Abstract

Background

The prevalence of HIV/HCV/HBV/ Treponema pallidum is an essential health issue in China. However, there are few studies focused on foreigners living in China. This study aimed to assess the prevalence and socio-demographic distribution of HIV, HBV, HCV, and T. pallidum among foreigners in Guangzhou in the period of 2010–2017.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted to screen serological samples of 40,935 foreigners from 2010 to 2017 at the Guangdong International Travel Health Care Center in Guangzhou. Samples were tested for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-HCV, syphilis antibody (anti-TPPA) and anti-HIV 1 and 2. We collected secondary data from laboratory records and used multiple logistic regression analyses to verify the association between different factors and the seroprevalence of HIV/HBV/HCV/ T. pallidum.

Results

The prevalence of HBV/HCV/HIV/ T. pallidum was 2.30, 0.42, 0.02, and 0.60%, respectively, and fluctuated slightly for 7 years. The results of multiple logistic regression showed that males were less susceptible to HBV than females (odds ratio [OR] = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.67–0.89). Participants under the age of 20 had a lower risk of HBV (OR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.18–0.35), HCV (OR = 0.06, 95% CI: 0.02–0.18), and T. pallidum (OR = 0. 10, 95% CI: 0.05–0.20) than participants over the age of 50. Participants with an education level below high school were more likely to have HBV (OR = 2.98, 95% CI: 1.89–4.70) than others, and businessmen (OR = 3.02, 95% CI: 2.03–4.49), and designers (OR = 3.83, 95% CI: 2.49–5.90) had a higher risk of T. pallidum than others. Co-infection involved 58 (4.20%) total cases, and the highest co-infection rate was observed for HBV and T. pallidum (2.60%).

Conclusion

The prevalence of HBV/HCV/HIV/ T. pallidum was low among foreigners in Guangzhou. Region, gender, age, educational level, and occupation were risk factors for positive infection.

Keywords: HBV, HCV, HIV, Treponema pallidum, Prevalence, China

Background

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have been recognized as major public health problems in many countries, especially in developing countries [1]. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is considered to be a serious public health problem worldwide, especially in less developed countries. It is estimated that 70% of new chronic HBV infections occur in low-income countries [2]. More so, The Polaris Observatory’s collaborators reported in a survey of 128 countries that the global average HBV prevalence rate was 4.9%, with China, India, Nigeria, Indonesia, and the Philippines accounting for more than 57% of all HBsAg-positive cases [3]. The major burden from HCV infection comes from chronic infection [4], as 184 million individuals worldwide are chronic carriers of HCV [5, 6]. HIV has been spreading from high-risk populations to the general population [7], and 37 million individuals are living with HIV globally. In addition, around six million individuals are infected with T. pallidum [8]. Although T. pallidum had been eliminated from China in the 1960s by providing free screening and treatment, the first resurgent cases were recognized in China in 1979, and China’s national surveillance data show a disturbing steady spread of the disease across the country [9]. T. pallidum has been found to increase HIV infection by two to five times. HIV infection may also increase the spreading of other sexually transmitted diseases, leading to epidemiological synergies between HIV and other STIs [10]. Thus, awareness of co-infection is important because shared transmission pathways and mechanisms may suggest common preventive interventions. In addition, HBV, HCV, HIV, and syphilis can also be transmitted by mother-to-child or iatrogenic transmission, such as contaminated blood or unsterilized dental needles and syringes.

Guangdong is a province in the south of China with an estimated population of 300,000 foreigners. Guangzhou is the capital city of Guangdong. A population of foreigners lives in Guangzhou mostly for economic reasons. Currently, the prevalence of STIs among this population has not been adequately confirmed. To assess the prevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV, and T. pallidum among foreigners living in Guangzhou, we designed a cross-sectional study from 2010 to 2017.

Methods

Study design, setting, and subjects

A cross-sectional study was approved by the “Guangdong International Travel Healthcare Center Institutional Review Board Committee.” All foreigners arriving in Guangzhou should attend Guangdong International Travel Health Care for physical examination within 6 months. Except for people with incomplete data (The data is not shown in the text), all the other foreigners were included in our study. This study was conducted anonymously. Within the study period, a total of 40, 935 people participated serological tests, including Antibody test for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), Antibody test for Hepatitis C Virus (anti HCV), Antibody test for HIV 1 and 2 (anti HIV), and T. pallidum gelatin agglutination test (anti T. pallidum/TPPA). We collected secondary data for analysis.

