Abstract

Rationale and objectives:

To evaluate the diagnostic performance of abbreviated screening breast magnetic resonance imaging (AB-MRI) for screening in women with previously treated breast cancer.

Materials and methods:

This retrospective study included consecutive AB-MRI from September 2015 to December 2016 in patients with previously treated breast cancer. Longitudinal medical record of patients’ demographics, outcomes of imaging surveillance and results of biopsy was reviewed. Protocol consisted of T2-weighted scanning and dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging including one pre-contrast and two post-contrast scans. A positive examination was defined as final assessment of BI-RADS 4 or 5 and negative was defined as BI-RADS 1, 2, or 3. Abnormal interpretation rate, cancer detection rate (CDR), sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were analyzed.

Results:

Among total 1043 AB-MRI, 29 (2.8%) AB-MRI had suspicious findings including 26 (2.5%) BI-RADS 4 and 3 (0.3%) BI-RADS 5 assessments. CDR was 9.59 per 1000. Performance outcomes were as follows: sensitivity, 71.4%; specificity, 98.2%; accuracy, 97.8%; PPV 1, 35.7%; PPV3 50%; and NPV 99.6%. Four cancers with false negative MRI were all early cancers of <1.0 cm with node negative. One was palpable interval cancer while the others were alternative screening modality-detected asymptomatic cancers before the next MRI screening.

Conclusion:

AB-MRI showed high accuracy and NPV for detecting cancer recurrence in women with previously treated breast cancer. Missed cancers were all minimal cancers with node negative.

Keywords: abbreviated breast MRI, AB-MRI, diagnostic performance, screening

1. Introduction

The role of breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a screening tool has been well established.[1–4] In 2007, the American Cancer Society guidelines highly recommended MRI screening for high-risk groups with greater than 20% to 25% lifetime risk-based on assessment including a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer and who were treated for Hodgkin disease.[5] Recently many studies have reported that supplemental screening with breast MRI is also very valuable for women with previously treated for breast cancer due to its high diagnostic performance and acceptable positive biopsy results.[6–12] In 2018, the American Cancer Society guideline included women with personal history of breast cancer and dense tissue or those diagnosed by age 50 in the screening MRI recommendation.[13] However, widespread use of screening MRI has been limited in practice due to its high cost and time needed to acquire and interpret the examinations. High false positive rate and low specificity were additional problems of screening MRI.[3,9]

To overcome these limitations, abbreviated breast protocol (ABP) for screening MRI has been introduced. It can substantially reduce the acquisition time to 10 to 15 min compared to 30 to 40 min of conventional full diagnostic protocol (FDP). In addition, its reading time is 30 s to 3 min compared to 3 to 9 min of FDP.[14–19] Preliminary data reported by Kuhl et al[14] demonstrated that the sensitivity and specificity of abbreviated breast MRI (AB-MRI) were comparable to those of conventional FDP. Many recently published studies have focused on the diagnostic performance of AB-MRI compared to FDP.[16,17,19–24] However, these studies analyzed the performance of ABP after creating AB-MRI via selection of specific sequences derived from FDP. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no study focusing on the diagnostic performance of AB-MRI alone in real clinical practice of screening.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of AB-MRI for the surveillance of women with previously treated breast cancer, focusing on the diagnostic performance and limitation of AB-MRI.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ethics Committee and informed consent was waived.

We retrospectively reviewed the radiologic reports and clinical data of 1159 consecutive screening breast MRI in 1043 patients, performed between September 2015 and December 2016. All patients had personal history of breast cancer surgery. All screening breast MRI was acquired using abbreviated breast MRI protocol, for we started to apply the abbreviated protocol to screening breast MRI since September 2015 in our hospital. Among them, we excluded 116 cases that did not have at least 1-year follow up images or histological confirmation. Finally, 1043 AB-MRI examinations performed in 973 patients with previously treated breast cancer were included in our study. In our institution, annual mammography with bilateral whole breast US was performed as a routine follow up protocol in all patients for postoperative surveillance after breast cancer surgery. Screening MRI was recommended in the patients of premenopausal state with dense breasts and age ≤50, and conducted between the routine mammographic follow up. The sequence of postoperative surveillance is mammography with US, screening MRI, next mammography with US, and next screening MRI, alternatively per every 6 months for about 5 years.

