Abstract

Background Clinical characteristics of patients with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may present differently within and outside the epicenter of Wuhan, China. More clinical investigations are needed. Objective The study was aimed to describe the clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, and therapeutic methods of COVID-19 patients in Hunan, China. Setting The First Hospital of Changsha, First People’s Hospital of Huaihua, and the Central Hospital of Loudi, Hunan province, China. Methods This was a retrospective multi-center case-series analysis. Patients with confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis hospitalized at the study centers from January 17 to February 10, 2020, were included. The following data were obtained from electronic medical records: demographics, medical history, exposure history, underlying comorbidities, symptoms, signs, laboratory findings, computer tomography scans, and treatment measures. Main outcome measure Epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics and treatments. Results A total of 54 patients were included (51 had the common-type COVID-19, three had the severe-type), the median age was 41, and 52% of them were men. The median time from the first symptoms to hospital admission was seven days. Among patients with the common-type COVID-19, the median length of stay was nine days, and 21 days among patients with severe COVID-19. The most common symptoms at the onset of illness were fever (74.5%), cough (56.9%), and fatigue (43.1%) among patients in the common-type group. Fourteen patients (37.8%) had a reduced WBC count, 23 (62.2%) had reduced eosinophil ratio, and 21 (56.76%) had decreased eosinophil count. The most common patterns on chest-computed tomography were ground-glass opacity (52.2%) and patchy bilateral shadowing (73.9%). Pharmacotherapy included recombinant human interferon α2b, lopinavir/ritonavir, novaferon, antibiotics, systematic corticosteroids and traditional Chinese medicine prescription. The outcome of treatment indicated that in patients with the common-type COVID-19, interferon-α2b, but not novaferon, had some benefits, antibiotics treatment was not needed, and corticosteroids should be used cautiously. Conclusion As of February 10, 2020, the symptoms of COVID-19 patients in Hunan province were relatively mild comparing to patients in Wuhan, the epicenter. We observed some treatment benefits with interferon-α2b and corticosteroid therapies but not with novaferon and antibiotic treatment in our study population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11096-020-01031-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Clinical characteristics, COVID-19, Infection, Pharmacotherapy

Impacts on Practice

The coronavirus infected (COVID-19) patients outside the epicenter in China generally have milder signs and symptoms.

The majority of patients outside the Corona epicenter in China belong to the common-type COVID-19 diagnosis.

Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary and overtreatments in patients with the common-type COVID-19 diagnosis, and no other alarming signs or symptoms.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a novel coronavirus which caused an outbreak of an infectious disease that originated in Wuhan, China [1–3], is now a world pandemic. The genetic characteristics of this virus proved to be significantly different from human SARS-CoV and the Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS) CoV [4]. Considering the homology of the pathogen, it has been speculated that bats are the primary source of this virus [5]. The recovery rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is about 92.7% in China, and the mortality is 5.1% globally [6]. The virus is highly infectious, spreading rapidly in human-to-human transmission, posing a dangerous threat to global public health [7, 8].

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) refers to the disease caused by the infection of SARS-CoV-2. The clinical characteristics of this disease were described [9, 10], but lacked the pathogenesis explanation and pharmacological therapies. The clinical syndrome, such as fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, fatigue, and radiographic evidence of pneumonia, were recorded. Severe patients developed shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute cardiac injury, acute kidney injury, and even death [10]. According to the clinical manifestations, the confirmed COVID-19 patients can be divided into mild, common, severe, and critical type groups based on the China National Health Commission Diagnosis and Treatment Plan of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (trial version 6) [7]. The mild group refers to mild clinical symptoms, and no sign of pneumonia is found in chest computed tomography (CT) imaging. The common type refers to patients with fever, respiratory symptoms, and the sign of pneumonia in CT scanning. Severe COVID-19 patients present with any of the following: (1) shortness of breath, plus respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/min, (2) in resting state, oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤ 93%, and 3) arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2)/Fraction of inspiration oxygen (FiO2) ≤ 300 mmHg. Critical COVID-19 patients are diagnosed by any of the following: (1) respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, (2) shock, and (3) organ failures requiring intensive care unit admission and treatment.

The first confirmed cases in China were concentrated in Wuhan, and nearly all associated with Huanan Seafood Market [10]. SARS-CoV-2 was possibly derived from the animal transmission, then spreading from person to person, and eventually into other communities. The recovery rate in Hunan Province is about 94.2%. Reports have shown that the clinical characteristics of patients are different between those infected in Wuhan and those infected outside of Wuhan [11, 12]. The clinical investigation of patients, especially outside of Wuhan, is warranted.

