Abstract

A dinuclear copper(II) complex of formula [{Cu(bipy)(bzt)(OH2)}2(μ-ox)] (1) (where bipy = 2,2′-bipyridine, bzt = benzoate and ox = oxalate) was synthesised and characterised by diffractometric (powder and single-crystal XRD) and thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) analyses, spectroscopic techniques (IR, Raman, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) and electronic spectroscopy), magnetic measurements and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The analysis of the crystal structure revealed that the oxalate ligand is in bis(bidentate) coordination mode between two copper(II) centres. The other four positions of the coordination environment of the copper(II) ion are occupied by one water molecule, a bidentate bipy and a monodentate bzt ligand. An inversion centre located on the ox ligand generates the other half of the dinuclear complex. Intermolecular hydrogen bonds and π-π interactions are responsible for the organisation of the molecules in the solid state. Molar magnetic susceptibility and field dependence magnetisation studies evidenced a weak intramolecular–ferromagnetic interaction (J = +2.9 cm−1) between the metal ions. The sign and magnitude of the calculated J value by density functional theory (DFT) are in agreement with the experimental data.

Keywords: dinuclear copper(II), ferromagnetic interaction, magnetic properties, noncovalent interaction

1. Introduction

Copper(II) complexes are interesting in coordination chemistry because of their vast applicability for bioinorganic purposes and synthesis of metallodrugs [1,2], catalysis [3,4] and magnetism [5,6]. Concerning molecular magnetism, it is known that the magnetic interaction between two or more copper(II) centres is strongly dependent on the nature of the bridging ligand that works like a magnetic exchange pathway [7,8]. Among these ligands, the oxalate ion, ox2−, for example, is well known for its capability to create adequate magnetic exchange pathways for ferro- and antiferromagnetic interactions in oligonuclear copper(II) compounds [9,10,11]. The combination of oxalate and copper(II) ions leads to a large structural variety including different nuclearities such as mononuclear [12,13], dinuclear [14,15], trinuclear [16,17], tetranuclear [17,18] and hexanuclear species [19,20] and coordination polymers [14,21]. This class of oxalate-bridged compounds is noteworthy in magnetic applications, as it may comprise many other transition metal ions such as MnII, FeII/III, CoII, NiII, CrII/III, VIV and RuII [22,23,24,25].

The dinuclear copper(II) complexes, which contain only one unpaired electron per metallic ion, are the most straightforward systems to investigate the through-ligand electron exchange mechanism from experimental and theoretical perspectives [26,27,28]. It is well known that the nature and strength of the magnetic interactions in dinuclear complexes including simple inorganic and extended organic bridging ligands such as hydroxo, azide, aromatic dicarboxylate, diamine, oxalate and related derivatives are highly dependent on the nature of the chelating terminal blocking ligands, which prevent complex polymerisation [5]. Furthermore, the variation in the spatial arrangement of terminal ligands may change the orbital overlap angle between the copper(II) and the bridging ligand, leading to different types of magnetic interactions [29,30].

Regarding oxalate-bridged copper(II) compounds, the ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic behaviour is determined by the overlap between the two magnetic orbitals. Poor overlap through oxalate leads to a weak antiferromagnetic interaction. On the other hand, if the overlap is zero, one could expect a ferromagnetic coupling [8]. Steric hindrance arising from the volume of the ancillary ligands leads to different orientations of the magnetic orbitals concerning the bridge plane, hence generating a different magnitude and nature of the magnetic interaction among the copper(II) centres [17].

Although a variety of oxalate (ox2−)-bridged copper(II) complexes can be found in the literature, just a few contain more than one bulky ligand besides the oxalate bridge. A detailed search carried out in the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [31] for oxalate-bridged copper(II) complexes with ox2– in bis-bidentate coordination mode displayed a total of 423 results, of which 86 correspond to dinuclear complexes that possess two additional ligands besides ox2–. Out of 86 structures, 66 contain pentacoordinate metal ions bound to only one type of organic ligand such as pyridine [1], 2,2′-bipyridine [11,32], phenanthroline [33,34], ethylenediamine [35], pyrazole [36,37] and imidazole [38] and their derivatives, the coordination sphere being completed by simple inorganic ions such as nitrate [39], chloride [33], hydroxide [40] and perchlorate [1], or by solvent molecules such as water [6], methanol [34], dimethylformamide [41], tetrahydrofuran [42] or acetonitrile [43]. In the 20 remaining structures, all of which have been reported more recently, the metal ions are hexacoordinate and the chemical composition of the complexes, regarding the presence of at least one organic ligand, solvent molecules and simple inorganic ions, is similar to that observed for the pentacoordinate species [8,11,14,15,44,45]. Exceptions are found when tetradentate ligands direct hexa-coordination, decreasing the need for other molecular entities to complete the coordination sphere of the copper(II) ion [46,47]. Therefore, such systems show high structural and electronic versatility, which can be modulated by an appropriate choice of ligands other than the ox2− bridge.

Herein the synthesis of a new heteroleptic oxalate-bridged copper(II) dinuclear complex [{Cu(bipy)(bzt)(OH2)}2(μ-ox)] (1) (where bipy = 2,2′-bipyridine, bzt = benzoate and ox = oxalate) is reported, in which the coordination environment of the metal ion is described as distorted octahedral with the unusual coordination of two relatively bulky ligands, a bidentate 2,2′-bipyridine and a monodentate benzoate, in addition to one water molecule. Structural correlations on how the orientation of the magnetic orbitals of the CuII ions is affected by the crystal field in 1 and the nature of magnetic interactions were investigated. We have also carried out theoretical calculations on the electronic structure and the electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) spectra to bring light into its magnetic properties.

2. Results and Discussion

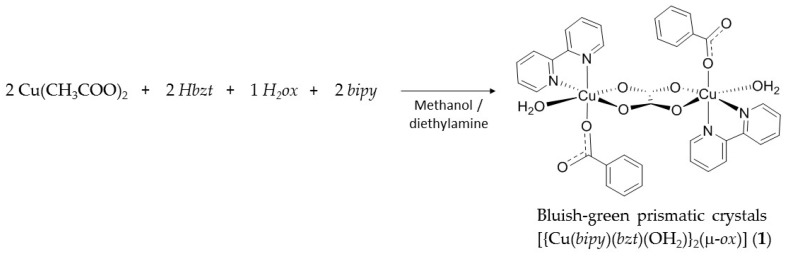

The reaction between copper(II) acetate monohydrate, benzoic acid, 2,2′-bipyridine and oxalic acid dihydrate in methanol gave the bluish-green prismatic shape crystals of [{Cu(bipy)(bzt)(OH2)}2(μ-ox)] (1) in high yield, ca 90%, from a reproducible synthetic methodology (Scheme 1). Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis revealed good correspondence between the simulated and experimental diffraction patterns (Figure S1 and Table S1).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic methodology carried out between Cu(CH3COO)2·H2O, Hbzt, H2ox·2H2O and bipy to produce complex 1. Where bipy = 2,2′-bipyridine, bzt = benzoate and ox = oxalate.

2.1. Crystal Structure

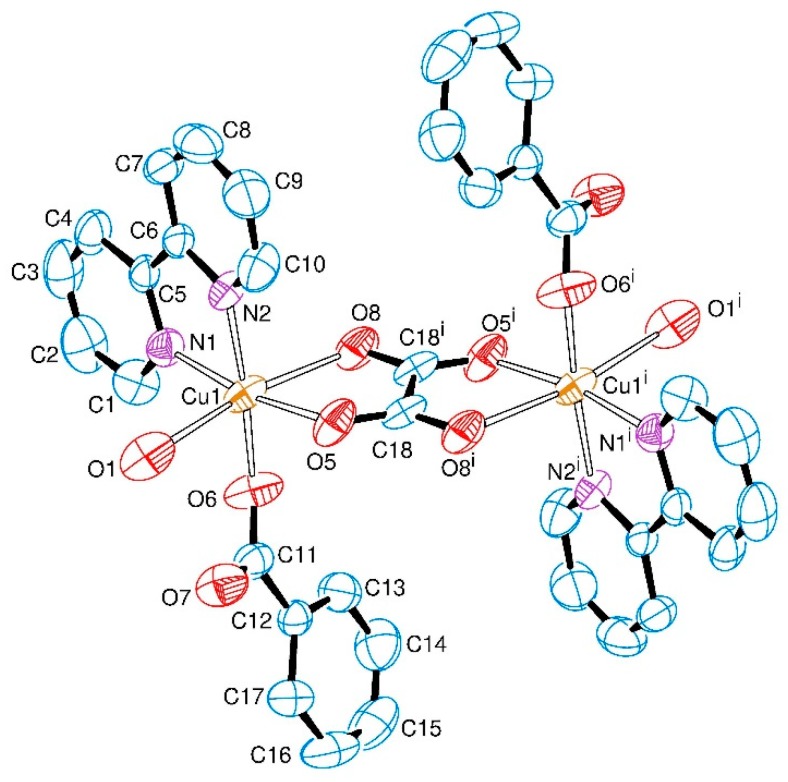

Complex 1, Figure 1, was obtained as single-crystals that belong to the centrosymmetric space group P21/n. The asymmetric unit consists of a copper(II) centre coordinated to one of each ligand molecule or ion, namely 2,2′-bipyridine, water, benzoate and one half of the oxalate bridge (the asymmetric term refers to the different C-O bond lengths in the asymmetric unit).

Figure 1.