2.2. Breast MRI acquisition

The postoperative AB-MRIs were performed using 1.5-T Achieva scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) and 3.0-T Achieva scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) using dedicated bilateral phased-array breast coil, with patient in prone position.

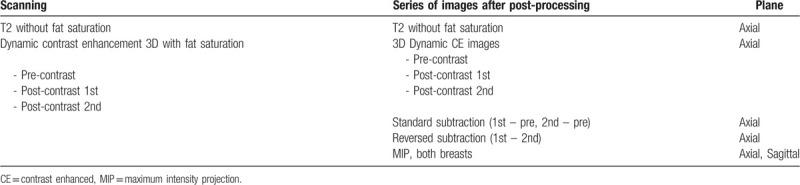

The protocol of AB-MRI for scanning and imaging after post-processing is shown in Table 1. The MRI protocol consisted of axial turbo spin-echo T2-weighted imaging and axial 3-dimensional dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) imaging of pre-contrast and two post-contrast sequences with fat suppression. A 0.1-mmol/kg bolus injection of gadobutrol (Gadovist; Bayer Healthcare, Berlin, Germany) was carried out via an antecubital vein, followed by a 20-mL saline flush. Two post-contrast enhanced images were obtained from 30 s after contrast injection and the acquisition time for one scanning was about 60 s (post-contrast 1 and 2 min images). The DCE-MRI parameters on 1.5-T scanner were as follows: repetition time/echo time (ms), 6.5/2.5; 1.5 mm sections without gap; flip angle, 12°; matrix size, 376 × 374; and field of view, 32 × 32 cm. Images with the 3.0-T scanner were obtained using the following parameters: repetition time/echo time (ms), 4.6/2.3; 1.5 mm sections with no gap; flip angle, 24°; matrix size, 512 × 512; and field of view, 32 × 32 cm. After image acquisition, standard subtraction images (pre-contrast images were subtracted from the early post-contrast images) and reversed subtraction images (the second post-contrast images were subtracted from the first post-contrast images) were obtained automatically on a pixel-by-pixel basis. Additionally, bilateral axial and sagittal maximum-intensity projection images were processed. Total scan time ranged from 10 to 11 min.

Table 1.

Abbreviated protocol of screening breast MRI.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

We retrospectively reviewed the original MRI reports which had been made by one of five breast radiologists according to Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS). The presence of early washout kinetics was assessed based on two post-contrast enhanced images. The reports included not only in-breast lesions but also lymph nodes in internal mammary chain and covered axillary area. At the time of MRI reporting, radiologists had the information that the previous mammography and US performed in 6 months earlier had no suspicious lesion.

A positive examination result was defined as BI-RADS category of 4 or 5 while a negative result was defined as BI-RADS category of 1, 2, or 3. Pathologic confirmation was recommended for those who had positive results. BI-RADS category 3 lesions were usually managed with a 6 month follow-up MRI.

Medical records were reviewed including patient age, characteristics of primary cancer including tumor type and stage, interval between the operation and MRI examination, results of following mammography and breast US, and results of breast biopsy or surgery after screening breast MRI.

Reference standard was defined as a combination of results of 12-month follow-up images including mammogram, breast US, or MRI and/or pathology. Histological result and guidance modality of biopsy were also reviewed in the cases of biopsy. If the biopsy result was malignant, histologic type, size, nuclear grade, tumor receptor status, and axillary nodal status of the lesion were reviewed after surgery.

We evaluated outcomes of screening AB-MRI including abnormal interpretation rate, cancer detection rate (CDR), sensitivity, and specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). Abnormal interpretation rate was defined as the number of positive examinations out of total examinations. PPV1 was defined as number of cancers in positive examinations. PPV3 was defined as number of known biopsies done that resulted in a cancer diagnosis. False negative screening MRI was defined as the negative result of screening MRI followed by a histologically proven breast cancer within 12 months. Interval cancer was defined as a breast cancer diagnosed after a negative MRI examination result because of clinical symptoms before the next scheduled screening MRI examination. Confidence intervals are shown at 95%.

