Abstract

To generate a Hospital Medical Surge Preparedness Index that can be used to evaluate hospitals across the United States in regard to their capacity to handle patient surges during mass casualty events. Data from the American Hospital Association’s annual survey, conducted from 2005 to 2014. Our sample comprised 6239 hospitals across all 50 states, with an annual average of 5769 admissions. An extensive review of the American Hospital Association survey was conducted and relevant variables applicable to hospital inpatient services were extracted. Subject matter experts then categorized these items according to the following subdomains of the “Science of Surge” construct: staff, supplies, space, and system. The variables within these categories were then analyzed through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, concluding with the evaluation of internal reliability. Based on the combined results, we generated individual (by hospital) scores for each of the four metrics and an overall score. The exploratory factor analysis indicated a clustering of variables consistent with the “Science of Surge” subdomains, and this finding was in agreement with the statistics generated through the confirmatory factor analysis. We also found high internal reliability coefficients, with Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs exceeding 0.9. A novel Hospital Medical Surge Preparedness Index linked to hospital metrics has been developed to assess a health care facility’s capacity to manage patients from mass casualty events. This index could be used by hospitals and emergency management planners to assess a facility’s readiness to provide care during disasters.

Keywords: Health care utilization, Mass casualty events, Medical surge, Preparedness index, Factor analyses

Introduction

Recent mass casualty events in the United States have directed a spotlight on the need for efficient and effective medical responses to sudden influxes of injured and ill people. One example is the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, which resulted in more than 250 individuals requiring immediate care at local hospitals (Hanfling 2014). Less than 5 years later, on October 1, 2017, a single gunman in Las Vegas sent more than 500 concert-goers to local hospitals, constituting a trauma event of historic proportions (Mass Shootings 2018). These events arise in the context of Federal Bureau of Investigation data indicating that the incidence of mass casualty events (defined as events in which three or more people are killed or injured) is increasing in the United States (FBI 2013). Such events place significant strains on health systems to effectively manage an acute influx of casualties, classically known as medical surge (HHS 2012).

In its entirety, medical surge invokes response across a variety of community resources, including: law enforcement, emergency medical services (EMS), fire departments, health care providers, public health professionals, hospital administrators, elected officials, and insurers (IOM 2007). However, hospitals serve as the epicenter for emergent health care delivery (AHA 2014) and are therefore the fulcrum for medical surge. Emergency departments (EDs) bear particular responsibility and pressure in these circumstances, as they are required to function above their originally designed capacity (Kaji et al. 2007). Mass casualty events exacerbate hospital crowding and ED admissions, disrupt normal flow of care, and strain resources and logistics, all potentially contributing to compromised quality and safety of patient care (IOM 2007). During such emergencies, “hospitals are expected to function independently for as long as 96 hours” (Kelen et al. 2017), and their level of readiness plays a pivotal role in determining victims’ outcomes. Hospitals must be able to medically surge, shifting to a sufficiency-of-care model aimed at saving as many lives as possible rather than delivering the usual standard of care (IOM 2012). This concept is well described in the Institute of Medicine work titled Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response (2012). As noted by Heidaranlu et al. (2017), achievement of optimal hospital disaster response depends on effective management of these events. The challenge to hospitals can be daunting.

Chief among the challenges facing hospital management in mass casualty preparedness is the absence of distinct tools for measuring readiness. Medical surge capacity is defined as a “measurable representation of a health care system’s ability to manage a sudden or rapidly progressive influx of patients within currently available resources at a given point in time” (ACEP 2012; Asplin et al. 2006; Stratton and Tyler 2006; Watson et al. 2013). Meaningful measurements, however, are neither well defined nor operational. Theoretical constructs help define medical surge capacity with more granularity, with one widely accepted construct describing four domains of surge capacity: staff, systems, supplies, and space (McCarthy et al. 2006; Kelen and McCarthy 2006). Such theory is a practical movement toward “a parsimonious set of measures to assess and improve the level of preparedness” (Marcozzi and Lurie 2012) and to assess hospitals’ ability to handle catastrophic surge events (Simiyu et al. 2014). However, this paradigm does not allow quantifiable measurement of progress. In fact, no broadly applicable index or scoring algorithm exists to evaluate hospitals’ readiness for a sudden influx of patients and their capability to render care and manage consequences across the broad range of hazard scenarios.

Currently available “measures” of healthcare facility surge capacity are not standardized, generalizable, or quantifiable. For example, Joint Commission assessments rely heavily on subjective appraisals of facility plans and procedures. The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) within the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services developed and made publicly available a Hospital Surge Evaluation tool that guide participants through a scripted exercise of emergency department triage and hospital disposition of patients from a bomb blast scenario (ASPR 2017). While generally useful, this tool does not assess capability beyond the immediate triage and patient movement aspect of the scenario, nor does it provide insight into surge capacity for a broader range of scenarios and over the duration of an event. Although the tool provides information on exercise performance, the results depend significantly on the personnel chosen to run and score the exercise and the decisions made within the scenario context. Therefore, this cannot be considered an objective or reproducible score. A similar Health Care Coalition Surge Test provides an exercise assessment for patient movement within multiple healthcare facilities in a coalition, but again, it is restricted in scope to only hospital evacuation and patient movement (ASPR 2018). A small number of investigations have attempted to apply discrete measures on hospital preparedness, including an examination of US Veterans Administration hospitals by Dobalian et al. (2016) and application of the World Health Organization (WHO) Hospital Safety Index to examine hospital preparedness in Iran and Sweden (Djalali et al. 2013).

