Abstract

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is common in cardiovascular disease. It is associated with adverse clinical outcomes for patients who had undergone coronary artery bypass and valve operations. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on the midterm outcomes of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy who underwent septal myectomy.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the data of 67 hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who underwent septal myectomy from two medical centers in China from 2011 to 2018. A propensity score–matched cohort of 134 patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus was also analyzed.

Results

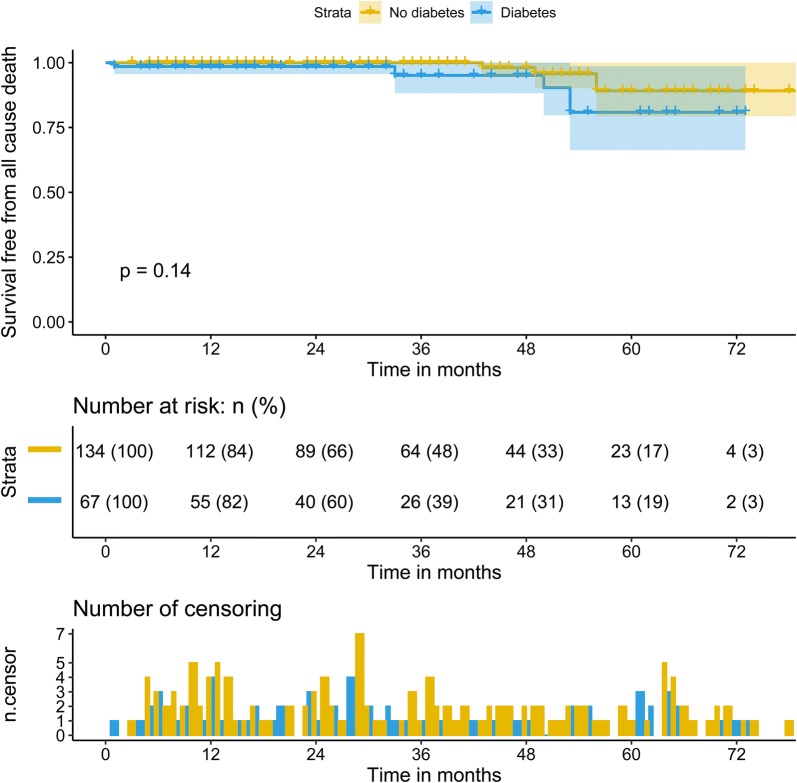

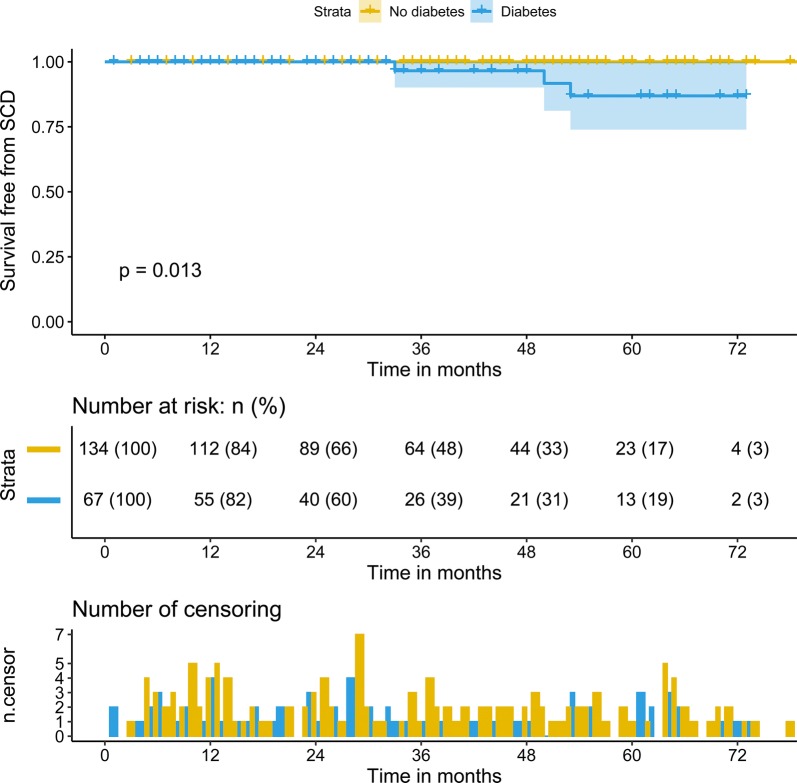

During a median follow-up of 28.0 (interquartile range: 13.0–3.0) months, 9 patients died. The cause of death of all of these patients was cardiovascular, particularly sudden cardiac death in 3 patients. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus had a higher rate of sudden cardiac death (4.5% vs. 0.0%, p = 0.04). The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that the rates of predicted 3-year survival free from cardiovascular death (98.1% vs. 95.1%, p = 0.14) were similar between the two groups. However, the rates of predicted 3-year survival free from sudden cardiac death (100% vs. 96.7%, p = 0.01) were significantly higher in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus than in those with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, after adjustment for age and sex, only N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (hazards ratio: 1.002, 95% confidence interval: 1.000–1.005, p = 0.02) and glomerular filtration rate ≤ 80 ml/min (hazards ratio: 3.23, 95% confidence interval: 1.34–7.24, p = 0.047) were independent risk factors for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Conclusions

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus have similar 3-year cardiovascular mortality after septal myectomy. However, type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with higher sudden cardiac death rate in these patients. In addition, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and glomerular filtration rate ≤ 80 ml/min were independent risk factors among hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Septal myectomy, Sudden cardiac death, Cardiovascular death

Background

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a disease state characterized by unexplained left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy associated with nondilated ventricular chambers in the absence of other cardiac or systemic diseases. It is considered a common inherited heart disease and has a population prevalence of 1 in 500 [1, 2]. Approximately two-thirds of patients have left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction known as hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). If the symptoms of these patients are refractory to optimal medical therapy, surgery is recommended.