Abstract

Purpose

Exome and genome sequencing (ES/GS) are performed frequently in patients with congenital anomalies, developmental delay, or intellectual disability (CA/DD/ID), but the impact of results from ES/GS on clinical management and patient outcomes is not well characterized. A systematic evidence review (SER) can support future evidence-based guideline development for use of ES/GS in this patient population.

Methods

We undertook an SER to identify primary literature from January 2007 to March 2019 describing health, clinical, reproductive, and psychosocial outcomes resulting from ES/GS in patients with CA/DD/ID. A narrative synthesis of results was performed.

Results

We retrieved 2654 publications for full-text review from 7178 articles. Only 167 articles met our inclusion criteria, and these were primarily case reports or small case series of fewer than 20 patients. The most frequently reported outcomes from ES/GS were changes to clinical management or reproductive decision-making. Two studies reported on the reduction of mortality or morbidity or impact on quality of life following ES/GS.

Conclusion

There is evidence that ES/GS for patients with CA/DD/ID informs clinical and reproductive decision-making, which could lead to improved outcomes for patients and their family members. Further research is needed to generate evidence regarding health outcomes to inform robust guidelines regarding ES/GS in the care of patients with CA/DD/ID.

Keywords: clinical genetics, exome sequencing, systematic evidence review, congenital anomalies, intellectual disability

INTRODUCTION

Exome and genome sequencing (ES/GS) are relatively new clinical diagnostic genetic testing platforms for identifying a genetic etiology among individuals with congenital anomalies (CA), developmental delay (DD), or intellectual disability (ID). CAs are structural or functional abnormalities usually evident at birth, or shortly thereafter, and can be consequential to an individual’s life expectancy, health status, physical or social functioning, and typically require medical intervention. DD/ID are common features of a wide variety of genetic syndromes, or they could be isolated findings. Due to phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity associated with CA/DD/ID, establishing a syndromic diagnosis based on clinical signs and symptoms can be challenging, particularly in the newborn period. Furthermore, some CAs may not be easily diagnosed in the newborn period but could contribute to a lifelong burden to affected children and families. Clinical genetic testing can assist clinicians in confirming or establishing a clinical diagnosis that may lead to changes in clinical management, obviate the need for further testing, or end the diagnostic odyssey, which may improve outcomes for the patient and family.

Current standard practice, based on recommendations from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), is to perform chromosomal microarray (CMA) as the first-tier genetic test for individuals with CA/DD/ID.1 Diagnostic yield for CMA has typically focused on cohorts of mixed phenotypes of CA/DD/ID, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Yields averaged 12.2% in the early literature.2,3 More recent studies on cohorts of patients with CA/DD/ID have documented diagnostic yields ranging from 16% to 28%.4–6 As a result, CMA is a well-established tool in clinical practice, yet this testing will not capture single-nucleotide variations (SNVs) or small insertion/deletions (indels), smaller structural variants, and other pathogenic variant types contributing to CA/DD/ID.

The recommendations to perform CMA as a first-line test for CA/DD/ID occurred prior to the widespread availability of clinical ES/GS. Studies of ES/GS for these patients have shown there is an even larger diagnostic yield ranging from 28% to 68%.7–12 Notably, most studies included patients who had negative findings with CMA, demonstrating a higher yield for ES/GS compared with CMA.9 Higher yields have been observed when ES/GS is used as a first-line test.7,11

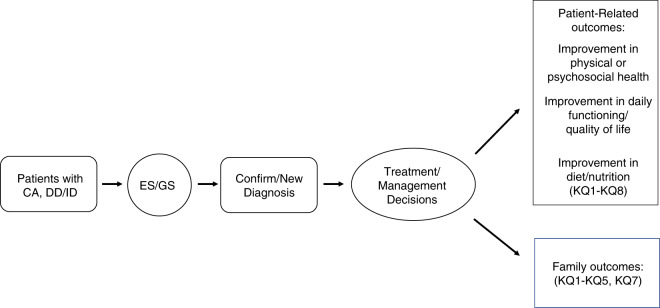

Establishing a diagnosis for patients with CA/DD/ID through genetic testing generally, and ES/GS specifically, can impact clinical management and patient-related outcomes (Figure 1). For example, early infantile epilepsy is a phenotypically and genetically heterogeneous disorder that may result from structural brain anomalies or functional abnormalities. Patients may be treated with diet, antiepileptics, or other systemic medications depending on their specific diagnosis; patients with West syndrome may be treated with adrenocorticotrophin, vigabatrin, or pyridoxine and biotin, while patients with Otahara syndrome who fail to respond adequately to antiepileptics may be treated with ketogenic diet or neurosurgery in the case of structural brain malformations.13

Fig. 1. Analytic framework for evaluating outcomes of exome/genome sequencing (ES/GS) for patients with congenital anomalies (CA) or developmental delay/intellectual disability (DD/ID).

KQ key question.

The specific nature and frequency of outcomes describing clinical and personal utility resulting from ES/GS for patients with CA/DD/ID have not been well characterized; therefore, we initiated a systematic evidence review of the existing literature to document these. We focused our attention on the reported and demonstrated impact of ES/GS on clinical management, including anticipatory guidance, physical and social well-being, and the ability to influence reproductive decision-making for the patient or their family members. We summarize the extent and limitations of evidence for these outcomes in this patient population and include suggestions for prospective evidence generation to inform both clinical and personal utility resulting from ES/GS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In 2017, this ACMG working group was established to assess patient and clinical outcomes of ES/GS in patients with CA/DD/ID. Workgroup participants were members of ACMG and included board-certified medical geneticists specializing in adult and pediatric clinical genetics (L.D., J.G., S.E.H., D.T.M., E.M.P., A.C.-H.T., M.T.S.) and laboratory genetics (J.S., M.C.S.), and a methodologist (J.M.). None of the working group members had any conflicts of interest, according to ACMG policy. To address the overarching research question, “What is the utility of exome/genome sequencing of patients with CA/DD/ID?” the authors developed a description of the targeted population, intervention, comparator, outcomes, timing, and setting (PICOTS) (Table 1). In response to the PICOTS, key questions (KQs) were developed to structure and inform the overall goals of the project (Table 1). The KQs corresponded to the health outcomes, clinical management, reproductive planning/issues, and health-care utilization from the patient, family, and provider perspectives.

Table 1.

PICOTS and key questions.

| PICOTS | Key questions |

|---|---|

|

•Population: patients with one or more (1+) CA (functional and/or structural) evident/documented prior to 1 year of age, or DD/ID evident/documented at or before 18 years of age •Intervention: ES or GS •Comparator: no ES/GS performed •Outcomes: patient-centered (health-related, behavioral/psychosocial, reproductive), provider-centered (change of patient management, change in length of time to diagnosis/treatment), family-centered (health-related, behavioral/psychosocial, reproductive) •Timeframe: any, as long as patient met inclusion criteria •Setting: any clinical setting in community and/or academic institutions |

•KQ1: Does ES/GS of patients with CA, DD/ID impact health-related outcomes of morbidity, health status, functional status, or mortality, for the patient or their at-risk family members, compared with not having ES/GS? •KQ2: Does ES/GS of patients with CA, DD/ID impact secondary health outcomes, such as quality of life, length of hospitalization, or health-care utilization, for the patient or their at-risk family members, compared with not having ES/GS? •KQ3: Does ES/GS of patients with CA, DD/ID impact reproductive decision-making for the patient or their at-risk family members, such as deciding not to become pregnant, use assisted reproductive technologies with/without preimplantation genetic testing and/or additional fetal genetic testing, terminate a pregnancy, adopt, or use donor sperm/eggs, compared with not having ES/GS? •KQ4: Does ES/GS of patients with CA, DD/ID impact behavioral and/or psychosocial outcomes for the patient or their family/caregivers, such as stress, anxiety, depression, communication of test results to family and/or support network, compared with not having ES/GS? •KQ5: Does ES/GS of patients with CA, DD/ID impact clinical management for the patient or their at-risk family members through a change in medication and/or nutritional supplementation, a change in diagnostic test/procedure ordering, or referral to specialists, compared with not having ES/GS? •KQ6: Does genome-level sequencing of patients with congenital anomalies reduce the time to diagnosis, compared with not having genome-level sequencing? •KQ7: Does ES/GS of patients with CA, DD/ID impact identification of additional disorders (e.g., ACMG59) for the patient or the patient’s immediate family (i.e., parent[s], sibling[s]) or other at-risk family members, compared with not having ES/GS? •KQ8: Are there additional or separate harms from ES/GS compared with other forms of genetic testing? |

ACMG American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, CA congenital anomalies, DD/ID developmental delay/intellectual disability, ES exome sequencing, GS genome sequencing, PICOTS population, intervention, comparator, outcomes, timing, and setting.

