Abstract

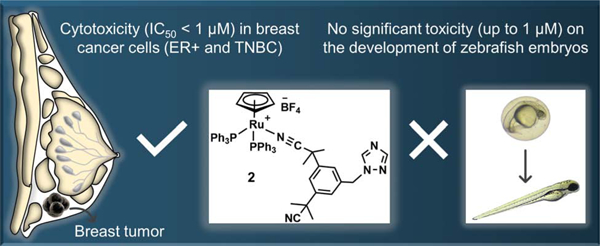

Ruthenium-based complexes currently attract great attention as they hold promise to replace platinum-based drugs as a first line cancer treatment. Whereas ruthenium arene complexes are some of the most studied species for their potential anticancer properties, other types of ruthenium complexes have been overlooked for this purpose. Here, we report the synthesis and characterization of Ru(II) cyclopentadienyl (Cp), Ru(II) cyclooctadienyl (COD) and Ru(III) complexes bearing anastrozole or letrozole ligands, third-generation aromatase inhibitors currently used to treat estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer. Among these complexes, Ru(II)Cp 2 was the only species found to be stable in DMSO and in cell culture media and as a result, the only complex for which the in vitro and in vivo biological activities were investigated. Unlike anastrozole alone, complex 2 was considerably cytotoxic in vitro (IC50 values < 1μM) in human ER+ breast cancer (T47D and MCF7), triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) (MBA-MB-231), as well as in aggressive (H295R) adrenocortical cells. Theoretical (docking simulation) and experimental (aromatase catalytic activity) studies suggested that an interaction between 2 and the aromatase enzyme was not likely to occur and that the bulkiness of the PPh3 ligands could be an important factor preventing the complex to reach the active site of the enzyme. Exposure of zebrafish embryos to complex 2 at concentrations around its IC50 in vitro cytotoxicity value (0.1–1 μM) did not lead to noticeable signs of toxicity over 96h, making it a suitable candidate for further in vivo investigations. This study confirms the potential of Ru(II)Cp complexes for breasts cancer therapy, more specifically against TNBCs that are usually not responsive to currently used chemotherapeutic agents.

Keywords: ruthenium complex, breast cancer therapy, estrogen receptor positive breast cancer, triple negative breast cancer, aromatase inhibitor, zebrafish

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Metal complexes are a useful class of molecules with a broad spectrum of therapeutic applications. Despite the considerable success of platinum-based anticancer agents, which are administered to almost 50% of patients undergoing chemotherapy, factors such as severe side effects and emergence of cancer cell resistance limit their clinical applications [1–4]. In the past years, ruthenium compounds have attracted increasing attention and are often considered potential alternatives to platinum drugs given their selective bioactivity and their ability to overcome platinum-mediated cancer cell resistance. They are known for their cytotoxicity and/or their antimetastatic properties through distinct mechanisms of action, notably DNA or protein binding, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and cancer cell mobility inhibition [1],[5–7]. Importantly, several ruthenium complexes have entered and/or are currently in various stages of clinical trials [8–15]. Of particular interest is the design of organoruthenium complexes bearing carefully selected biologically active ligands such as enzyme inhibitors involved in the treatment of cancer, allowing the development of efficient drug/prodrug candidates that can display multiple modes of action. This strategy can potentially circumvent emerging drug resistance mechanisms, a common cause of mortality in cancer patients [16–19]. For instance, we reasoned that third-generation aromatase inhibitors such as the nonsteroidal triazole derivatives anastrozole (Arimidex®) and letrozole (Femara®) could be suitable candidates for this purpose, as they are widely used to treat estrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer in postmenopausal women, and have the ability to coordinate ruthenium [20]. ER+ breast cancer cells proliferate under the influence of elevated estrogen levels, but are deprived of this hormone by aromatase inhibitors, which act by preventing the aromatase-catalyzed production of estrogens from androgens [21]. Despite the success of third generation aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of breast cancer, in approximately one third of patients diagnosed with metastatic ER+ breast cancer, therapies involving these drugs lead to the mutation of the ER gene, resulting in a treatment-resistant cancer that is often incurable [22, 23]. Furthermore, estrogen deprivation was previously reported to sensitize ER+ breast cancer cells to cytotoxic agents [24, 25].

We recently reported the biological activity of a series of half-sandwich ruthenium(II)-arene complexes tethering anastrozole ligands [26]. This previous study followed a preliminary investigation by Maysinger et al on the cytotoxicity of a series of ruthenium(II)-arene complexes bearing letrozole [16]. To get more insights into the potential effectiveness of ruthenium-anastrozole complexes in cancer therapy, we were interested in exploring the physical and biological properties of structurally and electronically diverse types of ruthenium complexes. Although half-sandwich ruthenium(II)-arene complexes have been extensively investigated for their ability to induce cancer cell toxicity and, in some cases, with high selectivity toward cancer cells [27–29], there are far fewer studies of the anticancer potential of ruthenium(II) complexes based on cyclooctadiene (COD) or cyclopentadiene (Cp) ligands [30–41]. For instance, Kasper et al reported a cationic Ru(II)COD complex with considerable cytotoxicity in Jurkat leukemia cells, for which the mode of action is believed to be associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [41]. Another report revealed that a series of Ru(II)COD complexes with bidentate N,N-donor ligands had high affinity to human serum albumin (HSA). However, the cytotoxicity of these complexes was not investigated [33]. Promising anticancer activities were also reported for some Ru(II)Cp complexes [34, 42–47]. For instance, it was shown that replacing the arene ligand in the structure of a RAPTA-type complex, [(η6-arene)RuCl2(PTA)] (PTA = 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane), with a bulky cyclopentadienyl electron-donating ligand led to compounds with enhanced cytotoxicities [43, 44]. This effect is believed to be associated with the improved ability of the complexes to cross cancer cell membranes [43]. Notably, Tomaz et al reported a promising Ru(II)Cp complex, TM34, with a significant cytotoxicity in cisplatin resistant cancer cells. Its mode of action is believed to involve interference with DNA repair mechanisms and activation of apoptotic pathways [45]. Florindo et al synthesized and characterized a series of Ru(II)Cp complexes bearing carbohydrates such as glucose and fructose with promising in vitro cytotoxicities against Hela human cervical cancer and HCT116 human colon carcinoma cells [34, 37]. The cytotoxicity of these complexes was found to be significantly influenced by the nature of the carbohydrate moiety and the metal center. Interestingly, iron complexes of the same ligands induced less cytotoxicity in cancer cells compared to the corresponding ruthenium complexes, confirming the importance of the ruthenium metal for the anticancer activity of such metallodrugs [34]. Moreira et al reported Ru(II)Cp complexes with the ability to induce inhibition of proliferation and apoptosis, not only in an estrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer cell line (MCF7), but also in an aggressive triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell line (MDA-MB-231). Compounds were found to interact with mitochondria and with cytoskeleton, and to reduce the colony formation potential of breast cancer cells [46]. Morais et al reported a new family of Ru(II)Cp complexes with O,N and N,N′-heteroaromatic bidentate ligands that revealed an exceptional activity with IC50 values in the nanomolar range against the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line [47]. Mendes et al investigated the in vivo antitumor activity of a Ru(II)Cp (TM90, [Ru(η5-C5H5)(PPh3)(bopy)] [CF3SO3] (bopy = 2-benzoylpyridine) on nude female mice bearing TNBC orthotopic tumors. Importantly, the study revealed the ability of the complex to suppress tumor growth over time [42], to increase the lifetime of mice after surgical removal of the tumor (compared to untreated mice) and to not negatively affect their behavior [42]. It is of high importance that Ru(II)Cp complexes display promising activities for the treatment of TNBC which, in contrast to hormonal receptor positive (HR+) breast cancers, does not respond to hormonal therapy approaches [48, 49]. DNA interaction [30, 35, 39], cell-membrane transporter inhibition [40], human serum albumin (HSA) binding [36] and cell cycle disturbance [39] have been also reported as other possible modes of action for Ru(II)Cp complexes. Ru(III) complexes have also attracted interest due to their cytotoxicity or/and antimetastatic properties alongside their low systemic toxicity [7, 15, 50]. For instance, the ruthenium (III) complex KP1339 did not only show cytotoxicity in different in vivo tumor models (more specifically in colon cancer) in preclinical studies, but was also found to stabilize the disease in clinical studies involving cancer patients while only inducing mild side effects. Disruption of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis and induction of immunogenic cell death (ICD) have been reported as mechanisms of action for this complex [15]. In the present study, we report the synthesis, characterization and stability assessment of Ru(II)COD, Ru(II)Cp, and Ru(III) complexes bearing anastrozole (ATZ) or letrozole (LTZ). Results regarding the in vitro anticancer activity in several human cell lines and in vivo toxicity in a zebrafish model of the most promising candidate is also presented.

