Abstract

Purpose

This study describes the rapid implementation of telemedicine within an adolescent and young adult (AYA) medicine clinic in response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. While there are no practice guidelines specific to AYA telemedicine, observations made during this implementation can highlight challenges encountered and suggest solutions to some of these challenges.

Methods

Over the course of several weeks in March, 2020, the Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine Clinic at the University of California San Francisco rapidly replaced most in-person visits with telemedicine visits. This required logistical problem-solving, collaboration of all clinic staff members, and continuous reassessment of clinical practices. This article describes observations made during these processes.

Results

Telemedicine visits increased from zero to 97% of patient encounters in one month. The number of visits per month was comparable with that one year prior. While there were limitations to the clinic’s ability to carry out health supervision visits, many general health, mental health, reproductive health, eating disorders, and addiction treatment services were implemented via telemedicine. Providers identified creative solutions for challenges that arose to managing general confidentiality issues as well as specific challenges related to mental health, reproductive health, eating disorders, and addiction care. Opportunities to implement and expand high-quality AYA telemedicine were also identified.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic is leading to widespread telemedicine implementation. While telemedicine seems to be feasible and acceptable for our clinic patients, unanswered questions remain regarding confidentiality, quality of care, and health disparities. Clinical guidelines are also needed to guide best practices for telemedicine in this patient population.

Keywords: Adolescent health services, Adolescent, Telemedicine, Adolescent medicine, Feeding and eating disorders, Addiction medicine, Reproductive health services

Implications and Contributions.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine use is increasing without practice guidelines specific to adolescent health. This study summarizes obstacles to the implementation of telemedicine for adolescents and proposed solutions. Observations made during this process have implications for the continued use of telemedicine to improve health-care access beyond the current pandemic.

See Related Editorial on p.145

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a rapidly evolving public health crisis. Uptake of telemedicine has been one response used by providers to continue caring for patients while minimizing risk of exposure or transmission of COVID-19 [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services defines telemedicine as two-way, live communication between the patient and provider at a distant site including audio and video equipment [5]. This may occur with or without the assistance of peripheral medical examination devices (e.g., electronic stethoscope) and can augment but should not fully replace in-person medical visits [6,7]. Telemedicine has been increasingly recognized in recent years as a tool to improve access to health care [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. Despite successful expansion of telemedicine in some areas, persistent barriers to widespread implementation include patient and provider acceptance, technical connectivity challenges, infrastructure to support Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant care, and unavoidable deviations from clinical standards of care [7]. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged clinicians to rapidly determine how to provide high-quality care while addressing the public health needs of the community. The appropriate response may vary by patient population, specialty, practice setting, and local availability of resources. For providers caring for adolescents and young adults (AYAs), the scramble to care for this vulnerable population in the midst of a pandemic raises questions about quality of care, limitations of telemedicine, and challenges with confidentiality that are yet to be fully understood.

Despite opportunities for improved access to care, telemedicine has not been widely implemented or studied within the field of adolescent medicine. Telemedicine practice guidelines are established for general pediatrics [12] and adolescent and pediatric mental health care, [13] but there are no telemedicine guidelines specific to adolescent medicine. Ethical and legal complexities remain, including concerns over privacy and data security, inequity in access to technology and technological knowledge, and questions regarding effects on the doctor-patient relationship [7,14,15]. Given this population’s unique access-to-care issues (e.g., sexual/reproductive health, mental health, and substance use) and the wide developmental variation in health-care needs and literacy, additional research and guidelines are needed to incorporate telemedicine into AYA care.

Some precedents do exist for remote provision of key components of adolescent medicine including online platforms for reproductive health services [16,17] and mental health telemedicine for the treatment of eating disorders [18,19]. Telemedicine for medical monitoring in eating disorders care is emerging out of necessity during the COVID-19 pandemic [3].

Despite limited evidence and lack of guidelines for AYA telemedicine, the COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated its rapid adoption in AYA-serving practices. The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine clinic provides primary and subspecialty care to local urban AYAs and specialty care to patients from communities across Northern California. This study reports on our clinic’s rapid transition to audiovisual telemedicine without peripheral devices to decrease the number of in-person clinic visits in response to COVID-19 and describes novel observations, challenges, and opportunities for innovation.

