Abstract

Background

The use of appropriate and relevant nurse-sensitive indicators provides an opportunity to demonstrate the unique contributions of nurses to patient outcomes. The aim of this work was to develop relevant metrics to assess the quality of nursing care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where they are scarce.

Main body

We conducted a scoping review using EMBASE, CINAHL and MEDLINE databases of studies published in English focused on quality nursing care and with identified measurement methods. Indicators identified were reviewed by a diverse panel of nursing stakeholders in Kenya to develop a contextually appropriate set of nurse-sensitive indicators for Kenyan hospitals specific to the five major inpatient disciplines. We extracted data on study characteristics, nursing indicators reported, location and the tools used. A total of 23 articles quantifying the quality of nursing care services met the inclusion criteria. All studies identified were from high-income countries. Pooled together, 159 indicators were reported in the reviewed studies with 25 identified as the most commonly reported. Through the stakeholder consultative process, 52 nurse-sensitive indicators were recommended for Kenyan hospitals.

Conclusions

Although nurse-sensitive indicators are increasingly used in high-income countries to improve quality of care, there is a wide heterogeneity in the way indicators are defined and interpreted. Whilst some indicators were regarded as useful by a Kenyan expert panel, contextual differences prompted them to recommend additional new indicators to improve the evaluations of nursing care provision in Kenyan hospitals and potentially similar LMIC settings. Taken forward through implementation, refinement and adaptation, the proposed indicators could be more standardised and may provide a common base to establish national or regional professional learning networks with the common goal of achieving high-quality care through quality improvement and learning.

Keywords: Nurse, Nursing, Nurse-sensitive indicators, Metrics, Quality nursing care and outcome measures

Background

Globally, there is a growing concern about the need for quality health care, with a view that poor-quality care provision is not only wasteful but also ineffective and unethical [1]. Measurement of quality indicators is central to improvement efforts aimed to promote accountability in healthcare and professional practice. Quality indicators arise from the increasing demand for measures of quality across the healthcare continuum ranging from the community to tertiary level [2]. Nurses form the largest component of the health professional workforce and are recognised as essential to the delivery of safe and effective care. Understanding, measuring and reporting the quality of their work is, therefore, critical.

Quality assurance in nursing requires that nurses have the ability to measure their care, to define standards and to change their professional practice [3]. Therefore, measuring what nurses do is important in maintaining standards, supporting nursing management and understanding outcomes and their variation that is linked to nursing. This requires development of sensitive, nursing-specific indicators [4]. Nurse-sensitive indicators (NSIs) have been identified and used by healthcare organisations and researchers to measure how much nurses contribute to patient outcomes [5, 6]. Although there are varied definitions of NSIs, the most comprehensive one defines NSIs as measures of things that are about nursing (structure), about what nurses do (process) or about outcomes that can be linked to structure and process issues. These measures must be quantifiably influenced by nursing personnel, but the relationship between these measures and nursing is not necessarily causal [7].

The use of appropriate and relevant key performance indicators for nursing provides an opportunity to (i) demonstrate the unique contribution nurses make in delivering outcomes for patients and clients [8], (ii) highlight the gaps that might exist in nursing care provision, (iii) inform intervention design for improving nursing care provision and (iv) promote accountability for the care that nurses provide. With a focus on the inpatient setting and the potential use of NSIs for evaluating and improving quality in low- and middle-income countries, our aims were to (i) use a scoping review to identify NSIs reported in the literature and (ii) through a stakeholder-led approach, to adapt and if needed expand NSIs for potential use in Kenyan hospitals, and (iii) to develop a set of indicators with the potential use in wider LMIC contexts to support future evaluations of nursing care provision.

Methods

Review of literature

A scoping review [9, 10] undertaken to identify the literature on metrics for nursing quality of care, nursing care quality and their measurement methods (tools and data collection approaches) was conducted using EMBASE, CINAHL, MEDLINE and Google Scholar databases. The literature search was conducted using the following search terms: nurs* care metrics, nurs* care indicators, nurs* services indicators, nurs* metrics, nurs* care measures, and quality of care or nursing care.

Study selection criteria

We searched for all relevant literature published in the English language (due to time constraints) between 1900 and April 2017. Bibliographic references of retrieved studies were searched for additional articles that reported nursing quality indicators or nursing metrics. All study designs from all settings (LMIC, and high-income countries (HIC)) which reported on nursing care services and had an explanation of the concept of the quality of nursing care, and their measurement methods were included. Studies that reported ambulatory nursing care were excluded since the focus of the study was to develop indicators for the inpatient setting.

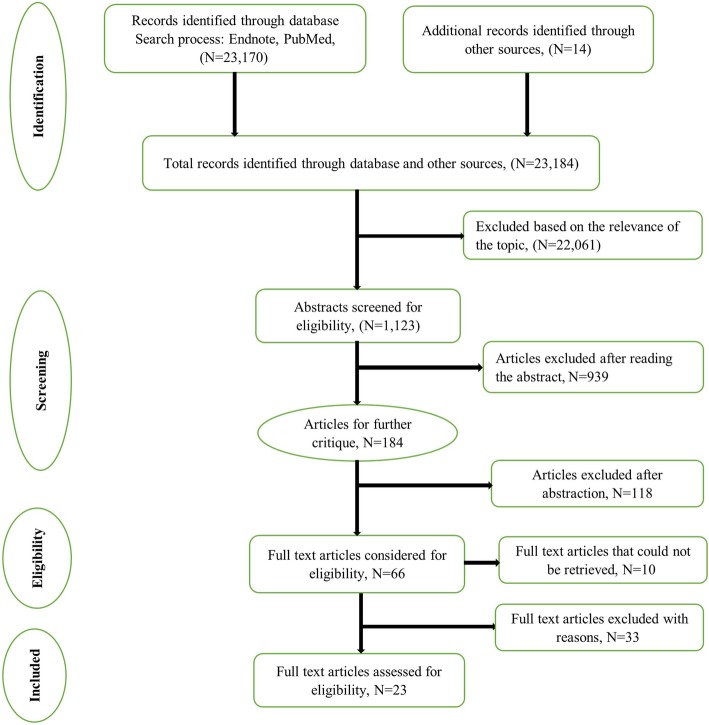

All titles and abstracts of identified articles were screened by two reviewers (DG and MZ) independently, and any disagreements resolved by discussion. Full texts of potentially relevant papers were retrieved, read and subjected to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The authors did not assess the quality of the selected studies as our interest was in capturing a full list of indicators rather than how or how well they have been used. The process and reporting, including the step-wise retrieval, review, appraisal and inclusion into the study of literature (Fig. 1), followed the preferred reporting items for scoping reviews as outlined in the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews statement [11].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart on the literature search process. The PRISMA flow diagram for the selection process of studies and reasons for exclusion

Data extraction and synthesis

Data on study characteristics (e.g. study design, settings, objectives, sample size, discipline/unit), nursing indicators reported, study location and tools used (including availability) were abstracted on a standardised form and are summarised in Additional file 1. The abstraction was completed by one reviewer (MZ); a second reviewer (DG) counter-checked the extracted data. The primary reviewers (DG and MZ) discussed and resolved any differences in perspective that arose during the review to arrive at the final studies for inclusion. Agreement was achieved by consensus.