Results and discussion

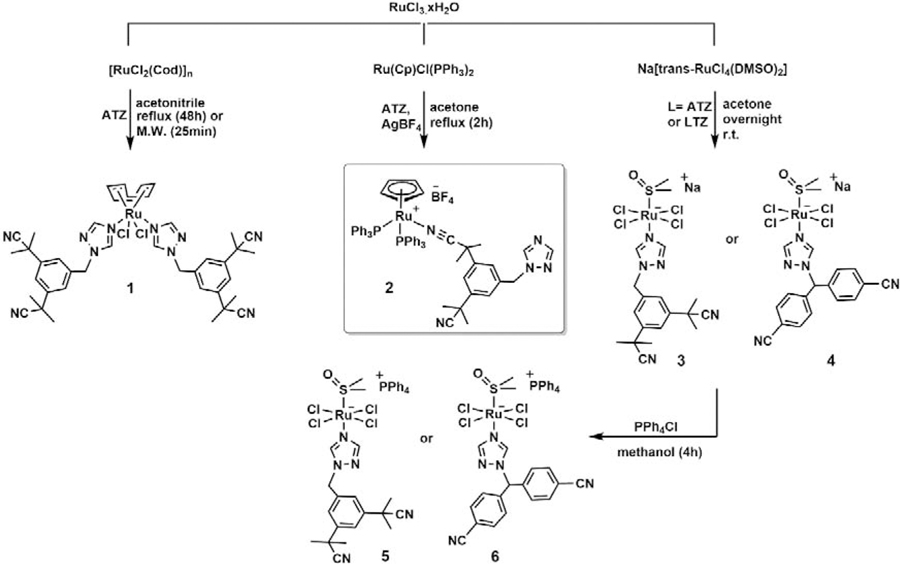

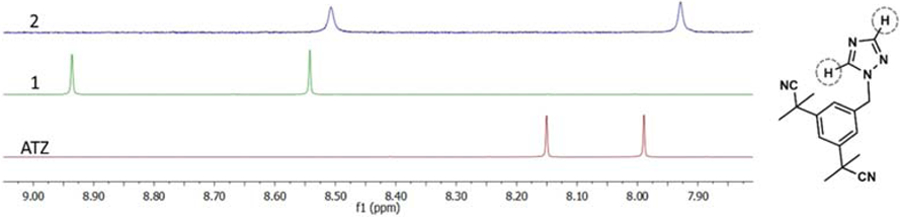

The synthesis of complex 1, RuCOD(ATZ)2Cl2, was first attempted by allowing [Ru(COD)Cl2]n to react with two equivalents of anastrozole in refluxing acetonitrile. No product could be detected after 18h, and only a 13% conversion could be observed after 48h. The yield could be increased up to 22% and the reaction time decreased to 25 min when the reaction was performed in a microwave reactor (15 psi, 200 W, 80 °C) (Scheme 1). It is noteworthy that using the microwave for longer periods of time under the above-mentioned conditions resulted in a significant decrease in the yield of the reaction, possibly due to some interactions of the final product with other molecules present in the reaction mixture. Only few examples of microwave-assisted syntheses of ruthenium complexes were previously reported [51–53]. The synthesis of cationic complex 2, RuCp(PPh3)2(ATZ)BF4, was performed by reacting RuCp(PPh3)2Cl and anastrozole in the presence of AgBF4 in refluxing acetone for 2h (36% yield). Both Ru(II) complexes 1 and 2 are soluble in acetone, alcohols and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) but poorly soluble in water. The anionic Ru(III) species 3, Na[trans-RuCl4ATZ(DMSO)], was also prepared by allowing Na[trans-RuCl4(DMSO)2] to react with anastrozole in acetone overnight at room temperature (56% yield). Keeping in mind that the anticancer properties of metal complexes often vary with their lipophilicity [27, 54], the sodium counterion in the structure of 3 was replaced with a more lipophilic cation. Complex 5, PPh4 [trans-RuCl4ATZ(DMSO)], was then obtained (70% yield) by allowing a methanol solution of compound 3 to react with PPh4Cl for 4 h at room temperature. Although anastrozole and letrozole both belong to the third-generation class of aromatase inhibitors and have closely related structures, their efficacy has been reported to differ in some cases. For instance, letrozole was more effective at lowering estrogen levels than anastrozole in human breast cancer tissue [55, 56]. For comparison purposes, letrozole derivatives of complexes 3 and 5, 4 (66% yield) and 6 (39% yield), were also synthesized using the same reaction conditions. All Ru(III) complexes were soluble in most organic solvents except 6 which had a poor solubility in most solvents. Due to the nature of the counterions, only complexes 3 and 4 were found to be soluble in water. The identity and purity of all complexes were confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (only in the case of diamagnetic species 1 and 2), high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS) and elemental analysis. In contrast to complex 1 and previously reported Ru(II)-arene complexes bearing anastrozole or letrozole [16, 26], signals corresponding to the protons and/or carbons of the anastrozole moiety in the 1H NMR and 13C{1H} NMR spectra of 2 were non-equivalent (phenyl, nitrile and methyl groups), suggesting a different coordination mode of this ligand in this complex. Compared to the downfield chemical shift of 1H NMR signals assigned to the protons of the triazole ring of 1, the corresponding signals in the spectrum of 2 were only slightly shifted in comparison with the ones observed for free anastrozole (Figure 1), suggesting that anastrozole is coordinated to ruthenium via one of its nitrile moieties, which was further confirmed by X-ray crystallography analysis (Figure 2, vide infra). This mode of coordination may be favored due to the steric hindrance of the two bulky triphenylphosphine ligands, preventing the triazole ring from reaching the metal site. As reported for other Ru(II)Cp and Ru(II)COD complexes [30, 57], a singlet peak at 4.51 ppm was observed for the cyclopentadienyl moiety of 2, whereas three signals at 2.06, 2.66, 4.09 ppm were observed for the non-equivalent protons in the cyclooctadienyl moiety of 1 (endo CH2, exo CH2 and CH).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route to complexes 1–6.

Figure 1.

Selected area of the 1H NMR spectra of free anastrozole (red), complex 1 (green) and complex 2 (blue) in CDCl3, showing the resonances corresponding to their triazole protons.

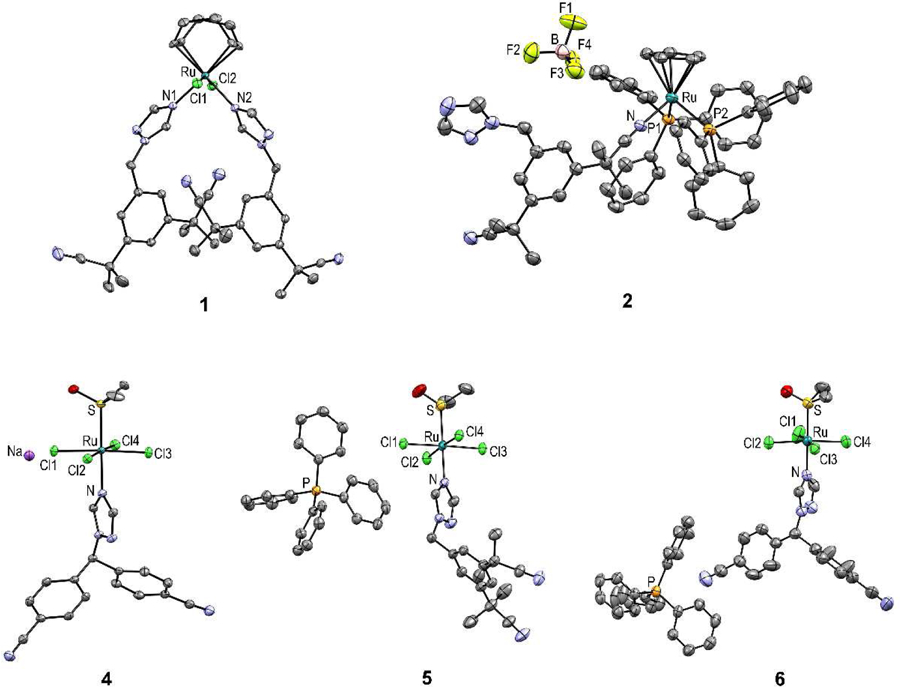

Figure 2.

ORTEP diagrams of 1, 2 and 4-6 with thermal ellipsoids drawn at the 50% probability level. Note that only one site is shown for the disordered dimethyl sulfoxide molecule in the asymmetric unit of 6, whereas two co-crystallized molecules of water in the asymmetric unit of 2 are omitted for clarity.

The solid-state structure of all compounds (except 3) was also confirmed by single crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 2 and Table S1). The six-coordinate metal center in 1 exhibits a distorted octahedral geometry. The Ru-C bond lengths are similar to those reported for other Ru(II)COD complexes [33, 58, 59]. The two chloride ligands trans to one another are directed away from the 1,5-COD ligand (the Cl1–Ru1–Cl2 bond angle is 159.95(2)°), a common distortion found for ligands axial to an equatorial plane containing 1,5-COD in ruthenium(II) complexes [33, 58, 59]. The two anastrozole ligands are cis to one another (N1-Ru1-N2 89.87(6)°) and trans to 1,5-COD. Compound 2 adopts a piano stool geometry, which is typical of cationic half-sandwich ruthenium complexes [34, 39]. As previously stated, X-ray analysis data obtained for this complex confirmed the coordination of the anastrozole through one of its nitrile moieties. This is the first example of this coordination mode for a ruthenium complex bearing anastrozole. The Ru-N bond length in 2, 2.048(3) Å, is in the same range as bond lengths reported for other nitrile-coordinated Ru(II)Cp complexes (2.056(3) Å [60] and 2.053(2) Å [61]) and Ru(II)-arene complexes (2.066(4) Å [62] and 2.050(4) Å [63]), but as expected, significantly shorter than the ones noted for 1 (Ru-N1:2.136(1) Å and Ru-N2: 2.133(1) Å) and for previously reported Ru(II)-arene complexes of triazole-coordinating anastrozole [26]. The crystallography data for 4-6 also revealed a disordered octahedral geometry, which is well documented and characteristic for this type of Ru(III) complexes [64–67]. All the synthesized Ru(III) species include four chloride ligands in the equatorial positions and a DMSO molecule bound via its sulfur atom trans to the triazol e ring of anastr ozole or letrozole in the axial position. The Ru-N bond lengths observed in the structure of all Ru(III) species are very similar to one another (Ru-N: 4, 2.091(2); 5, 2.103(2); 6, 2.093(3)) and to those reported for structurally similar complexes [67, 68]. The bond lengths and angles are also similar to those found in other NAMI-A derivatives [65–68].

DMSO was selected to prepare stock solutions of the compounds to assess their biological activity. DMSO is commonly used as a solvent of choice for this purpose as it allows the biological evaluation of compounds with poor aqueous solubility and does not induce noticeable in vitro or in vivo cytotoxicity at low concentrations. Prior to performing biological experiments, the solubility of the complexes in DMSO was estimated by measuring the UV-Vis absorbance of solutions of various concentrations after fine filtration. All complexes were found to be soluble in DMSO at concentrations as high as 20 mM, except complex 6 for which the biologically activity was not assessed. The stability of the complexes in DMSO (2 mM, 15 min) was also evaluated by NMR spectroscopy (only for the diamagnetic species). Whereas the 1H NMR spectrum of complex 2 revealed its high stability in DMSO (only 2% of free anastrozole was observed) (Figure S1), the 1H NMR spectrum of compound 1 revealed a much lower stability in this solvent. Although the 1H NMR spectrum of 1 (Figure S1) indicated that 1 remained the major species in solution, the appearance of two new series of peaks corresponding to free anastrozole (25%) and a new complex bearing anastrozole discouraged us from pursuing the biological activity assessment of compound 1. The stability of 2 in DMSO was further confirmed by UV-Vis spectrometry experiments. No apparent change was observed in the absorption spectrum of this compound over 1 h (Figure S2).

