Abstract

The study aimed to investigate the association between the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and thiazolidinediones use among type 2 diabetic patients who had risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma.

A population-based case-control study was performed using the database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program. The cases consisted of 23580 type 2 diabetic subjects aged 20 to 84 years with newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma between 2000 and 2011. The sex- and age-matched controls consisted of 23580 randomly selected type 2 diabetic subjects without hepatocellular carcinoma between 2000 and 2011. Ever use of thiazolidinediones was defined as subjects who had at least 1 prescription of thiazolidinediones before the index date. Never use of thiazolidinediones was defined as subjects who did not have a prescription of thiazolidinediones before the index date. The odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for the association between hepatocellular carcinoma and cumulative duration of thiazolidinediones use was measured by a multivariable logistic regression model.

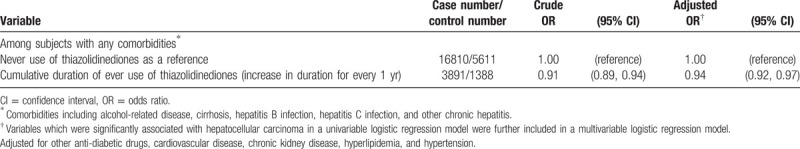

Among subjects with any 1 of the comorbidities including alcohol-related disease, cirrhosis, hepatitis B infection, hepatitis C infection, and other chronic hepatitis, a multivariable logistic regression model demonstrated that there was a negative association between hepatocellular carcinoma and every 1-year increase of cumulative duration of thiazolidinediones use (adjusted odds ratio 0.94, 95% confidence interval 0.92–0.97).

There was a negative association in a duration-dependent manner between the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and thiazolidinediones use among type 2 diabetic patients who had risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Keywords: case-control study, hepatocellular carcinoma, thiazolidinediones

1. Introduction

Thiazolidinediones are commonly used to treat patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.[1] Current evidence shows that insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) signaling is aberrantly regulated in numerous cancers.[2] Thiazolidinediones can appropriately regulate IGF-1 receptor signaling,[2,3] and therefore anti-cancer effects of thiazolidinediones are at least partially mediated by regulation of IGF-1 receptor signaling.[2] Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that thiazolidinediones use is associated with reduced risk of various cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer,[4–8] but a modestly increased risk of bladder cancer associated with pioglitazone use (a thiazolidinedione) was found.[9–11]

In Taiwan, hepatocellular carcinoma was the second leading cause of cancer-related death in 2018.[12] Hepatitis B infection, hepatitis C infection, heavy alcohol consumption and diabetes mellitus are significantly associated with increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan.[13–15] In the absence of these risk factors, it is less likely to develop hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. In view of previous studies only focusing on patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, we conducted a population-based case-control study to investigate whether there was an association between the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and thiazolidinediones use among type 2 diabetic patients who had risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

We performed a population-based case-control study using the database of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program. The insurance program was launched in March 1995 and the enrollment rate exceeded 99.7% of 23 million people living in Taiwan.[16,17] The details of the program have been recorded in previous studies.[18–20]

