Abstract

The aim of this study is to investigate five hypothesized mechanisms of causation between depression and condomless sex with ≥ 2 partners (CLS2+) among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), involving alternative roles of self-efficacy for sexual safety and recreational drug use. Data were from the AURAH cross-sectional study of 1340 GBMSM attending genitourinary medicine clinics in England (2013–2014). Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to investigate which conceptual model was more consistent with the data. Twelve percent of men reported depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) and 32% reported CLS2+ in the past 3 months. AURAH data were more consistent with the model in which depression was considered to lead to CLS2+ indirectly via low self-efficacy for sexual safety (indirect Beta = 0.158; p < 0.001) as well as indirectly via higher levels of recreational drug use (indirect Beta = 0.158; p < 0.001). SEM assists in understanding the relationship between depression and CLS among GBMSM.

Keywords: Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM); Sexual behaviour; Depression; Structural equation modelling

Introduction

In 2017, there were 4363 new HIV diagnoses in the UK of which 53% were reported among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) [1]. Although there is evidence that new HIV diagnoses are declining in the UK, especially in large clinics in London [2], GBMSM remain the group most at risk of HIV infection. From 2014 to 2017 there has been a 61% increase in diagnoses of chlamydia and syphilis and 43% increase in diagnoses of gonorrhoea among GBMSM. While this may be due, in part, to better detection of these STIs and/or behavioural changes possibly as a result of dating apps and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use [3], the increased gonorrhoea incidence is of particular concern given that a number of antimicrobial resistant strains have recently been identified in the UK [3]. Accordingly, efforts to better understand and address condom use among GBMSM remain vital [4].

There is substantial evidence for an association between symptoms of depression and increased engagement in condomless sex (CLS), including CLS with multiple partners and partners of an unknown/sero-different HIV status [5–21], and HIV acquisition [22] in studies of GBMSM. Most of these studies have been conducted in the U.S. To date, two UK cross-sectional studies have investigated the relationship between symptoms of depression and CLS. In a 1999 genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinic sample of 122 GBMSM, a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms (HADS score ≥ 11) was observed among men who reported CLS with an HIV-positive/unknown status partner [7]. The AURAH (Attitudes to and Understanding of Risk of Acquisition of HIV) study collected data from individuals attending 20 GUM clinics in England from 2013 to 2014. Among a sub-sample of 1340 GBMSM, depressive symptoms were found to have moderate to strong associations with measures of CLS in the past 3 months, and with bacterial STI diagnosis and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) use in the past year [21]. Associations remained after adjusting for socio-demographic factors and additionally adjusting for smoking, higher-risk drinking, and recreational drug use [21]. Although cross-sectional studies have provided strong evidence for a link between depression and CLS, they cannot provide insight into the direction of association.

There are two established theories of the mechanisms by which depression may lead to sexual risk taking: social cognitive theory and cognitive escape theory. Social cognitive theory postulates that depression negatively impacts on one’s self-efficacy i.e. perceived capacity to influence life events and social conditions. Following a social cognitive perspective on behavioural management, the main requirement for effective sexual risk reduction is perceived self-efficacy to achieve sexual safety [23]. There are a number of psychosocial factors that have been hypothesized to lower one’s self-efficacy for sexual safety; drug and alcohol use, experiences of sexual coercion/abuse, and most commonly, depression [24, 25]. Cognitive escape theory suggests that some individuals may respond to threatening cues, such as risk of STI/HIV transmission, by escaping rational self-awareness [26]. Those who experience depressive symptoms may be more likely to engage in escapism as a coping strategy, characterised by fatalistic beliefs such as helplessness or powerlessness in the face of the HIV threat [27]. Such escapism may be as a result of feeling ill-equipped to mitigate the potential threat and may lead to risk taking [28, 29]. Substance use has consistently been linked to CLS [30, 31], and may be one of the key strategies used to facilitate a state of cognitive escape [32, 33].

Therefore, the mechanism of causation for the often-found link between depression and CLS may involve causal pathways via self-efficacy for sexual safety and/or recreational drug use, or via both of these factors on the same causal chain. These relationships are complicated further by the bidirectional nature of the association between depression and recreational drug use, and between self-efficacy for sexual safety and recreational drug use. Drug use may be a confounder or mediator of the association of depression with CLS, and of self-efficacy with CLS. Self-efficacy may be a confounder or mediator of the association of drug use with CLS.

Mediation analysis investigates whether the association between an exposure and outcome operates fully or partially via an intermediate factor(s) within a hypothesized causal chain [34]. Very few studies have tested mechanisms explaining the link between depressive symptoms and CLS using mediation analysis. One such study has been conducted among U.S. GBMSM (using baseline data from Project MIX, N = 1540, 2004–2006) [14]. Measures of both low self-efficacy for sexual safety and cognitive escape tendencies were found to mediate the cross-sectional association between depression and CLS with partners of unknown/HIV sero-different status in the past 3 months. In all analyses, age, income, education level, ethnicity, HIV status, and research site were adjusted for. A recent U.S. longitudinal study of GBMSM has also examined self-efficacy for sexual safety as a mediator of the relationship between number of ‘syndemic’ factors (occurrence of depression, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, substance use, and/or sexual compulsivity) and CLS with casual partners in the past 3 months [35]. At baseline (N = 197), a greater number of ‘syndemics’ was associated with CLS indirectly via low self-efficacy, but this finding was not entirely supported when investigating a longitudinal model, as changes in self-efficacy were not associated with changes in CLS over time. Finally, in a recent study of Canadian GBMSM (N = 703), poly drug use (use of three or more recreational drugs in the past 6 months) partially mediated the relationship between depression and CLS with partners of unknown/HIV sero-different status in the past 6 months [36].

There is a lack of research exploring the role of self-efficacy for sexual safety and recreational drug use on the causal pathway leading from depression to sexual risk behaviour. The aim of this study is to use data from the aforementioned AURAH study to examine and compare five conceptual models by which depression may lead to sexual risk taking. Each model has a different hypothesized mechanism of causation involving either self-efficacy or drug use, or both factors, on separate or combined causal pathways. These causal mechanisms are investigated within a conceptual model of causal connections between demographic factors, socio-economic factors, psychosocial measures, and sexual risk behaviour among GBMSM. This will be achieved using mediation analysis within the framework of structural equation modelling (SEM). SEM does not circumvent the issue that causal effects cannot be established in observational cross-sectional studies. However, it does allow for specification of relationships between variables, and of more complex relationships that distinguish between direct and indirect effects [37]. The advantage of SEM is the ability to understand the relationship between depression and CLS within the context of the hypothesized precursors of depression. This has implications for informing complex interventions that encompass targeting of multiple behaviours/social conditions along causal chains, in order to more effectively reduce/prevent sexual risk taking.