All of the identified publications mentioned indicators (159) and the studies which included them (across the 23 studies identified) were listed. The data requirements for these indicators were also explored in terms of data source and how to calculate the indicator (numerator/denominator). The indicators were then categorised narratively into three broad overlapping themes (allowing indicators to be in one or more categories) to inform the stakeholder-led process for selection of potential indicators applicable to Kenyan hospitals. The three broad thematic areas identified were (i) commonly reported indicators (identical indicators in four or more studies), (ii) indicators characterised into the respective domains of the Donabedian quality of care model (structure, process and outcome) and (iii) in the opinion of the authors (DG and MZ are both nurses and familiar with the public hospital settings in Kenya), indicators relevant and with potential direct application to Kenya with minor modifications. Indicators reported in the literature linked to other classifications/domains of quality (for instance compassion, safety or patient perspective) were re-categorised into the Donabedian framework based on the authors’ judgement on what domain the indicator best represented.

Stakeholder engagement to adopt/adapt indicators for the Kenyan context

To develop and contextualise a set of NSI to support evaluations of nursing care provision in Kenyan hospitals and wider LMIC settings, we established an expert advisory group (described below) to provide recommendations on what indicators would be contextually appropriate to measure nursing care in an LMIC setting. We presented findings from the scoping review and used the National Quality Forum (NQF) framework [12] on developing indicators for public reporting to guide the advisory panel on the selection of indicators from those identified in the review or develop new ones where necessary. NQF is a consensus-based health care organisation in the United States of America that defines measures or health practices that are the best, evidence-based approaches to improving care [13].

Selection of stakeholders

Drawing on our prior work with a broad neonatal stakeholder group [14, 15], we established an expert advisory group comprising individuals responsible for delivery of nursing care in major public hospitals, neonatal nurse training and nursing services policy in the Ministry of Health and County Governments. We also included major nursing stakeholder groups including the National Nurses Association of Kenya, the Nursing Council of Kenya and development partners (WHO, UNICEF).

The nursing advisory group was aimed at gaining a broad representation of the nursing community rather than a statistically representative group. We constituted panels from the nursing advisory group which met on two occasions for a full day of consultations. In the first meeting, a high-level group (n = 26) involved in policy-making drawn from the nursing directorate at the national level, training and regulatory institutions, and development partners met to review indicators identified through the scoping review with discussions being focused on a pre-identified list of possibly relevant indicators for LMIC selected by the authors. After a plenary session, smaller groups of at least five members, organised so that each group had broad representation in expertise and institutional affiliation, were formed to discuss indicators relevant to inpatient care for the five major inpatient disciplines (surgery, medicine, paediatrics, neonatal care and obstetrics and gynaecology). These discipline-specific groups were tasked with recommending a list of indicators for use in Kenya for the respective disciplines based on the literature in the form of the author’s pre-identified list. On average, each group reviewed 10–15 of the pre-identified indicators. Additionally, group members were allowed to propose new indicators that were not captured in the literature but were deemed appropriate for the Kenyan context based on their experience and expertise which would then be considered by the entire panel. The discussions on indicator selection and prioritisation drew on the guidance from the National Quality Framework (NQF) [12] and focussed on (i) which indicators were relevant and important to these disciplines in representing the quality of nursing care, (ii) acceptability by the nursing profession that the indicator was an important aspect of their work and that its measurement would be a credible as an assessment of their work, (iii) availability of existing data sources that could support evaluations and (iv) where data were not routinely available, whether it would be feasible/realistic to introduce new data elements. After deliberations, each of the discipline-specific groups presented their propositions to the wider advisory group, and consensus on what indicators should finally be proposed was sought through discussion and show of hands.

In the second meeting, the final list of indicators proposed from the initial high-level stakeholder group was presented to a group of 10 front line nurses (two nurses practising in each of the disciplines) for further refinement and prioritisation. This group was not mandated to reject indicators but advised on how to measure these indicators in practice.

The final list of indicators arising from the stakeholder-led process was categorised against the International Patient Safety Goals (IPSG) domains [16] and the Donabedian framework in instances where no suitable domain on the IPSG criteria was identified. The IPSG criteria were developed by the Joint Commission International (JCI) which is a recognised leader in international health care accreditation and focuses on identifying, measuring and sharing best practices in quality and patient safety [17].

Results

Overview of the studies included in this review

Overall, we identified 23 170 articles from database searches and an additional 14 articles from reference lists and Google Scholar. After screening titles and abstracts, 66 articles were considered for full-text review; however, 10 articles were not reviewed because full-text articles were inaccessible to us (n = 6) or they were not available in English (n = 4). Of the 56 full-text articles retrieved, 23 articles met our inclusion criteria. The main reasons for exclusion were that articles reported on ambulatory care indicators, described the process of developing and testing NSIs or were descriptions of how the NQF endorsed indicators might be implemented in practice and their potential impact. The article selection process is presented in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

The reviewed studies included ten that collected primary data, two systematic reviews, three reports, one expert opinion and seven narrative reviews. A detailed description of the studies reviewed is provided in Additional file 1. The primary studies focussed on different settings such as specialist units (inpatient cardiovascular and critical care units, n = 3) and more general settings (acute care settings, medical/surgical units, swing bed units and transitional care, n = 7). The countries in which studies were conducted varied, most (n = 10) were conducted in the United States of America, followed by Europe (n = 6), Asia (n = 5) and Australia (n = 2). Within a single study, the minimum number of indicators was 6, the maximum was 44 and the median was 11 (IQR 7–17). Study type, setting, number of indicators reported and country where the study was done are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the studies included in this review

| Author | Title | Sample size | Aim and setting | Study method | Indicator domain (number) | Study location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kunaviktikul et al. 2005 |