Statistical analysis

The difference in the prevalence of STIs between groups was compared using the χ2 tests. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to explore the factors associated with seropositivity. The statistically significant variables, according to the χ2 tests, were included in the multiple logistic regression models to compute the adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The significance level was set at P < 0.05. All of the analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Of the 40, 935 participants, 23,309 (56.94%) were male and 17,626 (43.06%) were female. The average ages of the participates were 32.59 ± 11.86 years, with a range of 0–97 years (supplementary Table 1). As shown in Table 1, 45.90% of the participants were undergraduate students (N = 18,791), while 72.75% had a college education level or less. The majority of participants were from Europe (31.93%) and North America (22.21%). About 29.56% were students, followed by businessmen (24.08%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants, Guangzhou, 2010–2017

| Characteristic | Number % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 40,935 | 100.00 |

| Exam year | ||

| 2010 | 4089 | 9.99 |

| 2011 | 4665 | 11.40 |

| 2012 | 4464 | 10.91 |

| 2013 | 5287 | 12.92 |

| 2014 | 5907 | 14.43 |

| 2015 | 5461 | 13.34 |

| 2016 | 5605 | 13.69 |

| 2017 | 5457 | 13.33 |

| Region | ||

| Africa | 5927 | 14.48 |

| Europe | 13,071 | 31.93 |

| North America | 9091 | 22.21 |

| South America | 2269 | 5.54 |

| Oceania | 693 | 1.69 |

| Asia | 9884 | 24.15 |

| Gender | ||

| male | 23,309 | 56.94 |

| female | 17,626 | 43.06 |

| Age group | ||

| < 20 | 6492 | 15.86 |

| 20–29 | 14,236 | 34.78 |

| 30–39 | 9804 | 23.95 |

| 40–49 | 5557 | 13.58 |

| ≥ 50 | 4846 | 11.84 |

| Education level | ||

| Less than high school | 371 | 0.91 |

| High school | 10,620 | 25.94 |

| Undergraduate | 18,791 | 45.90 |

| Bachelor degree or above | 7582 | 18.52 |

| Unknown | 3571 | 8.72 |

| Occupation | ||

| Business | 9856 | 24.08 |

| Designers/science education | 4818 | 11.77 |

| Students | 12,102 | 29.56 |

| Unemployed | 2537 | 6.20 |

| Others | 11,622 | 28.39 |

| STIs | ||

| HBV | 943 | 2.30 |

| HCV | 173 | 0.42 |

| HIV | 7 | 0.02 |

| TPPA | 246 | 0.60 |

Prevalence of STIs

The prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV, and T. pallidum was 2.30, 0.42, 0.02, and 0.60%, respectively (Table 1), and fluctuated slightly over the 7 years covered by the study (Fig. 1). It was found that 58 (4.2%) cases had multiple infections (Fig. 2), and the highest co-infection rate was observed for HBV and T. pallidum (2.6%) (supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1.

The positive rate of STIs screening during 2010–2017

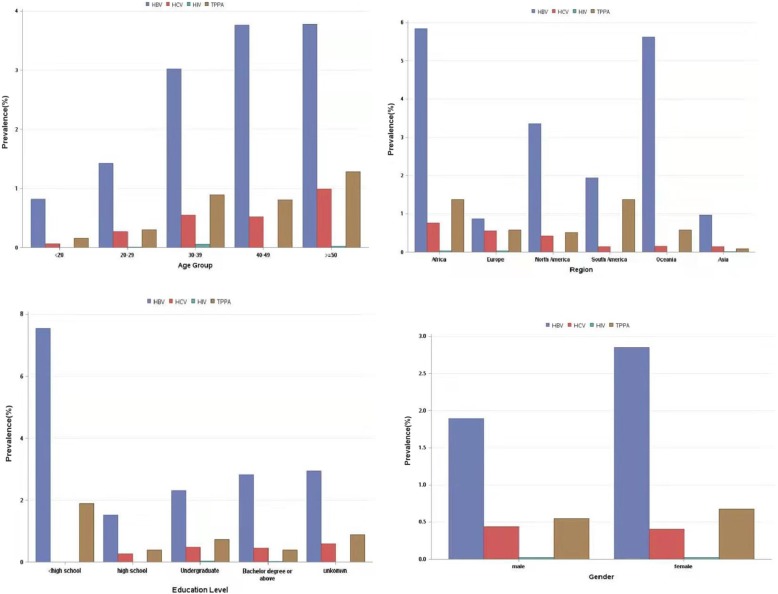

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV and T. pallidum by age, region, education level, and gender groups

As shown in Table 2, females had a higher prevalence of HBV (χ2 = 7.58, P = 0.01) than males (see Table 2, Fig. 3). There were no differences over the exam year among the STIs. The seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV, and T. pallidum presented was different by geographical regions (see Table 2, Fig. 3). There was a significant difference in the seropositivity of HBV between the different age groups (χ2 = 14.15, P = 0.01). Educational level differences were also observed in the seroprevalence of HBV (χ2 = 14.94, P = 0.01) and T. pallidum (χ2 = 14.09, P = 0.01). Considering the occupation, there were significant differences for HBV (χ2 = 64.21, P < 0.001), HCV(χ2 = 26.19, P < 0.001) and T. pallidum (χ2 = 155.94, P < 0.001). However, perhaps as a consequence of the low number of HIV positive cases, the seropositivity of HIV was not different among the different social demographic characteristics.