Methods

The AURAH study recruited individuals aged 18 years or over without diagnosed HIV who were attending one of 20 GUM clinics in England from June 2013 to November 2014 [38]. A total of 4380 eligible patients were approached over the study period of whom 2630 self-completed a confidential questionnaire (response rate was 60%), which collected information on demographic, socio-economic, psychosocial, health, and lifestyle factors.

In total, 1484 men were classified as GBMSM as they met at least one of the following criteria: (i) reported being gay or bisexual (including other plurisexual identity labels i.e. identities that are not explicitly based on attractions to one sex/gender [39]), (ii) reported anal sex with a man in the past 3 months, or (iii) reported having disclosed to their family, friends or workmates as being gay, bisexual and/or attracted to men. Men who did not report any sex (anal or vaginal) in the past 3 months were excluded from this analysis since this is a study of sexually active men.

Devising a Conceptual Model of Causal Connections Between Socio-economic Factors, Psychosocial Measures, and Sexual Risk Behaviour Collected in the AURAH Study; with Various Mechanisms of Causation Between Depression and Sexual Risk Behaviour

The following demographic/socio-economic and psychosocial factors collected in AURAH, which were identified as being relevant to depression and/or CLS among GBMSM, were investigated in this study: age (as a continuous variable), born in the UK (yes or no/missing), financial security i.e. enough money to cover basic needs (all of the time, most of the time, some of the time, or never), level of educational attainment (no qualifications, O levels/GCSEs, A levels, vocational qualifications, or university degree or higher), ongoing relationship with a partner (yes or no/missing), frequency of attending gay cafes, pubs, bars, nightclubs/discos or saunas (two or more times a month or less than twice a month), and concealment of sexual identity i.e. proportion of close family, friends and workmates who know that you are gay, bisexual and/or attracted to men (more than a few/missing or few/none). AURAH participants were also asked to report whether they had used recreational drugs in the past 3 months and, if so, to select which drug or drugs from the following list of 19 options; acid, anabolic steroids, cannabis, cocaine, crack, codeine, methamphetamine, MDMA, GHB/GBL, heroin, ketamine, khat, mephedrone, morphine, opium, poppers, speed, erectile dysfunction drugs, or other drug. The number of individual drugs used in the past 3 months (continuous variable) was the measure investigated in this study, given the hypothesis that vulnerability to depression and the likelihood of engaging in CLS [40] would increase with increasing numbers of drugs used.

A number of survey items were used to investigate depressive symptoms, self-efficacy for sexual safety, and levels of a supportive network. The statistical handling of these variables in SEM is described below. Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [41], a standardised inventory that inquires about frequency of occurrence of nine symptoms during the previous 2 weeks. Response options include: not at all (coded as 0), several days (coded as 1), more than half the days (coded as 2), and nearly every day (coded as 3). The PHQ-9 aims to provide a diagnostic measure of a chronic mental health condition, therefore, it is not unreasonable to assume that for many participants, symptoms may have preceded (sexual) behaviours in the past 3 months. The following statements were used to measure self-efficacy for sexual safety: (i) ‘I feel confident that, if I want to, I can make sure a condom is used during sex with any partner, in any situation’, and (ii) ‘I find it difficult to discuss condom use with any new sexual partner’. Response options included: strongly agree, tend to agree, undecided/no opinion/not relevant to me, tend to disagree, and strongly disagree. Responses were coded as 1 to 5, starting with ‘strongly agree’ (coded as 1) for the first statement and ‘strongly disagree’ (coded as 1) for the second statement. A high score amounts to low self-efficacy for both items. Levels of a supportive network were measured using a modified version of the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire [42]. This scale enquired about the level (as much as I would like, almost as much as I would like, some, but would like more, less than I would like, or much less than I would like) at which participants received the following support from other people: ‘I have people who care what happens to me’, ‘I get love and affection’, ‘I get chances to talk to someone I trust about my personal problems’, ‘I get invitations to go out and do things with other people’, and ‘I get help when I am sick in bed’. The response options were coded as 1 to 5, starting with ‘much less than I would like’ (coded as 1).

In terms of sexual behaviour, men were asked about anal sex with men, and anal or vaginal sex with women, in the past 3 months. Subsequent questions asked about CLS, including the number of partners with whom they had CLS (with response options; 1, 2–4, 5–10, or > 10). In this study, CLS with ≥ 2 partners (yes or no/missing) in the past 3 months, regardless of the gender of the partner, was investigated. This measure may confer more significant risk of STI/HIV infection than CLS with one partner, and would exclude men having CLS only with a stable partner.

A conceptual model of hypothesized causal relationships between all factors described above was devised. Of note, implicit within the conceptual model is that CLS is often a desirable behaviour for reasons of intimacy and pleasure. Sex with a new or non-regular partner may involve a perceived risk of STIs/HIV that, for some individuals, results in behavioural adaptation via condom use. Hypothesized causal relationships were derived from previous findings of other research studies (described in the discussion section), although such relationships have not been proven to be causal. Findings from the AURAH study were not used to inform hypothesized relationships. This includes previously published data on correlates of depression [21]. The postulated relationships are discussed in the context of the results of the model.