Development of indicators to assess the quality of nursing care in Thailand | Not specified | General clinical nursing | Descriptive observational (FGDs observation sheets, record retrieval forms) | 9 indicators; Structure (2), process (2), outcome (5) | Thailand (Asia) |

|

McCance et al. 2012 |

Identifying key performance indicators for nursing and midwifery care using a consensus approach | 130 | General nursing and midwifery | Consensus (collaborative problem solving) method | 6 process indicators | Ireland (Europe) |

|

Langemo et al. 2002 |

Nursing quality outcome indicators: The North Dakota Study | 217 nurses; 924 patients | Medical and surgical units, intensive care units, transitional care, and swing bed units | Expert/questionnaire | 11 indicators: structure (3), process (3), outcome (5) | North Dakota (United States of America) |

|

Pazargadi et al. 2008 |

Proposing indicators for the development of nursing care quality in Iran | 161 nurses | General clinical nursing | Descriptive-exploratory | 20 indicators: structure (10), process (5), outcome (5) | Iran (Asia) |

|

La Sala et al. 2017 |

The quality of nursing in intensive care: a development of a rating scale | 43 experts | Intensive care unit | Literature review and panel of experts | 21 process indicators. | Italy (Europe) |

|

Fugaça et al. 2015 |

Use of balanced indicators as a management tool in nursing | 200 medical records | Intensive care unit | Case study | 14 indicators: structure (1), process (7), outcome (6) | Brazil (United States of America) |

|

Burston et al. 2013 |

Nurse-sensitive indicators suitable to reflect nursing care quality: a review and discussion of issues | 40 studies | General nursing | Review | 44 outcome indicators | Australia |

| Foulkes et al. 2011 | Nursing metrics: measuring quality in patient care | Not specified | General nursing | Expert opinion | 10 indicators: safety (5), effectiveness (3), nurses compassion (2) | United Kingdom (Europe) |

|

Chen et al. 2016 |

Using the Delphi method to develop nurse-sensitive quality indicators for the NICU |

41 experts | Neonatal intensive care units | Modified Delphi technique | 11indicators: structural (1), process (2), outcomes (8) | China |

|

Seaman et al. 2016 |

Abstracting ICU nursing care quality data from the electronic health Record |

1 440 case records | Intensive care unit | Single-blind, randomised crossover cluster (stepped wage) design | 6 indicators | Pennsylvania (United States of America) |

|

Martha et al. 2006 |

The nightingale metrics | Not specified | General nursing | Focused group discussion | Inpatient cardiology unit (4), PICU (7), CICU (6), NICU (8) | Boston (United States of America) |

|

Twigg et al. 2015 |

Foundation of nurse-sensitive outcome indicator suite for monitoring public patient safety in Western Australia | 259 463 patient records | Medical and surgical units | A review of literature and piloting of indicators on an EHR | 8 outcome indicators | Australia |

|

Maben et al. 2012 |

High quality metrics for nursing. | 18 experts | General nursing | Taskforce review | 34 indicators: safety (9), effectiveness (5), patient experience (10), workforce (5), staff experience (5) | United Kingdom (Europe) |

|

Griffiths et al. 2008 |

State of the art metrics for nursing: a rapid appraisal | Not applicable | General nursing | Review | 18 indicators: safety (7), effectiveness (8), compassion (3) | United Kingdom (Europe) |

|

Koy et al. 2016 |

The quantitative measurement of nursing care quality: a systematic review of available instruments | 18 tools | General nursing | Systematic review | Nurses’ perspectives (11), patients’ perspectives (5). Categories and subcategories of nurse-patient perspectives | Cambodia (Asia) |

|

McCance et al. 2009 |

Using the caring dimensions inventory as an indicator of person-centred nursing. | 107 patients; 122 nurses | Medical and surgical, ICU, operating room, sexual health clinic, older people rehabilitation and paediatric infectious disease wards | Quasi-experimental |

40 indicators: nurses’ perspectives (19), patients’ perspective (21) Both nurses and patients (6) |

United Kingdom (Europe) |

| Montalvo et al. 2007 | The national database of nursing quality indicators | General nursing | Report | 14 indicators: structural (4), process (1), outcome (4), outcome/process (4) | United States of America | |

|

Zhang et al. 2016 |

Assessing nursing quality in paediatric intensive care units; a cross sectional study in China. | 1 385 patients and 274 PICU nurses. | Paediatric intensive care units | Descriptive, cross-sectional | 15 indicators: structural (5), process (3), outcome (7) | China |

|

Riehle et al. 2007 |

Specifying and standardizing performance measures for use at a national level; implications for nurse-sensitive care performance measures. | General nursing | Report | 35 outcome indicators | United States of America | |

|

Lacey et al. 2006 |

Developing measures of paediatric nursing quality | 10 acute care hospitals | Paediatric units | Review of literature, panel of experts and pilot study | 6 outcome indicators | United States of America |

|

Stratton et al. 2008 |

Paediatric | 34 patient care units. | Paediatric units | Descriptive, Correlational, linear mixed model. | 9 indicators | United States of America |

|

St Pierre et al. 2006 |

Staff nurses’ use of report card data for quality improvement | General nursing | Report | 14 indicators | United States of America | |

|

Lacey et al. 2009 |

Nursing; key to quality improvement | General nursing | Review | 15 indicators: patients centred (8), nursing-centred (3), system-centred (4) | United States of America |

CICU cardiac intensive care unit, FGD focused group discussion, HER health electronic records, KPI key performance indicator, NHS national health service, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, PICU paediatric intensive care unit, SOP standard operating procedure

Different authors had different approaches for classifying nurse-sensitive indicators. In a study conducted by Foulkes aiming at enhancing the understanding of nursing metrics in clinical practice in the United Kingdom, nursing indicators were categorised into safety, effectiveness and compassion in nursing care [18]. The High-Quality Care Metrics for Nursing report categorised the quality outcome into safety, effectiveness and experience of the care provision (both nurses and patients) categories [19]. In the review by Koy and colleagues, indicators were classified into nurse perspectives, patient perspectives and nurse-patient perspectives based on who’s perception of quality the indicator was measuring [20]. McCance et al. also reported patient and nurse perceptions of caring based on the patient-centred nursing framework [8]. The most commonly adopted approach by authors was the empirical framework for quality of care assessment of health systems by Donabedian that focuses on the structure, process and outcome domains [21]. There were variations in the domains reported with studies reporting indicators in all three [22–24] or one of three domains without explicitly mentioning which domain these indicators belonged to [6, 25–27]. A summary of the indicators reviewed and the domain they were categorised into as per the Donabedian quality care model is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Nurse-sensitive indicators identified from the literature and classified as per the Donabedian quality framework (indicators have been extracted as reported in the literature, and indicators with similar definitions or measuring the same construct are included)

| Outcome | |

| Failure to rescue | Pain presence |

| Postoperative respiratory failure | Patient satisfaction with pain management |