Search strategy

The following search strategy was used to query the PubMed database from 1 January 2007 to 26 April 2018 and was updated on 1 March 2019, with English and Human filters:

(((“whole exome” OR “whole genome”) AND sequencing) OR (WES) OR (WGS)) AND (clinical OR utility OR outcome OR treatment OR care OR medication OR intervention OR counseling OR stress OR relief OR depression OR anxiety OR psychological OR communication OR “quality of life” OR quality OR pregnancy OR prenatal OR carrier OR testing OR test OR reproductive OR anxiety OR decision OR referral OR surgery OR procedure OR management OR outcome)) NOT (bacterial OR microbial OR isolate OR isolates OR virulence OR infection)

Each publication identified by the search strategy underwent dual review for eligibility by a team of nine reviewers in a two-step process: title/abstract screening followed by full-text review using the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in Table 1. Although CA may manifest postinfancy, we limited inclusion of studies to those where CA had onset prior to age 1 year and DD/ID had onset prior to age 18 years. Studies that failed to meet inclusion criteria were excluded in title/abstract review or in full-text review. Discordance between reviewers at each step was resolved through discussion, with adjudication by the methodologist or other group members, if needed. We identified additional publications through review of the references cited by included studies. We specifically sought to identify gray literature; that is, relevant data captured in laboratory and/or hospital registries of patients with CA/DD/ID, presented at conferences, and/or published as conference abstracts. Studies presenting only hypothetical impacts to patient or family management stemming from ES/GS, or studies that presented only the diagnostic yield of ES/GS were excluded.

Systematic Review Data Repository

The Systematic Review Data Repository (SRDR) (https://srdr.ahrq.gov/), a freely available web-based platform for data extraction and management of systematic evidence reviews was used to facilitate the evidence review. Individual SRDR projects were created for the title and abstract screening, full-text review, and data extraction of studies. Studies were uploaded in duplicate to SRDR and randomly assigned to reviewers for each stage of the evidence review. Extraction forms were developed separately. Specifically, the extracted data included study design details, sequencing method, patient population information (i.e., CA/DD/ID, age), and outcomes related to ES/GS, including harms associated with their use. Diagnostic yield was not extracted nor evaluated for this study.

Patient and clinical outcomes

We assessed the extent to which studies reported a measurable impact on health, reproductive, psychological, and behavioral outcomes for the patient or the patient’s family, including:

Morbidity, mortality, change in health status or function, quality of life, or duration of hospitalization

Reproductive decision-making for the patient or their immediate family

Change in clinical management such as recommending medication/nutritional supplementation, ordering diagnostic tests or procedures, and referring to specialists

Psychosocial and behavioral outcomes such as distress, anxiety or depression, or change in communication patterns among the patient and their family/caregivers

Data analysis

Extracted data were summarized in several ways. Counts were calculated for study characteristics (e.g., country, year of publication) for publications with 20 or more patients. We extracted evidence of outcomes of interest from each study and calculated the proportion of unique patients (or the family of a patient) with a reported change in management or reproductive planning. A narrative synthesis was performed due to substantial heterogeneity between studies and because available data precluded quantitative analysis.

RESULTS

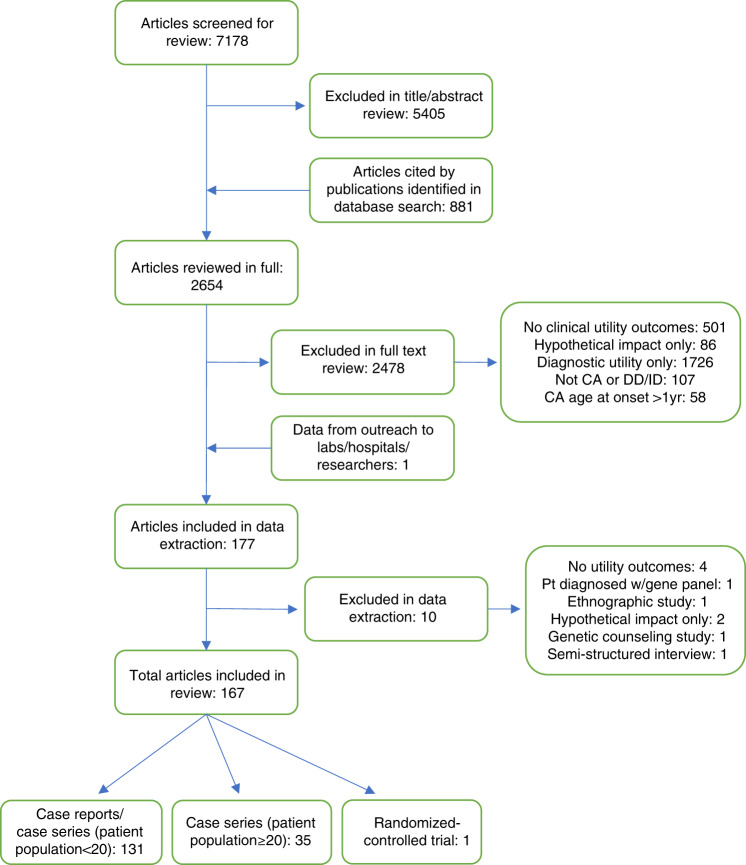

The database searches identified 7178 publications. During title and abstract screening, 5405 studies were excluded based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Figure 2, Table 2). Additional studies, mostly case reports, were identified through exhaustive review of citations in other articles and conference abstract searches (n = 881); a total of 2654 publications were retrieved for full-text review. Following review of eligibility, 177 studies were selected for data extraction. During the data extraction process, 10 additional studies were removed. Outreach to hospital and clinical laboratories, and authors of relevant meeting presentations and abstracts, resulted in the inclusion of data from one additional source.14 In sum, 167 relevant studies, including case reports, were identified.

Fig. 2. PRISMA flowchart.

CA congenital anomalies, DD/ID developmental delay/intellectual disability.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Patients with CA with age of onset ≤1 year, patients with DD/ID diagnosed by 18 years | Patients with CA and age of onset >1 year; patients with isolated, nonsyndromic autism without presence of CA or DD/ID |

| Primary English-language literature including case studies, case series, case–control studies, observational studies, randomized controlled trials | Review articles, commentaries, editorials, basic research (e.g., animal, cell model studies); non-English studies |

| ES or GS | Targeted (less than exome-level) panel sequencing, non-genome-level sequencing performed |

| Health and clinical management outcomes reported | No health or clinical management outcomes presented or are hypothetical; only diagnostic yield reported |

| ES/GS in patients without CA or DD/ID for infectious disease or cancer | |

| ES/GS in patients without CA or DD/ID for prenatal testing or prenatal genetic diagnostics |

CA congenital anomalies, DD/ID developmental delay/intellectual disability, ES exome sequencing, GS genome sequencing.

Study characteristics

The majority of included studies were case reports or case series with small populations (n < 20 patients). Table 2 summarizes the study characteristics of the 36 included publications with a patient population ≥20. Sample size reported corresponds only to the number of patients in each study reported to have received ES/GS. In one study,15 the patient population was reported as the number of families that participated. For the 36 studies characterized in Table 3, the sample size ranged from 22 to 278 patients. Most studies reported ES results (n = 27), while 7 studies reported health or clinical management outcomes following GS; two studies used both methods. Studies were set predominantly in the United States (n = 15), but overall, reflected the growing international use of sequencing technology in patients with CA/DD/ID.

Table 3.

Summary of health and clinical outcomes in 36 case series studies with ≥20 patients.

| Authors | Publication year | Country | Timing | N | Indication | Inclusion | Exclusion | ES or GS | Clinical management outcomes | Reproductive outcomes | Behavioral or psychosocial outcomes | Harms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anazi et al.17 | 2017 | Saudi Arabia | NR | 232 | ID | Documented IQ ≤ 70; children <5 years w/physician-assessed DD/ID | NR | ES | 1 pt started on chelation tx w/excellent response in terms of manganese level | NR | NR | NR |

| Baldridge et al.24 | 2017 | USA | 3/2012–1/2015 | 155 | CA | NR | NR | ES | 84/155, 54%: additional dx studies (molecular, imaging, biochem); 8/155, 0.6%: clin mgmt directly impacted (change in med, surg procedures, referrals to specialists); 36/155, 23%: enrolled in research studies | NR | NR | 2/155, 1%: cases of nonpaternity requiring ethics consultation and altered strategies for pretest couns |

| Bekheirnia et al.34 | 2017 | USA | NR | 112 (62 families) | CA | Pts w/nonsyndromic forms of CAKUT; pts w/syndromic forms of CAKUT w/o identified genetic etiology | Pts w/syndromic forms of CAKUT w/known genetic etiology; pts w/nonsyndromic and nonfamilial forms of VUR | ES | 3/62, 5% families: pt mgmt changed: 1/62, 2% families: pt tapered on immunosuppressants; 1/62, 2% families: pt referred for hearing screening; 1/62, 2% families: pt referred to ophthalm w/specialty in genetic disorders, evals found congenital optic nerve abnormalities | NR | NR | NR |