Table 2.

Prevalence of HBV/HCV/HIV/TPPA among individuals with different social demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Total | No. Positive, (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | χ2 | P | HCV | χ2 | P | HIV | χ2 | P | TPPA | χ2 | P | ||

| Exam year | |||||||||||||

| 2010 | 155 | 99 (2.42) | 13.61 | 0.06 | 16 (0.39) | 8.72 | 0.27 | 0 (0) | 18.85a | 0.001a | 40 (0.98) | 11.70 | 0.11 |

| 2011 | 169 | 127 (2.72) | 17 (0.36) | 0 (0) | 25 (0.54) | ||||||||

| 2012 | 131 | 98 (2.20) | 16 (0.36) | 0 (0) | 17 (0.38) | ||||||||

| 2013 | 166 | 117 (2.21) | 21 (0.40) | 0 (0) | 28 (0.53) | ||||||||

| 2014 | 210 | 133 (2.25) | 31 (0.52) | 5 (0.08) | 41 (0.69) | ||||||||

| 2015 | 169 | 109 (2.00) | 31 (0.57) | 2 (0.04) | 27 (0.49) | ||||||||

| 2016 | 187 | 137 (2.44) | 19 (0.34) | 0 (0) | 31 (0.55) | ||||||||

| 2017 | 182 | 123 (2.25) | 22 (0.40) | 0 (0) | 37 (0.68) | ||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| Male | 673 | 440 (1.89) | 7.58 | 0.01 | 102 (0.44) | 7.61 | 0.01 | 4 (0.02) | 0.18a | 0.67a | 127 (0.54) | 0.73 | 0.39 |

| Female | 696 | 503 (2.85) | 71 (0.40) | 3 (0.02) | 119 (0.68) | ||||||||

| Region | |||||||||||||

| Africa | 474 | 346 (5.84) | 125.37 | < 0.001 | 45 (0.76) | 67.12 | < 0.001 | 2 (0.03) | 8.91a | 0.11a | 81 (1.37) | 67.96 | < 0.001 |

| Europe | 266 | 114 (0.87) | 72 (0.55) | 4 (0.03) | 76 (0.58) | ||||||||

| North America | 389 | 305 (3.35) | 38 (0.42) | 0 (0) | 46 (0.51) | ||||||||

| South America | 78 | 44 (1.94) | 3 (0.13) | 0 (0) | 31 (1.37) | ||||||||

| Oceania | 44 | 39 (5.63) | 1 (0.14) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.58) | ||||||||

| Asia | 118 | 95 (0.96) | 14 (0.14) | 1 (0.01) | 8 (0.08) | ||||||||

| Age group | |||||||||||||

| < 20 | 67 | 53 (0.82) | 14.15 | 0.01 | 4 (0.06) | 8.02 | 0.09 | 0 (0) | 6.41a | 0.17a | 10 (0.15) | 5.94 | 0.20 |

| 20–29 | 283 | 202 (1.42) | 38 (0.27) | 1 (0.01) | 42 (0.30) | ||||||||

| 30–39 | 442 | 296 (3.02) | 54 (0.55) | 5 (0.05) | 87 (0.89) | ||||||||

| 40–49 | 283 | 209 (3.76) | 29 (0.52) | 0 (0) | 45 (0.81) | ||||||||

| ≥ 50 | 294 | 183 (3.78) | 48 (0.99) | 1 (0.02) | 62 (1.28) | ||||||||

| Education level | |||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 35 | 28 (7.55) | 14.94 | 0.01 | 0 (0) | 5.70 | 0.22 | 0 (0) | 2.81a | 0.59a | 7 (1.89) | 14.09 | 0.01 |

| High school | 232 | 161 (1.52) | 28 (0.26) | 1 (0.01) | 42 (0.40) | ||||||||

| Undergraduate | 666 | 435 (2.31) | 90 (0.48) | 5 (0.03) | 136 (0.82) | ||||||||

| Bachelor degree or above | 278 | 214 (2.82) | 34 (0.45) | 1 (0.01) | 29 (0.38) | ||||||||