Sustainable financial investment in any activity requires objective measures to quantify inherent risks and expected return on investment. If we expect continued or increased public sector and healthcare industry investment in healthcare system preparedness, we must do better than the status quo. Hospital leaders and national policy makers require a validated index of hospital surge preparedness to ensure health systems are capable of providing life-saving health care during disasters and guide future investment into this capability from the public and private sectors. As the saying goes, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.”

In this article, we present a Hospital Medical Surge Preparedness Index (HMSPI) that can be used to systematically evaluate health care facilities across the United States in regard to their capacity to handle patient surges during disasters. If validated, such an index would help ensure the US health care delivery system is poised to respond to mass casualty events by assessing the ability of victims to access health care (Kaji et al. 2007) as well as resolving weaknesses and reinforcing strengths in hospital and emergency management planning and capacity (Simiyu et al. 2014).

Theoretical background

The HMSPI is based on the theoretical framework proposed in Kelen and McCarthy’s seminal paper, “The Science of Surge” (2006). Their paper described four domains of surge capacity—staff, supplies, space, and system—and their subcomponents (Table 1). For our purposes, we kept the primary metrics but considered the subcomponents in greater depth using information from the AHA database. The four domains are defined as follows: (1) Staff refers to personnel such as nurses, physicians, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and technicians as well as non-medical personnel who are necessary for the efficient functioning of a health care facility or entity, including clerical support personnel, security specialists, and physical plant specialists. (2) Supplies include durable equipment, such as cardiac monitors, defibrillators, intravenous (IV) pumps, ventilators, blood glucose monitors, and laboratory equipment. Supplies also include consumable materials such as medications, oxygen, sterile dressings, intravenous fluids, IV catheters, syringes, sutures, and personal protective equipment. (3) Space includes total beds, staffed beds (beds available for which staff is able to attend to), available spaces and other opportunities to house patients, and the percentage of beds occupied. (4) Systems for health care organizations include integrated policies and procedures that operationally and financially link multiple hospitals and individual departments within a health care setting. Additionally, systems can refer to policies and procedures that link a given health care facility with other health care entities such as EMS, home health care, long-term care, and physicians’ offices.

Table 1.

Components of catastrophic event surge.

From Kelen and McCarthy (2006). Used with permission

| System | Space | Staff | Supplies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning | Facilities | Numbers | Biologics |

| Community infrastructure | Medical care | Capability/skill set | Respirators |

| Government | Storage | Expertise | Personal protective equipment |

| Informal networks | Laboratory | Stamina | Standard supplies |

| Public health | Mortuary | Psych | Food and water |

| Incident command | Housing of staff | ||

| All levels | |||

| HEIC | Quality | ||

| Regional cooperation | Size | ||

| Multiagency | Capacity | ||

| Regional health system | Location | ||

| Communications and information flow | |||

| Supply chain distribution | |||

| EMS/first responders | |||

| Continuity of operations | |||

| Cybersecurity |

HEIC hospital epidemiology and infection control

Methods

Study design

We used the 2014 survey (most recently available) conducted by the American Hospital Association (AHA) (2018) (see below) to develop a novel index to measure hospital and regional capacity for surge in response to mass casualty events. Construction of the index began by assigning AHA survey variables related to inpatient services to the four categories described in “The Science of Surge” (Kelen and McCarthy 2006). Inpatient variables were selected because they are associated primarily with a hospital’s surge readiness to mass casualty events. The AHA variables were selected by an investigative team assembled by the authors of this paper, whose members have extensive expertise in health care delivery, specifically during times of crisis.

The variable assignment process employed a modified Delphi process with rounds of individual scoring and group discussion. After review, each of the applicable variables in the AHA database was classified within one of the four “categories” in the “The Science of Surge”. Generally, the ‘staff’ category represented numbers, skill set and expertise of staff. Specifically, the ‘staff category’ included AHA survey variables related to medical personnel, technicians, therapists, and non-medical personnel necessary for the efficient functioning of a health care facility or entity, including case management. Relating the AHA data set to Kelen and McCarthy’s ‘supplies’ variables correlated with: supplies directly purchased through a distributor, the number of computed-tomography (CT) scanners and total costs attributed to equipment. ‘Space’ subcomponents included hospital bed quality, size and location. This corresponded to variables within the AHA survey including licensed beds per facility, total gross square feet, burn care beds, and total staffed beds. Finally, the ‘system’ category contained components aligned with AHA survey items such as: whether the institution was part of a preferred provider organization or if the hospital participated in any joint venture arrangements with physicians. When disagreement occurred among our reviewers in relation to variable assignment, an evidence-based review was conducted with a discussion resulting in consensus. Item assignments within the four categories were then evaluated using a series of psychometric tests. After variable-category assignments were competed, external emergency management subject matter experts at the local, city, and federal levels independently reviewed the category-variable assignments for agreement.

Ethics

The institutional review board at the academic medical center with which the lead author is affiliated has approved this study.

Setting and hospitals

The AHA annual survey creates a comprehensive database for the analysis and comparison of health care industry trends among all types of hospitals, health care systems, networks, and other providers of care in the United States. Registered hospitals consist of AHA member hospitals as well as nonmember hospitals. Community hospitals include all non-federal, short-term general and specialty hospitals as well as non-federal, short-term academic medical centers and other teaching hospitals. Health systems include either a multi-hospital system defined by two or more hospitals owned, leased, sponsored, or contract managed by a central organization or a diversified single hospital system. A health system can be a multi-hospital system, that is, two or more hospitals owned, leased, sponsored, or contract managed by a central organization, or a diversified single hospital system. In this study, we conducted our analysis based on hospitals only rather than aggregating them into systems or networks. The AHA database allows analysis of trends in utilization, personnel, revenues, and expenses across local, regional, and national markets. It contains more than 1000 data fields from over 6300 hospitals. The survey has a response rate above 75%. To address non-response and to complete missing data within the AHA survey, a standardized imputation methodology was employed based on previous responses. The AHA database contains information about hospital demographics, organizational structure, service lines and facilities, utilization data, physician arrangements, managed care relationships, hospital expenses, and staffing. For our analysis, we included all registered community-based hospitals in the United States, both for-profit and non-for-profit, that were operating in 2014.

