Key Points

Question

Is interval resection after successful inpatient nonoperative management of complicated diverticulitis associated with the rate of disease-specific emergency surgery or death in 2 contrasting health care systems?

Findings

In this secondary cohort analysis, 3280 of 13 861 patients (24%) in Switzerland and 231 of 5129 patients (5%) in Scotland with complicated diverticulitis managed nonoperatively underwent an interval colon resection. Despite this 5-fold difference, the rate of emergency surgery or death was 5% in both countries.

Meaning

High rates of interval resection were not associated with reduced rates of emergency surgery or death after nonoperatively managed complicated diverticulitis.

Abstract

Importance

National guidelines on interval resection for prevention of recurrence after complicated diverticulitis are inconsistent. Although US and German guidelines favor interval colonic resection to prevent a perceived high risk of recurrence, UK guidelines do not.

Objectives

To investigate patient management and outcomes after an index inpatient episode of nonoperatively managed complicated diverticulitis in Switzerland and Scotland and determine whether interval resection was associated with the rate of disease-specific emergency surgery or death in either country.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This secondary analysis of anonymized complete national inpatient data sets included all patients with an inpatient episode of successfully nonoperatively managed complicated diverticulitis in Switzerland and Scotland from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2015. The 2 countries have contrasting health care systems: Switzerland is insurance funded, while Scotland is state funded. Statistical analysis was conducted from February 1, 2018, to October 17, 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point defined a priori before the analysis was adverse outcome, defined as any disease-specific emergency surgical intervention or inpatient death after the initial successful nonsurgical inpatient management of an episode of complicated diverticulitis, including complications from interval elective surgery.

Results

The study cohort comprised 13 861 inpatients in Switzerland (6967 women) and 5129 inpatients in Scotland (2804 women) with an index episode of complicated acute diverticulitis managed nonoperatively. The primary end point was observed in 698 Swiss patients (5.0%) and 255 Scottish patients (5.0%) (odds ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.81-1.19). Elective interval colonic resection was undertaken in 3280 Swiss patients (23.7%; median follow-up, 53 months [interquartile range, 24-90 months]) and 231 Scottish patients (4.5%; median follow-up, 57 months [interquartile range, 27-91 months]). Death after urgent readmission for recurrent diverticulitis occurred in 104 patients (0.8%) in Switzerland and 65 patients (1.3%) in Scotland. None of the investigated confounders had a significant association with the outcome apart from comorbidity.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found no difference in the rate of adverse outcome (emergency surgery and/or inpatient death) despite a 5-fold difference in interval resection rates.

This study investigates patient management and outcomes after an index inpatient episode of nonoperatively managed complicated diverticulitis in Switzerland and Scotland and examines whether interval resection was associated with the rate of disease-specific emergency surgery or death.