Methods

Clinical context

UCSF’s Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine Clinic is embedded in an urban academic medical center. The clinic was established in 1974 and serves 12- to 26-year-old patients. In 2019, the clinic served 1,715 unique patients over 4,195 clinic visits. Patients are 26% male and 32% publicly insured. The clinic provides full-spectrum interdisciplinary AYA care including primary care for AYAs with complex medical conditions, management of attention and mood disorders, sexual and reproductive health care, eating disorder care, and addiction treatment.

Intervention

In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, our practice sought to maximize AYA access to health care while maintaining social distancing. As a result, we rapidly implemented the use of telemedicine in all aspects of our practice. This required coordination between providers, clinical support staff, and clerical staff (see Table 1 : Personnel Involved in Implementation). All providers were trained to use Zoom (Zoom Video Productions, Inc, San Jose, CA), [20] a HIPAA-compliant audiovisual tool, for telemedicine purposes within one week of our initial faculty meeting on COVID-19 (see Table 2 : Timeline).

Table 1.

Personnel involved in implementation

| Title | Role |

|---|---|

| Providers | |

| Nurse practitioners (NP) Adolescent medicine fellows (MD) Adolescent medicine attending physicians (MD) |

Direct patient care via in-person appointments or telemedicine |

| Clinical support staff | |

| Licensed vocational nurses (LVN) Registered nurses (RN) Medical assistants (MA) |

Triage to telemedicine, in-person visit, or respiratory care clinic Vital sign checks, immunization administration, and point of care testing for in-person visits and to augment telemedicine visits. |

| Clerical support staff | |

| Front desk staff Eating disorder program coordinator |

Scheduling including canceling appointments and rescheduling video visits. Facilitating patient portal enrollment. |

| Other health professionals | |

| Social workers (LCSW) | Coordination of social support services, eating disorder programs, referrals for mental health care, and health insurance advocacy. |

| Registered dietitians (RD) | Dietary counseling for primary care and eating disorder patients and families |

Table 2.

Timeline

| Date | Event or intervention |

|---|---|

| 1/22/2020 | First COVID-19 case confirmed in the United States [21] |

| 2/27/2020 | CDC investigates first confirmed community spread of Sars-CoV-2 in the United States which occurred in California’s Bay Area [22] |

| 3/6/2020 | Initiative to explore the expansion of telemedicine begins at the health center level. |

| Intervention week one: zero telemedicine visits per week in Teen Clinic. | |

| 3/9/2020 | First UCSF primary care pediatrics COVID-19 planning meeting |

| 3/10/2020 | 1-Hour optional training course for pediatric care providers on conducting video visits, supplemented by online training videos |

| 3/11/2020 | First UCSF AYA faculty meeting to plan COVID-19 response and transition to telemedicine for AYA Clinic. |

| 3/12/2020 | All hands meeting of clinical faculty and staff across primary care pediatrics with training in UCSF’s telemedicine platform. |

| 3/13/2020 | Plan for near-total transition to telemedicine disseminated and revised by faculty and advanced practice nurses with discussion of expected limitations of telemedicine and a plan for weekly or biweekly evaluation of clinic protocols for all clinical services. Meeting between AYA clinic leadership and hospital nutrition leadership to establish a plan for telemedicine involvement of registered dietitians. First UCSF-wide weekly town hall to disseminate regional and intuitional plans and update campus on current and projected clinical demands. |

| 3/13/2020 to present | Brief daily division leadership phone calls and weekly calls with MDs and NPs are implemented to facilitate rapid and responsive changes to the clinical services. |

| Intervention week two: 56 telemedicine visits per week in Teen Clinic. | |

| 3/16/2020 | All attending physicians, fellows, and nurse practitioners in the practice are telemedicine trained and ready. Daily telemedicine sessions begin for urgent care, mental health (e.g., depression and anxiety assessments, medication management), eating disorder, and addiction treatment follow-up with established patients. Telemedicine clinics are augmented by daily two-hour in-person clinic sessions or nurse-only visits for vital sign checks and laboratory work for select patients. |

| 3/17/2020 | Six Bay area counties become the first region in the nation to mandate inhabitants “shelter in place,” closing schools and nonessential businesses, and banning all nonessential travel [23]. Addiction treatment program: first buprenorphine follow-up visit via telemedicine with established patient with OUD. |