Sample descriptive statistics

Our analysis began with a visual exploration of all variables to evaluate the frequency, percentage, and near-zero variance for categorical variables (e.g., hospital participation in a network, presence of an electronic health record, participation in a bundled payment program). We also assessed distributions for numeric variables (e.g., the number of nurses, physicians, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and technicians and their corresponding missing value patterns) (Kuhn and Johnson 2013). Near-zero variance was addressed by either combining categories or deleting the variable. Missing values were handled by applying the original AHA imputation algorithms (2018). We used the median number of hospital beds to stratify the overall sample. To evaluate statistical differences between groups, we used t tests and one-way ANOVA for numeric variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables.

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses

To further examine variable distributions and associations, we generated a correlation matrix plot followed by an exploratory factor analysis (Revelle 2017). Since items were ordinal and logical, we used polychoric and polyserial correlation tests as appropriate. We also conducted a series of exploratory factor analyses using a matrix correlation containing all variables described under Table 1. Oblique and orthogonal rotations were used to explore different factorial solutions underlying the data, using maximum likelihood as the extraction method. Our heuristic for the selection of factor solutions included scree plots, solutions that were theoretically justifiable, and solutions in which items loaded with values above 0.30 on a single factor while all other loadings were below that level.

A confirmatory factor analysis was then conducted, using the theoretical framework proposed by Kelen and McCarthy (2006) and a bi-factor model (Beaujean 2014). The hierarchical model assumed four different metrics (staff, supplies, space, systems) along with an overarching surge construct. Fit statistics for confirmatory factor analyses included a Relative Fit Index, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual, and Parsimony Goodness-of-Fit Index. Based on the combined results from the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, we generated individual (by hospital) scores for each of the four metrics and an overall HMSPI score. Scores were normalized at the item and sub-domain levels.

Internal reliability

Normalized scores, which ranged from 0 to 100, were used for reliability assessment through Cronbach’s alpha and omega (Dunn et al. 2014) within each factor (Revelle 2017). Scores were normalized for each item, then each metric (systems, staff, supplies, and space), and then the overall surge score, using a standard formula:

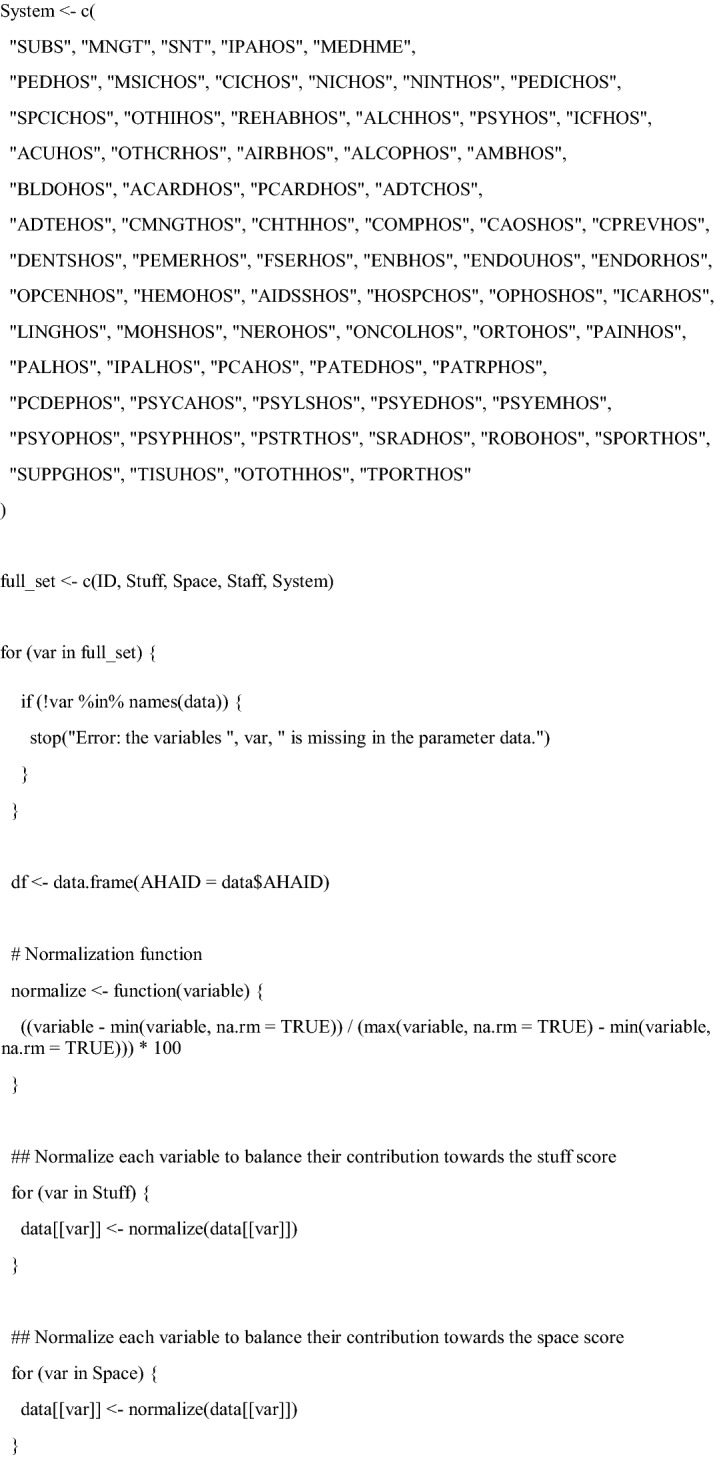

Since no maximum upper values exist for numeric variables, we normalized the score for the maximum value of each variable to the year 2014 (“Appendix”, Surge Index Function).

