Highlights

-

•

Neurological complications related to SARS-CoV-2 are being reported around the world.

-

•

The more “rare” cases reported, causality and strong conclusions can be established.

-

•

Facial Diplegia and Guillain-Barré Syndrome have been connected to SARS-CoV-2 twice.

Keywords: Guillain Barré Syndrome, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Facial diplegia, Facial nerve palsy

Abstract

We present a case of facial diplegia after 10 days of SARS-CoV-2 confirmed infection symptoms in a 61 year old patient without prior clinically relevant background. There are few known cases of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) related to SARS-CoV-2 infection; we propose this case as a rare variant of GBS in COVID-19 infection context, due to Its chronology, clinical manifestations and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings.

1. Introduction

Several typical and not so typical neurologic late manifestations of viral previous pandemics have been proposed throughout human history, for example, with never fully certain causality, there is encephalitis lethargica and its relationship with the influenza pandemic of 1918 [1]. SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is spreading in an era of scientific advances that offers medical community higher chances of establishing causal relationships and common efforts to fight disease and sequelae.

Patients with several neurological involvement due to SARS-CoV-2 infection have been described in the recent outbreak in China [2]; hitherto, there are few described cases of Guillain Barré and SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1 ). More cases are foreseen due to the virus pathogenesis and epidemiology [3].

Table 1.

Reported Guillain Barré Syndrome cases related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, demografic characteristics and country.

| Sex and age† | F – 77 M – 23 M – 55 M – 76 M – 61 |

F – 76 | M – 64 | M – 54 | M – 65 | F – 61 | M – 61 |

| Country | Italy | Spain [11] | France [12] | USA [13] | Iran [14] | China [15] | Spain* |

F: Female, M: Male.

Juliao Caamaño, Alonso-Beato, in this publication.

Coronaviruses can cause nervous tissue injuries through several known mechanisms (direct infection injury, hypoxia, ACE2 receptors, immune injury [2]; immunomodulatory treatment and gut microbial translocation) [4]. In a series of 214 patients, Mao et al. reported dizziness, headache, hypogeusia and hyposmia as the most common CNS and PNS manifestations [5]. GB is not yet considered a common complication.

2. Case presentation

A 61 year old patient had fever and coughing without dyspnea on day 1 of the illness; after telephone contact with his primary care physician, chest plate and nasopharyngeal sampling RT-PCR, He was diagnosed and treated as a SARS-CoV-2 infection with pneumonia (hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/Ritonavir for 14 days).

After one week, his symptoms disappeared and on day 10 of his illness, He noted liquid dripping on his right facial commissure and went to the ER. With a diagnosis of right peripheral facial nerve palsy, He was transferred to the low risk COVID19 dedicated hospital and the day after He was transferred back to our ward due to progression towards bilateral facial nerve palsy (Fig. 1 ) with unresponsive blink reflex on both eyes. He had no other neurological findings at examination, including symmetrical and normal force, sensitivity, reflexes, ocular movements and a normal gait.

Fig. 1.

Facial Diplegia on admission. Video on Appendix 1A.

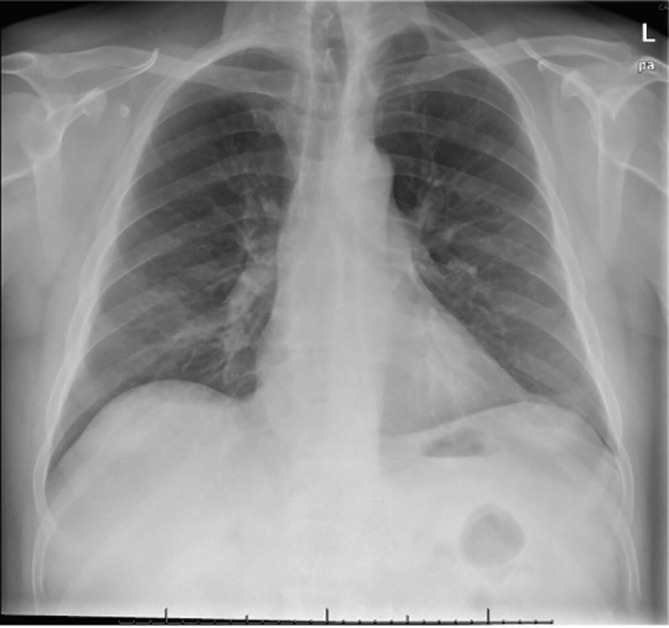

His chest plate showed significant improvement of pneumonia (Fig. 2, Fig. 3 ) and He had no remarkable laboratory findings besides CSF data. Brain CT and MRI were performed without any acute pathological findings and an image guided lumbar puncture demonstrated mildly elevated levels of proteins (44 mg/dL), absent leukocytes and a negative RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 on CSF.

