This randomized noninferiority clinical trial examines the effect of internet-delivered vs face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy especially in light of resources, access, and cost.

Key Points

Question

In the treatment of health anxiety, can internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy lead to comparable effects as conventional face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy while using less resources?

Findings

This randomized noninferiority clinical trial in a primary care setting included 204 adults with a principal diagnosis of health anxiety. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy was found to be noninferior to face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy while generating lower net societal costs.

Meaning

As internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy is not inferior to face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy and requires little resources, the online treatment format should be considered a first-line intervention for health anxiety.

Abstract

Importance

Health anxiety is a common and often chronic mental health problem associated with distress, substantial costs, and frequent attendance throughout the health care system. Face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is the criterion standard treatment, but access is limited.

Objective

To test the hypothesis that internet-delivered CBT, which requires relatively little resources, is noninferior to face-to-face CBT in the treatment of health anxiety.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized noninferiority clinical trial with health economic analysis was based at a primary care clinic and included patients with a principal diagnosis of health anxiety who were self-referred or referred from routine care. Recruitment began in December 10, 2014, and the last treatment ended on July 23, 2017. Follow-up data were collected up to 12 months after treatment. Analysis began October 2017 and ended March 2020.

Interventions

Patients were randomized (1:1) to 12 weeks of internet-delivered CBT or to individual face-to-face CBT.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Change in health anxiety symptoms from baseline to week 12. Analyses were conducted from intention-to-treat and per-protocol (completers only) perspectives, using the noninferiority margin of 2.25 points on the Health Anxiety Inventory, which has a theoretical range of 0 to 54.

Results

Overall, 204 patients (mean [SD] age, 39 [12] years; 143 women [70%]) contributed with 2386 data points on the Health Anxiety Inventory over the treatment period. Of 204 patients, 102 (50%) were randomized to internet-delivered CBT, and 102 (50%) were randomized to face-to-face CBT. The 1-sided 95% CI upper limits for the internet-delivered CBT vs face-to-face CBT difference in change were within the noninferiority margin in the intention-to-treat analysis (B = 0.00; upper limit: 1.98; Cohen d = 0.00; upper limit: 0.23) and per-protocol analysis (B = 0.01; upper limit: 2.17; Cohen d = 0.00; upper limit: 0.25). The between-group effect was not moderated by initial symptom level, recruitment path, or patient treatment preference. Therapists spent 10.0 minutes per patient per week in the online treatment vs 45.6 minutes for face-to-face CBT. The net societal cost was lower in the online treatment (treatment period point difference: $3854). There was no significant group difference in the number of adverse events, and no serious adverse event was reported.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this trial, internet-delivered CBT appeared to be noninferior to face-to-face CBT for health anxiety, while incurring lower net societal costs. The online treatment format has potential to increase access to evidence-based treatment for health anxiety.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02314065

Introduction

Health anxiety, also referred to as hypochondriasis, is a common, debilitating, and often chronic psychiatric condition1,2,3 characterized by an excessive and persistent fear or worry about serious illness. Throughout the health care system,4 health anxiety leads to excessive medical investigations and substantial societal costs.2 As medical reassurance does not lead to enduring improvement,5,6,7 health anxiety needs to be targeted by specific interventions.

Although there is some evidence in support of antidepressants in the treatment of health anxiety,8 the criterion standard treatment is cognitive behavior therapy (CBT).9 In CBT, the patient meets with a therapist, typically once a week over approximately 3 months. About 66% of patients respond to CBT,10 but given the prevalence of health anxiety and scarcity of mental health professionals, the need for treatment far exceeds the availability of evidence-based face-to-face therapy.

Internet-delivered CBT (ICBT) is a text-based online treatment in which the patient works with conventional CBT strategies and communicates regularly with a therapist through an email-like system.11 The patient can access the treatment at any time of the day, the treatment can be delivered regardless of geographical distances, and little time is required from the therapist. Thus, ICBT holds promise for increasing the outreach of psychological treatment.12

In the treatment of health anxiety, ICBT has been found to be more effective than a rudimentary attention control (d = 1.62; 95% CI, 1.10-2.10)13 and active comparator (pooled d = 0.81; 95% CI, −0.30 to 1.92)14,15 but has not yet been compared head to head with face-to-face CBT. Therefore, we conducted a randomized noninferiority clinical trial of the 2 treatment formats, within a primary care setting. Our primary hypothesis was that ICBT would be noninferior to individual face-to-face CBT, while requiring less therapist time and generating lower net societal costs.

Methods

Design

This was a randomized noninferiority clinical trial comparing ICBT to face-to-face CBT for health anxiety at a primary care clinic in Stockholm, Sweden. In Sweden, primary care clinics provide access to care for most common disease states, including anxiety disorders, and are intended to serve as first-line gatekeepers in authorizing access to specialty care. Adults with principal health anxiety were recruited through routine care referral and online self-referral. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1.