Results

Hospital sample

Table 2 displays the overall sample stratified by the median number of hospital staffed beds, with numeric variables compared through t tests and one-way ANOVA tests; categorical variables are compared via chi-squared tests. Our sample consisted of 6239 hospitals divided into two groups: 3123 with 82 beds or fewer and 3116 with more than 82 beds. As expected, the group with more than 82 staffed beds had a significantly higher value for all metrics evaluated, including total facility admissions, surgical operations, emergency department visits, operating rooms, adult and pediatric beds, neonatal and ICU (intensive care unit) beds, and burn beds.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics stratified by median number of hospital beds

| Variable [Missing] | Total hospitals (6239) | Hospitals with ≤ 82 beds (3123) | Hospitals > 82 beds (3116) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total facility admissions [0] | 5769 (± 8685) | 1029 (± 962) | 10,521 (± 10,247) | < 0.001 |

| Total surgical operations [0] | 4517 (± 7129) | 1229 (± 1788) | 7813 (± 8768) | < 0.001 |

| Emergency room visits [0] | 22,898 (± 31,046) | 6675 (± 8437) | 39,158 (± 36,477) | < 0.001 |

| Number of operating rooms [1809] | 7.85 (± 10.7) | 2.34 (± 2.63) | 12.8 (± 12.6) | < 0.001 |

| General medical and surgical (adult) beds [1617] | 77 (± 104) | 18.8 (± 14.6) | 131 (± 120) | < 0.001 |

| General medical and surgical (pediatric) beds [1617] | 5.81 (± 19.7) | 0.71 (± 4.06) | 10.5 (± 26.2) | < 0.001 |

| Neonatal intermediate care beds [1617] | 1.52 (± 6.29) | 0.0374 (± 0.52) | 2.89 (± 8.49) | < 0.001 |

| Pediatric intensive care beds [1617] | 1.01 (± 4.94) | 0.0252 (± 0.55) | 1.93 (± 6.71) | < 0.001 |

| Burn care beds [1617] | 0.24 (± 1.84) | 0.0149 (± 0.5) | 0.46 (± 2.5) | < 0.001 |

Correlation matrices

Our evaluation of the AHA variables started with the complete list of survey factors hypothesized to be associated with the four domains (see “Appendix”). We used correlation matrices to explore the association of variables within each of the four metrics.

Figure 1 presents a correlation matrix of hospital variables related to the “supplies” construct. Sub-constructs are represented by colors and include the following variables: computed tomography (CT) scanner, ultrasound, MRI, multi-slice CT 64 + and < 64 slice, PET, and electron-beam CT.

Fig. 1.

Correlation matrix demonstrating the clustering of variables representing hospitals, health systems, and networks

Exploratory factor analysis

We conducted an exploratory factor analysis to identify which variables loaded into the four metrics delineated by Kelen and McCarthy (2006). Our base criterion was that each variable should have a factor of at least 0.3 to be considered as loading onto that domain. Table 3 summarizes factors loaded for the space metric: “total facility beds,” with 0.9738 factor loading; “total hospital beds,” 0.9737; and “total facility admission,” 0.9729. Figure 2 summarizes factors loaded for the supplies metric; the same items presented a loading pattern as in Fig. 1. Item loadings for the systems and staff domains are presented in Tables 6 and 7 in the “Appendix”. For example, items such as “oncology services” (factor loading of 0.8862), “neurological services” (0.8733), and “endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography” (ERCP) (0.8613) were associated with the systems construct, whereas the staff construct was associated with “full-time equivalent (FTE) hospital unit total personnel” (0.9778), “FTE total personnel” (0.9777), and “total facility FTE personnel” (0.9733).

Table 3.

Summary of factor loadings for the space construct

| Space items | Factor loadings |

|---|---|

| Total facility bedsa | 0.9738 |

| Total hospital beds | 0.9737 |

| Total facility admission | 0.9729 |

| Total facility inpatient days | 0.9660 |

| Average daily census | 0.9660 |

| Adjusted patient days | 0.9629 |

| Adjusted average daily census | 0.9629 |

| Adjusted admission | 0.9622 |

| Licensed beds, total facility | 0.9509 |

| Number of operating rooms | 0.9079 |

| General medicine, surgery beds | 0.9073 |

| Med/surgery intensive care beds | 0.8364 |

| Airbroom | 0.8108 |

| Total square feet, physical plant | 0.7860 |

| Obstetric care beds | 0.7537 |

| Total outpatient visits | 0.7491 |

| Bassinet set up | 0.7247 |

| Other outpatient visits | 0.6853 |

a“Total facility beds” differs from “total hospital beds” because sites such as ambulatory care facilities are included

Fig. 2.

Exploratory factor analysis for the supplies construct

Table 6.