Introduction

Diverticulitis accounts for more than 200 000 inpatient admissions per year in the United States. Most cases are mild (uncomplicated), but 10% to 15% of patients present with complicated diverticulitis, defined as the presence of intra-abdominal abscess, fistula, free perforation, or hemorrhage. Up to 50% of this group requires emergency surgery at the index admission, which has a high mortality rate.1,2,3 Acute recurrent diverticulitis is more likely after complicated diverticulitis and occurs in up to 70% of cases depending on disease severity and host factors (eg, immunosuppression or collagen or vascular disease).4,5 One objective of elective resection is to prevent emergency re-presentation with life-threatening abdominal sepsis from recurrent complicated diverticulitis. However, societal guidelines for the management of patients after a first episode of complicated diverticulitis managed nonoperatively are inconsistent. Although the practice parameters of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons6 and the German S2k (Code of the German Clinical Practice Guideline Working Group) guidelines7 support elective resections for all patients after successful nonoperative management of complicated diverticulitis, the guidelines of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland8 conclude that only select patients should be considered for elective surgery on the basis of the same evidence.6,7,8,9 These differing recommendations may be associated with contrasting models of health care in the UK compared with Western Europe and North America, notably that there is no per-item fee generated by surgical intervention in the UK. It is already known that there is a large disparity in rates of elective resection after uncomplicated diverticulitis: up to 40% of patients in Switzerland admitted with uncomplicated diverticulitis undergo elective interval resection10 compared with less than 5% of patients in Scotland.11 This contrasting approach to diverticulitis management offers the unique opportunity to compare outcomes in Switzerland and Scotland for a subgroup of patients with complicated diverticulitis with initial successful nonoperative management. These patients are assumed to be at the highest risk of recurrence, and, in theory, interval resection offers the highest chance of benefit.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Before beginning data analysis, a study protocol was developed after a planning meeting to discuss and define study methods, including the primary end point, and was attended by all authors in Basel, Switzerland, on June 13, 2017. We performed secondary analysis of fully anonymized inpatient admission data from the National Hospital Statistics of the Swiss Federal Statistical Office and from the Scottish Morbidity Record of the Information Service Division of the National Health Service, Scotland. Quality management of the database by the Information Service Division achieves more than 90% accuracy in main operation coding and 99% accuracy in the linkage of patients’ records.12,13 Similar results were reported for the National Hospital Statistics of Switzerland.14,15 The Privacy Advisory Committee of the Information Service Division of the National Health Service, Scotland, and the Ethical Commission Northwestern and Central Switzerland reviewed and approved the study protocol and waived the need for patient consent because patient data were deidentified. Data were provided in accordance with the official data request and protocol of the Swiss Federal Statistical Office for Switzerland and the Information Service Division of National Health Service Scotland. Disclosure control methods, including exclusion of small-number data, were implemented to protect patient confidentiality where necessary. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline16 when summarizing our results in this article.

After a peer-reviewed binational application process, we obtained data sets of all inpatients from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2015, with an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis of primary colonic diverticulitis or diverticulosis in combination with a complication of acute diverticulitis as the primary diagnosis (eg, peritonitis or sepsis). We classified all main and secondary treatments involving major surgical interventions, including interval resections or nonoperative management (absence of major surgical interventions) with the Swiss Classification of Surgical Procedures and the UK Office of Population Censuses and Survey’s Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures Version, 4th revision.