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is highly common among patients with cardiovascular disease and is associated with increased burden of morbidity and hospitalization [3]. The functional changes occurring in DM can significantly alter the hemodynamic stress on the heart. It is an established risk factor for cardiovascular disease and increases the risk of cardiovascular mortality [4]. In addition, previous studies have reported that type 2 DM (T2DM) is associated with adverse cardiovascular events after coronary artery bypass and valve operations [5–7]. However, the effect of T2DM on clinical outcomes for HCM patients who had undergone septal myectomy is not well studied. We aimed to evaluate the effect of T2DM on the clinical outcomes of patients who underwent septal myectomy.

Methods

Aim, design, and setting

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of T2DM on the clinical outcomes of patients who underwent septal myectomy. This retrospective study was performed using data from two medical centers in Beijing, China.

Study population

We retrospectively studied the data of 67 patients with HOCM and T2DM from Fuwai Hospital (47 patients) and Anzhen Hospital (20 patients) between 2011 and 2018. A control group (patients without DM) was generated from the two centers and the patients were matched in a ratio of 2:1 based on age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and prevalence of hypertension and hyperlipemia. These patients were randomly selected from subjects who underwent septal myectomy during the same period. The diagnostic criteria of HCM mainly included an unexplained septal hypertrophy with a thickness more than 15 mm according to guidelines [1, 2]. The indications for septal myectomy were severe symptoms or syncope or near-syncope despite optimal medical therapy and LVOT gradient > 50 mmHg at rest or with provocation. The diagnosis of DM was obtained from the clinical chart at the time of evaluation. The details of the surgical methods were described in our previous studies [8, 9]. Concomitant procedures were performed according to the results of the preoperative evaluation and intraoperative exploration. History of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT; defined as an episode of consecutive ventricular beats with a rate of at least 100 bpm and a maximum episode length of 30 s) and atrial fibrillation (AF) was recorded, based on history, electrocardiograms, and Holter monitoring in all patients.

Echocardiography and cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging

Echocardiographic examinations were performed on patients using an E9 ultrasound system. The thicknesses of the interventricular septum and ventricular wall were determined during diastole. Aside from the maximum thickness, the representative interventricular septal thickness, which is usually the thickness of the point 25 mm under the right coronary sinus nadir, was also recorded to indicate overall thickness. The LVOT gradient was calculated using the simplified Bernoulli equation. Pulmonary hypertension was defined as a pulmonary artery systolic pressure ≥ 35 mmHg. The measurements of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were determined by following the American Society of Echocardiography recommendations [10].