| Others | 158 | 105 (2.94) | 21 (0.59) | 0 (0) | 32 (0.9) | ||||||||

| Occupation | |||||||||||||

| Businessmen | 227 | 127 (1.29) | 64.21 | < 0.001 | 14 (0.14) | 26.19 | < 0.001 | 1 (0.01) | 3.51a | 0.48a | 85 (0.86) | 155.94 | < 0.001 |

| Designers | 200 | 105 (2.18) | 23 (0.48) | 2 (0.04) | 70 (1.45) | ||||||||

| Students | 340 | 250 (2.07) | 33 (0.27) | 3 (0.02) | 54 (0.45) | ||||||||

| Unemployed | 24 | 21 (0.83) | 1 (0.04) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.08) | ||||||||

| Others | 578 | 440 (3.79) | 102 (0.88) | 1 (0.01) | 35 (0.3) | ||||||||

a for likelihood ratio chi-square; No., OR, N/A, and 95% CI represent Number, Odd Rate, No data, and 95% confidence interval, respectively

Fig. 3.

Diagram showing overlap of HBV, HCV, TPPA, and HIV

Related factors of STIs

The results of multiple logistic regression showed that the seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV, and T. pallidum varies according to the geographical region of origin. Infection with HBV, HCV, and T. pallidum was the most prevalent in foreigners from Africa. Participants from Africa (OR = 9.13, 95% CI: 6.84–12.19), North America (OR = 2.74, 95% CI: 2.08–3.60), South America (OR = 2.22, 95% CI:1.49–3.30), and Oceania (OR = 6.05, 95% CI: 4.02–9.10) had a higher seroprevalence of HBV than those from Asia. The seroprevalence of HCV in foreigners from Africa (OR = 5.33, 95% CI: 2.88–9.87) and Europe (OR = 3.06, 95% CI: 1.72–5.46) was higher than in those from Asia, and the seroprevalence of T. pallidum in Asiatic foreigners was lower than in those from Africa (OR = 17.18, 95% CI: 8.17–36.11) and South America (OR = 19.30, 95% CI: 8.81–42.29).

Among age groups, a significant increase in the positive rate of HBV was observed in the 40–49-year-old participants (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.85–1.30) (see Table 3), and people under 50 had a lower seroprevalence of HCV than people over 50, especially those below 20 (OR = 0.06, 95% CI: 0.02–0.18). The same is true for T. pallidum (P < 0.001). Educational level differences in seroprevalences were also observed, as people with below high school diplomas had a higher seroprevalence of HBV than other groups (OR = 2.98, 95% CI: 1.89–4.69), and people with bachelor degree had a higher seroprevalence of HBV than other groups (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.07–1.78).

Table 3.

Association of HBV/HCV with different social demographic characteristics

| HBV | HCV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No. (%) | OR (95%CI) | P-Values | No. (%) | OR (95%CI) | P-Values |

| Exam date | 0.34 | 0.50 | ||||

| 2010–2012 | 324(2.45) | 1.07 (0.86,1.33) | 0.20 | 49(0.37) | 0.98 (0.58,1.64) | 0.68 |

| 2014–2017 | 502(2.23) | 0.93 (0.75,1.15) | 0.15 | 103(0.46) | 1.12 (0.69,1.82) | 0.48 |

| 2013 | 117(2.21) | 1.00 | N/A | 21(0.40) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Region | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Africa | 346 (5.84) | 9.13 (6.84,12.19) | < 0.001 | 45(0.76) | 5.33(2.88,9.87) | < 0.001 |

| Europe | 114 (0.87) | 1.04 (0.77,1.40) | 0.79 | 72(0.55) | 3.06 (1.72,5.46) | < 0.001 |

| North America | 305 (3.35) | 2.74 (2.08,3.60) | < 0.001 | 38(0.42) | 1.53 (0.82,2.86) | 0.18 |

| South America | 44 (1.94) | 2.22 (1.49,3.30) | < 0.001 | 3(0.13) | 0.72 (0.21,2.51) | 0.60 |

| Oceania | 39 (5.63) | 6.05 (4.02,9.10) | < 0.001 | 1(0.14) | 0.56 (0.07,4.27) | 0.57 |

| Asia | 95 (0.96) | 1.00 | N/A | 14(0.14) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Gender | < 0.001 | 0.18 | ||||

| Male | 440(1.89) | 0.77 (0.67,0.89) | 102(0.44) | 1.25 (0.89,1.74) | ||

| Female | 503(2.85) | 1.00 | N/A | 71(0.40) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Age | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 20 | 53(0.82) | 0.25 (0.18,0.35) | < 0.001 | 4(0.06) | 0.06 (0.02,0.18) | < 0.001 |