Procedures

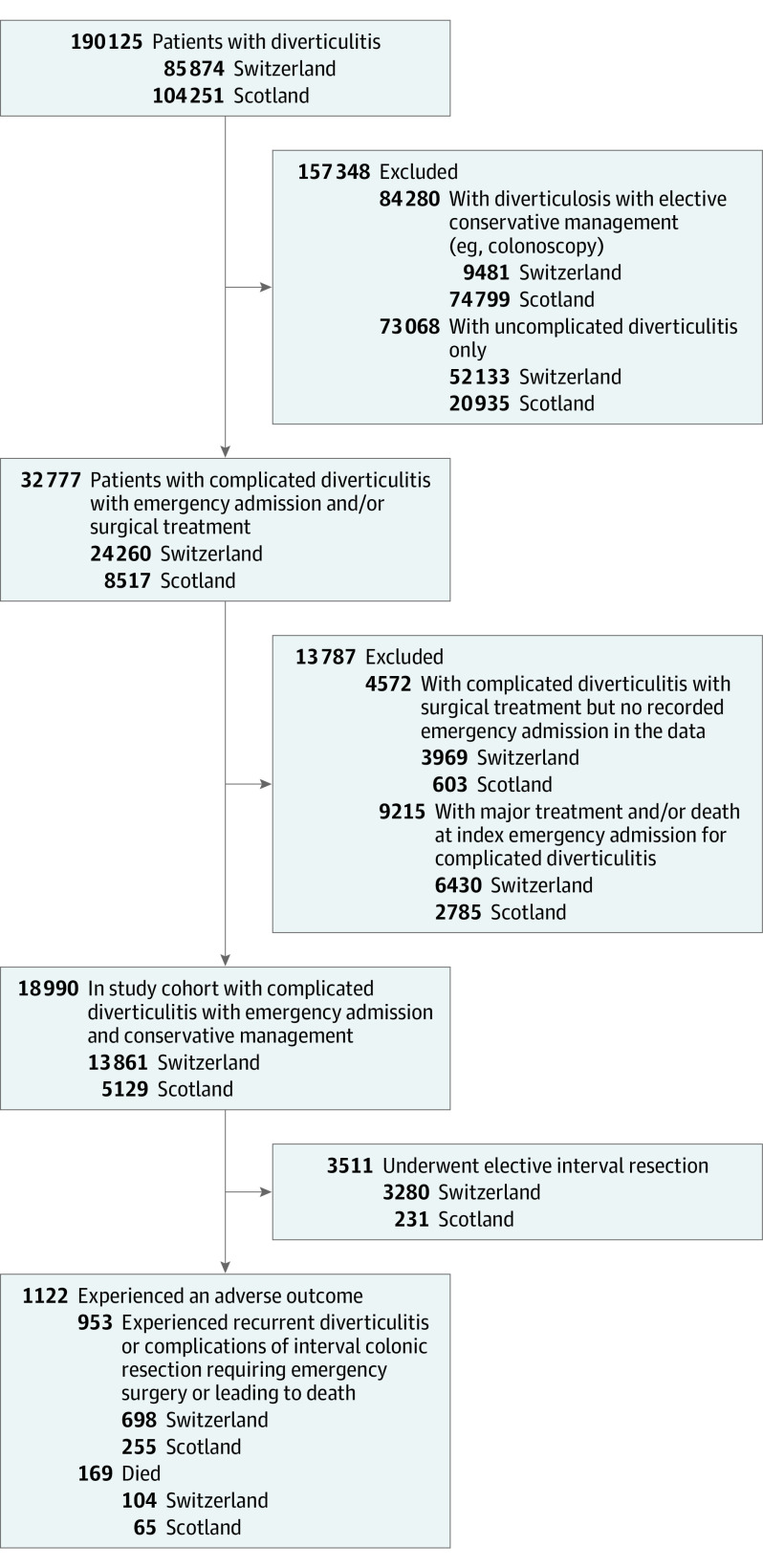

We selected all patients with a first inpatient emergency episode of complicated colonic diverticulitis managed nonoperatively (ICD-10 codes K57.2, K57.4, and K57.8; for details, see eTable 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement) within the available data sets from 2005 to 2015 (ie, with no surgical intervention code during the index admission). Because of the recognized difficulties of extracting subgroups of patients with diverticular disease from administrative data sets, we applied exclusion criteria to each data set in a stepwise manner to exclude nonemergency admissions, incidental diagnosis of diverticulosis, uncomplicated diverticulitis, or diverticulitis of the small bowel (Figure 1). An event was defined as the cohort-defining event if we had no previous record in the database of an emergency admission with a diagnostic code as defined previously. We did not include a screening period to exclude any previous admission for diverticulitis because most emergency admissions for complicated diverticulitis are first admissions, and progression from a first episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis to a subsequent episode of complicated diverticulitis is exceptional.17,18,19 Patients were followed up within the 11-year period using an anonymized unique patient identifier.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Patients With an Admission for Diverticulitis in Switzerland and Scotland From 2005 to 2015.

The primary end point was adverse outcome, defined a priori as any subsequent disease-specific hospital admission for acute diverticulitis or complications from interval elective colon resections, requiring emergency surgery or leading to death. This composite end point was chosen to reflect an important patient perspective (“What is my risk of a serious adverse outcome from this disease or its management?”) and to prevent bias from limiting the analysis to emergency surgery alone, as that bias would exclude patients who were too sick or whose comorbid conditions at presentation made them unable to be considered for an emergency operation and died with nonoperative management alone. The secondary end point was elective interval resection. We adjusted our analyses for established risk factors in the treatment of diverticulitis that were available in both administrative data sets: age at index admission, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index,20,21 social deprivation (defined as low for patients with private insurance in Switzerland and the least-deprived quintile of patients in Scotland defined by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation [a postcode-derived assessment of deprivation incorporating social, economic, and health variables22]), low hospital volume (<7500 admissions per year), and hospital caseload (<100 admissions for diverticulitis per year). Coding for percutaneous radiologic abscess drainage was not available in Switzerland before 2012 and was coded in less than 1% of cases in Scotland; hence, we did not include this factor in our analysis. More granular relevant data, such as body mass index and use of immunosuppressive medication, were not available in these data sets. Details of Scottish and Swiss hospital characteristics are available in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted from February 1, 2018, to October 17, 2019. We summarized patient baseline characteristics providing numbers, proportions, median and interquartile range, and the numbers and percentages of missing observations for relevant variables. Proxy baseline characteristics for the standard of care (hospital overall admission rates and hospital caseload for diverticulitis per year) were assessed on the basis of all inpatients with records in the data sets.