Participants

We informed local clinics about the study and advertised the study under the heading “Do you worry a lot about your health?” Recruitment began in December 10, 2014, and the last treatment ended on July 23, 2017. Applicants provided informed consent via the secure online platform and completed a comprehensive online screening battery. The study was approved by the Stockholm Regional Ethics Review Board (2014/1530-31/2). A face-to-face psychiatric interview was held with a clinical psychologist, as based on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview,16 the hypochondriasis module of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV,17 and the Health Preoccupation Diagnostic Interview.18 Based on the Health Preoccupation Diagnostic Interview, we included adults (≥18 years) with a principal diagnosis of DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder or illness anxiety disorder (these have replaced DSM-IV hypochondriasis and the diagnostic procedure has been found to be reliable18). Applicants who met criteria for a bipolar disorder or psychosis, severe depression (DSM-5 criteria), or recurrent clinically significant suicidal ideation (based on clinical judgement aided by a structured clinical interview and item 9 of the self-rated Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, rated from 0: “I have a normal appetite for life” to 6: “I am convinced that my only way out is to die, and I think a lot about how to best go about taking my own life”), a personality disorder likely to severely interfere with treatment, an alcohol or substance use disorder in the past 6 months, or a serious somatic condition that required immediate or extensive care, were excluded and referred to routine care. We required patients taking antidepressant medication to have been taking a stable dose for at least 2 months. Patients were also required not to have any other ongoing psychological treatments for health anxiety and not to have undergone CBT for health anxiety during the past year (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Randomization

Patients who met all eligibility criteria and completed the baseline assessment were randomly allocated (1:1) to ICBT or face-to-face CBT in consecutive even-numbered blocks. On each starting week, therapists were assigned an equal number of patients per treatment (ICBT vs face-to-face CBT) to balance therapist characteristics over the treatment arms. Randomization was based on a true random number service (http://www.random.org) and conducted by a member of the research group who was blinded to patient characteristics and otherwise not involved in the main phase of the trial. Because inclusion was a requirement for randomization, clinicians who conducted the eligibility interview could not anticipate treatment allocation.

Interventions

The ICBT and face-to-face CBT protocols were equivalent except for the delivery format (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Both treatments lasted 12 weeks and included standard cognitive behavioral techniques for health anxiety. Typically, the first 2 weeks focused on education about the CBT model of health anxiety, and subsequent weeks focused on exposure to health anxiety–provoking stimuli. Patients were encouraged to confront situations that trigger intrusions about illness and to refrain from behaviors believed to maintain health anxiety over time. For example, a patient with an excessive fear of having a weak heart, despite frequent medical reassurance, could be encouraged to exercise while refraining from pulse checking. The treatment also included mindfulness training as a means of increasing the patient’s willingness and ability to experience unwanted thoughts and emotions. To reduce dropout rates, we instructed therapists to telephone patients who canceled appointments or did not contact the therapist in the online platform. The therapists did not use these telephone calls to convey treatment content.

Therapist-Guided ICBT

In ICBT, patients gained access to their treatment through a secure website. Here, patients could communicate freely with their therapist by way of an email-like system and expect a reply within 48 hours on weekdays. The treatment was communicated via a self-help text divided into 12 chapters (ie, modules). We encouraged patients in ICBT to complete about 1 module per week, and patients received feedback from the therapist after each module (eAppendix 1 and eFigures 1-3 in Supplement 2).

Individual Face-to-Face CBT

Patients randomized to face-to-face CBT were expected to attend 12 weekly in-person sessions with their therapist and to work with daily homework assignments. The treatment followed a written manual, and exposure and response prevention was tailored to suit the needs of each patient. The first session lasted 80 minutes and the remaining were approximately 50 minutes (eAppendix 2 in Supplement 2).

Therapists

Therapists in ICBT and face-to-face CBT were the same 5 psychologists (3 of which were authors: E. Axelsson, D.B., and M. H.-L.), employed at the primary care clinic. All therapists were psychologists with training in CBT (eTable 3 in Supplement 2) who were introduced to the study by one of the authors (E. Axelsson) and given scheduled reading time, detailed manuals with case studies, session-by-session adherence checklists, examples of email correspondence in ICBT, and an audio recording of a competently delivered CBT session. Every other week, therapists attended 40 to 60 minutes of supervision with 1 of 2 authors (E. Axelsson or E. H.-L.). At the beginning of the trial, 3 of 5 therapists preferred noninferiority as the outcome of the trial, and 3 of 5 expected this outcome (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Assessment of Treatment Fidelity

In accordance with research recommendations,19 audio from all face-to-face CBT sessions were recorded and a random 10% (109 of 1059) of these files, stratified by period and therapist, were anonymized and assessed for fidelity by trained clinicians (eAppendix 5 in Supplement 2). Ratings were primarily based on a structured 27-item instrument developed to capture key aspects of therapist adherence from 0% (very poor) to 100% (excellent) and competence from 0 (very poor) to 5 (excellent). An initial concordance check based on 4 recordings indicated excellent interrater reliability (adherence: perfect agreement; competence: intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.77).

Outcomes

Primary outcome was change (slope) in health anxiety over the treatment period, as measured using the clinical reference standard 18-item Health Anxiety Inventory (HAI), which has a theoretical range of 0 to 54.20 For the primary analysis, patients completed the HAI at baseline, each week during treatment, and at posttreatment. Follow-up assessments were also conducted 6 and 12 months after treatment completion. The HAI has excellent psychometric properties21 and is widely used. In this study, response was operationalized as an HAI score reduction more than 7.74 points, remission as an end point score below 23.55 points, and clinically significant improvement was the combination of response and remission (eAppendix 7 in Supplement 2).22

Secondary self-rated outcome questionnaires were completed online at baseline, immediately after treatment, and 6 and 12 months after treatment (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). We measured general anxiety using the Beck Anxiety Inventory,23 depression using the self-rated Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale24 and disability using the Sheehan Disability Scale.25 We also measured health anxiety using the Illness Attitude Scales26 and Whiteley Index,27 anxiety sensitivity using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index,28 sleep disturbance using the Insomnia Severity Index,29 alcohol use using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test,30 and disability using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.31 At week 2, treatment credibility was assessed using the C scale32 and therapeutic alliance using the Working Alliance Inventory.33 Adverse events and treatment satisfaction34 were assessed at posttreatment. Data on resource utilization in the preceding month35 (used to estimate costs) and health-related quality of life36 were collected at baseline, posttreatment, and at follow-up (eAppendix 8 in Supplement 2). At posttreatment and follow-up, we also asked about parallel treatments.