| 20–29 | 202(1.42) | 0.38 (0.31,0.48) | < 0.001 | 38(0.27) | 0.19 (0.13,0.30) | < 0.001 |

| 30–39 | 296(3.02) | 0.76 (0.62,0.94) | 0.01 | 54(0.55) | 0.43 (0.29,0.65) | < 0.001 |

| 40–49 | 209(3.76) | 1.05 (0.85,1.30) | 0.64 | 29(0.52) | 0.48 (0.30,0.76) | 0.002 |

| ≥ 50 | 183(3.78) | 1.00 | N/A | 48(0.99) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Educational level | < 0.001 | 0.23 | ||||

| Less than high school | 28(7.55) | 2.98 (1.89,4.69) | < 0.001 | 0(0.00) | < 0.00(< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.12 |

| High school | 161(1.52) | 1.39 (1.05,1.84) | 0.02 | 28(0.26) | 1.10 (0.58,2.08) | 0.18 |

| Undergraduate | 435(2.31) | 0.83 (0.67,1.04) | 0.11 | 90(0.48) | 0.74 (0.45,1.24) | 0.17 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 214(2.82) | 1.38 (1.07,1.78) | 0.01 | 34(0.45) | 0.95 (0.52,1.73) | 0.54 |

| Others | 105(2.94) | 1.00 | N/A | 21(0.59) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Occupation | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Businessmen | 127(1.29) | 0.31 (0.25,0.38) | < 0.001 | 14(0.14) | 0.16 (0.09,0.28) | < 0.001 |

| Designers | 105(2.18) | 0.30 (0.24,0.38) | < 0.001 | 23(0.48) | 0.40 (0.25,0.65) | < 0.001 |

| Students | 250(2.07) | 0.57 (0.48,0.68) | < 0.001 | 33(0.27) | 0.36 (0.24,0.54) | < 0.001 |

| Unemployed | 21(0.83) | 0.16 (0.10,0.25) | < 0.001 | 1(0.04) | 0.04 (0.01,0.31) | 0.002 |

| Others | 440(3.79) | 1.00 | N/A | 102(0.88) | 1.00 | N/A |

No., OR, N/A and 95% CI represent Number, Odd Rate, No data and 95% confidence interval, respectively

For occupation, there were significant differences in HBV for businessmen (OR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.25–0.38), designers (OR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.24–0.38), students (OR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.48–0.68), and unemployed (OR = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.10–0.25) compared to others (Table 3). Notably, T. pallidum had a higher prevalence among businessmen (OR = 3.02, 95% CI: 2.03–4.49) and designers (OR = 3.83, 95% CI: 2.49–5.90) than in the other groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations of HIV/TPPA with different social demographic characteristics

| HIV | TPPA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No.(%) | OR(95%CI) | P-Values | No. (%) | OR(95%CI) | P-Values |

| Exam date | 0.99 | 0.33 | ||||

| 2010–2012 | 0(0.00) | 0.96 (< 0.00, > 999.) | 0.92 | 49(0.37) | 1.27 (0.82,1.96) | 0.24 |

| 2014–2017 | 7(0.03) | > 999. (< 0.00, > 999.) | 0.78 | 103(0.46) | 1.12 (0.73,1.71) | 0.96 |

| 2013 | 0(0.00) | 1.00 | N/A | 21(0.40) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Region | 0.50 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Africa | 2 (0.03) | 1.27 (0.05,32.17) | 0.34 | 81(1.37) | 17.18(8.17,36.11) | < 0.001 |

| Europe | 4 (0.03) | 1.03 (0.06,18.35) | 0.18 | 76(0.58) | 7.34 (3.53,15.27) | < 0.001 |

| North America | 0 (0.00) | < 0.00 (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.14 | 46(0.51) | 5.00 (2.34,10.68) | < 0.001 |

| South America | 0 (0.00) | < 0.00 (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.54 | 31(1.37) | 19.30 (8.81,42.29) | < 0.001 |

| Oceania | 0 (0.00) | 0.00 (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.71 | 4(0.58) | 4.58 (1.36,15.42) | 0.01 |

| Asia | 1 (0.01) | 1.00 | N/A | 8(0.08) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Gender | 0.95 | 0.65 | ||||

| male | 4 (0.02) | 1.14 (0.21,6.33) | 127(0.54) | 0.97 (0.73,1.28) | ||

| female | 3 (0.02) | 1.00 | N/A | 119(0.68) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Age | 0.46 | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 20 | 0 (0) | < 0.00 (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.98 | 10(0.15) | 0.10 (0.05,0.20) | < 0.001 |