| Bick et al.42 | 2017 | USA | 2010–2013 | 22 | CA/DD/ID | Pts w/std dx testing; apparently undiagnosed monogenic genetic disorder; molecular dx thought to aid physicians/families w/med decision-making/mgmt or fam planning; sufficient samples to undertake genomic testing & follow-up testing as needed; cost of GS appeared less costly than testing individual genes for phenotype | NR | GS | 6/22, 27%: change in pt mgmt. (in total): 4/22, 18%: medication change/initiation/supported use of; 6/22, 27%: screening/testing/surveillance | 8/22, 36%: reported as risk of recurrence for parents | NR | NR |

| Bourchany et al.35 | 2017 | France | NR | 29 | CA/DD/ID | Undiagnosed DD/ID and (1) an ongoing preg of at-risk relatives requesting genetic couns; (2) hospitalization in an ICU w/a diagnostic request for guiding care | NR | ES | 5/29, 17%: changed pt mgmt. (total): 2/29, 7%: added med; 1/29, 3%: investigated systemic involvement; 2/29, 7%: inclusion in a clin trial | 12/29, 41%: enabled prenatal couns/testing; 13/29, 45%: enabled reproductive planning; 12/29, 41%: enabled prenatal couns/testing; 2/29, 7%: used prenatal dx in subsequent pregnancies to have unaffected fetuses | NR | NR |

| Cordoba et al.39 | 2018 | Argentina | NR | 40 | CA/DD/ID | Consecutive series of 40 pts selected for ES from a neurogenetic clinic of a tertiary hospital; presence of typical findings of known neurogenetic diseases and/or hints of monogenic etiology such as familial aggregation or chronic and progressive course | NR | ES | 13/40, 32.5%: change pt mgmt. (in total): 4/40, 10%: trial of new med; 2/40, 5%: avoid specific drugs; 1/40, 3%: monitoring for hypogonadism | NR | NR | NR |

| Dixon-Salazar et al.16 | 2012 | Middle East/North Africa/Central Asia | NR | 118 | CA/DD/ID | NR | NR | ES | 1/118, 0.1%: re-eval of pt‘s fam for GJC2-assoc disease; 1/118, 0.1%: MAN2B1 variant pt care redirected & provided fam guidance; 1/118, 0.1%: withdrew vitamin E tx | 10/118, 8%: genetic couns, prenatal dx options, and carrier testing were altered after dx | NR | NR |

| Evers et al.36 | 2017 | Germany | 1/2013–12/2015 | 72 | CA/DD/ID | Pts w/DD/ID and/or CA; pts w/infantile dystonia; pts w/neurometabolic disorder | NR | ES | 8/72, 11% change pt mgmt (in total): 2/72, 3%: change of antiepileptic med in 1 pt, tx w/galactose in 1 pt; 6/72, 8%: initiated surveillance for other disease-associ complications | 4/60, 7% families: decision to undergo additional fetal testing; in 20/21, 95%: families who received reports: the result was important for fam planning, either w/regard to a further preg of the parents or for the future fam planning of their nonaffected children | NR | NR |

| Farnaes et al.20 | 2018 | USA | 7/2016–3/2017 | 42 | CA | Inpatient; <1 year of age; no etiologic dx; possible genetic disease | >1 year of age; discharged/deceased; dx likely to be obtained via clin testing; sx determined not likely to be due to a genetic etiology; parents unavail/refused consent | GS | 5/42, 12%: med change; 4/42, 10%: change in surg; 1/42, 2%: palliative care initiated; 4/42, 10%: change in imaging/procedure; 10/42, 24%: morbidity avoided (comparison to historical/controls); 1/42, 2%: 83–94% decrease in mortality risk compared with historical/control | NR | NR | NR |

| French et al.14 | 2019 | UK | 12/2016–9/2018 | 195 | CA | CA; neuro sx; suspected metabolic disease; surg necrotizing enterocolitis; extreme IUGR; or failure to thrive; unexplained critical illness/clinician request | Prematurity w/o additional features; known trisomies or other genetic dx; trauma; hematological malignancy/oncology; bronchiolitis/respiratory tract infection | GS | 35/195, 18%: change pt mgmt. (in total); 7/195, 4%: initiated palliative care; 5/195, 3%: modified tx; 19/195, 10%: initiated new specialist care; 14/195, 7%: informed existing specialist care | 7/195, 4%: informed subsequent reproductive decisions; 14/195, 7%: informed parents of significant recurrence risk | NR | NR |

| Iglesias et al.26 | 2014 | USA | 10/2011–7/2013 | 115 | CA/DD/ID | Pts clinically evaluated by one of three board-certified clin geneticists and one of six board-certified genetic counselors | NR | ES | 20/115, 17%: change pt mgmt (in total): 3/115, 3%: medication/dietary change/optimization; 3/115, 3%: eval for additional disorders; 2/115, 2%: screening of at-risk fam; 1/115, 1%: provided enrollment information for clin trial; 2/115, 2%: terminated additional/invasive testing; 4/115, 3%: referral to social services/MDA, educational placement/planning, early intervention | 6/115, 5%: “fam planning” including: 3/115, 3%: decision to use PGD in subsequent preg; 1/115, 1%: CVS was undertaken; others not specified | NR | NR |

| Kuperberg et al.31 | 2016 | Israel | 2011–2015 | 57 | CA/DD/ID | Pts of MAGEN clinic suspected as having a monogenic disorder, undiagnosed despite extensive clin, biochem, imaging, and traditional genetic evals, including karyotype, CMA testing for duplicated or deleted segments or for areas of excessive homozygosity, candidate gene sequencing, biopsy if possible, metabolic workup and others as deemed required | NR | ES | 4/57, 7%: immediate change in medication due to ES results; 1/57, 2%: change to ketogenic diet; 2/57, 4%: at-risk fam members underwent genetic testing | 2/57, 4%; pregnant mothers underwent additional fetal testing; 29/57, 51%: families had more accurate genetic counseling | NR | NR |

| Meng et al.8 | 2017 | USA | 2011–2017 | 278 | CA | Age ≤100 days of life at time of testing; referred for ES from December 2011 to January 2017; underwent ES performed as clin service | NR | ES | 53/278, 19%: change pt mgmt (in total): 19/53, 36% pts w/change in mgmt: palliative/withdrawal of life support; 7/53, 13%: initiation/change of medication/diet; 5/53, 9%: initiation/change of procedures; 27/53, 51%: referral to specialists; 21/278, 8%: identification of carrier status/other disorders/risk for disorders | 90 (88.2%) families: genetic counseling | NR | NR |

| Miller et al.37 | 2017 | UK | NR | 40 | CA | Pts w/craniosynostosis; previously investigated by molecular genetic testing with normal findings | Pts w/targeted genetic testing identifying a monogenic cause; pts for whom enrollment into Deciphering Devel Disorders study was considered more appropriate; samples not avail for analysis | ES (n = 37), GS (n = 3) | 7/40, 18%: total change in pt mgmt; 1/40, 3%: commenced prophylactic azithromycin and itraconazol; 1/40, 3%: lifelong monitoring for progressive aortic dilatation; 1/40, 3%: recommendation for coagulation screening prior to any future surg; 1/40, 3%: regular monitoring for secondary complications incl. cardiovascular disease and diabetes; 1/40, 3%: underwent detailed immunological assessment & awaiting donor for stem cell transplant; 1/40, 3%: underwent detailed endocrinology assessment; 1/40, 3%: referral to a clin psych and dietitian to address her eating behaviors | 1/40, 3%: parents considering not to have more children after dx of pt; 1/40, 3%: enrolled in prenatal genetic dx program | NR | NR |

| Nair et al.19 | 2018 | Lebanon | 2015–2017 | 167 | CA/DD/ID | Ped pts referred for genetic couns by PCP | NR | ES | 1/167, 0.6%: fam members of pt w/ACMG59 variant assoc w/sudden death underwent screening & were referred to cardiac specialist for follow-up | NR | NR | NR |

| Nolan and Carlson32 | 2016 | USA | 6/2011–6/2015 | 53 | CA/DD/ID | Pts evaluated in the ped neuro clinic referred for ES | Pts w/out ES | ES | 12/53, 23% changed pt mgmt (in total): 5/53, 9%; medication/drug management; 1/53, 2%; neuroimaging frequency; 1/53, 2%: enrollment in clin trial; 2/53, 4%; testing for pt‘s sibling; 6/53, 11%: referrals to: nephr, cardio, ophthalm, multidisciplinary, hematology, audiology, pulmonology; 1/53, 2%: pt's father referred to cardio | 10/53, 19%: impacted fam planning (not otherwise specified) | 1/53, 2%: referral to support groups | NR |