ORTEP representation of the [{Cu(bipy)(bzt)(OH2)}2(μ-ox)] (1), indicating the atom numbering scheme. The hydrogen atoms were omitted for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Symmetry code (i): 1 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z.

The equatorial positions on each copper(II) ion are occupied by two nitrogen atoms from the 2,2′-bipyridine ligand (N1, N2), one oxygen atom from the bridging oxalate group (O5) and one oxygen atom from the monodentate benzoate ligand (O6). The apical positions are occupied by the oxygen atom from the water molecule (O1) and the second oxygen atom from the bridging oxalate group (O8). There is an inversion centre lying in the middle of the C18–C18i bond of the oxalate ligand that bridges the two copper(II) ions in the usual bis(bidentate) mode, giving rise to the neutral dimeric entity of [{Cu(bipy)(bzt)(OH2)}2(μ-ox)] as shown in Figure 1.

The coordination environment of the metal ion can be described as distorted octahedral with significant deviations exemplified by the O5–Cu1–O8 and O8–Cu1–O1 angles of 76.62(7)° and 170.00(7)°, respectively. The oxalate bridge is asymmetrically coordinated to the copper(II) centres, as indicated by the Cu1–O5 and Cu1–O8 bond lengths of 1.9732(19) and 2.378(2) Å, respectively. Equatorial Cu–N (Cu–N1 and Cu–N2) and Cu–O (Cu1–O5 and Cu–O6) distances average to 2.007(2) Å and 1.9578(19) Å, respectively, and are in good agreement with the corresponding bond lengths reported in the literature for other dimeric oxalate-bridged copper(II) complexes with the 2,2′-bipyridine ligand [6,11,32]. Due to the Jahn–Teller effect, the Cu1–O8 and the Cu1–O1 bonds are elongated (2.378(2) Å and 2.426(3) Å) in comparison to the other bond lengths in the coordination sphere of the metal in 1 (Table 1). These values are in good agreement with related tetragonally-distorted copper(II) coordination compounds that contain benzoate and/or an oxalate-bridging ligand [11,48]. The oxalate bite angle at the metal ion of 76.6° is also in accordance with other copper(II) complexes containing asymmetric oxalate bridges [8,49]. The selected geometric parameters of 1 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 1, with estimated standard deviations in parentheses.

| Bond Length (Å) | |||

| Cu(1)–O(1) | 2.426(3) | Cu(1)–N(2) | 2.006(2) |

| Cu(1)–O(5) | 1.9732(19) | O(6)–C(11) | 1.263(3) |

| Cu(1)–O(8) | 2.378(2) | O(7)–C(11) | 1.230(3) |

| Cu(1)–O(6) | 1.9425(19) | C(18)–O(5) | 1.260(3) |

| Cu(1)–N(1) | 2.008(2) | C(18) i–O(8) | 1.230(3) |

| Bond Angle (°) | |||

| O(5)–Cu(1)–O(8) | 76.62(7) | O(5)–Cu(1)–N(2) | 93.67(8) |

| O(6)–Cu(1)–O(1) | 89.46(9) | N(1)–Cu(1)–O(8) | 95.24(7) |

| O(1)–Cu(1)–O(5) | 94.26(8) | N(2)–Cu(1)–O(8) | 94.08(8) |

| O(1)–Cu(1)–O(8) | 170.00(7) | N(1)–Cu(1)–N(2) | 80.56(9) |

| O(6)–Cu(1)–O(5) | 92.77(9) | N(1)–Cu(1)–O(1) | 94.26(8) |

| O(6)–Cu(1)–O(8) | 86.93(9) | N(2)–Cu(1)–O(1) | 90.55(9) |

| O(6)–Cu(1)–N(1) | 93.00(9) | H(1B)–O(1)–H(1A) | 104(3) |

| O(6)–Cu(1)–N(2) | 173.55(9) | O(8) i–C(18)–O(5) | 124.4(2) |

| O(5)–Cu(1)–N(1) | 169.75(9) | O(7)–C(11)–O(6) | 125.7(3) |

Symmetry code (i): 1 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z.

The monodentate, rather than bidentate, coordination mode of the benzoate ion to the copper(II) centre is a remarkable feature of 1. It may be explained by its shorter Cu-N bonds lengths (ca 2.0 Å) than the equivalent ones in analogous manganese(II) [50,51] or cobalt(II) [52,53] complexes, of ca 2.2–2.3 Å and 2.1–2.2 Å, respectively. These short bonds lengths may make it difficult to accommodate bulky ligands around the copper(II) centre. The monodentate binding of bzt− is interesting since it leads to hexacoordination, a surprising result for oxalate-bridged copper(II) systems according to an extensive CSD database search. As already discussed in the Introduction, the metal ion is usually pentacoordinate when the oxalate-bridged copper(II) ions possess two additional ligands besides ox2−. Therefore, complex 1 is one of the fairly rare oxalate-bridged copper(II) complexes in octahedral coordination involving more than one bulky ligand [44,54,55,56].

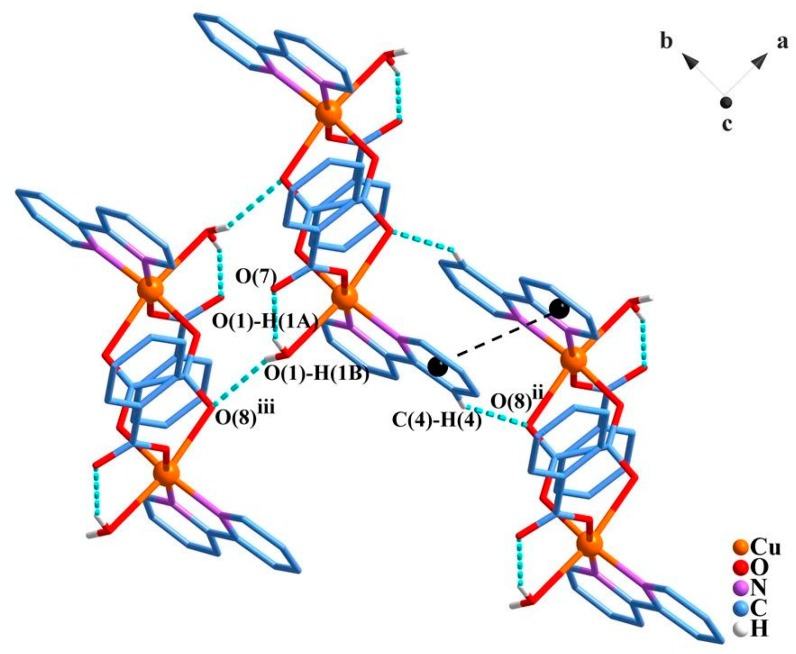

Regarding crystal packing, the centrosymmetric dimeric units are linked in a two-dimensional architecture (parallel to the a-b plane) through moderate O1–H1B…O8iii (D…A: 2.954(3) Å; D–H…A: 152(3)°; iii = x − 1, y, z) and weak C4 –H4…O8ii (D…A: 3.096(4) Å; D–H…A: 145.9°; ii = −x + 1, −y, −z + 1) hydrogen bonds (Figure 2; Table S2).

Figure 2.

Representation of the hydrogen bonds (dotted blue lines) and π-π stacking (dotted black lines) between the bipy ligands with centroids represented by black spheres. The hydrogen atoms which do not perform hydrogen bonds were omitted for clarity. Symmetry codes: (ii) –x + 1, −y, −z + 1; (iii) x − 1, y, z. The molecules shown were taken into account for the evaluation of the intermolecular magnetic interactions by density functional theory (DFT) methods.

Further, intermolecular π···π stacking interactions are observed between intercalated aromatic rings of the bipy ligands, building layers that are parallel to the crystallographic a-b plane with distances between centroids of 3.7–3.8 Å (Figure 2), and between overlapping atoms of 3.426 and 3.430 Å for C3…C9iv (iv = −x, −y, 1 − z) and C4…C6ii. Additionally, intramolecular hydrogen bonds, O1 –H1A…O7, are observed between the non-coordinated benzoate oxygen atom and a hydrogen atom from the coordinated water molecule (D…A: 2.723(3) Å; D–H···A: 153(3)°).

The intermolecular interactions are crucial for the crystal packing and organisation observed of the molecules in the solid state. The Cu1···Cu1i (i = 1 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z) distance within the dimer is 5.602 Å, whereas the shortest intramolecular Cu···Cu distance is 5.888 Å for Cu1···Cu1ii, and occurs along the a axis. The intramolecular Cu···Cu contact is significantly longer than corresponding distances in related dimeric oxalate-bridged copper(II) species with bipy ligands, which present values in the range of 5.13–5.17° [11,14,45,48,57]. Finally, the copper(II) centres are displaced 0.01 Å from the principal mean plane formed by the O1, N1, O8, C18 and O5 atoms and their symmetry equivalents.

2.2. Thermal Analysis

In order to investigate the thermal stability of 1, the complex was submitted to thermogravimetric (TG) and differential thermogravimetric (DTG) analyses with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 under N2/O2 flow. The TG/DTG curves and the attribution of each decomposition step are shown in Figure S2 and Table S3, respectively. The thermal profile obtained for 1 shows three significant decomposition steps: in the first step, a mass loss of 5.6% refers to both coordinated water molecules (calc. 4.5%) in the range of 55–136 °C, followed by a second loss with a shoulder at 210 °C that suggest full decomposition of the complex. However, from the found and calculated mass contents it was not possible to distinguish which ligand was lost in these two final steps, although one would expect bzt− to leave the complex first when compared to bipy and ox2− due to the chelate effect [58,59]. The found and calculated values for the loss of bzt− and bipy ligands in step II, 62.5% and 68.9%, respectively, may indicate that their decomposition process continues to decompose in step III, which, in turn, starts at 305 °C. The weight loss observed for ox2− (15.3%), considered here the last ligand lost in step III, is above the calculated content of 10.9%, and this could correspond to ox2− being lost together with the remaining mass of bzt− and/or bipy.

