancreatic cancers: a meta-analysis. Medicine 2019;98:e18219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liu X, Liu X, Qiao T, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of long non-coding RNA UCA1 in colorectal cancer: results from a meta-analysis. Medicine 2019;98:e18031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000;56:455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Arnaoutakis DJ, Mavros MN, Shen F, et al. Recurrence patterns and prognostic factors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic liver: a multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cai X, Chen Z, Chen J, et al. Albumin-to-alkaline phosphatase ratio as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients without receiving standard anti-cancer therapies. J Cancer 2018;9:189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Carr BI, Guerra V. Hepatocellular carcinoma extrahepatic metastasis in relation to tumor size and alkaline phosphatase levels. Oncology 2016;90:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].He CB, Lao XM, Lin XJ. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with recombinant human adenovirus type 5 H101 prolongs overall survival of patients with intermediate to advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a prognostic nomogram study. Chin J Cancer 2017;36:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ho SY, Liu PH, Hsu CY, et al. Prognostic role of noninvasive liver reserve markers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kakehashi A, Ishii N, Sugihara E, et al. CD44 variant 9 is a potential biomarker of tumor initiating cells predicting survival outcome in hepatitis C virus-positive patients with resected hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2016;107:609–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kim JM, Hyuck C, Kwon D, et al. Protein induced by vitamin K antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) is a reliable prognostic factor in small hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 2013;37:1371–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kim JM, Kwon CH, Joh JW, et al. The effect of alkaline phosphatase and intrahepatic metastases in large hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 2013;11:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kondo K, Chijiiwa K, Kai M, et al. Surgical strategy for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal vein tumor thrombus based on prognostic factors. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:1078–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu PH, Hsu CY, Hsia CY, et al. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of eleven staging systems. J Hepatol 2016;64:601–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Llovet JM, Pena CE, Lathia CD, et al. Plasma biomarkers as predictors of outcome in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:2290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Memon K, Kulik LM, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Comparative study of staging systems for hepatocellular carcinoma in 428 patients treated with radioembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014;25:1056–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nishikawa H, Kita R, Kimura T, et al. Hyponatremia in hepatocellular carcinoma complicating with cirrhosis. J Cancer 2015;6:482–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].op den Winkel M, Nagel D, Sappl J, et al. Prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Validation and ranking of established staging-systems in a large western HCC-cohort. PLoS One 2012;7:e45066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sakabe T, Azumi J, Umekita Y, et al. Expression of cancer stem cell-associated DKK1 mRNA serves as prognostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res 2017;37:4881–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sun HC, Xie L, Yang XR, et al. Shanghai score: a prognostic and adjuvant treatment-evaluating system constructed for Chinese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017;130:2650–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sun M, Zhang G, Guo J, et al. Prognostic value of pretreatment PET/CT lean body mass-corrected parameters in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Nucl Med Commun 2018;39:564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tournoux-Facon C, Paoletti X, Barbare JC, et al. Development and validation of a new prognostic score of death for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in palliative setting. J Hepatol 2011;54:108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ventura Y, Carr BI, Kori I, et al. Analysis of aggressiveness factors in hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:1641–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wu SJ, Lin YX, Ye H, et al. Prognostic value of alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and lactate dehydrogenase in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with liver resection. Int J Surg 2016;36:143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Xu XS, Wan Y, Song SD, et al. Model based on gamma-glutamyltransferase and alkaline phosphatase for hepatocellular carcinoma prognosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:10944–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yu MC, Chan KM, Lee CF, et al. Alkaline phosphatase: does it have a role in predicting hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence? J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15:1440–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhang JF, Shu ZJ, Xie CY, et al. Prognosis of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of seven staging systems (TNM, Okuda, BCLC, CLIP, CUPI, JIS, CIS) in a Chinese cohort. PLoS One 2014;9:e88182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Yamamoto K, Awogi T, Okuyama K, et al. Nuclear localization of alkaline phosphatase in cultured human cancer cells. Med Electron Microsc 2003;36:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, et al. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:e493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhao QT, Yang ZX, Yang L, et al. Diagnostic value of bone-specific alkaline phosphatase in lung carcinoma patients with bone metastases: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:17271–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]