Aim of the study

This multi-center study was aimed to describe the clinical characteristics, laboratory parameters, and therapeutic methods of COVID-19 patients in Hunan, China.

Ethics approval

This retrospective case series was approved by the institutional ethics board of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (No. 20200123).

Methods

Study setting, patients and data collection

Our study included patients with COVID-19 diagnosed according to the World Health Organization’s interim guidance [6]. Patients were admitted to the First Hospital of Changsha, First People’s Hospital of Huaihua, and the Central Hospital of Loudi, from January 17 to February 10, 2020.

Epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics, as well as treatment and outcome data, were obtained with data collection forms from electronic medical records. Data were reviewed by a trained team of physicians. The information recorded included demographic data, medical history, exposure history, underlying comorbidities, symptoms, signs, laboratory findings, CT scans, and treatment measures. Only 37 patients with the common-type COVID-19 and the three patients with the severe-type had complete laboratory test data.

Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay for SARS-CoV-2

The specific conserved sequences of nCoV-open reading frame1ab (ORF1ab) and nucleocapsid protein N gene were used as target regions, and the expression of RNA in each sample was detected by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay (RT-RCR). Specific steps are as follows. Throat swab samples were collected from patients suspected of having SARS-CoV-2. After collection, samples were placed into a collection tube with 150 µL of virus preservation solution, and total RNA was extracted within 2 h using a respiratory sample RNA isolation kit. Then, a PCR reaction mixture containing 26 µL of PCR action buffer and 4 µL enzyme solution was added to 4 µL of the sample to perform RT-RCR. FAM (ORF-1ab region) and ROX (N gene) channels were selected to detect SARS-CoV-2, and the HEX channel was used for the internal standard. RT-PCR assay was performed under following conditions: incubation at 50 °C for 30 min and 95 °C for 1 min, 45 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, and extending and collecting fluorescence signal at 60 °C for 30 s. A cycle threshold value (Ct-value) of 40 or less for FAM or ROX channel was defined as a positive test result. Ct-values more than 40 for FAM and ROX channels and Ct-value of 40 or less for HEX channel were defined as a negative test. Also, Ct-values for FAM, ROX, and HEX more than 40 were defined as an invalid test result.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were described using the median and interquartile range (IQR). Paired Student’s t test was used to compare the differences in plasma concentrations between admission and discharge groups. Normally distributed data were analyzed by a two-sample t-test. Means for continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney test when data were not normally distributed. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc). For unadjusted comparisons, a two-sided α < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical features

A total of 54 patients were analyzed: 51 had the common-type COVID-19, and three patients had severe COVID-19. In the common type group, the median age was 41 years (IQR 31–51; range 10–76 years), 26 (51.0%) were males (Table 1). The age of patients with severe COVID-19 also had a wide range; they were 18, 37, and 74 years old, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patient with COVID-19

| Clinical characteristics | Common (N = 51) | Severe (N = 3) | Total (N = 54) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 41 (31–51) | 37 (27.5–55.5) | 41 (31–51) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 26 (51.0%) | 2 (66.7%) | 28 (51.9%) |

| Female | 25 (49.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 26 (48.1%) |

| Hospitalization Days (IQR), d | 9 (7–12) | 21 (20–24) | 9.5 (7–15) |

| First symptoms to hospital admission (IQR), d | 7 (5–9) | 9 (7.5–10.5) | 7 (5–9) |

| First symptoms to hospital discharge (IQR), d | 17 (14–21) | 30 (29.5–31.5) | 17 (14–21) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 7 (13.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 8 (14.8%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 7 (13.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 8 (14.8%) |

| Chronic liver disease | 4 (7.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (7.4%) |

| Diabetes | 3 (5.9%) | 2 (66.7%) | 5 (9.3%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2 (3.9%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Chronic bronchitis | 2 (3.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.7%) |

| No coexisting conditions | 34 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 35 (64.8%) |

| Sign and symptoms | |||

| Fever | 38 (74.5%) | 3 (100.0%) | 41 (75.9%) |

| Cough | 29(56.9%) | 3 (100.0%) | 32 (59.3%) |

| Fatigue | 22 (43.1%) | 3 (100.0%) | 25 (46.3%) |

| Expectoration | 15 (30.0%) | 3 (100.0%) | 18 (33.3%) |

| Anorexia | 12 (23.5%) | 1 (33.3%) | 13 (24.1%) |

| Muscle soreness | 6 (11.8%) | 3 (100.0%) | 9 (16.7%) |

| Shortness of breath | 4 (7.8%) | 1 (33.3%) | 5 (9.3%) |

| Pharyngalgia | 4 (7.8%) | 1 (33.3%) | 5 (9.3%) |

| Headache | 3 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.6%) |

| Chest distress | 3 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.6%) |

| Nausea | 3 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.6%) |

| Dizziness | 3 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.6%) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (3.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.7%) |

