Abstract

Objectives

Previous studies on patient-centred care (PCC) and its facilitators and barriers usually considered specific patient groups, healthcare settings and aspects of PCC or focused on expert perspectives. The objective of this study was to analyse patients’ perspectives of facilitators and barriers towards implementing PCC.

Design

We conducted semistructured individual interviews with chronically ill patients. The interviewees were encouraged to share positive and negative experiences of care and the related facilitators and barriers in all settings including preventive, acute and chronic health issues. Interview data were analysed based on the concept of content analysis.

Setting

Interviews took place at the University Hospital Cologne, nursing homes, at participants’ homes or by telephone.

Participants

Any person with at least one chronic illness living in the region of Cologne was eligible for participation. 25 persons with an average age of 60 years participated in the interviews. The participants suffered from various chronic conditions including mental health problems, oncological, metabolic, neurological diseases, but also shared experiences related to acute health issues.

Results

Participants described facilitators and barriers of PCC on the microlevel (eg, patient–provider interaction), mesolevel (eg, health and social care organisation, HSCO) and macrolevel (eg, laws, financing). In addition to previous concepts, interviewees illustrated the importance of being an active patient by taking individual responsibility for health. Interviewees considered functioning teams and healthy staff members a facilitator of PCC as this can compensate stressful situations or lack of staff to some degree. A lack of transparency in financing and reimbursement was identified as barrier to PCC.

Conclusion

Individual providers and HSCOs can address many facilitators and barriers of PCC as perceived by patients. Large-scale changes such as reduction of administrative barriers, the expansion of care networks or higher mandatory nurse to patient ratios require political action and incentives.

Trial registration number

DRKS00011925

Keywords: qualitative research, care process, patient-centred care, interview, patient-provider interaction

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Interviewees had a diverse background in disease and treatment experiences, including acute and chronic illness care.

The open nature of the interviews encouraged interviewees to express various positive and negative experiences resulting in a rich collection of facilitators and barriers of patient-centred care from the patient perspective.

Due to self-selection, our sample might be biased since probably more involved and active patients participated.

Introduction

The number of studies including the term ‘patient-centred care’ (PCC) continuously increased during the last three decades.1 PCC also gained recognition and acceptance in policy and practice.1–4 Moreover, the importance of the patients’ perspective in care is reflected, for example, by introducing and implementing patients’ rights acts.5 6 Usually, themes, such as the biopsychosocial perspective, coordinated care, proactive care, integrated and continuous care, proactive and prepared care teams, shared decision making, individual needs, are associated with PCC.7–14 These themes are relevant for all patients, but received growing attention with the ageing of the population, the worldwide increase of chronic disease incidence and multimorbidity of patients.15 While acute health problems can often be treated by one professional, with one intervention in one setting, care for chronically ill patients requires integrated, coordinated, continuous care usually from various health and social care organisations (HSCOs).16 The effects of the demographic and epidemiological developments on the delivery system require change in structures, processes and goals of care (ie, cure vs effective long-term management). To addresses the shift in healthcare needs of chronically ill patients, while still meeting needs of patients with acute health problems, PCC is considered an adequate concept.17 18 Up until now, no universal definition of PCC or its facilitators and barriers exists despite extensive work on the topic. In 1969, Balint described the core aspect of PCC as considering a patient as a ‘unique human-being’ (Balint, p269)19 instead of purely looking at an illness to treat. Later, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) established the widely accepted definition of PCC as ‘care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions’ (p5).20 A similar definition is used by Reynolds who defined PCC as care which ‘focuses on the patient and the individual's particular healthcare’.21 Despite the variety of definitions of PCC, these definitions usually include the concepts of considering the patient’s individuality beyond clinical diagnoses, reacting to the individual’s needs, preferences and values. In its report ‘Crossing the Quality Chasm’ the (IOM now National Academy of Medicine) named six core principles of high quality care, with PCC being one of them.20 To implement PCC the IOM defined eight guiding principles: respect for patients’ preferences, coordination and integration of care, information and education, physical comfort, emotional support, involvement of family and friends, continuity and transition, as well as access to care.22 These guiding principles have been taken up by subsequent conceptual papers and reviews even though some principles were termed differently or two or more principles are reflected in one additional term such as ‘shared decision making’ reflecting ‘respect for patients’ preferences’ and ‘information and education’.7–14 23 24 Previous models of PCC and studies identifying barriers and facilitators for its implementation focused on expert opinions,7 17 23 25–29 conducted patient interviews with a very specific patient group,14 30–32 or addressed only specific care settings.24 29 33 34 ‘A comprehensive investigation of barriers and facilitators of the identified dimensions of patient-centredness is necessary’ (Scholl et al, p8)7 especially from the patient perspective. Additionally, previous comprehensive reviews or individual studies on barriers and facilitators of PCC lacked information on the macrolevel, that is, laws, regulation, policies, payment and reimbursement.7 Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators of PCC related to the microlevel, mesolevel and macrolevel of care, as perceived from patients’ perspectives including a broad range of disease and treatment experiences.

