Abstract

Objectives: To determine mortality predictors following fall related fractures in older patients.

Materials and methods: Patients aged ≥ 70 years hospitalized for fall related fractures were prospectively evaluated. Mortality was the main outcome. Age, functional-cognitive function, medications, comorbidities, fall history, fear of falls were also assessed.

Outcomes: A total of 100 patients were enrolled. Ninety-one out of 100 (91%) suffered a hip fracture; 92 (92%) had surgery. The one-year post-discharge mortality was 20%. Univariate analysis revealed that older age, increased Charlson comorbidity index, low abbreviated mental test on admission, low modified Barthel index (MBI), fear of falls and delirium were significantly correlated with one-year post discharge mortality (p=.03, p=.003, p=.04, p=.005, p=.004, p=.015, respectively).

Conclusion: Age, fear of falls and Charlson comorbidity index are predictors of one-year mortality after hospitalization for fracture. It is of utmost importance to identify older patients suffering from fracture at risk of dying that may benefit from patient-centered care.

Keywords:fear of fall, hip fracture, fracture, mortality predictors, aged patients.

INTRODUCTION

More than one-third of community- living adults aged over 65 fall each year (1). Approximately 10% of falls result in major injury such as fracture, serious soft tissue injury or brain trauma (2). These injuries may cause decreased function, disability and loss of autonomy (3, 4).

Falls represent a frequent problem of aged people, requiring often orthopedic management. Orthopedic older patients are in need of holistic geriatric assessment, taking into account age, gender, comorbidities, medications, previous falling events as well as time and type of required surgical intervention. Other factors such as delirium, dementia, functional state, depression and fear of falls (FoF) should be also evaluated with the proper available tools (5, 6). Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) predicts the ten-year mortality for a patient who may have a range of comorbid conditions (7). The modified Barthel index (MBI), which is assessing the level of dependence using ten domains of activity (grooming, toilet use, feeding, transferring, walking, dressing, climbing stairs, bathing and fecal/urinary incontinence), may evaluate the functional abilities and activities of daily living (ADLs) (8).

The aim of this study was (a) to document the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients suffering a fall related fracture, (b) to estimate the one-year mortality post discharge, and (c) to identify predictors for death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective observational single-center cohort study was carried out in the Orthopaedics. Traumatology Department of the Heraklion University Hospital, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, during a one-year period. All patients aged .70 years cared for a fall related fracture were included in the study. Each patient was followed-up for one-year after discharge or until death.

At recruitment, information was extracted from the patient's medical record, along with a semi-structured personal interview with the patient or carer. Data regarding age, gender, living conditions, family status, past medical history, comorbidities, medication, use of assisting device for walking, fracture diagnosis, fall and fracture history (the year before admission), FoF, present fall circumstances, duration of hospitalization, complications, and outcome were evaluated. The Charlson comorbidity index was calculated for each patient (7). Functional abilities and activities of daily living (ADLs) were assessed using MBI (8). Patients with MBI .12 were considered functionally independent. Mental status was assessed using the abbreviated mental test (AMT) (9). A score of less than 9 implied the presence of cognitive impairment. If confusion or delirium was suspected, based on clinical evaluation, the confusion assessment method (CAM) was used (10). To have a positive CAM result, presence of acute confusion and inattention and either disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness should be demonstrated (10).

One-year post discharge, a phone semi-structured interview with the patient or his/her caregiver was conducted. Data about the following parameters were obtained: death during the preceding months, need for nursing home care and full or incomplete recovery.

Univariate analyses (Pearson Chi square for categorical variables and Spearman ñ for continuous variables) initially assessed the association between one-year survival and the following variables: FoF and living alone (treated as categorical variables), and age (years), duration of hospitalization (days), CCI, AMT and MBI scores (as continuous variables). In the following multivariate analysis, individual variables of potential clinical value for assessing risk of dying within one-year post discharge were examined through logistic regression models. Predictors in each model were variables shown by univariate analysis associated with the dependent variable at p<0.01. AMT and MBI scores were strongly correlated to each other (r=-0.577) and were not entered together in models. Instead, a categorical variable was created to indicate possible dementia by taking into account prior clinical diagnosis, AMT and MBI scores. To prevent overfitting, no more than three categorical predictors were used in each model. Statistics were calculated with GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

The present study has been approved by the hospital’s Ethical Committee. Informed consent has been given by each patient or caregiver and confidentiality of personal data was ensured.