Statistical Analysis and Power Calculation

The primary noninferiority and power analyses were done by an independent statistician, and the analysis plan for the primary outcome was finalized in August 2016. Analysis began October 2017. Change over time was modeled using mixed-effects linear regression (patients at level 2) with a random intercept and slope (time). That is, the HAI was regressed on time (baseline to end point), group (ICBT vs face-to-face treatment), and the time × group interaction. We considered ICBT to be noninferior to face-to-face CBT if the upper bound of the 1-sided confidence interval for the time × group interaction (α = .05) was within the a priori noninferiority margin of 2.25 points on the HAI (Cohen d of approximately 0.3). We decided on this noninferiority margin based on expert consensus, the confidence interval for the effect of CBT vs nonactive controls,37 and what most clinicians and patients consider a minimally important difference on patient-reported outcomes.38 Monte Carlo simulations indicated that a sample size of 200 would be required for 80% power to confirm noninferiority in the primary analysis (Supplement 1). As the intention-to-treat approach may indicate noninferiority simply due to poor adherence to the study protocol, in a sensitivity analysis, we also investigated noninferiority within a per-protocol framework with data from patients who had initiated at least 6 modules in ICBT, or attended at least 6 sessions in face-to-face CBT. We also estimated Cohen d by dividing the time × group coefficient by the pooled observed end point standard deviation. The main outcome of this trial was reported in a doctoral dissertation in 2018.39

We based all secondary analyses on 2-sided tests and the α level of 5%. In moderator analyses, we tested if the primary outcome was moderated by treatment preference (0 indicates strong preference for face-to-face CBT and 5, strong preference for ICBT), path of recruitment (routine care vs not routine care), and baseline health anxiety. As this trial lacked a nonactive control group, we also tested for dose-response relationships, ie, the effect of the number of sessions or modules on the slope of the HAI. For all secondary analyses of change, data were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations (20 samples). In the analysis of long-term outcomes, piecewise linear mixed models were fitted with a spline at the posttreatment assessment. Furthermore, we explored dichotomous outcomes in terms of response, remission, and clinically significant improvement. In health economic analyses, we compared ICBT to face-to-face CBT with regard to societal costs in relation to clinical efficacy (cost effectiveness) and quality-adjusted life-years (cost utility). Costs included costs of therapies and medications (including the cost of ICBT or face-to-face CBT), costs of nonmedical help and services, and indirect costs such as those of unemployment (eAppendix 3 and 4 in Supplement 2).

Results

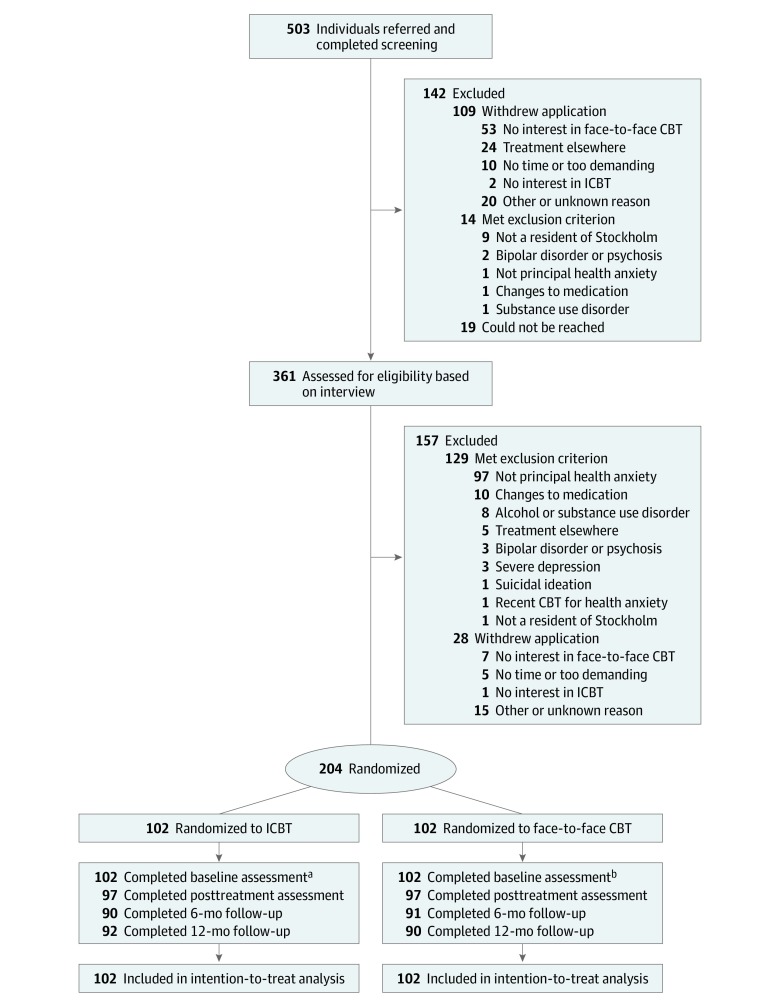

Between December 2014 and March 2017, 503 applicants completed the online screening battery, and 159 (32%) of these were referred from routine care (Figure 1). In total, 204 patients were included and randomized to either ICBT (102 [50%]) or face-to-face CBT (102 [50%]). We collected 2386 data points on the HAI during the treatment phase (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were evenly distributed between the treatment groups (Table 1). The mean (SD) age was 39 (12) years. Most patients were women (143 [70%]), married (168 [82%]), had a postsecondary or university education (154 [75%]), were currently employed (137 [67%]), and had experienced health anxiety for 9 years but never received psychological treatment (171 [84%]). Forty-six patients reported having a somatic condition out of the ordinary (eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Most commonly, this was hypothyroidism (n = 12), followed by hypertension (n = 8), irritable bowel syndrome (n = 5), and osteoarthritis (n = 4).