3. Results

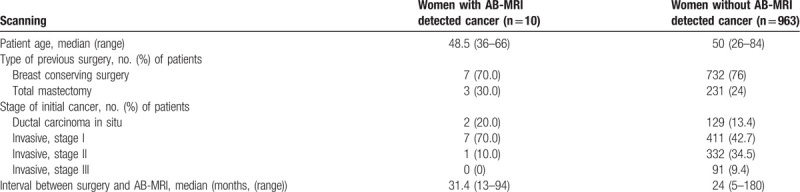

A total of 1043 AB-MRI examinations were performed for 973 women with a median age of 50 years (range 26–84 years) during the study period. Among them, 768 (73.6%) examinations were initial postoperative screening MRI and 275 (−26.4%) were subsequent postoperative screening MRI. Stages of initial cancer were as follows: stage 0 in 131 women, stage I in 418 women, stage II in 333 women, and stage III in 91 women. Type of previous breast surgery was breast conservation surgery in 739 (76.0%) women, mastectomy in 230 (23.6%) women, and both breast conservation surgery and mastectomy for bilateral breast cancers in 4 (0.4%) women. Median interval between surgery and AB-MRI was 24 months (range 5–180 months). The characteristics of women with AB-MRI detected cancer and women without AB-MRI detected cancer are compared in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 973 women with a history of breast cancer surgery who underwent screening with abbreviated breast MRI (AB-MRI).