2.2. Selection of cases and controls

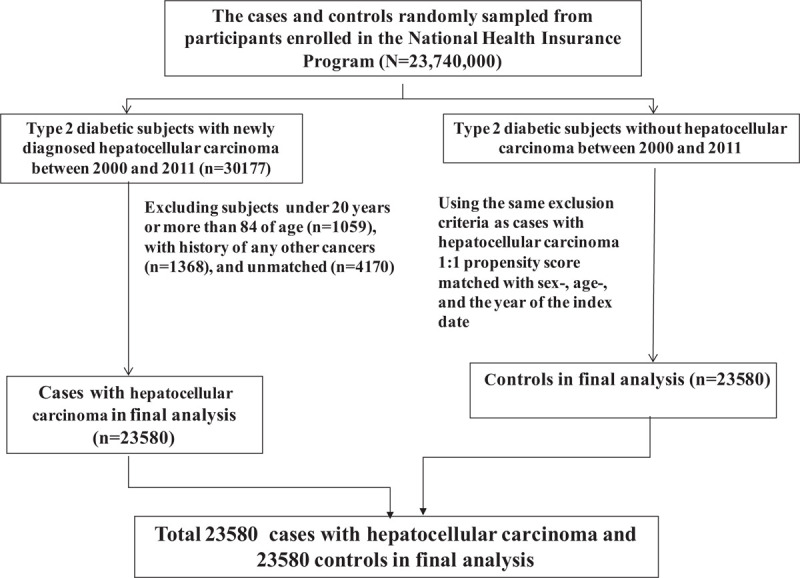

The cases consisted of type 2 diabetic subjects aged 20 to 84 years with newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma between 2000 and 2011 (based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, [ICD-9 codes] 155, 155.0, and 155.2). The date of a subject being diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma was defined as the index date. For each 1 case with hepatocellular carcinoma, 1 type 2 diabetic subject without hepatocellular carcinoma between 2000 and 2011was randomly selected as the control. The cases and controls were matched for sex, age (5-year interval), and the year of the index date. Subjects who had any other cancers (ICD-9 codes 140–208) before the index date were excluded from the study (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing selection of cases with hepatocellular carcinoma and controls.

2.3. Comorbidities

Comorbidities were selected as follows: alcohol-related disease, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, as well as chronic liver diseases including cirrhosis, hepatitis B infection, hepatitis C infection, and other chronic hepatitis. All comorbidities were diagnosed based on ICD-9 codes. The accuracy of ICD-9 codes has been evaluated in previous studies.[21–23]

2.4. Measurements of thiazolidinediones use and other anti-diabetic drugs use

Thiazolidinediones available in Taiwan between 2000 and 2011 were pioglitazone and rosiglitazone. Other anti-diabetic drugs available in Taiwan between 2000 and 2011 were listed as follows: metformin, sulfonylureas, α-glucosidase inhibitors, DPP-4 inhibitors, and insulins. Prescription histories of medications studied were collected. Ever use of medications was defined as subjects who had at least 1 prescription of medications studied before the index date. Never use of medications was defined as subjects who did not have a prescription of medications studied before the index date.[24–26]

2.5. Statistical analysis

We compared the distributions of sex, age group, thiazolidinediones use, other anti-diabetic drugs use, and comorbidities between the cases and the controls using the Chi-square test for categorized variables, and the t-test for continuous variables. The odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for the association between hepatocellular carcinoma and cumulative duration of thiazolidinediones use was measured by a multivariable logistic regression model. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina), and the results were considered statistically significant when 2-tailed P values were less than .05.

2.6. Ethical statement

Insurance reimbursement claims data used in this study were available for public access. Patient identification numbers were scrambled to ensure confidentiality. Patient informed consent was not required. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital in Taiwan (CMUH-104-REC2–115).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the study population

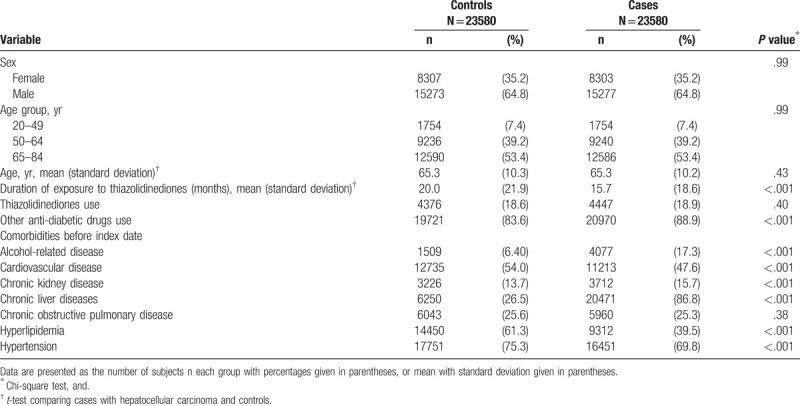

In Table 1, we identified 23580 type 2 diabetic cases with newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma and 23580 type 2 diabetic controls without hepatocellular carcinoma. The cases and controls had similar distributions of sex and age. The mean ages (standard deviation) were 65.3 (10.2) years in cases and 65.3 (10.3) years in controls, without statistical significance (t-test, P = .43). The mean durations (standard deviation) of thiazolidinediones use were 15.7 (18.6) months in cases and 20.0 (21.9) months in controls, with statistical significance (t-test, P < .001). The proportions of ever use of thiazolidinediones were 18.9% in cases and 18.6% in controls, without statistical significance (Chi-square test, P = .40). In addition, the proportions of ever use of other anti-diabetic drugs, alcohol-related disease, chronic kidney disease and chronic liver diseases were higher in the cases than the controls, with statistical significance (Chi-square test, P < .001 for all). Approximately 88% of cases with hepatocellular carcinoma (20701/23580) had an alcohol-related disease or/and chronic liver diseases (including cirrhosis, hepatitis B infection, hepatitis C infection, and other chronic hepatitis). These subjects were classified as high risk subjects.