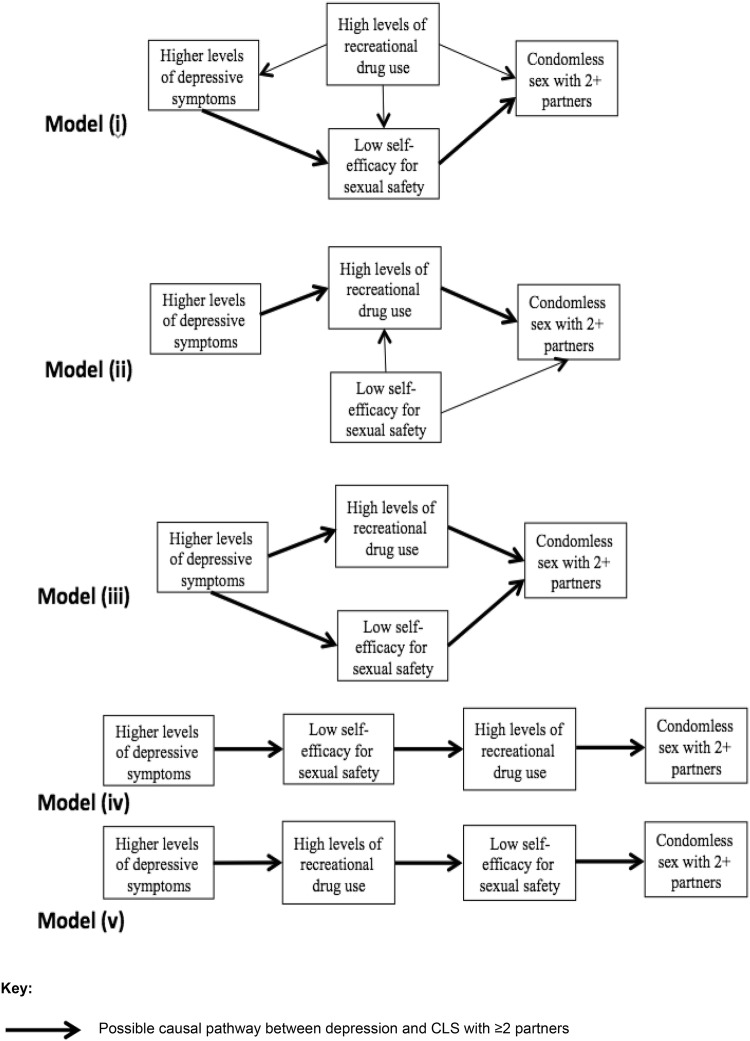

The conceptual model includes a number of hypothesized mechanisms of causation between depression and CLS with ≥ 2 partners: (i) low self-efficacy for sexual safety as the mediator (and recreational drug use as a confounder), (ii) recreational drug use as the mediator, (iii) both low self-efficacy and recreational drug use as mediators on two separate pathways, (iv) low self-efficacy as a mediator leading to recreational drug use as a mediator on the same pathway, and (v) recreational drug use as a mediator leading to low self-efficacy as a mediator on the same pathway.

Statistical Analysis

This analysis used SEM to explore the consistency of the AURAH data with five conceptual models incorporating different hypothesized mechanisms of causation between depression and CLS with ≥ 2 partners.

Depressive symptoms, self-efficacy for sexual safety, and a supportive network were considered to be unobserved (latent) variables in SEM. Latent variables are hypothetical constructs that attempt to measure real phenomena but cannot be directly measured, as they are created in order to explain observed variation in behaviours, attitudes, and feelings, which researchers can measure (observable items) [43]. For depressive symptoms, the nine observable items on the PHQ-9 [41] were used to define the construct of depression. For self-efficacy for sexual safety, two observable items (described above) were used. The five observable items on the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (described above) were used to define the construct of a supportive network [42].

Three confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were incorporated into each SEM model. In CFA, for each individual, a predefined latent variable is constructed from the average response to the observed survey items in the scale, which are weighted by the regression coefficients (factor loadings) for the relationship between the common variance among observed items in the scale and each of the observed items. If the common variance is strongly associated with the variance of an observed item, the factor loading will be larger and this observed item would be given greater weight in the derivation of the latent variable. Conversely, the more ‘measurement error’ in the observed item (variability that is not shared among observed items in the scale) the less weight this item will be given when constructing the latent variable. As a result, measurement error in the observed items is taken into account in CFA and the latent variable can be treated as if it was measured without error. In this study, treating depression as a latent variable instead of using the existing PHQ-9 scoring system was considered appropriate in the context of SEM given that latent variables account for unreliability of measurement.

Mediator pathways were incorporated and assessed by specifying indirect pathways in SEM. It was investigated whether depression was associated with CLS with ≥ 2 partners indirectly through: model (i) low self-efficacy for sexual safety, model (ii) higher levels of recreational drug use, model (iii) low self-efficacy for sexual safety and separately via higher levels of recreational drug use, model (iv) low self-efficacy for sexual safety and then recreational drug use, and model (v) recreational drug use and then low self-efficacy for sexual safety. A significant indirect effect indicates that a hypothesized intermediate factor may be on the causal pathway [44].

In all five conceptual models, mediator pathways were also incorporated to investigate the following hypotheses: (i) concealment of sexual identity causes depression indirectly via less frequent gay venue attendance and lower levels of a supportive network, (ii) concealment of sexual identity leads to lower levels of recreational drug use via less frequent gay venue attendance, (iii) higher levels of educational attainment reduces risk of depression via financial security, and (iv) older age (and therefore greater exposure to harmful anti-gay norms and discriminatory laws) lowers levels of recreational drug use via concealment of sexual identity and less frequent visits to gay venues.

SEM is an extension of multiple linear regression modelling that provides estimates of the magnitude and significance of hypothesized causal connections between sets of variables. It is best depicted via use of a causal path diagram. A path coefficient is a standardized regression coefficient (Beta weight). The interpretive value extends only to that of comparing effect sizes in order to determine which factor is of ‘greater importance’ to the model; the greater the coefficient, the greater the importance. A positive coefficient indicates a positive relationship with the outcome variable and a negative coefficient indicates the opposite, an inverse relationship with the outcome variable. The p-values correspond to the estimates adjusted for their standard errors (equivalent to the z score). p-values < 0.05 are considered to indicate significant associations.

The comparative fit index (CFI), the tucker-lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) test were used to guide the conclusion as to the model fit. The model is considered to have a satisfactory fit if: CFI and TLI are ≥ 0.90 and RMSEA is ≤ 0.08. The model is considered to have a good fit if: CFI and TLI are ≥ 0.95 and RMSEA is ≤ 0.06 (higher 90% CI ≤ 0.08; p > 0.05) [37, 45]. Given the limitations of the χ2 test, this model fit index was not used [37]. Path coefficients presented in this paper are from the conceptual model with the best fit.

All analyses were performed using Mplus statistical software [46]. A generalized weighted least square based robust estimator (the mean and variance-adjusted WLS, WLSMV) was incorporated due to the inclusion of binary/categorical outcome variables.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Of the 2630 individuals who participated in the AURAH Study, 1484 were classified as GBMSM. The current analysis is based on 1340 GBMSM who reported sex in the past 3 months. Of these, 1238 (92.4%) reported anal sex with men only, 66 (4.9%) reported sex with both men and women, and 36 (2.7%) reported sex with women only in the past 3 months [21]. Eighty-nine percent of men identified as gay (9.5% as bisexual/other plurisexual identity and 1.4% as straight) and 82.1% were of white ethnicity. Other socio-economic and psychosocial factors used in the analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-economic and psychosocial characteristics of the sample

| N = 1340 GBMSM who reported anal/vaginal sex (past 3 months) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (continuous variable) | |