| Patient complaints | Pain management/controlled |

| Patient satisfaction with educational information | Nurse staff satisfaction |

| Patient satisfaction with nursing care | Physical well-being |

| Patient satisfaction with overall care | Psychological wellbeing |

| Patients’ confidence in knowledge and skills of the nurse | Iatrogenic lung collapse |

| Patient’s sense of safety whilst under the care of the nurse | Atelectasis |

| aPatient involvement in decisions about their nursing care | Fluid overload |

| Respect from the nurse for patient’s preference and choice | Falls |

| Nurse’s support to patients to care for themselves, where appropriate | Injuries to patient |

| Nurse understanding of what is important to the patient | Patient’s falls with injuries in the hospital |

| Patient satisfaction with nurse communication | Staff injuries on the job |

| Patients experience of care | Knowledge, behaviour, status change scores |

| Patient/family complaints satisfaction | Physical and mental health change scores |

| Parent/family complaint rate | Follow-up rate to allergy risks |

| Patient judgement of hospital quality | Adverse drug reaction rate |

| Central line catheter-associated bloodstream infection | Total of prescription mistakes |

| Hospital-acquired pneumonia | Total of transfusion reaction |

| Respiratory tract infection | Upper GI bleeding |

| Nosocomial infection | Mortality |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) | Shock/cardiac arrest |

| Wounds dressed | Deep vein thrombosis |

| Intravenous/vascular access infection | CNS complications |

| Thrombophlebitis | Deterioration |

| Vascular access infiltration | Complications |

| Vascular access thrombosis | Health status |

| Peripheral venous extravasation | Symptom management index |

| Hospital-acquired urinary tract infection | Symptom resolution |

| Urinary catheter-associated UTI | Metabolic derangement |

| Wound infection | Functional status |

| Surgical wound infection | Rate of accidental endotracheal extubation |

| Sepsis | Retinopathy of the preterm child (ROP) |

| Intravascular infiltration due to IV therapy | Heavy sedation |

| Gastrointestinal infection rate | Average hospital length of stay |

| Pressure ulcer prevalence | Vaccination |

| Psychiatric physical/sexual assault rate | |

| Process | |

| Wound care | Smoking cessation counselling |

| Skin integrity/pressure ulcer prevention | Smoking cessation counselling for heart failure |

| Decubitus prevention care | Smoking cessation counselling for pneumonia |

| The risk factors for pressure sores have been documented | Smoking cessation counselling for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) |

| Pain assessment with scale and recorded | Nursing care supervision |

| Chest-abdomen drain changed as by the protocol | Assessment and record reflex presence (e.g. ocular) |

| Chest-abdomen drain insertion area dressed as by guideline | Proper patient positioning in bed |

| Mechanical ventilation has been replaced according to protocols | Monitor alarms properly set |

| Body temperature values have been updated in the last 24 h | ABG result 1 hour after endotracheal tube removal is available |

| The pulse oximetry has been monitored and recorded | Endotracheal suctioning performed as per prescription and recorded |

| The ECG and vital signs have been recorded on admission | Hand washing and hand hygiene |

| Measuring of patient observations (vital signs) | Documentation of results |

| Fluid intake and output have recorded | Number of patient transfers |

| Patient washing once a day and recorded | Double-checking of all medication by two nurses |

| Patient mouth washing as by ward procedure and recorded | Weight documentation daily |

| aAssisting a patient with activities of daily living | Relative/parent notification of patients transfer |

| aInstructing patient about self-care | Unplanned admission |

| aBeing honest with a patient | Interprofessional relations |

| aKeeping relatives informed about a patient | Emergency care |

| aProviding privacy for a patient | Discharge and case management |

| aGetting to know the patient as a person | Appraisal and induction |

| aGiving reassurances about a clinical procedure | Nurses’ compliance in filling of medical records |

| Information and involvement of family into the end of life care by nurses | aListening to a patient |

| Physical and chemical restraint | aExplaining a clinical procedure to a patient |

| aMedication errors | aBeing with a patient during a clinical procedure |

| Antithrombotic therapy given and recorded at the correct time | aConsulting with a doctor |

| aReporting a patient’s condition to a senior nurse | aObserving the effects of medication on a patient |

| Structure | |

| Satisfaction questionnaire about work periodically administered to nurses | level of education and work experiences of nurse managers |

| Total nursing care hours provided per patient day | Nursing continuing education |

| Skill mix (mix of RNs, LPNS and unlicensed staff) | In-service education hours for nursing staff per year |

| Number of nurses per patient | Educational materials for nurses in the hospital (library, internet, etc.) |

| Working hours of nursing staff | Organisational goal setting |

| Proportion of nurses working more than 3 years (nurses experience) | Nursing job description |

| Nurse bed care ratio | Organisational budgeting for patient safety |

| Voluntary nurse staff turnover rates | Patient waiting time for nursing care |

| Patient to nurse ratio | Nursing care standards in hospitals |

| Nurse vacancy rate | Safety environment for nurses in hospital |

| Overtime | Practice environment scale-Nursing Work Index |

| Understaffing as compared to the organisation’s plan | Noise |

| On-call or per diem use | Emergency equipment/drugs available |

| Sick time | Total volume of laundry per patient |

| Agency staff use | Visitation policy |

| Staffing level of education | Absenteeism |

aIndicators used to measure nursing quality from a nurse or patient perspective

Indicators relevant for LMICS

Of the 159 indicators identified from the literature, the authors identified 70 indicators relevant to LMIC settings based on their understanding and experience in this context. These were then presented to the stakeholder group for consideration for use in LMIC hospitals. Of these, 31 indicators were adopted by stakeholders through the consensus process. These indicators were revised and clarified to take into account the Kenyan context. An additional 34 indicators were proposed by the stakeholder group based on the need and priority to monitor specific aspects of nursing care in LMIC. Of these, 21 indicators were adopted after deliberation and based on panel consensus. In total, 52 NSIs potentially relevant to LMIC settings were identified. This included 14 of the 25 commonly reported indicators (reported in at least four or more studies) presented in Additional file 2. A detailed description of the indicators adapted from existing indicators (literature), those recommended as additional indicators and the proposed methods for measuring the indicators as suggested by the stakeholder group is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

