Abstract

Introduction: This study aims to evaluate the effects of obesity on the structure of axillary lymph nodes in women with no evidence of breast or axilla pathology.

Method: In this prospective study, we documented the body mass index of 204 women who were referred for screening mammography. Two radiologists have independently viewed the mammograms to find the largest axillary lymph node and reported its dimensions. Independent sample T-test was used to evaluate the association of the above indices with participants’ body mass index. Associations between indices were investigated using multiple regression analyses.

Results: All measurements of axillary lymph nodes and hilo-cortical ratio were significantly increased with increasing body mass index (p<0.001), except for cortex width (p=0.15). There were strong associations (p < 0.001) between increasing hilum length and increasing lymph node length (R²=0.90), increasing hilum width and increasing lymph node width (R²=0.85), and increasing hilum width and decreasing cortex width (R²=0.12). There was no association between cortex width and lymph node width (R²=0.0001). Inter-rater reliability ranged from 0.49 to 0.70.

Conclusion: Our study demonstrated that axillary lymph nodes with a bigger hilum width had a smaller cortex width in obese but apparently normal population. Considering the important role of axillary lymph node cortex in their immune function, this may be a cause for immune dysfunction of axillary lymph nodes in obesity and explain the worse prognosis of breast cancer in obese women. The limited number of participants, the 2-dimensional nature of mammograms and the difficulty of measuring the dimensions of axillary lymph nodes using mammography were important limitations of this study.

Implications for practice: Obesity may result in structural change and dysfunction of axillary lymph nodes. Dysfunction of axillary lymph nodes may have a role in worse prognosis of breast cancer in obese patients.

Keywords:obesity, immune system dysfunction, lymphatic system, axillary lymph node, fat deposition.

INTRODUCTION

Lymph nodes (LNs) are secondary lymphatic tissues that are localized in strategic sites to confront foreign antigens. They generally consist of cortex, paracortex, and medulla, all having special roles in the immune system (1). However, LN cortex is the primary site of an effective immune response (2).

Previous studies have explored the influence of obesity and fat deposition in multiple organs of the human being. In the cardiovascular system, deposition of fat molecules can cause functional abnormalities and increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases (3, 4). Destructive effects of fat deposition in the liver have also been studied (5). Considering the immune system, it is known that obesity is a chronic low-grade inflammation that may alter the function of the immune system mostly by producing inflammatory cytokines (6, 7). In vivo studies on mice have also shown that obesity could alter the architecture of LNs and affect their function (8, 9).

Although obesity-induced dysfunction of the immune system and LNs has been discovered for years, the pathophysiology is still unknown. In addition, there is little available information about the effects of fat deposition in LNs. To our knowledge, there is only one study conducted by Alexander et al. at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (hereafter called the Dartmouth study), whose authors discussed the effects of obesity on axillary lymph node (ALN) size and morphology (10). In that study, the effect of obesity on LN hilum has been investigated but the cortical changes remained unclear.

It is proposed that the prognosis of breast cancer is worse in obese women (11). Axillary lymph nodes (ALNs) are the sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer and their dysfunction can be a potential mechanism to explain this poor prognosis. Because this theory has not been properly studied, this study aims to evaluate the effect of obesity on the structure of axillary lymph nodes, with specific attention to their cortical changes. We attempted to find whether there was any evidence of structural changes in ALNs in obesity which could explain their immunologic dysfunction.

METHODS

This work was approved by the Ethical Board Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. It was a prospective study conducted between February 2018 and January 2019 in Mahdieh Hospital academic center (Tehran, Iran). Individuals referred to this center for screening mammography were chosen as the study population. We assessed this group for our exclusion criteria which consisted of conditions able to alter the normal breast structure; based on the history of variation and frequency of referred individuals to the mentioned center, we decided to make our exclusion criteria more inclusive than the one used in Dartmouth study. Thus, in addition to a history of breast cancer, breast biopsy or breast surgery, we also considered a history of ALN biopsy or surgery, axillary Laser hair removal and any chronic lymphomatous diseases such as lymphoma as our exclusion criteria.

We verbally provided information about the study to all subjects who had not been excluded based on the above criteria and invited them to take part in the study. This yielded 204 participants who signed our written informed consent forms upon their enrollment. Data on age, weight and height was documented by us for each participant. In addition, a medial-lateral oblique (MLO) view of their mammography was archived for further analysis. We used two-dimensional full-field digital mammograms which were obtained with a Hologic Selenia model device.