| Intervention week three: 44 telemedicine visits per week in Teen Clinic. | |

| 3/23/2020 | Clinicians continue to meet weekly to discuss challenging cases, creative problem-solving strategies, and plans for expanding telemedicine to a wider range of health concerns and visit types. |

| 3/24/2020 | Addiction Treatment Program: first addiction psychiatry intake via telemedicine with an established patient. |

| 3/25/2020 | Daily team huddles begin with the clinical staff, clerical staff, and one of the practices attending physicians to allow for rapid problem solving and clear communication between clinic providers and staff. |

| Intervention week four: 80 telemedicine visits per week in Teen Clinic. | |

| 3/30/2020 | Department of Health and Human Services announces that it will not enforce rules against using HIPAA noncompliant video chat software for telemedicine visits [24]. CMS modifies its payment policies to encourage telemedicine or telephone encounters [25]. Clinic’s daily telemedicine sessions continue with additional provider schedules added to meet demand. Two-hour in-person clinic sessions scaled back from 5 days per week to 3 days a week because of low patient demand. Addiction Treatment Program: first new patient intake via telemedicine (non-OUD). |

| 3/31/2020 | DEA and SAMHSA issue guidelines allowing credentialed providers to treat new patients with OUD initiate buprenorphine using telemedicine [26]. |

| 4/3/2020 | California’s Governor Gavin Newsom releases an executive order to allow providers to use video chat services to deliver health care without risk of penalty in alignment with the federal Department of Health and Human Services guidelines [27]. |

| 4/6/2020 | Addiction Treatment Program: first new patient intake via telemedicine for patient with OUD |

AYA = adolescents and young adults; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; DEA = Drug Enforcement Administration; HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; MD = physician; NP = nurse practitioners; OUD = opioid use disorder; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; UCSF = University of California San Francisco.

Nursing and administrative staff created new protocols for remote triage, scheduling, and patient check-in. Because virtual visits required patients to have access to the electronic medical record (EMR) patient portal, clerical staff had to develop new workflows to be able to enroll minors and their proxies remotely while still maintaining confidentiality and obtaining appropriate written permissions. A member of the clinical faculty met with support staff daily throughout telemedicine implementation to identify challenges and facilitate communication between providers and staff. The first two weeks of the intervention focused on addressing logistical challenges to EMR patient portal enrollment, patient scheduling, utilization of the telemedicine platform, and streamlining communication between providers, clinical support staff, and clerical support staff. By week two, providers began identifying challenges and lessons learned in practicing telemedicine for general adolescent health care, reproductive health, eating disorders, and addiction treatment as highlighted below. We received a letter of exemption from the UCSF Institutional Review Board for this publication.

Results

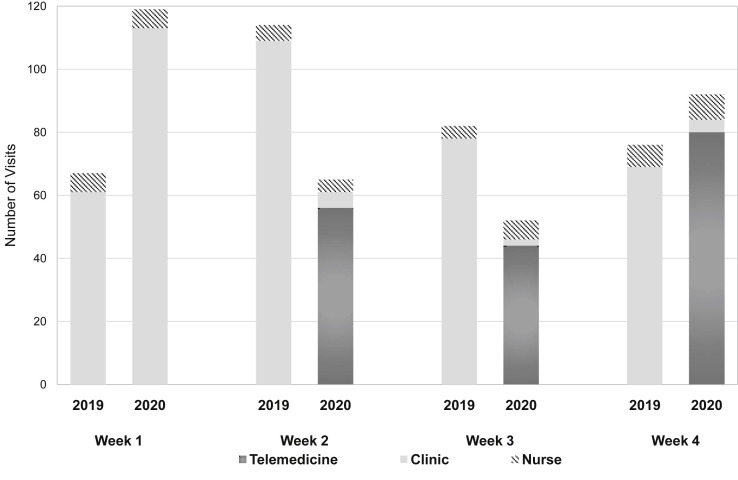

The number of telemedicine visits in our practice increased from zero to 80 per week as of March 30, 2020 (Figure 1 ). While the percentage of provider telemedicine visits increased from 0% to 97%, the number of overall clinic visits did not decline when compared with that one year before (337 visits in March 2019 vs. 332 visits in March 2020), and no-show rates were comparable. The clinic billed 518 relative value units in March 2020, compared with 480 relative value units billed in March 2019. Owing to delays in insurance company adjudications, we cannot report actual March 2020 revenue generated.