| Perucca et al.38 | 2017 | Australia | NR | 40 | CA | Pts prospectively enrolled from routine clin practice w/MRI-negative focal epilepsy and a fam hx of febrile seizures or any type of epilepsy in at least one first- or second-degree relative | Pts w/previous genetic testing, severe ID and benign focal epilepsies of childhood | ES | 1/40, 3%: stopped presurg eval; 1/40, 3%: started on perampanel, discontinued carbamazepine | NR | NR | NR |

| Petrikin et al.41 | 2018 | USA | 10/2014–6/2016; follow-up until 11/2016 | 32 (rapid GS + std genetic tests); N = 5 compassionate crossover from std group | CA | Infants age <4 months in NICU/PICU w/illnesses of unknown etiology; genetic test order or genetic consult; major structural CA or ≥3 minor anomalies; abnormal lab test suggesting a genetic disease; abnormal response to standard tx for a major underlying condition | Pts w/previously confirmed genetic dx explaining clin condition; features pathognomonic for a chromosomal aberration | GS | 7/37, 19%: change other than counseling (total); 4/37, 11%: change in subspecialty consult; 1/37, 3%: change in medication; 2/37, 5%: change in procedure; 1/37, 3%: change in diet; 3/37, 8%: change in imaging | 10/37, 27%: genetic or reproductive counseling (not specified) | NR | NR |

| Powis et al.47 | 2018 | USA | NR | 66 | CA/DD/ID | Neonatal (birth–1 mo) pt samples sent for ES at clin lab | NR | ES | 1/66, 2%: patient found to have SOX10 variant; fam withdrew ventilator support, pt expired | 1/66, 2%: mother of pt underwent prenatal testing in subsequent preg, fetus not found to have pathogenic variant & was delivered healthy | NR | NR |

| Sawyer et al.15 | 2016 | Canada | NR | N = 105 families | CA | Pts enrolled in FORGE project | NR | ES | 6/105, 6% families: 3 pts tx adjusted; 3 pts tx initiated | NR | NR | NR |

| Soden et al.27 | 2014 | USA | NR | 119 | CA/DD/ID | Families w/heterogeneous clin conditions | NR | ES, GS | 12/119, 10%: new med/dietary tx; 5/119, 4%: stopped current med/dietary tx; 18/119, 15%: added or changed procedures relating to dx; 1/119, 0.8%: cardio exam for mother of proband | NR | NR | NR |

| Scocchia et al.11 | 2019 | Mexico | NR | 60 | CA/DD/ID | Pts presenting for Illumina iHope prog: referral from ped to dysmorphology clinic for eval of CA/suspected genetic disorder; clin genetics eval w/med hx, 3 generation pedigree, phys exam; financial hardship precluding appropriate genetic testing | Pts w/isolated feature; acquired disease, pts w/clin dx of specific genetic disease, discharged from clinic | GS | 8/60, 13%: referral to specialists; 3/60, 5%: avoided muscle biopsy; 3/60, 5%: underwent add’l clinical investigation; 1/60, 2%: transition to palliative care | 37/60, 62%: impact on preconception testing/PGD | NR | NR |

| Srivastava et al.28 | 2014 | USA | 11/2011–2/2014 | 78 | DD/ID | Pts presenting to ped neurogenetics clinic at Kennedy Krieger Institute for etiological eval of previously unexplained neurodevel disorders, including DD/ID, CP, and ASD | NR | ES | 5/78, 6%: discontinued meds; 2/78, 3%: added medications; 4/78, 5%: started disease monitoring; 6/78, 8%: investigated systemic involvement; 3/78, 4%: provided info for clin trials | 27/78, 35%: impact on reproductive planning (not otherwise specified) | NR | NR |

| Stark et al.7 | 2016 | Australia | 2/2014–5/2015 | 80 | CA | Infant (≤2 years); multiple CA and dysmorphic features; other features of monogenic disorder (e.g., neurometabolic, renal, eye) | Pts w/CNV responsible for phenotype; previous single-gene testing; single-gene disorder unlikely; disorder caused by known gene unlikely | ES | 9/80, 11%: surveillance for other conditions; 1/80, 1%: stopped surveillance; 2/80, 3%: decision not to undergo muscle biopsy; 1/80, 1%: change of surg approach; 2/80, 3%: rationalized current tx; 3/80, 4%: change of mgmt (NOS); 12/80, 15%: fam members diagnosed through cascade testing w/identification of carrier status/other disorders/risk for disorders (e.g., ACMG v2.0) | 3/80, 4%: used prenatal dx for subsequent preg; 28/80, 35%: now considered “high risk” for future pregnancies | NR | NR |

| Stark et al.23 | 2018 | Australia | 4/2016–9/2017 | 40 | CA | Pts aged 0–18 yrs w/likely monogenic disorder; mult organ syst involved, severe condition w/complexity and/or high acuity | Pts w/CNV responsible for phenotype; previous single-gene testing; single-gene disorder unlikely; secure clinical dx of a monogenic disorder (e.g., Apert, CHARGE syndromes) | ES | Mortality: n = 9, 23%; change in mgmt overall: 14/40, 35%; med. started/adjusted, n = 4; med. stopped, n = 1; surveillance initiated, n = 7; avoidance of tissue biopsy, n = 3; redirection to palliative care, n = 2; provided info for clinical trial, n = 1 | NR | NR | NR |

| Tammimies et al.25 | 2015 | Canada | 2008–2013 | 95 | CA/DD/ID | Pts consecutively referred from 2008 to 2013 from devel ped clinics that perform multidisciplinary team assessments for ASD | NR | ES | 6/95, 6% findings were deemed med actionable | NR | NR | NR |

| Tan et al.43 | 2017 | Australia | 5/2015–11/2015 | 44 | CA | Ambulant children aged 2–18 years; w/ suspected monogenic condition; nondiagnostic SNP microarray | Pts w/suspected disorder that would usually be made by clin assessment; any prior single-gene or panel sequencing test; pts deemed to have novel phenotypes precluding derivation of a reasonable differential dx list | ES | 6/44, 14%: altered clin mgmt; 1/44, 2%: had dx tests canceled | 1/44, 2%: pt‘s parents planned to use PGD | NR | NR |

| Tarailo-Graovac et al.33 | 2016 | Canada | 10/2012–1/2015 | 41 | CA/DD/ID | Consecutively enrolled pts w/confirmed or potential DD/ID disorder; metabolic phenotype of unknown cause after extensive previous metabolic or genetic testing | Confirmed dx of teratogen exposure; congenital infection; autoimmune disorder; pathogenic CNV; withdrawal from study | ES | 11/41, 27%: Initiation/change of med; 3/41, 7%: initiation/change of screening patterns; 2/41, 5%: initiation/change of procedures; 5/41, 12%: initiation/change of dietary modifications | NR | NR | NR |

| Thevenon et al.40 | 2016 | France | NR | 43 | CA/DD/ID | Pts w/absence of a strong dx hypothesis after clin eval; negative dx workup including array-CGH, fragile X screening, targeted testing for single-gene disorders | Pts w/malformative features suggesting syndromic etiology; suspicion of an acquired disorder | ES | 4/43, 9%: change in clin mgmt (in total); coenzyme Q10 supplementation was introduced (20 mg/kg/day) and ketogenic diet has been evoked as the forthcoming therapeutic alternative | 2/43, 5%: pts’ diagnoses enabled two prenatal diagnoses for parents in subsequent pregnancies | NR | NR |

| Thiffault et al.45 | 2018 | USA | 2015–2017 | 80 | CA/DD/ID | NR | NR | ES | 6/80, 8% (total) change of pt mgmt.; 1/80, 1%: care withdrawn; 1/80, 1%: pt transitioned to TSC clinic; 4/80, 5%: Identification of carrier status/other disorders/risk for disorders (e.g., ACMG v2.0) | NR | NR | NR |

| Todd et al.41 | 2015 | Australia | NR | 38 | CA | Dx w/FADS, arthrogryposis, or a severe congenital myopathy | NR | ES | 1/38, 3%: pt & his father had clin mgmt changes, but it does not state what that was | 1/38, 3%: mother of pt w/CHRND variant underwent PGD & subsequently terminated preg w/affected fetus | NR | NR |

| Valencia et al.48 | 2015 | USA | NR | 40 | CA/DD/ID | NR | NR | ES | 9/40, 23%: change in clin mgmt (in total); 8/40, 20%: ended dx odyssey; 2/40, 5%: specific follow-up studies recommended; 3/40, 8%: surveillance recommended; 5/40, 13%: targeted tx/sx tx/new mgmt plan; 1/40, 3%: med concerns for fam members | 14/40, 35%: “informative genetic couns” provided, not otherwise specified | NR | NR |