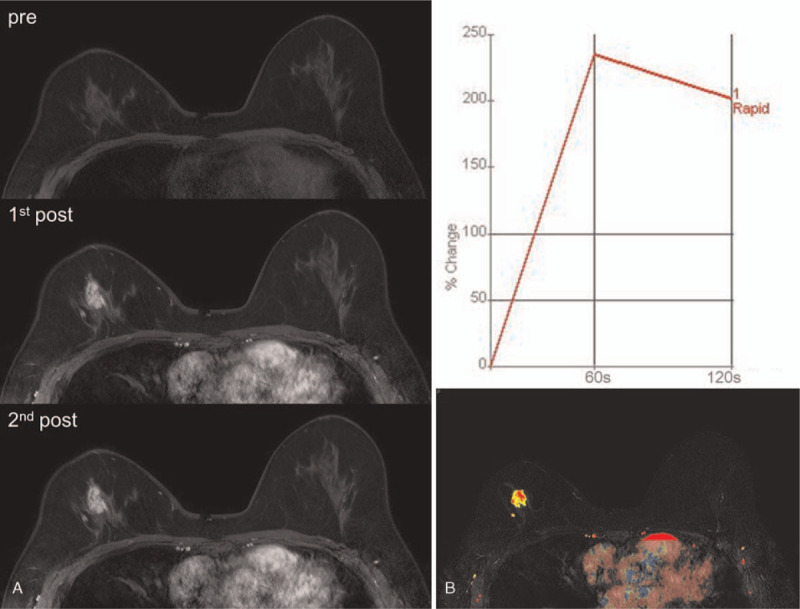

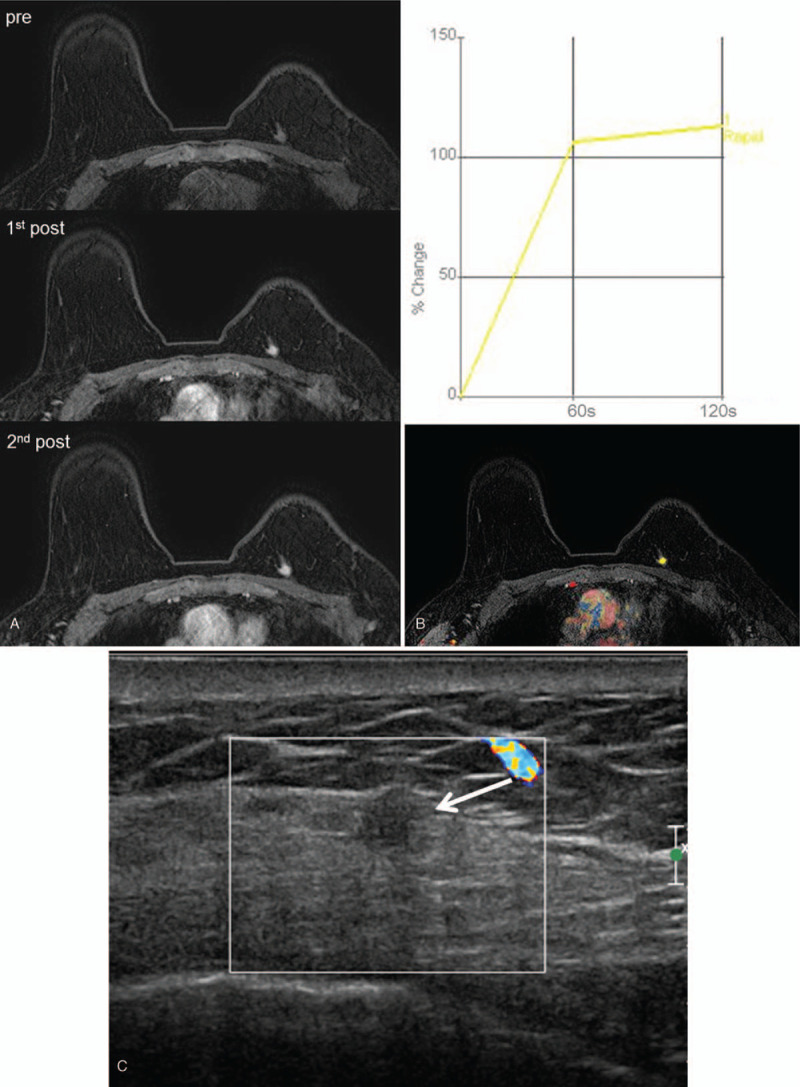

The final assessment category was distributed as follows: BI-RADS category 1 for 768 examinations (73.6%), BI-RADS category 2 for 189 examinations (18.1%), BI-RADS category 3 for 55 examinations (5.3%), BI-RADS category 4 for 26 examinations (2.5%) and BI-RADS 5 (0.3%) for examinations. Overall, 29 (2.8%) of 1043 examinations received abnormal interpretation, including 24 in-breast lesions and five abnormal lymph nodes. All three BI-RADS 5 lesions were confirmed to be malignant (ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS], n = 2; invasive ductal carcinoma [IDC], n = 1) by core needle biopsy (Fig. 1). Of the 26 BI-RADS 4 lesions, 17 cases were confirmed histologically to be malignant (n = 7) or benign (n = 10) lesions. Ten cases with benign biopsy results showed no evidence of malignancy on follow up images for more than 1 year (Fig. 2). Nine cases showed corresponding typically benign findings on following targeted US and mammogram for MR-detected lesion, and final assessments after integration of MRI, targeted US and mammogram were downgraded to BI-RADS 2 or 3. They underwent follow up imaging surveillance for more than 1 year and showed negative results. Of 55 BI-RADS 3 lesions, 32 had followed MRI after 6 months while the others were followed up with mammography and/or US. After 1-year follow up, 41 lesions were downgraded to category 1 or 2 while three lesions were upgraded to category 4 and underwent biopsies (1 IDC, 1 intraductal papilloma, and 1 foreign body reaction). BI-RADS 1 or 2 results (n = 957) were followed up by routine screening protocol, and three of them were turned out to be malignant within 12 months after negative screening MRI. Management following results of screening MRI and clinical or histological results are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1.

A 39-year-old-woman, who had right breast conserving surgery for invasive ductal carcinoma (T1N0) 2 years ago, underwent post-operative screening MRI. Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) images consisted of pre-contrast, and two post-contrast sequences demonstrated an irregular mass of 2 cm in size in right upper center breast (A). CAD color overlay map of the mass showed washout kinetic pattern (B). The mass was assessed as breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) 5. Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy revealed ductal carcinoma in situ.

Figure 2.

A 58-year-old-woman, who had left breast conserving surgery for invasive ductal carcinoma (T1N0) 1 year ago, underwent post-operative screening MRI. An irregular mass of 0.8 cm in size was found in the periphery of left upper inner quadrant, upper side of operation scar (A). CAD color overlay map displayed plateau kinetic pattern (B). The mass was assessed as breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) 4. Targeted ultrasound with Doppler study for that lesion (C) showed 0.7 cm size irregular isoechoic mass (arrow) with no vascularity. Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy revealed fat necrosis.