Figure 1. Flow of Recruitment to Internet-Delivered and Face-to-Face Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT).

Study participants were randomized to either individual face-to-face CBT or therapist-guided internet-delivered CBT (ICBT).

aA total of 101, 96, 94, 90, 90, 90, 89, 88, 87, 84, and 83 individuals completed assessments at week 1 to 11, respectively.

bA total of 95, 97, 90, 94, 93, 89, 87, 85, 88, 89 and 89 individuals completed assessments at week 1 to 11, respectively.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics at Baseline.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICBT (n = 102) | FTF-CBT (n = 102) | Total (N = 204) | |

| Sociodemographic variables | |||

| Age, mean (SD) [range], y | 39 (12) [19-65] | 39 (13) [18-78] | 39 (12) [18-78] |

| Female | 72 (71) | 71 (70) | 143 (70) |

| Educational level | |||

| Upper secondary schoola or lower | 26 (25) | 24 (24) | 50 (25) |

| Postsecondary or universityb | 76 (75) | 78 (76) | 154 (75) |

| Married or de facto marriage | 82 (80) | 86 (84) | 168 (82) |

| Employment | |||

| Working | 72 (71) | 65 (64) | 137 (67) |

| Student | 12 (12) | 10 (10) | 22 (11) |

| Unemployed | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 7 (3) |

| Sick leave or disability pension | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 5 (2) |

| Otherc | 13 (13) | 20 (20) | 33 (16) |

| Clinical variables | |||

| Health anxiety core characteristics | |||

| Health anxiety (HAI), mean (SD) | 33.9 (6.5) | 34.2 (6.4) | 34.0 (6.4) |

| DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder | 58 (57) | 58 (57) | 116 (57) |

| DSM-5 illness anxiety disorder | 46 (45) | 44 (43) | 90 (44) |

| DSM-IV hypochondriasis | 98 (96) | 93 (91) | 191 (94) |

| Age of onset, y, mean (SD) | 27 (12) | 27 (14) | 27 (13) |

| Total duration, y, mean (SD) | 9.3 (10.4) | 9.1 (8.5) | 9.2 (9.4) |

| Therapy-naive (psychological) | 85 (83) | 86 (84) | 171 (84) |

| Secondary psychiatric characteristics | |||

| At least 1 other anxiety disorder or OCD | 67 (66) | 59 (58) | 126 (62) |

| Major depressive disorder | 23 (23) | 21 (21) | 44 (22) |

| General anxiety (BAI), mean (SD) | 19.4 (8.9) | 20.3 (10.5) | 19.8 (9.7) |

| Depression (MADRS-S), mean (SD) | 13.8 (6.9) | 14.7 (7.0) | 14.2 (7.0) |

| Disability (SDS), mean (SD) | 11.4 (7.5) | 11.6 (6.8) | 11.5 (7.1) |

| Self-reported somatic conditiond | 22 (22) | 24 (24) | 46 (23) |

| Path of referral | |||

| Routine care | 39 (38) | 28 (27) | 67 (33) |

| Not routine care | 63 (62) | 74 (73) | 137 (67) |

| Patient’s treatment preferencee | |||

| Mild or clear preference for ICBT | 38 (37) | 36 (35) | 74 (36) |

| No preference | 16 (16) | 22 (22) | 38 (19) |

| Mild or clear preference for CBT | 48 (47) | 44 (43) | 92 (45) |

Abbreviations: BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; FTF-CBT, individual face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy; HAI, 18-item Health Anxiety Inventory; ICBT, internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy; MADRS-S, self-rated Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale.

Swedish gymnasium, equivalent to international standard classification of education level 3.

Postsecondary or university, international standard classification of education level 4 or higher.

Domestic work only, parental leave, or retired.

This refers to an item in the clinical interview in which a clinical psychologist asked patients whether they had a somatic disease out of the ordinary.

These variables were generated from responses to an interview question that had 5 response options on a scale from strong preference for conventional CBT to strong preference for ICBT, with a neutral middle option phrased “no preference.”

Primary Outcome

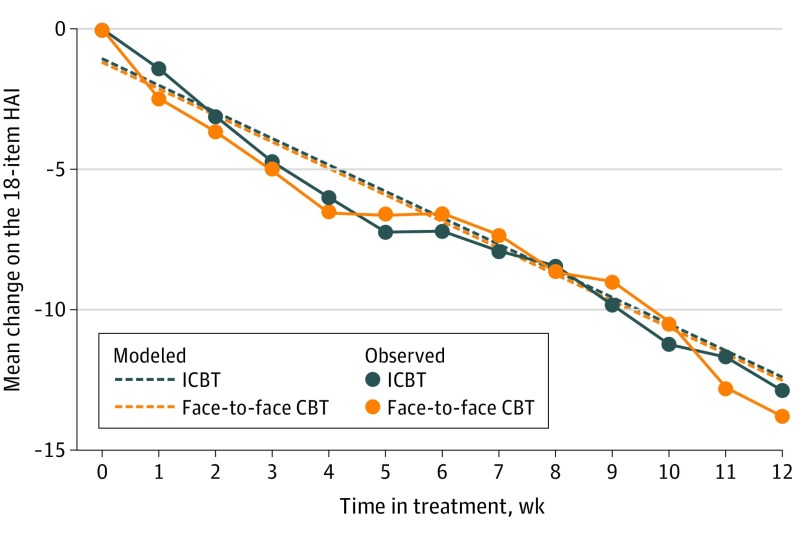

In the intention-to-treat analysis, the estimated difference in effect over the treatment period was 0.00 points on the primary outcome (HAI), and the upper limit of the 1-sided 95% CI was 1.98. The per-protocol analysis was indicative of a difference of 0.01 points in favor of individual face-to-face CBT, with the upper limit of the 95% CI being 2.17. Thus, both models converged with confidence interval upper bounds within the noninferiority margin of 2.25, indicating that ICBT was noninferior to individual face-to-face CBT (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Observed and Modeled Mean Change in Health Anxiety by Treatment Group.