| 20–29 | 1 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.01,3.13) | 0.46 | 42(0.30) | 0.16(0.10,0.24) | < 0.001 |

| 30–39 | 5 (0.05) | 1.42 (0.16,12.90) | 0.39 | 87(0.89) | 0.51 (0.36,0.72) | < 0.001 |

| 40–49 | 0 (0) | < 0.00 (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.98 | 45(0.81) | 0.54 (0.37,0.81) | 0.003 |

| ≥ 50 | 1 (0.02) | 1.00 | N/A | 62(1.28) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Educational level | 0.87 | 0.12 | ||||

| Less than high school | 0 (0.00) | 1.41 (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.81 | 7(1.89) | 0.92 (0.38,2.20) | 0.30 |

| High school | 1 (0.01) | 626.90 (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.69 | 42(0.40) | 0.68 (0.41,1.11) | 0.78 |

| Undergraduate | 5 (0.03) | > 999. (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.29 | 136(0.82) | 0.67 (0.44,1.02) | 0.84 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1 (0.01) | 409.00 (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.58 | 29(0.38) | 0.48 (0.28,0.83) | 0.06 |

| Others | 0 (0.00) | 1.00 | N/A | 32(0.90) | 1.00 | N/A |

| Occupation | 0.39 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Businessmen | 1 (0.01) | 0.98 (0.06,15.98) | 0.46 | 85(0.86) | 3.02 (2.03,4.49) | < 0.001 |

| Designers | 2 (0.04) | 3.05 (0.26,35.20) | 0.19 | 70(1.45) | 3.83 (2.49,5.90) | < 0.001 |

| Students | 3 (0.02) | 3.55 (0.36,35.37) | 0.23 | 54(0.45) | 1.98 (1.29,3.06) | 0.002 |

| Unemployed | 0 (0.00) | 0.00 (< 0.00,> 999.) | 0.47 | 2(0.08) | 0.32 (0.08,1.34) | 0.12 |

| Others | 1 (0.01) | 1.00 | N/A | 35(0.30) | 1.00 | N/A |

No., OR, N/A, and 95% CI represent Number, Odd Rate, No data, and 95% confidence interval, respectively

Discussion

There is an epidemic in China of sexually transmitted diseases and the potential for its continued growth in the future. In addition to sexual transmission, these diseases can also be transmitted through mother-to-child transmission, hospital transmission and so on, so controlling and preventing the spread of STIs are now on the agenda [11, 12]. China set out to expand the comprehensive control program consisting of primary and secondary prevention strategies to ensure that STIs can be prevented and infected individuals can be diagnosed and treated in a timely fashion, especially high-risk individuals [13]. However, available data about the prevalence of STIs in foreigners are limited. This is the first large-scale study that detected the seroprevalences of HBV, HCV, HIV, and T. pallidum among foreigners in China.

Of the 40, 935 participants involved, 3.20% (N = 1311) had a single infection, and 0.14% (N = 58) had multiple infections. A recent study in China showed that the prevalence of HBV in people aged 1–4 years, 5–14 years, and 15–29 years was 0.32, 0.94, and 4.38%, respectively [14], in this research, the seropositivity of HBV was 2.30% (N = 943), with the increase of age, the HBV infection rate gradually increased and peaked in the group aged over 50 years, which was in accordance with data for the general population. Foreigners from Africa had the highest proportion of positive HBV rate (5.84%), which is higher than the 4.7% reported in Ethiopia, and lower than the 7.51, 11.2, and 14.96% reported in Benin [15], Cameroon [16], and Burkina Faso [17], respectively.

HCV seroprevalence among foreigners was 0.42%, which is similar to the 0.43% reported in the general population in 2006 in China [18], and it is significantly lower than 2.8%, the average level in the world [19]. Similarly, Africa had the highest rate of HCV infection (0.76%), a value that is higher than the 0.5% reported in Portharcourt [20] and the 0.4% in Ethiopia [21].

Recently, it has been reported that the seroprevalence of T. pallidum ranged from 0.31 to 0.70% among blood donors in different areas of China [22–24]. In our study, the seroprevalence of T.pallidum (0.60%) was similar in Guangzhou (0.66%) in 2010 [22], and higher than in Nanjing(0.36%) and Xi’an [23]. Africa and South America had the highest rate of T.pallidum infection. In sub-Saharan Africa, T. pallidum still remains a severe public health problem [25]. When compared with African countries, the seroprevalence of T. pallidum infection in our study was significantly lower.