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) examinations were performed using a 1.5-T MR scanner (Magnetom Avanto; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). Cine scans in cardiac short- and long-axis views were acquired by applying true imaging with steady-stage precession sequence (TrueFISP). Image analysis using a commercial imaging workstation (Siemens Medical Systems). LVEF and indexed LV mass and volume were measured by analyzing the short-axis cine image. The inner and outer myocardial edges were manually delineated. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) was determined semi-automatically as a percentage of the total myocardium and defined as having an intensity > 6 standard deviation above the normal myocardium according to a previous study [11]. Right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) was measured using volumetric measurements on CMR [12].

Laboratory measurements

A fasting blood sample was obtained from all patients on the second day of hospitalization. The levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), creatinine, low-density lipoprotein, and high-density lipoprotein were monitored. We estimated the glomerular filtration rate using the CKD-EPI equation: a × (serum creatinine/b)c × (0.993)age, where a was 144 and 141 for women and men, respectively; b was 0.7 and 0.9 for women and men, respectively; c was − 0.329 and − 1.209 if the creatinine level was < 0.7 and > 0.7 mg/dL, respectively, for women, and − 0.411 and − 1.209 if the creatinine level was < 0.7 mg/dL and > 0.7 mg/dL, respectively, for men.

Follow-up data

Clinical status of the study patients was obtained through telephone interviews at least once a year after septal myectomy. Those subjects who died were treated as the endpoints, and the follow-up time was defined as their dead time. The last follow-up of survivors was conducted in December 2018. The causes of death were sudden cardiac death (SCD), death related to congestive heart failure and other cardiovascular disease, or noncardiac death. Because there were no noncardiac deaths in these patients, the survival analysis used in the present study only included cardiovascular death and SCD.

Statistical analysis

In the present study, we performed a propensity score match for the main variables found to differ significantly (p < 0.05) according to diabetes status: age, sex, BMI, hypertension, and hyperlipemia. Matching was performed using the nearest neighbour method, assigning patients with diabetes and without diabetes in a 1:2 ratio, with a 0.2 caliper width. The equalization test after matching are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1 and Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range [IQR]), or percentage, as appropriate. Student t-test and Mann–Whitney U test for matched samples were used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare classification variables, as appropriate. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate survival free from cardiovascular death and compare SCD between the two groups. A log-rank test was used to compare survival curves between the two groups. A stepwise multiple Cox analysis technique was used to identify the variables independently associated with cardiovascular death in these patients which were incorporated into the final models. Age, sex, and variables with p < 0.1 on the univariable analysis were added to the multivariable analysis. All reported probability values were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS version 26.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used for calculations and illustrations in the present study.

Results

Preoperative and perioperative patient characteristics

A total of 201 HOCM patients (with T2DM, 67 patients; without T2DM, 134) were included. We compared the baseline characteristics between the two groups (Table 1). Compared with patients without DM, those with HOCM and DM had a lower glomerular filtration rate and hs-CRP level. There was no difference in symptoms, including chest pain, palpitation, and syncope, between the two groups. In addition, the prevalence of AF was significantly higher in patients with HOCM and T2DM than in those with HOCM alone. Of the 67 patients with T2DM, 19 (28.4%) were treated with insulin, 39 (58.2%) were treated with metformin, 9 (13.4%) patients were treated with acarbose, and 3 (4.5) patients were treated with metformin and acarbose. In addition, the baseline characteristics of patients with and without T2DM before matching are shown in Additional file 3: Table S2.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characters

| Variable | No diabetes (n = 134) | Diabetes (n = 67) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 48.8 ± 13.5 | 50.1 ± 13.8 | 0.53 |

| Male, n | 78 (58.2%) | 41 (61.2%) | 0.69 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.9 ± 3.9 | 25.6 ± 3.7 | 0.69 |

| Family history of HCM or SCD, n | 18 (13.4%) | 15 (22.4%) | 0.11 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 72.2 ± 9.3 | 72.7 ± 8.5 | 0.71 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 1379.9 (636.3–2342.4) | 1605.5 (573.7–2726.3) | 0.71 |

| Creatinine, umol/L | 77.3 ± 13.4 | 76.8 ± 14.8 | 0.83 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, ml/min | 99.8 ± 20.2 | 93.7 ± 18.5 | 0.04 |

| Hs-CRP, mg/L | 0.97 (0.40–1.80) | 1.30 (0.56–2.28) | 0.04 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0.31 |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.16 ± 0.3 | 0.63 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension, n | 54 (40.3%) | 28 (41.8%) | 0.84 |