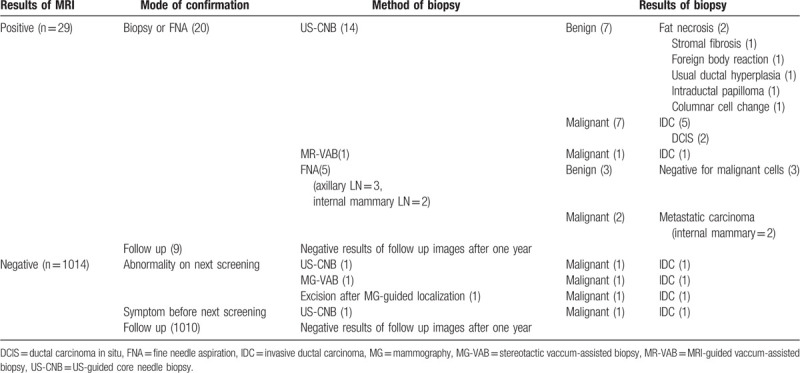

Table 3.

Outcomes of screening AB-MRI.

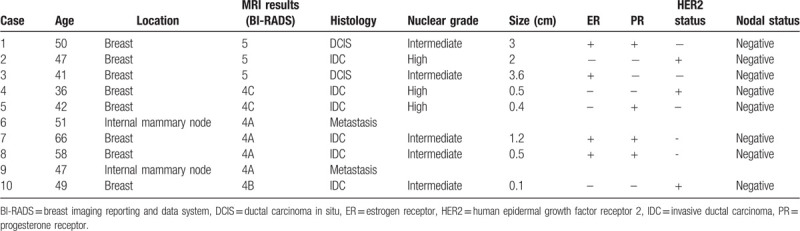

CDR was 9.59 per 1000 (10 of 1043). Of the 10 screening MRI-detected cancers, 5 (50%) were diagnosed in the ipsilateral breasts of previous treated breast cancers, 3 (30%) were in the contralateral breasts and 2 (20%) were lymph node metastases in the ipsilateral internal mammary area. All cancers were in stage 0 or 1. The median size of six invasive carcinomas was 0.5 cm (Table 4).

Table 4.

Demographics of MRI-detected cancers.

Overall, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of AB-MRI were 71.4% (95% CI, 41.9–91.6%), 98.2% (95% CI, 97.1–98.9%), and 97.8% (95% CI, 96.7–98.6%), respectively. PPV 1 was 35.7% (10 malignancies in 29 positive examinations) and PPV3 was 50% (10 malignancies in 20 biopsies performed). NPV was 99.6% (95% CI, 99.1–99.8%).

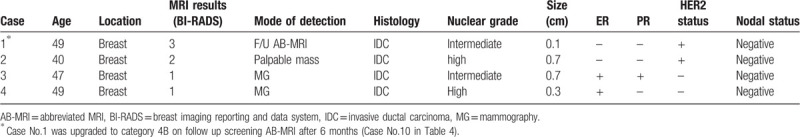

Four cancers with false negative MRI were all minimal cancers of less than 1.0 cm in size with node negative status (Table 5). Only one cancer was interval cancer detected as a symptomatic palpable mass at 7 months after screening MRI. The results of routine screening mammography and US performed 6 months after MRI were also negative. Two cancers were detected by alternative mammographic screening at 6 months after screening MRI (Fig. 3), and the last one IDC was detected by screening MRI but categorized as BI-RADS 3 on initial screening MRI. On the 6 months follow up MRI, it was upgraded into category 4B.

Table 5.

Demographics of false negative cancers.