Factor loadings for the supplies construct

| Construct | Factor loadings |

|---|---|

| Full time equivalent hosp unit total personnel | 0.9778 |

| FTE total personnel | 0.9777 |

| Total facility personnel FTE | 0.9733 |

| Registered nurses FTE | 0.9676 |

| Full time equivalent registered nurses | 0.9659 |

| Full-time total personnel | 0.9633 |

| Total full-time hospital unit personnel | 0.9633 |

| Full time eq. all other personnel | 0.963 |

| Full-time registered nurses | 0.9359 |

| All other personnel FTE | 0.9322 |

| Total facility payroll expenses | 0.9321 |

| Full-time all other personnel | 0.9264 |

| Full-time pharmacists licensed | 0.904 |

| Full-time pharmacy technicians | 0.891 |

| Full-time radiology technicians | 0.8838 |

| Full-time respiratory therapists | 0.8487 |

| Respiratory therapists FTE | 0.8454 |

| Total part-time hospital unit personnel | 0.8397 |

| Part-time total personnel | 0.8384 |

| Total—total privileged | 0.8332 |

| Pharmacists licensed FTE | 0.825 |

| Nursing assistive personnel FTE | 0.8243e |

| Part-time registered nurses | 0.8129 |

| Full-time lab techs | 0.8117 |

| Lab techs FTE | 0.8102 |

| Other specialist—total privileged | 0.8035 |

| Full-time nursing assistive personnel | 0.7871 |

| Part-time all other personnel | 0.7791 |

| Full time equivalent medical and dental residents and interns | 0.7332 |

| Full-time medical and dental residents and interns | 0.7294 |

| Part-time radiology technicians | 0.7176 |

| Primary care (gen practitioner, gen int med, fam prac, gen ped, ob/gyn, geriatrics)—total privileged | 0.713 |

| Part-time nursing assistive personnel | 0.7117 |

| Part-time pharmacists licensed | 0.7007 |

| Part-time pharmacy technicians | 0.6781 |

| Radiologists/pathologist/anesthesiologist—total privileged | 0.673 |

| Total—total employed | 0.6683 |

| Part-time lab techs | 0.6474 |

| Emergency medicine—total privileged | 0.6439 |

| Other specialists—total employed | 0.6407 |

| Part-time respiratory therapists | 0.6302 |

| Hospitalist—total privileged | 0.6252 |

| Primary care (gen practitioner, gen int med, fam prac, gen ped, ob/gyn, geriatrics)—total employed | 0.5608 |

| Primary care (gen practitioner, gen int med, fam prac, gen ped, ob/gyn, geriatrics)—not employed or under contract | 0.4986 |

| Radiologists/pathologist/anesthesiologist—total employed | 0.4912 |

| Total—total group contract | 0.4177 |

| Full time eq. other trainees | 0.3989 |

| Radiologists/pathologist/anesthesiologist—total group contract | 0.3525 |

| Full-time other trainees | 0.3499 |

Table 7.

Factor loadings for the systems construct

| Construct | Factor loadings |

|---|---|

| Oncology svcs—hosp | 0.8862 |

| Neurological svcs—hosp | 0.8733 |

| ERCP—hosp | 0.8613 |

| Adult cardiac electrophysiology—hosp | 0.8591 |

| Adult cardiology svcs—hosp | 0.8387 |

| Chemo—hosp | 0.8377 |

| Adult cardiac surgery—hosp | 0.8372 |

| Robotic surgery—hosp | 0.8342 |

| Ortho svcs—hosp | 0.8307 |

| HIV-AIDS svcs—hosp | 0.8265 |

| Palliative Care prog—hosp | 0.8126 |

| Cardiac IC—hosp | 0.7926 |

| Neonatal IC—hosp | 0.7926 |

| Med/Surg IC—hosp | 0.7905 |

| SRS—hosp | 0.7846 |

| Psych consultation/liaison svcs—hosp | 0.7575 |

| Ped cardiology svcs—hosp | 0.7540 |

| Endoscopic ultrasound—hosp | 0.7540 |

| Hemodialysis—hosp | 0.7435 |

| Enabling svcs—hosp | 0.7385 |

| pnt representative svcs—hosp | 0.7376 |

| Freestanding outpnt center—hosp | 0.7366 |

| Support groups—hosp | 0.7364 |

| Other trans—hosp | 0.7308 |

| pnt education center—hosp | 0.7307 |

| Crisis prevention—hosp | 0.7283 |

| Psych emergency svcs—hosp C.82.d | 0.7268 |

| Tissue trans—hosp | 0.7265 |

| Ped IC—hosp | 0.7248 |

| pnt Controlled Analgesia—hosp | 0.7155 |

| Pain Mgmt prog—hosp | 0.7126 |

| CA ortho surg—hosp | 0.7068 |

| Complementary and alternative medicine svcs—hosp | 0.6846 |

| Mobile hsd svcs—hosp | 0.6719 |

| hosp-based outpnt care center/svcs—hosp | 0.6593 |

| Neonatal intermediate care—hosp | 0.6566 |

| Indigent care clinic—hosp | 0.6488 |

| Blood Donor Center—hosp | 0.6487 |

| Dental svcs—hosp | 0.6399 |

| Psych education svcs—hosp | 0.6359 |

| Case Mgmt—hosp | 0.6300 |

| Sports med—hosp | 0.6184 |

| Inpnt palliative care unit—hosp | 0.6172 |

| Psych outpnt svcs—hosp | 0.6081 |

| Does your hosp have an established medical home prog? | 0.6069 |

| Does your hosp provide svcs through one or more satellite facilities? | 0.6017 |

| Airborne infection isolation room—hosp | 0.6012 |

| Linguistic/translation svcs—hosp | 0.5955 |

| Other special care—hosp | 0.5801 |

| Gen med and surg care (Ped)—hosp | 0.5794 |

| ROH/drug ab or dependency outpnt svcs—hosp | 0.5727 |

| Ped ED.—hosp | 0.5420 |

| PC dept—hosp | 0.5390 |

| Psych care—hosp | 0.5390 |

| Psych partial hospitalization prog—hosp | 0.5294 |

| Does the hosp itself operate subsidiary corporations? | 0.5127 |

| Other IC—hosp | 0.5111 |

| Psych child/adolescent svcs—hosp | 0.5065 |

| Hospice prog—hosp | 0.4830 |

| Freestanding/Satellite ED.—hosp | 0.4495 |

| Phy rehab care—hosp | 0.4546 |

| Tsa to hsd svcs—hosp | 0.4014 |

| ROH/drug ab or dependency inpnt care—hosp | 0.3601 |

| Ambulance svcs—hosp | 0.2625 |

| Other care—hosp | 0.3462 |

| Psych residential treatment—hosp | 0.2200 |

| Independent practice association—hosp | 0.1163 |

| Intermediate nursing care—hosp | 0.0397 |

| Acute long-term care—hosp | − 0.2425 |

Internal reliability

Internal reliability, which indicates whether items measuring a given construct generate similar scores, is presented in Table 4. All metrics produced high internal reliability according to the classification by Nunnally (26) (i.e., all values exceeded 0.9).