| Hyperlipemia, n | 28 (20.9%) | 15 (22.4%) | 0.81 |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Chest pain, n | 35 (26.1%) | 20 (29.9%) | 0.58 |

| Palpitation, n | 11 (8.2%) | 8 (11.9%) | 0.39 |

| Syncope, n | 14 (10.4%) | 8 (11.9%) | 0.75 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n | 16 (11.9%) | 19 (28.4%) | 0.004 |

| Echocardiographic indices | |||

| LVEDD, mm | 41.8 ± 5.7 | 41.5 ± 4.5 | 0.70 |

| IVST, mm | 20.3 ± 5.6 | 20.0 ± 5.8 | 0.74 |

| Posterior wall, mm | 11.9 ± 2.4 | 12.2 ± 2.9 | 0.56 |

| LVEF, % | 71.4 ± 5.6 | 71.3 ± 5.4 | 0.94 |

| IVST ≥ 30 mm, n | 11 (8.2%) | 4 (6.0%) | 0.57 |

| Moderate or severe MR | 24 (17.9%) | 7 (10.4%) | 0.17 |

| Medical therapy | |||

| Beta-blockers, n | 99 (73.9%) | 50 (74.6%) | 0.91 |

| Calcium-channel blockers, n | 7 (5.2%) | 7 (10.4%) | 0.17 |

| ACEI/ARB, n | 17 (12.7%) | 8 (11.9%) | 0.88 |

| Statins, n | 14 (10.4%) | 11 (16.4%) | 0.23 |

| Insulin, n | – | 19 (28.4%) | – |

| Metformin, n | – | 39 (58.2%) | – |

| Acarbose, n | – | 12 (17.9%) | – |

Values are presented as percentage, mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range) when appropriate

IVST interventricular septal thickness, HCM hypertrophic myocardiopathy; SCD sudden cardiac death, NYHA New York Heart Association, BNP brain natriuretic peptide, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, LDL low density lipoprotein, HDL high density lipoprotein, LVEDD left ventricular end diastole diameter, LVOT left ventricular outflow tract, MR mitral regurgitation, ACEI/ARB angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker

The perioperative period was 30 days after the operation. Patients with HCM and T2DM had a higher proportion of coronary artery bypass and maze procedures. The immediate postoperative LVOT gradient was higher in patients with HCM and T2DM. Only one patient died during the perioperative period in the T2DM group (0% vs. 1.5%, p = 0.33). However, the other parameters did not differ between the two groups during the perioperative period. Detailed information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Perioperative data between two groups

| Variable | No diabetes (n = 134) | Diabetes (n = 67) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concomitant procedures | |||

| Mitral valve procedure, n | 22 (16.4%) | 9 (13.4%) | 0.58 |

| Tricuspid valvuloplasty, n | 15 (11.2%^) | 7 (10.4%) | 0.87 |

| CABG, n | 6 (4.5%) | 8 (11.9%) | 0.05 |

| Maze procedure, n | 5 (3.7%) | 8 (11.9%) | 0.03 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time, min | 107.6 ± 47.1 | 113.3 ± 51.2 | 0.43 |

| Aortic crossclamping time, min | 72.7 ± 36.4 | 76.8 ± 35.9 | 0.45 |

| Postoperative ventilation time, min | 17.0 (13.0–21.0) | 17.0 (13.0–24.0) | 0.98 |

| Postoperative hospital stays, day | 8.4 ± 3.8 | 8.4 ± 4.2 | 0.96 |

| Post-operative LVOT gradient, mmHg | 6.6 ± 2.7 | 7.6 ± 3.4 | 0.04 |

| Perioperative death | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0.33 |

Values are presented as percentage, mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range) when appropriate

CABG coronary artery bypass graft, ICU intensive care unit

CMR findings

In the present study, 150 patients underwent CMR. As shown in Table 3, the RVEF was higher in patients without T2DM, whereas the other parameters, including the percentage of LGE, did not differ between the two groups.

Table 3.