To further investigate the stability of 2-5 under conditions similar to those of the tritiated water-release assay of aromatase activity, a previously established HPLC technique [26] was used, allowing the measurement of the amount of released anastrozole or letrozole after a 1.5 h incubation of the complexes in full DMEM/F12 medium (with a maximum 0.1% DMSO) at 10 μM. Whereas all three Ru(III) complexes underwent transformation(s) in media, resulting in a significant release of their ligands (Table S2), compound 2 was found to be highly stable under the conditions tested (only 4% of released anastrozole was detected). Since complex 2 was the only species found to be stable under biologically relevant conditions, its solubility was verified by UV-Vis spectrometry under conditions similar to those used for the in vitro and in vivo experiments: i) in full DMEM/F12 medium (0.1% DMSO) and ii) in water (max 0.5% DMSO), respectively (Figure S3). Compound 2 was found to be highly soluble at all tested concentrations (up to 15 μM in water and up to 20 μM in culture medium), confirming the suitability of this compound for biological experiments.

The cytotoxicity of complex 2 was evaluated at different concentrations using a sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay [69] in different human cell lines: MCF7 and T47D (ER+ breast cancer), MDA-MB-231 (ER− breast cancer), H295R (adrenocortical carcinoma which expresses high levels of the aromatase enzyme) and MCF12A (non-cancerous breast) [70, 71]. IC50 values were determined after a 48 h exposure of the cancer cells to the complex (Table 1).

Table 1.

IC50 values determined for 2 and cisplatin in human cancer MCF7, T47D, H295R, MDA-MB-231 and non-cancerous MCF12A cell lines and corresponding selectivity index.

| IC50 (μM)a | Selectivity index (SI)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | cisplatin | 2 | cisplatin | |

| MCF7 | 0.50 (±0.09) | 20.1 (±3.5) | 1.16 | 2.12 |

| T47D | 0.32 (±0.03) | >150 | 1.81 | <0.28 |

| MDA-MB-231 | 0.39 (±0.09) | 32.4 (±7.4) | 1.49 | 1.32 |

| H295R | 0.63 (±0.05) | 86.5 (±1.2) | 0.92 | 0.49 |

| MCF12A | 0.58 (±0.02) | 42.7 (±7.2) | - | - |

Inhibitory activity was determined by exposure of cell lines to each complex for 48h and expressed as the concentration required to inhibit cell metabolic activity by 50% (IC50). Errors correspond to the standard deviation of two to four independent experiments.

SI= IC50 (non-cancerous MCF12A cell line) / IC50 (cancer cell line)

In contrast to anastrozole alone (IC50 > 100 μM in all cell lines, results not shown), compound 2 displayed a high cytotoxicity against all the cancer cell lines with IC50 values lower than 1 μM. Although complex 2 approximately equally affected the healthy cell line tested with a selectivity index of 1.16, it is important to keep in mind that i) the same in vitro lack of selectivity was also observed for the widely used chemotherapeutic drug cisplatin (SI<<1 in case of T47D and H295R cells) and that ii) although considered as an acceptable indicator, the cytotoxicity of a compound in vitro does not necessarily reflect their acute systemic toxicities and as a consequence, in vivo toxicities cannot be predicted from in vitro experiments with high confidence [72–74]. Importantly, complex 2 was more cytotoxic than cisplatin in all (cancer) cell lines used in this study, particularly in H295R and T47D cells. Notably, compound 2 was not only found to be highly cytotoxic in ER+ breast cancer cells (IC50 = 0.50 ± 0.09 μM, MCF7; 0.32 ± 0.03 μM, T47D) but also in a triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell line (IC50 = 0.39 ± 0.09 μM, MDA-MB-231), suggesting a mode of action that is independent of the estrogen receptor status of the cells. Indeed, it is of high importance to identify drug candidates for the treatment of aggressive hormone receptor negative (HR-, TNBC) breast cancers (about 10–20% of cases) for which endocrine therapies that target the hormone receptors are ineffective [48, 75]. The IC50 values observed for compound 2 are in the range expected for Ru(II)Cp complexes in both ER+ breast cancer and TNBC cell lines (0.03–20 μM) [46, 47, 76–78], confirming the high potential of this class of ruthenium complexes for breast cancer treatment. Finally, compound 2 is a rare example of a ruthenium complex with significant cytotoxicity in H295R cells (IC50 = 0.63 ± 0.05 μM), warranting further investigations on the design of ruthenium species for the treatment of aggressive adrenocortical carcinomas. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that in vitro cytotoxicity is not necessarily representative of in vivo antitumor activity, due to the potential impact of the tumor microenvironment on the tumor growth and drug effectiveness [79, 80].

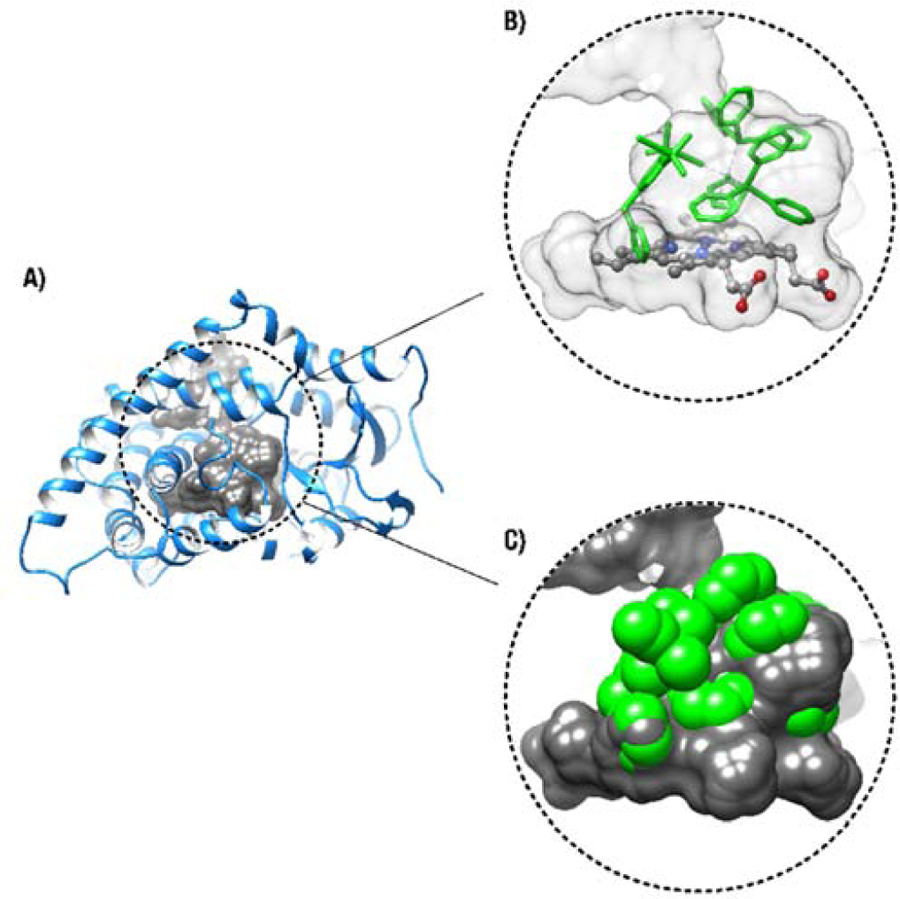

Binding of third generation aromatase inhibitors to the catalytic centre of the cytochrome P450 enzyme aromatase (CYP191A1) (consisting of an iron porphyrin complex) via their triazole nitrogen atom is considered to be their main mode of action [81]. Therefore, considering the availability of the triazole ring in the structure of 2, we performed a molecular modeling study to evaluate the potential occurrence of interactions between this ruthenium complex and the enzyme using a docking simulation model we previously developed [26], based on the crystal structure of human placental aromatase cytochrome P450 (CYP19A1) (Figure 3). These types of interactions between transition metal complexes and proteins (or DNA) were previously studied by other groups [82–84]. Molecular docking results suggest that bonding between the heme iron of CYP19 and triazole nitrogen atom is unlikely to occur. These results also reveal that significant conformational re-arrangements of the protein would be required to accommodate compound 2 inside the active-site cavity of aromatase. Our simulations show that the interaction between 2 and the enzyme is energetically unfavorable because of significant steric clashes between compound 2 atoms and amino acids within the active-site cavity (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Molecular docking of compound 2 inside the active-site cavity of aromatase. A) The active-site cavity of aromatase is shown in gray and the protein model is displayed as a blue ribbon. The illustrated surface represents the solvent-accessible area of the active site. B) Preferred conformer extracted for the ternary complex between the enzyme, cofactor group (heme), and compound 2. The cofactor and compound 2 are respectively depicted as ball-and-stick and green stick models. C) Disruption of the internal cavity of the enzyme by compound 2, illustrated as full atomic volume representation of van der Waals radii. Compound 2 atoms are shown as green spheres calculated according to the Corey-Pauling-Koltun model for van der Waals radii. Compound 2 atoms directly clash with amino acids within the active site of the enzyme, suggesting that such ternary complex formation is energetically unfavorable and nonspontaneous.