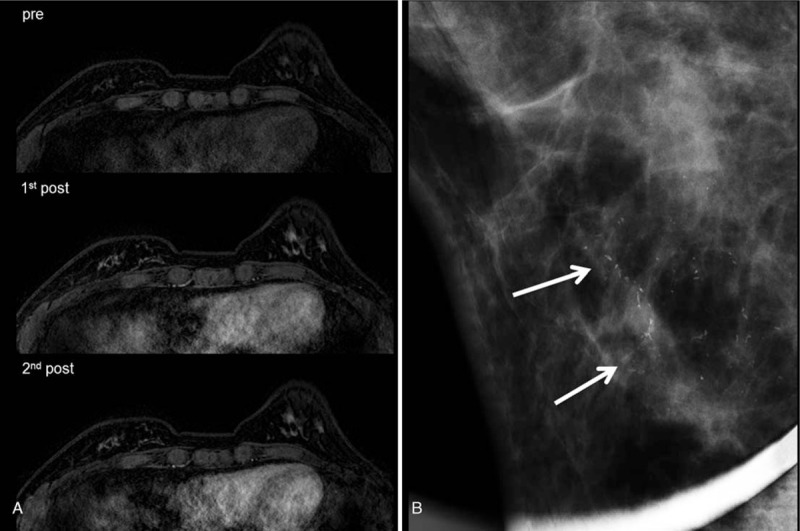

Figure 3.

A 47-year-old woman, who had right breast conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ 1 year ago, underwent post-operative screening MRI. Dynamic contrast-enhanced images (A) demonstrated no suspicious finding. Alternative 6 months follow up mammogram (B) revealed new fine linear calcifications inferior side of postoperative scar in right lower breast (arrows). Stereotactic vaccum-assisted biopsy of this lesion showed recurrent invasive ductal carcinoma with ductal carcinoma in situ.

Of the 19 false positive cases, three lesions were enlarged benign lymph nodes in ipsilateral (n = 2) and contralateral (n = 1) axillae. Among 16 breast lesions, nine cases were ipsilateral and 6 were contralateral lesions. Five of nine ipsilateral lesions were new findings near the operation sites. Only one (6.3%) of 16 of false positive benign breast lesions showed washout kinetics, while six (75%) of 8 recurrent breast cancers showed early washout kinetics based on two post-contrast images (Fig. 1).

4. Discussion

After introduction of AB-MRI using limited sequences, many recent studies have reported that AB-MRI could be used in clinical practice, mainly for screening purpose.[14–17,19–24] Compared with FDP, ABP for screening MRI showed no statistically significant differences, with sensitivity of 82% to 100% and specificity of 45% to 97%. Cancer detection rate was 13.3 per 1000 women in high risk screening group.[23] While all previous studies were reader studies with selected specific sequences derived from FDP, Choi et al[25] investigated the diagnostic performance of AB-MRI in postoperative screening group with scanning ABP only. They detected 12 malignancies out of 799 examinations (15 per 1000 women) with sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 89.2%. PPV1 and PPV3 were 12.4% and 61.5%, respectively. However, they conducted mammography, US, and MRI at the same time, and interpreted AB-MRI in integration of mammographic and US findings. Therefore, the diagnostic performance was not achieved by AB-MRI only, but by a combination of mammography, US and AB-MRI screening.

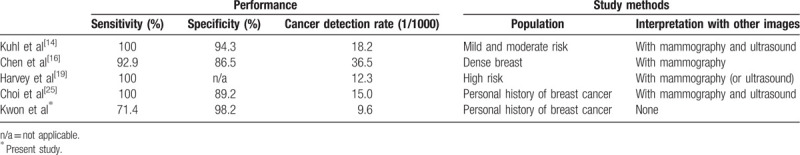

In our study, 1043 postoperative screening AB-MRI examinations detected 10 malignancies (9.59 cancers per 1000 women). Although the specificity, PPV, and diagnostic accuracy were very high, our results showed lower sensitivity and CDR compared to the study of Choi et al.[25] Because we performed AB-MRI alone without mammography or US, our results represented diagnostic performance of AB-MRI only. This might be the cause of differences in sensitivity and CDR between our study and the study of Choi et al.[25] We listed the performance of screening AB-MRI and the difference of study methods of previous studies compared with ours in Table 6.

Table 6.

The performance and study methods of published studies on Abbreviated protocol of screening breast MRI.