Methods

The study conduct and reporting is based on the ‘Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research’.35

Setting: German health and social care system

In the German healthcare system, ambulatory care, hospital care, ambulatory and stationary rehabilitation and nursing care is provided. Ambulatory healthcare is mainly provided at local physician offices, with general practitioners (GPs) usually being the first contact persons. However, patients can opt for an ambulatory specialist visit directly and without additional out-of-pocket costs. Hospital care ranges from regular basic hospitals to centres of medical excellence usually being an academic hospital, which provide care for all indications and levels of disease severity. Ambulatory care, inpatient hospital care, rehabilitation, local therapist and long-term nursing care each have their own mode of financing and reimbursement and are often separated from a delivery, but also a financial perspective.36 As an example to overcome this separation, improve chronic illness care and incentivise care integration, disease management programmes (DMPs) are implemented in Germany.37 As health and social care often provided simultaneously and some aspects of care provision are addressed in health insurance acts, and others in additional acts on social insurances (nursing insurance, accident insurance, pension insurance), the term ‘health and social care’ is used in this study. The term ‘PCC’ is associated more with functional recovery and ‘person centred care’ considers the overall well-being of a person.38 39 Based on this differentiation, ‘PCC’ will be used throughout this article since it better reflects the German statutory health insurances’ Social Health Insurance (SHI) tasks of ‘maintaining, recovering or improving an insurees health state’ (SGB V).40

Patient and public involvement

This project was conducted within the Cologne Research and Development Network (CoRe-Net), which consists of scientists, patient organisations, HSCOs, municipality representatives and other stakeholders.41 The data collection for this study took place within the research project OrgValue (Characteristics of Value-Based Health and Social Care from Organisations’ Perspectives), which is one of currently four projects affiliated with CoRe-Net.42 CoRe-Net members participated in developing ideas on the study conduct. The study results were partly presented at public CoRe-Net events and will be disseminated to all participants.

Participant recruitment and sample

To be eligible for this study, participants had to be 18 years or older and feel cognitively and emotionally able to participate in an interview. They also had to be diagnosed with at least one chronic condition to be able to share experiences from acute and chronic illness care. Participants were recruited via newspaper advertisement, flyers and posters distributed at public places, primary care physician offices, and nursing homes. The diversity of sampling strategies was used to reach maximum variation43 regarding age, gender or disease-specific characteristics (physical and mental health indications, fluctuating and stable symptoms, life-threatening diseases).

Data collection methods and setting

Data were collected through individual interviews from January to May 2018. Depending on the participants’ mobility or preference, the interviews took place at a meeting room in the University Hospital, in their long-term care institution, at home or by telephone. Prior to the interviews, each interviewee was called to provide explanations of the study. After this phone call, participants received informed consent forms describing aims and procedures of the study and a questionnaire on sociodemographic and disease specific data. These data were used to prepare the interviewer for the personal situation of the interviewee and get acquainted with disease characteristics.

The first author (VV) conducted all interviews, and the process of interviewing was regularly discussed in the interdisciplinary research team. The interviews were guided by a semistructured interview guide including open-ended questions posed in flexible order (online supplementary file 1). The interview guide was developed by extracting aspects of PCC from previously published models and reviews.7 9 17

bmjopen-2019-033449supp001.pdf (218.1KB, pdf)

Each interview started with a personal introduction of the interviewer including position and research interests. In the interview, participants were asked to describe situations, in which they experienced as optimal and suboptimal healthcare subjectively judged provision. For both situations, participants were encouraged to explain the facilitators and barriers that made them judge their experiences as optimal or suboptimal. The interviewer followed up on topics, which participants initially mentioned as minor comments. The interviews were finalised by collecting ideas and suggestions, for changes in healthcare provision, which they perceive of added value. Throughout and after the interviews participants were allowed to ask questions. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim according to scientific guidelines.44

An iterative process of data collection and analysis was applied. This included listening to audiotapes after each interview, discussing preliminary results in the research team and identifying topics needing more detailed discussions in subsequent interviews. Each participant was offered to contact the researchers after the interview by phone or email to share additional ideas or memories. Field notes were taken after the interview in case any particular observations or a specific atmosphere was noticed. Participants were allowed to access, correct or withdraw their audiotapes or transcripts.

Data analysis

Data were analysed based on concepts of qualitative content analysis based on Miles et al.43 The coding scheme was developed in a combination of an inductive and deductive approach. Themes from previous concepts of PCC were complemented by themes emerging from the data. Existing codes related to the categorisation of facilitators and barriers into the microlevel, mesolevel and macrolevel as described by Scholl et al.7 Aspects of care provision which relate to individual interactions between a patient and a care provider or other contact persons were coded under micro level. The mesolevel included aspects related to one care providing organisation (mesolevel 1) or the cooperation of several care providing organisations (mesolevel 2). Laws, regulations, policies and guidelines shaping healthcare provision were considered facilitators and barriers on the macrolevel. The subcodings were developed, revised and finalised by the team of researchers (KIH, HH and VV) alongside conducting the interviews. Using this scheme, at least two researchers (KIH, HH and VV in varying teams) coded each interview. Data coding was performed using MAXQDA V.12. Prior to data collection and analysis, all researchers received training in qualitative research methods.

Results

Participants and atmosphere

Thirty-two persons reported interest to participate in the study of which interviews took place with 25 persons. The remaining could not be followed up, were unable to read and sign informed consent materials or could not be interviewed for other reasons. Participants suffered from diseases such as breast and gastric tumours, diabetes mellitus type 2, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression and anxiety disorder, hypertension, hypercoagulability with thrombosis and embolism or multiple sclerosis. Online supplementary file 2 contains additional information on participants’ healthcare experiences. Sociodemographic characteristics of the 25 analysed participants are summarised in table 1. While one interview was terminated after 6 min due to cognitive limitations of the participant, the interviews lasted 30–80 min with an average of 44 min. The variation of interview length resulted from varying amounts of experiences with or ideas for implementing PCC. Participants were open, dared to be critical and perceived the interview as a good opportunity to share experiences. For some participants, the interview was very emotional. Participants also described situations of close relatives or friends to illustrate their understanding of PCC. One participant contacted the researchers after the interview to share additional experiences, which were considered in the analysis. After around 20 interviews no new themes emerged.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics

| Characteristic | No of participants (%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 8 (32) |

| Female | 17 (68) |

| Age | |

| 18–29 | 2 (8) |

| 30–39 | 1 (4) |

| 40–49 | 3 (12) |

| 50–59 | 5 (20) |

| 60–69 | 5 (20) |

| ≥70 | 9 (36) |

| Marital status | |

| Living with partner (married) | 8 (32) |

| Living with partner (unmarried) | 1 (4) |

| No partner, divorced or widowed | 15 (60) |

| Number of other persons within household | |

| 1 | 12 (48) |

| 2–3 | 11 (44) |

| ≥4 | 1 (4) |

| Education | |

| No degree | 0 |

| Secondary school | 5 (20) |

| High school | 6 (24) |

| College | 13 (52) |

| Other degree | 1 (4) |

| Professional qualification | |

| Vocational training | 11 (44) |

| University degree | 10 (40) |

| Retired | 15 (60) |

| Net household income | |

| €500–€999 | 3 (12) |

| €1000–€1499 | 5 (20) |

| €1500–€1999 | 1 (4) |

| €2000–€2499 | 8 (32) |

| €2500–€2999 | 2 (8) |

| ≥€3000 | 2 (8) |

| Degree of disability* | |

| 0 | 13 (52) |

| 1–19 | 0 (0) |

| 20–39 | 1 (4) |

| 40–59 | 6 (24) |

| 60–79 | 1 (4) |

| 80–100 | 3 (12) |

| Nursing scheme† | |

| None | 22 (88) |

| 1 | 1 (4) |

| 2–4 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 (4) |

If number of patients ≠ 25, data are missing.

*Higher value corresponds to greater extent of impairments.

†Higher nursing scheme represents a greater need for nursing care.

bmjopen-2019-033449supp002.pdf (30.8KB, pdf)

Facilitators and barriers of PCC

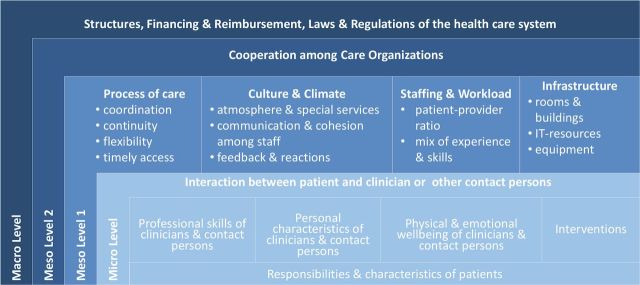

Figure 1 summarises the facilitators and barriers as identified from the patient perspective. The identified facilitators and barriers on the microlevel relate to patient and contact person characteristics (personal and professional), the physical and emotional well-being of the contact person, and the available interventions, which all together shape the interaction between patient and contact persons. On the mesolevel, facilitators and barriers related to processes of care, the culture and climate in a healthcare organisation, staffing and the healthcare organisation’s infrastructure. The structures, financing, reimbursement, laws and regulations shaping the healthcare system were identified as barriers and facilitators on the macro level. Citations for the corresponding barriers and facilitators are displayed in online supplementary file 3.

Figure 1.

Facilitators and barriers of patient-centred care. IT, information technology.

bmjopen-2019-033449supp003.pdf (288KB, pdf)

Microlevel: facilitators and barriers of the interaction between patient and clinicians or other contact persons

Responsibilities and characteristics of patients

Interviewees reported their role in establishing a good provider–patient relationship as a facilitator. It was considered especially helpful if patients share all health problems with the healthcare provider and treat the provider with respect. Moreover, communicating personal wishes or fears (eg, anxiety disorder) upfront was seen as a precondition for consideration by the provider. Interviewees acknowledged the necessity of being open to take up suggestions of the care provider, also if they require active participation in care (eg, psychotherapy, physical activity, healthy diet). Patients described the responsibility to show a high level of self-initiative and commitment within the current healthcare system to receive safe and effective care. This included medical (eg, regular administration of tablets) as well as organisational (make appointments in time), and informational (collect and organise medical and non-medical information) duties. Moreover, some patients perceived a financial responsibility to save some money for non-reimbursed therapies or copayments. Patients highlighted, however, that such a high level of self-responsibility cannot be expected from all patients in every situation (eg, in case of mental health problems, bedfastness, lower education, unemployment). Especially patients with mental illnesses felt burdened by coordinating care from different and often unknown providers, and to inform themselves adequately.

Patients differentiated their role as customers in the healthcare system in comparison to their role as customers in other situations, which implied, for example, that waiting times even for scheduled appointments sometimes just need to be accepted since healthcare cannot be timed exactly. Patients described their and other patients’ duty to request existing healthcare services in an efficient manner, for example, by contacting emergency primary care services instead of the hospital emergency departments whenever possible. Also they consider themselves and other people responsible for treating short-term minor complaints individually without seeking professional care immediately and thereby using physician time, which might be needed by more seriously ill patients. Few interviewees exclusively considered health professionals responsible for their patients’ health status.

Professional skills of clinicians and contact person

Participants expected providers to possess comprehensive medical knowledge to make a fast and accurate diagnosis based on state-of-the-art knowledge; and can offer treatments which are effective, safe, easy to administer and integrate into daily routine, while fitting the individual patient’s needs. Taking a holistic view on the patient, considering family history (eg, genetic predispositions), the current personal situation and the patient’s social environment were mentioned as prerequisites for PCC. Some patients appreciated knowledge and official qualifications on complementary medical therapies, since it broadens the therapeutic scope of a provider.