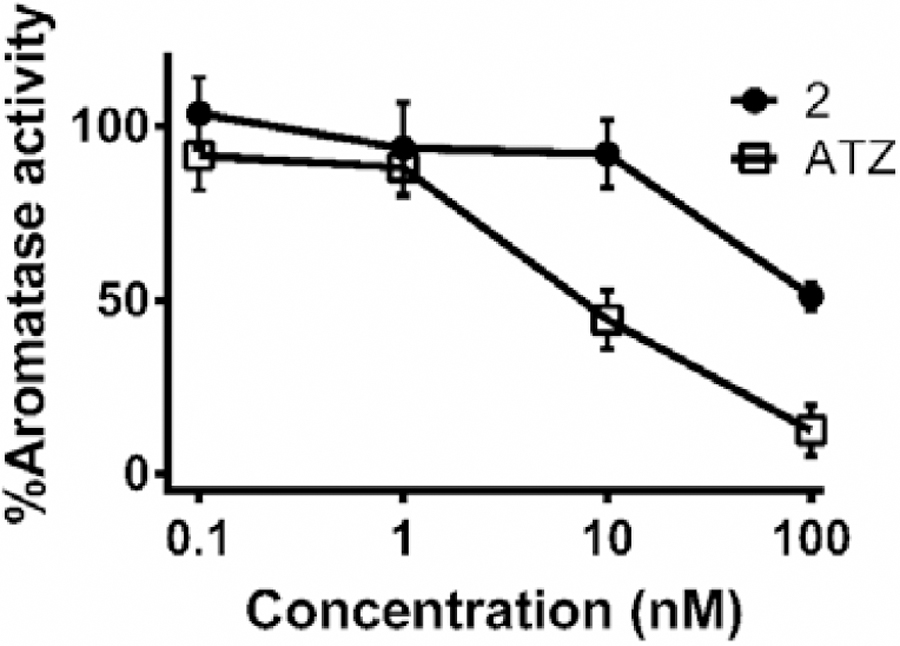

In the absence of conformational rearrangements of aromatase, the bulkiness of 2 (bearing two bulky triphenylphosphine ligands) would prevent this complex from passing through the solvent-accessible access channel, preventing it to reach the active site of aromatase. This was further supported by results obtained from a tritiated water-release experiment we performed to assess the in vitro aromatase inhibitory effect of 2. This method was previously reported as a sensitive and reproducible technique for aromatase activity assessment [85, 86]. The H295R cell line was selected for this study as it expresses high levels of the aromatase enzyme [70, 87]. As we previously reported for the investigation of the aromatase activity of H295R cells exposed to ruthenium species [26], H295R cells were co-incubated with 1β−3H-androstenedione and compound 2 (or anastrozole) for 1.5 h. The radioactivity of the tritium oxide produced from the conversion of the labeled androgen to its corresponding estrogen, catalyzed by the aromatase enzyme, was quantified and reported as an indication of aromatase activity (Figure 4). Because of the high cytotoxicity of 2 in H295R cells (IC50 = 0.63 ±0.05 μM), potential aromatase inhibition by compound was assessed at concentrations no greater than 100 nM (compound 2 becomes slightly cytotoxic at 1μM when incubated for 1.5h). As predicted from the docking simulation, a significantly less aromatase inhibition was observed in cells exposed to 2 compared to those treated with free anastrozole. No significant inhibition of aromatase activity was observed by complex 2 up to 10 nM, whereas about 50% inhibition of enzyme activity was observed by anastrozole alone at 10 nM (Figure 4). It is likely that the slight aromatase inhibitory activity observed for 2 at higher concentrations was a consequence of free anastrozole released from the complex (4%, Table S2) under the conditions of the assay, making it difficult to draw a definite conclusion about the aromatase inhibitory activity of the complex itself.

Figure 4.

Effects of the exposure of H295R cells to anastrozole (ATZ) and 2 on the aromatase activity. Cells were treated for 1.5 h with the indicated concentrations of the compounds. Values represent the mean ± SD.

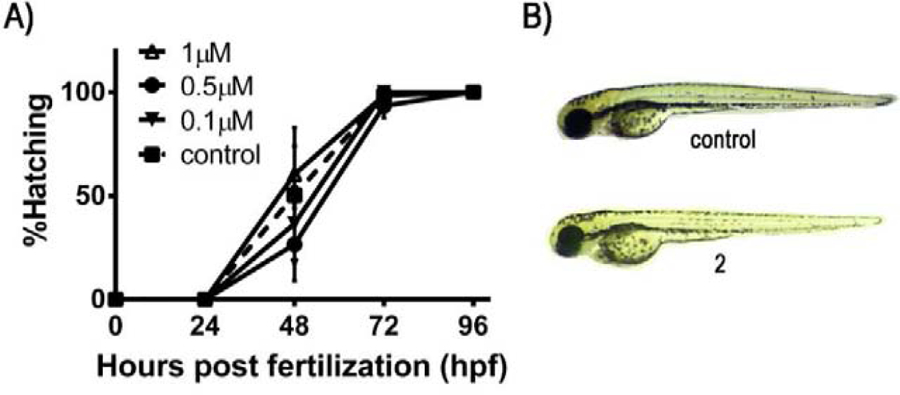

The in vivo toxicity of 2 was determined in a zebrafish embryo model. Several publications support the use of this assay as a suitable model for the investigation of the in vivo toxicity of ruthenium species [26, 27, 88]. The zebrafish has become a prominent in vivo model in toxicology and drug discovery due to several advantages such as high fecundity (200–300 embryos per mating pair per week), ease of manipulation, embryo transparency, high degree of genetic conservation with humans and low cost [88–90]. Importantly, results arising from zebrafish toxicity screenings have been used as prediction tools prior to undertaking preclinical and clinical studies [91]. Accordingly, mortality rates, hatching rates and phenotype changes of zebrafish embryos exposed to 2 at concentrations (0.1μM, 0.5μM and 1μM) around its IC50 value for cytotoxicity in human cancer cells were determined at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post-fertilization (hpf) (Figure 5). Compared to untreated control embryos, no apparent mortality (data not shown), hatching delay or phenotype changes were observed in zebrafish embryos treated with 2 at the tested concentrations. It is noteworthy that we have previously reported significant inhibition of hatching rate for zebrafish embryos exposed to cisplatin at concentrations far less than its IC50 value in human cancer cells [26, 27]. There are also a few studies reported for which Ru(II)Cp complexes have been investigated for their overall toxicity in a zebrafish model [78, 92, 93]. Although different conditions have been used for these studies making us unable to draw a certain conclusion, signs of toxicity such as delayed hatching, mortality and abnormalities such as pericardial edema, yolk sac edema, curved tail and head malfunction have been observed for some of the reported Ru(II)Cp complexes at the tested concentrations. Thus, compound 2 could be considered a promising candidate for further in vivo investigations.

Figure 5.

(A) Effect of 2 on the hatching rate of developing zebrafish embryos. Hatching rates were assessed at 0.1, 0.5 and 1 μM over 4 days post-fertilization (96 hpf). Control hatching rates are shown as a dashed line. (B) Gross morphological phenotypes of zebrafish embryos: untreated (control) and treated with 12.5 μM of 2. Results are expressed as means ± standard deviation of three independent experiments (a total of 60 embryos).

Conclusion

From this study of a series of ruthenium complexes bearing anastrozole or letrozole (1–6), we observed that the solubility and the stability of the complexes can be highly affected by their type of backbone, the nature of their ligands or counterions and the type of coordinating site of the ligand. Our study clearly shows that Ru(II)Cp complex 2, the only species in this series for which anastrozole is coordinated ruthenium through the nitrile moiety (and not via the nitrogen of the triazole ring), was the only complex found to be stable in DMSO and in cell culture medium. Whereas Ru(II)Cp complexes have been overlooked for their anticancer properties, in vitro and in vivo investigations of 2 demonstrate a high potential for this type of complexes in cancer treatment. Furthermore, results from the aromatase inhibition assay and the molecular docking simulation suggest that the bulkiness of a ruthenium complex can be a factor preventing its interaction with the targeted enzyme, and that bulky moieties such as PPh3 may not be ligands of choice for that purpose. Moreover, this study opens the door to the development of a novel class of Ru(II)Cp complexes for breasts cancer therapy, particularly against TNBCs which respond poorly to existing chemotherapeutic agents.

Experimental section

General comments.

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. Experiments were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques, and solvents were dried using a solvent purification system (Pure Process Technology). Anastrozole and letrozole were purchased from Triplebond and AK scientific, respectively. RuCl3.xH2O, 5-cyclooctadiene, dicyclopentadiene, triphenylphosphine, and silver tetrafluoroborate were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. [Ru(COD)Cl2]n [94], RuCp(PPh3)2Cl [95], and Na[trans-RuCl4(DMSO)2] [96] were prepared according to previously reported procedures. Tecan Infinite M1000 PRO microplate reader was used to read the absorbance of multiwell plates (at 510 nm) for SRB assay. NMR spectra (1H, 13C{1H}, COSY, HSQC, and ROESY) were recorded on a 400 MHz Varian or 600 MHz Bruker Avance III NMR spectrometers. Chemical shifts (δ) and coupling constants are expressed in ppm and Hz, respectively. 1H and 13C{1H} spectra were referenced to solvent resonances, and spectral assignments were confirmed by 2D experiments. The purity of all ruthenium complexes (>95%) was assessed by elemental analyses (Laboratoire d’Analyze Élémentaire, Department of Chemistry, Université de Montréal). High-resolution and high accuracy mass spectra (HR-ESI-MS) were obtained using an Exactive Orbitrap spectrometer from ThermoFisher Scientific (Department of Chemistry, McGill University). Diffraction measurements were performed on a SMART APEX II diffractometer equipped with a CCD detector, an Incoatec IMuS source (Cu) and a Quazar MX mirror (1 and 2) or a Bruker Venture diffractometer (a liquid Ga Metal Jet source) equipped with a Photon 100 CMOS detector, a Helios MX optics and a Kappa goniometer (4–6) (Department of Chemistry, Université de Montréal). All statistical analyses were done using the GraphPad Prism 6.01 software. ANOVA analysis was used for testing the significance of the difference between the means and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Complex synthesis and characterization

RuCOD(ATZ)2Cl2 (1).

Acetonitrile (18 mL) was added to anastrozole (0.208 g, 0.71 mmol), and [Ru(COD)Cl2]n (0.100 g, 0.35 mmol). The mixture was heated under reflux for 48h and then cooled to room temperature and filtered. The filtrate was evaporated to dryness and the crude yellow compound was purified by flash chromatography (silica gel) with ethyl acetate:hexane (4:1) as the mobile phase. Compound 1 (0.020 g, 13%) was obtained as a light-yellow precipitate.

Microwave-assisted synthesis.

A mixture of [Ru(COD)Cl2]n (0.05 g, 0.18 mmol) and anastrozole (0.104 g, 0.36 mmol) in acetonitrile (10 mL) was heated in a microwave reactor at 80 °C for 25 min (set points: pressure 15 psi, power 200 W). The solvent was removed under vacuum and a light-yellow color product (0.034 g, 22%) was obtained after purification by column chromatography as mentioned above.1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 1.71 (s, CH3, 24H), 2.06 (m, C8H12, 4H), 2.66 (br, C8H12, 4H), 4.09 (br, C8H12, 4H), 5.34 (s, CH2, 4H), 7.26 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, ArH, 4H), 7.49 (t, J = 1.7 Hz, ArH, 2H), 8.53 (s, Htriazole, 2H), 8.93 (s, Htriazole, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ 29.04 (s), 30.05 (s), 37.30 (s), 53.82 (s), 89.53 (s), 122.02 (s), 123.76 (s), 124.25 (s), 135.87 (s), 143.4 (s), 145.15 (s), 151.92 (s). Found (%): C, 57.94; H, 5.83; N, 15.92. C42H50Cl2N10Ru1 requires C, 58.17; H, 5.82; N, 16.16. HR-ESI-MS m/z (+): found 889.25 [M + Na]+ (calc. 889.25).