Considering the final mass content at 900 °C, which corresponds to experimental and calculated total mass losses of 84.3% and 83.4%, respectively, one infers that the complex was decomposed generating CuO as the final product (experimental 16.4%; calculated 15.8%). This obtained oxide was confirmed by powder XRD of a sample of 1 treated at 900 °C, as shown in Figure S3.

2.3. Vibrational Spectroscopy

A comparative IR study of 1 and its starting materials is presented in Figure S4 and Table S4. The spectrum of 1 indicates deprotonation of both the benzoic and oxalic acids according to the quenching of the vibrational modes at 1424 cm−1, δ(COH)COOH, and 936 cm−1, β(OH)COOH, for Hbzt, and also at 1264 cm−1 for δ(OH)COOH in H2ox. The binding of the O-donor ligands to the copper(II) centre is additionally evidenced by the shift of the absorption bands to lower frequency, from 1685–1689 to 1648 cm−1, attributed to νas(CO) for H2ox and Hbzt, respectively. The arisal of an absorption band at 1379 cm−1, assigned to νas(CO)COO−, also indicates the coordination of the bzt− and ox2− ligands [58,60,61,62]. The intense and broadened bands assigned as ν(OH) for the coordinated water molecules confirm the occurrence of hydrogen bonds (O1-H1B···O8ii and O1-H1A···O7, Figure 2 and Table S2) in 1 [61].

The Raman spectrum recorded for 1 (Figure S5 and Table S5) is in accordance with the infrared analysis as far as the incorporation of the three ligands is concerned: bands at 366-619 cm−1, assigned to νs(Cu-O) and νs(Cu-N), were observed and indicate the coordination of bipy, ox2− and bzt− [63].

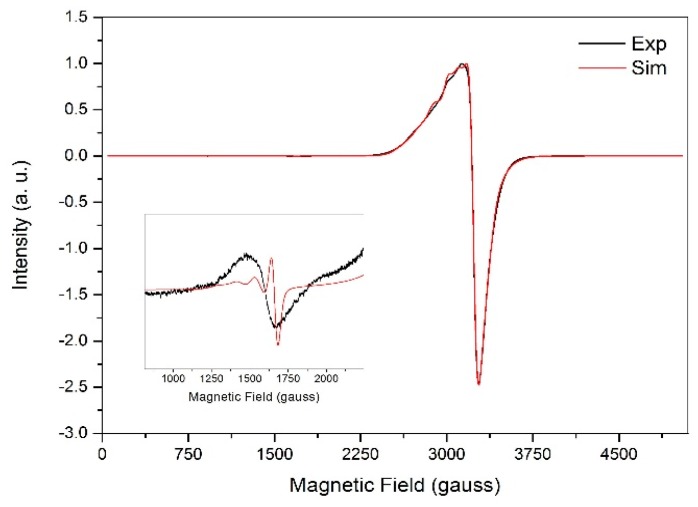

2.4. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (EPR)

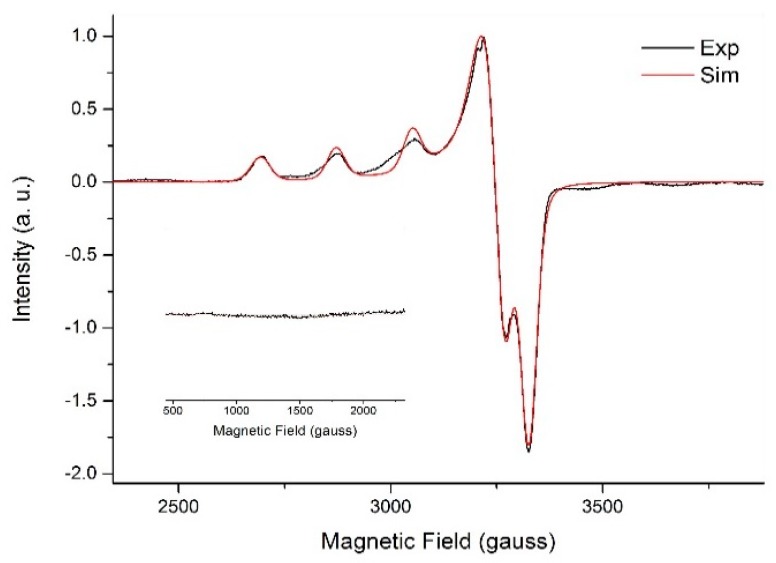

The X-band EPR spectrum recorded for polycrystalline 1 (ground crystals) at 77 K, along with simulation (parameters in Table 2), gives an axial profile with g⊥ = 2.09 and g|| = 2.26, as presented in Figure 3. These values are expected for tetragonally-distorted copper(II) complexes with elongation along the z-axis, which is in good agreement with the longest bonds in the complex [Cu(1)–O(1), 2.425(3) Å; Cu(1)–O(8), 2.378(2) Å]. The computed g-values at DFT level (g⊥ = 2.06 and g|| = 2.21) are in excellent agreement with the experiment. The g⊥ < g|| relationship indicates as the singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO), as suggested by the crystal structure [64,65]. The broadness of the EPR signal centred at 3230 G, which is due to the allowed transitions with ΔMs = ±1, agrees with the presence of magnetic interaction between the copper(II) centres in the dimer. The very weak half-field signal for the ΔMs = ±2 transitions, characteristic of copper(II) dimeric compounds with exchange interaction between the metal centres, is also observed as shown in the inset of Figure 3. Such transitions cannot be observed in S = 1/2 spin systems, being an irrefutable proof of the dimer formation in this particular case. The simulated axial zero field splitting (ZFS) parameter, D, translates to a Cu···Cu distance of 6.35 Å, which, considering the uncertainty introduced by the non-resolved hyperfine couplings, correlates well to the crystallographic Cu···Cu distance of 5.60 Å.

Table 2.

EPR spectrum simulation parameters for the frozen solution and solid powder spectra at 77 K.

| Sample | g-Matrix | A-Matrix/MHz | D-Matrix/MHz | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gx | gy | gz | Ax | Ay | Az | D | E | |

| Solid | 2.079 | 2.079 | 2.278 | <100 | <100 | >360 | 350 | 65.5 |

| Frozen solution | 2.053 | 2.078 | 2.262 | <100 | <100 | 555.1 | - | - |

Figure 3.

X-band EPR spectra for solid 1 (ground crystals) at 77 K with amplification (inset) for the half-field transition. Experimental spectrum in black and simulated spectrum in red.

The frozen solution X-band EPR spectrum of 1 was recorded at 77 K in H2O/glycerol (9:1). It is also axial with gx, gy (2.05 and 2.08) < gz (2.26). These values are again in agreement with those reported for axial copper(II) complexes containing coordinated ox2− or water [66,67]. The four-line hyperfine structure is observed in Figure 4, and arises from the interaction between the unpaired electron of copper(II) (S = 1/2) and its nuclear spin (I = 3/2) [68].

Figure 4.

X-band EPR spectra recorded for 1 in frozen H2O/glycerol 9:1 (3.0 mmol L−1) solution at 77 K with amplification (inset) evidencing the lack of a half-field transition. Experimental spectrum in black and simulated spectrum in red.

The lack of a half-field transition, according to the inset in Figure 4, indicates that the dimeric structure of 1 is not maintained in solution. This proposition is corroborated by the simulated spectrum (red line in Figure 4, simulation parameter in Table 2), which was generated for a corresponding, hypothetical mononuclear complex in solution.

The proposition of possible structures for the mononuclear complexes formed in solution is difficult given the presence of four different ligands in equal proportion—this raises the possibility of a variety of different structures. Despite this possible structural variety, it is interesting to note that slow evaporation of the EPR solution of complex 1 (3.0 mmol L−1) leads to its regeneration as verified by the unit cell analysis of the resulting crystals.

2.5. UV/Vis Spectroscopy

The electronic spectra recorded for 1 in aqueous solutions of different concentrations, Figure S6, show a broad asymmetric band at 650–750 nm that can be attributed to d-d transitions in d1 centres. The assignment of the energy states involved in these transitions is difficult due to the lack of information about the structures and, therefore, the symmetries of the mononuclear complexes formed in solution, as suggested by EPR spectroscopy. Besides the d-d transitions, the electronic spectra show intense, higher energy bands below 310 nm which may be assigned to ligand-to-metal charge transfer and/or intra-ligand transitions [17,58,69].