The seroprevalence of HIV in this study was 0.02%. The prevalence rate of HIV infection reported in Guangzhou and Nanjing is 0.02 and 0.08%, respectively [26], whereas in Western China the prevalence of HIV in donors was 0.31% [27, 28]. It is worth noting that there were seven HIV infection cases in total, and five cases were undergraduates, suggesting that college students are still the main group of HIV infection. The prevalence of STIs co-infection was 4.20% in foreigners, and the HBV/ T. pallidum co-infection had the maximum proportion. There were no cases involving HIV with any other pathogens. It is possible that the policy related to HIV infection in the country of origin may explain the low prevalence observed in this research. For instance, some travellers may not be allowed to go abroad due to a HIV positive test in their country.

There are several limitations to this study that should be mentioned. First, this article used the secondary data, so the genotypes of various sexually transmitted diseases pathogens were not clear. Second, HIV cases were too small to perform a multiple linear regression, decision trees, or other statistical methods used for analysis [29]. Third, all foreigners who arrive in Guangzhou will accept a physical examination, but some data are incomplete and we removed these data from our study, which may bias the results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the epidemiologic data presented in this paper showed the presence of STIs prevalence in foreigners living in Guangzhou. This study showed a low prevalence of STIs among foreigners. Some prevalence were consistent with the local trends. During the survey period, there was no significant decline trend in the prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV, and T. pallidum, so we highlight the need to strengthen the current surveillance program. More observation studies on STIs burden, risk factors, and interventions are needed to provide a solid base for planning and policy change [30, 31]. Furthermore, it is essential to take comprehensive measures including this particular group to control and prevent sexually transmitted infections.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table 1. The prevalence of HBV/HCV/HIV/TPPA detected in samples of 40,935 participants. (XLS 6437 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- T. pallidum

Treponema pallidum

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B viral surface antigen

- Anti-TPPA

Treponemal Pallidum Particle Agglutination

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- STIs

Sexually transmitted infections

Authors’ contributions

BC designed the study and wrote the draft of the manuscript. JMZ and JW provided the raw data. LPH, MQF, JLW and YCD analyzed the data. MQF, SXT, JLW and CSW critically revised the article for the important intellectual content. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by funding from the Guangzhou Health Care Collaborative Innovation Major Project (No.201704020219) and co-funded by the Project of the Guangdong Key Laboratory of Tropical Diseases (RDBYJ2018001), administered by Southern Medical University. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper.

Availability of data and materials

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Guangdong International Travel Healthcare Center Institutional Review Board Committee. As only secondary data was used in this study, consent to participate was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Benard Chimungu, Muqing Fu and Jian Wu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jianming Zhang, Email: gzwcs@smu.edu.cn.

Chengsong Wan, Email: gzzhangjm@163.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12879-020-04995-8.

References

- 1.Karabaev BB, Beisheeva NJ, Satybaldieva AB, Ismailova AD, Pessler F, Akmatov MK. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus, Treponema pallidum, and co-infections among blood donors in Kyrgyzstan: a retrospective analysis (2013–2015). Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Nayagam S, Thursz M, Sicuri E, Conteh L, Wiktor S, Low-Beer D, Hallett TB. Requirements for global elimination of hepatitis B: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(12):1399–1408. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okoroiwu HU, Okafor IM, Asemota EA, Okpokam DC. Seroprevalence of transfusion-transmissible infections (HBV, HCV, syphilis and HIV) among prospective blood donors in a tertiary health care facility in Calabar, Nigeria; an eleven years evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45(4):529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aparna S, Johannes H, Rafael TM, Gérard K, J Rdis JO. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet (London, England). 2015;386(10003):1515–1517. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Mohd HK, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333–1342. doi: 10.1002/hep.26141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou H, Zhang L, Chow EPF, Tang W, Wang Z. Testing for HIV/STIs in China: challenges, opportunities, and innovations. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1–3. doi: 10.1155/2017/2545840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, Stevens G, Gottlieb S, Kiarie J, Temmerman M. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e143304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruan Y, Luo F, Jia Y, Li X, Li Q, Liang H, Zhang X, Li D, Shi W, Freeman JM, et al. Risk factors for syphilis and prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B and C among men who have sex with men in Beijing, China: implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):663–670. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9503-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss GB, Kreiss JK. The interrelationship between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Med Clin North Am. 1990;74(6):1647–1660. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7125(16)30500-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, Yu Y, Hu Q, Yan H, Wang Z, Lu L, Zhuang M, Chen X, Fu J, Tang W, et al. Treatment-seeking behaviour and barriers to service access for sexually transmitted diseases among men who have sex with men in China: a multicentre cross-sectional survey. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0219-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Chow EPF, Su S, Yiu WL, Zhang X, Iu KI, Tung K, Zhao R, Sun P, Sun X, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence, trends, and geographical distribution of HIV among Chinese female sex workers (2000–2011): implications for preventing sexually transmitted HIV. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;39:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen XS, Peeling RW, Yin YP, Mabey DC. The epidemic of sexually transmitted infections in China: implications for control and future perspectives. BMC Med. 2011;9:111. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui F, Shen L, Li L, Wang H, Wang F, Bi S, Liu J, Zhang G, Wang F, Zheng H, et al. Prevention of chronic hepatitis B after 3 decades of escalating vaccination policy, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(5):765–772. doi: 10.3201/eid2305.161477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loua A, Sonoo J, Musango L, Nikiema JB, Lapnet-Moustapha T. Blood safety status in WHO African region countries: lessons learnt from Mauritius. J Blood Transfus. 2017;2017:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Nwobegahay J, Achiangia Njukeng P, Kengne M, Roger Ayangma C, Mbozo O, Abeng E, Nkeza A, Tamoufe U: Prevalence of Hepatitis B virus infection among blood donors at the Yaounde Military Hospital, Cameroon. Micro Res In. 2016;2(4):6–10.