Finally, continuous trainings and specialisations were considered to improve provider skills. Especially, communication skills for interacting with, for example, demented or anxious patients were regarded as facilitators of PCC. Complementary, expertise and professionalism were considered relevant to assess own professional limits in treating specific patients and, depending on these limits, referring the patient to a specialised colleague. Next to clinicians, participants referred to other professions who facilitate PCC provision, for example, by managing transitions between HSCOs (case managers), maintaining proper hygiene (cleaning staff) or providing information and guidance (receptionists).

Personal characteristics of clinicians and contact persons

Individual participants reported a variety of care providers’ personal characteristics facilitating PCC. All were considered necessary to maintain humanity in care, but their degree of importance and expected intensity differed depending on patients and situations of seeking care. First providers must be present and pleasant, meaning that they should focus on the patient and should not be distracted or pressured (eg, by time constraints) during patient appointments. Specifically, providers ought to create a friendly and pleasant atmosphere and dedicate a sufficient amount of time to answer questions and explain treatment plans. In addition to being present, providers should also show interest and understanding for the patient’s complaints, needs and fears and take them seriously, even though they seem to be less relevant from a medical perspective. Being understanding towards the patient’s needs and use of services, conveyed towards the patient through a positive attitude (eg, reporting personal experiences, emotional involvement) without comparing one patient’s health problems to the severity of another patient were considered important facilitators. Interviewees expected providers to show commitment to the patients’ interests and responsibility for pursuing patients’ interests within the process of care, irrespective of opposing financial incentives and constraints. Moreover, providers should be flexible in making treatment plans since patients seek individualised care based on personal needs and circumstances. This includes actively considering patient preferences (eg, regarding treatment alternatives). Interviewees explained that providers should also be flexible in their behaviour and communication depending on the particular patient (eg, child vs adult, demented vs non-demented). This was also one reason why some participants considered it particularly important that providers are able to take negative feedback without feeling personally blamed or challenged by the patient. Participants stated that asking for more information or additional explanation was sometimes misconstrued as affronting professionals. They also reported feeling uncomfortable providing feedback within short consultations. Hence, taking criticism seriously was considered a valuable trait, for example, to adapt the treatment plan or developing a trustful relationship. A common reported option of expressing negative feedback was to seek health care from another provider. Finally, providers were expected to be honest and open. On the one hand, this facilitates understanding of clinicians and other person’s recommendations and instructions. On the other hand, it allows patients to critically think through recommendations and have realistic expectations about their situation. While interviewees considered all these characteristics important, none of them could compensate for low professional skills.

Physical and emotional well-being of clinicians and contact person

Participants generally acknowledged that healthcare professionals across organisations are facing a high responsibility and workload. Some participants reported situations in which work overload and exhaustion decreased the provider’s ability to provide PCC and increased the risk of errors. Patients also reported that they feel uncomfortable when requesting services from an overburdened staff member and sometimes preferred not to ask for help or information to prevent further burdening.

Interventions

Interviewees expressed several general characteristics of interventions selected during the care process. The major goal of seeking care as stated by participants was improving health or preventing deterioration of their health status by receiving interventions or recommendations, which effectively address the individual’s physical or mental health problem. Moreover, interventions facilitate PCC if they have none or individually acceptable side effects, are easily administrable and can be integrated into the individual patient’s daily living. What to consider effective, acceptable side effects or easily administrable differed between patients, for example, due to differing perceptions of sensitiveness to side effects and different individual treatment expectations.

Mesolevel (1): facilitators and barriers related to HSCOs

Process of care within an organisation

Coordination of care

Participants report various deficits, but also positive experiences of related coordination of care. Waiting times were perceived as acceptable if the provider later on also takes sufficient time for patients or if more severely ill patients were prioritised. Nevertheless, patients often assumed deficits in the coordination of care processes instead of emergencies to be the cause of waiting times.

Interviewees reported that the delivery of documents and information often happens due to the patient's initiative rather than as an institutional process. A joint coordination of the following procedures in care was requested by interviewees. This implied, for example, communicating the next diagnostic or therapeutic steps as well as discharges or referrals to another care provider. Related to inpatient hospital care interviewees reported their appointments sometimes to be cancelled at short notice or that patients have been forgotten for therapy. This seemed to be a minor problem in nursing homes, where interviewees perceived a regular and predictable schedule. Regarding structured care programmes (eg, DMP), interviewees valued the well-coordinated care process, but sometimes also felt controlled if follow-up intervals were not adapted to individual needs, but strictly followed a guideline.

Continuity of care

For participants, PCC is facilitated through continuity of the process and continuity in contact persons. Interviewees requested, for example, aligned and gapless care, meaning, that someone oversees and coordinates all steps of care and can guide the patient through the process. Especially at points of transitions or significant interventions, interviewees requested a structured check, for example, regarding the question whether the patient is able to fulfil activities of daily living or needs help. Interviewees also mentioned that sometimes a longer time frame lies in between diagnostics and start of treatment, implying a disrupted care process during which the patient is left on its own. Continuity of care was perceived as being established satisfactorily within DMPs since regular appointments are required.

Continuous contact persons were highlighted as an important facilitator of PCC, since establishing relationships of trust and in-depth knowledge of individual medical history takes time. Interviewees explained this theme in particular in relation to GPs. Especially elderly participants, participants with life-threatening disease or with mental health problems reported difficulties in getting acquainted with new people over and over again. Frequent changes in contact person were reported to occur often during hospital care.