OUTCOMES

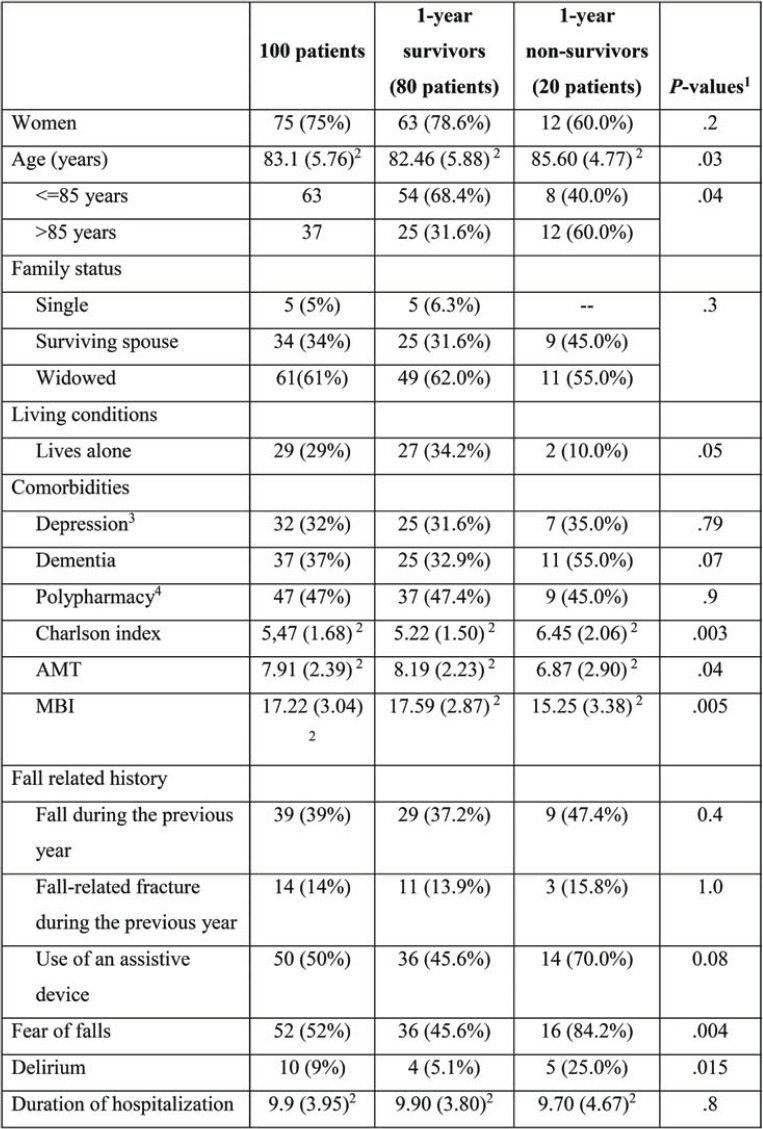

During the one-year recruitment, 100 patients were admitted to the Department of Orthopedics with a fall related fracture. Most of them suffered a hip fracture (91%). Their sociodemographic features, functional status and comorbidities are shown in Table 1.

According to information given upon admission, 29 patients were living alone, 34 with spouse, 24 with relatives (other than a spouse), 13 with a carer and six were nursing home residents. All patients had well preserved cognitive function and ability to accomplish daily living activities, except for all nursing home residents who had dementia. The most common comorbidities were as follows: hypertension (77%), musculoskeletal problems (64%), eye disorders (56%), hearing impairment (36%) and depression under treatment (32%). Depression and hypertension were more prevalent among women (p<.001 and p=.006, respectively). The average number of drugs used daily was 5.6, with antihypertensives being the most common, followed by anticoagulants and antidepressants. The mean duration of hospitalization was nine days. Ninety two out of the 100 study patients underwent operation for fracture. On average, surgery was performed 5.5 days after admission. Two patients did not require surgery, while six suffering hip fracture, all older than 84 years, were not operated due to severe comorbidities. Six developed post-operative complications: three of them had urinary tract infections, one respiratory tract infection, one hematoma and another one severe anemia due to blood loss.