Figure 1.

Clinic visits per week. AYA clinic visit types (telemedicine visit, provider visit in clinic, or nurse-only visit in clinic) by week in March 2019 compared to March 2020, illustrating telemedicine visits from zero per week to 56 per week by the second week of March this year. By the last week in March, more visits were conducted via telemedicine than total clinic visits in the same week one year earlier.

Overall, providers noted that telemedicine seemed acceptable to AYAs who generally had competence with electronic communications platforms and welcomed the convenience of meeting with providers remotely. Providers reported only two visits that were not completed because of technical issues. When needed, providers were able to integrate certified medical interpreters directly into telemedicine visits. Generally, patients arrived on time, and the structure of telemedicine encounters combined with our initial problem-focused visits led to timely clinic sessions which were well received by providers and patients.

Providers identified several common barriers to telemedicine across all clinical domains. In some cases, privacy and confidentiality were challenges given the provider’s inability to establish a quiet and private environment for the patient as they would in an office visit. In response, providers encouraged AYAs to use headphones, used yes/no questions, and leveraged the Zoom chat function to allow patients to type replies to questions while limiting disclosure to household members in close proximity. With these interventions, providers only reported seven appointments in which the scope of care was overtly limited because of patient privacy concerns. Lower socioeconomic status compounded privacy challenges because of crowded living conditions. While some providers were also concerned that patients with limited socioeconomic means might not have access to the electronic devices needed for telemedicine (smart phone, tablet, or computer), all patients in our clinic were able to access an appropriate device for their appointments.

Implementation efforts also revealed barriers to telemedicine related to limited provider comfort with clinical decision-making in the absence of a complete physical examination or laboratory data. Providers explored evidence-based practices for treating common ailments such as suspected uncomplicated urinary tract infections or strep throat with clinical scoring and assessment methods based on limited objective data. In addition, numerous providers reported discomfort with asking patients to provide on-camera views of certain body parts as part of their physical examination because of limitations in patient privacy as well as provider-perceived impropriety (see Reproductive health section).

In addition to these overarching issues, the practice also identified actual and potential barriers to telemedicine (Tables 3 and 4 , respectively) and solutions specific to each of its main clinical domains.

Table 3.

Identified telemedicine barriers and solutions

| Barriers | Solutions |

|---|---|

| General issues | |

| Limits to patient privacy and confidentiality |

|

| Limited provider comfort with sensitive examinations on telemedicine |

|

| Limited provider comfort with clinical decision-making in the absence of physical examinations and point-of-care testing. |

|

| Inability to assess recommended anthropomorphic data for annual preventive visits |

|

| Clinical encounters no longer colocated with interdisciplinary colleagues |

|

| Mental health | |

| Need for ongoing screening and assessments of mood symptoms. |

|

| Reproductive health | |

| Limited provider comfort with sensitive examinations on telemedicine |

|

| Need for in-person encounters for LARCs, Papanicolau smears, and acute pelvic complaints |

|

| Eating disorder care | |

| Inability to assess recommended anthropomorphic data for eating disorder visits |

|

| Inability to assure parent privacy while disclosing patient weight or dietary recommendations. |

|

EMR = electronic medical record; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7; LARC = long-acting reversible contraception; PCP = primary care provider; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Table 4.

Anticipated barriers and identified opportunities

| Anticipated barriers | Future opportunities |

|---|---|

| Patients might not have an appropriate device to engage in telemedicine |

|

| Technology literacy gap within a family may lead to decreased engagement with caregiver (e.g., an adolescent may be comfortable with telemedicine, but the parent is not) |

|

| Patients may reject telemedicine because of lack of connection with providers or limits of care. |

|

| Language barriers could limit engagement in telemedicine |

|

| Reimbursements may be low or unavailable for telemedicine |

|

General adolescent and young adult health care

Our initial rollout of telemedicine focused on general AYA acute health complaints that did not require respiratory triage for COVID-19 evaluation. Issues that were particularly straight forward to treat via telemedicine included follow-up for established problems such as chronic headaches, dermatologic issues, and some musculoskeletal complaints. Initially, we did not offer well care visits because of our inability to monitor height, weight, blood pressure, vision, and hearing as recommended by Bright Futures, although we later established a protocol for obtaining at-home weights for those patients with a scale [28]. In addition, vaccines and screening for HIV, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and dyslipidemia could only be completed in person with the help of nurses or phlebotomists. However, many aspects of adolescent and young adult care recommended by Bright Futures were possible to implement via telemedicine including screening for depression, substance use, psycho-social development, and general anticipatory guidance [28].