- 17.Bala J, Kawo AH, Dauda M, Musa Sarki A, Magaji N, Aliyu I, Sani N. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among blood donors in some selected hospitals in Kano, Nigeria: Res J Microbiol. 2012;3(6):217–22.

- 18.Liakina V, Valantinas J. Anti-HCV prevalence in the general population of Lithuania. Med Sci Mo. 2012;18(3):PH28–PH35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Toy M, Onder O, Marschall T, Bozdayi M, Schalm S, Borsboom G, van Rosmalen J, Richardus J, Yurdaydìn C. Age- and region-specific hepatitis B prevalence in Turkey estimated using generalized linear mixed models: A systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Erhabor O, Ejele OA, Nwauche CA. The risk of transfusion-acquired hepatitis-C virus infection among blood donors in Port Harcourt: the question of blood safety in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2006;9(1):18–21. [PubMed]

- 21.Mohammed Y, Bekele A. Seroprevalence of transfusion transmitted infection among blood donors at Jijiga blood bank, Eastern Ethiopia: retrospective 4 years study. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(1):129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Li C, Xiao X, Yin H, He M, Li J, Dai Y, Fu Y, Ge J, Yang Y, Luan Y, et al. Prevalence and prevalence trends of transfusion transmissible infections among blood donors at four Chinese regional blood centers between 2000 and 2010. J Transl Med. 2012;10(1):176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Ji Z, Li C, Lv Y, Cao W, Chen Y, Chen X, Tian M, Li J, An Q, Shao Z: The prevalence and trends of transfusion-transmissible infectious pathogens among first-time, voluntary blood donors in Xi'an, China between 1999 and 2009. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;17(4):e256–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Yan S, Ying B, Max P, Carolina Oi Lam U. Prevalence and trend of major transfusion-transmissible infections among blood donors in Western China, 2005 through 2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Yang S, Jiao D, Liu C, Lv M, Li S, Chen Z, Deng Y, Zhao Y, Li J. Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses, and Treponema pallidum infections among blood donors at Shiyan, Central China. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Rockstroh J, David Hardy W. Current treatment options for hepatitis C patients co-infected with HIV. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10(6):689–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Martin‐Carbonero L, et al. Liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C and persistently normal liver enzymes: influence of HIV infection. J Viral Hepatitis. 2009;16(11):790–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.De Ledinghen V, Barreiro P, Foucher J, Labarga P, Castera L, Vispo ME, Bernard PH, Martin‐Carbonero L, Neau D, García‐Gascó P, et al. Liver fibrosis on account of chronic hepatitis C is more severe in HIV-positive than HIV-negative patients despite antiretroviral therapy. J Viral Hepatitis. 2008;15(6):427–433. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Verhofstede C, Fransen K, Van Den Heuvel A, Van Laethem K, Ruelle J, Vancutsem E, Stoffels K, Van den Wijngaert S, Delforge M, Vaira D, et al. Decision tree for accurate infection timing in individuals newly diagnosed with HIV-1 infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Zhu B, Liu J, Fu Y, Zhang B, Mao Y. Spatio-temporal epidemiology of viral hepatitis in China (2003–2015): implications for prevention and control policies. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2018;15(4):661. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wendland EM, Horvath JDC, Kops NL, Bessel M, Caierão J, Hohenberger GF, Domingues CM, Maranhão AGK, de Souza FMA, Benzaken AS. Sexual behavior across the transition to adulthood and sexually transmitted infections. Medicine. 2018;97(33):e11758. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table 1. The prevalence of HBV/HCV/HIV/TPPA detected in samples of 40,935 participants. (XLS 6437 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.