| van Diemen et al.46 | 2017 | Netherlands | NR | 23 | CA | Age <1 at presentation with 1+ CA and/or severe neuro sx, such as intractable seizures, suggestive of a genetic cause of the disease | Pts w/clear indications for specific syndrome that could be tested by targeted analysis of known genes or structural variations; not critically ill; no consent to rapid targeted genomics test | GS | 5/23, 22%: withdrawal of unsuccessful intensive care tx | 2/23, 9%, pts’ parents changed their mind about NOT having additional children after learning of avail prenatal genetic testing; 1/23, 4% decided to undergo PGD (unclear if performed) | NR | NR |

| Vissers et al.18 | 2017 | Netherlands | 2011–2015; follow-up: min. 6 mos (median: 17 mos) (range: 6–42 mos) after starting ES | 150 | CA/DD/ID | Consecutive pts w/(nonacute) neuro sx of suspected genetic origin | Pts w/well-known, clinically easily recognizable genetic disorders | ES | 1/150, 0.7%: antiepileptic drug changed; comp w/standard genetic testing pathway: 36/150, (24%) pts the dx process would have been limited to ES and no invasive/additional procedures performed | NR | NR | NR |

| Willig et al.22 | 2015 | USA | 2011–2014 | 35 | CA | Parent–child trios enrolled in a research biorepository who had GS and standard dx tests to diagnose monogenic disorders of unknown cause | Infants likely to have disorders assoc w/cytogenetic abnormalities w/positive findings on prior testing | 120-day mortality: w/genetic dx 12/21, 57% vs. no genetic dx 2/14, 14%; p = 0.46; 15/35, 43% (total): change in pt mgmt; 6/15, 40%: palliative care initiated; 3/15, 20%: imaging change; 4/15, 27%: initiation/change of med; 2/15, 13%: initiation/change of diet; 1/15, 7%: specific surg. undertaken b/c of dx result | 4/35, 11%: nonspecified genetic/reproductive couns change | NR | NR | NR |

| Zhu et al.30 | 2015 | USA, Israel | NR | 119 | CA/DD/ID | NR | NR | ES | 2/119 trios, 2%: change of med leading to impr outcomes for patients; 2/119 trios, 2%: initiation/change of dietary mod | NR | NR | NR |

ACMG American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, ASD autism spectrum disorder, assoc associated, avail available, b/c because, biochem biochemical, CA congenital anomalies, CAKUT congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urethral tract, cardio cardiology/cardiologist, CGH (array) comparative genomic hybridization, clin clinical, CMA chromosomal microarray, CNV copy-number variant, comp comparison, couns counseling, CP cerebral palsy, CVS chorionic villus sampling, DD developmental delay, devel developmental, dx diagnostic/diagnosis, ES exome sequencing, eval evaluation, FADS fetal akinesia deformation sequence, fam family, GS genome sequencing, hx history, ICU intensive care unit, ID intellectual disability, impr improved/improvement, IUGR intrauterine growth restriction, lab laboratory, MAGEN a metabolic-neurogenetic multidisciplinary clinic at Wolfson Medical Center in Israel, med medical/medication(s), mgmt management, mod modification(s), mo(s) months, MRI magnetic resonance image, mult multiple, nephr nephrology, neuro neurological, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, NOS not otherwise specified, NR not reported, ophthalm ophthalmologist, PCP primary care provider/physician, ped pediatric, PGD preimplantation genetic diagnosis, PICU pediatric intensive care unity, Preg pregnancy, psych psychology/psychologist, pt(s) patient(s), SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, std standard, surg surgery/surgical, sx symptoms, TSC tuberous sclerosis complex, tx treatment/therapy, VUR vesicoureteral reflux, w/ with, w/o without, yr(s) year(s).

Outcomes of ES/GS for CA or DD/ID

We assessed changes in clinical management and patient outcomes resulting from ES or GS in recognition of the potential impact(s) a genetic diagnosis may have on the patient and their family. Of the 167 included studies, 95% reported a change to patient or family clinical management and most (79%) were case reports or case series with a small number of patients. Table 3 presents an overview of the 36 studies with N ≥ 20 patients and the reported health and clinical outcomes. Several studies provided only representative case examples documenting outcomes of interest.16–19 We summarize the number of studies with N ≥ 20 patients documenting the outcomes of interest and representative examples of reported health outcomes and clinical impacts for each subcategory.

Health outcomes

Mortality and morbidity were reported in three studies. In a case series of patients with CA, a patient in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) with suspected biliary atresia was scheduled for interoperative cholangiogram with reflex to Kasai hepatoportoenterostomy.20 A provisional diagnosis of Alagille syndrome obtained with GS (later confirmed by CMA) was conveyed to doctors urgently, as the patient was in the operating room for induction of general anesthesia for the planned procedure. In patients with Alagille syndrome, the Kasai procedure is associated with increased risk for liver transplant and higher mortality.21 The consensus of an international expert panel was that cancellation of the surgery led to the reduction in mortality risk by 83–94%, compared with the clinical course of a (nonstudy) patient who presented similarly and underwent the surgery the following month. In the same case series, morbidity was avoided in 61% (11/18) of patients who received a diagnosis with rapid GS (results returned in less than 2 weeks), compared with none of the patients who received standard of care,20 suggesting that obtaining a timely diagnosis may result in appropriate management and improved clinical outcomes. In a series of acutely ill infants in the neonatal and pediatric intensive care units (NICU and PICU), Willig et al. reported a higher 120-day mortality rate in 57% (12/21) of patients who received a genetic diagnosis with rapid GS compared with 14% (2/14) of patients who did not, suggesting this population is more medically fragile and may benefit from obtaining results quickly to guide care. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.46).22 A case series of patients undergoing rapid ES in Australia reported a mortality rate of 23% (9/40).23 Generally, however, reported health outcomes were often subjective in nature.

Clinical management outcomes

Baldridge et al. determined that 5% (8/155) of patients had their clinical management directly influenced as a result of ES/GS, including a change in medication, surgical procedures, or referral to specialists.24 Additionally, 54% (84/155) of these patients received additional diagnostic (i.e., molecular, biochemical, imaging) studies following ES, including 12 that were performed after the discovery of a secondary finding (i.e., ACMG59).24 Secondary findings were also reported in a case series of patients with CA/DD/ID.25 Tammimies et al. reported 6% (6/95) of patients had ES findings considered “medically actionable,” including identification of pathogenic variants in FBN1 (Marfan syndrome, familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections), CACNA1S (malignant hyperthermia), and SDHB (hereditary paraganglioma–pheochromocytoma syndrome).25

Medication and dietary management

A change of patient medication, either initiation of a new treatment or halting of an existing one, was specifically reported in 22 studies.8,15–18,20,22,23,26–39 For example, Anazi et al. reported a patient with ID who was homozygous for a truncating pathogenic variant in SLC39A14 that causes a potentially treatable form of hypermanganesemia, who was started on chelation therapy, resulting in improved manganese levels.17 In a case series of patients with presumed neurogenetic disorders and DD/ID from Argentina, 10% (4/40) underwent a trial of new medication following ES, including a trial of L-Dopa in a patient with paraplegia and ID who had pathogenic variants in SPG11 and a trial of acetazolamide and fampridine in a patient with a pathogenic variant in KCNA2.39 In the same study, physicians made recommendations to avoid statins in a patient with a pathogenic variant in DMD and to avoid drugs (unspecified) with mitochondrial toxicity in a patient with a MT-ATP6 pathogenic variant causing DD and epilepsy.39

Alterations to a patient’s existing diet were mentioned in nine studies.8,23,26,27,30,31,33,40,41 In a case series of 43 French patients with dysmorphic features and neurodevelopmental disorders including severe to profound ID, a patient diagnosed with compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in ADCK3 was diagnosed with coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation and a ketogenic diet were introduced following ES results.40 Most studies with a demonstrated change of patient management reported a change in medication and/or dietary management; however, difference in mortality or morbidity following such a change in management was not reported.