| Median (IQR, 25–75%) | 31 (26–39) |

| Age groups (years) | |

| 18–24 | 235 (17.8%) |

| 25–29 | 344 (26.0%) |

| 30–34 | 255 (19.3%) |

| 35–39 | 175 (13.2%) |

| 40–44 | 125 (9.5%) |

| 45–49 | 93 (6.9%) |

| 50 + | 95 (7.1%) |

| Born in the UK | |

| Yes | 762 (56.9%) |

| No/missinga | 578 (43.1%) |

| Money to cover basic needs | |

| Always | 958 (71.7%) |

| Mostly | 281 (21.0%) |

| At times | 70 (5.2%) |

| Never | 27 (2.0%) |

| Level of educational attainment | |

| No qualifications | 34 (2.6%) |

| O levels/GCSEs | 120 (9.1%) |

| A levels | 240 (18.1%) |

| Vocational qualifications | 41 (3.1%) |

| University degree or higher | 891 (67.2%) |

| Ongoing relationship with a partner | |

| Yes | 579 (43.2%) |

| No/missinga | 761 (56.8%) |

| Number of recreational drugs used (past 3 months) (continuous variable) | |

| Median (IQR, 25–75%) | 2 (1–4) |

| Number of recreational drugs used (past 3 months) | |

| 0 | 568 (42.7%) |

| 1 | 269 (20.2%) |

| 2 | 151 (11.4%) |

| 3 | 88 (6.6%) |

| 4 | 63 (4.7%) |

| 5 + | 190 (14.3%) |

| Frequency of gay venue (gay cafes, pubs, bars, nightclubs/discos or saunas) visits | |

| Two or more times a month | 684 (51.6%) |

| Less than twice a month | 642 (48.4%) |

| Concealment of sexual identity: proportion of close family/friends/workmates who know you are gay/bisexual/attracted to men | |

| More than a few/missinga | 1284 (95.8%) |

| Few/none | 56 (4.2%) |

| Measure of supportive network: I have people who care what happens to me | |

| Less or much less than I would like | 73 (5.5%) |

| Measure of supportive network: I get love and affection | |

| Less or much less than I would like | 148 (11.1%) |

| Measure of supportive network: I get chances to talk to someone I trust about my personal problems | |

| Less or much less than I would like | 154 (11.6%) |

| Measure of supportive network: I get invitations to go out and do things with other people | |

| Less or much less than I would like | 125 (9.4%) |

| Measure of supportive network: I get help when I am sick in bed | |

| Less or much less than I would like | 205 (15.4%) |

| PHQ-9 (1) Little interest or pleasure in doing things | |

| More than half or nearly every day | 84 (6.4%) |

| PHQ-9 (2) Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | |

| More than half or nearly every day | 121 (9.2%) |

| PHQ-9 (3) Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | |

| More than half or nearly every day | 224 (16.9%) |

| PHQ-9 (4) Feeling tired or having little energy | |

| More than half or nearly every day | 207 (15.7%) |

| PHQ-9 (5) Poor appetite or overeating | |

| More than half or nearly every day | 118 (8.9%) |

| PHQ-9 (6) Feeling bad about yourself-or that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | |

| More than half or nearly every day | 169 (12.8%) |

| PHQ-9 (7) Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | |

| More than half or nearly every day | 114 (8.6%) |

| PHQ-9 (7) Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | |

| More than half or nearly every day | 114 (8.5%) |

| PHQ-9 (8) Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed/being so restless that it is hard to sit still | |

| More than half or nearly every day | 21 (1.6%) |

| PHQ-9 (9) Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way | |

| Several, more than half or nearly every day | 157 (11.9%) |

| Measure of self-efficacy for sexual safety: I feel confident that, if I want to, I can make sure a condom is used during sex with any partner, in any situation | |

| Strongly agree | 900 (67.9%) |

| Tend to agree | 342 (25.8%) |

| Undecided/no opinion/NA | 36 (2.7%) |

| Tend to disagree | 38 (2.9%) |

| Strongly disagree | 9 (0.7%) |

| Measure of self-efficacy for sexual safety: I find it difficult to discuss condom use with any new sexual partner | |

| Strongly disagree | 754 (57.0%) |

| Tend to disagree | 346 (26.2%) |

| Undecided/no opinion/NA | 81 (6.1%) |

| Tend to agree | 90 (6.8%) |

| Strongly agree | 52 (3.9%) |

aBorn in the UK: 2.1% (n = 28) missing. Ongoing relationship: 0.2% (n = 3) missing. Concealment of sexual identity: 3.0% (n = 40) missing

The prevalence of clinically significant depressive symptoms based on a common PHQ-9 cut-off score across the nine questions of ≥ 10, was 12.4% (n = 166/1340) [21], see Table 1 for individual PHQ-9 symptoms. Thirty-two percent of men did not strongly agree that they felt confident to ensure condom use (statement 1) and 10.7% tended to or strongly agreed that they had difficulty discussing condom use (statement 2), see Table 1. In total, 56.8% (n = 761) of men reported using one or more recreational drugs in the past 3 months (see Table 1 for number of drugs used). Further details of the use of specific drugs among GBMSM in the AURAH study have been published elsewhere [47]. Overall, 64% of men reported CLS with one or more partners and 32% (n = 430) reported CLS with ≥ 2 partners in the past 3 months. Of the 430 men who reported CLS with ≥ 2 partners, 90.2% (n = 388) had male CLS partners only, 6.0% (n = 26) had at least one male and at least one female CLS partner, and 3.7% (n = 16) had female CLS partners only.

Conceptual Model of Causal Connections Between Socio-economic Factors, Psychosocial Measures, and Sexual Risk Behaviour Collected in the AURAH Study; with Various Mechanisms of Causation Between Depression and Sexual Risk Behaviour

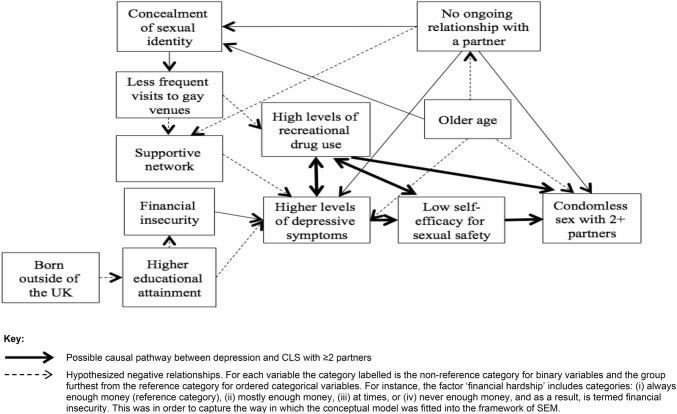

Figure 1 presents the hypotheses made about causal connections between socio-economic factors, psychosocial measures, and sexual risk behaviour collected in the AURAH study. Factors are labelled according to how they were modelled in the SEM i.e. the non-reference category for binary variables and the group furthest from the reference category for ordered categorical variables is the category that is labelled. Inverse (negative) hypothesized relationships are indicated.

Fig. 1.