LMIC relevant Nursing sensitive indicators aligned with International Patient Safety Goals

| International patient safety goals domain | Indicator definition | Source of indicator | Measurement approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identify patients correctly | |||

| Proportion of patients with name tags | Literature (IPSG) | Structure | |

| Improve effective communication | |||

| Proportion of patients who have a complete assessment (history, head to toe examination, vital signs, weight/height, plan of care) at admission | Literature | Process | |

| Proportion of patients who have discharge instructions (follow-up care, education, return date) | Literature | Process | |

| Proportion of patients with appropriate vital signs monitoring as per patient acuity documented | Literature | Process | |

| Proportion of patients who received at least one session of counselling or communication in 24 hours | Literature | Process | |

| Proportion of patients with assessment and planning of care done at least once in 24hours | Literature | Process | |

| Proportion of patients with ward round recommendations documented in the cardex | Stakeholders | Process | |

| Proportion of patients with surgeons’ instructions transferred to the cardex and with completely filled postoperative forms | Stakeholders | Process | |

| Availability of basic nursing forms/charts | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Adverse effects reporting system in place to reporting | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Improve the safety of high-alert medications | |||

| Record of daily stock monitoring/handover and safety of drugs classified under the Dangerous Drugs Act | Stakeholders | Structure | |

| Proportion of blood transfusions monitored as per blood transfusion guidelines | Literature | Process | |

| Proportion of documented blood transfusions reactions | Literature | Outcome | |

| Proportion of patients on anti-coagulation therapy with dose, drug and food interactions, and appropriate nursing care documented | Literature (NPSG) | Process | |

| Proportion of patients on drugs with a narrow therapeutic range that are flagged | Literature (NPSG) | Process | |

| Ensure correct site, procedure, patient for surgery | |||

| Proportion of patients scheduled for surgery with correctly and completely filled preoperative forms/checklist | Stakeholders | Process | |

| Proportion of patients with the status of the patient, surgical procedure and surgical site, documented in the cardex | Literature (IPSG) | Process | |

| Proportion of patients with filed consent form before surgery | Stakeholders | Process | |

| Proportion of patient identifiers before surgery (name tags/other identifying measures) | Literature (IPSG) | Process | |

| Proportion of patients with pre-marked sites for procedures that require marking of the incision or insertion site. | Literature (IPSG) | Process | |

| Reduce risk of HCA infections | |||

| Proportion of surgical patients with post-operative surgical wound infection | Literature | Outcome | |

| Proportion of patients on intravenous fluids/treatment whose cannula site was checked and documented (state of cannula site- swollen, SSI, soiled) | Literature | Outcome | |

| Proportion of patients on intravenous fluids/treatment whose cannula site was checked and documented vascular access infiltration | Literature | Outcome | |

| Proportion of patients requiring wound cleaning with wound cleaned and wound dehiscence (wound characterization-burst wound, septic, granulating, necrotic), exudate and pain documented | Literature | Process | |

| Proportion of newborns aged <5 days and born within the hospital who develop septic cords | Stakeholders | Outcome | |

| Proportion of newborns on phototherapy with documentation of eyecare done, eyes checked for damages and eye pad changed once in 24 hours | Stakeholders | Process | |

| Proportion of patients with UTI in non-genito urinary infection with documentation for input-output monitoring | Literature | Outcome | |

| Proportion of patients who develop pressure ulcers while in the ward | Literature | Outcome | |

| Proportion of patients with basic activities of daily living (ADL) done. | Literature | Process | |

| Compliance with hand hygiene guidelines based on established goals | Literature | Process | |

| Patient education on infection prevention practices | Stakeholders | Process | |

| Availability of hand hygiene guidelines/training/reminders | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Availability and easily accessible clean toilets | Stakeholders | Structure | |

| Availability of Waste segregation (3 bins and sharp boxes) | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Needle, sharp box more than 3/4 full, or any used needles/sharps outside the box | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Bandages/infectious waste lying uncovered | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Clean running water (piped, bucket with tap, or pour pitcher) | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Functioning hand hygiene stations (that is, alcohol-based hand rub solution or soap and water with a basin/pan and clean single-use towels) | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Storage space for sterile and high-level disinfected items (either a room with limited access or a cabinet that can be closed) | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Reduce risk of patient harms resulting from falls | |||

| Proportion of patients with risk of falling who have harm reduction measures | Literature | Process | |

| Use of physical restraint | Literature | Process | |

| Proportion of patient falls with injuries | Literature | Process | |

| Additional indicators that don’t fall in the IPSG criteria | |||

| Other safety related indicator | |||

| Proportion of patients at risk of DVT (immobile, obese, on total nursing care etc) who are assessed for DVT at least once in 24 hours | Literature | Process | |

| Proportion of diabetic and critically patients with blood sugar monitoring | Stakeholders | Process | |

| Proportion of diabetic patients with the following documented: type of feed, medication, frequency, intervention, sugar levels, time of last feed to help interpret the result) | Stakeholders | Process | |

| Structure indicators | |||

| Patient to nurse ratio | Literature | Structure | |

| Nurse skill mix (by education level) | Literature | Structure | |

| Staff wearing name tags and on uniform | Stakeholders (HFA) | Structure | |

| Outcome indicators | |||

| Patient satisfaction with overall care | Literature | Outcome | |

| Patient satisfaction with nursing care | Literature | Outcome | |

| Proportion of patients who died | Literature | Outcome | |

| Average length of stay (by illness acute vs chronic) | Literature | Outcome | |

Literature - Indicator identified from the systematic adopted for LMIC/Kenyan context; Stakeholder - Indicator not defined in literature but stakeholders felt this was a priority/important area to measure; IPSG/NPSG - Indicator has been defined under either of these criteria; Stakeholder (HFA) - indicator already exists in the Joint Health Facility Assessment (HFA) indicator set developed through a stakeholder process

UTI Urinary tract infection, DVT Deep venous thrombosis, HCA Health care acquired

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify from the literature ‘nurse-sensitive indicators’ (NSIs) and, use a stakeholder-led approach, to develop and contextualise potential indicators to support evaluations of nursing care provision in Kenyan hospitals and potentially similar LMIC settings. Although there were several studies reporting NSIs, there were inconsistencies in the terminologies/definitions used to describe nursing quality indicators including nurse-sensitive indicators, nursing key performance indicators, nurse-sensitive quality indicators and nursing metrics [2, 5, 6, 20, 28]. In addition, definitions used for indicators varied by tool and data source despite the indicators aiming at assessing the same practice or outcome. For instance, nosocomial infections are considered in the aggregate in some studies whilst others described them by the system affected or resulting diseases such as urinary tract infections, pneumonia and upper respiratory infections. For example, some studies reported pneumonia and ventilator-acquired pneumonia as separate indicators (Table 4) [6, 29]. Consequently, there is considerable overlap in measurement approaches and limited standardisation across indicators undermining comparison between organisations or hospitals. Given the costs of measurement and the limited resources in LMICs, it will be important that a consistent and standard approach to indicator definition and measurement is developed to support the evaluation of nursing care in these settings.

Table 4.