RuCp(PPh3)2(ATZ)BF4 (2).

To a suspension of RuCp(PPh3)2Cl (0.200 g, 0.276 mmol) in acetone (20 mL) were added anastrozole (0.164 g, 0.558 mmol) and AgBF4 (0.060 g, 0.308 mmol). The solution was refluxed for 2h until the colour changed from orange to pale yellow. The solution was centrifuged and the supernatant was evaporated under vacuum. The residue was dissolved in 2 mL of dichloromethane and was passed through a celite pad. Diethyl ether was added to the filtrate and the resulting precipitate was washed with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL) and diethyl ether (3 × 10 mL). Compound 2 (0.107 g, 36%) was obtained as a pale-yellow precipitate. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ 1.42 (s, CH3, 6H), 1.70 (s, CH3, 6H), 4.51 (s, C5H5, 5H), 5.51 (s, CH2, 2H), 7.00 (m, HPPh3, 12H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.16 Hz, HPPh3, 12H), 7.33 (t, J = 7.17 Hz, HPPh3, 6H), 7.39 (t, J = 1.76, ArH, 1H), 7.47 (s, ArH, 1H), 7.73 (s, ArH, 1H), 7.97 (s, Htriazole, 1H), 8.60 (s, Htriazole, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ 27.65 (s), 29.13 (s), 37.50 (s), 39.39 (s), 52.47 (s), 83.80 (s), 121.66 (s), 124.34 (s), 124.91 (s), 126.26 (s), 128.39 (t), 130.13 (s), 133.06 (t), 135.75 (t), 136.21 (s), 138.28 (s), 141.38(s), 142,95(s), 144.38 (s), 152.10 (s). 31P{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 200 MHz): δ 41.50. Found (%): C, 62.40; H, 5.23; N, 6.21. C58H54BF4N5P2Ru·5/2H2O requires C, 62.42, H 5.33, N 6.28. HR-ESI-MS m/z (+): found 984.29 M+ (calc. 984.29), 691.13 [M+-ATZ]+ (calc. 691.13).

Na[trans-RuCl4L(DMSO)] (L = ATZ, 3; L = LTZ, 4).

Na[trans-RuCl4(DMSO)2] (0.36 mmol, 0,150 g) and L (1.08 mmol, L= ATZ: 0.315 g; L=LTZ: 0.303 g) were dissolved in acetone (10 mL) and the reaction was carried out overnight. The solution was evaporated to dryness and the crude compound was purified by flash chromatography (silica gel) with dichloromethane:methanol (20:1) as the mobile phase. 3 and 4 were obtained as light-yellow precipitates (3: 0.128 g, 56%; 4: 0.149 g, 66%). 3: Found (%): C, 35.02; H, 4.22; N, 10.65; S, 5.38. C19H25Cl4N5NaORuS·½H2O requires C, 35.29; H, 4.06; N, 10.84; S, 4.95. HR-ESI-MS m/z (−): found 614.96 M- (calc. 614.96); 4: Found (%): C, 35.50; H, 3.15; N, 10.55, S, 4.85. C19H17Cl4N5NaORuS.H2O requires C, 35.25; H, 2.96; N, 10.82; S, 4.95. HR-ESI-MS m/z (−): found 606.89 M- (calc. 606.89).

PPh4[trans-RuCl4L(DMSO)] (L = ATZ, 5; L = LTZ, 6).

PPh4Cl (1.25 mmol, 470 mg) was added to a solution of 3 (0.125 mmol, 80 mg) or 4 (0.125 mmol, 79 mg) in methanol (8 mL) and the reaction was stirred at ambient temperature for 4 h. The solution was filtered, and the filtrate was dried under vacuum. The residue was washed by distilled water (4 × 20mL) and diethyl ether (2 × 10 mL). Compounds 5 and 6 were obtained as yellow powders (5: 0.083 g, 69.6%; 6: 0.045 g, 38.6%). 5: Found (%): C, 53.66; H, 4.83; N, 7.24; S, 3.96. C43H45Cl4N5OPRuS·½ H2O requires C, 53.63; H, 4.82; N, 7.28; S, 3.32. HR-ESI-MS m/z (−): found 614.96 M- (calc. 614.96), m/z (+): found 339.13 X+ (calc. 339.13); 6: Found (%): C, 54.24; H, 3.97; N, 7.35, S, 3.36. C43H37Cl4N5OPRuS·H2O requires C, 54.60; H, 3.95; N, 7.41; S, 3.38. HR-ESI-MS m/z (−): found 606.89 M- (calc. 606.89), m/z (+): found 339.13 X+ (calc. 339.13).

Solubility in DMSO, media/DMSO, water/DMSO.

UV-vis spectroscopy was used to evaluate the solubility of 1-6 in DMSO. Accordingly, solutions of 1-6 at different concentrations (5, 10, 15, 20 mM) were prepared in DMSO. The solutions were filtered using a short celite pad and were then diluted 10 times in DMSO prior to UV-Vis measurements. The solubility of 2 was also investigated in phenol red free DMEM-F12 (DMSO 0.1%) at 0.01, 0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20 μM and in water (max DMSO 0.5%) at 1, 5, 10, 15 μM. All solutions were filtered (using a 0.2 μm syringe filter) prior to the UV-Vis measurements and the absorbance (350 nm-370 nm) was recorded using a microplate reader. The linearity between concentration and absorbance was considered as an indication of the solubility of the compounds at the desired concentrations. It is important to note that no supplementary technique was used here to evaluate if nanoaggregates were formed under these conditions.

Stability in cell culture media/DMSO.

A previously developed HPLC-UV method [26] was used to measure the anastrozole (or letrozole) release in cell culture media supplemented with 0.1% DMSO. Stock solutions (104 μM) of 2-5 were prepared in DMSO. 10 μM solutions of the compounds were prepared by adding 20 μL of a stock solution to 20 mL of DMEM/F12. Solutions were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h, and further steps were achieved as described previously [26]. Briefly, after incubation, anastrozole or letrozole was retrieved from the media solution by liquid/liquid extraction using diethyl ether. After evaporation of the diethyl ether and after dissolving the residue in 2 mL of acetone, the solution was passed through a thin layer of silica (using 20 mL of acetone) to completely recover anastrozole (or letrozole) while minimizing the amount of undesired media residue in the final HPLC samples. Acetone was evaporated to dryness and the residue was dissolved in 1 mL of HPLC grade acetone containing 100 μM hydrocortisone as an external standard. The HPLC sample was injected into an Agilent UHPLC system (1260 Infinity GPC/SEC) using an Agilent Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm, 2.7 μm) through a 13 min gradient of a mixture of acetonitrile and water at a flow rate of 2 mL/min: (a) 0–1 min, water, 100%; (b) 1–4 min, acetonitrile, 0–30%; (c) 4–10 min, acetonitrile, 30%; (d) 10–11 min, acetonitrile, 30%−100%; 11–13 min, acetonitrile, 100%. UV absorbance was acquired at 215 and standard curves of anastrozole and letrozole as the ones reported before [26] were used to quantify the amount of the aromatase inhibitors. All the experiments were carried out in three replicates.

X-ray diffraction analysis.

Single crystals suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained by the room temperature slow evaporation of solutions of 1 (in ethyl acetate), 4 (in methanol), 5 (in dichloromethane), and 6 (in dichloromethane/diethyl ether). Single crystals of 2 were obtained from an ethyl acetate solution kept at at 4°C for two weeks. Cell refinement and data reduction were done using APEX2. Absorption corrections were applied using SADABS. Structures were solved by direct methods using SHELXS-97 and refined on F2 by full-matrix least squares using SHELXL-97 or SHELXL-2014. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, whereas hydrogen atoms were refined isotropic on calculated positions using a riding model [97–99].

Cell culture.

All the protocols reported for biological studies were approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of INRS – Centre Armand-Frappier Santé Biotechnologie. All cell culture products were obtained from commercial sources such as Gibco, Sigma Aldrich, Corning, and Invitrogen. RPMI 1640 supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%) was used to culture human breast cancer MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Human breast cancer T47D cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with HEPES (2.38 g/L), sodium pyruvate (0.11 g/L), glucose (2.5 g/L), insulin bovine (10 μg/mL), and fetal bovine serum (10%). Adrenocortical carcinoma H295R cells were grown in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with Nu Serum (2.5%) and ITS (1%). MCF12A cells were maintained in phenol Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium Ham’s F12 (DMEM/F12) culture medium supplemented with 5% (v/v) horse serum, hEGF recombinant (20 ng/mL), hydrocortisone (500 ng/mL), and insulin (10 μg/mL). All growth media were supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were propagated according to ATCC guidelines.

Sulforhodamine B (SRB) Assay.

The cytotoxicity of 2, anastrozole and cisplatin in MCF7, T47D, MDA-MB-231 and MCF12A cells were evaluated using the SRB assay. Cells were cultured in 96-well plates (104 cells/well) and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 ° C overnight. Cells were treated with different concentrations of each compound, carrier (media containing maximum 0.5% DMSO) and positive control (media containing 25% DMSO). The plates were incubated for 48 h and further steps were done as previously reported [26]. IC50 values were determined by the plots of viability versus concentration. Error bars were calculated as the standard error of three independent experiments.

Aromatase activity measurement.

Aromatase activity was measured using a tritiated water-release assay. H295R cells that can express high level of aromatase enzyme in vitro [70] were cultured in 24-well plates (100,000 cells/well) containing 1 mL of DMEM/F-12 supplemented with Nu Serum and ITS and were incubated for 24h. After removing the medium and washing cells with 500 μL PBS, a volume of 250 μL of phenol red free DMEM/F-12 containing 54nM 1β−3H-androstenedione and different concentrations of anastrozole and 2 (0.1, 1, 10 and 100 nM) were added to each well, and cells were incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C (5% CO2). Further steps were performed as described previously [71]. Tritiated water in a liquid scintillation cocktail was counted using a Microbeta Trilux (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Massachusetts). Incubations in the absence of cells (blanks) and in the presence of DMSO 0.1% (which was the concentration used to dissolve the complexes in the growth media for this study) were included as controls.

Zebrafish embryo assay.