Estimated values are based on the fixed portion of mixed-effects linear regression models and intention-to-treat data (ie, all patients in the study were included). Error bars are omitted for clarity of presentation. Study participants were randomized to either individual face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) or therapist-guided internet-delivered CBT (ICBT). HAI indicates Health Anxiety Inventory.20

Putative Moderators and Dose-Response Relationship

The main outcome was not significantly moderated by the patient’s baseline treatment preference (B = −1.28; 95% CI, −2.90 to 0.34), health anxiety (HAI; B = 0.23; 95% CI, −0.15 to 0.62), or whether the patient was referred from routine care (B = 2.33; 95% CI, −2.63 to 7.30). Recruitment path was also not a significant predictor of preference. Significantly larger reductions in health anxiety were seen for patients who completed more modules in ICBT (B = −0.44; 95% CI, −0.88 to −0.01) or attended more sessions in face-to-face CBT (B = −0.92; 95% CI, −1.57 to −0.26).

Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

At the primary end point, responder rates did not differ significantly between the treatments: 78 of 102 (76%) in ICBT vs 75 of 102 (74%) in face-to-face CBT (eTables 9-14 in Supplement 2). No treatment had significantly higher effects on secondary symptom outcomes at the primary end point (Table 2; eTables 7 and 8 and eAppendix 6 in Supplement 2). Within-group effects on health anxiety were large for both ICBT (d = 1.76) and face-to-face CBT (d = 1.76) with sustained effects at follow-up.

Table 2. Change in Symptoms From Baselinea.

| Characteristic | Change from baseline | Difference: ICBT to FTF-CBT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed, B | Random | ||||||

| ICBT | FTF-CBT | Baseline to posttreatment, SD | Posttreatment to 12 mo, SD | r | Unstandardized, B (95% CI) | Standardized, d (95% CI)b | |

| Health anxiety (HAI) | |||||||

| Posttreatmentc | −11.3 | −11.3 | 7.8 | NA | NA | 0.0 (2.0)d | 0.00 (0.23)d |

| 6 mo | −11.9 | −13.0 | 7.8 | 7.9 | −0.48 | 1.1 (−1.1 to 3.2) | 0.12 (−0.13 to 0.37) |

| 12 mo | −12.4 | −14.7 | 7.8 | 7.9 | −0.48 | 2.4 (−0.4 to 5.1) | 0.26 (−0.05 to 0.58) |

| General anxiety (BAI) | |||||||

| Posttreatment | −7.6 | −9.0 | 7.6 | 5.9 | −0.21 | 1.4 (−1.5 to 4.2) | 0.17 (−0.18 to 0.52) |

| 6 mo | −7.0 | −9.6 | 7.6 | 5.9 | −0.21 | 2.5 (−0.1 to 5.2) | 0.30 (−0.02 to 0.61) |

| 12 mo | −6.5 | −10.2 | 7.6 | 5.9 | −0.21 | 3.7 (0.5 to 6.8) | 0.45 (0.07 to 0.83) |

| Depression (MADRS-S) | |||||||

| Posttreatment | −5.3 | −7.0 | 5.4 | 3.7 | −0.05 | 1.7 (−0.4 to 3.7) | 0.26 (−0.07 to 0.59) |

| 6 mo | −5.5 | −7.8 | 5.4 | 3.7 | −0.05 | 2.3 (0.4 to 4.3) | 0.39 (0.06 to 0.71) |

| 12 mo | −5.7 | −8.7 | 5.4 | 3.7 | −0.05 | 3.0 (0.6 to 5.4) | 0.53 (0.11 to 0.95) |

| Functional impairment (SDS) | |||||||

| Posttreatment | −4.4 | −5.4 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.13 | 1.0 (−0.9 to 2.9) | 0.17 (−0.15 to 0.49) |

| 6 mo | −5.1 | −6.2 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.13 | 1.1 (−0.7 to 2.9) | 0.18 (−0.12 to 0.47) |

| 12 mo | −5.7 | −6.9 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.13 | 1.2 (−1.2 to 3.6) | 0.20 (−0.20 to 0.61) |

Abbreviations: BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; FTF-CBT, individual face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy; HAI, 18-item Health Anxiety Inventory; ICBT, internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy; MADRS-S, self-rated Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; NA, not applicable; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale.

Intention-to-treat estimates based on piecewise linear mixed-effects models with a spline at the posttreatment assessment, fitted on data with missing values imputed separately for each treatment group using multiple imputation by chained equations. Differences represent the coefficient for the time × group interaction.

Cohen d effect sizes calculated as the model-implied mean difference divided by the pooled observed end point standard deviation.

This was the model used for the primary analysis test of noninferiority. Unlike the secondary outcomes, the HAI was administered on a weekly basis over the course of the treatment. As the repeated measurements design allowed for a model that was robust to missing data points, this model was not fitted on multiply-imputed data.

This confidence interval is 1-sided in accordance with the power analysis and data analysis plan.