We fitted a logistic regression model to assess the primary outcome with country as the exposure of interest and adjusted for hospital volume and caseload, age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and social deprivation. We calculated odds ratios and 95% CIs of experiencing the primary end point after an initial episode of successful nonoperatively managed complicated diverticulitis. We used generalized estimating equation models with a random intercept to account for a hospital clustering effect. All analyses were performed in R, version 3.5.1.23 All P values were from 2-sided tests, and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

We identified 190 125 inpatients in both countries with a diagnosis of diverticulitis or diverticulosis between 2005 and 2015. After exclusion of elective nonoperative admissions for colonoscopies (n = 84 280) and patients with admissions for uncomplicated disease (n = 73 068), 32 777 patients remained with at least 1 emergency admission for complicated diverticulitis or elective surgery for complicated diverticulitis. Of those patients, 4572 had no previous emergency admission for complicated diverticultis and 9215 underwent immediate surgery and/or died at the index admission, leaving 18 990 patients (n = 5129 in Scotland and n = 13 861 in Switzerland) with initially successful nonoperative treatment of complicated diverticulitis.

Patients with complicated diverticulitis were treated in 64 hospitals in Scotland and 163 hospitals in Switzerland (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The 2 cohorts differed in respect to the following parameters: patients in Scotland compared with Switzerland were more likely to be cared for in hospitals with higher overall patient volume (4930 [96.1%] vs 11 514 [83.1%]) and a higher caseload for diverticulitis (4538 [88.5%] vs 10 057 [72.6%]) (Table 1). A total of 9771 patients were female. The median age category was 70 to 74 years in Scotland and 65 to 69 years in Switzerland.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Hospitals and Patients With Hospital Admission Owing to Complicated Conservatively Managed Diverticulitis in Switzerland and Scotland, 2005-2015.

| Baseline characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Switzerland (n = 13 861) | Scotland (n = 5129) | Both (N = 18 990) | |

| Patients by hospital admission volume | |||

| >7500 Admissions/y | 11 514 (83.1) | 4930 (96.1) | 16 444 (86.6) |

| ≤7500 Admissions/y | 2347 (16.9) | 198 (3.9) | 2545 (13.4) |

| Missing | NA | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.01) |

| Patients by hospital diverticulitis caseload | |||

| >100 Cases/y | 10 057 (72.6) | 4538 (88.5) | 14 595 (76.9) |

| ≤100 Cases/y | 3804 (27.4) | 590 (11.5) | 4394 (23.1) |

| Missing | NA | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.01) |

| Age | |||

| Median age category, ya | 65-69 | 70-74 | 65-69 |

| Patients in age groups, y | |||

| <50 | 2491 (18.0) | 654 (12.8) | 3145 (16.6) |

| ≥50-69 | 5524 (39.9) | 1736 (33.8) | 7260 (38.2) |

| ≥70 | 5846 (42.2) | 2739 (51.3) | 8585 (45.2) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 6967 (50.3) | 2804 (54.7) | 9771 (51.5) |

| Male | 6894 (49.8) | 2325 (45.3) | 9219 (48.6) |

| CCI | |||

| 0 | 10 714 (77.3) | 3820 (74.5) | 14 534 (76.5) |

| 1 | 1109 (8.0) | 538 (10.5) | 1647 (8.7) |

| ≥2 | 2038 (14.7) | 771 (15.) | 2809 (14.8) |

| Deprivationb | |||

| High | 9810 (70.8) | 4046 (78.9) | 13 856 (73.0) |

| Low | 4051 (29.2) | 1083 (21.1) | 5134 (27.0) |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; NA, not applicable.