Fig. 2.

Chestplate on admission showing bilateral frosted glass pneumonia.

Fig. 3.

Chestplate 10 days later with notable improvement.

Our patient completed treatment for SARS-CoV-2 adequately and did not present life-threatening signs at any time; He was treated with low dose oral prednisone and after two weeks He started with a barely notable improvement on both sides.

3. Discussion

We regard the patient’s neurological complication as directly related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, considering Its clinical course and absence of other possible causes in later diagnostic testing. According to previously described GBS variants we propose it as a DP, clinically coherent with the diagnostic criteria for DP by Wakerly et al. (2015) [6]; similar features with the series of DP by Suzuki et al. (2009) [7] and resembling a single case from the recent series by Toscano et al. (2020) [8] related with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

GBS is a peripheral nervous system disorder that presents as a rapidly progressive, ascending, flaccid paralysis with diminished or absent reflexes. The disease is often triggered by infectious processes. Campylobacter jejuni infection is the most commonly identified precipitant of GBS. Some viruses like Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and Zika have also been associated with GBS [9].

GBS used to be considered a single entity characterized by lymphocytic inflammation and peripheral nervous system demyelination. Now, It is usually clinically defined as a more diverse disorder divisible into several patterns and with various clinical manifestations. One proposed clinical variant is facial diplegia [10].

According to diagnostic criteria proposed by Wakerly et al. (2015) [6] our case accomplishes bifacial symmetrical weakness, absence of limb, neck or ocular weakness, an antecedent of prior infectious disease in the previous 3 days to 6 weeks and albuminocytological dissociation in CSF. We hypothesize that SARS-CoV-2 infection might have triggered this atypical clinical variant of GBS in our patient.

Some other case reports (Table 1) have been published relating typical variants of GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection so we suggest a possible association between them, but more cases are needed to support causality. The absence of anti ganglioside antibodies testing available data is a limiting factor in comparing these cases.

4. Conclusion

There is a clear emerging group of neurological manifestations during and after SARS-CoV-2 infection; some directly linked, others not so much. The relationship between viral infections and GBS with a consistent chronological sequence is widely accepted. As in previous human pandemics; We are facing unknown possible complications of an extensively expressed disease; according to clinical resemblance with other reports and coherence with diagnostic criteria, our case is a highly probable GBS DP variant. More similar cases are needed to establish confident causality and only time will let us know more about this phenomenon.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.016.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cheyette S.R., Cummings J.L. Encephalitis lethargica: lessons for contemporary neuropsychiatry. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7(2):125–134. doi: 10.1176/jnp.7.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Y., Xu X., Chen Z., Duan J., Hashimoto K., Yang L. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun [Internet] 2020;(March):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matías-Guiu J., Gómez-Pinedo U., Montero-Escribano P., Gómez-Iglesias P., Porta-Etessam J., Matías-Guiu J.A. ¿Es esperable que haya cuadros neurológicos por la pandemia de SARS2-CoV? Neurología. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troyer E.A., Kohn J.N., Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao L., Wang M., Chen S., He Q., Chang J., Hong C. Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series Study. SSRN Electron J. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wakerley B.R., Yuki N. Isolated facial diplegia in Guillain-Barré syndrome: bifacial weakness with paresthesias. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52(6):927–932. doi: 10.1002/mus.24887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Susuki K., Koga M., Hirata K., Isogai E., Yuki N. A Guillain-Barré syndrome variant with prominent facial diplegia. J Neurol. 2009;256(11):1899–1905. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toscano G., Palmerini F., Ravaglia S., Ruiz L., Invernizzi P., Cuzzoni M. Guillain-Barré Syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimachkie M, Barohn R. Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Variants. Neurologic Clinics. 2013;31(2):491–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziganshin R, Ivanova O, Lomakin Y, Belogurov A, Kovalchuk S, Azarkin I. The Pathogenesis of the Demyelinating Form of Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS): Proteo-peptidomic and Immunological Profiling of Physiological Fluids. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2016;15(7):2366–2378. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.056036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marta-Enguita J., Rubio-Baines I., Gastón-Zubimendi I. Síndrome de Guillain-Barré fatal tras infección por virus SARS-CoV2. Neurología. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camdessanche J., Morel J., Pozzetto B., Paul S., Tholance Y., Botelho-Nevers E. COVID-19 may induce Guillain-Barré syndrome. Rev Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virani A., Rabold E., Hanson T., Haag A., Elrufay R., Cheema T. Guillain-Barré Syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. IDCases. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sedaghat Z., Karimi N. Guillain Barre syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: a case report. J Clin Neurosci [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao H., Shen D., Zhou H., Liu J., Chen S. Correspondence. Lancet Glob Health [Internet] 2020;4422(20):2–3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.