We initially expected that some cancers that showed abnormalities only on mammography or US without definite early enhancement on AB-MRI would be more likely to be in situ carcinoma or lower grade invasive cancers than MRI-detected cancers. However, there was no difference in size, histologic type, nuclear grade, tumor receptor status, or initial stage between AB-MRI detected cancers and cancers missed by AB-MRI. The small number of overall recurrences and small number of false negative MRI might have influenced the results to show no difference. All four cancers with false negative MRI were minimal cancers (mean size, 0.45 cm) in stage 1 (T1N0) and only one of them was interval cancer.

Most of previous studies[14–16,18,19,21,22] included only one post-contrast scanning in AB-MRI protocol except one study.[20] To overcome inability to generate time–intensity curve, we acquired two post-contrast enhanced images at 60 and 120 s, and obtained enhancement kinetics from them. Even kinetic analysis is limited, it could be helpful in cases of lesions showing early washout within 120 s. In our study, recurrent breast cancers showed higher rate of early washout kinetics than false positive breast lesions (75% vs 6%). Therefore, short kinetic curves calculated from two early post-contrast scans might be helpful for differentiating malignancy from benign lesions. However, our results were derived from only 29 cases with positive MRI results, therefore further studies with larger number of positive cases are needed to prove the usefulness of kinetic curve from two early post-contrast scanning.

Although there is no published guideline of medical audit for screening MRI, several reports have focused on the diagnostic performance of screening MRI with FDP in women with previously treated breast cancer.[6–12] They demonstrated high sensitivity of 80.0% to 100%, specificity of 82.2% to 95.3%, PPV1 of 4.4% to 13.3%, and PPV3 of 17.9% to 43.5%. The CDR had a relatively wide range (7.3–118.1 per 1000 women). Our results with AB-MRI showed comparable CDR, higher specificity and PPV, but slightly lower sensitivity than the previous reports with FDP MRI.[6–12] However, there was a difference in the method of study that three of four (75%) false negative cases in our study were detected before next screening MRI not because of their symptom but detected by other screening modality such as mammographic calcifications.6 months after AB-MRI screening. This alternative pair of screening protocol in our institution using annual AB-MRI and annual mammography combined with US with 6 months interval, exaggerated the false negative AB-MRI than it really was.

Our study has some limitations. First, it was a retrospective study from a single institution with small number of recurrence cases. We did not perform screening AB-MRI in all women with previously treated breast cancer. In our institution, postoperative screening MRI is ordered by the oncologist or surgeon, and is usually recommended for the women in premenopausal state and those with dense breasts. Therefore, the results might be different in other population of screening breast MRI. Second, we investigated outcomes of MRI results based on retrospective review of radiologic reports and clinical records without reviewing all MRI images. Third, for auditing AB-MRI, we validated diagnosis with follow-up imaging surveillance and medical records after 1 year based on the previous publications.[9–12] However, not all patients were followed up with screening MRI and many cases with BI-RADS 1 or 2 screening MRI results had only follow-up mammography and US.

In conclusion, AB-MRI showed high specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy with acceptable sensitivity for detecting breast cancer recurrence in women with previously treated breast cancer. Missed lesions were all minimal breast cancers with negative lymph node. Therefore, AB-MRI can be considered as an alternative to FDP MRI in postoperative surveillance with decreased examination time.

Author contributions

Clinical Study: Boo-Kyung Han, Eun Sook Ko, Ji Soo Choi.

Manuscript editing: Ji Soo Choi, Eun Young Ko.

Manuscript writing: Mi-ri Kwon.

Methodology: Eun Young Ko.

Reference search and statistical support: Ko Woon Park.

Supervision: Eun Young Ko.

Mi-ri Kwon orcid: 0000-0001-8225-3690.

Eun Young Ko orcid: 0000-0001-6679-9650.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AB-MRI = abbreviated breast MRI, ABP = abbreviated breast protocol, BI-RADS = Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System, CDR = cancer detection rate, DCE = dynamic contrast-enhanced, DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ, FDP = full diagnostic protocol, IDC = invasive ductal carcinoma, MIP = maximum-intensity projection, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, NPV = negative predictive value, PPV = positive predictive value, US = ultrasound.