Age was available in age categories of 5 years, starting 5 to 9 years through more than 94 years.

Deprivation was assumed in Switzerland for patients with only basic mandatory health insurance and in Scotland for the 4 most deprived quintiles of patients defined by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (a postcode-derived assessment of deprivation incorporating social, economic, and health variables).

Median follow-up time was 57 months (interquartile range, 27-91 months) in Scottish patients and 53 months (interquartile range, 24-90 months) in Swiss patients. Incidence of hospital admissions for complicated as well as uncomplicated diverticulitis during the entire period was lower in each year in Scotland compared with Switzerland. For complicated disease, the mean incidence was 1.474 per 10 000 people in Scotland and 2.804 per 10 000 people in Switzerland (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

The percentage of patients with at least 1 hospital readmission during the study period was similar: 35.6% of patients in Scotland (n = 1827) and 36.8% of patients in Switzerland (n = 5095). The median number of readmissions did not differ between the 2 health care systems, neither for patients who did reach the end point (1) nor for those who did not reach the end point (0). There was a trend at low numbers for more readmissions in the group of patients who did not reach the end point in Scotland compared with Switzerland (range, 0-15 vs 0-6) (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Of all patients with initially successful nonoperative treatment of complicated diverticulitis, 255 patients (5.0%) in Scotland and 698 patients (5.0%) in Switzerland experienced the primary end point (odds ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.81-1.19) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Age, sex, hospital volume, or diverticulitis caseload were not statistically significantly associated with the primary outcome in multivariate analysis.

Table 2. Risk of Recurrent Diverticulitis Leading to Emergency Surgery or Death in Patients With Initial Conservatively Managed Diverticulitis in Switzerland and Scotland, 2005-2015.

| Characteristic | Model with no hospital clustering effect | Model with hospital clustering effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Switzerland (vs Scotland) | 0.98 (0.85-1.15) | .83 | 0.98 (0.81-1.19) | .86 |

| Hospital admission volume (≤7500 admissions/y vs >7500 admissions/y) | 1.21 (0.94-1.56) | .13 | 1.21 (0.86-1.70) | .27 |

| Hospital diverticulitis caseload (≤100 cases/y vs >100 cases/y) | 1.07 (0.86-1.31) | .54 | 1.07 (0.80-1.43) | .66 |

| Age (per 5-y age category) | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | .73 | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | .76 |

| Male sex | 0.87 (0.76-0.99) | .04 | 0.87 (0.74-1.01) | .06 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (per unit increase) | 1.04 (0.99-1.08) | .07 | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | .03 |

| Deprivation (yes or no)a | 0.98 (0.84-1.13) | .76 | 0.98 (0.83-1.15) | .79 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Deprivation was assumed in Switzerland for patients with only basic mandatory health insurance and in Scotland for the 4 most deprived quintiles of patients defined by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (a postcode-derived assessment of deprivation incorporating social, economic, and health variables).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curve of Problematic Recurrence.

Time to readmission with problematic recurrence defined as diverticulitis leading to emergency surgery or death or similar complication of elective interval resection. Shaded areas indicate 95% CIs.

Patients with a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index were more likely to experience emergency surgical intervention or to die, but this difference was only marginally statistically significant (odds ratio, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08). Models accounting for hospital clustering effects gave similar estimates. Death after readmission from recurrent complicated diverticulitis after the index hospitalization was less frequent (odds ratio, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.47-0.91) in Switzerland (104 patients [0.8%]) than Scotland (65 patients [1.3%]) (eTable 6 in the Supplement). An additional analysis accounting for interactions between health care system and hospital size as well as Charlson Comorbidity Index and age found no clinically important differences (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Elective interval resection after successful nonoperative treatment of complicated diverticulitis was less frequent in Scotland (231 patients [4.5%]) compared with Switzerland (3280 patients [23.7%]) Of these patients, 13 (5.6%) in Scotland and 176 (5.4%) in Switzerland experienced the primary end point of adverse outcome (emergency reoperation or death). Death alone after elective interval resection was rare, with 2 fatalities in patients in Scotland (0.9%) and 28 in Switzerland (0.9%).