Change of procedures or surveillance

Changes to planned procedures (surgery, imaging, and/or diagnostic studies) or surveillance strategies were specified in 19 studies.7,8,11,20,22–24,26–28,32,33,35,37,38,41–44 For example, following ES, 54% (84/155) of patients with CA/DD/ID underwent additional (unspecified) molecular testing, imaging, or biochemical testing.24 In other studies, the ES/GS results led to discontinuation of unnecessary procedures. In a prospective case series of 80 infants with multiple CA and dysmorphic features from Australia, ES resulted in a decision to change surveillance for three patients.7 In one case, echocardiography surveillance for suspected infantile Marfan syndrome was discontinued since the diagnosis was excluded due to the finding of a pathogenic variant in CHRDL1 causing X-linked megalocornea (OMIM 309300). The need for diagnostic tissue biopsy was eliminated for two patients diagnosed with mitochondrial disorders through ES, including combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 11 (OMIM 614922) and mitochondrial short-chain enoyl-CoA hydratase 1 deficiency (OMIM 616277)43 and for an additional three patients with CA/DD/ID in the Illumina iHope program10 and for three patients with CA who received rapid ES results in a case series from Australia.23 In a case series of patients with CA/DD/ID, additional invasive testing/procedures were halted in 2% (2/115) of patients after ES. One patient stopped invasive testing for pulmonary causes of respiratory insufficiency after ES identified a pathogenic variant in KIAA1279 causing Goldberg–Shprintzen megacolon syndrome (OMIM 609460), and another patient stopped testing for a mitochondrial disorder after ES identified a pathogenic variant in SNAP25.26 In another case series of patients with CA, rapid GS yielded a diagnosis of ABCC8-associated familial hyperinsulinism type 1 (OMIM 256450) in a patient with hyperinsulinemia.22 The authors reported that the GS results and clinical presentation suggested the focal form of the disorder. Additional imaging was performed that confirmed focal pancreatic lesions and the patient underwent targeted resection, which avoided development of insulin-dependent diabetes, and resulted in a shorter length of stay in the hospital. The patient remained euglycemic more than one year later.22 Overall, many studies reported a change in planned procedures or surveillance strategies, mainly due to a change in the patient’s diagnosis; however, rarely did the authors present data or a description of any resultant reduction in mortality or morbidity.

Referral to specialists

As a consequence of ES/GS results, patients were referred to specialists in a variety of disciplines for follow-up care. This was reported in six studies.8,11,23,32,41,45 In the NSIGHT randomized controlled trial comparing rapid GS to standard genetic testing in critically ill infants with CA and other disorders at a regional NICU and PICU, 27% (4/15) of patients who underwent rapid GS or who were allowed to crossover to GS had a change in subspecialty consult (unspecified) after receipt of GS results.41 In a case series of 53 patients with CA and neurodevelopmental symptoms, 25% (6/24) of patients who received a diagnosis from ES had referrals to a variety of subspecialists, including nephrology, cardiology, ophthalmology, hematology, audiology, and pulmonology.32 In a case series of 278 infants from intensive care units, initiation of specialist care occurred for 26% (27/102) of patients receiving a diagnosis from ES.8 Of the 41 patients in the Illumina iHope program who received a diagnosis from GS, 20% (8/41) were given referrals to specialists to assess for comorbidities, including neurology, ophthalmology, and audiology.11 Taken together, subspecialty referrals were initiated or changed for ~25% of patients who underwent ES/GS and received a diagnosis.

Redirection of care

Nine studies reported a withdrawal of care or start of palliative care for patients after ES/GS results.8,11,14,20,22,23,45–47 In a case series of patients with CA/DD/ID, care was withdrawn at the family’s request for a patient after GS resulted in a diagnosis of infantile mitochondrial cardiomyopathy with lactic acidosis.45 Among a series of 66 neonatal patients with CA/DD/ID, dysmorphic features, and other clinical symptoms from a clinical laboratory, rapid ES identified a pathogenic variant in SOX10, which is associated with peripheral demyelinating neuropathy, central dysmyelination, or Waardenburg syndrome with or without Hirschsprung disease. In light of the prognosis and expected outcomes for the patient, the family requested ventilator support be withdrawn.47 In a case series of 23 patients with CA and severe neurological defects from the Netherlands, 71% (5/7) had unsuccessful intensive care treatment stopped after receipt of GS results that informed a diagnosis. However, no details about the treatments or the consequences resulting from their cessation were provided.46

In a case series of 35 consecutive patients with CA/DD/ID who were enrolled in a research study assessing rapid GS from a level 4 NICU or PICU at a quaternary children’s hospital in the United States, of the 21 patients who received a diagnosis with GS, 29% (6/21) began palliative care after receiving the diagnosis. Notably, none of the patients without a genetic diagnosis (0 of 14 patients) transitioned to palliative care.22 In another case series, a patient with multiple CA received a diagnosis of Coffin–Siris syndrome following rapid GS and was transitioned to comfort care and subsequently expired.20 In a case series of patients with CA/DD/ID, a patient who received a diagnosis of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis following GS was transitioned to palliative care.11 Overall, withdrawal of care and/or initiation of palliative care following ES/GS was observed in several studies of gravely ill patients.

Clinical trials

Outcomes pertaining to enrollment in or eligibility for clinical trials was specifically reported by six studies.23,24,26,28,32,35 In a large case series of patients with CA by Baldridge et al., 31% (36/115) were enrolled in research studies following ES.24 In a smaller case series of 29 patients in France with CA/DD/ID, two patients (7%) were referred to clinical trials after receiving a diagnosis by ES, including one with a pathogenic variant in the NGLY1 gene (congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ia; OMIM 212065) and another patient with a pathogenic variant in the RNASEH2B gene (Aicardi–Goutieres syndrome 2; OMIM 610181).35 In a case series of 115 patients with CA/DD/ID, ES results prompted physicians to provide information about clinical trial eligibility for a patient with autosomal recessive, early-onset retinitis pigmentosa.26 Though reported by few studies overall, eligibility for and enrollment in clinical trials may present opportunities for potential benefit for patients who have no treatment options.

Family-focused outcomes

Twelve studies reported outcomes following ES/GS that had an impact on family members of the patient, such as cascade genetic testing, referral to specialists, or changes in clinical management resulting from the diagnosis of a previously unknown disorder.7,11,16,19,26,27,31,32,34,41,42,48 In a cohort of 62 families with congenital anomalies of kidney and urinary tract (i.e., CAKUT) who had ES, first-degree relatives of 1 patient were referred for ophthalmological assessment in light of a diagnosis of renal coloboma. The authors reported optic nerve abnormalities were identified in relatives who were PAX2 variant carriers.34 In a case series of 119 patients with DD/ID and neurodevelopmental disorders, a cardiology referral for evaluation of a congenital heart defect was recommended for a patient’s mother after the patient was diagnosed with Renpenning syndrome (OMIM 309500) caused by a pathogenic variant in PQBP1 gene.27 Cascade testing enabled a diagnosis in 12 relatives of the infants in an Australian cohort with multiple CA who had ES results.7 Although the main impact of ES/GS is for the clinical care of the patient, several studies reported impacts to at-risk family members resulting from a diagnosis in the patient. However, subsequent reductions to mortality or morbidity resulting from the identification of these family members and changes in their clinical care were not reported.

Reproductive-focused outcomes

We identified an impact of ES/GS on outcomes related to reproductive planning for families of patients in 20 studies, including the decisions to become pregnant, terminate a pregnancy, use assisted reproductive technologies, use preimplantation genetic diagnosis, use donor sperm/egg, and undergo previously unplanned additional prenatal testing such as chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis.7,8,11,14,16,22,26,28,31,32,35–37,40–44,46,48 ES and GS influenced the decision about having additional children in two studies.37,46 In a case series from the United Kingdom, 1 of 40 parents were considering not having additional children after the patient underwent ES;37 while in a case series from the Netherlands, 9% (2/23) families changed their minds about not having additional children, after learning about the availability of prenatal genetic testing.46

For 95% (20/21) of families who received a result from ES in a German study of 72 patients with CA/DD/ID, the results were important for family planning for either the parents or for the unaffected siblings of patients, and 19% (4/21) of families decided to undergo additional prenatal testing for a subsequent pregnancy based on the patients’ ES results.36 In a case series of patients with CA/DD/ID, Bourchany et al. determined ES enabled reproductive planning in 45% (13/29), and two documented instances of families using ES results to inform prenatal diagnosis in subsequent pregnancies, which confirmed an unaffected fetus in each family.35 In a large case series of patients with CA/DD/ID from the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia, 9% (10/118) of families had genetic counseling, carrier testing, or prenatal diagnostic options following ES results in the proband.16 In another case series of 115 patients with CA/DD/ID from the United States who had ES, three families decided to undergo prenatal genetic diagnosis and one family underwent CVS in subsequent pregnancies following receipt of ES results.26 In an Australian study, a mother of a patient with CA/DD/ID who had a CHRND gene variant underwent prenatal genetic diagnosis in a subsequent pregnancy and terminated the pregnancy when the result showed that the fetus was affected.45 Overall, more than half of larger included studies reported an impact of ES/GS relating to the reproductive planning or decisions of patients’ families, expanding outcomes resulting from ES/GS beyond the patient.

Behavioral/psychosocial outcomes

No included larger studies (N ≥ 20) specifically addressed the impact of ES/GS on behavior and/or psychosocial outcomes for patients or their families, such as depression, anxiety, or changes in interpersonal communication. One study reported a single patient’s family was referred to a support group following ES.32 A case report by Nemirovsky et al. mentioned a family’s anxiety was reduced following the diagnosis of a pathogenic variant in the SHANK3 gene by GS.49 Although obtaining a genetic diagnosis by ES/GS may have personal utility, we did not find evidence that ES/GS influenced behavioral or psychosocial outcomes for CA/DD/ID patients or for their families.