2.6. Magnetic Properties and ab Initio Calculations

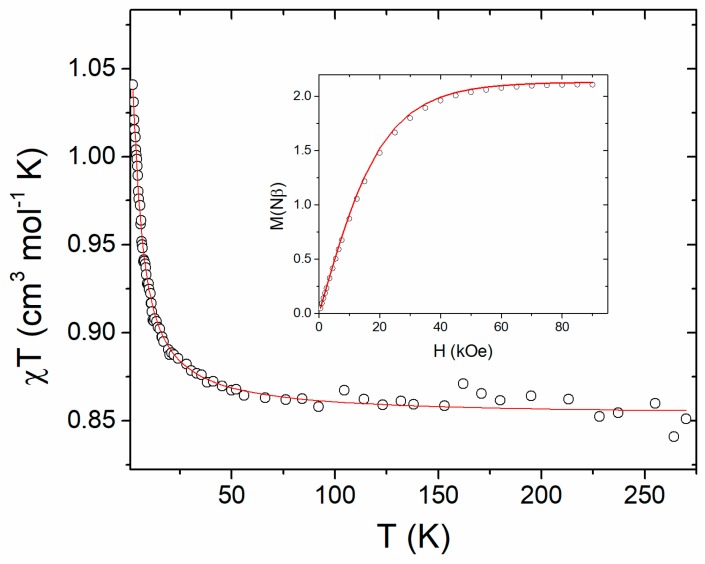

The χMT vs. T curve of 1, as well as its field-dependent magnetisation at 2.0 K from a polycrystalline sample are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

χMT vs. T and M vs. H at 2.0 K (inset) for 1. The solid lines correspond to the calculated curves using the best fit parameters described in the text.

The χMT versus T plot shows that, in the high temperature range (50 < T < 280 K), χMT is nearly constant (ca. 0.87 cm3 K mol−1), which is in good agreement with the calculated value (0.85 cm3 K mol−1) considering two copper(II) ions with g = 2.13, as obtained by simulation of the EPR spectra and by ab initio calculations. Upon cooling, there is a gradual increase of χMT, reaching a maximum value of 1.04 cm3 K mol−1 at 2.8 K, which gives support to the existence of a ferromagnetic interaction.

Due to the dimeric nature of 1, the magnetic susceptibility data were analysed considering an intramolecular magnetic interaction using the Hamiltonian H = −JS1.S2, with S1 = S2 = 1/2. The magnetic susceptibility data were fitted using the DAVE software [70]. The best-fit parameters used were the average g-value = 2.14 and the magnetic exchange interaction (J = 2.3 cm−1), confirming that the magnetic exchange interaction between the two magnetic copper(II) ions through the oxalate bridge is weak and ferromagnetic.

The intermolecular through-bond and through-space magnetic interactions were initially neglected. However, since the intermolecular interactions are mediated by hydrogen bonds between water molecules and the oxalate bridge, and by π ·· π interactions between bipyridines, we have verified that the eventual through-bond magnetic interactions are either absent or of lower orders of magnitudes. Therefore, we chose the two pairs of molecules where the closest CuII ions lie at 5.88 and 7.22 Å, respectively (see Figure 2, Section 2.1 and Section 3.4). The computed magnetic-coupling constants for the two pairs are antiferromagnetic, and their values are 0.092 and 0.085 cm−1 for the first and second pair, respectively. The strength of these intermolecular interactions is one order of magnitude lower than the intramolecular one. However, such a value cannot be neglected and, therefore, it was included in the fit. In order to prevent over-parametrisation, the intermolecular magnetic interaction was obtained considering the mean field approximation and was fixed to the value obtained from DFT calculation while the magnetic exchange interaction and average g-value were allowed to vary. The best fit parameters obtained were J = 2.9 cm−1, average g-value = 2.13 and intermolecular magnetic interaction λ = −0.09 cm−1 (fixed) (Figure 5). The agreement factor R, defined as R = Σ[(χMT)obs − (χMT)cal]2 / Σ[(χMT)2obs, is equal to 1.8 × 10−5, and is affected by the noisier data for temperatures above 60 K; otherwise, at lower temperatures, the fitting is very good. The inset of Figure 5 shows the field-dependent magnetisation at 2.0 K and the simulated curve using the same Hamiltonian and parameters as the fit of χT vs. T, confirming the intramolecular ferromagnetic interaction. The dipolar through-space magnetic interactions have also been evaluated for the CuII ion considering all the magnetic centres in the crystal packing, which are less than 20 Å away from the centre. The interactions were computed using the method described by Bencini and Gatteschi, employing the directions and values of the computed ab initio g-tensor [71]. The isotropic part of such computed magnetic exchange is 0.00019 cm−1, four orders of magnitude lower than the intramolecular one, and three orders of magnitude lower than the through-bond intermolecular one. As a consequence, unlike the through-bond exchange, the dipolar interaction was not included in the fits.

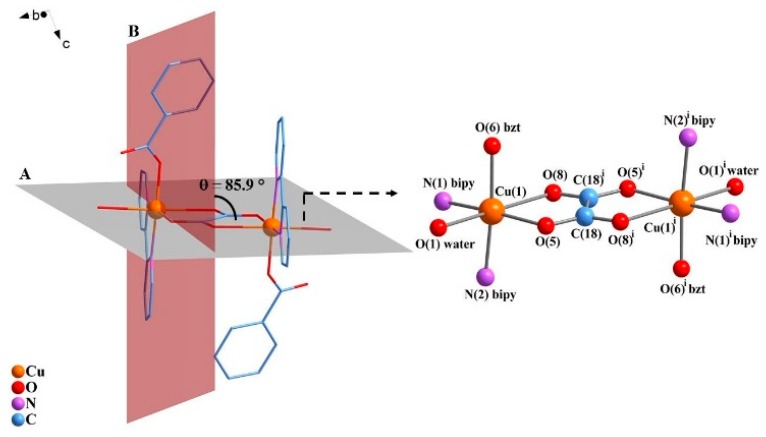

Symmetry considerations applied to the magnetic orbitals of the copper(II) centres help to understand the nature of the magnetic interactions in 1. Structural parameters, such as the Cu···Cu distance (dCu···dCu) across the bridging oxalate, the distance between the copper(II) ions and the plane described by oxygen and carbon atoms of the oxalate group, and the dihedral angle (θ) between the plane of the containing the bridging oxalate and the equatorial plane of the copper(II) complex, significantly influence the nature and the magnitude of the magnetic interactions. All these data can be useful in predicting the nature of the magnetic exchange [8,9,10,72]. For oxalate-bridged copper(II) compounds it is well known, both from experiments and theoretical calculations, that if the symmetry-related magnetic orbitals are orthogonal to the oxalate-bridge, the compound can exhibit a weak ferromagnetic interaction. In 1, the plane of the bridging oxalate ion is formed by O(5), O5i, O8, O8i, C18 and C18i (plane A in Figure 6). So, according to the magnetic data, the magnetic orbitals were expected to be located in the plane formed by O5 from ox2−, O6 from bzt− and N1 and N2 from bipy (plane B in Figure 6). In this case, the magnetic orbitals for both copper(II) centres would be parallel to each other and almost orthogonal to the oxalate bridge, the so-called ‘accidental orthogonality’, with a dihedral angle of approximately 86°, as reported for other ferromagnetic oxalate-bridged copper(II) dinuclear complexes (Table 3) [8].

Figure 6.

Representation of the dihedral angle (θ) between plane A, which contains the ox2− bridge, and plane B, which contains the orbitals. Hydrogen atoms were omitted for clarity. Symmetry code (i): 1 − x, 1 − y, 1 − z.

Table 3.

Selected magnetostructural parameters for oxalate-bridged copper(II) complexes.

| Compound (a) | dCu⋅⋅⋅Cu (Å) (b) | θ (°) (c) | α (°) (d) | J (cm−1) (e) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [{Cu(bipy)(bzt)(OH2)}2(μ-ox)] | 5.60 | 85.9 | 107.7 | +2.3 | Complex 1 |

| [{Cu(dpyam)2}2(μ-ox)](BF4)2·3H2O | 5.74 | 86.1 | - | +3.38 | [44] |

| [{Cu(dpyam)2}2(μ-ox)](ClO4)2·3H2O | 5.75 | 77.0 | - | +2.42 | [44] |

| [{Cu(prbipy)}2(μ-ox)]·4H2O | 5.46 | 78.7 | 107.4 | +3.22 | [9] |

| [{Cu(bpca)(H2O)}2(μ-ox)]·2H2O | 5.63 | 80.7 | 106.8 | +1.1 | [7] |

| [{Cu(bpca)}2(μ-ox)] | 5.44 | 86.3 | 107.4 | +1.0 | [7,49] |

| [{Cu(bpcam)(H2O)}2(μ-ox)] | 5.68 | 81.6 | 106.6 | +0.75 | [8] |

| [{Cu(dien)}2(μ-ox)](NO3)2 | 5.14 | 4.6 | 110.2 | −6.5 | [45] |

| [{Cu(3-ampy)}2(μ-ox)]n | 5.46 | 4.8 | 111.0 | −1.3 | [10] |

| [{Cu(4-ampy)}2(μ-ox)]n | 5.66 | 2.4 | 109.7 | −1.1 | [10] |

(a) Ligand abbreviations: ox = oxalate, bipy = 2,2′-bipyridine; bzt = benzoate; prbipy = N-(2-pyrazinyl)-4,4′-bipyridinium; bpca = bis(2-pyridylcarbonyl)amidate; bpcam = bis(2-pyrimidyl)amidate; dpyam = (di-2-pyridylamine); dien = diethylenediamine; ampy = aminopyridine. (b) Distance between copper(II) centres mediated by the oxalate bridge. (c) Dihedral angle between the oxalate plane and the plane containing the magnetic orbital of the complex. (d) Cu−Oaxial−Cox bond angle measured only when the oxalate is asymmetrically coordinated. (e) Magnetic coupling parameter.