| ARDS | 0(0.0%) | 3(100.0%) | 3 (5.6%) |

| Heart rate, median (IQR) | 86.5 (78–95) | 100 (89–101.5) | 87 (78–95) |

| Respiratory rate, median (IQR), breaths/min | 20 (20–21) | 20 (20–21) | 20 (20–21) |

| Systolic pressure median (IQR), mm Hg | 119 (110–131) | 120 (116.5–145) | 119 (111.5–131) |

| Diastolic pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | 76 (71–85) | 75 (72.5–90.5) | 76 (71.5–85) |

All patients had no history of exposure to the Huanan Seafood Market. Sixteen patients lived in Wuhan for more than 6 months, 13 traveled to Wuhan recently, 14 patients had close contact with individuals diagnosed with SARS-Cov-2 infection, one patient was a nurse worked in a hospital, and 10 patients were unable to identify the source of infection. The median time from the first symptom to hospital admission was 7 days (IQR 5–9), and the median length of stay was 9 days (IQR 7–12) among patients with the common-type COVID-19. Patients with the severe-type took a longer time to be admitted from their first symptom (median, nine days; IQR 7.5–10.5) and had a more extended hospital stay (median, 21 days; IQR 20–24).

Among the 51 patients with the common-type COVID-19, 16 (31.4%) had one or more coexisting medical conditions. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (7 patients), cardiovascular disease (7), chronic liver disease (4), and diabetes (3). Two patients had cerebrovascular disease. Two patients had chronic bronchitis. Among patients who had the severe-type COVID-19, one had hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cerebrovascular disease, one had diabetes, and the other patient had no coexisting condition.

The most common symptoms at the onset of illness in the common-type group were fever (38 [74.5%]), cough (29 [56.9%]), fatigue (22 [43.1%]), expectoration (15 [30.0%]), anorexia (12 [23.5%]), and muscle soreness (6 [11.8%]). Less common symptoms were shortness of breath, pharyngalgia, headache, chest distress, dizziness, and diarrhea (Table 1). All patients with the severe-type COVID-19 had fever, cough, fatigue, expectoration, and muscle soreness as well as ARDS. All 54 patients were discharged without death occurrence.

Laboratory findings

The results of blood analysis showed some typical characteristics in patients with virus infection; however, there were limited findings that presented consistently across all patients. All the severe patients showed decreased platelet count and eosinophil ratio. The blood test also showed that in general, patients with severe COVID-19 had worse results such as electrolyte and inflammatory biomarker abnormalities than those in patients with the common-type infection. All severe COVID-19 patients had increased Ca2+, CK, CK-MB, LDH, and hs-CRP concentrations (Table 2). More detailed blood test results can be found in Figure S1.

Table 2.

Laboratory parameters of patient with common COVID-19 (total N = 40)

| Laboratory parameters | Common (N = 37) | Severe (N = 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood cell analysis | |||

| WBC count | Decreased | 14 (37.8%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Platelet count | Decreased | 2 (5.4%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| Hematocrit | Decreased | 11 (29.7%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Lymphocyte ratio | Decreased | 9 (24.3%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Eosinophil ratio | Decreased | 23 (62.2%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| Lymphocyte count | Decreased | 7 (18.9%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Neutrophil count | Decreased | 10 (27.0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Eosinophil count | Decreased | 21 (56.8%) | 2 (66.7%) |

| Basophil count | Increased | 12 (32.4%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Liver function analysis | |||

| ALT | Increased | 4 (10.8%) | 2 (66.7%) |

| AST | Increased | 4 (10.8%) | 2 (66.7%) |

| Direct bilirubin | Increased | 6(16.2%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Total protein | Decreased | 10(27.0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Albumin | Decreased | 14(37.8%) | 2 (66.7%) |

| Albumin/Globulin ratio | Decreased | 22(59.5%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| LDH | Increased | 10 (27.0%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| Kidney function analysis | |||

| BUN | Decreased | 8(21.62%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| UA | Decreased | 3(8.11%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Electrolyte analysis | |||

| K+ | Decreased | 6 (16.2%) | 2 (66.7%) |

| Na+ | Decreased | 2 (5.4%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Ca2+ | Increased | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| CK | Increased | 2(5.4%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| CK-MB | Increased | 1(2.7%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| hs-CRP | Increased | 26(70.3%) | 3 (100.0%) |

WBC white blood count, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, BUN blood urea nitrogen, UA uric acid, CK creatine kinase, CK-MB: creatine kinase-MB, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