Overall conceptual model of hypothesized causal connections between socio-economic factors, psychosocial measures, and sexual risk behaviour collected in the AURAH study

Exploring Various Mechanisms of Causation Between Depression and CLS with ≥ 2 Partners

Figure 2 presents five mechanisms of causation between depressive symptoms and CLS with ≥ 2 partners, whereby the five alternative roles of self-efficacy for sexual safety and recreational drug use are considered. The indirect pathway(s) specified (arrows in bold in Fig. 2) was significant in all five models (p < 0.001 for all indirect effects examined). Table 2 presents the model fit indices. Conceptual models (i), (iii), and (iv) appeared more consistent with the data as the p value for the RMSEA close-fit test was > 0.05. In model (i) depression was associated with CLS with ≥ 2 partners indirectly through low self-efficacy for sexual safety (indirect Beta = 0.158 [direct effect of depression on self-efficacy × direct effect of self-efficacy on CLS2+]; p < 0.001). In model (iii) depression was associated with CLS with ≥ 2 partners indirectly through low self-efficacy for sexual safety (indirect Beta = 0.149; p < 0.001) and separately via higher levels of recreational drug use (indirect Beta = 0.050; p < 0.001). In model (iv) depression was associated with CLS with ≥ 2 partners indirectly through low self-efficacy for sexual safety and then higher levels of recreational drug use on the same pathway (indirect Beta = 0.076; p < 0.001). Path coefficients are presented below for model (iii) since it had the best model fit (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Specific causal mechanisms investigated in five separate conceptual models (arrows between other factors remain the same as in Fig. 1)

Table 2.

Comparing model fit indices of conceptual models with differing causal pathways between depressive symptoms and CLS with ≥ 2 partners

| Models (in order of better model fit)a | RMSEA | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model (iii) | 0.047 [0.044, 0.050]; p = 0.932 | 0.963 | 0.958 |

| Model (i) | 0.049 [0.046, 0.052]; p = 0.779 | 0.961 | 0.955 |

| Model (iv) | 0.053 [0.050, 0.056]; p = 0.056 | 0.953 | 0.947 |

| Model (ii) | 0.054 [0.051, 0.057]; p = 0.019 | 0.952 | 0.945 |

| Model (v) | 0.054 [0.051, 0.057]; p = 0.010 | 0.951 | 0.944 |

aRanked according to the RMSEA first-although relative model fit statistics (information criterion statistics; AIC, BIC, and ABIC) do exist and are commonly used for model comparison, these indices cannot be estimated for models with categorical/binary variables, which use a weighted least squares estimator

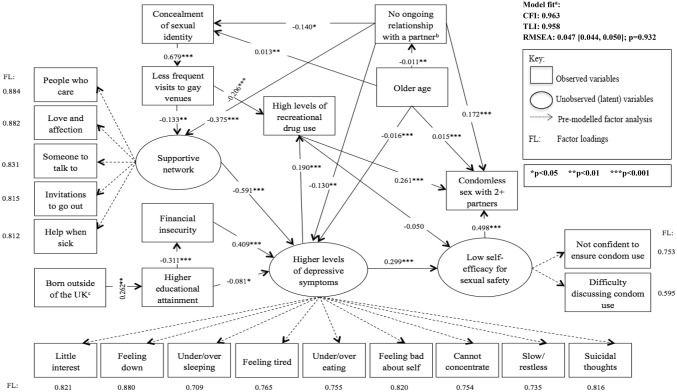

Path Coefficients in Conceptual Model (iii)

Each of the three CFAs (for depressive symptoms, self-efficacy for sexual safety, and supportive network) terminated normally, with p-values < 0.001 for all factor loadings. Figure 3 presents the results of the SEM for conceptual model (iii), including factor loadings for each observed item. All pathways specified were significant (p-values < 0.05). For instance, higher levels of depressive symptoms were associated with low self-efficacy for sexual safety (Beta = 0.299; p < 0.001) and low self-efficacy for sexual safety was associated with CLS with ≥ 2 partners (Beta = 0.498; p < 0.001). Higher levels of depressive symptoms were associated with greater number of recreational drugs used (Beta = 0.190; p < 0.001) and greater number of recreational drugs used was associated with CLS with ≥ 2 partners (Beta = 0.261; p < 0.001). Of the factors investigated to be directly associated with depression, the largest Beta coefficient was for the inverse association with higher levels of a supportive network (Beta = -0.591; p < 0.001). The second largest was for financial insecurity (Beta = 0.409; p < 0.001). The largest Beta coefficient in the conceptual model for direct effects was for the association between concealment of sexual identity and less frequent visits to gay venues (Beta = 0.679; p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

SEM of conceptual model (iii) of the link between depression and CLS with ≥ 2 partners in the AURAH study. aThe model is considered to have a satisfactory fit if: CFI and TLI are ≥ 0.90 & RMSEA is ≤ 0.08. The model is considered to have a good fit if: CFI and TLI are ≥ 0.95 & RMSEA is ≤ 0.06 (higher 90% CI ≤ 0.08), p > 0.05 [37, 45]. bThe gender of the partner was not specified. Men who had a female partner may have been less likely to disclose their sexual orientation, explaining the negative coefficient with concealment of sexual identity (a positive coefficient was hypothesized). cThe majority of men attended a clinic in London (75.9%) and may represent a select group of migrants of higher socio-economic status seeking job opportunities, explaining the positive coefficient

In terms of the indirect pathways specified, concealment of sexual identity was associated with depression indirectly through less frequent visits to gay venues and lower levels of a supportive network (indirect Beta = 0.054; p = 0.003). Concealment of sexual identity was associated with lower levels of recreational drug use indirectly via less frequent gay venue attendance (indirect Beta = − 0.140; p < 0.001). Higher educational attainment was associated with less depression indirectly through greater financial security (indirect Beta = − 0.127; p < 0.001). Finally, older age was associated with lower levels of recreational drug use via concealment of sexual identity and less frequent visits to gay venues (indirect Beta = − 0.002; p = 0.003). The indirect pathways from depression to CLS with ≥ 2 partners are described above. Of note, there was no direct association between depression and CLS with ≥ 2 partners in this model; when including an additional direct link between depression and CLS with ≥ 2 partners, the p-value for the direct effect was 0.444 (Beta = 0.034).

Discussion

Presented in this paper is the novel use of SEM to investigate five conceptual models of hypothesized causal links between socio-economic factors, depression and other psychosocial measures, and CLS with ≥ 2 partners among GBMSM. Compared to traditional regression analysis, SEM allows investigation of (complex) mediation chains and examination of the validity of the entire hypothesized conceptual model. This paper extends previous findings of a direct link between clinically significant depressive symptoms and CLS among GBMSM in the AURAH study [21], as well as in a number of other studies [5–22].