There is also a reported correlation between the Cu–Oaxial–Cox bond angle (α) and the nature of the magnetic interaction for oxalate-bridged copper(II) complexes that present weak magnetic interaction. For α < 109.5°, it is highly probable that the magnetic interaction will be ferromagnetic. On the other hand, if α > 109.5°, the magnetic interaction will most likely be antiferromagnetic [8,9]. For 1, the asymmetrical coordination of the oxalate ligand is assured by the bond lengths Cu1–O5 and Cu1–O8axial of 1.973(18) and 2.378(2) Å, respectively, and the value of the α angle, given by Cu1–O8axial–C18i, is equal to 107.7 ° Based on this discussion, the comparison of the values of dCu···dCu, θ and α for complexes similar to 1 that exhibit weak ferro- or antiferromagnetic exchange interactions, as determined by temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility measurements, are shown in Table 3. These structural parameters were obtained from structures reported in the literature as Crystallographic Information Files (CIF files) using Mercury software [73]. The weak magnetic interaction determined for 1 is in the same range reported for other binuclear complexes with this type of structural arrangement.

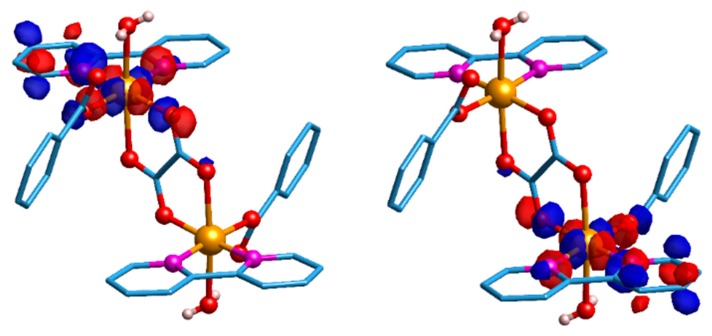

To give support to these magnetic orbital symmetry considerations, DFT calculations were performed using ORCA 4.0.1 software [74]. The magnetic orbitals are sharply localised and the local character is confirmed for each copper ion (see Figure 7). Indeed, they are parallel to each other, but perpendicular to the oxalate plane for both broken symmetry (BS) magnetic orbitals. Smaller values of electron density cut-off (≤0.05 e−/a03) evidenced a small amount of delocalisation on the second magnetic centre. However, such a delocalised density corresponds to a orbital, which, being orthogonal to the local orbital, may lead to a ferromagnetic pathway (see Figure S7) [75]. The calculations have also shown that the spin density computed on each of the copper(II) centres is essentially the same, as expected from molecular symmetry considerations. The theoretically predicted J value of +7.72 cm−1 is of the correct sign and order of magnitude, and therefore is in good agreement with the experimental J value, +2.9 cm−1, confirming that the ferromagnetic interaction is weak.

Figure 7.

Graphic representation of the two empty broken symmetry (BS) magnetic orbitals for complex 1 (left panel, spin-up; right panel, spin-down). The electron density iso value was set to 0.04 e/(a0)3. Light-blue: carbon; white: hydrogen; red: oxygen; orange: copper; pink: nitrogen.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Physical Measurements

All chemicals and solvents were used as acquired, without further purification. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Luis, MO, USA) and Merck (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) (purity grade: 99.5%) and solvents from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Luis, MO, USA) (purity grade: 98.8%–99.0%). Elemental (C, H, N) analyses were performed on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Flash EA CHNS-O 1112 series element analyser (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Copper dosage was performed on an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (GBC Scientific Equipment Pty Ltd, Hampshire, IL, USA), GBC Avanta, equipped with a flame atomiser. The crystalline phase purity of the sample was examined by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) using a Shimadzu XRD-6000 diffractometer (Shimadzu Industrial Systems Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) in a 2θ range of 10–60°. The voltage and current applied were 40 kV and 30 mA. The simulated diffractogram was performed using Mercury software [73] from the data in the CIF file of 1. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded with a BIORAD FTS 3500GX spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratory, Hercules, CA, USA) from KBr pellets in the range of 400–4000 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 in 32 scans. The Raman spectrum was recorded with a Renishaw Raman image spectrophotometer (Renishaw Plc., New Mills, United Kingdom) coupled with a Leica optical microscope in the range of 100–4000 cm−1; a He-Ne laser (632.8 nm) was employed. The analysed area of the sample was of 1 μm2 with an applied voltage of 0.2 mW. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements were carried out in the solid-state (powdered crystals) and in solution (3.0 mmol L−1 in H2O/glycerol 9:1) using an X-band Bruker ELEXSYS MX-micro spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) operating at 9.5 GHz. Simulations were carried out with the EasySpin software package [76]. Magnetic measurements were performed on a PPMS Quantum Design magnetometer (Quantum Design North America, San Diego, CA, USA) in the temperature range of 2–300 K—the powdered sample was pressed into a pellet. Temperature dependence of magnetisation was measured with an applied external magnetic field of 1 kOe between 2–60 K and 10 kOe above 60 K. Diamagnetic corrections were made using Pascal constants [77]. Electronic spectra were recorded on a UV/Vis Varian Cary 50 spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) in the range of 190–800 nm. Thermogravimetric (TG) and differential thermogravimetric (DTG) analyses were carried out on a NETZSCHSTA 449 F3 Jupiter analyser (Netzsch, Selb, Germany); the experiment was conducted under O2/N2 (flow rate of 50 mL min−1) in the range of 20–900 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1.

3.2. Synthesis of Compound 1

A solution of benzoic acid (0.122 g, 1.00 mmol) and diethylamine (105 μL, 1.00 mmol) in 10 mL of methanol was added to a suspension of copper(II) acetate monohydrate (0.199 g, 1.00 mmol) in 40 mL of methanol at 70 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 10 min leading to a bluish-green solution, which then received the addition of a colourless mixture of oxalic acid dihydrate (0.063 g, 0.50 mmol) and diethylamine (105 μL, 1.00 mmol) in 10 mL of methanol. A light-blue solution was immediately formed and was stirred for 10 min. Finally, the addition of a light-yellow solution of 2,2′-bipyridine (0.156 g, 1.00 mmol) in 10 mL of methanol, followed by stirring for 30 min, led to a change of colour to dark-blue. Bluish-green prismatic crystals were obtained after solvent evaporation at room temperature for 36 days (0.3640 g, 90% yield based on copper(II) acetate monohydrate). Solubility: slightly soluble in water, methanol, and glycerol. Elemental analysis calculated (%) for C36H30Cu2N4O10: C 53.66, H 3.75, N 6.95, Cu 15.77; found: C 53.26, H 3.77, N 7.14, Cu 16.39. IR (KBr, cm−1, s = strong, m = medium, w = weak): ν(O-H) = 3460(m); ν(C-O, COO−) = 1648, 1379(s); ν(C=C and C=N) = 1602–1445(m, w); δ(C-H) = 1305–1019(w); β(C-H) = 779–675(m). Raman (cm−1): ν = 3054(m) (O-H); ν(CO)COO− = 1597 (s); ν(C=C and C=N) = 1597–1494(s, m); δ(CCH) = 1268(w); δ(OCO) = 843(w); ν(Cu=O and Cu=N) = 619–366(w).

3.3. X-ray Crystallographic Data Collection and Refinement

A bluish-green single crystal of 1 was mounted on a micromount-type mesh (Mitegen). The data was obtained on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer equipped with a Photon 100 CMOS detector, Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) and graphite monochromator. Diffraction data were measured at 302(2) K and processed using the APEX3 program [78]. The structure was determined by the intrinsic phasing routines in the SHELXT program [79] and refined by full-matrix least-squares methods, on F2’s using SHELXL program [80,81] in the WinGX suite [82]. The non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic thermal parameters. All hydrogen atoms were located in difference Fourier maps and were refined isotropically and freely. Molecular diagrams were prepared using ORTEP3 [82] and Mercury software [73]. The crystal data collection and refinement parameters are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Crystal data and refinement parameters for compound 1.

| Formula | C36H30Cu2N4O10 |

|---|---|

| Formula weight | 805.72 g mol−1 |

| Temperature (K) | 302(2) |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.71073 Å |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/n (equiv. to no 14) |

| Z/calculated density | 2/1.593 Mg m−3 |

| a (Å) | 7.1994(3) |

| b (Å) | 10.0894(4) |

| c (Å) | 23.1941(10) |

| β (°) | 94.385(2) |

| Unit cell volume (Å3) | 1679.83(12) |

| Absorption coefficient μ (mm−1) | 1.333 |

| F(000) | 824 |

| Crystal size (mm)/colour | 0.175 × 0.087 × 0.067/bluish-green |

| θ range (°) | 2.9–25.0 |

| h, k, l ranges | ±8, ±11, ±27 |

| Completeness to θ = 25° | 99.9% |

| Total reflections/unique reflections/Rint | 51619/2953/0.069 |

| No of parameters/restraints | 243/2 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 (GOF) | 1.037 |

| R1, wR2 (all data) b | 0.052, 0.085 |

| R1, wR2 [I > 2σ(I)] a,b | 0.033, 0.078 |

| Δρmaximum/Δρminimum(eÅ−3) | 0.29/−0.17 |

a R1 = Σ||Fo| − |Fc||(Σ|Fo|)−1; b wR2 = {Σ[w(Fo2 − Fc2)2[Σ(Fo2)2]−1}1/2.