Wild-type zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos were raised at 28.5 °C and staged as previously described [100]. Embryos at the 2-cell or 4-cell stage were seeded in 6-well plates and exposed to 5 mL fish medium containing 2 at different concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1 μM). Final concentration of DMSO in which the stock solutions were prepared was 0.5%. The mortality, gross morphology, and hatching rates of the zebrafish embryos without and with the desired compounds were observed every 24h for a period of 96h under a stereo microscope (Leika S6E). The medium (containing the compound to be tested) was refreshed after 48 h for each experiment. A no-treatment control was also included. Experiments were performed in triplicates, and a total of 60 embryos from the pooling of three different crosses have been used per each treatment. Zebrafish experiments were performed following a protocol approved by the Canadian Council for Animal Care (CCAC) and our local animal care committee.

Virtual docking of compound 2 to human aromatase.

Human aromatase (PDB entry 5JL6) was previously solvated with water molecules using the YASARA minimization system and standard protocols [101] Complex 2 was used as ligand and its structure was generated with the XT structure solution program and refined using a least squares minimization protocol [26]. Compound 2 was then used in combination with the heme group as cofactor and the energetically minimized aromatase structure, as previously described [26]. We used the cavity detection standard protocol incorporated in the Molegro Virtual Docker 6.0 suite as first step to identify and establish the active-site cavity of the enzyme. The best ternary complex solution for this compound was obtained after a 20-run simulation of 3,500 iteration cycles with an initial population of 100 conformers per iteration. The preferred conformer arose from a protocol that explored up to 7,000,000 combinations. The MolDock scoring function was used to score the best conformer solutions without the incorporation of solvent molecules [102]. USCF Chimera 1.1 was used for molecular structure visualization [45].

Supplementary Material

The synthesis and characterization of Ru(II) and Ru(III) complexes bearing a third-generation aromatase inhibitor are reported

The Ru(II)Cp 2 complex is stable under biologically relevant conditions

Complex 2 shows high in vitro cytotoxicity (IC50 values < 1 μM) in human breast cancer cell lines (ER+ and TNBC) and a human adenocarcinoma cell line

Complex 2 displays a lower toxicity in zebrafish embryos than cis-platin at concentrations surrounding their IC50 values

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (A.C., J.T.S. and N.D.), the Fonds de Recherche du Québec Santé (FRQS) (A.C., S.A.P., N.D.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (S.A.P.), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) (A.C., S.A.P., and N.D.), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (N.D.) and the Armand-Frappier Foundation (scholarship to G.G.). We would like to thank Prof. David Chatenet and Prof. Isabelle Plante for providing the human cancer cell lines used in this study, as well as Prof. Charles Ramassamy for providing access to his laboratory instrumentation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession Codes