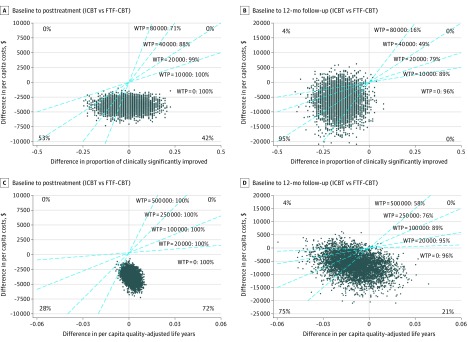

Health Economic Outcomes

The main outcomes of the health economic evaluation are presented in Figure 3. Evidently, it is highly probable that ICBT incurs lower net societal costs than face-to-face CBT, mainly owing to lower therapist costs (mean [SD]: $454 [257] vs $2059 [595]) (eTables 15, 16, and 17 in Supplement 2). As can be seen in Figure 3A, from baseline to the primary end point, ICBT was associated with a similar rate of clinically significant improvement as face-to-face CBT but at a lower net societal cost. eTable 18, eAppendices 8-11, and eFigure 4 in Supplement 2 include a comprehensive presentation of the health economic evaluation.

Figure 3. Cost-Effectiveness and Cost-Utility of Therapist-Guided Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavior Therapy (ICBT) vs Individual Face-to-Face Cognitive Behavior Therapy (FTF-CBT) for Health Anxiety.

Cost-effectiveness analysis (A and B) and cost-utility analysis (C and D). In each of the 4 panels (A, B, C, and D), the cost-effectiveness plane has 4 quadrants. Points in the first (northeast) quadrant are indicative of higher ICBT (vs FTF-CBT) net costs and higher ICBT (vs FTF-CBT) efficacy, points in the second (northwest) quadrant are indicative of higher ICBT (vs FTF-CBT) net costs and lower ICBT (vs FTF-CBT) efficacy, points in the third (southwest) quadrant are indicative of lower ICBT (vs FTF-CBT) net costs and lower ICBT (vs FTF-CBT) efficacy, and points in the fourth (southeast) quadrant are indicative of lower ICBT (vs FTF-CBT) net costs and higher ICBT (vs FTF-CBT) efficacy. Each blue line has a coefficient corresponding to a hypothetical level of societal willingness-to-pay (WTP) per unit of efficacy, ie, additional responder or quality-adjusted life-year. The proportion of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios right of a blue line indicate the probability of ICBT being more cost-effective than FTF-CBT at the corresponding WTP.

Treatment Fidelity and Integrity of the Protocol

Face-to-face therapist adherence (mean [SD] percentage score, 98 [0.1]) and competence (mean [SD], 4.5 [0.6]) were good to excellent, indicating high treatment fidelity. Therapists spent a mean (SD) of 10.0 (5.7) minutes per patient per week in ICBT and 45.6 (13.1) minutes in face-to-face CBT. There was a smaller proportion of treatment completers in ICBT than in face-to-face CBT (81 of 102 [79.4%] vs 92 of 102 [90.2%]). The median (interquartile range) number of initiated ICBT modules was 11 (6-12), and the median (interquartile range) number of attended face-to-face CBT sessions was 12 (11-12).

There was no significant difference between patients in ICBT and face-to-face CBT with regard to changes in psychotropic medication over the treatment period (6 of 97 [6.2%] vs 5 of 97 [5.1%]) or the follow-up period (7 of 92 [7.6%] vs 10 of 89 [11.2%]), or other psychological treatments during the treatment period (3 of 97 (3.1%) vs 0 of 97 [0%]) or follow-up period (10 of 92 [10.9%] vs 8 of 89 [9.0%]). Therapeutic alliance was rated significantly lower in ICBT than in face-to-face CBT (mean [SD], 32.3 [7.9] vs 36.3 [5.9]), but there was no significant difference in treatment credibility (mean [SD], 35.3 [8.4] vs 37.5 [6.6]; 95% CI 0.0-4.2; P = .05).

Adverse Events

At least 1 adverse event was reported by 19 of 97 patients in ICBT (20%) and 17 of 97 patients in face-to-face CBT (18%). This difference was not significant. The most commonly reported type of adverse event in both treatments was increased anxiety or stress (16 [16%] vs 14 [14%]). No serious adverse events were reported (eAppendix 12 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

Results from this large-scale noninferiority trial conducted in a primary care setting showed that ICBT, while incurring lower net societal costs, was not inferior to individual face-to-face CBT for patients with health anxiety. The robustness of this conclusion was indicated by intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses converging on the same outcome. Compared with face-to-face CBT, ICBT therapists spent 78% less time per patient. Yet, both treatments achieved large effects on health anxiety and moderate to large effects on general anxiety and depression.

To our knowledge, this is the first noninferiority trial to compare ICBT with criterion standard face-to-face CBT for health anxiety. It is also, to our knowledge, the largest randomized controlled comparison between ICBT and face-to-face therapy for any mental health condition.40 Four previous randomized clinical trials also corroborate that ICBT has beneficial effects on health anxiety.13,14,15,41 We have found ICBT to have specific effects beyond those of an active, structured, and credible treatment in the form of internet-delivered behavioral stress management.14 Another research group has also found ICBT to be more efficacious than the fortnightly provision of psychoeducational material.15

Health anxiety is prevalent, not least in medical clinics,4 tends to persist over time without treatment,3 and is associated with increased health care consumption.2 ICBT reduces the time needed per treatment, does not require patients to work with their treatment during any particular time of the day, and allows clinics to have a nationwide outreach. Tentatively, there is typically no need for clinicians to select specific patients for ICBT. That being said, just like certain patients are not able to participate in face-to-face CBT for example owing to geographical barriers, others are not able to participate fully in text-based ICBT for example owing to difficulties reading and writing. It should also be mentioned that exploratory analyses pointed to face-to-face CBT being associated with slightly higher adherence and moderately larger effects on general anxiety and depression in the long term. At 12 months, the between-group effect on health anxiety (2.4 points on the HAI) was clinically but not statistically significant. In summary, although differences appear to be rather small also in the long term, they could be clinically meaningful, and more data are needed to draw firm conclusions in this regard.