Two senior radiologists (each with 10 years of practice) viewed the mammograms on MARCO PACS-diVision v3.6. Radiologists worked independently and were blinded to participants’ age, weight, height, and BMI. Raters searched each mammogram for the single largest LN which had at least 80% visibility. Then, they reported LN length and width, cortex width, hilum length and width and hilo-cortical ratio (HCR), all in millimeters. Like the Dartmouth study, we defined LN cortex as the dense peripheral portion and LN hilum as the lucent central area (Figure 1). The hilo-cortical ratio (HCR) was defined as the width of the hilum divided by the width of the cortex. To finalize measurements, raters jointly reassessed mammograms in which either of them had doubts or in which one or more of all indices were rated significantly different, defined as if the difference was more than ½* (Max score – Min score) for each index. Final inter-rater reliability was measured by Pearson correlation.

IBM SPSS V. 25 was used for statistical analysis. We calculated the mean of raters' scores for each index and evaluated their association with BMI, using independent-samples t-test. So, we defined obesity as BMI ≥ 30, overweight as BMI <30 and ≥ 25, and normal weight as BMI <25. Like the Dartmouth study, we have also performed a multiple regression to predict LN length from hilum length and LN width from hilum and cortex width adjusted for participants' age and breast density. However, unlike the above-mentioned study, we ran the same analysis to see if we could predict cortex width from hilum width. We drew scatterplots to check for the linear relationship between all independent variables and the dependent ones before running the analyses.

RESULTS

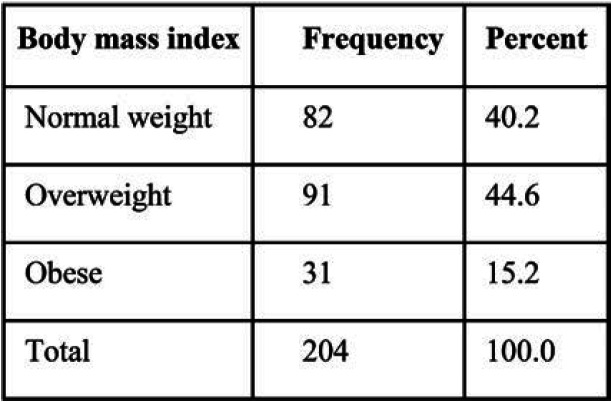

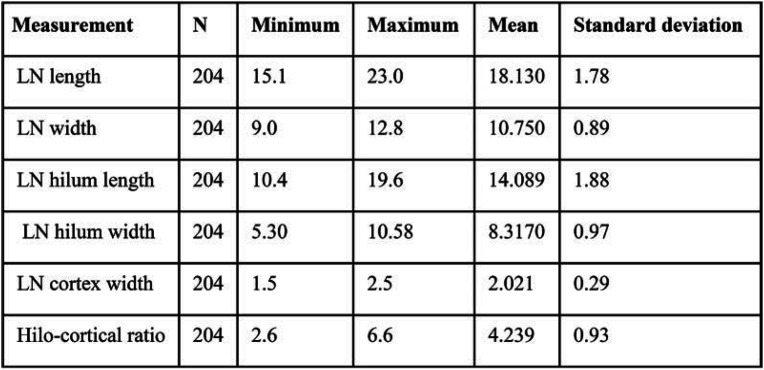

Two hundred and four LNs from the mammograms of 204 participants were identified and included in the study. The mean age of study participants was 52.8 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 6.8. The frequency of BMI categories is shown in Table 1. We did not exclude any case because of poorly visible LN or other reasons. Inter-reliability scores (Pearson r) were 0.70 for LN length, 0.70 for hilum length, 0.61 for LN width, 0.59 for hilum width, and 0.49 for cortex width. Distribution of LN measurements is summarized in Table 2.