CCDC 1962264-1962268 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Allardyce CS, Dyson PJ, Metal-based drugs that break the rules, Dalton Trans 45 (2016) 3201–3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Berndsen RH, Weiss A, Abdul UK, Wong TJ, Meraldi P, Griffioen AW, Dyson PJ, Nowak-Sliwinska P, Combination of ruthenium(II)-arene complex [Ru(η6-p-cymene)Cl2(pta)] (RAPTA-C) and the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor erlotinib results in efficient angiostatic and antitumor activity, Sci. Rep 7 (2017) 43005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Johnstone TC, Park GY, Lippard SJ, Understanding and improving platinum anticancer drugs--phenanthriplatin, Anticancer Res 34 (2014) 471–476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Li J, Guo L, Tian Z, Zhang S, Xu Z, Han Y, Li R, Li Y, Liu Z, Half-Sandwich Iridium and Ruthenium Complexes: Effective Tracking in Cells and Anticancer Studies, Inorg. Chem 57 (2018) 13552–13563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Williams DS, Atilla GE, Bregman H, Arzoumanian A, Klein PS, Meggers E, Switching on a Signaling Pathway with an Organoruthenium Complex, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 44 (2005) 1984–1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Smalley KSM, Contractor R, Haass NK, Kulp AN, Atilla-Gokcumen GE, Williams DS, Bregman H, Flaherty KT, Soengas MS, Meggers E, Herlyn M, An Organometallic Protein Kinase Inhibitor Pharmacologically Activates p53 and Induces Apoptosis in Human Melanoma Cells, Cancer Res 67 (2007) 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Alessio E, Thirty Years of the Drug Candidate NAMI-A and the Myths in the Field of Ruthenium Anticancer Compounds: A Personal Perspective, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2017 (2017) 1549–1560. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Leijen S, Burgers SA, Baas P, Pluim D, Tibben M, van Werkhoven E, Alessio E, Sava G, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM, Phase I/II study with ruthenium compound NAMI-A and gemcitabine in patients with non-small cell lung cancer after first line therapy, Invest. New Drug 33 (2015) 201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Holder AA, Lilge L, Browne WR, Lawrence MAW, Bullock JL, Ruthenium Complexes: Photochemical and Biomedical Applications, first ed., Wiley-VCH, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Burris HA, Bakewell S, Bendell JC, Infante J, Jones SF, Spigel DR, Weiss GJ, Ramanathan RK, Ogden A, Von Hoff D, Safety and activity of IT-139, a ruthenium-based compound, in patients with advanced solid tumours: a first-in-human, open-label, dose-escalation phase I study with expansion cohort, ESMO Open 1 (2016) e000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Monro S, Colón KL, Yin H, Roque J, Konda P, Gujar S, Thummel RP, Lilge L, Cameron CG, McFarland SA, Transition Metal Complexes and Photodynamic Therapy from a Tumor-Centered Approach: Challenges, Opportunities, and Highlights from the Development of TLD1433, Chem. Rev 119 (2019) 797–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bergamo A, Gaiddon C, Schellens JHM, Beijnen JH, Sava G, Approaching tumour therapy beyond platinum drugs: Status of the art and perspectives of ruthenium drug candidates, J. Inorg. Biochem 106 (2012) 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Thota S, Rodrigues DA, Crans DC, Barreiro EJ, Ru(II) Compounds: Next-Generation Anticancer Metallotherapeutics?, J. Med. Chem 61 (2018) 5805–5821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bonnet S, Why develop photoactivated chemotherapy?, Dalton Trans 47 (2018) 10330–10343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wernitznig D, Kiakos K, Del Favero G, Harrer N, Machat H, Osswald A, Jakupec MA, Wernitznig A, Sommergruber W, Keppler BK, First-in-class ruthenium anticancer drug (KP1339/IT-139) induces an immunogenic cell death signature in colorectal spheroids in vitro, Metallomics 11 (2019) 1044–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Castonguay A, Doucet C, Juhas M, Maysinger D, New Ruthenium(II)–Letrozole Complexes as Anticancer Therapeutics, J. Med. Chem 55 (2012) 8799–8806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kilpin KJ, Dyson PJ, Enzyme inhibition by metal complexes: concepts, strategies and applications, Chem. Sci 4 (2013) 1410–1419. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mu C, Prosser KE, Harrypersad S, MacNeil GA, Panchmatia R, Thompson JR, Sinha S, Warren JJ, Walsby CJ, Activation by Oxidation: Ferrocene-Functionalized Ru(II)-Arene Complexes with Anticancer, Antibacterial, and Antioxidant Properties, Inorg. Chem 57 (2018) 15247–15261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ang WH, Parker LJ, De Luca A, Juillerat-Jeanneret L, Morton CJ, Lo Bello M, Parker MW, Dyson PJ, Rational Design of an Organometallic Glutathione Transferase Inhibitor, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 48 (2009) 3854–3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brueggemeier RW, Hackett JC, Diaz-Cruz ES, Aromatase Inhibitors in the Treatment of Breast Cancer, Endocr. Rev 26 (2005) 331–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Goss PE, Strasser K, Aromatase inhibitors in the treatment and prevention of breast cancer, J. Clin. Oncol 19 (2001) 881–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jeselsohn R, Bergholz JS, Pun M, Cornwell M, Liu W, Nardone A, Xiao T, Li W, Qiu X, Buchwalter G, Feiglin A, Abell-Hart K, Fei T, Rao P, Long H, Kwiatkowski N, Zhang T, Gray N, Melchers D, Houtman R, Liu XS, Cohen O, Wagle N, Winer EP, Zhao J, Brown M, Allele-Specific Chromatin Recruitment and Therapeutic Vulnerabilities of ESR1 Activating Mutations, Cancer Cell 33 (2018) 173–186.e175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Krop IE, Mayer IA, Ganju V, Dickler M, Johnston S, Morales S, Yardley DA, Melichar B, Forero-Torres A, Lee SC, de Boer R, Petrakova K, Vallentin S, Perez EA, Piccart M, Ellis M, Winer E, Gendreau S, Derynck M, Lackner M, Levy G, Qiu J, He J, Schmid P, Pictilisib for oestrogen receptor-positive, aromatase inhibitor-resistant, advanced or metastatic breast cancer (FERGI): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial, Lancet Oncol 17 (2016) 811–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].O’Neill M, Paulin FEM, Vendrell J, Ali CW, Thompson AM, The aromatase inhibitor letrozole enhances the effect of doxorubicin and docetaxel in an MCF7 cell line model, BioDiscovery 6 (2012) e8940. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Miranda AA, Limon J, Medina FL, Arce C, Zinser JW, Rocha EB, Villarreal-Garza CM, Combination treatment with aromatase inhibitor and capecitabine as first- or second-line treatment in metastatic breast cancer, J. Clin. Oncol 30 (2012) e11016. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Golbaghi G, Haghdoost MM, Yancu D, López de los Santos Y, Doucet N, Patten SA, Sanderson JT, Castonguay A, Organoruthenium(II) Complexes Bearing an Aromatase Inhibitor: Synthesis, Characterization, in Vitro Biological Activity and in Vivo Toxicity in Zebrafish Embryos, Organometallics 38 (2019) 702–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Haghdoost MM, Golbaghi G, Letourneau M, Patten SA, Castonguay A, Lipophilicity-antiproliferative activity relationship study leads to the preparation of a ruthenium(II) arene complex with considerable in vitro cytotoxicity against cancer cells and a lower in vivo toxicity in zebrafish embryos than clinically approved cis-platin, Eur. J. Med. Chem 132 (2017) 282–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Haghdoost MM, Guard J, Golbaghi G, Castonguay A, Anticancer Activity and Catalytic Potential of Ruthenium(II)–Arene Complexes with N,O-Donor Ligands, Inorg. Chem 57 (2018) 7558–7567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Coverdale JPC, Romero-Canelón I, Sanchez-Cano C, Clarkson GJ, Habtemariam A, Wills M, Sadler PJ, Asymmetric transfer hydrogenation by synthetic catalysts in cancer cells, Nat. Chem 10 (2018) 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Moreno V, Lorenzo J, Aviles FX, Garcia MH, Ribeiro JP, Morais TS, Florindo P, Robalo MP, Studies of the Antiproliferative Activity of Ruthenium (II) Cyclopentadienyl-Derived Complexes with Nitrogen Coordinated Ligands, Bioinorg. Chem. Appl 2010 (2010) 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Côrte-Real L, Mendes F, Coimbra J, Morais TS, Tomaz AI, Valente A, Garcia MH, Santos I, Bicho M, Marques F, Anticancer activity of structurally related ruthenium(II) cyclopentadienyl complexes, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 19 (2014) 853–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Loughrey BT, Healy PC, Parsons PG, Williams ML, Selective Cytotoxic Ru(II) Arene Cp* Complex Salts [R-PhRuCp*]+X− for X = BF4−, PF6−, and BPh4−, Inorg. Chem 47 (2008) 8589–8591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Thangavel S, Rajamanikandan R, Friedrich HB, Ilanchelian M, Omondi B, Binding interaction, conformational change, and molecular docking study of N-(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)aniline derivatives and carbazole Ru(II) complexes with human serum albumins, Polyhedron 107 (2016) 124–135. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Florindo PR, Pereira DM, Borralho PM, Rodrigues CMP, Piedade MFM, Fernandes AC, Cyclopentadienyl–Ruthenium(II) and Iron(II) Organometallic Compounds with Carbohydrate Derivative Ligands as Good Colorectal Anticancer Agents, J. Med. Chem 58 (2015) 4339–4347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Moreno V, Font-Bardia M, Calvet T, Lorenzo J, Avilés FX, Garcia MH, Morais TS, Valente A, Robalo MP, DNA interaction and cytotoxicity studies of new ruthenium(II) cyclopentadienyl derivative complexes containing heteroaromatic ligands, J. Inorg. Biochem 105 (2011) 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Côrte-Real L, Robalo MP, Marques F, Nogueira G, Avecilla F, Silva TJL, Santos FC, Tomaz AI, Garcia MH, Valente A, The key role of coligands in novel ruthenium(II)-cyclopentadienyl bipyridine derivatives: Ranging from non-cytotoxic to highly cytotoxic compounds, J. Inorg. Biochem 150 (2015) 148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Florindo P, Marques IJ, Nunes CD, Fernandes AC, Synthesis, characterization and cytotoxicity of cyclopentadienyl ruthenium(II) complexes containing carbohydrate-derived ligands, J. Organomet. Chem 760 (2014) 240–247. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Morais TS, Valente A, Tomaz AI, Marques F, Garcia MH, Tracking antitumor metallodrugs: promising agents with the Ru(II)- and Fe(II)-cyclopentadienyl scaffolds, Future Med. Chem 8 (2016) 527–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mavrynsky D, Rahkila J, Bandarra D, Martins S, Meireles M, Calhorda MJ, Kovács IJ, Zupkó I, Hänninen MM, Leino R, Cytotoxicities of Polysubstituted Chlorodicarbonyl(cyclopentadienyl) and (Indenyl)ruthenium Complexes, Organometallics 32 (2013) 3012–3017. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Côrte-Real L, Teixeira RG, Gírio P, Comsa E, Moreno A, Nasr R, Baubichon-Cortay H, Avecilla F, Marques F, Robalo MP, Mendes P, Ramalho JPP, Garcia MH, Falson P, Valente A, Methyl-cyclopentadienyl Ruthenium Compounds with 2,2′-Bipyridine Derivatives Display Strong Anticancer Activity and Multidrug Resistance Potential, Inorg. Chem 57 (2018) 4629–4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kasper C, Alborzinia H, Can S, Kitanovic I, Meyer A, Geldmacher Y, Oleszak M, Ott I, Wölfl S, Sheldrick WS, Synthesis and cellular impact of diene–ruthenium(II) complexes: A new class of organoruthenium anticancer agents, J. Inorg. Biochem 106 (2012) 126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nuno M, Francisco T, Andreia V, Fernanda M, António M, Tânia SM, Ana Isabel T, Fátima G, Garcia MH, In Vivo Performance of a Ruthenium-cyclopentadienyl Compound in an Orthotopic Triple Negative Breast Cancer Model, Anti Cancer Agent. Me 17 (2017) 126–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dutta B, Scolaro C, Scopelliti R, Dyson PJ, Severin K, Importance of the π-Ligand: Remarkable Effect of the Cyclopentadienyl Ring on the Cytotoxicity of Ruthenium PTA Compounds, Organometallics 27 (2008) 1355–1357. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Süss-Fink G, Arene ruthenium complexes as anticancer agents, Dalton Trans 39 (2010) 1673–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tomaz AI, Jakusch T, Morais TS, Marques F, de Almeida RFM, Mendes F, Enyedy ÉA, Santos I, Pessoa JC, Kiss T, Garcia MH, [RuII(η5-C5H5)(bipy)(PPh3)]+, a promising large spectrum antitumor agent: Cytotoxic activity and interaction with human serum albumin, J. Inorg. Biochem 117 (2012) 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Moreira T, Francisco R, Comsa E, Duban-Deweer S, Labas V, Teixeira-Gomes A-P, Combes-Soia L, Marques F, Matos A, Favrelle A, Rousseau C, Zinck P, Falson P, Garcia MH, Preto A, Valente A, Polymer “ruthenium-cyclopentadienyl” conjugates - New emerging anti-cancer drugs, Eur. J. Med. Chem 168 (2019) 373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Morais TS, Silva TJL, Marques F, Robalo MP, Avecilla F, Madeira PJA, Mendes PJG, Santos I, Garcia MH, Synthesis of organometallic ruthenium(II) complexes with strong activity against several human cancer cell lines, J. Inorg. Biochem 114 (2012) 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Al-Mahmood S, Sapiezynski J, Garbuzenko OB, Minko T, Metastatic and triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and treatment options, Drug Deliv. Transl. Re 8 (2018) 1483–1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, Sanders ME, Gianni L, Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease, Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 13 (2016) 674–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Trondl R, Heffeter P, Kowol CR, Jakupec MA, Berger W, Keppler BK, NKP-1339, the first ruthenium-based anticancer drug on the edge to clinical application, Chem. Sci 5 (2014) 2925–2932. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cao J, Wu Q, Zheng W, Li L, Mei W, Microwave-assisted synthesis of polypyridyl ruthenium(ii) complexes as potential tumor-targeting inhibitors against the migration and invasion of Hela cells through G2/M phase arrest, RSC Adv 7 (2017) 26625–26632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Beckford FA, Shaloski JM, Leblanc G, Thessing J, Lewis-Alleyne LC, Holder AA, Li L, Seeram NP, Microwave synthesis of mixed ligand diimine–thiosemicarbazone complexes of ruthenium(ii): biophysical reactivity and cytotoxicity, Dalton Trans (2009) 10757–10764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [53].Anderson TJ, Scott JR, Millett F, Durham B, Decarboxylation of 2,2’-Bipyridinyl-4,4’-dicarboxylic Acid Diethyl Ester during Microwave Synthesis of the Corresponding Trichelated Ruthenium Complex, Inorg. Chem 45 (2006) 3843–3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Haghdoost MM, Golbaghi G, Guard J, Sielanczyk S, Patten SA, Castonguay A, Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of cationic organoruthenium(ii) fluorene complexes: influence of the nature of the counteranion, Dalton Trans 48 (2019) 13396–13405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Geisler J, Differences between the non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors anastrozole and letrozole – of clinical importance?, Br. J. Cancer 104 (2011) 1059–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Geisler J, Haynes B, Anker G, Dowsett M, Lønning PE, Influence of Letrozole and Anastrozole on Total Body Aromatization and Plasma Estrogen Levels in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Patients Evaluated in a Randomized, Cross-Over Study, J. Clin. Oncol 20 (2002) 751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bharti N, Maurya MR, Naqvi F, Azam A, Synthesis and antiamoebic activity of new cyclooctadiene ruthenium(II) complexes with 2-acetylpyridine and benzimidazole derivatives, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 10 (2000) 2243–2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Widegren JA, Weiner H, Miller SM, Finke RG, Improved synthesis and crystal structure of tetrakis(acetonitrile)(η4–1,5-cyclooctadiene)ruthenium(II) bis[tetrafluoroborate(1−)], J. Organomet. Chem 610 (2000) 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Adams JJ, Del Negro AS, Arulsamy N, Sullivan BP, Unexpected Formation of Ruthenium(II) Hydrides from a Reactive Dianiline Precursor and 1,2-(Ph2P)2–1,2-closo-C2B10H10, Inorg. Chem 47 (2008) 1871–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Nyawade EA, Friedrich HB, Omondi B, Chenia HY, Singh M, Gorle S, Synthesis and characterization of new α,α′-diaminoalkane-bridged dicarbonyl(η5-cyclopentadienyl)ruthenium(II) complex salts: Antibacterial activity tests of η5-cyclopentadienyl dicarbonyl ruthenium(II) amine complexes, J. Organomet. Chem 799–800 (2015) 138–146. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Rüba E, Simanko W, Mauthner K, Soldouzi KM, Slugovc C, Mereiter K, Schmid R, Kirchner K, [RuCp(PR3)(CH3CN)2]PF6 (R = Ph, Me, Cy). Convenient Precursors for Mixed Ruthenium(II) and Ruthenium(IV) Half-Sandwich Complexes, Organometallics 18 (1999) 3843–3850. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Sortais J-B, Pannetier N, Holuigue A, Barloy L, Sirlin C, Pfeffer M, Kyritsakas N, Cyclometalation of Primary Benzyl Amines by Ruthenium(II), Rhodium(III), and Iridium(III) Complexes, Organometallics 26 (2007) 1856–1867. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Jung S, Ilg K, Brandt CD, Wolf J, Werner H, A series of ruthenium(ii) complexes containing the bulky, functionalized trialkylphosphines tBu2PCH2XC6H5 as ligands, J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans (2002) 318–327.