Flexibility of care

Next to the individual care provider’s flexibility, participants appreciated flexibility of care processes in organisations in terms of individualised planning of care adapted to the needs of patients and relatives. This included, for example, consultation hours, which are feasible for fulltime employees especially those with chronic diseases, who often have medical appointments. Moreover, individually planned transitions, or a flexible change of appointments and a self-initiated appointment allocation (eg, via online systems) were requested. Positively evaluated examples were especially rehabilitation units with individualised therapies and schedules, which is adapted flexibly to the patient’s needs. In line with this, individual decisions on hospital discharge in cooperation with the patient were positively evaluated, for example, if patients need to organise home modification or nursing services.

Timeliness of access to care

Participants requested waiting times for appointments to be reasonable. This was considered an important criterion of well-organised care. Participants regarded it difficult to get specialist appointments promptly, especially when being insured with the SHI and that despite appointments they often have to wait a long time in the waiting room. Particularly waiting times for diagnostics or treatments in the course of serious diseases such as cancer was perceived as very stressful. The acceptability of waiting time length for and at appointments varied between participants, for example, in relation to disease severity or depending on whether participants were retired or working fulltime. Interviewees explained that transparency about processes and reasons for delays would contribute to higher acceptance of waiting time. Interviewees consider GPs’ support in finding specialists a facilitator for receiving care more quickly. To do so, participants considered GPs who operate in networks or medical service centres valuable.

Culture and climate

Atmosphere and special services

A welcoming atmosphere and a feeling of being respected within a HSCO or its units were perceived as facilitators of PCC. Interviewees considered an accepted leader and content staff members necessary for a good atmosphere. A ‘conveyor-belt’-like climate at HSCO was experienced to be barrier for PCC. The provision of non-medical special services such as magazines, water, coffee or tea made interviewees feel welcome at a HSCO; and depending on waiting times these were even considered necessary (eg, water).

Communication and cohesion among staff

For participants’ perspective staff members communicating harshly with each other or negatively about other patients induced daunting feelings, which was perceived as a barrier to PCC. Communicating calm and friendly despite stressful situations was reported to calm down patients and facilitates the feeling of being cared for by a competent and functioning team. The style of communication was also perceived to be linked to the level of cohesion among staff members. Interviewees explained that even the most experienced and skilled care providers can only provide PCC if they work closely together, support each other and apply the variety of staff skills as needed disregarding hierarchies. Sometimes interviewees even had the feeling that a well-functioning team can compensate a lack of staff members. Participants perceived a higher level of task separation being a barrier to PCC, since care providers would feel responsible for only a minor part in the process of healthcare provision.

Feedback and reactions

Interviewees would value structured feedback options such as patient surveys on the level of HSCOs, first to improve their own care, but also to improve care for future patients in a particular HSCO. Since structured feedback methods are not common -especially in the ambulatory care sector—the only way to express negative feedback is seeking care from another HSCO. This was often considered necessary since other options were unavailable. Participants who expressed feedback (verbally or in writing) felt disregarded and very disappointed if such feedback was not replied to either through a dialogue or by implementing suggested improvements in the HSCO.

Staffing and workload

Patient–provider ratio

Interview participants described that teams of care providers can only provide good care if the number of staff is sufficient in relation to the number of patients. An adequate staff to patient or staff to task ratio, respectively, was regarded important to maintain safety, hygiene and effectiveness in care.

Mix of experience and skills

Next to a sufficient number of staff, interviewees considered the mix of experience and skills within the team as facilitating or impeding PCC. This mix facilitates, for example, inexperienced staff members being supported by experienced colleagues in practical and communicative skills. Interviewees considered different professions within a HSCO as a facilitating factor since for example, various examinations and treatments could be performed at one place.

Infrastructure

Rooms and buildings

Interviewees described the relevance of the built environment on their care. First, HSCO needs to be accessible for all patients, which includes being geographically close to patients’ homes, having wheel-chair ramps and informative signs. Interviewees expectations related to inpatient care included clean and modern facilities with small units. Patient rooms, which allow for privacy and recovery, were considered valuable. Shared rooms with only two to three patients or separate rooms for examinations and consultations with care providers facilitate PCC. Also sharing bathrooms with less people was considered more comfortable and hygienic. Interviewees perceived private conversations with relatives and friends to be facilitated by safe havens such as seating areas away from hallways or waiting areas While interviewees appreciated that hospitals are not hotels, negative experiences such as dirty facilities or confined spaces considerably influenced participants overall perception of patient-centredness in a HSCO.

Information technology

Interviewees explained that the availability and use of information technology was important to reduce loss of information between different departments especially in the case of large

Mesolevel 2: facilitators and barriers related to the cooperation among HSCOs

At this mesolevel 2, patients considered all factors summarised under processes of care described on the level of one organisation relevant for the collaboration between organisations as well. Barriers experienced by participants mostly related to coordination and continuity of care, for example, when information was not provided to subsequent care providers. Moreover, coordination barriers were experiences when transitions between HSCOs were not planned well or none of the involved HSCO felt responsible, but always another provider is assumed to take responsibility. Hence, a specific person who is responsible for the overall care process was suggested as a facilitator for PCC. Participants reported experiencing repetitive diagnostics, as a barrier for PCC, since all care providers should perform diagnostics at the same level of quality and share their results. Moreover, interviewees considered such diagnostics inappropriate cost drivers and felt that time consumed for repetitive diagnostics could be used more effectively (eg, explaining procedures). Interviewees reported a lack of information when being referred to other providers, and receiving specific recommendations for a provider was considered helpful in finding qualified providers, but also providers who smoothly cooperate with the patient’s GP.