Indicators with similar definitions or measuring similar construct

| Broad indicator definition | Indicators as defined in the literature |

|---|---|

| Failure to rescue | Failure to rescue |

| Postoperative respiratory failure | |

| Patient satisfaction | Patient complaints |

| Patient satisfaction with educational information | |

| Patient satisfaction with nursing care | |

| Patient satisfaction with overall care | |

| Patients’ confidence in knowledge and skills of the nurse | |

| Patient’s sense of safety whilst under the care of the nurse | |

| Patient involvement in decisions made about their nursing care | |

| Respect from the nurse for patient’s preference and choice | |

| Nurse’s support to patients to care for themselves, where appropriate | |

| Nurse understanding of what is important to the patient | |

| Patient satisfaction with nurse communication | |

| Patients experience of care | |

| Patient/family complaints satisfaction | |

| Parent/family complaint rate | |

| Patient judgement of hospital quality | |

| Hospital-acquired infection | Central line catheter-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) |

| Hospital-acquired pneumonia | |

| Respiratory tract infection | |

| Nosocomial infection | |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) | |

| Wounds dressed | |

| Intravenous/vascular access infection | |

| Thrombophlebitis | |

| Vascular access infiltration | |

| Vascular access thrombosis | |

| Peripheral venous extravasation | |

| Hospital-acquired urinary tract infection | |

| Urinary catheter-associated UTI | |

| Wound infection | |

| Surgical wound infection | |

| Sepsis | |

| Intravascular infiltration due to IV therapy | |

| Gastrointestinal infection rate | |

| Wound care | |

| Pressure ulcer | Pressure ulcer prevalence |

| Skin integrity/pressure ulcer prevention | |

| Decubitus prevention care | |

| The risk factors for pressure sores have been documented | |

| Pain management | Pain presence |

| Patient satisfaction with pain management | |

| Pain management/controlled | |

| Pain assessment with scale and recorded | |

| Job satisfaction and health worker well-being | Nurse staff satisfaction |

| Physical well-being | |

| Psychological wellbeing | |

| Satisfaction questionnaire about work periodically administered to nurses | |

| Staffing and skill mix | Total nursing care hours provided per patient day |

| Skill mix (mix of RNs, LPNS and unlicensed staff) | |

| Number of nurses per patient | |

| Working hours of nursing staff | |

| Proportion of nurses working more than 3 years (nurses experience) | |

| Nurse bed care ratio | |

| Voluntary nurse staff turnover rates | |

| Patient to nurse ratio | |

| Nurse vacancy rate | |

| Overtime | |

| Understaffing as compared to organisation’s plan | |

| On-call or per diem use | |

| Sick time | |

| Agency staff use | |

| Staffing level of education | |

| Level of education and work experiences of nurse managers | |

| Absenteeism | |

| Nursing education | Nursing continuing education |

| In-service education hours for nursing staff per year | |

| Educational materials for nurses in the hospital (library, internet, etc.) | |

| Respiratory support or failure | Iatrogenic lung collapse |

| Atelectasis | |

| Chest-abdomen drain changed as by the protocol | |

| Chest-abdomen drain insertion area dressed as by guideline | |

| Mechanical ventilation has been replaced according to protocols | |

| Vital signs monitoring | Body temperature values have been updated in the last 24 h |

| The pulse oximetry has been monitored and recorded | |

| The ECG and vital signs have been recorded on admission | |

| Measuring of patient observations (vital signs) | |

| Fluid input output monitoring | Fluid overload |

| Fluid intake and output have recorded | |

| Activities of daily living | Patient washing once a day and recorded |

| Patient mouth washing as by ward procedure and recorded | |

| Assisting a patient with activities of daily living | |

| Self-care | |

| Nursing support and communication to patients | Being honest with a patient |

| Keeping relatives informed about a patient | |

| Providing privacy for a patient | |

| Getting to know the patient as a person | |

| Giving reassurances about a clinical procedure | |

| Information and involvement of family into the end of life care by nurses | |

| Falls | Falls |

| Injuries to patient | |

| Patient’s falls with injuries in the hospital | |

| Staff injuries on the job | |

| Physical and chemical restraint | |

| Medical/nursing errors | Adverse drug reaction rate |

| Total of prescription mistakes | |

| Total of transfusion reaction | |

| Medication errors | |

| Counselling | Smoking cessation counselling |

| Smoking cessation counselling for heart failure | |

| Smoking cessation counselling for pneumonia | |

| Smoking cessation counselling for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) |

Using a stakeholder-driven approach, indicators identified from the literature were reviewed for relevance to a LMIC setting and where necessary initially adapted by discipline-specific groups (surgery, medicine, paediatrics, neonatal care and obstetrics and gynaecology). Of the 159 indicators identified, 70 were considered by researchers familiar with the local context and with quality measurement as potentially relevant to LMIC hospital settings. Of these, 31 were selected (and often adapted) by local stakeholders as likely to be useful for the Kenyan context. The reasons why indicators were excluded spanned different case-mix of patients and hospital settings including the availability of technology and infrastructure in HICs that were often lacking in LMICs. An additional 21 indicators that were not identified in the literature were recommended by stakeholders to measure aspects of nursing care provision that were considered a priority for the Kenyan context. These additional indicators spanned the domains of structure assessment (e.g. availability of resources to support infection prevention and control activities/practices) and process (e.g. monitoring of phototherapy, communication and coordination of care through documented doctor’s ward rounds and consenting for surgical procedures). Our final set of indicators (n = 52) was classified based on the International Patient Safety Goals (IPSG) framework [16] (Table 3) and spanned all the domains of patient identification (n = 1); effective communication (n = 9); safety of high-alert medication (n = 5); correct site, procedure and patient for surgery (n = 5); risk of health care-acquired infections (n = 19); and patient harms resulting from falls (n = 3). Developing measurements of the work done by nurses and a link to patient safety may be important in helping us understand the consequences of workforce shortages, and such measures could be helpful in accreditation programmes emerging in LMICs [30–32] whilst drawing lessons from global programmes such as the Joint Commission International (JCI) [33].

Progress has been made in defining, refining and testing NSIs in HICs with the development of nursing networks that use NSIs for quality improvement. Examples of these include the adoption and widespread use of the American Nurses Association National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI) in evaluating the nursing quality of care [34] and the creation of minimum datasets for nursing quality indicators [35], but all these are limited to HICs. Exploring the commonly reported NSIs in HIC settings for transferability to LMIC with the premise that these are the most robust indicators based on their prevalent use, only 14 out of the 25 commonly reported indicators were adopted by stakeholders (Additional file 2). This suggests varying contexts and needs that should be considered when adapting recommendations from other settings. Therefore, approaches and progress made provide important lessons for LMICs as they consider indicators for adoption and operationalisation to avoid pitfalls that might have been experienced by HICs during the processes of setting up these systems. We hope by developing NSIs for a LMIC setting and using lessons on their implementation from HIC will help demonstrate the value, importance and broader contribution of nursing to high quality care both at local and wider levels whilst exploring what might constitute a minimum data set that allows quality monitoring and risk adjustment.