Parameters of cardiac magnetic resonance

| Variable | No diabetes (n = 98) | Diabetes (n = 52) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RVEF, % | 47.5 ± 7.8 | 43.9 ± 8.6 | 0.01 |

| Maximal ISVT, mm | 22.2 ± 5.3 | 22.1 ± 5.1 | 0.91 |

| Indexed LV mass, g/m2 | 99.1 ± 36.2 | 92.3 ± 38.1 | 0.28 |

| Indexed LV volume, ml/m2 | 93.7 ± 36.9 | 87.9 ± 36.3 | 0.29 |

| Indexed LGE mass, g/m2 | 7.3 (3.5–15.8) | 8.4 (3.9–15.6) | 0.98 |

| Indexed LGE volume, ml/m2 | 6.9 (3.3–15.1) | 8.0 (3.7–14.9) | 0.97 |

| LGE %, % of LV mass | 7.9 (4.1–17.9) | 8.3 (5.5–14.8) | 0.77 |

Values are presented as percentages, mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range), when appropriate

RVEF right ventricular ejection fraction, IVST interventricular septal thickness, LGE Late Gadolinium Enhancement

Follow-up data

The follow-up data are shown in Table 4. The percentage of New York Heart Association class III or IV did not differ between baseline and at the last follow-up. At baseline, the proportions of NSVT and left atrium diameter ≥ 45 mm were higher in patients with HOCM and T2DM. However, the prevalence of NSVT remained high in these patients after surgery, whereas left atrium diameter ≥ 45 mm had no difference after surgery. Importantly, the incidence of pulmonary hypertension did not differ preoperatively, but increased significantly during follow-up in patients with T2DM. In addition, patients with HOCM and T2DM had a higher LVOT gradient at baseline.

Table 4.

Baseline and last follow-up data

| Variables | No diabetes (n = 134) | Diabetes (n = 67) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| NYHA class III or IV, n | |||

| Baseline | 104 (77.6%) | 54 (80.6%) | 0.63 |

| Last follow-up | 6 (4.5%) | 7 (10.4%) | 0.11 |

| Pulmonary hypertension, n | |||

| Baseline | 17 (12.7%) | 5 (7.5%) | 0.26 |

| Last follow-up | 3 (2.2%) | 7 (10.4%) | 0.02 |

| NSVT, n | |||

| Baseline | 15 (11.2%) | 15 (22.4%) | 0.04 |

| Last follow-up | 2 (1.5%) | 5 (7.5%) | 0.04 |

| LVOT gradient, mmHg | |||

| Baseline | 83.3 ± 26.3 | 93.2 ± 36.8 | 0.03 |

| Last follow-up | 11.6 ± 8.4 | 12.2 ± 8.5 | 0.64 |

| Left atrium ≥ 45 mm, n | |||

| Baseline | 47 (35.1%) | 33 (49.3%) | 0.05 |

| Last follow-up | 37 (27.6%) | 17 (25.4%) | 0.74 |

| Death, n | 4 (3.0%) | 5 (7.5%) | 0.16 |

| Sudden cardiac death, n | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.5%) | 0.04 |

Values are presented as percentage, mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range) when appropriate

NYHA New York Heart Association, NSVT non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, LVOT left ventricular outflow tract, LVEDD left ventricular end diastole diameter

Outcomes and mortality

During a median follow-up of 28.0 (IQR: 13.0–53.0) months, 9 patients died. In this study cohort, the cause of death in these patients was cardiovascular death, including 3 SCD, 4 deaths related to heart failure, 1 death due to infective endocarditis, and 1 death due to myocardial infarction. Patients with diabetes had a significantly high rate of SCD (4.5% vs. 0.0%, p = 0.04). The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed no difference in the rates of predicted 3-year survival free from cardiovascular death (98.1% vs. 95.1%, p = 0.14) (Fig. 1). However, the rate of predicted 3-year survival free from SCD (100% vs 96.7%, p = 0.013) was lower in patients with HOCM and T2DM than in those without T2DM (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we analyzed the factors associated with cardiovascular death in patients with HOCM and T2DM. The univariable analysis revealed that history of NSVT (hazards ratio [HR]: 1.51, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.31–1.73, p = 0.03), glomerular filtration rate ≤ 80 ml/min (HR:4.84, 95% CI 1.42–19.36, p = 0.02), N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP; HR: 1.001, 95% CI 1.000–1.002, p = 0.002), and postoperative LVOT gradient (HR: 1.80, 95% CI 1.08–3.02, p = 0.02) were associated with cardiovascular death in this particular cohort. However, after adjustment for age, and sex, only NT-proBNP (HR: 1.002, 95% CI 1.000–1.005, p = 0.02) and the glomerular filtration rate ≤ 80 ml/min (HR: 3.23, 95% CI 1.34–7.24, p = 0.047) were independent risk factors for patients with T2DM (Table 5).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival free from cardiovascular death between two groups

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival free from SCD between two groups. SCD sudden cardiac death

Table 5.