Radiologic results

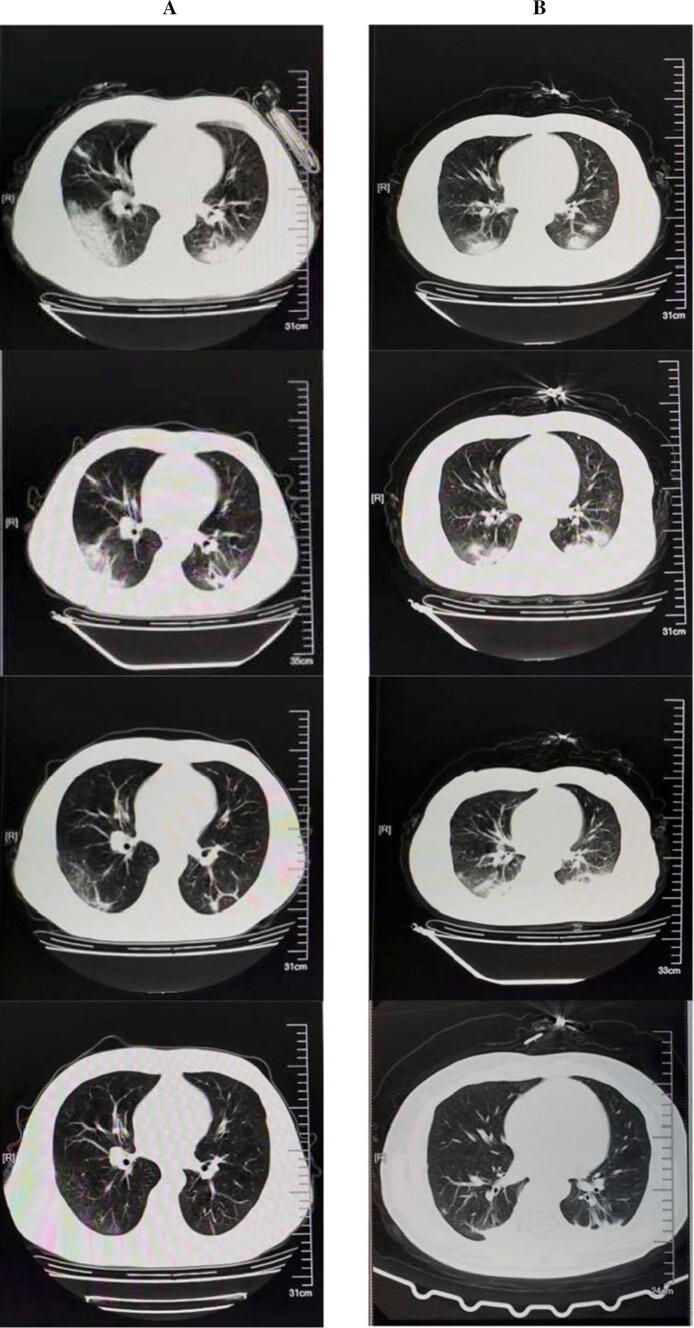

Among the 51 common-type COVID-19 patients who underwent chest CT on admission, 46 (90.2%) had imaging findings of viral pneumonia. The most common patterns were ground-glass opacity (52.2%) and patchy bilateral shadowing (73.9%) (Table 3). Figure 1 demonstrates the representative radiologic findings of two patients with COVID-19. In the early stage, COVID-19 pneumonia patients with initial lung findings were small subpleural ground-glass opacities that grew larger with crazy-paving pattern and consolidation. Lung involvement increased to consolidation up to 2 weeks after the initial disease onset. In the later stage, the lesions were gradually absorbed, leaving extensive ground-glass opacities and subpleural parenchymal bands. All the severe patients had ground-glass opacity in their CT results.

Table 3.

Radiologic findings at presentation of patient with COVID-19 (total N = 49)

| Radiologic findings | Common (N = 46) | Severe (N = 3) |

|---|---|---|

| Ground glass opacity | 24 (52.2%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| Unilateral patchy shadows | 3 (6.5%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Bilateral patchy shadows | 34 (73.9%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Interlobular septal thickening | 4 (8.7%) | 2 (66.6%) |

| Fibrous stripes | 1 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Consolidation | 3 (6.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Fig. 1.