Nurses, the largest component of the health professional workforce, are essential to the delivery of safe and effective care as there are very few interventions (both clinical and nurse initiated) that occur without nursing involvement. Whilst nurses comprise the largest workforce and are considered the ‘glue’ that holds the health care system together, they are too often undervalued and their contribution to the quality of care agenda underestimated [36]. This is probably because most of what they do is rarely measured, particularly in the LMIC health care settings where most measures of quality of care provided focus almost exclusively on more medical aspects of care [37, 38]. Therefore, measuring what nurses do and the quality of the care they deliver is essential in demonstrating the value of nurses and their work in promoting safety. These measurements will also be useful in highlighting the implications of workforce shortages and identifying opportunities for improving care whilst building improvement networks to promote nurse-led initiatives.

Our proposed set of indicators needs to be considered in light of the following limitations. Firstly, our review methods and stakeholder engagement differed from the more formal structured approaches of undertaking a systematic review and Delphi approach to indicator development. However, the process of developing and selection of indicators involved a wide range of stakeholders and were agreed upon through a consensus-based approach hence providing face validity. Although our final list of indicators (n = 52) have not formally been validated with a wider stakeholder group, we feel it provides an initial indicator set for testing in future studies of nursing care provision. We recognise that some indicators might be considered more critical than others such as those linked to patient outcomes (e.g. mortality) or due to their overall contribution to quality care. We adopted a simple approach giving each indicator equal weights that was deemed easiest for the diverse expert group to understand. The aim was to generate an initial set of indicators that can be further evaluated with the potential for introducing weighting based on further work. As such, this list is only indicative of what aspects of nursing should be measured and does not take into account the relative importance of various indicators. Secondly, anecdotal evidence and from the literature [39–42] suggests that documentation of nursing is often fragmented, completed on several forms, sometimes in triplicate, and often completed in free text. This may undermine the application of the proposed indicators that are based on document review. As such, piloting of the proposed indicators in routine practice to evaluate their feasibility, reliability and construct validity will be important. To monitor and track the proposed NSIs may require better tools to support nursing care documentation, for instance, structured nursing notes. Similar efforts of co-designing structured nursing forms in Uganda and the United Kingdom have shown improvements in communication between nurses and other professionals whilst reducing time spent on documentation [43, 44].

Conclusion

Our proposed nurse-sensitive indicators informed by the literature and developed with stakeholders provide an opportunity for identifying gaps, developing targeted interventions for investment and improving care and mechanisms to support governance and accountability mechanisms that improve quality in LMIC health systems. The proposed NSIs for Kenya contribute to the dearth of information globally on NSI for monitoring quality of nursing care, particularly for LMICs. Further work on their validation through implementation, refinement and adaptation is required to generate a widely agreed set of standardised indicators. The latter provides an opportunity for LMICs to establish or join national or regional professional learning networks such as those in HICs [34, 45] or that are emerging in LMICs [46] that are showing success in achieving high-quality care through quality improvement and learning. Finally, measures of nursing quality might strengthen the voice of nurses in policy and practice and their position in planning and management roles where the nursing voice is often lacking.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Odesa Omayo, Joan Basweti, Josephine Aritho, Ann Kawira, Cathering Ngugi, Magdalene Njeri, Sphinicah Mogoti, Benson Nyankuru, Susan Njambi, Monica Kangethe, Betty Lessonet and Mary Khanyumbi, nurses who contributed enormously in the review and refining of the indicators identified from the stakeholder workshops. We are grateful for the ongoing support and intellectual contributions to this project from the Ministry of Health Kenya, National Nurses Association of Kenya, the Kenya Paediatric Association and the Nursing Council of Kenya.

Health Services that Deliver for Nursing advisory Group: Mary Nandili (Ministry of Health), Edna Tallan (Nursing Council of Kenya), Alfred Obengo (National Nurses Association of Kenya), Mary Kamau (Coptic hospital), Mary Katunge (Kenya Medical Training College, Nairobi), Grace Gachuiri (Kenyatta University), Grace Onchwari (Ministry of Health), Prof Rachael Musoke (University of Nairobi), Nyakina Orina (Nairobi County), Josephine Aritho (Nairobi County), Odesa Omayo (Kenyatta National Hospital) and Joan Basweti (Nairobi County)

Abbreviations

- HIC

High-income country

- IPSG

International Patient Safety Goals

- IQR

Inter-quartile range

- JCI

Joint Commission International

- LMIC

Low- and middle-income country

- NSIs

Nurse-sensitive indicators

- NQF

National Quality Forum

- UNICEF

United Nations Children’s Fund

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

DG, ME and GAVM designed the study with contributions from DJ and SB. DG, MZ and GS were responsible for the literature review and coordination of the stakeholder meetings. DG, MZ and ME wrote the initial draft of the manuscript with substantial and critical input from all co-authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Systems Research Initiative joint grant provided by the Department for International Development (DFID), United Kingdom; Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC); Medical Research Council (MRC); and Wellcome Trust, grant number MR/M018510/1. ME is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship (#207522). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Scientific and ethical approval for this study was granted by the Kenya Medical Research Institute Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (SERU 3736).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Heal [Internet]. 2018 Nov 1 [cited 2018 Dec 1];6(11):e1196–252. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30196093.

- 2.Griffiths P, Jones S, Maben J, Murrells T. State of the art metrics for nursing : a rapid appraisal. 2008;(October 2015):1–38.

- 3.Redfern SJ, Norman IJ. Measuring the quality of nursing care: a consideration of different approaches. J Adv Nurs. 1990/11/01. 1990;15(11):1260–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mueller C, Karon SL. ANA nurse sensitive quality indicators for long-term care facilities. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004/01/14. 2004;19(1):39–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Chen L, Huang LH, Xing MY, Feng ZX, Shao LW, Zhang MY, et al. Using the Delphi method to develop nursing-sensitive quality indicators for the NICU. J Clin Nurs. 2016/07/13. 2017;26(3–4):502–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Burston S, Chaboyer W, Gillespie B. Nurse-sensitive indicators suitable to reflect nursing care quality: a review and discussion of issues. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(13–14):1785–1795. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Quality Forum. National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Nursing-Sensitive Care: an initial performance measure set. 2004.