Macrolevel: facilitators and barriers related to structural, financial and legal conditions of care provision

Structures of the health care system

Participants described the structures of the German healthcare as very complex and sometimes confusing with its high degree of separation. Interviewees often mentioned that they were sent to other providers since the provider they contacted was not the primarily responsible provider for the particular health problem at stake. This was especially the case for ambulatory out-of-office hour GP practices, which were meant to be visited instead of hospital emergency departments in case of non-life-threatening conditions. In line with this, interviewees described examples of the fragmentation of care provision for example, by having to contact different providers at different locations of whom none feels responsible for the overall care process. Interviewees felt not educated well about the structures of the healthcare system to prevent unnecessary or wrong utilisation of healthcare services.

Financing and reimbursement

Interviewees considered fairness elements in modes of insurance payment and service provision a facilitator of PCC. This includes, for example, that contributions to the SHI are levied as percentage of actual income or receiving care based exclusively on medical need. Sometimes patients perceive the insurance status (statutory or private) leads to differences in treatment not justified based on medical need. This was illustrated, for example, by being asked first about the health insurance when requesting an appointment rather than being asked about the medical condition.

Regarding reimbursement, interviewees often expressed that they do not understand why particular therapies are reimbursed and others are not. Ambulatory physicians in Germany have a so-called care budget, which they have available for distribution among patients and interventions. Participants often did not know whether physicians do not prescribe, for example, medication or therapy because the physician considers it too expensive to prescribe this from the care budget, whether it is not covered by the insurance in general or whether care providers actually base their recommendation on the effectiveness, given the clinical situation. The same doubts were reported for recommendations regarding out-of-pocket paid interventions. Only few participants were aware of specific reimbursement processes and most perceived reimbursement decisions to be intransparent. Such complexity of payment schemes and non-transparency was reported to induce distrust towards providers and insurances, and a feeling of insecurity regarding trustworthiness of recommendations. Several interviewees also called for the extension of the SHI’s benefits catalogue particularly for naturopathy, homeopathy, eurhythmics or other alternative forms of therapies, since they experienced them as helpful in their personal care process and facilitating PCC.

Laws and regulations

Interviewees described that they perceive supervising mechanisms of clinical care practice such as regular audits of physicians to be unavailable or implemented insufficiently. These were considered necessary since interviewees themselves felt insecure about judging the quality of medical care by themselves. In the case of perceived medical errors, overtreatment and undertreatment interviewees were unsure how to react. Regular checks of local physician offices by an independent institution were considered to facilitate PCC.

Interviewees also perceived the integration of healthcare with other social services related to healthcare as suboptimal. The health insurance is responsible for covering the treatment of patients, while the pension insurance is responsible for the payment of rehabilitation of working patients. Interviewees perceived that the boundaries between treating patients and reintegrating them into the labour market are not that clear cut in practice, which sometimes lead to health insurance and pension insurance discussing about the financial responsibilities and thereby delaying care initiation. Also, rehabilitation was sometimes perceived to be approved by insurances primarily to evaluate whether patients are able to return to work fulltime instead of focussing on recovery, which patients sometimes experienced as degrading. Interviewees urged for a more timely reaction to challenges requiring political action. Since challenges such as lack of professional staff or financing and reimbursement mechanisms require political action, challenges often cannot be addressed flexible, but require long periods. During these periods, the level of PCC was perceived to decrease. Interviewees perceived the political initiatives to address problems in healthcare supply as insufficient.

Discussion

This study identified facilitators and barriers of PCC from the perspective of patients. They described facilitators and on the microlevel, mesolevel and macrolevel of health and social care.

The two facilitators of PCC on the mircolevel expressed by all participants and also observed in previous studies were receiving effective interventions7 11 and the successful interaction with contact persons.8 9 17 24 The variety of personal and professional skills facilitating PCC and their different importance in different situations illustrate that behaviours of professionals constantly need to be adapted for the particular situation and patient. Participants also perceived physically and mentally healthy staff members as being better able to provide PCC- an impression supported by other studies.26 27 45 46

In addition to previous studies, our interviews revealed that interviewees considered their personal behaviour as facilitating or impeding PCC. This included, for example, active participation in healthcare. In addition to the patient being ‘activated’ by healthcare providers as described in models of PCC7 8 11 17 an intrinsically ‘active patient’ was perceived as a facilitator for PCC. This implies that patients themselves need to be active, interested and willing to facilitate PCC. Nevertheless, to fulfil this role, patients need guidance and access to easily understandable information and therapies, which match their health and personal needs. Another finding was the importance of contact persons in health and social care beyond the usually mentioned ‘clinicians’ or ‘physicians’ in previous studies.7–9 Sometimes non-clinical staff members facilitate or impede PCC provision as much as healthcare providers. Therefore, trainings in, for example, patient communication should address all staff members who get into contact with patients.

On the mesolevel, participants described a smooth flow of information within and between organisations as well as functioning care teams with clear responsibilities as important facilitators PCC. As observed in previous studies, interviewees preferred to have continuous contact persons, which enables building trustful relationships, having a complete overview of the medical history and feeling responsible for the whole care process.7 8 11 14 Therefore, supporting teamwork and cohesion among staff members facilitate PCC in any setting.

In addition to previous studies, participants expressed the importance of a person, who is responsible for the overall care process within, but especially across HSCOs. Such care models could be encouraged and supported by further incentivising for example, integrated care contracts. Approaches such as the Guided Care Model, where a trained guided care nurse facilitates guidance through the health care system, developing a long-term treatment plan and managing patients’ transitions between HSCOs, might increase the patient perception of patient-centredness.47 48

Facilitators and barriers of PCC on the macrolevel received little attention in previous studies including patients.7 Participants considered the structure of the healthcare system, financing and reimbursement mechanisms, and laws and regulations facilitating and impeding PCC. Due to the complexity of the German health and social care systems, interviewees described that a lack of transparency and comprehensibility of regulations were perceived as barriers to PCC. This complexity can induce distrust of the patient towards the healthcare system and care providers, including non-acceptance about choices made healthcare.