There may be numerous complex mechanisms of association between depression and sexual risk taking. Three of the five conceptual models investigated in this study were consistent with the AURAH data. In particular, they were consistent with the hypothesis that self-efficacy for sexual safety may be an important intermediary factor on the causal pathway leading to sexual risk taking. In all models, the Beta coefficient for the association with CLS with ≥ 2 partners was greater for self-efficacy than for drug use and other socio-economic factors investigated. Removing the indirect effect via low self-efficacy for sexual safety, as was done in conceptual model (ii), substantially reduced the model fit. This is in line with previous U.S. studies of GBMSM [14, 35]. Nevertheless, findings in this study indicate that recreational drug use is also an important mediator, reiterating findings from a previous study of Canadian GBMSM [36]. In the current study, data were marginally more consistent with the hypothesis that depression is associated with CLS with ≥ 2 partners either by lowering one’s self-efficacy for sexual safety or by leading to higher levels of recreational drug use on a distinct pathway. This suggests there may be important reasons for recreational drug use among GBMSM with depression other than low self-efficacy for sexual safety, which triggers drug use in order to facilitate cognitive escape from the perceived risk of STI/HIV transmission. These alternative reasons may include the use of drugs to alleviate depressive symptoms via cognitive disengagement, including drug use to lessen feelings of inadequacy in order to enable more enjoyable sexual experiences. Drugs may also be used to cope with other stressors including those common to the general population, such as finances, as well as those unique to sexual minorities, such as homophobic discrimination and heteronormative discourse. Recreational drug use could then lead to sexual risk taking via autonomic or central nervous system mechanisms that decrease self-regulation. There may also be other factors, which were not collected in AURAH, that explain (i.e. confound), fully or partially, the association observed between depression and recreational drug use: genes that confer risk for the co-occurrence of depression and substance use disorders [48], personality traits associated with sensation-seeking/sexual compulsivity [49], childhood sexual abuse [50], intimate partner violence [50], and internalized homophobia [50, 51].

In terms of the overall conceptual model, older rather than younger age was found to be associated with CLS with ≥ 2 partners. This differs from previous studies in the UK [52] and other high-income countries [53]. Differences between studies may reflect different recruitment sites, geographic differences, and use of different measures of sexual behaviour. In the SEM, not being in an ongoing relationship was associated with CLS with ≥ 2 partners. This association has been investigated in one other UK study of GBMSM [54], which failed to find a link in unadjusted analysis.

The same associations with depression that were observed in previous studies of GBMSM in high-income countries were also found in the SEM in this study: younger age, markers of lower socio-economic status, lower levels of a supportive network [16, 55], recreational drug use [10], and concealment of sexual orientation [21]. The exception to this was the association observed with relationship status in SEM, which was unlike in previous studies of GBMSM [55, 56]. Although not being in an ongoing relationship with a partner was associated with lower levels of a supportive network that was in turn associated with more depression, there also appeared to be a direct association between no ongoing relationship with a partner and less depression. The SEM might provide us with additional information given simultaneous adjustment for hypothesized associations with a supportive network, relationship status, and depression. It may be that men with low levels of social support despite having an ongoing stable partner may suffer worse depressive symptomatology than men with low levels of social support and no stable partner, due to the profound burden associated with an unhappy partnership. Another possibility is that intimate partner violence may be occurring within the context of an ongoing relationship, which may in turn lead to depression [50, 57]. The impact of an ongoing relationship on depressive symptoms is clearly complex.

Findings from the SEM also provide further insight into the relationship between minority related stressors and depressive symptoms. In Meyer’s minority stress model, one source of stress related to coping with a sexual minority status is concealment of sexual identity, with implications for psychological functioning. Identifying as a sexual minority is thought to ameliorate stress through opportunities for affiliation, social support, and coping [51]. SEM findings provide evidence in support of this theory since concealment of sexual identity was associated with depression indirectly through less frequent visits to gay venues and lower levels of a supportive network. However, being ‘out’ was also associated with higher levels of recreational drug use indirectly through more frequent visits to gay venues in the SEM. It is possible that the health benefits of disclosing one’s sexual identity may be diminished for some men via the relatively pronounced/frequent use of drugs on the gay scene.

Limitations

Given the cross-sectional design of the AURAH study it is not possible to be assured of the direction of associations. Therefore, the hypothesized causal sequence assessed in SEM may operate in the other direction, with implications for intervention. There is a need to design and conduct longitudinal studies powered to investigate depression and CLS (and STI/HIV incidence) among GBMSM, and to assess the conceptual model presented in this paper within the framework of SEM. In addition, there may be unmeasured confounding in this study.

Due to small numbers, it was not possible to stratify the sample and investigate the conceptual model separately for different identities under the umbrella of sexual minority status. This is important as gay-identified and plurisexual-identified men may have different needs and experiences. For instance, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that bisexual-identified men experience a greater burden of depressive symptomatology than do gay-identified men [55]. It was not possible in this study to investigate the concept of intersectionality; whether men subject to multiple systems of oppression, on the basis of their sexual identity, ethnicity, and socio-economic status, were at increased risk of poor mental health symptoms [58].

The AURAH study is important in the context of GUM services but the findings cannot necessarily be generalized to all GBMSM in the UK. The use of non-probability sampling methods may also limit the external validity of the sample i.e. the men recruited for AURAH may not be representative of all GBMSM attending GUM clinics in the UK. Some attempts were made to improve representativeness of the sample; at study start, all sites were asked to identify different clinic days/times each week for recruitment.

In total, 5% of GBMSM in this sample reported ever having used pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). It was not possible to ascertain whether CLS in the past 3 months occurred with or without PrEP treatment. With the PrEP Impact Trial in England and likely increase in awareness of PrEP in recent years, the prevalence of PrEP use has increased substantially since the time of the AURAH study. Future studies will need to account for PrEP use in the definition of CLS outcomes, and additionally investigate whether depression is associated with low self-efficacy for PrEP use. Studies also need to take into account knowledge of an HIV-positive partner’s HIV treatment status in defining CLS outcomes, as recent evidence has unequivocally shown that someone with an undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV [59]. However, irrespective of these factors, CLS outcomes remain important in relation to risk of transmission of other STIs.

Implications for Intervention

Among sexually active GBMSM attending GUM services, management of depression alongside interventions surrounding self-efficacy for sexual safety may play an important role in HIV/STI prevention. In order to provide individuals with the tools needed to exercise self-protective control over interpersonal sexual situations, it may be useful to offer a guided self-enablement programme that simulates experiences of mastery in the exercise of personal control [60–62]. A combination of efforts that address stress related to sexual minority status and socio-economic hardships common to the general population may be important factors in alleviation of depressive symptomatology. In particular, having a supportive network, which may be intricately linked to disclosure of one’s sexual identity and community affiliation, appears to play an important protective role with regards to depression among GBMSM. Integration of substance use services into GUM clinics or referral to such services may be highly effective in reducing future sexual risk taking. It could be suggested that interventions focused on younger men should address recreational drug use on the gay scene and interventions focused on older men should address relationship counselling, community participation, and social support.