No patient died during hospitalization and none was lost to follow up. Twenty (20%) patients, all with hip fracture, died within one year after discharge. The two groups, those who died and those who survived, did not differ regarding prevalence of dementia, depression, and polypharmacy, while they had similar lengths of hospitalization (Table 1). Univariate analysis revealed that survival rates were significantly higher (p<.05) for persons who lived alone, being autonomous, were aged under 85, did not develop delirium during hospitalization and did not express FoF (Figure 1).

Logistic regression models adjusted for age (in years), living conditions (living alone), FoF, Charlson index (Base model A) revealed that age, FoF and CCI were significant predictors of death during the following year [X2 (4) = 24.946, p < .001, Nagelkerke R2 = .361]. More specifically, the risk of death was increased by 12% for every year after the age of 70, six-fold by FoF and by 49% for every unit increase on the CCI. This model was successful in predicting survivorship by an accuracy of 96.2% and death by 31.3%. In supplementary models, dementia, delirium, AMT, and MBI were entered as single additional predictors to the base model. However, model fit was not significantly improved in any case (X² (3) = 0.001, p = .9, X² = 0.266, p =.6, X² = 0.492, p = .4, X² = 1.351, p = .3).

To ensure that the CCI did not account for failure of dementia, delirium, AMT, and MBI to emerge as significant predictors, a reduced base model was constructed (Base Model B) using age in years, living alone, and FoF as predictors, where dementia, AMT or MBI were entered as single additional predictors (X² = 19.109, p < .001, Nagelkerke R2 = .285; see Table 2), but model fit was not significantly improved by the addition of any of these three variables (X² = 0.435, p = .5, X² = 0.513, p = .5, X² = 1.820, p = .2, X² = 2.437, p = .07).

CONCLUSION

The present study has shown a mortality rate of 20% during the first year after discharge among older patients treated for fractures after a fall. This finding is in accordance with the literature reporting 14 to 30% similar death rates (3). The present findings confirm those by other authors describing significant correlation of older age (> 85 years old), increased CCI, low AMT at admission, low MBI, FoF and delirium with oneyear mortality after discharge (3, 5, 11-14). A systematic review and meta-analysis by Smith et al in 2014, showed four key characteristics associated with risk of mortality within the year following hip fracture surgery: abnormal ECG, cognitive impairment, age > 85 years and pre-fracture mobility (15). Although in the present population the prevalence of dementia was low and, in most cases, mild to moderate as indicated by the high level of independency observed, there was an association of dementia with one-year post hospitalization mortality. Other investigators have also reported male gender and polypharmacy associated with mortality after hip fractures, a finding which was not confirmed by the present study (12, 16-18).

Multivariate analysis revealed only age, FoF and CCI as significant predictors of death during the first year after a fall related hip fracture. It is important to note that the functional status, as expressed by MBI, was not a predictor of the one-year mortality as also observed by Katelaris et al (19).

Fear of falls, which was reported by 52% of all study patients independently of previous similar events, revealed a significant predictor for one-year mortality; FoF can lead to inactivity and avoidance of performing exercises to improve muscle strength and postural control and that may further lead to decreased physical performance and increased fall rate (20). The present findings support recent notion that FoF is an increasingly recognized mortality predictor, easily detected. A seven-year follow-up longitudinal study in geriatric population showed that participants with FoF, especially males aged 65 years and older, had an increased risk of mortality (aHR 1.17, 95% CI 1.00–1.38) after adjusting for covariates (21). Focusing in a population with a hip fracture, two other longitudinal studies report FoF as a mortality risk factor (22, 23). Having in mind that accumulating evidence identifies FoF as a modifiable situation, routine screening for FoF can be suggested among geriatric patients, especially those with hip fractures to optimize health services distribution.

Findings regarding the importance of CCI as a mortality predictor are controversial in the literature. Hindmarsh et al found CCI as a significant predictor of mortality after hip fracture in a retrospective study from New South Wales, Australia (12). However, Bullow et al did not confirm CCI as a mortality predictor among patients of the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Registry (24).

Strengths of the present study is the prospective design, the relative long duration of observation (one-year post discharge), the comprehensive geriatric assessment resulting in a holistic approach of the old age patient with a fall related fracture and the identification of an easily detected mortality predictor, namely FoF. However, this study has some limitations: it included a relatively small number of patients, and all of them were from a single center.