Strengths and Limitations

Quality markers of this trial were a well-powered sample, minimal data loss, the predetermined primary statistical model, the high degree of treatment fidelity and therapist competence, and also that treatment content and therapist assignment were balanced over the treatment groups. The within-group effects of face-to-face CBT were large and similar to those seen in previous studies, indicating that the comparison group in this trial was valid.

This trial also had limitations. First, the sample had a relatively high mean level of education, which may affect the generalizability of our findings. However, baseline health anxiety was high and most patients had been ill for years. Second, there were no posttreatment psychiatric interviews. Still, we believe that the choice of the HAI as primary outcome was ideal because health anxiety is a dimensional phenomenon and there appears to exist no clear boundary between moderate and severe worry about health.42 The HAI has also been used as primary outcome in previous randomized clinical trials15,43 and is a valid instrument21 that enabled a repeated measurements design with high statistical power. Third, we did not ask our patients about all specific putative parallel treatments, eg, interval treatment, throughout the study. However, we did establish that the treatment groups did not differ with regard to psychotropic medication or parallel psychological interventions. Also, based on free text questions that prompted patients to report all health care visits and medical expenses, medical costs were comparable in the 2 groups (eTable 15 in Supplement 2). Fourth, although we followed up patients up to 12 months after treatment, this trial was not powered to assess noninferiority over the follow-up period. However, at least in the short term, it seems that when face-to-face CBT works, ICBT is a noninferior intervention with potential to markedly increase the availability of efficacious treatment for individuals with health anxiety.

Conclusions

Based on the findings of this trial and previous evidence, we conclude that therapist-guided ICBT is noninferior to individual face-to-face CBT for patients with health anxiety. Given the low societal costs of ICBT for health anxiety, our findings highlight the potential benefits of implementing this treatment on a wider scale.

Trial Protocol.

eTable 1. Operationalization of Eligibility Criteria

eTable 2. Treatment Protocol, Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Health Anxiety

eTable 3. Detailed Description of Therapists

eTable 4. Properties of Key Outcome Measures

eTable 5. Weekly Data Completion Rates, Primary Outcome (2386 Data Points)

eTable 6. Somatic Conditions Reported at Baseline

eTable 7. Observed Means and Standard Deviations

eTable 8. Change in Additional Secondary Outcomes From Baseline

eTable 9. Response Rates, Total Sample

eTable 10. Response Rates, Per Protocol

eTable 11. Remission Rates, Total Sample

eTable 12. Remission Rates, Per Protocol

eTable 13. Clinically Significant Improvement, Total Sample

eTable 14. Clinically Significant Improvement, Per Protocol

eTable 15. Crude (Observed) Monthly Costs at Baseline and Post-Treatment

eTable 16. Crude (Observed) Monthly Costs at the 6- and 12-Month Follow-Up

eTable 17. Intervention Costs by Treatment Group

eTable 18. Modelled Net Total Costs Per Observation Period

eFigure 1. Online Treatment Platform, Text-Based Main View

eFigure 2. Online Treatment Platform, Interactive Work Sheet

eFigure 3. Online Treatment Platform, Homework Report

eFigure 4. Cost-Effectiveness and Cost-Utility, Alternative Calculation of Costs

eAppendix 1. Detailed Description of Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavior Therapy

eAppendix 2. Detailed Description of Face-to-Face Cognitive Behavior Therapy

eAppendix 3. Statistical Analysis (continued)

eAppendix 4. Aug 2016 Revision of Primary Analysis

eAppendix 5. Treatment Fidelity: Sensitivity Analysis and the Online Treatment

eAppendix 6. Satisfaction With Treatment

eAppendix 7. Criteria for Response, Remission, and Clinically Significant Improvement

eAppendix 8. Measurement of Resource Utilization and Health-Related Quality of Life

eAppendix 9. Health Economic Analysis

eAppendix 10. Health Economic Point Estimates

eAppendix 11. Health Economy Sensitivity Analysis: Alternative Calculation of Costs