Conclusion

There may be numerous complex mechanisms leading from depression to sexual risk behaviour among GBMSM. Multipronged STI/HIV prevention programmes that address the causes of depression among GBMSM as well as self-efficacy for sexual safety and recreational drug use, may be useful in reducing sexual risk taking. Future studies of GBMSM should move beyond examining simple direct effects of depressive symptoms on CLS and examine hypothesized relationships in an SEM framework, in order to better understand mechanisms of effect and guide prevention interventions.

Acknowledgements

The AURAH study group Ada R Miltz, Alison J Rodger, Andrew Speakman, Fiona C Lampe, Andrew N Phillips, Janey Sewell, Lorraine Sherr, Richard J Gilson, David Asboe, Nneka C Nwokolo, Amanda Clarke, Mark M Gompels, Sris Allan, Simon Collins, Christopher Scott, Sara Day, Martin Fisher, Jane Anderson, Rebecca O’Connell, Monica Lascar, Vanessa Apea, Maneh Farazmand, Susan Mann, Jyoti Dhar, Daniel R. Ivens, Tariq Sadiq, Stephen Taylor, Michael Brady, Alan Tang, Rageshri Dhairyawan, Graham J Hart, Anne M Johnson, Alec Miners, and Jonathan Elford.

AURAH clinic teams Rageshri Dhairyawan, Sharmin Obeyesekera (Barking), Vanessa Apea, John Saunders, James Hand, Nyasha Makoka (Barts and the London), Stephen Taylor, Gerry Gilleran, Cathy Stretton (Birmingham), Martin Fisher, Amanda Clarke, Nicky Perry, Elaney Youssef, Celia Richardson, Louise Kerr, Mark Roche, David Stacey, Sarah Kirk (Brighton), Mark Gompels, Louise Jennings, Caroline Holder, Katie Anne Baker (Bristol), Maneh Farazmand, Matthew Robinson, Emma Street (Calderdale & Huddersfield), Sris Allan, Abayomi Shomoye (Coventry), Nneka Nwokolo, Ali Ogilvy (56 Dean Street), Jane Anderson, Sfiso Mguni, Rebecca Clark, Cynthia Sajani, Veronica Espa (Homerton), David Asboe, Sara Day, Ali Ogilvy, Sarah Ladd (John Hunter), Susan Mann, Michael Brady, Jonathan Syred, Lisa Hamza, Lucy Campbell, Emily Wandolo, Janagan Alagarajah (Kings), Linda Mashonganyika, Jyoti Dhar, Sally Batham (Leicester), Richard Gilson, Rita Trombin, Ana Milinkovic, Clare Oakland (Mortimer Market), Rebecca O’Connell, Nyasha Makoka (Newham), Alan Tang, Ruth Wilson, Elizabeth Green, Sheila O’Connor, Sarah Kempster, Katie KeatingFedders (Reading), Daniel Ivens, Nicola Tyrrell, Jemima Rogers, Silvia Belmondo, Manjit Sohal (Royal Free), Tariq Sadiq, Wendy Majewska, Anne Patterson, Olanike Okolo, David Cox, Mariam Tarik,Charlotte Jackson, Jeanette Honigsbaum, Clare Boggon, Simone Ghosh, Bernard Kelly, Renee Aroney (St George’s), Christopher Scott, Ali Ogilvy (West London Centre for Sexual Health), and Monica Lascar, Nyasha Makoka, Elias Phiri, Zandile Maseko (Whipps Cross).

CAPRA Advisory Board Sir Nick Partridge, Kay Orton, Anthony Nardone, Ann Sullivan, Lorraine Sherr, Graham Hart, Simon Collins, Anne Johnson, Alec Miners and Jonathan Elford.

Funding

The AURAH study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP-PG-0608-10142). The AURAH Study Group acknowledges the support of the NIHR, through the Comprehensive Clinical Research Network. The views expressed in this study are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. The sponsors had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the study.

Data Availability

We have a number of planned analyses for the AURAH study, but welcome proposals for additional analysis; please contact Dr Fiona Lampe (f.lampe@ucl.ac.uk). The Study Core Group will review proposals.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

ANP has received payments for presentations made at meetings sponsored by Gilead in spring 2015. NCN has received support for attendance at conferences, speaker fees and payments for attendance at advisory boards from Gilead Sciences, Viiv Healthcare, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Bristol Myers Squibb and a research grant from Gilead Sciences.