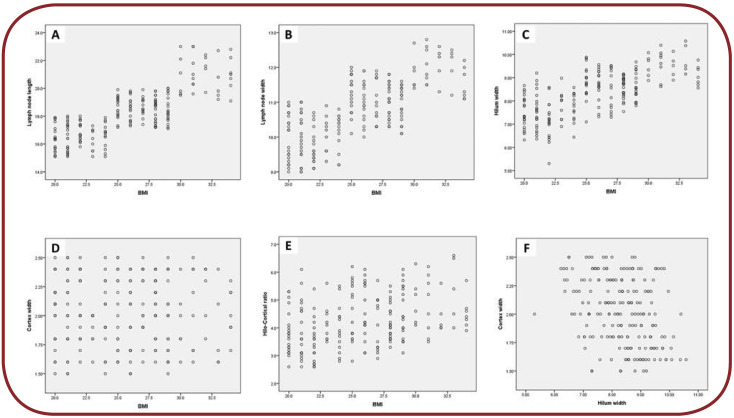

While running t-tests, all LN measurements and HCR increased significantly with increasing BMI (p<0.001), except for cortex width (p=0.15). We have also found a strong association between increasing hilum length and increasing LN length (R²=0.90, p < 0.001) and increasing hilum width and increasing LN width (R²=0.85, p < 0.001). There was no association though between cortex width and LN width (R²=0.0001). Despite the above finding, we detected a significant but weak linear relationship between hilum width and cortex width. A 1-millimeter increase in hilum width could predict a 0.1-millimeter decrease in cortex width (R²=0.12, p < 0.001). Scatterplots for assessments are shown in Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

Like many other systems in the body, obesity has diverse effects on the immune system. Alterations in the cellular immune system (12), inducing inflammatory response (13) and disrupting lymphatic tissue integrity (14) are some of the general mechanisms proposed for explaining these adverse effects. Among the studies working on the latter mechanism, many have emphasized the roles of LNs in the lymphatic system dysfunction. For example, Kim et al suggested that a high-fat diet in mice could result in mesenteric LN atrophy because of T cell apoptosis (9). A study by Weitman et al reported similar findings, showing that obesity of mice could lead to inguinal LN atrophy and reduction in the number of B and T cells; they have also detected an impairment in lymphatic tissue transport (8). On the other hand, some studies suggest that obesity can be associated with LN hyperplasia and increasing in the number of lymphocytes. Aaron et al have shown that a high-fat diet could result in an increased number of lymphocytes within the visceral LNs (15). Likewise, Magnuson et al have reported that obesity could lead to visceral (but not subcutaneous) LN hyperplasia (16). These results show that the effect of obesity on the structure and function of LNs is complicated and depends on the site of LNs.

Our study demonstrated that obesity could increase the dimensions of ALNs. Similar to the Dartmouth study, both the length and width of LNs had a strong positive association with participants’ BMI. This can be explained by fat deposition within LN hilum. We have also found that an increase in hilum width of LNs could lead to a significant decrease in their cortex width. This was inducted from a regression analysis showing that almost 12% of variance in cortex width could be significantly predicted by opposite alterations in hilum width. Although this association is not strong and we did not find a significant association between cortex width and either the width of LN or BMI, this finding may still yield important implications. On the one hand, we know that the integrated function of ALNs is important to control breast cancer metastases (17). On the other hand, the prognosis of breast cancer is shown to be worse in obese women. Some theories, such as hyperinsulinemia- induced tumoral growth and the provision of growth fuels for metastatic cells, have been proposed to explain this worse prognosis (11). Based on our finding, we believe that another theory might be the smaller cortex width of ALNs in obese women, which can impair their immune function. The smaller cortex width might be a mechanical consequence of enlarged fat infiltrated hilum, or it could occur because of the cortex cell apoptosis facilitated by the fat tissue. To clarify the exact underlying mechanisms, we suggest that further studies are needed to investigate molecular and cellular effects of obesity on ALNs using animal models.

Our study had two main limitations. Firstly, it was difficult to use mammography for careful measurement of small LN dimensions. Despite planned mechanisms to decrease measurement bias, inter-rater correlations were lower for smaller dimensions, resulting in the smallest r for measuring LN cortex width. This low precision can result in biased measurement. Secondly, it is not possible to estimate the cortical volume of lymph nodes using two dimensional images like mammograms. As a result, the lower cortex width of LNs could have been compensated by increase in other cortical dimensions. Based on this assumption, hilar infiltration may not necessarily result in a reduced cortical volume, but only in a change of its spatial dimensions. To check this assumption, we suggest that further studies should use three dimensional modalities for imaging the LNs and estimating the cortical volume by calculating and subtracting the estimated volumes of LN and hilum from each other. The last limitation of our study was the small number of participants, which may explain the low strength of the negative relationship between hilum width and cortex width. In larger studies, a greater proportion of cortex width variance might be explained by alterations in hilum width, and the relationship between cortex width and BMI or the relationship between cortex width and LN width might also become significant.