eAppendix 12. Measurement of Adverse Events

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Barsky AJ. Clinical practice: the patient with hypochondriasis. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1395-1399. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp002896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sunderland M, Newby JM, Andrews G. Health anxiety in Australia: prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service use. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(1):56-61. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.olde Hartman TC, Borghuis MS, Lucassen PL, van de Laar FA, Speckens AE, van Weel C. Medically unexplained symptoms, somatisation disorder and hypochondriasis: course and prognosis: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(5):363-377. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyrer P, Cooper S, Crawford M, et al. Prevalence of health anxiety problems in medical clinics. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(6):392-394. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucock MP, Morley S, White C, Peake MD. Responses of consecutive patients to reassurance after gastroscopy: results of self administered questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1997;315(7108):572-575. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7108.572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, Morley S, Selby P, House A. Reassurance and the anxious cancer patient. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(5):893-899. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasteiger C, Sherriff R, Fraser A, Shedden-Mora MC, Petrie KJ, Serlachius AS. Predicting patient reassurance after colonoscopy: the role of illness beliefs. J Psychosom Res. 2018;114:58-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallon BA, Ahern DK, Pavlicova M, Slavov I, Skritskya N, Barsky AJ. A randomized controlled trial of medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy for hypochondriasis. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16020189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barsky AJ, Ahern DK. Cognitive behavior therapy for hypochondriasis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(12):1464-1470. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.12.1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Axelsson E, Hedman-Lagerlöf E. Cognitive behavior therapy for health anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical efficacy and health economic outcomes. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(6):663-676. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2019.1703182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedman E. Therapist guided internet delivered cognitive behavioural therapy. BMJ. 2014;348:g1977. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes EA, Ghaderi A, Harmer CJ, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on psychological treatments research in tomorrow’s science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(3):237-286. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30513-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedman E, Andersson G, Andersson E, et al. Internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for severe health anxiety: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(3):230-236. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.086843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedman E, Axelsson E, Görling A, et al. Internet-delivered exposure-based cognitive-behavioural therapy and behavioural stress management for severe health anxiety: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(4):307-314. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.140913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newby JM, Smith J, Uppal S, Mason E, Mahoney AEJ, Andrews G. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy versus psychoeducation control for illness anxiety disorder and somatic symptom disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86(1):89-98. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiNardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Client interview schedule. Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Axelsson E, Andersson E, Ljótsson B, Wallhed Finn D, Hedman E. The health preoccupation diagnostic interview: inter-rater reliability of a structured interview for diagnostic assessment of DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2016;45(4):259-269. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2016.1161663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perepletchikova F, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity and therapeutic change: issues and research recommendations. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2006;12(4):365-383. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpi045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick HM, Clark DM. The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32(5):843-853. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702005822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alberts NM, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Jones SL, Sharpe D. The Short Health Anxiety Inventory: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(1):68-78. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(1):12-19. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893-897. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Svanborg P, Åsberg M. A new self-rating scale for depression and anxiety states based on the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89(1):21-28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27(2):93-105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kellner R. Appendix A: illness attitude scales In: Somatization and Hypochondriasis. Praeger Publishers; 1986:319-324. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pilowsky I. Dimensions of hypochondriasis. Br J Psychiatry. 1967;113(494):89-93. doi: 10.1192/bjp.113.494.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24(1):1-8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297-307. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791-804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ustün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, et al. ; WHO/NIH Joint Project . Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(11):815-823. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.067231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;3(4):257-260. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(72)90045-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatcher RL, Gillaspy JA. Development and validation of a revised short version of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychother Res. 2006;16(1):12-25. doi: 10.1080/10503300500352500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann. 1982;5(3):233-237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Van Straten A, Donker M, Tiemens B. Trimbos/iMTA Questionnaire for Costs Associated With Psychiatric Illness (TIC-P). Institute for Medical Technology Assessment, Erasmus University Rotterdam; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.EuroQol Group EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199-208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olatunji BO, Kauffman BY, Meltzer S, Davis ML, Smits JA, Powers MB. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for hypochondriasis/health anxiety: a meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. Behav Res Ther. 2014;58:65-74. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(2):102-109. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Axelsson E. Severe Health Anxiety: Novel approaches to Diagnosis and Psychological Treatment. Dept of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlbring P, Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Riper H, Hedman-Lagerlöf E. Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2018;47(1):1-18. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2017.1401115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hedman E, Axelsson E, Andersson E, Lekander M, Ljótsson B. Exposure-based cognitive-behavioural therapy via the internet and as bibliotherapy for somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(5):407-413. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.181396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asmundson GJR, Taylor S, Carleton RN, Weeks JW, Hadjstavropoulos HD. Should health anxiety be carved at the joint? a look at the health anxiety construct using factor mixture modeling in a non-clinical sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26(1):246-251. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tyrer P, Cooper S, Salkovskis P, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for health anxiety in medical patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):219-225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61905-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eTable 1. Operationalization of Eligibility Criteria

eTable 2. Treatment Protocol, Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Health Anxiety

eTable 3. Detailed Description of Therapists

eTable 4. Properties of Key Outcome Measures

eTable 5. Weekly Data Completion Rates, Primary Outcome (2386 Data Points)

eTable 6. Somatic Conditions Reported at Baseline

eTable 7. Observed Means and Standard Deviations

eTable 8. Change in Additional Secondary Outcomes From Baseline

eTable 9. Response Rates, Total Sample

eTable 10. Response Rates, Per Protocol

eTable 11. Remission Rates, Total Sample

eTable 12. Remission Rates, Per Protocol

eTable 13. Clinically Significant Improvement, Total Sample

eTable 14. Clinically Significant Improvement, Per Protocol

eTable 15. Crude (Observed) Monthly Costs at Baseline and Post-Treatment

eTable 16. Crude (Observed) Monthly Costs at the 6- and 12-Month Follow-Up

eTable 17. Intervention Costs by Treatment Group

eTable 18. Modelled Net Total Costs Per Observation Period

eFigure 1. Online Treatment Platform, Text-Based Main View

eFigure 2. Online Treatment Platform, Interactive Work Sheet

eFigure 3. Online Treatment Platform, Homework Report

eFigure 4. Cost-Effectiveness and Cost-Utility, Alternative Calculation of Costs

eAppendix 1. Detailed Description of Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavior Therapy

eAppendix 2. Detailed Description of Face-to-Face Cognitive Behavior Therapy

eAppendix 3. Statistical Analysis (continued)

eAppendix 4. Aug 2016 Revision of Primary Analysis

eAppendix 5. Treatment Fidelity: Sensitivity Analysis and the Online Treatment

eAppendix 6. Satisfaction With Treatment

eAppendix 7. Criteria for Response, Remission, and Clinically Significant Improvement

eAppendix 8. Measurement of Resource Utilization and Health-Related Quality of Life

eAppendix 9. Health Economic Analysis

eAppendix 10. Health Economic Point Estimates

eAppendix 11. Health Economy Sensitivity Analysis: Alternative Calculation of Costs

eAppendix 12. Measurement of Adverse Events

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement