Abstract

This cohort study examines a process of digitized informed consent for the enrollment of a rural population in research.

Rural and minority populations are underrepresented in clinical research, likely because of travel barriers and financial resources required to participate in conventional studies.1 Digital technology holds promise to improve access to clinical studies,2 but limited evidence is available detailing the adoption of these methods in underserved populations. We describe our experience using digital technology for remote enrollment in a clinical study evaluating the use of home blood pressure (BP) telemonitoring for hypertension management.

Methods

This prospective study at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) used data for participants enrolled from September 4, 2018, through September 19, 2019. The study protocol was approved by the UMMC institutional review board. Adult patients with hypertension and uncontrolled BP who were receiving outpatient care at UMMC were eligible for study inclusion.

Potential participants were identified by referral and review of the electronic health record. Following a screening telephone call, interested individuals meeting eligibility criteria were mailed a telemonitoring kit, including an electronic tablet with prepaid secure broadband connectivity, wireless BP cuff, and institutional review board–approved consent document. There were no costs incurred by study participants. The consent document was written at an eighth-grade reading level using lay terminology and formatted to facilitate clear understanding of the content. After receiving the kit, the research coordinator (K.J.) contacted the participant via the tablet for an audiovisual encounter. During the audiovisual encounter, personal identifying information was confirmed and the consent form reviewed, with the ability to screen-share the document in real time. The research coordinator, who was well versed in the cultural exigencies of this patient population, addressed any questions or concerns. Informed consent was authorized by the participant by agreeing to a confirmatory statement displayed on the tablet, which generated a time and date electronic stamp transmitted to the individual’s electronic health record. The research coordinator documented the encounter in the electronic health record, including a description of the consent process. If the individual declined to participate, the kit was returned at no cost to the participant in a prepaid shipping box. Data analysis was completed with Excel version 16.0.12624 (Microsoft).

Results

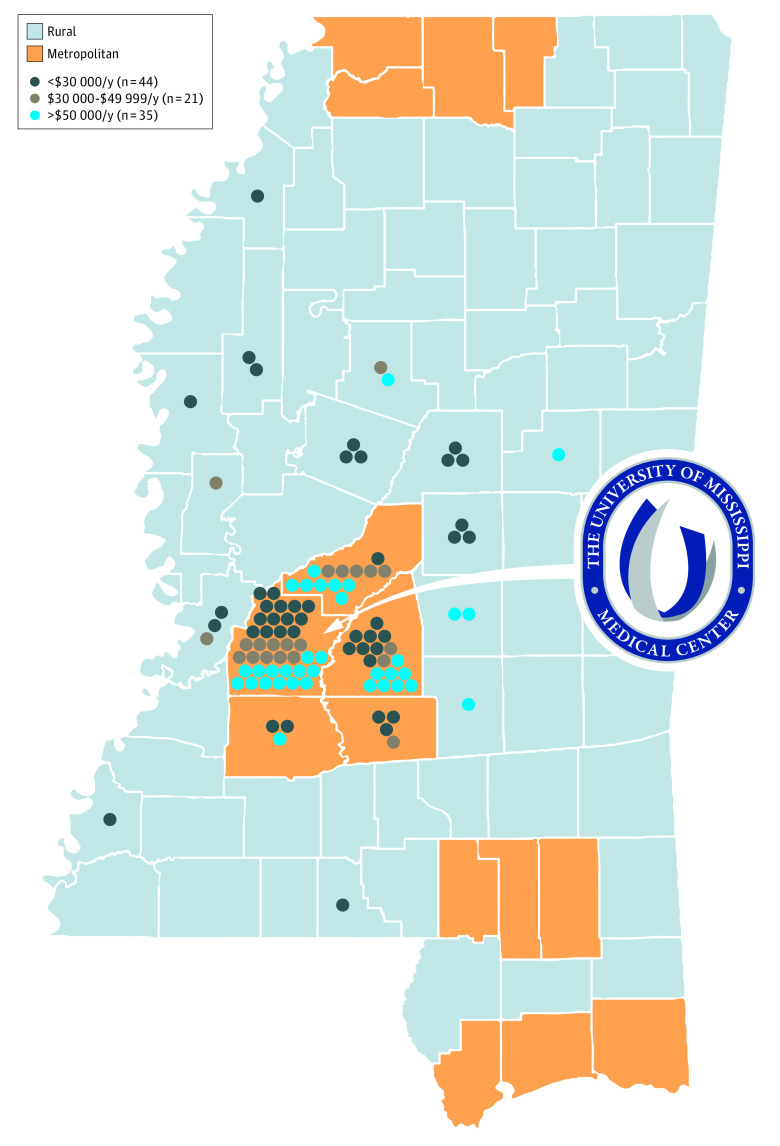

Among 100 enrolled participants, the mean (SD) age was 59.6 (11.1) years; 54 participants (54%) were female, and 45 (45%) were African American (Table). Twenty-three participants (23%) resided in a rural county, and 43 (43%) reported household income of less than $30 000 per year (Figure). Ten participants (10%) provided informed consent during a work break. Two participants were unable to complete enrollment because of insufficient device connectivity.

Table. Characteristics of Research Participants.

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| No. | 100 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 59.6 (11.1) |

| Female | 65 (65) |

| African American | 54 (54) |

| Insurance status | |

| Private | 51 (51) |

| Medicare | 32 (32) |

| Medicaid | 13 (13) |

| Uninsured | 4 (4) |

| Household annual income, $ | |

| <30 000 | 43 (43) |

| 30 000-49 999 | 21 (21) |

| 50 000-99 999 | 18 (18) |

| ≥100 000 | 17 (17) |

| Not reported | 1 (1) |

| Education level | |

| ≤High school or general education diploma | 27 (27) |

| Some college or technical school | 47 (47) |

| 4-y College degree | 10 (10) |

| >4-y College degree | 16 (16) |

| Employment status | |

| Full time | 43 (43) |

| Part time | 5 (5) |

| Retired | 32 (32) |

| Disabled | 13 (13) |

| Unemployed | 7 (7) |

| Reside in rural countya | 23 (23) |

| Distance from University of Mississippi Medical Center, mean (SD), mi | 30.6 (30.2) |

| Digital consent obtained during work break | 10 (10) |

Defined by the US Office of Rural Health Policy.

Figure. County Residence and Annual Income of Study Participants.

Discussion

In this study using digital consent among individuals recruited from a broad population of individuals with hypertension, a substantial number of successfully enrolled participants were female, African American, and/or reporting a household income at or near the poverty level. Furthermore, more than 1 in 5 participants resided in a federally designated rural county. Electronic consent has been pioneered in smartphone app studies and internet-based clinical trials and represents a promising area to expand access and enhance medical research.3,4,5 However, many prior studies involving digital technology have included predominately white populations with higher socioeconomic status, raising concern for a growing digital divide among underserved populations.6 The present study adds to prior work by demonstrating the utility of digital consent and remote study enrollment to facilitate inclusion of populations underrepresented in clinical research.

The sample size enrolled is encouraging for our single-center study at an academic medical center; however, this consent strategy should be evaluated in other research environments to determine generalizability for other clinical trials. Additionally, further platform development is needed to optimize information exchange, participant understanding, and integration of digital consent into the larger research infrastructure. In conclusion, these findings support the use of digital technology to expand opportunities to participate in clinical research in underserved populations.

References

- 1.Kim SH, Tanner A, Friedman DB, Foster C, Bergeron CD. Barriers to clinical trial participation: a comparison of rural and urban communities in South Carolina. J Community Health. 2014;39(3):562-571. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9798-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grady C, Cummings SR, Rowbotham MC, McConnell MV, Ashley EA, Kang G. Informed consent. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):856-867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1603773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinhubl SR, Waalen J, Edwards AM, et al. Effect of a home-based wearable continuous ECG monitoring patch on detection of undiagnosed atrial fibrillation: the mSToPS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(2):146-155. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McConnell MV, Shcherbina A, Pavlovic A, et al. Feasibility of obtaining measures of lifestyle from a smartphone app: the MyHeart counts cardiovascular health study. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(1):67-76. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez AF, Fleurence RL, Rothman RL. The ADAPTABLE trial and PCORnet: shining light on a new research paradigm. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):635-636. doi: 10.7326/M15-1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huh J, Koola J, Contreras A, et al. Consumer health informatics adoption among underserved populations: thinking beyond the digital divide. Yearb Med Inform. 2018;27(1):146-155. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1641217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]