Legally established structured care models, such as DMPs, were considered a facilitator for PCC, but some patients reported pressure to subscribe or felt being controlled by physicians and the SHI. Interventions intended to improve PCC need to be voluntary and despite being structured leave room for individual adaptations such as extending monitoring intervals in case of stable conditions or high adherence to care plans.49

Next to medical patient information, PCC could be strengthened by structured support in navigating through the care system.50 This navigation can be implemented for example, by GPs providing recommendations for specific specialist. However, to maintain neutrality, rules of professional conduct of physicians, referrals to specific colleagues are only allowed in case of sufficient reasoning.51

A theme regardless of the microlevel, mesolevel and macrolevel and not previously discussed in relation to PCC is the participants’ ambivalence regarding several facilitators and barriers. While participants consider the exchange of information between care providers a facilitator of PCC, they also prefer to share only specific information with specific providers, which impedes communication and interdisciplinary care. Reasons for this behaviour are diverse, (eg, embarrassment, lack of trust in provider).52 Additionally, GPs as first contact persons in healthcare were considered as facilitating PCC with regard to preventing unnecessary resource use and coordinating care. Nevertheless, interviewees perceived a formal gatekeeper system as a potential barrier to PCC, since they value the free choice of providers. Another ambivalence relates to study participants’ and German patients’ request for the most effective care, but at the same time demanding the reimbursement and more frequent use of, for example, homeopathy and other therapies, which still lack high quality evidence for its effectiveness.53 54

Strength and limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the experiences, facilitators an barriers expressed by the interviewees are subjective and might be influenced by recall bias. However, looking back for a longer period also allowed the patients to reflect on their experiences. Moreover, all patients had at least one recent care experience. Second, we only interviewed patients living in Cologne or surrounding communities. This implies an overrepresentation of the urban population. However, interviewees also reported experiences from former places of living including rural areas. As a strength, we consider the results generalisable to other regions, since none of them particularly relates to urban care provision. Moreover, the diversity of our sample regarding sociodemographic and disease-related characteristics also supports generalisability of results to other patients.

Conclusion

Many facilitators and barriers of PCC addressed by patients can be supported by changes in individual behaviours, restructuring of care processes within organisations and supporting team-based care provision. Future research should investigate the importance of individual facilitators and barriers in more detail and elicit patients’ suggestions on interventions to improve PCC in various settings and on various decision levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants of this study for sharing their experiences. We also thank our practice partners who supported recruitment of participants. Finally, we thank Deniz Senyel for her support in facilitating data analysis and preparation of supplementary materials.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Cologne Research and Development Network (CoRe-Net): Christian Albus, Lena Ansmann, Frank Jessen, Ute Karbach, Ludwig Kuntz, Holger Pfaff, Christian Rietz, Ingrid Schubert, Frank Schulz-Nieswandt, Nadine Scholten, Stephanie Stock, Julia Strupp, and Raymond Voltz.

Contributors: SS, LK and LA conceived the study. VV, KIH, HH and SS specified the methods. VV conducted the interviews. VV, KIH and HH analysed the interviews. VV drafted and revised the manuscript in cooperation with KIH and HH. All authors critically read, revised and approved the final manuscript. VV is guarantor. KIH, HH and VV were PhD candidates at the time of conducting the study. SS is professor for patient-centred care and Applied Health Economics, LA is professor for Organisation-related Health Services Research, and LK is professor of Business Administration and Health Care Management.

Funding: This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant no.01GY1606).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Cologne approved the study (Nr: 17–210).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information. Since complete transcripts of interviews potentially allow for identification of individuals, complete transcripts cannot be provided.

Contributor Information

on behalf of the Cologne Research and Development Network (CoRe-Net):

Christian Albus, Lena Ansmann, Frank Jessen, Ute Karbach, Ludwig Kuntz, Holger Pfaff, Christian Rietz, Ingrid Schubert, Frank Schulz-Nieswandt, Nadine Scholten, Stephanie Stock, Julia Strupp, and Raymond Voltz

References

- 1. World Health Organization Framework on integrated, people-centred health services. Available: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_39-en.pdf?ua=1&ua=1

- 2. Paparella G. Person-centred care in Europe: a cross-country comparison of health sytem performance, strategies and structures. Oxford, England: Picker Institute Europe, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moody L, Nicholls B, Shamji H, et al. The person-centred care guideline: from principle to practice. J Patient Exp 2018;5:282–8. 10.1177/2374373518765792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hearn J, Dewji M, Stocker C, et al. Patient-centered medical education: a proposed definition. Med Teach 2019;41:934–8. 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1597258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. PRE-MAX Consortium Patients' rights in the European Union: European Commission, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peled-Raz M. Human rights in patient care and public health-a common ground. Public Health Rev 2017;38:29. 10.1186/s40985-017-0075-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. An integrative model of patient-centeredness - a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e107828. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Langberg EM, Dyhr L, Davidsen AS. Development of the concept of patient-centredness - a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1228–36. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, et al. Measuring patients' perceptions of patient-centered care: a systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:155–64. 10.1370/afm.1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:1087–110. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00098-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brickley B, Sladdin I, Williams LT, et al. A new model of patient-centred care for general practitioners: results of an integrative review. Fam Pract 2019;16 10.1093/fampra/cmz063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, et al. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:4–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stewart M. Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ 2001;322:444–5. 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raja S, Hasnain M, Vadakumchery T, et al. Identifying elements of patient-centered care in underserved populations: a qualitative study of patient perspectives. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126708. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-GSAP-2017.pdf?ua=1