Multivariate cox proportional Hazards Models for cardiovascular death in patients with T2DM

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age | 0.97 (0.91–1.04) | 0.38 | ||

| Male | 0.49 (0.08–2.96) | 0.44 | ||

| NT-Pro BNP | 1.001 (1.000–1.002) | 0.002 | 1.002 (1.000–1.005) | 0.02 |

| eGFR ≤ 80 ml/min | 4.83 (1.42–19.36) | 0.02 | 3.23 (1.34–7.24) | 0.04 |

| NSVT | 1.51 (1.31–1.73) | 0.03 | ||

| Post-operative LVOT gradient | 1.80 (1.08–3.02) | 0.02 | ||

HR hazards ratio, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, NSVT non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, LVOT left ventricular outflow tract gradient

Discussion

Our study investigated the impact of T2DM on the midterm mortality of HOCM patients after septal myectomy. Several findings were included in the present study. First, HOCM patients with T2DM are more likely to develop pulmonary hypertension after surgery, and they have a higher incidence of NSVT even after septal myectomy. Second, HCM patients with and without T2DM have similar 5-year cardiovascular mortality after septal myectomy, but it is associated with higher SCD rate after surgery. Lastly, the baseline NT-proBNP and glomerular filtration rate were independent risk factors among HCM patients with T2DM.

Only a few studies have been reported the impact of T2DM on the clinical outcomes of HCM patients. Recently, one study reported the impact of DM on the clinical phenotype of HCM [3]. They showed that HCM patients with diabetes have a higher cardiovascular risk profile, a lower functional capacity, and more heart failure symptoms. In addition, they found that no difference in the rates of SCD in patients with or without DM. Actually, for patients who underwent septal myectomy have a lower mortality during perioperative period or a long-term result [13, 14]. No study has reported on the influence of T2DM on HCM patients who underwent septal myectomy. However, the impact of DM on the clinical outcomes has been well studied in patients who underwent valve operations and coronary artery bypass. Many studies have reported that DM is associated with significantly worse outcomes after valve operations, and it is an independent predictor for long-term mortality after isolated aortic valve replacement [5, 7, 15]. In addition, previous studies have revealed that DM can increase the incidence of perioperative complications and heart failure and is an independent predictor of long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass [6, 16, 17].

DM can affect the cardiovascular system of HCM patients through many aspects. First, chronic inflammation and microvascular changes within the kidney caused by DM can increase serum levels of inflammatory cytokines and impairment of renal function [18, 19]. In our study, we found that the level of hs-CRP was high and the glomerular filtration rate was low in HCM patients with T2DM. Second, potential contributors of DM to the induction of cardiac arrhythmias, including hyperglycemia or glucose fluctuations and autonomic dysfunction, activate multiple mechanisms that contribute to the development of cardiac arrhythmias. In addition, structural remodeling, including changes in the electrical conduction of the heart, and fibrosis promote and potentiate the progression of arrhythmia [20]. The main finding of our study, i.e., the incidence rates of NSVT and AF were significantly higher in HOCM patients with T2DM than in those without T2DM, was consistent with those of previous studies. Both of these arrhythmias are associated with worse clinical outcomes for HOCM patients. Third, in our study, we found that the prevalence of pulmonary hypertension had no difference before operation, whereas the incidence of pulmonary hypertension after surgery increased significantly. Insulin resistance in DM patients may be a risk factor for pulmonary hypertension [21]. Moreover, in our study, we also found that RVEF was also high in HOCM patients with DM, which may reflect a decrease in right ventricular function. Lastly, the proportion of coronary artery bypass was high in HOCM patients DM. Chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia in DM can promote the development of coronary artery disease.