Discussion

Diverticulitis can cause life-threatening sepsis and recurs in a small number of patients. One goal of elective surgical intervention after an episode of nonoperatively managed diverticulitis is to prevent severe recurrence; patients with complicated diverticulitis are at higher risk of severe recurrence. However, colorectal surgery carries a risk of serious morbidity and death24,25,26,27; hence, to be effective, the benefits of elective preventive colonic resection should outweigh its risks.

This population-based analysis of patients treated in Scotland and Switzerland with an episode of complicated diverticulitis managed nonoperatively found no difference in the primary end point of emergency readmission requiring surgery and/or leading to inpatient death despite a 5-fold difference in rates of elective interval resection. The overall risk for the primary end point in either country was low, even in this subgroup perceived to be at higher risk of recurrence, supporting the recent movement toward more conservative management of diverticulitis and careful selection of patients for elective surgery.28 Mortality was lower in Switzerland, but absolute numbers in both countries were very low and almost identical in per-head-of-population terms; this difference might be associated with older age and greater comorbidity in the Scottish cohort or, in a limited way, with higher elective resection rates in Switzerland, but it is more likely to be associated with a higher rate of diagnosis in Switzerland.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this analysis include the comprehensiveness of the data from 2 national health care systems over a long period and the relatively high number of patients, with adjustment for key hospital and patient-related covariates. Most important, this analysis is a direct comparison of 2 health care systems at opposite ends of European health care expenditures with very different philosophies of surgical intervention for a highly prevalent condition, as evidenced by a 10-fold difference in the per-population rate of elective surgery for diverticular disease.10,11

Our study also has relevant limitations. Administrative data have inherent limitations of granularity and variation in coding and classification of hospital-based outcomes over time, and relevant well-known confounders, such as overweight or use of immunosuppressive medication, were not available. We did not have information on previous patient history prior to the formation of our cohort. Definitions of some variables (eg, deprivation) were different in each country. The large difference in the incidence of complicated diverticulitis between the 2 health care systems and the difference in mean age probably is associated with the greater availability of imaging (especially computed tomographic scan) in Switzerland compared with Scotland during the study. Assuming similar overall disease prevalence in 2 developed European countries, this bias would enrich for relatively more severe cases in the Scottish cohort; however, we did not find poorer outcomes at lower resection rates in this group. Finally, our study contains no information on outpatient management, as this was not available in the data sets. We recognize that ongoing symptoms are an important indication for elective interval surgery in selected patients, most obviously those with stricture or fistula. However, we contend that a 5-fold to 10-fold difference in the rate of symptomatic patients in the 2 countries is an unlikely explanation for the large difference in surgical intervention rates, particularly when reports indicate that up to one-third of patients appear to show no symptomatic benefit from resection.29

Our findings are in agreement with those of other large population-based analyses, which could not confirm any association between interval resections and rates of emergency surgery for diverticulitis, although these studies did not differentiate between complicated and uncomplicated diverticulitis.30,31 This finding may be explained by the relatively small risk of recurrent complicated diverticulitis. Epidemiologic data indicate that only 1 in 10 patients with a perforated diverticulitis has had a previous admission for diverticulitis, limiting the reach of any prophylactic surgery.17 Despite this fact, high elective resection rates persist in the Swiss health care system. The high number and the mix of private and publicly funded hospitals in Switzerland may incentivize more surgical interventions to use hospital capacity.10 There is no reason to think that the United States is any different, where half of all elective colonic resections are undertaken for diverticular disease and the rate of surgery appears to be rising despite revised guidelines.31,32,33