Transverse chest computed tomograms from a 37-year-old man (a) and a 34-year-old woman (b), showing ground glass opacity and crazy-paving pattern and consolidation on day 1 after symptom onset, the lesions were gradually absorbed leaving extensive ground glass opacities and subpleural parenchymal bands

Treatment

All 54 patients were admitted to isolation wards and received oxygen therapy and ventilatory support. We analyzed 37 patients (common-type) and three severe patients who had complete laboratory tests record. Among 37 common type patients, 36 patients (97.3%) received antiviral treatment, 29 patients (78.5%) were given probiotics (lactobacillus bifidus triple live bacteria tablets), 28 patients (75.7%) were treated with traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs), 22 patients (59.5%) received antibiotics (fluoroquinolone or β-lactams), 11 patients (29.7%) were given systematic corticosteroids, 18 patients (48.6%) were treated with recombinant human interferon α2b injection (IFN-α2b), and 13 patients (35.1%) received recombinant cytokine gene-derived protein injection (Novaferon). IFN-α2b (5 million units diluted with 2 mL sterile water) was administered twice a day via inhalation by high-pressure oxygen atomization.

The three severe COVID-19 patients were treated with antivirals, antibiotics, novaferon, and systematic corticosteroids. All 54 discharged patients were based on a reduction of fever for at least 3 days, with improved evidence on CT and respiratory symptoms. Also, nucleic acid tests were negative at a minimum of two times.

At the point of discharge, many clinical indicators of COVID-19 patients were improved. Among them, the CK and hs-CRP values were significantly decreased. The number of platelets, eosinophil ratio, lymphocyte, monocyte, neutrophil, eosinophil, and plateletocrit was increased significantly (Table 4).

Table 4.

Laboratory changes of discharged common COVID-19 patients (N = 37)

| Parameters | Normal Range | Admission median (IQR) | Discharge median (IQR) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K+, mmol/L | 3.5–5.5 | 3.81 (3.66–4.10) | 4.25 (3.90–4.74) | 0.000** |

| Na+, mmol/L | 133–149 | 135.50 (134.35–136.75) | 137.20 (136.15–138.25) | 0.000** |

| Chlorine, mmol/L | 95–110 | 101.90 (98.90–103.05) | 101.90 (100.15–103.55) | 0.459a |

| Ca2+, mmol/L | 1.05–1.35 | 1.19 (1.17–1.21) | 1.22 (1.20–1.25) | 0.001a ** |

| ALT, U/L | 0–42 | 22.34 (14.82–29.07) | 23.07 (16.81–32.79) | 0.124a |

| AST, U/L | 0–37 | 23.38 (18.88–32.07) | 22.00 (17.75–29.50) | 0.064 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 3.4–20.5 | 12.43 (9.80–16.61) | 12.36 (8.99–17.06) | 0.504 |

| Direct bilirubin, μmol/L | 0–6.8 | 3.99 (2.95–6.35) | 3.54 (2.58–5.93) | 0.994 |

| Indirect bilirubin μmol/L | 5.1–13.7 | 8.48 (6.68–11.19) | 9.17 (6.63–12.40) | 0.226 |

| Total protein, g/L | 60–83 | 61.89 (59.37–63.81) | 64.85 (61.27–66.23) | 0.007** |

| Albumin, g/L | 35–55 | 36.22 (32.91–39.72) | 34.79 (32.82–39.85) | 0.777 |

| Globulin, g/L | 20.2–29.5 | 25.90 (23.30–28.50) | 27.60 (25.70–31.20) | 0.000** |

| Albumin/Globulin (A/G) | 1.50–2.50 | 1.42 (1.21–1.68) | 1.28 (1.08–1.51) | 0.003** |

| Total bile acid, μmol/L | 0.0–15 | 2.99 (1.79–5.63) | 4.13 (2.58–6.66) | 0.362a |

| BUN,mmol/L | 2.86–8.2 | 3.71 (2.97–4.38) | 4.42 (3.45–5.29) | 0.001** |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 19.8–87.1 | 44.19 (40.18–51.72) | 55.70 (47.16–62.35) | 0.000** |

| UA, μmol/L | 149–430 | 226.70 (195.70–254.30) | 251.60 (193.10–304.50) | 0.044* |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 3.9–6.1 | 5.82 (4.98–6.93) | 5.34 (4.85–6.23) | 0.003** |

| CK, U/L | 10–190 | 63.70 (37.40–97.30) | 35.70 (28.15–54.60) | 0.000a ** |

| CK-MB, U/L | 0–24 | 10.20 (6.80–12.20) | 7.20 (4.50–11.25) | 0.062 |

| LDH, U/L | 135–225 | 172.70 (133.60–206.80) | 165.10 (140.90–193.10) | 0.167 |

| Hs-CRP mg/L | 0.0–8.0 | 17.05 (6.65–29.36) | 9.88 (4.87–22.31) | 0.007** |

| WBC count, × 109/L | 4–10 | 4.58 (3.27–5.45) | 6.28 (5.32–7.92) | 0.000a ** |

| RBC count, × 1012/L | 3.50–5.5 | 4.39 (4.07–4.65) | 4.37 (4.20–4.70) | 2.242 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 110–160 | 127.00 (118.00–139.50) | 129.00 (121.00–140.00) | 2.220 |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | 100–300 | 173.00 (134.50–229.00) | 277.00 (203.50–324.50) | 0.000** |