Table 4.

Internal reliability for the four constructs

| Construct | Raw Alpha | Standardized Alpha | Guttman’s Lambda 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space | 0.984 | 0.984 | 0.994 |

| Staff | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.999 |

| Supplies | 0.909 | 0.909 | 1 |

| System | 0.978 | 0.978 | 1 |

| Total surge index | 0.993 | 0.993 | 1 |

Confirmatory factor analysis

Finally, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate the overall model fit. Fit statistics along with parameters for their interpretation are presented in Table 5, indicating that our confirmatory model presented an excellent fit vis-à-vis the theoretical model. Considering all four constructs, staff, supply, and system presented an adequate fit as measured through the relative fit index, with all indices reaching values close to 1.0.

Table 5.

Fit statistics with parameters

| Fit statistic | Space | Staff | Supply | System | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Fit Index | 0.568 | 1 | 0.988 | 0.951 | Values closer to 1.0 indicate better fit |

| Standardized root mean square residual | 0.086 | 0.080 | 0.094 | 0.111 | Values closer to 0.0 indicate better fit |

| Parsimony Goodness-of-Fit Index | 0.299 | 0.46 | 0.595 | 0.902 | Values closer to 1.0 indicate better fit |

The full list of variables included in the final surge index is presented as a supplementary file in the “Appendix”. The review by external emergency management subject matter experts found a 97.56% agreement with category-variable assignments.

Discussion

Despite the federal government’s investment of more than $5 billion since 2004 to ready our nation’s hospitals for disasters and mass casualties (bParati 2017), significant challenges remain. In our proposed methodology, we take an initial step toward narrowing current measurement shortcomings by advancing the science of health care preparedness through the lens of daily health care delivery, developing a standardized medical surge index. The methodology described in this manuscript addresses two challenges: (1) the divide between priorities that shape daily hospital operations and tenets of hospital readiness and (2) the lack of an objective, transparent score to assess medical surge capacity at the hospital level. Lack of standardized and systematic metrics in these areas impacts our ability to accurately assess, plan, and finance optimal health care delivery during disasters. The disconnect between daily or routine health care and care during disasters is understandable, as health care executives and disaster planners often have very different priorities as a result of conflicting economic influences. Excess capacity, which is crucial to disaster planning, is simply not a financially profitable endeavor (Marcozzi 2018). Through an objectively quantified and systematically implemented medical surge index at the hospital level, decision-makers (hospitals, planners, providers, payers, policy makers) would transparently understand the implications of policies and their effect on hospital readiness.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to empirically develop and rigorously evaluate an index that assesses the preparedness of US hospitals to provide surge care during crises. Although we recognize that health care preparedness requires contributions from many regional health care assets, including EMS and public health (ASPR 2016), our methodology examines medical surge at the hospital level, as many types of disasters are inherently inpatient events. The index is based on hospital survey data. Our exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were based on the four metrics delineated by Kelen and McCarthy (2006): systems, staff, space, and supplies. Each of these metrics was found to have high internal reliability. This approach facilitated the development of a targeted, facility-based score, synergistic with payment mechanisms (Medicare 2018) and minimizing complexities associated with regional responses.

Several previous published reports have developed evaluation metrics for hospital preparedness. Dobalian et al. (2016) created a quantified disaster preparedness scale by analyzing all 140 Veteran Affairs Medical Centers in the United States. Their analysis relied on six “mission areas” believed to represent emergency readiness but did not focus on access to care during large-scale emergencies. Medical surge was only one of these six, accounting for 12% of the total items included in the analysis. Kaji and Lewis (2008) designed a 79-item Johns Hopkins/AHRQ Hospital Disaster Drill Evaluation Tool that is used to assess hospital performance during disaster drills. This module-based tool encompasses four hospital areas: triage, incident command, decontamination, and treatment. It assigns scores based on questionnaire responses reflecting the ability to deliver medical care in times of crisis. Both of these studies evaluated the broader and less specific concept of disaster preparedness rather than surge capacity (Kaji and Lewis 2008). Unlike our index, they did not base analysis of medical surge on a previously existing theoretical framework.

Perhaps the most extensive global evaluation of hospital preparedness was published by Rockenschaub and Harbou (2013), utilizing the Hospital Safety Index developed by the World Health Organization (WHO). In applying this index, 145 items were evaluated to generate a score ranging from 0 to 1. From these scores, the authors defined thousands of hospitals reflecting their likelihood to retain functionality during disasters. The WHO Hospital Safety Index has been used extensively across several continents (Heidaranlu et al. 2017; Rockenschaub and Harbou 2013; Norman et al. 2012; Djalali et al. 2014). However, it is limited in that it is not focused on evaluating hospital surge preparedness and it contains items that are not applicable to every hospital.