Conclusions

This population-based analysis in 2 contrasting national health care systems could not detect a difference in the rate of emergency readmission requiring surgery and/or leading to inpatient death after an episode of complicated diverticulitis managed nonoperatively despite a 5-fold difference in the rate of elective interval resection. Our study results challenge the appropriateness of recommendations for prophylactic surgery after a successfully nonoperatively managed episode of complicated diverticulitis, as, for example, expressed in the German Interdisciplinary and the American Society of Colon and Rectum Surgeons guidelines.6,7

eTable 1. ICD Diverticulitis Codes

eTable 2. Additional ICD Diverticulitis Codes for Combination of Complication as Main Diagnosis and Diverticulitis Code (According eTable 1)

eTable 3. Hospital Characteristics and Expertise of All Hospitals With Diverticulitis Cases, by Country

eTable 4. Annual Unadjusted Incidence Rates of Complicated and Uncomplicated Diverticulitis From 2005 to 2015 in Switzerland and Scotland

eTable 5. Readmissions in Switzerland and Scotland After an Initial Episode of Successful Conservative Management of Diverticulitis Stratified by a later Event of Emergency Surgery or Death

eTable 6. Marginal Model for Problematic Recurrence Leading to Death, in Patients After a First Conservatively Managed Episode of Complicated Diverticulitis in the Swiss and Scottish Health Care System

eTable 7. a) Multiple Logistic Regression for Problematic Recurrence With Scotland Instead of Switzerland as Reference Level, and Including Interaction Terms; b) Model Accounting for Hospital Clustering, With Scotland as Reference Level, and Including Interaction Terms; c) Multiple Logistic Regression and GEE for Recurrence With Death, Using Scotland as Reference Level, and Including Interaction Terms; d) Multiple Logistic Regression and GEE for Recurrence With Death, Using Scotland as Reference Level, and Including Interaction Terms Accounting for Hospital Clustering

References

- 1.Bharucha AE, Parthasarathy G, Ditah I, et al. Temporal trends in the incidence and natural history of diverticulitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(11):1589-1596. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humes DJ, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Fleming KM, Simpson J, Spiller RC, West J. A population-based study of perforated diverticular disease incidence and associated mortality. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1198-1205. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klarenbeek BR, Samuels M, van der Wal MA, van der Peet DL, Meijerink WJ, Cuesta MA. Indications for elective sigmoid resection in diverticular disease. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):670-674. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d3447d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stocchi L. Current indications and role of surgery in the management of sigmoid diverticulitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(7):804-817. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i7.804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feingold D, Steele SR, Lee S, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of sigmoid diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(3):284-294. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreyer AG, Layer G; German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS); German Society of General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV); in collaboration with the German Radiology Society (DRG) . S2k guidelines for diverticular disease and diverticulitis: diagnosis, classification, and therapy for the radiologist. Rofo. 2015;187(8):676-684. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1399526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fozard JB, Armitage NC, Schofield JB, Jones OM; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland . ACPGBI position statement on elective resection for diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(suppl 3):1-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vennix S, Morton DG, Hahnloser D, Lange JF, Bemelman WA; Research Committee of the European Society of Coloproctocology . Systematic review of evidence and consensus on diverticulitis: an analysis of national and international guidelines. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(11):866-878. doi: 10.1111/codi.12659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Strauss und Torney M, Thommen S, Dell-Kuster S, et al. Surgical treatment of uncomplicated diverticulitis in Switzerland: comparison of population-based data over two time periods. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19(9):840-850. doi: 10.1111/codi.13670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paterson HM, Arnott ID, Nicholls RJ, et al. Diverticular disease in Scotland: 2000-2010. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(4):329-334. doi: 10.1111/codi.12811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh D, Smalls M, Boyd J. Electronic health summaries—building on the foundation of Scottish Record Linkage system. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2001;84(pt 2):1212-1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Public Health Scotland. Data quality assurance. Accessed December 10, 2019. https://www.isdscotland.org/Products-and-Services/Data-Quality/About-Data-Quality-Assurance.asp