Harms of ES, GS

We defined harms of ES and GS as insurance discrimination; a negative impact on family dynamics or communication; a financial burden of the costs of ES or GS; a financial burden of the costs associated with additional testing, surveillance, medication, or dietary modifications stemming from the results of ES or GS; general negative psychosocial impact to the patient or their family; and reduction or loss of privacy. We identified three studies with n ≥ 20 patients and two studies with n < 20 describing the harms associated with ES and/or GS. Baldridge et al. reported two cases of nonpaternity in their case series of 155 patients that required ethics consultation and altered strategies for pretest counseling.24 Nonpaternity was identified in a single case by van Diemen and colleagues. In that patient, it was necessary to disclose nonpaternity to the family to confirm the diagnosis.46 In a case report by He and colleagues, subsequent to ES, parents declined a potentially therapeutic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for economic reasons.50

DISCUSSION

ES/GS are increasingly employed in the clinical evaluation of patients with a variety of conditions, including CA/DD/ID, as evidenced by the increasing publication rates over the past several years. Our findings demonstrate that ES/GS can influence outcomes for individuals with CA/DD/ID and their family members. Overall, included studies documented a change in clinical management as a result of ES/GS, including change in medications, procedures, or referral to specialists. When considering the types of medical management decisions, more than half of patients experienced a reported clinical impact related to the ES/GS diagnosis. Likewise, more than half of larger included studies reported an impact of ES/GS relating to the reproductive planning or decisions of patients’ families, further expanding the usefulness of ES/GS beyond the patient. However, few studies describe beneficial health outcomes or improved quality of life resulting from ES/GS for patients with CA/DD/ID. Nonetheless, despite little direct evidence that ES/GS improved mortality or ameliorated morbidity, the studies included in this review provide indirect evidence of the clinical and personal utility of ES/GS for patients with CA/DD/ID and their family members.

Though there are many publications describing ES/GS diagnostic yield, we identified relatively few studies documenting outcomes resulting from ES/GS for CA/DD/ID patients or their families. There are several possible reasons for this. First, we explicitly excluded studies that reported only diagnostic yield, as diagnostic yield is already well documented in the literature. Our goal was to assess outcomes resulting from a genetic diagnosis, such as improvement in morbidity or mortality, changes in surveillance or prevention, decisions about medical or surgical interventions, subspecialty referrals, better prognostication, and reproductive counseling. Furthermore, our search did not necessarily encompass all possible measures of utility and thus, this review does not preclude other forms of utility that were not included in the scope of the search strategy. Second, we excluded studies of patients with CA in which the reported age of onset was unstated or diagnosed when greater than 1 year of age. We focused our analysis on studies of patients who present with CA early in life, at a time when a diagnosis made by ES/GS may have the greatest impact for the patient by ending the diagnostic odyssey and for family by providing opportunities for reproductive options in subsequent pregnancies.7,8,14,31 However, patients who present after 1 year of age may also derive benefit from a diagnosis made through ES/GS.

We also found substantial inherent limitations to the included studies. First, most were case reports or small case series where the goal was to make a genetic diagnosis for CA/DD/ID and the reported outcomes of interest were secondary. These study designs are problematic, as they introduce risk of bias and lack of generalizability. However, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which are considered to generate the highest levels of evidence, are unlikely to be performed in this patient population. There was only one RCT (NSIGHT1) that assessed the use of rapid GS, and that study assessed only the rate of diagnosis, and was terminated prematurely due to loss of equipoise and difficulty adhering to randomization to the control group.41 Therefore, observational studies, including case reports and small case series, are important, and often the only form of evidence for patients with rare diseases. Second, among the included studies, there was substantial heterogeneity of patient phenotypes and indications for ES/GS. This translated to very small numbers of patients eligible for similar interventions, hindering robust measurement of the outcomes of interest. Moreover, aside from halting medical management or entering palliative care, outcome measures of morbidity, mortality, or family planning have long time horizons that are difficult to measure. Consequently, the body of evidence supporting or refuting the usefulness of ES/GS for patients with CA/DD/ID is significantly heterogeneous in terms of quality, methods, and reporting, similar to the case for CMA.3

We found that reporting of outcomes we assume are of value to key stakeholders using ES/GS was not uniform or complete.51 For example, we found only two studies demonstrating a reduction in mortality or morbidity resulting from ES/GS. Few studies reported whether the clinical course was improved by medication or diet, or by enrolling in a clinical trial. When a change in diagnostic thinking or clinical management of the patient follows ES/GS, to demonstrate the usefulness and value of the testing, investigators should study the corresponding impact on primary health outcomes where possible, either through comparisons to historical cases or matched controls. Moreover, with the near ubiquity of electronic medical records, this information may be readily available to provide further evidence of the utility of ES/GS. Further, impacts of ES/GS on reproductive-related decisions were generally not well described; many studies only reported vague descriptions or general statements about genetic counseling. We suspect use of ES/GS results informs important family planning decisions more commonly than was reflected in the evidence reviewed. Reproductive decision-making is a valued outcome of genetic testing, and as such, should be systematically measured as an outcome of ES/GS intervention studies.51,52

Future studies of ES/GS should document the impact of test results more routinely and uniformly, and in so doing, make available a more robust body of evidence to support utilization of this critically important technology. To accomplish this, a uniform framework is needed to allow prospective data collection to be standardized and thus, more easily aggregated and compared in meta-analyses. The genetics community should develop a standard set of outcomes for ES/GS, along with corresponding metrics to assess those outcomes to facilitate evidence development. The issue of “what to measure” is somewhat unique for the heterogeneous groups of patients with rare disorders. Defining the outcome measures will allow use of well-established reporting frameworks for studies of ES/GS in rare disease populations, like the PRISMA framework for systematic evidence reviews53 and the CHEERS framework used for economic evaluations.54 Use of frameworks informing data collection and reporting could simultaneously improve the quality of the literature, as most studies we identified were of case reports or small case series with limited assessments when considered specifically in the context of health and clinical outcomes reporting. A recently published scoping review on the use of ES/GS for pediatric patients with phenotypes very similar to the articles we reviewed identified similar limitations within the current body of evidence and appealed for the development of a standard framework for clinical impact data reporting in sequencing studies.12

Conclusion

In summary, we performed a systematic evidence review to characterize the impact of ES/GS in patients with CA/DD/ID on clinical management and health outcomes. We identified one RCT and numerous case series and case reports describing clinical and patient outcomes, for which the overall evidence was limited. However, a change in patient management was observed in nearly all included studies (including case reports), and a substantial number of publications reported a clinical impact on the patient’s family members or an impact on reproductive outcomes. Future studies of ES/GS results for patients with CA/DD/ID should explicitly measure patient and family outcomes resulting from testing to better assess the clinical and personal utility of ES/GS.

Disclosure

S.E.H. received research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals to serve as a site investigator for a prospective registry for hypophosphatasia. D.T.M. received honoraria from Prevention Genetics and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. M.C.S. receives salary (no equity) as a lab director at Washington University School of Medicine, received salary (no equity) as a lab director at HudsonAlpha Institute of Biotechnology (performs clinical whole genome sequencing), and received consulting fees from PierianDx. J.S. received salary from the Partners Healthcare Laboratory for Molecular Medicine and from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Cytogenomics Laboratory. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Correspondence: ACMG (documents@acmg.net)

Disclaimer:

The ACMG has recruited expert panels, chosen for their scientific and clinical expertise, to conduct systematic evidence reviews (SERs) to support the development of clinical practice guidelines. An SER focuses on a specific scientific question and then identifies, analyzes and summarizes the findings of relevant studies. ACMG SERs are provided primarily as educational resources for medical geneticists and other clinicians to help them provide quality medical services. They should not be considered inclusive of all relevant information on the topic reviewed.

Reliance on this SER is completely voluntary and does not necessarily assure a successful medical outcome. In determining the propriety of any specific procedure or test, the clinician should apply his or her own professional judgment to the specific clinical circumstances presented by the individual patient or specimen. Clinicians are encouraged to document the reasons for the use of a particular procedure or test, whether or not it is in conformance with this SER. Clinicians also are advised to take notice of the date this SER was published, and to consider other medical and scientific information that becomes available after that date.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jennifer Malinowski, David T. Miller

These authors contributed equally: Scott E. Hickey, Jun Shen

The Board of Directors of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics approved this systematic evidence review on 27 January 2020.

References

- 1.Manning M, Hudgins L. Array-based technology and recommendations for utilization in medical genetics practice for detection of chromosomal abnormalities. Genet Med. 2010;12:742–745. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f8baad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochstenbach R, van Binsbergen E, Engelen J, et al. Array analysis and karyotyping: workflow consequences based on a retrospective study of 36,325 patients with idiopathic developmental delay in the Netherlands. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, et al. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:749–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan LL, Huang H, Jin JY, et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies a novel mutation (c.333+2T>C) of TNNI3K in a Chinese family with dilated cardiomyopathy and cardiac conduction disease. Gene. 2018;648:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng SSW, Chan KYK, Leung KKP, et al. Experience of chromosomal microarray applied in prenatal and postnatal settings in Hong Kong. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2019;181:196–207. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang W, Kim Y, Han E, et al. Chromosomal microarray analysis as a first-tier clinical diagnostic test in patients with developmental delay/intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, and multiple congenital anomalies: a prospective multicenter study in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 2019;39:299–310. doi: 10.3343/alm.2019.39.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stark Z, Tan TY, Chong B, et al. A prospective evaluation of whole-exome sequencing as a first-tier molecular test in infants with suspected monogenic disorders. Genet Med. 2016;18:1090–1096. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng L, Pammi M, Saronwala A, et al. Use of exome sequencing for infants in intensive care units: ascertainment of severe single-gene disorders and effect on medical management. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:e173438. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark MM, Stark Z, Farnaes L, et al. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of genome and exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in children with suspected genetic diseases. NPJ Genom Med. 2018;3:16. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0053-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nambot S, Thevenon J, Kuentz P, et al. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of rare disorders with congenital anomalies and/or intellectual disability: substantial interest of prospective annual reanalysis. Genet Med. 2018;20:645–654. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scocchia A, Wigby KM, Masser-Frye D, et al. Clinical whole genome sequencing as a first-tier test at a resource-limited dysmorphology clinic in Mexico. NPJ Genom Med. 2019;4:5. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0076-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith HS, Swint JM, Lalani SR, et al. Clinical application of genome and exome sequencing as a diagnostic tool for pediatric patients: a scoping review of the literature. Genet Med. 2019;21:3–16. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain P, Sharma S, Tripathi M. Diagnosis and management of epileptic encephalopathies in children. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2013;2013:501981. doi: 10.1155/2013/501981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.French CE, Delon I, Dolling H, et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals that genetic conditions are frequent in intensively ill children. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:627–636. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05552-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawyer SL, Hartley T, Dyment DA, et al. Utility of whole-exome sequencing for those near the end of the diagnostic odyssey: time to address gaps in care. Clin Genet. 2016;89:275–284. doi: 10.1111/cge.12654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon-Salazar TJ, Silhavy JL, Udpa N, et al. Exome sequencing can improve diagnosis and alter patient management. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:138ra78. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anazi S, Maddirevula S, Fageih E, et al. Clinical genomics expands the morbid genome of intellectual disability and offers a high diagnostic yield. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:615–624. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vissers LELM, van Nimwegen KJM, Schieving JH, et al. A clinical utility study of exome sequencing versus conventional genetic testing in pediatric neurology. Genet Med. 2017;19:1055–1063. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair P, Sabbagh S, Mansour H, et al. Contribution of next generation sequencing in pediatric practice in Lebanon. A study on 213 cases. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2018;6:1041–1052. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farnaes L, Hildreth A, Sweeney NM, et al. Rapid whole-genome sequencing decreases infant morbidity and cost of hospitalization. NPJ Genom Med. 2018;3:10. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0049-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaye AJ, Rand EB, Munoz PS, Spinner NB, Flake AW, Kamath BM. Effect of Kasai procedure on hepatic outcome in Alagille syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:319–321. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181df5fd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willig LK, Petrikin JE, Smith LD, et al. Whole-genome sequencing for identification of Mendelian disorders in critically ill infants: a retrospective analysis of diagnostic and clinical findings. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:377–387. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00139-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stark Z, Lunke S, Brett GR, et al. Meeting the challenges of implementing rapid genomic testing in acute pediatric care. Genet Med. 2018;20:1554–1563. doi: 10.1038/gim.2018.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baldridge D, Heeley J, Vineyard M, et al. The exome clinic and the role of medical genetics expertise in the interpretation of exome sequencing results. Genet Med. 2017;19:1040–1048. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tammimies K, Marshall CR, Walker S, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of chromosomal microarray analysis and whole-exome sequencing in children with autism spectrum disorder. JAMA. 2015;314:895–903. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iglesias A, Anyane-Yeboa K, Wynn J, et al. The usefulness of whole-exome sequencing in routine clinical practice. Genet Med. 2014;16:922–931. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soden SE, Saunders GJ, Willig LK, et al. Effectiveness of exome and genome sequencing guided by acuity of illness for diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:265ra168. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srivastava S, Cohen JS, Vernon H, et al. Clinical whole exome sequencing in child neurology practice. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:473–483. doi: 10.1002/ana.24251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrikin JE, Willig LK, Smith LD, Kingsmore SF. Rapid whole genome sequencing and precision neonatology. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39:623–631. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu X, Petrovski S, Xie P, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in undiagnosed genetic diseases: interpreting 119 trios. Genet Med. 2015;17:774–781. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuperberg M, Lev D, Blumkin L, et al. Utility of whole exome sequencing for genetic diagnosis of previously undiagnosed pediatric neurology patients. J Child Neurol. 2016;31:1534–1539. doi: 10.1177/0883073816664836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolan D, Carlson M. Whole exome sequencing in pediatric neurology patients: clinical implications and estimated cost analysis. J Child Neurol. 2016;31:887–894. doi: 10.1177/0883073815627880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarailo-Graovac M, Shyr C, Ross CJ, et al. Exome sequencing and the management of neurometabolic disorders. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2246–2255. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bekheirnia MR, Bekheirnia N, Bainbridge MN, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in the molecular diagnosis of individuals with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract and identification of a new causative gene. Genet Med. 2017;19:412–420. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourchany A, Thauvin-Robinet C, Lehalle D, et al. Reducing diagnostic turnaround times of exome sequencing for families requiring timely diagnoses. Eur J Med Genet. 2017;60:595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evers C, Staufner C, Graznow M, et al. Impact of clinical exomes in neurodevelopmental and neurometabolic disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2017;121:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller KA, Twigg SR, McGowan SJ, et al. Diagnostic value of exome and whole genome sequencing in craniosynostosis. J Med Genet. 2017;54:260–268. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perucca P, Scheffer IE, Harvey AS, et al. Real-world utility of whole exome sequencing with targeted gene analysis for focal epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2017;131:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cordoba M, Rodriguez-Quiroga SA, Vega PA, et al. Whole exome sequencing in neurogenetic odysseys: An effective, cost- and time-saving diagnostic approach. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thevenon J, Duffourd Y, Masurel-Paulet A, et al. Diagnostic odyssey in severe neurodevelopmental disorders: toward clinical whole-exome sequencing as a first-line diagnostic test. Clin Genet. 2016;89:700–707. doi: 10.1111/cge.12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petrikin JE, Cakici JA, Clark MM, et al. The NSIGHT1-randomized controlled trial: rapid whole-genome sequencing for accelerated etiologic diagnosis in critically ill infants. NPJ Genom Med. 2018;3:6. doi: 10.1038/s41525-018-0045-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Todd EJ, Yau KS, Ong R, et al. Next generation sequencing in a large cohort of patients presenting with neuromuscular disease before or at birth. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:148. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0364-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bick D, Fraser PC, Gutzeit MF, et al. Successful application of whole genome sequencing in a medical genetics clinic. J Pediatr Genet. 2017;6:61–76. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan TY, Dillon OJ, Stark Z, et al. Diagnostic impact and cost-effectiveness of whole-exome sequencing for ambulant children with suspected monogenic conditions. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:855–862. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thiffault I, Farrow E, Zellmer L, et al. Clinical genome sequencing in an unbiased pediatric cohort. Genet Med. 2019;21:303–310. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0075-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Diemen CC, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Bergman KA, et al. Rapid targeted genomics in critically ill newborns. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20162854. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powis Z, Farwell Hagman KD, Speare V, et al. Exome sequencing in neonates: diagnostic rates, characteristics, and time to diagnosis. Genet Med. 2018;20:1468–1471. doi: 10.1038/gim.2018.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valencia CA, Husami A, Holle J, et al. Clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of whole exome sequencing as a diagnostic tool: a pediatric center’s experience. Front Pediatr. 2015;3:67. doi: 10.3389/fped.2015.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nemirovsky SI, Cordoba M, Zaiat JJ, et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals a de novo SHANK3 mutation in familial autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He X, Zou R, Zhang B, You Y, Yang Y, Tian X. Whole Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein gene deletion identified by high throughput sequencing. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:6526–6531. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scheuner MT, Russell MM, Chanfreau-Coffinier C, et al. Stakeholders’ views on the value of outcomes from clinical genetic and genomic interventions. Genet Med. 2019;21:1371–1380. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]