The impact of medical surge events on hospital and patient outcomes has been more extensively studied. Jenkins et al. (2015) published a Trauma Surge Index that quantified the degree of strain placed on hospitals by a mass casualty event and showed a direct correlation with risk-adjusted mortality. A study by Abiland and colleagues in 2012 demonstrated that, when controlling for injury severity, patients receiving care after a mass casualty have a higher length of stay as well as inpatient costs compared with a reference cohort from before the event (Abir et al. 2012). In 2013, Rubinson et al. (2013) evaluated the effects of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic on community hospitals, finding an 18% increase in ED visits nationwide and a surge in admissions for a number of hospitals. They were able to link the surge admission rate with an increase in myocardial infarction and stroke mortality. Future combination of such functional measurements of hospital response with the HMSPI might provide additional validation and foster insight into preparedness priorities.

Our approach is consistent with previously published federal guidelines and measure development. The Agency for Health Care Research and Quality describes health care quality measures as either structure, process, or outcome based (2011). In its 2013 Hospital Preparedness Program Measure Manual (2018), ASPR described a process-based measure known as Immediate Bed Availability (IBA). IBA places quantifiable, time-based criteria on a health care community (coalition), with the focus of creating 20% additional hospital inpatient capacity within 4 h. The HMSPI is a structure-based measure, qualifying a hospital’s capacity to provide care during disasters. Combined, these two measures begin to better define the type of assessments and further refinement needed to understand hospital and regional readiness.

We believe our HMSPI could be an important addition to institutional and regional preparedness by providing individual hospitals and emergency management planners with more precise and easily understood metrics to assess their capability to respond to a mass casualty event. It is also intended to identify strengths and deficiencies in their own hospital readiness related to staffing, supplies, space and systems. Accordingly, these scores could also be used to establish synergies between hospitals to improve their collective response to a regional event. Regional and state emergency planners could utilize the HMPSI to evaluate regional and state preparedness at a population level through a composite score that encompasses all hospitals within a region or state. As depicted in Kelen and McCarthy’s work, systems (i.e., policies and procedures) are a key component of surge capacity (2006). To meet the policy goals of recent federal health care legislation and remain financially solvent, many hospitals are emphasizing population health initiatives. A potential downside of this approach is that it may result in fewer resources of staff, space, and supplies within the inpatient setting. The HMSPI could allow a more granular examination about how such trends could impact local and regional preparedness and guide planning.

Ultimately, disaster preparedness will constitute a priority for hospitals and health systems only if it impacts financial health. If incentives and market forces for hospital systems included preparedness measures, a stronger business case for disaster readiness would occur. More recently, and consistent with the concept of measure development for health care and potential economic incentives, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Preparedness and Response entered a new partnership with the National Quality Forum (NQF). We are hopeful that the methodology published here will prove valuable to that work, as existing quality measures or measure concepts that focus on the readiness of hospitals, health care systems, and communities are examined (2018). Establishing a hospital performance score that quantifies medical surge preparedness enables health care providers, hospital administrators, public health officials, and policy makers to identify and address existing gaps, incentivize improvements, and mobilize resources to mitigate weaknesses (Djalali et al. 2014). Through the use of this methodology, closer synergy between daily hospital operations and health care preparedness could be realized.

Our study has several limitations that should be noted. First, despite our best efforts to address missing data, some of our variables suffer from missing information. To minimize this limitation, we used imputation algorithms as originally applied by the AHA. Second, as health care delivery models continue to evolve, new technologies (e.g., telemedicine) may aid a hospital’s surge capacity in the face of disasters. The effect of these new technologies may require revision and updating of the AHA database to include these as variables within the four domains. Third, we did not assess external validity for the HMSPI, which would require external measurement of how hospitals and regions with different scores react during actual mass casualty incidents involving a sudden and significant demand for medical surge. Finally, although this methodology included over 1000 items from the AHA annual survey data set, it does not necessarily account for every important factor a hospital may consider when responding to a mass casualty event.

Conclusion

Linking the metrics of daily health care delivery with the ability to care for victims of tragedy is a needed evolution to better understand hospital preparedness. This study is an important step to advance the science of healthcare preparedness and we encourage future work to investigate the validity of this index with respect to outcome metrics such as mortality rates and other hospital process measures. We also recommend that our Hospital Medical Surge Preparedness Index methodology be used nationally to assess hospitals’ capacity to manage a sudden influx of patients from mass casualty events. Additionally, the HMSPI could be used to assess the impact on hospital preparedness from changes in national, state, and local health policy. Finally, linking the index to other economic and health variables would be valuable. For instance, correlating this index with a hospital’s payer mix or the surrounding community’s burden of disease, injury or risk factors could help quantify their impact on a hospital’s readiness. Further work is needed in this area, as disasters unfortunately continue to occur. Improvement in hospitals’ readiness for mass casualty events has a direct impact on a patient’s survival, a community’s well-being, and national resilience.

Acknowledgements

For their contribution to this manuscript, the authors would like to thank James Chang, BS, MS, CIH, Director of Safety and Environmental Health, University of Maryland Medical Center; James Robinson MA, Paramedic, Senior Director, Resident Risk Management, Spectrum Retirement Communities, Denver, Colorado; and, John Juskie, Director, Office of Emergency Management, U.S Department of the Interior.

Appendix

See Figs. 1 and 2 and Table 6.

Surge Index Function to generate normalized score

See Table 7.