Implications for practice

Our study showed that hilar enlargement of ALNs is associated with a smaller cortex width. Because obesity and its subsequent fat infiltration significantly increase ALN hilum width, this finding may suggest an explanation for ALN dysfunction and worse prognosis of breast cancer in obese patients.

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

Funding: none declared.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the staff of the faculty members and staff of the radiology department of Shariati Hospital, Tehran, Iran, for supporting and facilitating this project.

Patient consent: Authors received written informed consents from all patients prior to their participation in the study.

FIGURE 1.

Screening mammogram of a 52-year-old female, MLO view. The left image shows an index ALN (white arrow). The right image (magnified) shows the measurement of ALN width and length (dashed arrows) and cortex (solid arrow).

TABLE 1.

BMI frequency in study patients

TABLE 2.

Lymph node (LN) measurements

FIGURE 2.

Scatterplots for linear relationships: (A) relationship between BMI and ALN length; (B) relationship between BMI and ALN width; (C) relationship between BMI and hilum width; (D) relationship between BMI and cortex width; (E) relationship between BMI and hilo-cortical ratio; and (F) relationship between hilum width and cortex width

Contributor Information

Elham KESHAVARZ, Department of Radiology, Mahdieh Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Azadeh AHANGARAN, Department of Radiology, Mahdieh Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Ensi Khalili POUYA, Department of Radiology, Mahdieh Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Radin MAHERONNAGHSH, Department of Radiology, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Mohammadreza CHAVOSHI, Department of Radiology, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Pouria ROUZROKH, Department of Radiology, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

References

- 1.Willard-Mack CL. Normal structure, function, and histology of lymph nodes. Toxicologic Pathology. 2006;5:409–424. doi: 10.1080/01926230600867727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katakai T, Hara T, Lee JH, et al. A novel reticular stromal structure in lymph node cortex: an immuno-platform for interactions among dendritic cells, T cells and B cells. International Immunology. 2004;8:1133–1142. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim S, Meigs JB. Ectopic fat and cardiometabolic and vascular risk. International Journal of Cardiology. 2013;3:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montani JP, Carroll JF, Dwyer TM, et al. Ectopic fat storage in heart, blood vessels and kidneys in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2004;28 Suppl 4:S58–S65. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiniakos DG, Vos MB, Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pathology and pathogenesis. Annual Review of Pathology. 2010;5:145–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastard JP, Maachi M, Lagathu C, et al. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. European Cytokine Network. 2006;1:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;7121:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weitman ES, Aschen SZ, Farias-Eisner G, et al. Obesity Impairs Lymphatic Fluid Transport and Dendritic Cell Migration to Lymph Nodes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e70703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim CS, Lee SC, Kim YM, et al. Visceral fat accumulation induced by a high-fat diet causes the atrophy of mesenteric lymph nodes in obese mice. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2006;6:1261–1269. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.diFlorio Alexander RM, Haider SJ, MacKenzie T, et al. Correlation between obesity and fat-infiltrated axillary lymph nodes visualized on mammography. The British Journal of Radiology. 2018;1089:20170110. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGowan MM, Eisenberg BL, Lewis LD, et al. A proof of principle clinical trial to determine whether conjugated linoleic acid modulates the lipogenic pathway in human breast cancer tissue. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;1:175–183. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2446-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samartín S, Chandra RK. Obesity, overnutrition and the immune system. Nutrition Research. 2001;1:243–262. [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Heredia FP, Gomez-Martinez S, Marcos A. Obesity, inflammation and the immune system. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2012;2:332–338. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen CJ, Murphy KE, Fernandez ML. Impact of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome on Immunity. Advances in Nutrition(Bethesda, Md) 2016;1:66–75. doi: 10.3945/an.115.010207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnuson AM, Fouts JK, Regan DP, et al. Adipose tissue extrinsic factor: Obesity-induced inflammation and the role of the visceral lymph node. Physiology & Behavior. 2018;190:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnuson AM, Regan DP, Fouts JK, et al. Diet-induced obesity causes visceral, but not subcutaneous, lymph node hyperplasia via increases in specific immune cell populations. Cell proliferation. 2017;50(5) doi: 10.1111/cpr.12365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohrt HE, Nouri N, Nowels K, et al. Profile of immune cells in axillary lymph nodes predicts disease-free survival in breast cancer. PLoS Medicine. 2005;9:e284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]