3.4. Theoretical Methods

Density functional calculations were performed with the quantum chemistry software ORCA 4.0.1 [74]. The X-ray structure of 1 was employed without any further geometry optimisation. The PBE0 [83] hybrid exchange-correlation functional was chosen. The basis sets were: def2-TZVPP [84] on Cu, N, O and C, and def2-SVP on H. The broken symmetry (BS) approach [85] was used to extract the magnetic-coupling constants. Single point calculations on both the triplet and the broken symmetry state were performed. Hence, within the Heisenberg Hamiltonian H = −JS1·S2, the value of the exchange constant was computed within the following formula: J = −(EHS − EBS)/(2S1S2), where HS is the triplet (S = 1). Within the same approach, the intermolecular exchange interaction was also computed in two dimer models. Both models were made using two molecular units of 1, as extracted from the crystal structure—the two molecular pairs whose closest Cu ions lay at 5.88 Å and 7.22 Å away from each other, respectively. The two pairs were chosen due to their Cu···Cu distance below 10 Å. Moreover, in both molecules the first pair interacts via hydrogen bonds between the oxalate bridge and the water molecules, while the second pair interacts through π-π stacking of the bipyridine ligands (see Section 3.1), which could promote a non-negligible superexchange path via π orbital overlap. All the other Cu atoms in the crystal are at a larger distance and, as a consequence, they were neglected in a first approximation. The exchange constant was computed by converging on the quintuplet and on the singlet states, i.e., the two states that arise from the two ground triplets ferromagnetically and antiferromagnetically coupled. The g-matrix of a single copper(II) atom was also computed by DFT methods. For this purpose, one of the two copper(II) atoms of the dimer was substituted in silico for its diamagnetic equivalent zinc(II). The g-matrix was obtained within the coupled-perturbed self-consistent field (CPSCF) approach [86] as implanted in Orca.

4. Conclusions

A new dinuclear copper(II) complex was synthesised and characterised. The crystal structure showed that [[{Cu(bipy)(bzt)(OH2)}2(μ-ox)] (1) is centrosymmetric and contains two rather bulky ligands, benzoate and 2,2′-bipyridine, while the majority of the complexes of this class contain just one bulky ligand. The magnetic interaction predicted by EPR was confirmed by magnetic measurements and indicated ferromagnetic coupling between the metal centres. The determined J value was supported by DFT calculations. Therefore, the present study highlights the importance of the oxalate bridge as a magnetic-exchange pathway, and how bulky ancillary ligands can affect the magnetic response.

Acknowledgments

D.M.R. and F.S.S. acknowledge the Laboratório Multiusuário de Análises Químicas (LAMAQ, UTFPR) and M.Sc. Rubia Camila Ronqui Bottini for technical support. R.A.A.C. and D.M.R. acknowledge FAPERJ and CNPq for financial support, and D.L.H. is grateful to CAPES. Authors gratefully thank Professor Jaísa Fernandes Soares (UFPR), Professors Paola Paoli and Patrizia Rossi (Università degli Studi di Firenze) and M.Sc. Juliana Morais Missina (UFPR) for discussions and helpful suggestions. We also thank M.Sc. Ângelo Roberto dos Santos (UFPR) and Dr Siddhartha Om Kumar Giese for the TGA and EPR analyses, respectively. The authors thank Professor Luis Ghivelder and Laboratório de Baixas Temperaturas—IF-UFRJ for using the PPMS equipment.

Supplementary Materials

The following material is available online, Figure S1: Comparison between simulated and experimental PXRD patterns of complex 1 (scan velocity: 0.005° s−1), Figure S2: Thermogravimetric analysis (TG and DTG) profiles obtained for 1 in O2/N2 as carrier gas and temperature range of 20 to 900 °C, Figure S3: Comparison between simulated and experimental PXRD patterns of CuO (scan velocity: 0.005° s−1), Figure S4: Infrared spectra of 1 and its starting materials, H2ox·2H2O, Hbzt and bipy recorded from KBr pellets, Figure S5: Raman spectrum recorded for 1 with exposure time of 10 s and power at 50 % (laser: He-Ne, 632.8 nm), Figure S6: UV-Vis absorption spectra recorded for complex 1 at 3.00, 2.50, 2.00, 1.50 and 0.75 mmol L−1 in water, Figure S7: Graphic representation of the two occupied broken symmetry (BS), spin-up and spin-down, magnetic orbitals for complex 1. The electron density iso value was set to 0.04 e/(a0)3. Light-blue: carbon; white: hydrogen; red: oxygen; orange: copper; pink: nitrogen, Table S1: Values of 2θ angles for the experimental and simulated PXRD diffractograms of 1 from 10 to 30° displaying a difference of ca 0.1°, Table S2: Hydrogen bond parameters (Å, °), Table S3: Thermal data for 1, Table S4: Tentative assignments for the IR (cm−1) spectrum recorded for complex 1, Table S5: Tentative assignments for the Raman scattering (cm−1) spectrum recorded for complex 1. CCDC 1971374 contains the supplementary crystallographic data in CIF format, and this data can be obtained free of charge at http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S.S., G.G.N. and D.M.R.; formal analysis, F.S.S., M.B., R.A.A.C., R.R.R. and D.L.H.; funding acquisition, F.T., G.G.N. and D.M.R.; investigation, F.S.S., M.B., R.A.A.C. and F.T.; methodology, F.S.S.; project administration, D.M.R.; resources, R.A.A.C., F.T., G.G.N. and D.M.R.; software, M.B. and F.T.; supervision, G.G.N. and D.M.R.; writing—original draft, F.S.S.; writing—review and editing F.S.S., M.B., R.A.A.C., F.T., R.R.R., D.L.H., G.G.N. and D.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Grant n° 449460/2014-2), the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, PVE A099/2013), the Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR) and the Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná (UTFPR).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Sample of the compound 1 is available from the authors.