| Hematocrit, % | 37.0–54.0 | 39.10 (36.70–42.35) | 40.20 (37.20–42.50) | 0.048* |

| MCV, fl | 80–100 | 90.90 (88.25–92.95) | 90.80 (87.95–92.90) | 0.293 |

| MCH, pg | 27.0–34.0 | 29.20 (28.50–29.85) | 29.30 (28.60–29.80) | 0.941 |

| MCHC, g/L | 320–360 | 323.00 (319.00–328.50) | 323.00 (318.00–326.00) | 0.648a |

| Lymphocyte ratio, % | 20–40 | 27.00 (19.65–30.60) | 26.10 (17.55–30.15) | 0.484a |

| Monocyte ratio, % | 3.0–12.0 | 7.60 (6.30–9.50) | 7.50 (6.20–9.30) | 0.521a |

| Neutrophil ratio, % | 50.0–70.0 | 64.90 (60.30–72.45) | 66.40 (59.65–72.70) | 0.566 |

| Eosinophil ratio, % | 0.5–5.0 | 0.30 (0.10–1.00) | 1.30 (0.60–2.05) | 0.014* |

| Basophil ratio, % | 0.0–1.0 | 0.30 (0.20–0.30) | 0.30 (0.20–0.40) | 0.071a |

| Lymphocyte count, × 109/L | 0.8–4.0 | 1.12 (0.91–1.42) | 1.60 (1.21–1.87) | 0.000** |

| Monocyte count, × 109/L | 0.12–1.2 | 0.35 (0.27–0.42) | 0.46 (0.36–0.61) | 0.003** |

| Neutrophil count, × 109/L | 2.00–7.00 | 2.93 (1.98–3.72) | 4.26 (3.21–5.67) | 0.002** |

| Eosinophil count, × 109/L | 0.02–0.5 | 0.01 (0.00–0.05) | 0.09 (0.04–0.12) | 0.000** |

| Basophil count, × 109/L | 0.00–0.10 | 0.01 (0.01–0.02) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | 0.000a ** |

| RDW-CV | 11.0–16.0 | 12.00 (11.80–12.50) | 12.00 (11.70–12.45) | 0.205a |

| RDW-SD | 35.0–56.0 | 38.50 (37.10–39.75) | 37.80 (36.90–39.00) | 0.081* |

| PDW, % | 9.0–17.0 | 16.40 (16.05–16.70) | 16.40 (16.15–16.60) | 0.778 |

| MPV, fl | 6.5–12.0 | 9.50 (8.95–10.85) | 9.60 (8.80–10.10) | 0.230 |

| Plateletocrit, % | 0.108–0.282 | 0.16 (0.13–0.22) | 0.26 (0.21–0.29) | 0.000** |

Data are given as median (IQR). P values indicate differences between discharged and admission patients by paired-sample t test

ap values are determined by Mann–Whitney test

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 was considered statistically significant

We analyzed different subgroups of patients with COVID-19 based on types of the pharmacotherapies they received. The findings showed that IFN-α2b therapy increased K+ (p < 0.01) and Ca2+ (p < 0.05) concentration and decreased total bilirubin value (p < 0.05). The CK value was significantly reduced (p < 0.05) in patients who received corticosteroid therapy. Patients who received corticosteroid treatment had increased total bile acid (p < 0.05) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (p < 0.01). Novaferon treatment did not lower CK values (p < 0.05), but decreased BUN (p < 0.01) compared to patients who did not receive the therapy. We also found that patients who received antibiotic treatment had decreased creatinine (p < 0.05), platelets (p < 0.05), and plateletocrit (p < 0.05) values, but increased total bilirubin (p < 0.05), indirect bilirubin (p < 0.01) and total bile acid (p < 0.05) concentrations (Table 5, Figure S2).

Table 5.