- 14.Zellweger U, Junker C, Bopp M; Swiss National Cohort Study Group . Cause of death coding in Switzerland: evaluation based on a nationwide individual linkage of mortality and hospital in-patient records. Popul Health Metr. 2019;17(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12963-019-0182-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eidgenossenschaft S. Medizinische statistik der krankenhäuser In: Detailkonzept Version 12. Dezember 2005. Vol 1 Swiss Federal Statistical Office; 2005:47. [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman J, Davies M, Wolff B, et al. Complicated diverticulitis: is it time to rethink the rules? Ann Surg. 2005;242(4):576-581. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000184843.89836.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chautems RC, Ambrosetti P, Ludwig A, Mermillod B, Morel P, Soravia C. Long-term follow-up after first acute episode of sigmoid diverticulitis: is surgery mandatory?: a prospective study of 118 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(7):962-966. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6336-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haglund U, Hellberg R, Johnsén C, Hultén L. Complicated diverticular disease of the sigmoid colon: an analysis of short and long term outcome in 392 patients. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1979;68(2):41-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245-1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scottish Government. Introducing the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2016. Published August 31, 2016. Accessed May 19, 2019. https://www2.gov.scot/Resource/0050/00504809.pdf

- 23.R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Killingback M, Barron PE, Dent OF. Elective surgery for diverticular disease: an audit of surgical pathology and treatment. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(7):530-536. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2004.03071.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pessaux P, Muscari F, Ouellet JF, et al. Risk factors for mortality and morbidity after elective sigmoid resection for diverticulitis: prospective multicenter multivariate analysis of 582 patients. World J Surg. 2004;28(1):92-96. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7146-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirchhoff P, Matz D, Dincler S, Buchmann P. Predictive risk factors for intra- and postoperative complications in 526 laparoscopic sigmoid resections due to recurrent diverticulitis: a multivariate analysis. World J Surg. 2011;35(3):677-683. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0889-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose J, Parina RP, Faiz O, Chang DC, Talamini MA. Long-term outcomes after initial presentation of diverticulitis. Ann Surg. 2015;262(6):1046-1053. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biondo S. The diminishing role of surgery for acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2019;106(4):308-309. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolkenstein HE, Consten ECJ, van der Palen J, et al. ; Dutch Diverticular Disease (3D) Collaborative Study Group . Long-term outcome of surgery versus conservative management for recurrent and ongoing complaints after an episode of diverticulitis: 5-year follow-up results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial (DIRECT-Trial). Ann Surg. 2019;269(4):612-620. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Etzioni DA, Mack TM, Beart RW Jr, Kaiser AM. Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998-2005: changing patterns of disease and treatment. Ann Surg. 2009;249(2):210-217. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181952888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simianu VV, Strate LL, Billingham RP, et al. The impact of elective colon resection on rates of emergency surgery for diverticulitis. Ann Surg. 2016;263(1):123-129. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Arendonk KJ, Tymitz KM, Gearhart SL, Stem M, Lidor AO. Outcomes and costs of elective surgery for diverticular disease: a comparison with other diseases requiring colectomy. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):316-321. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strassle PD, Kinlaw AC, Chaumont N, et al. Rates of elective colectomy for diverticulitis continued to increase after 2006 guideline change. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(6):1679-1681. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. ICD Diverticulitis Codes

eTable 2. Additional ICD Diverticulitis Codes for Combination of Complication as Main Diagnosis and Diverticulitis Code (According eTable 1)

eTable 3. Hospital Characteristics and Expertise of All Hospitals With Diverticulitis Cases, by Country

eTable 4. Annual Unadjusted Incidence Rates of Complicated and Uncomplicated Diverticulitis From 2005 to 2015 in Switzerland and Scotland

eTable 5. Readmissions in Switzerland and Scotland After an Initial Episode of Successful Conservative Management of Diverticulitis Stratified by a later Event of Emergency Surgery or Death

eTable 6. Marginal Model for Problematic Recurrence Leading to Death, in Patients After a First Conservatively Managed Episode of Complicated Diverticulitis in the Swiss and Scottish Health Care System

eTable 7. a) Multiple Logistic Regression for Problematic Recurrence With Scotland Instead of Switzerland as Reference Level, and Including Interaction Terms; b) Model Accounting for Hospital Clustering, With Scotland as Reference Level, and Including Interaction Terms; c) Multiple Logistic Regression and GEE for Recurrence With Death, Using Scotland as Reference Level, and Including Interaction Terms; d) Multiple Logistic Regression and GEE for Recurrence With Death, Using Scotland as Reference Level, and Including Interaction Terms Accounting for Hospital Clustering