References

- 1.Huang K.-B., Chen Z.-F., Liu Y.-C., Xie X.-L., Liang H. Dihydroisoquinoline copper(II) complexes: Crystal structures, cytotoxicity, and action mechanism. Rsc. Adv. 2015;5:81313–81323. doi: 10.1039/C5RA15789G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Usman M., Arjmand F., Khan R.A., Alsalme A., Ahmad M., Bishwas M.S., Tabassum S. Tetranuclear cubane Cu4O4 complexes as prospective anticancer agents: Design, synthesis, structural elucidation, magnetism, computational and cytotoxicity studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2018;473:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2017.12.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanyal R., Kundu P., Rychagova E., Zhigulin G., Ketkov S., Ghosh B., Chattopadhyay S.K., Zangrando E., Das D. Catecholase activity of Mannich-based dinuclear CuII complexes with theoretical modeling: New insight into the solvent role in the catalytic cycle. New J. Chem. 2016;40:6623–6635. doi: 10.1039/C6NJ00105J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parween A., Naskar S., Mota A.J., Espinosa Ferao A., Chattopadhyay S.K., Rivière E., Lewis W., Naskar S. C i -Symmetry, [2 × 2] grid, square copper complex with the N4,N5-bis(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-imidazole-4,5-dicarboxamide ligand: Structure, catecholase activity, magnetic properties and DFT calculations. New J. Chem. 2017;41:11750–11758. doi: 10.1039/C7NJ01667K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castro I., Calatayud M.L., Yuste C., Castellano M., Ruiz-García R., Cano J., Faus J., Verdaguer M., Lloret F. Dinuclear copper(II) complexes as testing ground for molecular magnetism theory. Polyhedron. 2019;169:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2019.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutta D., Nath H., Frontera A., Bhattacharyya M.K. A novel oxalato bridged supramolecular ternary complex of Cu(II) involving energetically significant π-hole interaction: Experimental and theoretical studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2019;487:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2018.12.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calatayud M.A.L., Castro I., Sletten J., Lloret F., Julve M. Syntheses, crystal structures and magnetic properties of chromato-, sulfato-, and oxalato-bridged dinuclear copper(II) complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2000;300–302:846–854. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(99)00590-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cangussu D., Stumpf H.O., Adams H., Thomas J.A., Lloret F., Julve M. Oxalate, squarate and croconate complexes with bis(2-pyrimidylcarbonyl)amidatecopper(II): Synthesis, crystal structures and magnetic properties. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2005;358:2292–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2004.11.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng A.-L., Ju Z.-F., Li W., Zhang J. Ferromagnetic dinuclear copper(II) complex based on bridging oxalate and bipyridinium ligands. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2006;9:489–492. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2006.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castillo O., Luque A., Román P., Lloret F., Julve M. Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Magnetic Properties of One-Dimensional Oxalato-Bridged Co(II), Ni(II), and Cu(II) Complexes with n-Aminopyridine (n = 2−4) as Terminal Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:5526–5535. doi: 10.1021/ic0103401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Julve M., Gleizes A., Chamoreau L.M., Ruiz E., Verdaguer M. Antiferromagnetic Interactions in Copper(II) µ-Oxalato Dinuclear Complexes: The Role of the Counterion. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018;2018:509–516. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201700935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng L.-Y., Chi Y.-H., Liang Y., Cottrill E., Pan N., Shi J.-M. Green and mild oxidation: From acetate anion to oxalate anion. J. Coord. Chem. 2018;71:3947–3954. doi: 10.1080/00958972.2018.1543870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carranza J., Brennan C., Sletten J., Vangdal B., Rillema P., Lloret F., Julve M. Syntheses, crystal structures and magnetic properties of new oxalato-, croconato- and squarato-containing copper(II) complexes. New J. Chem. 2003;27:1775–1783. doi: 10.1039/b301212n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melnic E., Kravtsov V.C., Krämer K., van Leusen J., Decurtins S., Liu S.-X., Kögerler P., Baca S.G. Versatility of copper(II) coordination compounds with 2,3-bis(2-pyridyl)pyrazine mediated by temperature, solvents and anions choice. Solid State Sci. 2018;82:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2018.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golchoubian H., Samimi R. Solvato- and thermochromism study in oxalato-bridged dinuclear copper(II) complexes of bidentate diamine ligands. Polyhedron. 2017;128:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2017.02.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Royappa A.T., Royappa A.D., Moral R.F., Rheingold A.L., Papoular R.J., Blum D.M., Duong T.Q., Stepherson J.R., Vu O.D., Chen B., et al. Copper(I) oxalate complexes: Synthesis, structures and surprises. Polyhedron. 2016;119:563–574. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2016.09.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Świtlicka-Olszewska A., Machura B., Mroziński J., Kalińska B., Kruszynski R., Penkala M. Effect of N-donor ancillary ligands on structural and magnetic properties of oxalate copper(ii) complexes. New J. Chem. 2014;38:1611–1626. doi: 10.1039/C3NJ01541F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyazato Y., Asato E., Ohba M., Wada T. Synthesis and Characterization of a Di-µ-oxalato Tetracopper(II) Complex with Tetranucleating Macrocyclic Ligand. B. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2016;89:430–436. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.20150338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuste C., Cañadillas-Delgado L., Labrador A., Delgado F.S., Ruiz-Pérez C., Lloret F., Julve M. Low-Dimensional Copper(II) Complexes with the Trinucleating Ligand 2,4,6-Tris(di-2-pyridylamine)-1,3,5-triazine: Synthesis, Crystal Structures, and Magnetic Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:6630–6640. doi: 10.1021/ic900599g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vicente R., Escuer A., Solans X., Font-Bardía M. Synthesis, magnetic behaviour and structural characterization of the alternating hexanuclear copper(II) compound [Cu6(tmen)6(µ-N3)2(µ-C2O4)3(H2O)2][ClO4]4·2H2O (tmen = Me2NCH2CH2NMe2) J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1996;1996:1835–1838. doi: 10.1039/DT9960001835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakahata D.H., de Paiva R.E.F., Lustri W.R., Ribeiro C.M., Pavan F.R., da Silva G.G., Ruiz A.L.T.G., de Carvalho J.E., Corbi P.P. Sulfonamide-containing copper(II) metallonucleases: Correlations with in vitro antimycobacterial and antiproliferative activities. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018;187:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maxim C., Ferlay S., Train C. Binuclear heterometallic M(III)–Mn(II) (M = Fe, Cr) oxalate-bridged complexes associated with a bisamidinium dication: A structural and magnetic study. New J. Chem. 2011;35:1254–1259. doi: 10.1039/c0nj00976h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glerup J., Goodson P.A., Hodgson D.J., Michelsen K. Magnetic Exchange through Oxalate Bridges: Synthesis and Characterization of (mu-Oxalato)dimetal(II) Complexes of Manganese, Iron, Cobalt, Nickel, Copper, and Zinc. Inorg. Chem. 1995;34:6255–6264. doi: 10.1021/ic00129a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baruah B., Golub V.O., O’Connor C.J., Chakravorty A. Synthesis of Oxalato-Bridged (Oxo)vanadium(IV) Dimers Using L-Ascorbic Acid as Oxalate Precursor: Structure and Magnetism of Two Systems. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003;2003:2299–2303. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200300013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bratsos I., Serli B., Zangrando E., Katsaros N., Alessio E. Replacement of Chlorides with Dicarboxylate Ligands in Anticancer Active Ru(II)-DMSO Compounds: A New Strategy That Might Lead to Improved Activity. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:975–992. doi: 10.1021/ic0613964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adamo C., Barone V., Bencini A., Totti F., Ciofini I. On the Calculation and Modeling of Magnetic Exchange Interactions in Weakly Bonded Systems: The Case of the Ferromagnetic Copper(II) μ2-Azido Bridged Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1996–2004. doi: 10.1021/ic9812306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calzado C.J., Cabrero J., Malrieu J.P., Caballol R. Analysis of the magnetic coupling in binuclear complexes. I. Physics of the coupling. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:2728–2747. doi: 10.1063/1.1430740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calzado C.J., Cabrero J., Malrieu J.P., Caballol R. Analysis of the magnetic coupling in binuclear complexes. II. Derivation of valence effective Hamiltonians from ab initio CI and DFT calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:3985–4000. doi: 10.1063/1.1446024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Z., Thompson L.K., Miller D.O. Dicopper(II) Complexes Bridged by Single N−N Bonds. Magnetic Exchange Dependence on the Rotation Angle between the Magnetic Planes. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:3985–3995. doi: 10.1021/ic970235k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson L.K., Tandon S.S., Lloret F., Cano J., Julve M. An Azide-Bridged Copper(II) Ferromagnetic Chain Compound Exhibiting Metamagnetic Behavior. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:3301–3306. doi: 10.1021/ic970023n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groom C.R., Bruno I.J., Lightfoot M.P., Ward S.C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Cryst. 2016;B72:171–179. doi: 10.1107/S2052520616003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jurić M., Pajić D., Žilić D., Rakvin B., Milić D., Planinić P. Synthesis, crystal structures and magnetic properties of the oxalate-bridged single CuIICuII and cocrystallized CuIIZnII systems. Three species (CuCu, CuZn, ZnZn) in the crystalline lattice. Polyhedron. 2015;98:26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goswami S., Singha S., Saha R., Singha Roy A., Islam M., Kumar S. A bi-nuclear Cu(II)-complex for selective epoxidation of alkenes: Crystal structure, thermal, photoluminescence and cyclic voltammetry. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2019;486:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2018.10.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliveira W.X.C., Pereira C.L.M., Pinheiro C.B., Lloret F., Julve M. Oxotris(oxalate)niobate(V): An oxalate delivery agent in the design of building blocks. J. Coord. Chem. 2018;71:707–724. doi: 10.1080/00958972.2018.1428313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samimi R., Golchoubian H. Dinuclear copper(II) complexes with ethylenediamine derivative and bridging oxalato ligands: Solvatochromism and density functional theory studies. Transit. Met. Chem. 2017;42:643–653. doi: 10.1007/s11243-017-0170-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calatayud M.L., Orts-Arroyo M., Julve M., Lloret F., Marino N., De Munno G., Ruiz-García R., Castro I. Magneto-structural correlations in asymmetric oxalato-bridged dicopper(II) complexes with polymethyl-substituted pyrazole ligands. J. Coord. Chem. 2018;71:657–674. doi: 10.1080/00958972.2017.1421950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bahemmat S., Neumüller B., Ghassemzadeh M. One-Pot Synthesis of an Oxalato-Bridged CuII Coordination Polymer Containing an in Situ Produced Pyrazole Moiety: A Precursor for the Preparation of CuO Nano structures. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015;2015:4116–4124. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201500255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu C., Abboud K.A. Crystal structures of [mu]-oxalato-bis[azido(histamine)copper(II)] and [mu]-oxalato-bis[(dicyanamido)(histamine)copper(II)] Acta Cryst. 2015;E71:1379–1383. doi: 10.1107/S2056989015019908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Min K.S., Suh M.P. Self-Assembly, Structures, and Magnetic Properties of Ladder-Like Copper(II) Coordination Polymers. J. Solid State Chem. 2000;152:183–190. doi: 10.1006/jssc.2000.8682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hökelek T., Ünaleroğglu C., Mert Y. Crystal Structure of [Bis(N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine)-O,O’-μ-O,O’-oxalato]dihydroxy Dicopper(II) Anal. Sci. 2000;16:1235–1236. doi: 10.2116/analsci.16.1235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang W., Ogawa T. Spectral and structural studies of a new oxalato-bridged dinuclear copper(II) complex having two 3-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,10-phenanthroline ligands in a trans configuration. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2009;362:3877–3880. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2009.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thuéry P. Increasing Complexity in the Uranyl Ion–Kemp’s Triacid System: From One- and Two-Dimensional Polymers to Uranyl–Copper(II) Dodeca- and Hexadecanuclear Species. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014;14:2665–2676. doi: 10.1021/cg500353k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du M., Guo Y.-M., Chen S.-T., Bu X.-H., Ribas J. Crystal structures, spectra and magnetic properties of di-2-pyridylamine (dpa) CuII complexes [Cu(dpa)2(N3)2]·(H2O)2 and [Cu2(μ-ox)(dpa)2(CH3CN)2](ClO4)2. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2003;346:207–214. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(02)01430-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Youngme S., van Albada G.A., Chaichit N., Gunnasoot P., Kongsaeree P., Mutikainen I., Roubeau O., Reedijk J., Turpeinen U. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, X-ray crystal structure and magnetic properties of oxalato-bridged copper(II) dinuclear complexes with di-2-pyridylamine. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2003;353:119–128. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(03)00207-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castillo O., Muga I., Luque A., Gutiérrez-Zorrilla J.M., Sertucha J., Vitoria P., Román P. Synthesis, chemical characterization, X-ray crystal structure and magnetic properties of oxalato-bridged copper(II) binuclear complexes with 2,2′-bipyridine and diethylenetriamine as peripheral ligands. Polyhedron. 1999;18:1235–1245. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5387(98)00421-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gusev A.N., Nemec I., Herchel R., Bayjyyev E., Nyshchimenko G.A., Alexandrov G.G., Eremenko I.L., Trávníček Z., Hasegawa M., Linert W. Versatile coordination modes of bis [5-(2-pyridine-2-yl)-1,2,4-triazole-3-yl]alkanes in Cu(ii) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:7153–7165. doi: 10.1039/C4DT00462K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pokharel U.R., Fronczek F.R., Maverick A.W. Reduction of carbon dioxide to oxalate by a binuclear copper complex. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5883. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boyko A.N., Haukka M., Golenya I.A., Pavlova S.V., Usenko N.I. [mu]-Oxalato-bis[(2,2’-bipyridyl)copper(II)] bis(perchlorate) dimethylformamide disolvate monohydrate. Acta Cryst. 2010;E66:m1101–m1102. doi: 10.1107/S1600536810031569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castro I., Faus J., Julve M., Mollar M., Monge A., Gutierrez-Puebla E. Formation in solution, synthesis and crystal structure of μ-oxalatobis[bis(2-pyridylcarbonyl)amido] dicopper(II) Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1989;161:97–104. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)90121-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li K.-k., Zhang C., Xu W. [mu]-Oxalato-bis[bis(2,2’-bipyridine)manganese(II)] bis(perchlorate) 2,2’-bipyridine solvate. Acta Cryst. 2011;E67:m1443–m1444. doi: 10.1107/S1600536811038475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaizaki S., Nakahanada M., Fuyuhiro A., Ikedo-Urade M., Abe Y. Synthesis, characterization and redox reactivity of l-tartrato bridged dinuclear manganese complex with 2,2′-bipyridine. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2009;362:5117–5121. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2009.07.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duan W., Jiao S., Liu X., Chen J., Cao X., Chen Y., Xu W., Cui X., Xu J., Pang G. Two new supramolecular hybrids based on bi-capped Keggin {PMo12V2O42} clusters and transition metal mixed-organic-ligand complexes. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2015;31:179–186. doi: 10.1007/s40242-015-5033-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi C., Fan L., Wei P., Li B., Zhang X. (μ-Oxalato-κ4O1,O2:O1’,O2’)bis[bis(2,2’-bipyridine-κ2N,N’)cobalt(II)] μ6-oxido-dodeca-μ2-oxido-hexaoxido-hexatungstate(VI) Acta Cryst. 2010;E66:m822–m823. doi: 10.1107/S1600536810023007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Androš Dubraja L., Jurić M., Torić F., Pajić D. The influence of metal centres on the exchange interaction in heterometallic complexes with oxalate-bridged cations. Dalton Trans. 2017;46:11748–11756. doi: 10.1039/C7DT02522J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Youngme S., Gunnasoot P., Chaichit N., Pakawatchai C. Dinuclear copper(II) complexes with ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic interactions mediated by a bridging oxalato group: Structures and magnetic properties of [Cu2L4(μ-C2O4)](PF6)2(H2O)2 and [Cu2L2(μ-C2O4)(NO3)2((CH3)2NCOH)2] (L = di-2-pyridylamine) Transit. Met. Chem. 2004;29:840–846. doi: 10.1007/s11243-004-1566-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qin C. μ-Oxalato-κ2O1,O2:κ2O1’,O2’-bis[(3,5-dicarboxybenzoato-κ2O1,O1’)(1,10-phenanthroline-κ2N,N’)copper(II)] Acta Cryst. 2007;E63:m1006–m1007. doi: 10.1107/S1600536807009828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Faria D.M., Yoshida M.I., Pinheiro C.B., Guedes K.J., Krambrock K., Diniz R., de Oliveira L.F.C., Machado F.C. Preparation, crystal structures and spectroscopic characterization of oxalate copper(II) complexes containing the nitrogen ligands 4,4′-dimethyl-2,2′-bipyridine and di(2-pyridyl)sulfide. Polyhedron. 2007;26:4525–4532. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2007.06.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Androš L., Jurić M., Planinić P., Žilić D., Rakvin B., Molčanov K. New mononuclear oxalate complexes of copper(II) with 2D and 3D architectures: Synthesis, crystal structures and spectroscopic characterization. Polyhedron. 2010;29:1291–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2010.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sarma R., Boudalis A.K., Baruah J.B. Aromatic N-oxide bridged copper(II) coordination polymers: Synthesis, characterization and magnetic properties. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2010;363:2279–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2010.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stepanian S.G., Reva I.D., Radchenko E.D., Sheina G.G. Infrared spectra of benzoic acid monomers and dimers in argon matrix. Vib. Spectrosc. 1996;11:123–133. doi: 10.1016/0924-2031(95)00068-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silverstein R.M., Webster F.X., Kiemle D.J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. 7th ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakamoto K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds—Part B: Applications in Coordination, Organometallic, and Bioinorganic Chemistry. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edwards H.G.M., Farwell D.W., Rose S.J., Smith D.N. Vibrational spectra of copper (II) oxalate dihydrate, CuC2O4·2H20, and dipotassium bis-oxalato copper (II) tetrahydrate, K2Cu(C2O4)2·4H2O. J. Mol. Struc. 1991;249:233–243. doi: 10.1016/0022-2860(91)85070-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Halaška J., Pevec A., Strauch P., Kozlevčar B., Koman M., Moncol J. Supramolecular hydrogen-bonding networks constructed from copper(II) chlorobenzoates with nicotinamide: Structure and EPR. Polyhedron. 2013;61:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2013.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Godlewska S., Jezierska J., Baranowska K., Augustin E., Dołęga A. Copper(II) complexes with substituted imidazole and chlorido ligands: X-ray, UV–Vis, magnetic and EPR studies and chemotherapeutic potential. Polyhedron. 2013;65:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2013.08.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vicente R., Escuer A., Ferretjans J., Stoeckli-Evans H., Solans X., Font-Bardía M. Structurally alternating copper(II) chains from oxalate and azide bridging ligands: Syntheses and crystal structure of [Cu2(µ-ox)(deen)2(H2O)2(ClO4)2] and [{Cu2(µ-N3)(µ-ox)(deen)2}n][ClO4] n (deen = Et2NCH2CH2NH2) J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1997;1997:167–172. doi: 10.1039/a604692d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Recio A., Server-Carrió J., Escrivà E., Acerete R., García-Lozano J., Sancho A., Soto L. Novel Cu(II)-Based Frameworks Built from BIMAM and Oxalate: Syntheses, Structures, and Magnetic Characterizations (BIMAM = Bis(imidazol-yl) methylaminomethane) Cryst. Growth Des. 2008;8:4075–4082. doi: 10.1021/cg800514f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Halcrow M.A. Interpreting and controlling the structures of six-coordinate copper(II) centres—When is a compression really a compression? Dalton Trans. 2003:4375–4384. doi: 10.1039/B309242A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yilmaz V.T., Hamamci S., Andac O., Thöne C., Harrison W.T.A. Mono- and binuclear copper(II) complexes of saccharin with 2-pyridinepropanol synthesis, spectral, thermal and structural characterization. Transit. Met. Chem. 2003;28:676–681. doi: 10.1023/A:1025437507627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.zuah R.T., LR K., Qiu Y., Tregenna-Piggott P.L.W., Brown C.M., Copley J.R.D., Dimeo R.M. DAVE: A comprehensive software suite for the reduction, visualization, and analysis of low energy neutron spectroscopic data. J. Res. Nat. Inst. Stan. 2009;114:341–358. doi: 10.6028/jres.114.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bencini A., Gatteschi D. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance of Exchange Coupled Systems. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Germany: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pal P., Konar S., El Fallah M.S., Das K., Bauzá A., Frontera A., Mukhopadhyay S. Synthesis, crystal structures, magnetic properties and DFT calculations of nitrate and oxalate complexes with 3,5 dimethyl-1-(2′-pyridyl)-pyrazole-Cu(ii) Rsc Adv. 2015;5:45082–45091. doi: 10.1039/C5RA04241K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Macrae C.F., Bruno I.J., Chisholm J.A., Edgington P.R., McCabe P., Pidcock E., Rodriguez-Monge L., Taylor R., van de Streek J., Wood P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0—new features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures. J. App. Cryst. 2008;41:466–470. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807067908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neese F. The ORCA program system. Wires Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012;2:73–78. doi: 10.1002/wcms.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bencini A., Totti F., Daul C.A., Doclo K., Fantucci P., Barone V. Density Functional Calculations of Magnetic Exchange Interactions in Polynuclear Transition Metal Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:5022–5030. doi: 10.1021/ic961448x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stoll S., Schweiger A. EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 2006;178:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kahn O. Molecular Magnetism. VCH; New York, NY, USA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Program APEX3. Bruker AXS Inc.; Madison, WI, USA: 2015. [(accessed on 16 April 2020)]. Available online: https://www.bruker.com/products/x-ray-diffraction-and-elemental-analysis/single-crystal-x-ray-diffraction/sc-xrd-software/apex3.html. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sheldrick G. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015;A71:3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sheldrick G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. 2015;C71:3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sheldrick G. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. 2008;A64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farrugia L. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An update. J. App. Cryst. 2012;45:849–854. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812029111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Adamo C., Barone V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;110:6158–6170. doi: 10.1063/1.478522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weigend F., Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Phys. 2005;7:3297–3305. doi: 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bencini A., Totti F. A Few Comments on the Application of Density Functional Theory to the Calculation of the Magnetic Structure of Oligo-Nuclear Transition Metal Clusters. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:144–154. doi: 10.1021/ct800361x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Neese F. Efficient and accurate approximations to the molecular spin-orbit coupling operator and their use in molecular g-tensor calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;122:034107. doi: 10.1063/1.1829047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.