Ethical Approval

The research protocol and all versions of the study documents (information sheet, consent form, questionnaires and insert) were approved by the designated research ethics committee (NRES Committee London-Hampstead, ref: 13/LO/0246). Based on these documents, the study subsequently received permission for clinical research at all participating National Health Service sites.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nash S, Desai S, Croxford S, et al. Progress towards ending the HIV epidemic in the United Kingdom: 2018 report. London: Public Health England; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delpech V, Desai M. Towards elimination of HIV amongst gay and bisexual men in the United Kingdom. London: Public Health England; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.PHE . Sexually transmitted infections and screening for chlamydia in England, 2018. London: Public Health England (PHE); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rana S, Macdonald N, French P, et al. Enhanced surveillance of syphilis cases among men who have sex with men in London, October 2016–January 2017. Int J STD AIDS. 2019;30(5):422–429. doi: 10.1177/0956462418814998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houston E, Sandfort T, Dolezal C, Carballo-Dieguez A. Depressive symptoms among MSM who engage in bareback sex: does mood matter? AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2209–2215. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0156-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paul JP, Catania J, Pollack L, Stall R. Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(4):557–584. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck A, McNally I, Petrak J. Psychosocial predictors of HIV/STI risk behaviours in a sample of homosexual men. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(2):142–146. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Santis JP, Colin JM, Provencio Vasquez E, McCain GC. The relationship of depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and sexual behaviors in a predominantly Hispanic sample of men who have sex with men. Am J Mens Health. 2008;2(4):314–321. doi: 10.1177/1557988307312883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemieux AF, Nehl EJ, Lin L, Tran A, Yu F, Wong FY. A pilot study examining depressive symptoms, Internet use, and sexual risk behaviour among Asian men who have sex with men. Public Health. 2013;127(11):1041–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanden Berghe W, Nostlinger C, Laga M. Syndemic and other risk factors for unprotected anal intercourse among an online sample of Belgian HIV negative men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):50–58. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0516-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fendrich M, Avci O, Johnson TP, Mackesy-Amiti ME. Depression, substance use and HIV risk in a probability sample of men who have sex with men. Addict Behav. 2013;38(3):1715–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Defechereux PA, Mehrotra M, Liu AY, et al. Depression and oral FTC/TDF pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men and transgender women who have sex with men (MSM/TGW) AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1478–1488. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pines HA, Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, et al. Sexual risk trajectories among MSM in the United States: implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis delivery. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(5):579–586. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvy LM, McKirnan DJ, Mansergh G, et al. Depression is associated with sexual risk among men who have sex with men, but is mediated by cognitive escape and self-efficacy. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1171–1179. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9678-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen YH, Raymond HF. Associations between depressive syndromes and HIV risk behaviors among San Francisco men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2017;29:1538–1542. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1307925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millar BM, Starks TJ, Grov C, Parsons JT. Sexual risk-taking in HIV-negative gay and bisexual men increases with depression: results from a U.S. National Study. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(6):1665–1675. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storholm ED, Satre DD, Kapadia F, Halkitis PN. Depression, compulsive sexual behavior, and sexual risk-taking among urban young gay and bisexual men: the P18 Cohort Study. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(6):1431–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0566-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Mayer KH. Beyond anal sex: sexual practices associated with HIV risk reduction among men who have sex with men in Boston, Massachusetts. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(7):545–550. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, et al. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant- and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(10):1002–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mimiaga MJ, Noonan E, Donnell D, et al. Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with HIV risk-taking behavior and infection among MSM in the EXPLORE Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miltz AR, Rodger AJ, Sewell J, et al. Clinically significant depressive symptoms and sexual behaviour among men who have sex with men. Br J Psychiatry Open. 2017;3(3):127–137. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.003574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20(5):731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiClemente R, Peterson J. Preventing AIDS: theories and methods of behavioral interventions. In: Bandura A, editor. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. New York: Plenum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG, Mazure CM. Self-efficacy as a mediator between stressful life events and depressive symptoms. Differences based on history of prior depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:373–378. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madden J. Neurobiology of learning, emotion, and affect. In: Bandura A, editor. Self-efficacy mechanism in physiological activation and health promoting behavior. New York: Raven Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKirnan DJ, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Sex, drugs and escape: a psychological model of HIV-risk sexual behaviours. AIDS Care. 1996;8(6):655–669. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Brennan PL. Social context, coping strategies, and depressive symptoms: an expanded model with cardiac patients. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72(4):918–928. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.4.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witte K. The role of threat and efficacy in AIDS prevention. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1991;12(3):225–249. doi: 10.2190/U43P-9QLX-HJ5P-U2J5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez AE, Wray TB, Celio MA, Monti PM. HIV-related thought avoidance, sexual risk, and alcohol use among men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2018;30(7):930–935. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1426828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, McDaid LM. Alcohol and drug use during unprotected anal intercourse among gay and bisexual men in Scotland: what are the implications for HIV prevention? Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(2):125–132. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Moore DJ, Morris SR, Smith DM, Little SJ. Clear links between starting methamphetamine and increasing sexual risk behavior: a cohort study among men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(5):551–557. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKirnan DJ, Vanable PA, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Expectancies of sexual “escape” and sexual risk among drug and alcohol-involved gay and bisexual men. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(1–2):137–154. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells BE, Golub SA, Parsons JT. An integrated theoretical approach to substance use and risky sexual behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(3):509–520. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9767-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bryan A, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. Mediational analysis in HIV/AIDS research: estimating multivariate path analytic models in a structural equation modeling framework. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(3):365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Safren SA, Blashill AJ, Lee JS, et al. Condom-use self-efficacy as a mediator between syndemics and condomless sex in men who have sex with men (MSM) Health Psychol. 2018;37(9):820–827. doi: 10.1037/hea0000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Card KG, Lachowsky NJ, Armstrong HL, et al. The additive effects of depressive symptoms and polysubstance use on HIV risk among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Addict Behav. 2018;82:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Wang X. Structural equation modeling: applications using Mplus. 1. Beijing: Higher Edication Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sewell J, Speakman A, Phillips AN, et al. A cross-sectional study on attitudes to and understanding of risk of acquisition of HIV: design, methods and participant characteristics. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(2):e58. doi: 10.2196/resprot.4873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galupo MP, Lomash E, Mitchell RC. “All of my lovers fit into this scale”: sexual minority individuals’ responses to two novel measures of sexual orientation. J Homosex. 2016;64:145–165. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1174027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daskalopoulou M, Rodger A, Phillips AN, et al. Recreational drug use, polydrug use, and sexual behaviour in HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men in the UK: results from the cross-sectional ASTRA study. Lancet HIV. 2014;1(1):e22–e31. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)70001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support. Questionnaire Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26(7):709–723. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards JR, Bagozzi RP. On the nature and direction of relationships between constructs and measures. Psychol Methods. 2000;5:155–174. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fritz MS, Mackinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sewell J, Miltz A, Lampe FC, et al. Poly drug use, chemsex drug use, and associations with sexual risk behaviour in HIV-negative men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;43:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cosgrove VE, Rhee SH, Gelhorn HL, et al. Structure and etiology of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing disorders in adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011;39(1):109–123. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parsons JT, Grov C, Golub SA. Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: further evidence of a syndemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):156–162. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):939–942. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knussen C, Flowers P, McDaid LM, Hart GJ. HIV-related sexual risk behaviour between 1996 and 2008, according to age, among men who have sex with men (Scotland) Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(3):257–259. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.045047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.CDC HIV infections attributed to male-to-male sexual contact - metropolitan statistical areas, United States and Puerto Rico, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 2012;61(47):962–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hickson F, Bourne A, Weatherburn P, Reid D, Jessup K, Hammond G. Tactical dangers. Findings from the United Kingdom Gay Men’s Sex Survey 2008. London: Sigma Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hickson F, Davey C, Reid D, Weatherburn P, Bourne A. Mental health inequalities among gay and bisexual men in England, Scotland and Wales: a large community-based cross-sectional survey. J Public Health (Oxf). 2017;39(2):266–273. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdw021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bolding G, Sherr L, Elford J. Use of anabolic steroids and associated health risks among gay men attending London gyms. Addiction. 2002;97(2):195–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buller AM, Devries KM, Howard LM, Bacchus LJ. Associations between intimate partner violence and health among men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferlatte O, Salway T, Hankivsky O, Trussler T, Oliffe JL, Marchand R. Recent suicide attempts across multiple social identities among gay and bisexual men: an intersectionality analysis. J Homosex. 2018;65(11):1507–1526. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1377489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet. 2019;33:2423–2438. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30418-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Self-efficacy Bandura A. The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelly JA. Changing HIV risk behavior: Practical strategies. New York: Guilford; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shelley G, Williams W, Uhl G, et al. An evaluation of mpowerment on individual-level HIV risk behavior, testing, and psychosocial factors among young MSM of color: the monitoring and evaluation of MP (MEM) Project. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29(1):24–37. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2017.29.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We have a number of planned analyses for the AURAH study, but welcome proposals for additional analysis; please contact Dr Fiona Lampe (f.lampe@ucl.ac.uk). The Study Core Group will review proposals.