Funding

This study was funded by the Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense and the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

David Marcozzi declares that he has no conflict of interest. Ricardo Pietrobon declares that he has no conflict of interest. James V. Lawler declares that he has no conflict of interest. Michael T. French declares that he has no conflict of interest. Carter Mecher declares that he has no conflict of interest. John Peffer declares that he has no conflict of interest. Nicole E. Baehr declares that she has no conflict of interest. Brian J. Browne declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abir M, Choi H, Cooke CR, et al. Effect of a mass casualty incident: clinical outcomes and hospital charges for casualty patients versus concurrent inpatients. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2012;19:280–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Types of Quality Measures. July 2011. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/talkingquality/create/types.html. Accessed on 20 Nov 2018

- American College of Emergency Physicians Health care system surge capacity recognition, preparedness, and response: policy statement. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2012;59:240–241. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Hospital Association: Hospital Emergency Preparedness and Response. April 15, 2014. www.aha.org/content/14/ip-hospemerprepared.pdf. Accessed on 21 Nov 2017

- American Hospital Association: Hospital Database. https://www.ahadataviewer.com/about/hospital-database/. Accessed 8 March 2018

- Asplin BR, Flottemesch TJ, Gordon BD. Developing models for patient flow and daily surge capacity research. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1109–1113. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaujean AA. Latent variable modeling using R: a step-by-step guide. New York: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- bParati: hpp cooperative agreement. 2017. https://www.bparati.com/Hospital-Preapredness-Program-Cooperative-Agreement-Funding-Opportunity. Accessed on 8 March 2018

- Djalali A, Castren M, Khankeh H, et al. Hospital disaster preparedness as measured by functional capacity: a comparison between Iran and Sweden. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2013;28:454–461. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X13008807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djalali A, Carenzo L, Ragazzoni L, et al. Does hospital disaster preparedness predict response performance during a full-scale exercise? A pilot study. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2014;29:441–447. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X1400082X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobalian A, Stein JA, Radcliff TA, et al. Developing valid measures of emergency management capabilities within US Department of Veterans Affairs Hospitals. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2016;31:475–484. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X16000625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V. From alpha to omega: a practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br. J. Psychol. 2014;105:399–412. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation: A Study of Active Shooter Incidents in the United States Between 2000 and 2013. 2013. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-study-2000-2013-1.pdf/view. Accessed on 8 March 2018

- Hanfling D. Boston bombings and resilience-what do we mean by this? Front. Public Health. 2014;2:25. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidaranlu E, Khankeh H, Ebadi A, Ardalan A. An evaluation of non-structural vulnerabilities of hospitals involved in the 2012 east Azerbaijan earthquake. Trauma Mon. 2017;22:e28590. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Crisis standards of care: a systems framework for catastrophic disaster response. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Hospital-based emergency care: at the breaking point. Washington: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins PC, Richardson CR, Norton EC, et al. Trauma Surge Index: advancing the measurement of trauma surges and their influence on mortality. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015;221:729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji AH, Koenig KL, Lewis RJ. Current hospital disaster preparedness. JAMA. 2007;298:2188–2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji AH, Lewis RJ. Assessment of the reliability of the Johns Hopkins/Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Hospital disaster drill evaluation tool. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2008;52:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelen GD, McCarthy ML. The science of surge. Acad. Emerg Med. 2006;13:1089–1094. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M, Johnson K. Applied predictive modeling. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kelen GD, Troncoso R, Trebach J, et al. Effect of reverse triage on creation of surge capacity in a pediatric hospital. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:e164829. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcozzi, D.: During Times of Crisis Our Health-Care Delivery is Still Lagging. The Hill, 2018. https://thehill.com/opinion/healthcare/389276-during-times-of-crisis-our-health-care-delivery-is-still-lagging. Accessed on 20 Nov 2018.

- Marcozzi DE, Lurie N. Measuring healthcare preparedness: an all-hazards approach. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2012;1:42. doi: 10.1186/2045-4015-1-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mass Shootings: Washington, DC: Gun Violence Archive, 2018. https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/mass-shooting. Accessed 20 Nov 2018

- McCarthy ML, Aronsky D, Kelen GD. The measurement of daily surge and its relevance to disaster preparedness. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2006;13:1138–1141. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Forum: Healthcare System Readiness. https://www.qualityforum.org/ProjectDescription.aspx?projectID=87833. Accessed on 20 Nov 2018

- Norman ID, Aikins M, Binka FN, Nyarko KM. Hospital all-risk emergency preparedness in Ghana. Ghana Med. J. 2012;46:34–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response: 2017–2022 Health Care Preparedness and Response Capabilities. November 2016. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/reports/Documents/2017-2022-healthcare-pr-capablities.pdf. Accessed on 20 Nov 2018

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response: Hospital Surge Evaluation Tool. August 2017. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/surge/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed on 7 Oct 2019

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response: Health Care Coalition Surge Test. April 2018. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/Pages/coaltion-tool.aspx. Accessed on 7 Oct 2019

- Revelle, W.: An Overview of the Psych Package (2017). https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/surge/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed on 12 March 2018

- Rockenschaub G, Harbou KV. Disaster resilient hospitals: an essential for all-hazards emergency preparedness. World Hosp. Health Serv. 2013;49:28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinson L, Mutter R, Viboud C, et al. Impact of the fall 2009 influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic on US hospitals. Med Care. 2013;51:259–265. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827da8ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simiyu CN, Odhiambo-Otieno G, Okero D. Capacity indicators for disaster preparedness in hospitals within Nairobi County, Kenya. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014;8:349. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.349.3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton SJ, Tyler RD. Characteristics of medical surge capacity demand for sudden-impact disasters. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2006;13:1193–1197. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. What is medical surge? 2012. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/mscc/handbook/chapter1/Pages/whatismedicalsurge.aspx. Accessed on 8 March 2018

- Watson SK, Rudge JW, Coker R. Health systems’ “surge capacity”: state of the art and priorities for future research. Milbank Q. 2013;91:78–122. doi: 10.1111/milq.12003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- What Part A Covers. Medicare. Gov. www.aha.org/content/14/ip-hospemerprepared.pdf. Accessed on 20 Nov 2018