- 8.Mccance T, Telford L, Wilson J, Macleod O, Dowd A. Identifying key performance indicators for nursing and midwifery care using a consensus approach. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(7–8):1145–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol [Internet]. 2014;67(12):1291–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25034198. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2018 Oct 2 [cited 2019 Jul 3];169(7):467. Available from: http://annals.org/article.aspx?doi = 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.National Quality Forum. Measure evaluation criteria [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 16]. Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/Measuring_Performance/Submitting_Standards/Measure_Evaluation_Criteria.aspx.

- 13.National Quality Forum. NQF: What we do [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 3]. Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/what_we_do.aspx.

- 14.Murphy GA V, Omondi GB, Gathara D, Abuya N, Mwachiro J, Kuria R, et al. Expectations for nursing care in newborn units in Kenya: moving from implicit to explicit standards. BMJ Glob Heal [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Aug 28];3(2):e000645. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29616146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Keene CM, Aluvaala J, Murphy GAV, Abuya N, Gathara D, English M. Developing recommendations for neonatal inpatient care service categories: Reflections from the research, policy and practice interface in Kenya. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Joint Commission International. International Patient Safety Goals | Joint Commission International [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/improve/international-patient-safety-goals/.

- 17.Joint Commission International. Who is JCI - who we are | Joint Commission International [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/about-jci/who-is-jci/.

- 18.Mark Foulkes. Nursing metrics: measuring quality in patient care. Nurs Stand . 2011;25(42):40–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Maben J, Morrow E, Ball J, Robert G, Griffiths P. High quality care metrics for nursing. Natl Nurs Res Unit, King’s Coll London [Internet]. 2012;(August):1–53. Available from: http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/346019/1/High-Quality-Care-Metrics-for-Nursing%2D%2D%2D%2DNov-2012.pdf.

- 20.Koy V, Yunibhand J, Angsuroch Y. The quantitative measurement of nursing care quality: a systematic review of available instruments. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63(3):490–498. doi: 10.1111/inr.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q [Internet]. 1966;44(No. 3, Pt. 2):166–203. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2690293&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype = abstract. [PubMed]

- 22.Kunaviktikul, Anders, Chontawan, Nuntasupawat, Srisuphan, Pumarporn, et al. Development of indicators to assess the quality of nursing care in Thailand. Nurs Heal Sci. 2005/11/08. 2005;7(4):273–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Zhang Y, Liu L, Hu J, Zhang Y, Lu G, Li G, et al. Assessing nursing quality in paediatric intensive care units: a cross-sectional study in China. Nurs Crit Care. 2016:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Langemo DK, Anderson J, Volden CM. Nursing quality outcome indicators. JONA J Nurs Adm. 2003;32(2):98–105. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MA C, PA H. The Nightingale metrics: nurses at one institution improved outcomes by putting patients “in the best condition for nature to act.”. Am J Nurs [Internet] 2006;106(10):66–70. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=106202997&site=ehost-live.

- 26.Lacey SR, Klaus SF, Smith JB, Cox KS, Dunton NE. Developing measures of pediatric nursing quality. J Nurs Care Qual. 2006/07/04. 2006;21(3):210–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Stratton KM. Pediatric nurse staffing and quality of care in the hospital setting. J Nurs Care Qual [Internet] 2008;23(2):105–114. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00001786-200804000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Pazargadi M, Tafreshi MZ, Abedsaeedi Z, Majd HA, Lankshear AJ. Proposing indicators for the development of nursing care quality in Iran. Int Nurs Rev [Internet]. 2008 Dec [cited 2016 Nov 21];55(4):399–406. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Riehle AI, Hanold LS, Sprenger SL, Loeb JM. Specifying and standardizing performance measures for use at a national level: implications for nursing-sensitive care performance measures. Med Care Res Rev [Internet] 2007;64(2 suppl):64S-81S. Available from: http://mcr.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/1077558707299263. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 5]. Available from: http://www.jointlearningnetwork.org/.

- 31.Safe Care: Basic healthcare standards [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 5]. Available from: https://www.safe-care.org/.

- 32.The Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa (COHSASA) [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 5]. Available from: http://cohsasa.co.za/.

- 33.Hospitals - Achieve Accreditation | Joint Commission International [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/achieve-hospitals/.

- 34.Montalvo I. The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI). Online J Issues Nurs [Internet]. 2007;12(3):http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANA. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=2009867881&site=ehost-live.

- 35.Ranegger R, Hackl WO, Ammenwerth E. Development of the Austrian Nursing Minimum Data Set (NMDS-AT): the third Delphi round, a quantitative online survey. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;212(March 2016):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.All-Party Parliamentary Group on Global Health. Triple impact: how developing nursing will improve health, promote gender equality and support economic growth. 2016.

- 37.Gathara D, Nyamai R, Were F, Mogoa W, Karumbi J, Kihuba E, et al. Moving towards routine evaluation of quality of inpatient pediatric care in Kenya. PLoS One. 2015;10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Reyburn H, Mwakasungula E, Chonya S, Mtei F, Bygbjerg I, Poulsen A, et al. Clinical assessment and treatment in paediatric wards in the north-east of the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Heal Organ. 2008/02/26. 2008;86(2):132–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Hardey M, Payne S, Coleman P. “Scraps”: hidden nursing information and its influence on the delivery of care. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(1):208–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kebede M, Endris Y, Zegeye DT. Nursing care documentation practice: the unfinished task of nursing care in the University of Gondar Hospital. Informatics Heal Soc Care [Internet]. 2017;42(3):290–302. Available from: 10.1080/17538157.2016.1252766. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Asamani JA, Amenorpe FD, Babanawo F, Ofei AMA. Nursing documentation of inpatient care in eastern Ghana. Br J Nurs [Internet] 2014;23(1):48–54. Available from: http://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/10.12968/bjon.2014.23.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Wang N, Hailey D, Yu P. Quality of nursing documentation and approaches to its evaluation: a mixed-method systematic review. J Adv Nurs [Internet]. 2011 1 [cited 2018 Mar 26];67(9):1858–75. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05634.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Chatterjee MT, Moon JC, Murphy R, McCrea D. The “OBS” chart: an evidence based approach to re-design of the patient observation chart in a district general hospital setting. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(960):663–666. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.031872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okaisu EM, Kalikwani F, Wanyana G, Coetzee M. Improving the quality of nursing documentation: an action research project. Curationis [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2020 Feb 13];37(2):E1-11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26864179. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Magnet Model [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.nursingworld.org/organizational-programs/magnet/magnet-model/.

- 46.Tuti T, Bitok M, Malla L, Paton C, Muinga N, Gathara D, et al. Improving documentation of clinical care within a clinical information network: an essential initial step in efforts to understand and improve care in Kenyan hospitals. BMJ Glob Heal [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Jul 16];1(1):e000028. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27398232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.