Table 1.

Information between cases with hepatocellular carcinoma and controls.

3.2. Association between hepatocellular carcinoma and cumulative duration of thiazolidinediones use among high risk subjects

Among high risk subjects, a multivariable logistic regression model demonstrated that after adjustment for multiple variables, there was a negative association between hepatocellular carcinoma and every 1-year increase of cumulative duration of thiazolidinediones use (adjusted OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.92–0.97, Table 2).

Table 2.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval of association between hepatocellular carcinoma and cumulative duration of thiazolidinediones use among high risk subjects.

4. Discussion

Hepatitis B infection, hepatitis C infection, heavy alcohol consumption, and diabetes mellitus are well-known risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan.[13–15] In the absence of these risk factors, it is less likely to develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, the key point of our study was to focus on type 2 diabetic patients who had these established risk factors. Among these high risk patients, we observed that there was a negative association between hepatocellular carcinoma and every 1-year increase of cumulative duration of thiazolidinediones use (Table 2). This finding indicates that there is a duration-dependent effect of thiazolidinediones use on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Longer the duration of thiazolidinediones use, lower the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. One case-control study by Chang et al demonstrated that there was a negative association between the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and the cumulative dosage of thiazolidinediones use ≥120 DDD (defined daily dose).[5] Chang et al study demonstrated that there was a negative association between the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and the cumulative duration of thiazolidinediones use ≥3 years.[5] Chang et al study indicates that there were the dose-dependent and duration-dependent effects of thiazolidinediones on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. However, Chang et al study only focused on type 2 diabetic patients but without stratification of risk factors. Our study focused on type 2 diabetic patients who also had risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. It highlights that thiazolidinediones still have a protective effect on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among those patients who had at least 2 risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (diabetes mellitus and others).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Some strengths should be discussed. The whole population of Taiwan is well represented in a well recognized database with a large sample size and high participation rates in the National Health Insurance Program. We focused on patients who had risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma, including alcohol-related disease, cirrhosis, hepatitis B infection, hepatitis C infection, and other chronic hepatitis. We have adjusted for these established risk factors and therefore under-adjustment is less likely. The study design and results are more compatible with clinical needs.

Some limitations should be discussed. First, a causal-relationship cannot be determined by a case-control study. Second, due to the natural limitation of the database, the records of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and body mass index were not documented. Thus, we included alcohol-related disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as surrogate variables. This point was mentioned in previous studies.[27,28] Third, The study findings remain inconclusive, and should be interpreted more cautiously. More prospective cohort studies focusing on high risk populations are required to determine a causal-relationship.

5. Conclusion

There is a negative association in a duration-dependent manner between the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and thiazolidinediones use among type 2 diabetic patients who have risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. Due to study limitations, definitive conclusions for clinical practice cannot be drawn. Further methodologically well-constructed research is needed to clarify whether there is a causal relationship between thiazolidinediones use and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Author contributions

Shih-Wei Lai contributed to the conception of the article, initiated the draft of the article, and has approved the final draft submitted.

Cheng-Li Lin and Kuan-Fu Liao conducted data analysis.

Conceptualization: Shih-Wei Lai.

Formal analysis: Cheng-Li Lin, Kuan-Fu Liao.

Methodology: Shih-Wei Lai.

Supervision: Shih-Wei Lai.

Validation: Shih-Wei Lai.

Writing – original draft: Shih-Wei Lai.

Writing – review and editing: Shih-Wei Lai.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ICD-9 code = International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification.

How to cite this article: Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF. Association of hepatocellular carcinoma with thiazolidinediones use: a population-based case-control study. Medicine. 2020;99:17(e19833).