Comparison of differential values (DV) (discharge -admission) in COVID-19 patients with different treatment (N = 37)

| Drugs | Parameters | Did not receive the treatment | Received the treatment | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-α2b (received N = 18) | K+, mmol/L | 0.24 (− 0.17 to 0.59) | 0.675 (0.41–1.03) | 0.001** |

| Ca2+, mmol/L | 0.01(− 0.20 to 0.05) | 0.04 (0.01–0.63) | 0.013* | |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 3.00(− 3.31 to 10.09) | − 1.79 (− 5.75 to 3.16) | 0.025* | |

| Corticosteroids (received N = 11) | Total bile acid, μmol/L | − 0.32 (− 2.50 to 2.12) | 3.93 (− 0.04 to 8.68) | 0.044*a |

| BUN, mmol/L | 0.55 (− 0.29 to 1.24) | 1.92 (0.40–2.91) | 0.002* | |

| CK, U/L | − 8.90 (− 43.05 to 2.30) | − 47.60 (− 60.30 to 13.70) | 0.031*a | |

| Basophil ratio, % | 0.30 (0.20–0.40) | 0.20 (0.10–0.20) | 0.005**a | |

| Basophil count, × 109/L | 0.01 (0.01–0.02) | 0.01 (0.00–0.01) | 0.024*a | |

| MPV, fl | 9.65 (9.18–11.00) | 9.00 (8.40–.90) | 0.048*a | |

| Nova (received N = 13) | BUN, mmol/L | 1.225 (0.48–2.08) | − 0.25(− 0.88 to 0.63) | 0.000** |

| CK, U/L | − 31.5 (− 66.9 to 8.9) | − 3.9 (− 31.35 to 13.85) | 0.018**a | |

| Antibiotic (received N = 22) | Total bilirubin, μmol/L | − 3.31 (− 5.35 to 2.06) | 2.76 (− 1.85 to 8.04) | 0.042*a |

| Indirect bilirubin, μmol/L | − 2.08 (− 3.79 to 1.07) | 3.29 (− 1.15 to 6.24 | 0.008**a | |

| Total bile acid, μmol/L | − 1.24 (− 3.21 to 0.09) | 1.185 (− 0.37 to 4.92) | 0.027*a | |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 13.8 (5.89–34.14) | 5.66 (− 1.76 to 11.71) | 0.028*a | |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | 236 (139.00–293.00) | 147 (128.30–193.80) | 0.016* | |

| Plateletocrit, % | 0.22 (0.14–0.25) | 0.15 (0.13–0.18) | 0.010* |

Data are given as median (IQR). P values indicate differences between unused and used patients

ap values are determined by Mann–Whitney test

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 was considered statistically significant

Discussion

In this study, we reported the clinical characteristics of patients with COVID-19 as well as therapies they received during hospitalization in Hunan province, China. None of the 54 infected patients had been exposed to the Huanan Seafood Market, suggesting human to human transmission, as previously reported [7, 11]. In this study, 51 out of the 54 patients fell into the common-type group. Most of these patients had mild to moderate symptoms. The median age of this group of patients was 41 years, and the median length of hospital stay was 9 days. The common clinical manifestations were fever, cough, and fatigue. A few patients had pharyngeal pain and muscle pain. These cases usually have a long incubation period and may present atypical symptoms as the first symptoms, thus becoming a potential source of infection. Ground-glass opacity and patchy bilateral shadowing were hallmarks of CT scans. For the three cases with a severe-type of COVID-19, the median age was 37 years, and the median hospitalization was 21 days. The median duration from the first symptoms to hospital admission was 9 days. All of them had fever, cough, fatigue, expectoration, and muscle soreness, as well as ADRs.

Only 37 (common-type) and three severe COVID-19 patients had complete laboratory test data. The laboratory test results showed that the patients with the common-type of COVID-19 experienced mild illness. For example, only some of these patients had decreased WBC count, decreased platelet count, decreased hematocrit, decreased lymphocyte ratio, decreased eosinophil ratio, decreased lymphocyte, decreased neutrophil, decreased eosinophil and increased basophil values. About 27.0% of these patients had increased LDH, and 70.3% of them had increased hs-CRP concentrations. Whereas, the patients with the severe-type COVID-19 had more severe symptoms such as ARDS.

In this study, all patients were treated in isolation with a high nasal flow of oxygen. When discharged, many clinical parameters were back to normal, including CK (p < 0.0.000), hs-CRP (p < 0.0.01), platelets (p < 0.0.01, eosinophil ratio (p < 0.0.01), lymphocyte (p < 0.0.01) and eosinophil count (p < 0.0.01). We also found that the common-type of COVID-19 patients had a better overall recovery, which may be related to their fewer complications. Older age patients admitted had a good prognosis, but follow-up attention should be paid to monitor for long-term complications (particularly pulmonary changes, such as pulmonary fibrosis).