In our study, we found that the rates of predicted 3-year survival free from cardiovascular death are not different between HOCM patients with and without DM after septal myectomy, whereas the rate of predicted 3-year survival free from SCD was significantly lower in patients without DM than in those with DM. This is inconsistent with the previous study that HCM patients with diabetes have a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and that there was no difference in SCD between patients with and without DM. The reason for this is that none of the patients underwent septal myectomy, and most HCM patients have no LVOT obstruction in that study. The incidence of NSVT was high in HOCM patients with DM even after surgery, which is a known risk factor for SCD [22, 23]. In addition, we analyzed the variables associated with cardiovascular death in the subgroup of HOCM patients with DM. After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI, NT-proBNP and glomerular filtration rate were independent risk factors for cardiovascular death in this particular cohort. This is consistent with the previous studies that the NT-proBNP has been demonstrated as a novel marker for adverse clinical outcomes in HCM patients [24, 25]. Moreover, a previous study revealed that percutaneous transluminal septal myocardial ablation could improve the renal function of patients with HCM, which suggests that these patients may have renal dysfunction [26]. In addition, DM can affect renal function through many ways [19].

DM is the main cause of heart failure, either secondary to cardiovascular disease or secondary to diabetic cardiomyopathy. HCM patients with DM have lower functional capacity and more heart failure symptoms. Therefore, in clinical practice, careful attention should be given for these particular patients who underwent septal myectomy, and they should be need to be followed up more closely, including monitoring of the effects of diabetes on other systems. In addition, because these patients have a relatively higher rate of SCD, we believe that ICD should be implanted more actively in patients with cardiac arrhythmia. By strengthening the management of these patients, we can reduce the complications and improve the prognosis of these patients.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, this study is limited by its observational nature and the inherent limitations of a retrospective database study. Second, not all patients in our study underwent CMR, which limited our systematic analysis of myocardial fibrosis and right ventricular function in all patients. Third, although the patients in our study were from two medical centers, the number of HOCM patients with DM after septal myectomy is still small. Because of the small number of this particular cohort, we cannot analyze the difference in survival between DM patients who received medication and insulin.

Conclusions

T2DM is associated with a higher SCD rate in a matched cohort with HOCM who underwent septal myectomy. However, it has no influence on the rate of cardiovascular death of these patients. In addition, the multivariable analysis revealed that the NT-proBNP and glomerular filtration rate were independent risk factors among HOCM patients with T2DM after surgery. The results of the present study suggest that HOCM patients with T2DM should be carefully monitored, especially its effects on renal function, after surgery.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Relative multivariable imbalance L1 and Summary of unbalanced covariates.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Standardized difference before and after matching.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Baseline patient characters in unmatched cohort.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CMR

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

- CVD

Cardiovascular death

- HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- HOCM

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

- HR

Hazards ratio

- hs-CRP

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- LGE

Late gadolinium enhancement

- LV

Left ventricular

- LVOT

Left ventricular outflow tract

- NSVT

Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide

- SCD

Sudden cardiac death

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study and in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. All authors reviewed the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81570276) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81770371).

Availability of data and materials

According to the Fuwai Hospital and Anzhen Hospital system, we are not allowed to share original study data publicly. Therefore, the datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval of the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Affiliated Fuwai Hospital and Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, was obtained before the start of the work.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shuiyun Wang, Email: wsymd@sina.com.

Yongqiang Lai, Email: yongqianglai@yahoo.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12933-020-01036-1.