We conclude that older age, increased CCI and FoF are important predictors of one-year mortality post discharge after a fall related fracture. Hence, assessing these predictors for identifying aged patients with increased risk of dying in everyday clinical practice may help to reduce post fracture mortality.

Conflict of interests: none declared

Financial support: none declared.

Acknowledgments: We thank Dr Panagiotis Simos for consultation regarding the statistical analysis.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of all patients (those who survived the first-year post discharge and those who died)

TABLE 2.

Results of logistic regression models predicting death within one-year post surgery

FIGURE 1.

Survival rates according to clinical and sociodemographic characteristics

Contributor Information

Magdalini VELEGRAKI, Internal Medicine Department, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Petros IOANNOU, Internal Medicine Department, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Constantinos TSIOUTIS, School of Medicine, European University Cyprus.

Garyfalia S. PERSYNAKI, Nephrology Department, General Hospital of Rethymnon, Crete, Greece

Emmanouil PEDIADITIS, Internal Medicine Department, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Christos KOUTSERIMPAS, Orthopaedics and Traumatology Department, “251” Hellenic Air Force General Hospital of Athens, Greece.

George KONTAKIS, Orthopaedics and Traumatology Department, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Kalliopi ALPANTAKI, Orthopaedics and Traumatology Department, “Venizeleio” General Hospital, Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

George SAMONIS, Internal Medicine Department, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Symeon H. PANAGIOTAKIS, Internal Medicine Department, University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece

References

- 1.Bishop CE, Gilden D, Blom J, et al. Medicare spending for injured elders: are there opportunities for savings? Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:215–223. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.6.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:897–902. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahamsen B, van Staa T, Ariely R et al. Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1633–1650. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0920-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koutserimpas C, Samonis G, Vrentzos E, et al. In-hospital falls in older patients: A prospective study at the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35:64. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan MP, Kamaruzzaman SB, Zakaria MI, et al. Ten-year mortality in older patients attending the emergency department after a fall. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:111–117. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, et al. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10:61–63. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodkinson HM. Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1972;1:233–238. doi: 10.1093/ageing/1.4.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA ,et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey L, Mitchell R, Brodaty H, et al. Differing trends in fall-related fracture and non-fracture injuries in older people with and without dementia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;67:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hindmarsh D, Loh M, Finch CF, et al. Effect of comorbidity on relative survival following hospitalisation for fall-related hip fracture in older people. Australas J Ageing. 2014;33:E1–E7. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karademir G, Bilgin Y, Ersen A, et al. Hip fractures in patients older than 75 years old: Retrospective analysis for prognostic factors. Int J Surg. 2015;24(Pt A):101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marottoli RA, Berkman LF, Leo-Summers L, et al. Predictors of mortality and institutionalization after hip fracture: the New Haven EPESE cohort. Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1807–1812. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith T, Pelpola K, Ball M, et al. Pre-operative indicators for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2014;43:464–471. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, et al. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet. 1999;353:878–882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kragh Ekstam A, Elmstahl S. Do fall-risk-increasing drugs have an impact on mortality in older hip fracture patients? A population-based cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:489–496. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S101832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panula J, Pihlajamaki H, Mattila VM, et al. Mortality and cause of death in hip fracture patients aged 65 or older: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katelaris AG, Cumming RG. Health status before and mortality after hip fracture. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:557–560. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo AX, Brown CJ, Sawyer P, et al. Life-space mobility declines associated with incident falls and fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:919–923. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang HT, Chen HC, Chou P. Fear of falling and mortality among community-dwelling older adults in the Shih-Pai study in Taiwan: A longitudinal follow-up study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:2216–2223. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visschedijk J, Achterberg W, Van Balen R, et al. Fear of falling after hip fracture: a systematic review of measurement instruments, prevalence, interventions, and related factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1739–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker C, Gebhard F, Fleischer S, et al. [Prediction of mortality, mobility and admission to long-term care after hip fractures]. Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:32–38. doi: 10.1007/s00113-002-0475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bulow E, Cnudde P, Rogmark C, et al. Low predictive power of comorbidity indices identified for mortality after acute arthroplasty surgery undertaken for femoral neck fracture. Bone Joint J. 2019;1:104–112. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B1.BJJ-2018-0894.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]