This study was supported in part by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan (MOHW109-TDU-B-212-114004), and China Medical University Hospital in Taiwan (DMR-107-192 and DMR-108-089), and MOST Clinical Trial Consortium for Stroke (MOST 108-2321-B-039-003). These funding agencies did not influence the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Ovalle F, Fernando OB. Thiazolidinediones: a review of their benefits and risks. South Med J 2002;95:1188–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mughal A, Kumar D, Vikram A. Effects of thiazolidinediones on metabolism and cancer: relative influence of PPARgamma and IGF-1 signaling. Eur J Pharmacol 2015;768:217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Higashi Y, Holder K, Delafontaine P. Thiazolidinediones up-regulate insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor via a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-independent pathway. J Biol Chem 2010;285:36361–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Monami M, Dicembrini I, Mannucci E. Thiazolidinediones and cancer: results of a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Acta Diabetol 2014;51:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chang CH, Lin JW, Wu LC, et al. Association of thiazolidinediones with liver cancer and colorectal cancer in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hepatology 2012;55:1462–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lin HC, Hsu YT, Kachingwe BH, et al. Dose effect of thiazolidinedione on cancer risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a six-year population-based cohort study. J Clin Pharm Ther 2014;39:354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Huang MY, Chung CH, Chang WK, et al. The role of thiazolidinediones in hepatocellular carcinoma risk reduction: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Am J Cancer Res 2017;7:1606–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen SW, Tsan YT, Chen JD, et al. Use of thiazolidinediones and the risk of colorectal cancer in patients with diabetes: a nationwide, population-based, case-control study. Diabetes Care 2013;36:369–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Turner RM, Kwok CS, Chen-Turner C, et al. Thiazolidinediones and associated risk of bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78:258–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bosetti C, Rosato V, Buniato D, et al. Cancer risk for patients using thiazolidinediones for type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Oncologist 2013;18:148–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Colmers IN, Bowker SL, Majumdar SR, et al. Use of thiazolidinediones and the risk of bladder cancer among people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012;184:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Ministry of Health and Welfare Taiwan. 2018 statistics of causes of death. Available at: http://www.mohw.gov.tw/EN/Ministry/Index.aspx. [cited on August 1, 2019, English version]. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang LY, You SL, Lu SN, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and habits of alcohol drinking, betel quid chewing and cigarette smoking: a cohort of 2416 HBsAg-seropositive and 9421 HBsAg-seronegative male residents in Taiwan. Cancer Causes Control 2003;14:241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lai SW, Chen PC, Liao KF, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in diabetic patients and risk reduction associated with anti-diabetic therapy: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen DS. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Hepatol Res 2007;37: Suppl 2: S101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Ministry of Health and Welfare Taiwan. 2018 Taiwan Health and Welfare Report. Available at: http://www.mohw.gov.tw. [cited on August 1, 2019, English version]. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liao KF, Huang PT, Lin CC, et al. Fluvastatin use and risk of acute pancreatitis:a population-based case-control study in Taiwan. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2017;7:24–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tsai TY, Lin CC, Peng CY, et al. The association between biliary tract inflammation and risk of digestive system cancers: a population-based cohort study. Medicine 2016;95:e4427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chen HY, Lin CL, Lai SW, et al. Association of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and acute angle-closure glaucoma. J Clin Psychiatry 2016;77:e692–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang IK, Lai SW, Lai HC, et al. Risk of and fatality from acute pancreatitis in long-term hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 2018;38:30–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shen ML, Liao KF, Tsai SM, et al. Herpes zoster correlates with pyogenic liver abscesses in Taiwan. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2016;6:24–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lin HF, Liao KF, Chang CM, et al. Correlation between proton pump inhibitors and risk of pyogenic liver abscess. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2017;73:1019–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liao KF, Cheng KC, Lin CL, et al. Etodolac and the risk of acute pancreatitis. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2017;7:25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lin HF, Liao KF, Chang CM, et al. Correlation of the tamoxifen use with the increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in elderly women with breast cancer: a case-control study. Medicine 2018;97:e12842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hung SC, Liao KF, Hung HC, et al. Tamoxifen use correlates with increased risk of hip fractures in older women with breast cancer: a case-control study in Taiwan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2019;19:56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liao KF, Chuang HY, Lai SW. Association between proton pump inhibitor use and Alzheimer's disease in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:1848–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF. Atrial fibrillation associated with acute pancreatitis: a retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2016;23:242–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF. Glaucoma may be a non-memory manifestation of Alzheimer's disease in older people. Int Psychogeriatr 2017;29:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]