- 16. Lehnert T, Heider D, Leicht H, et al. Review: health care utilization and costs of elderly persons with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care Res Rev 2011;68:387–420. 10.1177/1077558711399580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff 2001;20:64–78. 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, et al. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff 2009;28:75–85. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Balint E. The possibilities of patient-centered medicine. J R Coll Gen Pract 1969;17:269–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Institute of Medicine (US) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reynolds A. Patient-Centered care. Radiol Technol 2009;81:133–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Picker Institute The eight principles of patient-centred care, 2019. Available: https://www.oneviewhealthcare.com/the-eight-principles-of-patient-centered-care/

- 23. Epstein RM, Street RL. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:100–3. 10.1370/afm.1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sladdin I, Chaboyer W, Ball L. Patients' perceptions and experiences of patient-centred care in dietetic consultations. J Hum Nutr Diet 2018;31:188–96. 10.1111/jhn.12507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barr VJ, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, et al. The expanded chronic care model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the chronic care model. Hosp Q 2003;7:73–82. 10.12927/hcq.2003.16763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hower KI, Vennedey V, Hillen HA, et al. Implementation of patient-centred care: which organisational determinants matter from decision maker's perspective? Results from a qualitative interview study across various health and social care organisations. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027591. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fix GM, VanDeusen Lukas C, Bolton RE, et al. Patient-centred care is a way of doing things: how healthcare employees conceptualize patient-centred care. Health Expect 2018;21:300–7. 10.1111/hex.12615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berghout M, van Exel J, Leensvaart L, et al. Healthcare professionals' views on patient-centered care in hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:385. 10.1186/s12913-015-1049-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Slatore CG, Hansen L, Ganzini L, et al. Communication by nurses in the intensive care unit: qualitative analysis of domains of patient-centered care. Am J Crit Care 2012;21:410–8. 10.4037/ajcc2012124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mead H, Andres E, Regenstein M. Underserved patients' perspectives on patient-centered primary care: does the patient-centered medical home model meet their needs? Med Care Res Rev 2014;71:61–84. 10.1177/1077558713509890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Balbale SN, Morris MA, LaVela SL. Using photovoice to explore patient perceptions of patient-centered care in the Veterans Affairs health care system. Patient 2014;7:187–95. 10.1007/s40271-014-0044-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kvåle K, Bondevik M. What is important for patient centred care? A qualitative study about the perceptions of patients with cancer. Scand J Caring Sci 2008;22:582–9. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, et al. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1923–39. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Helfrich CD, Dolan ED, Fihn SD, et al. Association of medical home team-based care functions and perceived improvements in patient-centered care at VHA primary care clinics. Healthc 2014;2:238–44. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stock S. Integrated ambulatory specialist care--Germany's new health care sector. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1781–5. 10.1056/NEJMp1413625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care What are disease management programs (DMPs)? 2019. Available: https://www.informedhealth.org/what-are-disease-management-programs-dmps.2265.en.html

- 38. Håkansson Eklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, et al. "Same same or different?" A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:3–11. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kumar R, Chattu VK. What is in the name? Understanding terminologies of patient-centered, person-centered, and patient-directed care! J Family Med Prim Care 2018;7:487–8. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_61_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB V) Fünftes Buch Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Karbach U, Ansmann L, Scholten N, et al. [Report from an ongoing research project: The Cologne Research and Development Network (CoRe-Net) and the value-based approach to healthcare]. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2018;130:21–6. 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ansmann L, Hillen HA, Kuntz L, et al. Characteristics of value-based health and social care from organisations' perspectives (OrgValue): a mixed-methods study protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022635. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fuß S, Karbach U. Grundlagen der Transkription: Eine praktische Einführung, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45. McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, et al. Nurses' widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff 2011;30:202–10. 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ansmann L, Kowalski C, Ernstmann N, et al. Do breast cancer patients receive less support from physicians in German hospitals with high physician workload? A multilevel analysis. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93:327–34. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Boult C, Karm L, Groves C. Improving chronic care: the "guided care" model. Perm J 2008;12:50–4. 10.7812/TPP/07-014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boyd CM, Reider L, Frey K, et al. The effects of guided care on the perceived quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: 18-month outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:235–42. 10.1007/s11606-009-1192-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ansmann L, Pfaff H. Providers and Patients Caught Between Standardization and Individualization: Individualized Standardization as a Solution Comment on "(Re) Making the Procrustean Bed? Standardization and Customization as Competing Logics in Healthcare". Int J Health Policy Manag 2018;7:349–52. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Peart A, Lewis V, Brown T, et al. Patient navigators facilitating access to primary care: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019252. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bundesärztekammer (Muster-)Berufsordnung für die in Deutschland tätigen Ärztinnen und Ärzte, 2019. Available: https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/pdf-Ordner/MBO/MBO-AE.pdf

- 52. Levy AG, Scherer AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information to clinicians. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e185293. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wallenfels M. Patienten wollen bei Homöopathie-Verordnungen mitreden (patients want to be involved in the prescription of Homeopathy), 2019. Available: https://www.aerztezeitung.de/praxis_wirtschaft/rezepte/article/970757/umfrage-daten-patienten-wollen-homoeopathie-verordnung-mitreden.html

- 54. Ernst E. Homeopathy: what does the "best" evidence tell us? Med J Aust 2010;192:458–60. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03585.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033449supp001.pdf (218.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033449supp002.pdf (30.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033449supp003.pdf (288KB, pdf)