Another limitation of our initial telemedicine rollout was that our social workers and dietitians were not available in real-time as they had been in the clinic’s former practice model. Telemedicine visits began with one registered dietitian. An additional dietitian and social worker were included by the second week of implementation. To facilitate internal referrals, we created a shared list of patients requiring consultation with these providers in the EMR. Ongoing efforts aim to further integrate our social work and dietitian colleagues into our telemedicine practice.

Mental health

Providers identified that medical management of mood disorders and maintenance of attention deficit hyperactivity medications were all easily managed via telemedicine. We used built-in EMR questionnaires, including the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7, which patients could complete before their appointments to screen for and monitor mood or anxiety disorders. The rapid implementation of telemedicine for mental health services was critical as we saw an influx of college-aged youth returning home abruptly from campuses and requiring mental health support and medication refills because of loss of college-based providers or new onset of acute stress responses secondary to the pandemic. One challenge providers faced was how to appropriately manage medications for conditions typically managed by psychiatrists (e.g., antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines). We chose to bridge patients with prescriptions as we facilitated appropriate local referrals.

Reproductive health

Despite limitations to physical examinations via telemedicine, providers identified contraception counseling and provision of combined hormonal contraceptives (pills, patches, and vaginal rings) as feasible for telemedicine with a plan to reassess blood pressure at the patients’ next in-person clinic visit given the low occurrence of clinically significant hypertension with these methods. In addition, consults for dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and oligomenorrhea were completed via telemedicine with supporting visits for blood work or imaging as indicated. Specific to reproductive health, providers expressed concern about the possibility of reproductive coercion given limitations to patient privacy via telemedicine.

Despite the ease of telemedicine for some contraception visits, many other reproductive health issues required physical examinations (e.g., suspicion for pelvic inflammatory disease) or laboratory tests (e.g., STI screening, testing, and treatment; HIV screening and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis). Likewise, in-person visits are essential to the provision of long-acting reversible contraception (intrauterine devices and the implant), injectable medroxyprogesterone, treatment of ascending pelvic infections, and Papanicolaou smears. Patients requiring these services were offered appointments during the clinic’s abbreviated in-person sessions. We also transitioned collection of pregnancy tests, STI screening, HIV testing, and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis monitoring serologic tests to nursing or laboratory visits either at UCSF or commercial laboratories.

In some cases, when physical examinations for reproductive health complaints were possible via telemedicine, providers in our practice struggled with the propriety of virtual genital or breast examinations. For example, one patient described a classic genital herpetic lesion by history, but the provider did not feel it was appropriate to ask the patient to point his camera at the lesion and instead asked the patient to come to clinic for an in-person visit. Other providers chose to complete similar examinations via telemedicine or ask patients to submit photos of their lesions via the EMR patient portal.

Eating disorders

The medical monitoring of eating disorders includes regular assessment of weight, vital signs, dietary history, electrolyte monitoring, and coordination with the patients psychotherapist [29]. Given the need for regular anthropomorphic measurements for these patients, providers expressed particular concern about transitioning these patients to telemedicine. As such, we collaborated with our psychiatry colleagues to refine a protocol for family members to calibrate home scales and take blind weights before telemedicine visits. In other cases, therapists or primary care providers measured weights and vital signs and forwarded these data to our team. Finally, when a patient was clearly engaged in concerning behaviors (e.g., increased restricting, purging, over exercising) or the provider, therapist, patient, or family member had a high index of suspicion for medical deterioration, the patient was asked to come in for one of the clinic’s limited in-person sessions for measurement of weight, orthostatic vital signs, and any indicated blood work (e.g., electrolyte monitoring). When admission was required due to vital sign instability, it could be coordinated from that visit.

Providers noted that our eating disorder patients particularly benefitted from the convenience of telemedicine as they are referred to our clinic from a much wider geographic range than our primary care patients. By working with our hospital’s satellite clinics, local primary care providers, and therapists, we were able to spare these patients and their families the financial and time burdens of travel to our clinic, in addition to minimizing potential transmission of COVID-19 between communities.