How to cite this article: Kwon Mr, Ko EY, Han BK, Ko ES, Choi JS, Park KW. Diagnostic performance of abbreviated breast MRI for screening of women with previously treated breast cancer. Medicine. 2020;99:16(e19676).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors have no funding information to disclose.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Kuhl CK, Schmutzler RK, Leutner CC, et al. Breast MR imaging screening in 192 women proved or suspected to be carriers of a breast cancer susceptibility gene: preliminary results. Radiology 2000;215:267–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lehman CD, Isaacs C, Schnall MD, et al. Cancer yield of mammography, MR, and US in high-risk women: prospective multi-institution breast cancer screening study. Radiology 2007;244:381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA 2012;307:1394–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Evans DG, Kesavan N, Lim Y, et al. MRI breast screening in high-risk women: cancer detection and survival analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;145:663–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin 2007;57:75–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brennan S, Liberman L, Dershaw DD, et al. Breast MRI screening of women with a personal history of breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:510–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Schacht DV, Yamaguchi K, Lai J, et al. Importance of a personal history of breast cancer as a risk factor for the development of subsequent breast cancer: results from screening breast MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014;202:289–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Giess CS, Poole PS, Chikarmane SA, et al. Screening breast MRI in patients previously treated for breast cancer: diagnostic yield for cancer and abnormal interpretation rate. Acad Radiol 2015;22:1331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cho N, Han W, Han BK, et al. Breast cancer screening with mammography plus ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging in women 50 years or younger at diagnosis and treated with breast conservation therapy. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1495–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gweon HM, Cho N, Han W, et al. Breast MR imaging screening in women with a history of breast conservation therapy. Radiology 2014;272:366–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Weinstock C, Campassi C, Goloubeva O, et al. Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) surveillance in breast cancer survivors. Springerplus 2015;4:459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lehman CD, Lee JM, DeMartini WB, et al. Screening MRI in women with a personal history of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108:djv349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Monticciolo DL, Newell MS, Moy L, et al. Breast cancer screening in women at higher-than-average risk: recommendations from the ACR. J Am Coll Radiol 2018;15:408–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kuhl CK, Schrading S, Strobel K, et al. Abbreviated breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): first postcontrast subtracted images and maximum-intensity projection-a novel approach to breast cancer screening with MRI. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2304–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mango VL, Morris EA, David Dershaw D, et al. Abbreviated protocol for breast MRI: are multiple sequences needed for cancer detection? Eur J Radiol 2015;84:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen SQ, Huang M, Shen YY, et al. Abbreviated MRI Protocols for Detecting Breast Cancer in Women with Dense Breasts. Korean J Radiol 2017;18:470–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Moschetta M, Telegrafo M, Rella L, et al. Abbreviated combined MR protocol: a new faster strategy for characterizing breast lesions. Clin Breast Cancer 2016;16:207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Heacock L, Melsaether AN, Heller SL, et al. Evaluation of a known breast cancer using an abbreviated breast MRI protocol: correlation of imaging characteristics and pathology with lesion detection and conspicuity. Eur J Radiol 2016;85:815–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Harvey SC, Di Carlo PA, Lee B, et al. An abbreviated protocol for high-risk screening breast MRI saves time and resources. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Grimm LJ, Soo MS, Yoon S, et al. Abbreviated screening protocol for breast MRI: a feasibility study. Acad Radiol 2015;22:1157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Machida Y, Shimauchi A, Kanemaki Y, et al. Feasibility and potential limitations of abbreviated breast MRI: an observer study using an enriched cohort. Breast Cancer 2017;24:411–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Oldrini G, Derraz I, Salleron J, et al. Impact of an abbreviated protocol for breast MRI in diagnostic accuracy. Diagn Interv Radiol 2018;24:12–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Panigrahi B, Mullen L, Falomo E, et al. An abbreviated protocol for high-risk screening breast magnetic resonance imaging: impact on performance metrics and BI-RADS assessment. Acad Radiol 2017;24:1132–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Petrillo A, Fusco R, Sansone M, et al. Abbreviated breast dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging for lesion detection and characterization: the experience of an Italian oncologic center. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;164:401–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Choi BH, Choi N, Kim MY, et al. Usefulness of abbreviated breast MRI screening for women with a history of breast cancer surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;167:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]