References

- 1.American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on P, American Association for Thoracic S, American Society of E, American Society of Nuclear C, Heart Failure Society of A, Heart Rhythm S, Society for Cardiovascular A, Interventions, Society of Thoracic S, Gersh BJ, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American college of cardiology Foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(6):e153–e203. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Authors/Task Force m. Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, Borggrefe M, Cecchi F, Charron P, Hagege AA, Lafont A, Limongelli G, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the task force for the diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2014;35(39):2733–2779. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wasserstrum Y, Barriales-Villa R, Fernández-Fernández X, Adler Y, Lotan D, Peled Y, Klempfner R, Kuperstein R, Shlomo N, Sabbag A, et al. The impact of diabetes mellitus on the clinical phenotype of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2018;40(21):1671–1677. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strain WD, Paldanius PM. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the microcirculation. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0703-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halkos ME, Kilgo P, Lattouf OM, Puskas JD, Cooper WA, Guyton RA, Thourani VH. The effect of diabetes mellitus on in-hospital and long-term outcomes after heart valve operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(1):124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kogan A, Ram E, Levin S, Fisman EZ, Tenenbaum A, Raanani E, Sternik L. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on short- and long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):151. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0796-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ram E, Kogan A, Levin S, Fisman EZ, Tenenbaum A, Raanani E, Sternik L. Type 2 diabetes mellitus increases long-term mortality risk after isolated surgical aortic valve replacement. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0836-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang S, Cui H, Yu Q, Chen H, Zhu C, Wang J, Xiao M, Zhang Y, Wu R, Hu S. Excision of anomalous muscle bundles as an important addition to extended septal myectomy for treatment of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(2):461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo HC, Wang Y, Dai J, Ren CW, Li JH, Lai YQ. Application of 3D printing in the surgical planning of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy and physician-patient communication: a preliminary study. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(2):867–873. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.01.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American society of echocardiography’s guidelines and standards committee and the chamber quantification writing group, developed in conjunction with the european association of echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green JJ, Berger JS, Kramer CM, Salerno M. Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in clinical outcomes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2012;5(4):370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabe MA, Sabe SA, Kusunose K, Flamm SD, Griffin BP, Kwon DH. Predictors and prognostic significance of right ventricular ejection fraction in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2016;134(9):656–665. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geske JB, Driver CN, Yogeswaran V, Ommen SR, Schaff HV. Comparison of expected and observed outcomes for septal myectomy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 2020;221:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai MY, Bhonsale A, Smedira NG, Naji P, Thamilarasan M, Lytle BW, Lever HM. Predictors of long-term outcomes in symptomatic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy patients undergoing surgical relief of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 2013;128(3):209–216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-de-Andrés A, de Miguel-Díez J, Muñoz-Rivas N, Hernández-Barrera V, Méndez-Bailón M, de Miguel-Yanes JM, Jiménez-García R. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the utilization and in-hospital outcomes of surgical mitral valve replacement in Spain (2001–2015) Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0866-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brush JE, Siraj ES, Kemp CD, Liverman DP, McMichael BY, Lamichhane R, Sheehan BE. Effect of diabetes mellitus on complication rates of coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124(9):1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeji Y, Shiomi H, Morimoto T, Furukawa Y, Ehara N, Nakagawa Y, Kato T, Tazaki J, Kato ET, Yaku H, et al. Diabetes mellitus and long-term risk for heart failure after coronary revascularization. Circul J. 2020;84(3):471–478. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C, Feng X, Li Q, Wang Y, Li Q, Hua M. Adiponectin, TNF-alpha and inflammatory cytokines and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cytokine. 2016;86:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anders HJ, Huber TB, Isermann B, Schiffer M. CKD in diabetes: diabetic kidney disease versus nondiabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(6):361–377. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0001-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grisanti LA. Diabetes and arrhythmias: pathophysiology, mechanisms and therapeutic outcomes. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1669. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuso L, Pitocco D, Antonelli-Incalzi R. Diabetic lung, an underrated complication from restrictive functional pattern to pulmonary hypertension. Diabetes Metabol Res Rev. 2019;35(6):e3159. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monserrat L, Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Sharma S, Penas-Lado M, McKenna WJ. Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(5):873–879. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Salvo G, Pacileo G, Limongelli G, Baldini L, Rea A, Verrengia M, D’Andrea A, Russo MG, Calabro R. Non sustained ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and new ultrasonic derived parameters. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(6):581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coats CJ, Gallagher MJ, Foley M, O’Mahony C, Critoph C, Gimeno J, Dawnay A, McKenna WJ, Elliott PM. Relation between serum N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and prognosis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(32):2529–2537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song C, Wang S, Guo Y, Zheng X, Lu J, Fang X, Wang S, Huang X. Preoperative NT-proBNP predicts midterm outcome after septal myectomy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(4):e011075. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maekawa Y, Jinzaki M, Tsuruta H, Akita K, Yamada Y, Kawakami T, Hayashida K, Yuasa S, Murata M, Fukuda K. Improved renal function in a patient with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy after multidetector computed tomography-guided percutaneous transluminal septal myocardial ablation. Int J Cardiol. 2015;181:349–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Relative multivariable imbalance L1 and Summary of unbalanced covariates.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Standardized difference before and after matching.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Baseline patient characters in unmatched cohort.

Data Availability Statement

According to the Fuwai Hospital and Anzhen Hospital system, we are not allowed to share original study data publicly. Therefore, the datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available.