Our providers identified unique challenges to telemedicine in this patient population. Concerns about privacy arose again, including concerns of patient distress related to overhearing specific weight numbers or nutrition interventions that providers would otherwise discuss confidentially with parents or guardians in an in-person clinical setting. Providers encouraged parents to use headphones in these encounters. Conversely, telemedicine created flexibility for some families, allowing increased parental participation in medical visits (e.g., among parents with separate households or for working parents).

Addiction treatment

The UCSF Youth Outpatient Substance Use Program is embedded in the Adolescent & Young Adult Medicine Clinic and provides treatment to youth with opioid use disorder (OUD) and other substance use disorders. Initially, we limited these telemedicine visits to established patients. We expanded care to new patients after March 31, 2020, when the Drug Enforcement Administration in partnership with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration issued guidelines allowing appropriately-credentialed providers to admit and treat new patients with OUD and to prescribe buprenorphine using telemedicine platforms without initial in-person assessments during the COVID-19 public health emergency [26]. As a program funded by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Youth Outpatient Substance Use Program is legally required to complete structured intakes that include demographic, diagnostic, physical health, and mental health information [30]. To ensure that new patients completed federally required intake interviews, our program support staff began conducting these via Zoom© before each patient’s first physician telemedicine visit. We asked that, whenever possible, youth and their parents log in to visits from different devices or have access to separate private spaces to facilitate separate but co-occurring confidential meetings with clinicians and social workers. For youth in need of psychiatric assessments for comorbid disorders, our providers also transitioned to telepsychiatry. As most components of the clinical opiate withdrawal scale can be assessed via video connection, we plan to conduct buprenorphine inductions using telemedicine for youth who can enlist a loved one to provide support. We will offer in-clinic inductions to youth who do not have access to a support person.

Discussion

This study describes one AYA medicine practice’s experiences in quickly implementing telemedicine without peripheral examination devices in response to a pandemic. Many observations are widely applicable to other AYA medicine practices, while some may be unique to our group. Because our practice is based in San Francisco, where strict shelter-in-place mandates were announced early in the COVID-19 pandemic (March 16, 2020), [31] we adopted changes in our practice earlier and more rapidly than many other practices in the United States. This rapid shift required us to continuously reassess balancing adherence to social distancing while preserving our commitment to high-quality AYA care. Given the dearth of telemedicine guidelines specific to AYA, these changes were uncomfortable for our providers but necessary in the face of unprecedented circumstances.

Our rapid transformation to a primarily telemedicine practice was facilitated by multiple factors including institutional support for telemedicine as well as access to the necessary technology and training for providers and clerical staff in their adjusted roles. Not all AYA practices have the same systems-level supports in place, and different creative strategies will be required to resolve barriers to telemedicine.

State and national policies regarding telemedicine are undergoing rapid changes. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has modified payment policies to encourage telemedicine [24], and private payors are following suit, announcing elimination of copayments for telemedicine visits [25]. While payment and privacy laws vary by state, many states have reduced policy barriers to telemedicine [32]. Similarly, the Department of Health and Human Services announced that it will not penalize the use of HIPAA noncompliant video chat applications for telemedicine during the COVID-19 emergency [33]. In other countries, telemedicine implementation is also being fast-tracked with adjustments to privacy laws and systems-level supports [2]. While expansion of AYA telemedicine continues under these emergency policy changes, it is unclear if this expansion would be sustainable should these be reversed. For example, practices may no longer be able to effectively bill for telemedicine, clinicians currently using HIPAA noncompliant applications may need systems-level supports to transition to different platforms, and addiction medicine providers may no longer be able to prescribe medications for treatment of OUD using only telemedicine.

Serving AYAs through telemedicine poses many unanswered questions. For AYA primary care, the extent to which health supervision via telemedicine is appropriate remains unclear. While many aspects of routine AYA preventive care can be done via telemedicine, some components are not feasible [28]. It remains to be seen how advancing technologies (e.g., wearables or smart phone accessories) and the shifting culture of adolescent medicine might overcome some of these challenges. A lack of research or practice guidelines on telemedicine for AYAs leaves providers in this field with patients who largely have access to the necessary technology [34] and are likely eager to take advantage of virtual visits [35] but with no clear evidence or recommendations on applying telemedicine in this population. This study was limited to anecdotal provider experiences and short-term data. More research is needed to understand the patient and family experience of AYA telemedicine.