- [64].Alessio E, Balducci G, Lutman A, Mestroni G, Calligaris M, Attia WM, Synthesis and characterization of two new classes of ruthenium(III)-sulfoxide complexes with nitrogen donor ligands (L): Na[trans-RuCl4(R2SO)(L)] and mer, cis-RuCl3(R2SO)(R2SO)(L). The crystal structure of Na[trans-RuCl4(DMSO)(NH3)] · 2DMSO, Na[trans-RuCl4(DMSO)(Im)] · H2O, Me2CO (Im = imidazole) and mer, cis-RuCl3(DMSO)(DMSO)(NH3), Inorganica Chim. Acta 203 (1993) 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Velders AH, Bergamo A, Alessio E, Zangrando E, Haasnoot JG, Casarsa C, Cocchietto M, Zorzet S, Sava G, Synthesis and Chemical−Pharmacological Characterization of the Antimetastatic NAMI-A-Type Ru(III) Complexes (Hdmtp)[trans-RuCl4(dmso-S)(dmtp)], (Na)[trans-RuCl4(dmso-S)(dmtp)], and [mer-RuCl3(H2O)(dmso-S)(dmtp)] (dmtp = 5,7-Dimethyl[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine), J. Med. Chem 47 (2004) 1110–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Delferro M, Marchiò L, Tegoni M, Tardito S, Franchi-Gazzola R, Lanfranchi M, Synthesis, structural characterisation and solution chemistry of ruthenium(III) triazole-thiadiazine complexes, Dalton Trans (2009) 3766–3773. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [67].Groessl M, Reisner E, Hartinger CG, Eichinger R, Semenova O, Timerbaev AR, Jakupec MA, Arion VB, Keppler BK, Structure−Activity Relationships for NAMI-A-type Complexes (HL)[trans-RuCl4L(S-dmso)ruthenate(III)] (L = Imidazole, Indazole, 1,2,4-Triazole, 4-Amino-1,2,4-triazole, and 1-Methyl-1,2,4-triazole): Aquation, Redox Properties, Protein Binding, and Antiproliferative Activity, J. Med. Chem 50 (2007) 2185–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Turel I, Pečanac M, Golobič A, Alessio E, Serli B, Bergamo A, Sava G, Solution, solid state and biological characterization of ruthenium(III)-DMSO complexes with purine base derivatives, J. Inorg. Biochem 98 (2004) 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Vichai V, Kirtikara K, Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay for cytotoxicity screening, Nat. Protoc 1 (2006) 1112–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Caron-Beaudoin É, Sanderson JT, Denison MS, Effects of Neonicotinoids on Promoter-Specific Expression and Activity of Aromatase (CYP19) in Human Adrenocortical Carcinoma (H295R) and Primary Umbilical Vein Endothelial (HUVEC) Cells, Toxicol. Sci 149 (2015) 134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Sanderson JT, Seinen W, Giesy JP, van den Berg M, 2-Chloro-s-Triazine Herbicides Induce Aromatase (CYP19) Activity in H295R Human Adrenocortical Carcinoma Cells: A Novel Mechanism for Estrogenicity?, Toxicol. Sci 54 (2000) 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Di Nunzio M, Valli V, Tomás-Cobos L, Tomás-Chisbert T, Murgui-Bosch L, Danesi F, Bordoni A, Is cytotoxicity a determinant of the different in vitro and in vivo effects of bioactives?, BMC Complem. Altern. Med 17 (2017) 453–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Garle MJ, Fentem JH, Fry JR, In vitro cytotoxicity tests for the prediction of acute toxicity in vivo, Toxicol. in Vitro 8 (1994) 1303–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Joris F, Manshian BB, Peynshaert K, De Smedt SC, Braeckmans K, Soenen SJ, Assessing nanoparticle toxicity in cell-based assays: influence of cell culture parameters and optimized models for bridging the in vitro–in vivo gap, Chem. Soc. Rev 42 (2013) 8339–8359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Ni M, Chen Y, Lim E, Wimberly H, Shannon T Bailey Y. Imai, Rimm David L., Liu X. Shirley, Brown M, Targeting Androgen Receptor in Estrogen Receptor-Negative Breast Cancer, Cancer Cell 20 (2011) 119–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Valente A, Garcia MH, Marques F, Miao Y, Rousseau C, Zinck P, First polymer “ruthenium-cyclopentadienyl” complex as potential anticancer agent, J. Inorg. Biochem 127 (2013) 79–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Côrte-Real L, Matos AP, Alho I, Morais TS, Tomaz AI, Garcia MH, Santos I, Bicho MP, Marques F, Cellular Uptake Mechanisms of an Antitumor Ruthenium Compound: The Endosomal/Lysosomal System as a Target for Anticancer Metal-Based Drugs, Micros. Microanal 19 (2013) 1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Côrte-Real L, Karas B, Brás AR, Pilon A, Avecilla F, Marques F, Preto A, Buckley BT, Cooper KR, Doherty C, Garcia MH, Valente A, Ruthenium–Cyclopentadienyl Bipyridine–Biotin Based Compounds: Synthesis and Biological Effect, Inorg. Chem 58 (2019) 9135–9149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Scolaro C, Bergamo A, Brescacin L, Delfino R, Cocchietto M, Laurenczy G, Geldbach TJ, Sava G, Dyson PJ, In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of Ruthenium(II)−Arene PTA Complexes, J. Med. Chem 48 (2005) 4161–4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Renfrew AK, Phillips AD, Egger AE, Hartinger CG, Bosquain SS, Nazarov AA, Keppler BK, Gonsalvi L, Peruzzini M, Dyson PJ, Influence of Structural Variation on the Anticancer Activity of RAPTA-Type Complexes: ptn versus pta, Organometallics 28 (2009) 1165–1172. [Google Scholar]

- [81].Maurelli S, Chiesa M, Giamello E, Di Nardo G, Ferrero VEV, Gilardi G, Van Doorslaer S, Direct spectroscopic evidence for binding of anastrozole to the iron heme of human aromatase. Peering into the mechanism of aromatase inhibition, Chem. Comm 47 (2011) 10737–10739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Zhao J, Zhang D, Hua W, Li W, Xu G, Gou S, Anticancer Activity of Bifunctional Organometallic Ru(II) Arene Complexes Containing a 7-Hydroxycoumarin Group, Organometallics 37 (2018) 441–447. [Google Scholar]

- [83].Liu Y, Agrawal NJ, Radhakrishnan R, A flexible-protein molecular docking study of the binding of ruthenium complex compounds to PIM1, GSK-3β, and CDK2/Cyclin A protein kinases, J. Mol. Model 19 (2013) 371–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Mandal P, Kundu BK, Vyas K, Sabu V, Helen A, Dhankhar SS, Nagaraja CM, Bhattacherjee D, Bhabak KP, Mukhopadhyay S, Ruthenium(ii) arene NSAID complexes: inhibition of cyclooxygenase and antiproliferative activity against cancer cell lines, Dalton Trans 47 (2018) 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Weisz J, In Vitro Assays of Aromatase and Their Role in Studies of Estrogen Formation in Target Tissues, Cancer Res 42 (1982) 3295–3298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Lephart ED, Simpson ER, [45] Assay of aromatase activity, in: Methods in Enzymology, Academic Press, 1991, pp. 477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Sanderson JT, Boerma J, Lansbergen GWA, van den Berg M, Induction and Inhibition of Aromatase (CYP19) Activity by Various Classes of Pesticides in H295R Human Adrenocortical Carcinoma Cells, Toxicol. Appl. Pharm 182 (2002) 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Lenis-Rojas OA, Fernandes AR, Roma-Rodrigues C, Baptista PV, Marques F, Pérez-Fernández D, Guerra-Varela J, Sánchez L, Vázquez-García D, Torres ML, Fernández A, Fernández JJ, Heteroleptic mononuclear compounds of ruthenium(ii): synthesis, structural analyses, in vitro antitumor activity and in vivo toxicity on zebrafish embryos, Dalton Trans 45 (2016) 19127–19140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Mandrekar N, Thakur NL, Significance of the zebrafish model in the discovery of bioactive molecules from nature, Biotechnol. Lett 31 (2008) 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].MacRae CA, Peterson RT, Zebrafish as tools for drug discovery, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 14 (2015) 721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Berghmans S, Butler P, Goldsmith P, Waldron G, Gardner I, Golder Z, Richards FM, Kimber G, Roach A, Alderton W, Fleming A, Zebrafish based assays for the assessment of cardiac, visual and gut function — potential safety screens for early drug discovery, J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 58 (2008) 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Côrte-Real L, Karas B, Gírio P, Moreno A, Avecilla F, Marques F, Buckley BT, Cooper KR, Doherty C, Falson P, Garcia MH, Valente A, Unprecedented inhibition of P-gp activity by a novel ruthenium-cyclopentadienyl compound bearing a bipyridine-biotin ligand, Eur. J. Med. Chem 163 (2019) 853–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Karas BF, Côrte-Real L, Doherty CL, Valente A, Cooper KR, Buckley BT, A novel screening method for transition metal-based anticancer compounds using zebrafish embryo-larval assay and inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry analysis, J. Appl. Toxicol 39 (2019) 1173–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Albers MO, Singleton E, Yates JE, Mccormick FB, Dinuclear Ruthenium(II) Carboxylate Complexes, in: Inorganic Syntheses, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [95].Bruce M, Windsor N, Cyclopentadienyl-ruthenium and -osmium chemistry. IV. Convenient high-yield synthesis of some cyclopentadienyl ruthenium or osmium tertiary phosphine halide complexes, Aust. J. Chem 30 (1977) 1601–1604. [Google Scholar]

- [96].Alessio E, Balducci G, Calligaris M, Costa G, Attia WM, Mestroni G, Synthesis, molecular structure, and chemical behavior of hydrogen trans-bis(dimethyl sulfoxide)tetrachlororuthenate(III) and mer-trichlorotris(dimethyl sulfoxide)ruthenium(III): the first fully characterized chloride-dimethyl sulfoxide-ruthenium(III) complexes, Inorg. Chem 30 (1991) 609–618. [Google Scholar]

- [97].Dolomanov OV, Bourhis LJ, Gildea RJ, Howard JAK, Puschmann H, OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program, J. Appl. Crystallogr 42 (2009) 339–341. [Google Scholar]

- [98].Sheldrick G, A short history of SHELX, Acta Cryst. A 64 (2008) 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Sheldrick G, Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL, Acta Cryst. C 71 (2015) 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF, Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish, Dev. Dynam 203 (1995) 253–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Krieger E, Joo K, Lee J, Lee J, Raman S, Thompson J, Tyka M, Baker D, Karplus K, Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8, Proteins: Struct., Funct., and Bioinf 77 (2009) 114–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Thomsen R, Christensen MH, MolDock: A New Technique for High-Accuracy Molecular Docking, J. Med. Chem 49 (2006) 3315–3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.