Among patients with common-type COVID-19, 97.3% of them received antiviral treatment, lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r). LPV/r is a new proteinase inhibitor used in antiretroviral therapy for HIV infected disease [13]. LPV/r was recently used to treat COVID-19 infection, however, the study did not show any treatment benefit beyond the standard of care for severe-type adult COVID-19 patients [14]. Due to lack of control cases, we were not able to analyze the treatment benefit of LPV/r in our study as well. About 49% of the patients were treated with IFN-α2b, which increased patients’ serum K+ and Ca2+ and decreased the total bilirubin concentrations. It has been reported that IFN-α2b showed a therapeutic effect on SARS-CoV infection in rhesus macaques [15] and hand, foot, and mouth disease in humans [16]. Patients who received systematic corticosteroids showed a significant decrease in CK concentration. Elevated CK is present in the serum when there is cell injury, fever, and stress [17]. Glucocorticoids also have anti-inflammatory and antiviral effects and can be used for a short time.

Meanwhile, 35.1% of patients received novaferon, a new type of interferon possessing anti-tumor and antiviral activities [18]. However, there was no treatment effect on patients with COVID-19 infection. Almost 60% of the patients received antibiotic treatment. No treatment effects were observed, yet adverse effects on liver and kidney function were found, suggesting antibiotics treatment was not recommended among patients with the common-type COVID-19 infection. Patients with severe COVID-19 received antiviral treatment, probiotics, antibiotics, and systematic corticosteroids. Antiviral treatment IFN-α2b and corticosteroids to these patients in our study showed a benefit for patients with COVID-19.

It is worth to point out the role of pharmacists in the care of COVID-19 patients. Many drugs are used off-label, and pharmacists can assist in evaluating the efficacy and safety of these drugs and to monitor adverse drug reactions. Pharmacists should warn physicians about any interactions between TCMs and Western medicines when these drugs are prescribed [19, 20]. The limitation of our study was the small sample size. Therefore, the generalizability of the study findings might be limited.

Conclusion

The symptoms of patients in this study are relatively mild compared to the patients initially infected in Wuhan. We observed some treatment benefits with IFN-α2b and corticosteroid therapies but not with novaferon and antibiotic treatment in our study population. Larger sample size studies are needed to validate these findings in future studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Dr. Shusen Sun, PharmD, from Western New England University College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, for the review and critique of the manuscript.

Funding

Changsha Science and Technology Project (No. 202003).

Conflicts of interests

None declared.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qiong Huang and Xuanyu Deng have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Gefei He, Email: 326366726@qq.com.

Zhicheng Gong, Email: gongzhicheng@csu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J MED VIROL 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Hui DS, Azhar EI, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health: the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan S, Siddique R, Shereen MA, Ali A, Liu J, Bai Q, et al. The emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), their biology and therapeutic options. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e00187–e00120. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00187-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report-73. 2th April 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200402-sitrep-73-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=5ae25bc7_2.

- 7.Xu XW, Wu XX, Jiang XG, Xu KJ, Ying LJ, Ma CL, et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;368:m606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song Y, Yao C, Yao Y, Han H, Zhao X, Yu K, et al. XueBiJing injection versus placebo for critically Ill patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(9):e735–e743. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan. China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang Lin M, Wei L, Xie L, Zhu G, Dela Cruz CS, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infections involving 13 patients outside Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1092–1093. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qazi NA, Morlese JF, Pozniak AL. Lopinavir/ritonavir (ABT-378/r) Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002;3(3):315–327. doi: 10.1517/14656566.3.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao B, Wang YM, Wen DN, Liu W, Wang JL, Fan GH, et al. A trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Falzarano D, de Wit E, Rasmussen AL, Feldmann F, Okumura A, Scott DP, et al. Treatment with interferon-alpha2b and ribavirin improves outcome in MERS-CoV-infected rhesus macaques. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/nm.3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin H, Huang L, Zhou J, Lin K, Wang H, Xue X, et al. Efficacy and safety of interferon-alpha2b spray in the treatment of hand, foot, and mouth disease: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial. Arch Virol. 2016;161(11):3073–3080. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan YB. Creatine kinase in cell cycle regulation and cancer. Amino Acids. 2016;48(8):1775–1784. doi: 10.1007/s00726-016-2217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li M, Rao C, Pei D, Wang L, Li Y, Gao K, et al. Novaferon, a novel recombinant protein produced by DNA-shuffling of IFN-alpha, shows antitumor effect in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Cell Int. 2014;14(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-14-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Lu P, Tang M, Hu Q, Polidoro JP, Sun S, et al. Providing pharmacy services during the coronavirus pandemic. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01017-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng L, Qiu F, Sun S. Providing pharmacy services at cabin hospitals at the coronavirus epicenter in China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01020-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.