Along with the possibilities offered by telemedicine, it is crucial to consider its current limitations and how they can be addressed. Barriers to telemedicine still exist for AYAs who lack access to internet or required technology or who have no private place to conduct a visit (e.g., due to homelessness or overcrowding). In addition, it is well documented that young adults have worse clinical outcomes than adolescents on a variety of health issues, and it remains to be seen if telemedicine may impact these disparities [36]. Furthermore, as we push the limits of what can be done via telemedicine, our patients’ safety must remain paramount. For example, AYAs may live in unsafe conditions involving abuse or violence, where discussions during a telemedicine visit at home could put them in danger or they may not be able to safely disclose all their concerns. In-person clinic visits must remain available for patients, and providers should use in-person appointments if they suspect telemedicine may be inappropriate for these reasons.

As noted, our providers struggled with the propriety of genital examinations via telemedicine. Strategies for collaborative decision-making with patients about limitations of telemedicine examinations balanced with patient inconvenience and risk (e.g., risk of infection in the COVID-19 pandemic) will need to be explored through further research with patients and providers. Best practices in this regard are also likely to have implications for sexual maturity ratings for adolescent preventative health-care visits.

There is particularly urgent need to better understand the efficacy of telemedicine for the medical management of patients with eating disorders and addiction. While telemedicine has the potential to expand access to specialty care for both, research is needed to understand the safety, efficacy, and acceptability of telemedicine for these disorders. For eating disorder care, research is needed to assess the accuracy of home weights, hospitalization rates, and long-term recovery outcomes when eating disorders are managed via telemedicine. AYA subspecialists can expand access to care by collaborating with primary care providers via teleconsultation [7].

There is a sense that many of the changes that we have described here are not just temporary responses, but rather they represent a “new normal.” While we are by no means proposing that telemedicine for AYAs will replace seeing patients in person, the field can look at this quick shift to telemedicine as an opportunity to reach our patient population in new ways, both in this time of crisis and beyond.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their colleagues in the UCSF Adolescent and Young Adult clinic including the administrative staff, clerical staff, and clinical staff, and especially our lead registered nurse Maritza Sanchez, who worked tirelessly for weeks to transition our practice to telemedicine. They thank Bradley Crow for his help collecting clinic utilization data. They would also like to thank their dieticians, social worker, physician, and nurse practitioner colleagues in the UCSF Division of Adolescent Medicine for sharing their clinical insights and creative strategies with us. The authors thank their UCSF Psychiatry colleagues, particularly Dr. Erin Accurso, for sharing their eating disorder protocol for home weights and collaborating with the authors closely in the care of their mutual patients during this unprecedented transition. Finally, they thank the Division Chief of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine Dr. Charles Irwin for his advice in development of this article.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

A.B., M.R.-F., and Charles E. Irwin, Jr. were partially supported by Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Services and Resources Administration, USDHHS LEAH Grant T71MC0003. M.R.-F. was partially supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Development (K23-HD093839-01) and the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Watson Scholars Program. Dr. Charles E. Irwin Jr. was also partially supported by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Services and Resources Administration, USDHHS (cooperative agreements U45MC27709 and UA6MC27378). S.B. was partially supported by NIH/NCI Grant R01CA247705 The UCSF Youth Outpatient Substance Use Program and V.M. were partially supported by a federal grant under the State Opioid Response program, with funding provided by the California Department of Health Care Services.

References

- 1.Keesara S., Jonas A., Schulman K. Covid-19 and health Care’s Digital Revolution. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Telemedicine Arrives in the U.K.: ‘10 Years of change in one Week.’ the New York times. www.nytimes.com/2020/04/04/world/europe/telemedicine-uk-coronavirus.html Available at:

- 3.Davis C., Chong N.K., Oh J.Y. Caring for children and adolescents with eating disorders in the current COVID-19 pandemic: A Singapore perspective. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S., Yang L., Zhang C. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telemedicine. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/telemedicine/index.html Medicaid.gov Available at:

- 6.Weinstein R.S., Krupinski E.A., Doarn C.R. Clinical examination component of telemedicine, telehealth, mHealth, and connected health medical practices. Med Clin North America. 2018;102:533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke B.L., Hall R.W., The Section on telehealth care Telemedicine: Pediatric applications. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e293–e308. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcin J.P., Shaikh U., Steinhorn R.H. Addressing health disparities in rural communities using telehealth. Pediatr Res. 2016;79:169–176. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cain S., Sharp S. Telepharmacotherapy for Child and adolescent psychiatric patients. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26:221–228. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armfield N.R., Donovan T., Bensink M.E. The costs and potential savings of telemedicine for acute care neonatal consultation: Preliminary findings. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18:429–433. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.gth101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaikh U., Cole S.L., Marcin J.P. Clinical management and patient outcomes among children and adolescents receiving telemedicine consultations for Obesity. Telemed E-health. 2008;14:434–440. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2007.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McSwain S.D., Bernard J., Burke B.L. American telemedicine Association Operating Procedures for pediatric telehealth. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23:699–706. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers K., Nelson E.-L., Rabinowitz T. American telemedicine Association practice guidelines for Telemental health with children and adolescents. Telemed E-health. 2017;23:779–804. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2017.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langarizadeh M., Moghbeli F., Aliabadi A. Application of Ethics for providing telemedicine services and information technology. Med Arch. 2017;71:351–355. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2017.71.351-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nittari G., Khuman R., Baldoni S. Telemedicine practice: Review of the current Ethical and legal challenges. Telemed E-health. 2020 doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams R., Meredith A., Ott M. Expanding adolescent access to hormonal contraception: An update on over-the-counter, pharmacist prescribing, and web-based telehealth approaches. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:458–464. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel R., Munro H. Standards for online and remote providers of sexual and reproductive health services. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95:315–316. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2019-054130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazdin A.E., Fitzsimmons-Craft E.E., Wilfley D.E. Addressing critical gaps in the treatment of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50:170–189. doi: 10.1002/eat.22670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson K.E., Byrne C.E., Crosby R.D. Utilizing Telehealth to deliver family-based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50:1235–1238. doi: 10.1002/eat.22759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zoom© . 2020. Zoom Video communications, Inc.www.zoom.us Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cases in U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html Available at:

- 22.New coronavirus cases in California spark fears of wider spread. 2020. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-02-28/intense-search-in-california-for-others-exposed-to-coronavirus-patient Available at:

- 23.San Francisco and San Francisco County Department of Public Health Order of the Health Officer No. C19-07 ; 2020. Accessed 20 May 2020.

- 24.Trump Administration Makes Sweeping Regulatory Changes to Help U.S. Healthcare system Address COVID-19 patient Surge. CMS; 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-makes-sweeping-regulatory-changes-help-us-healthcare-system-address-covid-19 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 25.Augenstein J. Opportunities to expand telehealth Use amid the Coronavirus pandemic. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200315.319008/full Health Affairs. Available at:

- 26.DEA Letter to Qualifying Practitioners. 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/dea-samhsa-buprenorphine-telemedicine.pdf DEA068. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 27.Executive Order N-43-20, Executive Department, State of California; 2020. Accessed 20 May 2020.

- 28.Bright Futures guidelines for health supervision of Infants, Children, and adolescents. 4th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; Itasca, IL: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golden N.H., Katzman D.K., Sawyer S.M. Position paper of the Society for adolescent health and medicine: Medical management of restrictive eating disorders in adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.SAMHSA GPRA measurement tools. https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/gpra-measurement-tools Available at:

- 31.Gajanan M. Time; 2020. What Does ’shelter in place’ mean? Here’s what Life is like under the mandate.https://time.com/5806477/what-is-shelter-in-place/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 32.COVID-19 RELATED STATE ACTIONS. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-related-state-actions CCHP. Available at:

- 33.Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth The office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the Department of health and Human services (HHS) https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html Available at:

- 34.Anderson M., Jiang J. Pew Res cent internet Sci Tech; 2018. Teens, Social Media & technology 2018.https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 35.To W.-M., Lee P.K.C., Lu J. What Motivates Chinese young adults to Use mHealth? Healthcare. 2019;7:156. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7040156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park M.J., Scott J.T., Adams S.H. Adolescent and young adult health in the United States in the Past decade: Little Improvement and young adults remain worse off than adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]