Abstract

Purpose of Review:

The purpose of this review is to provide a brief summary about the current state of knowledge regarding the circadian rhythm in the regulation of normal renal function.

Recent findings:

There is a lack of information regarding how the circadian clock mechanisms may contribute to the development of diabetic kidney disease. We discuss recent findings regarding mechanisms that are established in diabetic kidney disease and are known to be linked to the circadian clock as possible connections between these two areas

Summary:

Here we hypothesize various mechanisms that may provide a link between the clock mechanism and kidney disease in diabetes based on available data from humans and rodent models.

Keywords: circadian rhythm, renal function, HIF, shift work, BMAL1

Introduction

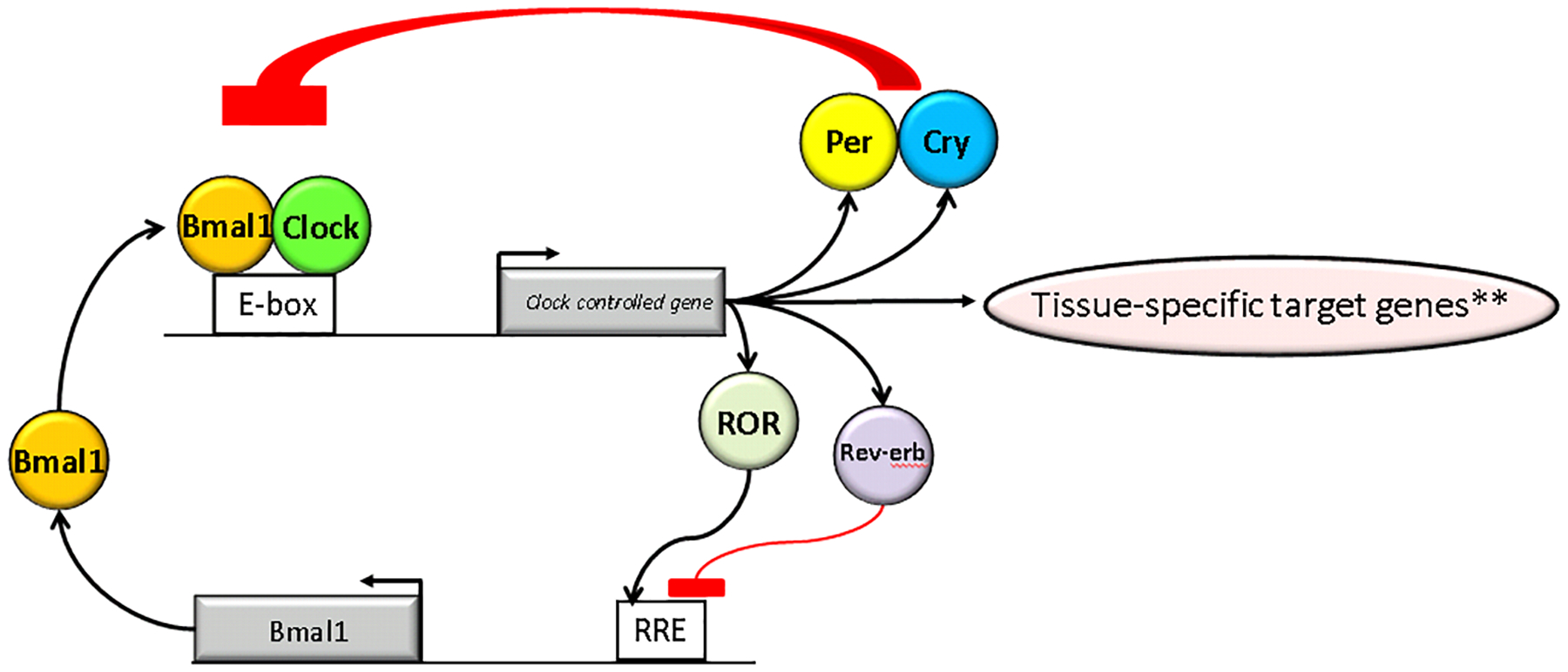

The circadian clock is a network of interconnected transcription- translation feedback loops, in which translated circadian proteins inhibit their own mRNA transcription to generate cell autonomous and self-sustaining transcriptional circadian oscillations that contribute to the regulation of most physiologic functions[1, 2]. The core mechanism is comprised of several transcription factors that participate in a transcription-translation feedback loop (Figure 1). In mammals the main feedback loop is activated by a heterodimeric transcription activator Brain and muscle ARNT-like 1 (BMAL1 or ARNTL) and the Circadian Locomotor Output Cycles protein Kaput (CLOCK). BMAL1-CLOCK heterodimers trigger the transcription of a wide range of circadian clock-controlled genes (CCGs), identified as the ‘Period’ and ‘Cryptochrome’ families of genes (PER1/PER2/PER3 and CRY1/CRY2 respectively). PER/CRY heterodimers contribute to the inhibitory feedback loop to decrease the activity of BMAL1-CLOCK. An ancillary loop involving nuclear receptors acts as an additional important feedback mechanism controlling BMAL1 transcription. This complex network is ubiquitously expressed within central nervous system and peripheral tissues including the kidneys[3–5]. An analytical study of transcriptomes of 12 adult mouse organs showed approximately 43% of all protein coding genes in the genome demonstrated circadian oscillations in at least one of the organs tested[6]. Notably, kidney was second only to the liver in terms of total number of circadian transcripts (approximately 13% compared to 16%) supporting significant presence of circadian lock activity in renal cells. Other studies also show that many circadian target genes are organ-specific and are related to tissue-specific functions[7, 8].

Figure 1.

Simplified Transcription Translation Feedback Loop Mechanism of the Circadian Clock.

**Example, HIF1a in the kidney, see Figure 2. Examples also include many genes related to renal sodium handling (see text for discussion).

Part I. Circadian rhythms in kidney function

Circadian Rhythm and the Kidney Glomerulus

The primary functions of the glomerulus include the selective ultrafiltration of plasma and clearance of small solutes, which is measured by the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Early studies in human subjects maintained on bed rest, normal sleep/wake as well as light/dark cycles, and identical standardized meals every 3 hours showed that there was a clear circadian pattern to GFR[9]٫. The GFR measured using inulin clearances was highest during the day (122 ml/min) and lowest at night (86 ml/min). The variations in GFR likely reflect changes in renal plasma flow since the clearance of p-amino-hippurate showed a similar pattern and amplitude. Urinary albumin and β2-microglobulin excretion were also noted to have a circadian rhythm in-phase with the GFR rhythm. Although very little is known about circadian dysrhythmia leading to glomerular dysfunction, proteinuria in patients with nephrotic syndrome has been observed to follow a circadian rhythm[9, 10]. However, protein excretion is independent of GFR rhythm with peak excretion around 4 pm and almost no protein excretion around 3 am [11].

Circadian Rhythm and Renal Tubules

Following selective ultrafiltration through the glomerulus, renal tubules have the important job of reabsorbing the essential components of the filtrate, while augmenting elimination of non-essential toxic and non-toxic waste products by actively secreting these into the final urinary excreta. The proximal tubule, the kidney power house in this regard, performs the bulk of reabsorption, whereas the distal tubule, along with the collecting tubule, does the fine tuning and finalizes the urine composition. Most renal functional rhythms have similar kinetics with peaks and troughs corresponding to periods of maximal and minimal behavioral activity, referred to as active and inactive phases, respectively[12]. For humans, active phase is generally during the daytime and the inactive phase during nighttime, whereas the reverse is the case in the rodent models used for biomedical research.

Urine volume, electrolyte excretion, and blood pressure all exhibit circadian variation. A normal circadian blood pressure pattern is associated with a 10–15% decrease in blood pressures at night called a ‘dipping” pattern. We have shown that the α subunit of the epithelial sodium channel (αENaC) exhibits a circadian pattern of expression and Period 1-deficient mice have altered expression of αENaC and develop salt-sensitive, non-dipping hypertension[13, 14]. We have also shown that Period 1 regulates the expression of other sodium handling genes in the kidney[15–17]. Transcriptome-wide studies and targeted gene-specific analyses have revealed rhythmic expression of other genes important in salt and water balance including aquaporins, urea transporters and potassium channels[18–21]. Consistent with a critical role for the circadian clock in the regulation of renal gene expression, genetic inactivation of the Clock gene leads to notable changes in the kidney transcriptome [22, 23].

The most abundant protein in human urine is uromodulin (also known as Tamm-Horsfall protein). Uromodulin has been identified as a susceptibility gene for a number of kidney diseases and it has been specifically linked to diabetic kidney disease [24],[25]. Uromodulin is produced in the thick ascending limb and appears to play a role in regulating renal sodium handling, sodium-sensitivity, and forming a protective coating in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle [26]. It is not clear if uromodulin excretion displays a circadian rhythm, but its urinary levels are observed to correlate with urine volume[27] which exhibits a clear circadian rhythm. Uromodulin was recently identified as a BMAL1-target gene exhibiting differences in expression between 10 am and 10 pm in male mice[28] (see Supplemental Table 4)).

Circadian Rhythm and Renal Interstitium

Advanced DKD is characterized by interstitial inflammation and fibrosis. CLOCK may play a role in prevention of renal fibrosis and parenchymal damage. Following unilateral ureteral obstruction in a CLOCK-null mice, increased renal parenchymal damage and fibrosis were observed, suggesting that the circadian clock plays a role in regulating renal fibrosis[29] possibly by inhibiting transforming growth factor-β-cyclooxygenase 2 (TGF-β-COX2) pro-fibrotic axis in the kidney.

Circadian Rhythm and Renal Neuro-Hormonal System

External cues, including light, food intake, and circulating hormones, determine the periodicity of [(i.e. ‘entrain’)] the circadian oscillations in the kidney. Aldosterone, a mineralocorticoid hormone secreted by the adrenal glands, plays a significant role in the maintenance of extracellular sodium homeostasis and control of blood pressure in part by regulating the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), the principal sodium channel present on the apical side of the principal cells of the renal collecting duct[30]. Plasma aldosterone levels peak in the first half of the active phase, in parallel with GFR rhythms and filtered sodium load[31]. Plasma aldosterone is significantly increased, and circadian aldosterone oscillations significantly reduced, in mice deficient in CRY1 and CRY2. Analysis of the circadian transcriptome in the adrenal glands of these mice detected an increase in expression of the aldosterone biosynthetic enzyme 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/delta 5-to-4 isomerase type 6 (HSD3B6). Functional defects in CRY1/2 knockout mice included significantly elevated plasma aldosterone levels coupled with salt-sensitive hypertension and non-dipping pattern of arterial blood pressure[32].

PER1, one of the core clock components, has been demonstrated to positively regulate aldosterone synthesis in an adrenal cell line and plasma aldosterone levels in-vivo in the 129/sv strain of mice[33]. PER1-null mice on a C57Bl/6 background, under high salt and mineralocorticoid treatment conditions, develop a non-dipping form of hypertension[13, 14]. PER1 has also been shown to control the transcription of the genes encoding several key proteins involved in sodium reabsorption along the nephron (including α-ENaC, NCC, kinases WNK1 & WNK4, NHE3, SGLT1) as well as several components of the endothelin axis[34–36, 17, 37].

Emerging Concepts in Circadian Renal Function

In addition to the classic transcriptional mechanism of the circadian clock, translation occurs in a rhythmic fashion as has recently been described [38]. In the mouse liver, peak ribosome biogenesis and polysome formation occurred in the middle of the active phase, presumably because the circadian clock coordinates the energy consuming process of protein synthesis with energy production in these cells[39, 40]. Ribosomes from murine kidneys have been profiled to identify rhythmically translated mRNAs in the kidney. This compelling study demonstrated that nearly 10% of all detected transcripts were translated in a circadian pattern. [38]. These findings demonstrate that circadian rhythms in function likely relate to rhythmic changes in mRNA levels, translation, and protein expression.

When correlating circadian translation with functional circadian oscillations in renal function, another level of complexity to consider is the effect of post-translational modifications. Such modifications can affect protein stability, subcellular localization, protein-protein interactions and protein function. The total levels of Na-Cl cotransporter (NCC, encoded by the SLC12A3 gene), which controls sodium reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT), do not appear to exhibit circadian oscillations but the active phosphorylated form does[41, 42]. Recent global analysis of the circadian phosphorylome and acetylome in the mouse liver revealed approximately 20,000 phosphorylation sites within 4,400 liver proteins, with approximately 25% being regulated in a circadian manner. Of the 1,000 acetylation sites found in the liver proteome, approximately 13% demonstrate circadian oscillations, particularly those involved in the urea and the tricarboxylic acid cycles in the metabolism of amino acids and lipids[43]. It remains to be seen whether post-translational modification of proteins plays a similar role in circadian oscillations of renal function.

Another emerging area concerns the role of circadian rhythms in systemic and renal oxygen levels. In mice, renal oxygen levels can affect the intrinsic renal circadian clock by inducing circadian oscillations in the levels of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α)[44]. The nuclear levels of HIF1α in the kidney oscillated, with a peak in the first half of the active phase. The mechanism appears to be suppression of mTORC1 signaling by the acid load (e.g. lactate) generated during hypoxia [45].

Part II. Potential Role for Circadian Rhythm Dysregulation in DKD

Evidence from Rodent Models and Humans

Accumulating evidence from rodent and human studies indicates that circadian disruption is prevalent in diabetes[46]. This topic has been reviewed in depth recently[47]. One example is that altered circadian expression of clock genes in the kidney has been shown in a rat model of diabetes induced by streptozotocin[48]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in BMAL1 and CLOCK have been linked to type 2 diabetes in humans[49, 50]. Shift work and chronic circadian disruption appears to cause increased risk for diabetes and other cardiometabolic disorders[51]. Consistent with these genome wide association and epidemiological studies, mechanistic evidence from circadian mutant mouse models supports a connection between the molecular circadian clock and diabetic disorders. Bass and colleagues demonstrated that BMAL1 and Clock mutant mice both develop a diabetic phenotype and that specific disruption of the pancreatic β-cell circadian clock leads to diabetes[52]. The connection between the clock and diabetes is bidirectional, as has been demonstrated by the work of Gong and colleagues using the db/db mouse model[53–55]. The db/db mice exhibit circadian dysfunction in the form of non-dipping hypertension as well as dysregulated rhythms at the level of individual peripheral clocks.

Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD)

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), a major microvascular complication of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, continues to be a leading cause of end-stage renal disease in Western nations. Classic diabetic nephropathy is characterized by nodular glomerulosclerosis on histopathology and clinically by progressive decline in renal function often preceded by albuminuria. DKD is associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality, in large part due to an increase in cardiovascular disease. Traditionally, DKD was thought to result from interactions between hemodynamic and metabolic factors resulting in increased intra-glomerular pressures and modification of molecules under hyperglycemic conditions[56]. However, growing evidence indicates that the extent of renal damage in patients with DKD is not completely explained by these factors and the pathogenesis is likely multifactorial, with genetic and environmental factors triggering a complex series of pathophysiological events[57, 58]. Inflammation is thought to be one of the key pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for DKD. The components of the diabetic milieu act on the kidneys to activate diverse intracellular downstream signaling cascades, leading to activation of several inflammatory pathways to drive mesangial hypertrophy and deposition of collagen IV & fibronectin. Activation of these signaling pathways results in infiltration by circulating inflammatory cells, thus amplifying and perpetuating the inflammatory process in the kidney. Hypertension, present in almost 65% of the diabetic population,[59] provokes additional injury resulting in the perfect storm of accelerated progressive kidney disease[60, 61].

Potential Effect of Circadian Dysrhythmia on Diabetic Kidney Disease

A non-dipping blood pressure pattern is prevalent in both type 1[62] and type 2[63] diabetics and corresponds to increased albuminuria[64]. Administration of at least one antihypertensive medication at night restores dipping status and improves clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes[65]. While these observations provide some support for dysfunction of the circadian rhythm in DKD, the molecular mechanisms underlying these defects remains to be elucidated. Below, we speculate as to possible mechanisms involving BMAL1/CLOCK, select clock target genes, and hypoxia signaling that may contribute to the clock dysfunction in DKD.

BMAL1 has been described as the main indispensable component of the core clock machinery[66]. BMAL1-null mice have a multitude of mild-to-severe metabolic alterations including impaired metabolism of glucose[67] and fatty acids[68]. Potential effect of circadian dysfunction from BMAL1 deficiency or malfunction might pave the way for impairment of glucose metabolism, a significant substrate contributor to the complex processes leading to DKD development. As discussed earlier, an optimally functioning CLOCK-driven circadian rhythm prevents renal parenchymal damage and fibrosis[29]. Thus, CLOCK deficiency or dysfunction may lower the threshold for development of microvascular disease and fibrosis or accelerate the progression of DKD.

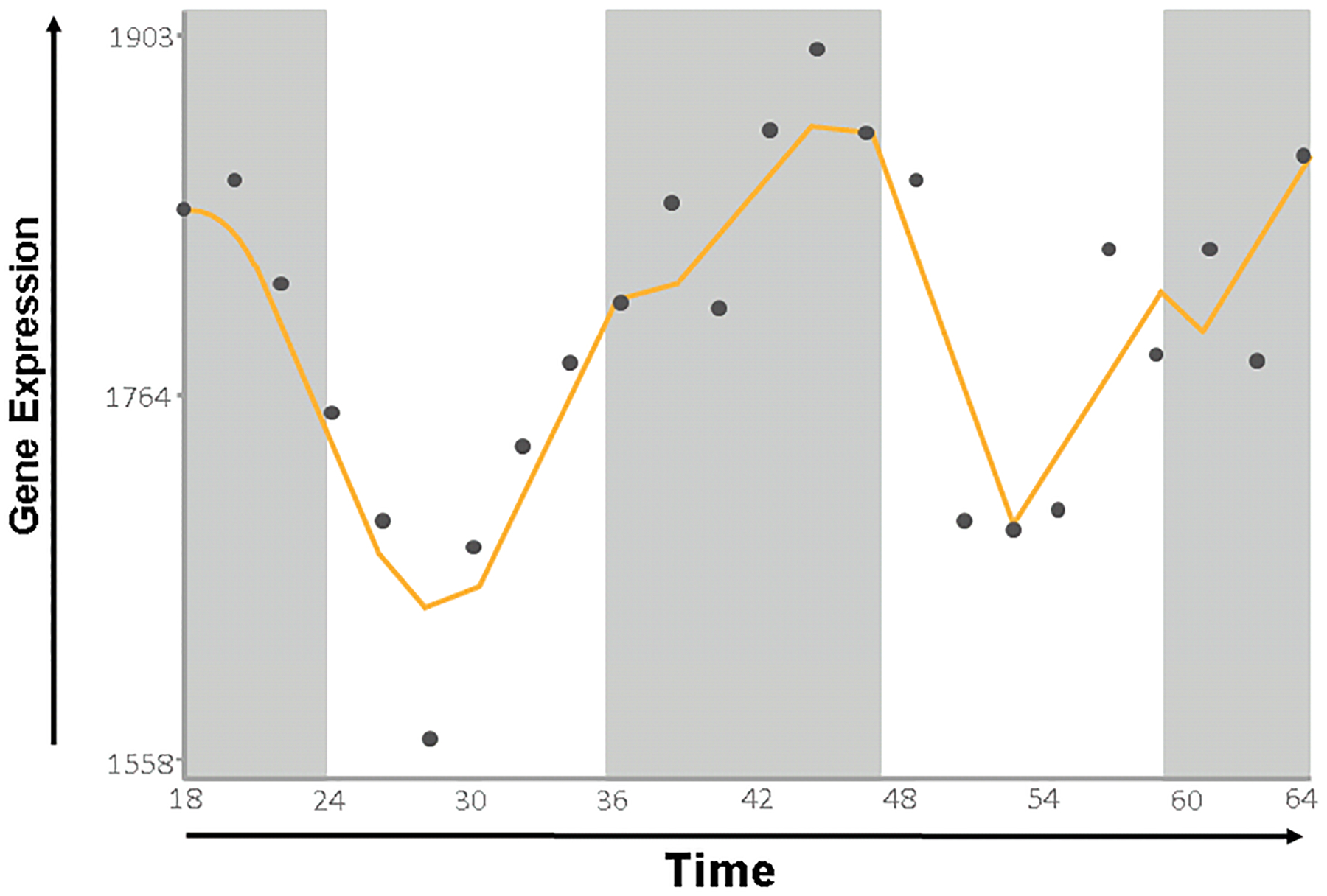

There are potential effects of circadian dysrhythmia in DKD that may be associated with hypoxia inducible factors (HIF). The connection between hypoxia signaling, HIF1α, and the circadian clock is well-established (see[69] for review). Likewise, growing evidence supports a role for HIF signaling in diabetic kidney disease[70–72]. Indeed, as shown in Figure 2, HIF1α is a clear example of a clock-controlled gene in the kidney (data derived from CircaDB[73]). It is therefore tempting to speculate that loss or dysregulation of clock-mediated control of HIF1α function may be related to development of DKD.

Figure 2.

HIF1a expression in the kidney exhibits a circadian rhythm. Data derived from CircaDB [73]

We queried whether other genes, which were linked to DKD via genome wide association studies, are themselves circadian clock target genes, similar to HIF1α. Based on recent evidence [74] [75], we selected several DKD genes and queried CircaDB as well as available transcriptomic data [28][17][22], to look for evidence of circadian rhythmicity. Several genes met this criteria: as discussed above, uromodulin fits in this category since it is a BMAL1 target gene[28] and is also associated with kidney disease in Type 1[76] and Type 2 diabetics [24]. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) is a well-established circadian clock target gene (CircaDB) and polymorphisms in this gene are associated with DKD development in Type 2 diabetics[77]. Another interesting link between circadian rhythms and DKD susceptibility genes is Slc12a3, encoding the NaCl cotransporter, which has been linked to DKD[75] and the clock [41, 42, 17].

Summary and Future Directions

It is clear that the circadian clock, both extrinsic and intrinsic to the kidney, is a key regulator of renal function. Thousands of genes and proteins are under the regulation of the molecular clock mechanism and this likely underlies the known circadian variation to several aspects of renal function. It is less clear what happens to the circadian clock within and outside the kidney in pathophysiological states. Available evidence demonstrates that glucose homeostasis, pro-fibrotic mechanisms, and hypoxia signaling are all subject to regulation by the circadian clock, making these likely suspects for mediating a possible link between circadian rhythm dysregulation and DKD. Future work should be aimed at understanding whether the clock can be manipulated by pharmacologic or behavioral means in order to improve outcomes in DKD.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Olanrewaju A. Olaoye, Sarah H. Masten, Rajesh Mohandas, and Michelle L. Gumz declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

REFERENCES

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance •• Of major Importance

- 1.Dibner C, Schibler U, Albrecht U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annual review of physiology. 2010;72:517–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atger F, Mauvoisin D, Weger B, Gobet C, Gachon F. Regulation of Mammalian Physiology by Interconnected Circadian and Feeding Rhythms. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2017;8:42. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meszaros K, Pruess L, Szabo AJ, Gondan M, Ritz E, Schaefer F. Development of the circadian clockwork in the kidney. Kidney international. 2014;86(5):915–22. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazzoccoli G, Francavilla M, Giuliani F, Aucella F, Vinciguerra M, Pazienza V et al. Clock gene expression in mouse kidney and testis: analysis of periodical and dynamical patterns. Journal of biological regulators and homeostatic agents. 2012;26(2):303–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu T, Ni Y, Dong Y, Xu J, Song X, Kato H et al. Regulation of circadian gene expression in the kidney by light and food cues in rats. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2010;298(3):R635–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00578.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang R, Lahens NF, Ballance HI, Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: implications for biology and medicine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(45):16219–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408886111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panda S, Antoch MP, Miller BH, Su AI, Schook AB, Straume M et al. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell. 2002;109(3):307–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storch KF, Lipan O, Leykin I, Viswanathan N, Davis FC, Wong WH et al. Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart. Nature. 2002;417(6884):78–83. doi: 10.1038/nature744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koopman MG, Koomen GC, Krediet RT, de Moor EA, Hoek FJ, Arisz L. Circadian rhythm of glomerular filtration rate in normal individuals. Clinical science (London, England : 1979). 1989;77(1):105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koopman MG, Krediet RT, Koomen GC, Strackee J, Arisz L. Circadian rhythm of proteinuria: consequences of the use of urinary protein:creatinine ratios. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 1989;4(1):9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voogel AJ, Koopman MG, Hart AA, van Montfrans GA, Arisz L. Circadian rhythms in systemic hemodynamics and renal function in healthy subjects and patients with nephrotic syndrome. Kidney international. 2001;59(5):1873–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590051873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firsov D, Bonny O. Circadian rhythms and the kidney. Nature reviews Nephrology. 2018;14(10):626–35. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solocinski K, Holzworth M, Wen X, Cheng KY, Lynch IJ, Cain BD et al. Desoxycorticosterone pivalate-salt treatment leads to non-dipping hypertension in Per1 knockout mice. Acta physiologica (Oxford, England). 2017;220(1):72–82. doi: 10.1111/apha.12804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douma LG, Holzworth MR, Solocinski K, Masten SH, Miller AH, Cheng KY et al. Renal Na-handling defect associated with PER1-dependent nondipping hypertension in male mice. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2018;314(6):F1138–f44. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00546.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solocinski K, Richards J, All S, Cheng KY, Khundmiri SJ, Gumz ML. Transcriptional regulation of NHE3 and SGLT1 by the circadian clock protein Per1 in proximal tubule cells. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2015;309(11):F933–42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00197.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stow LR, Richards J, Cheng KY, Lynch IJ, Jeffers LA, Greenlee MM et al. The circadian protein period 1 contributes to blood pressure control and coordinately regulates renal sodium transport genes. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979). 2012;59(6):1151–6. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.112.190892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards J, Ko B, All S, Cheng KY, Hoover RS, Gumz ML. A role for the circadian clock protein Per1 in the regulation of the NaCl co-transporter (NCC) and the with-no-lysine kinase (WNK) cascade in mouse distal convoluted tubule cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(17):11791–806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.531095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokonami N, Mordasini D, Pradervand S, Centeno G, Jouffe C, Maillard M et al. Local renal circadian clocks control fluid-electrolyte homeostasis and BP. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2014;25(7):1430–9. doi: 10.1681/asn.2013060641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hara M, Minami Y, Ohashi M, Tsuchiya Y, Kusaba T, Tamagaki K et al. Robust circadian clock oscillation and osmotic rhythms in inner medulla reflecting cortico-medullary osmotic gradient rhythm in rodent kidney. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):7306. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07767-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salhi A, Centeno G, Firsov D, Crambert G. Circadian expression of H,K-ATPase type 2 contributes to the stability of plasma K(+) levels. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2012;26(7):2859–67. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-199711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pouly D, Chenaux S, Martin V, Babis M, Koch R, Nagoshi E et al. USP2–45 Is a Circadian Clock Output Effector Regulating Calcium Absorption at the Post-Translational Level. PloS one. 2016;11(1):e0145155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuber AM, Centeno G, Pradervand S, Nikolaeva S, Maquelin L, Cardinaux L et al. Molecular clock is involved in predictive circadian adjustment of renal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(38):16523–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904890106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pradervand S, Zuber Mercier A, Centeno G, Bonny O, Firsov D. A comprehensive analysis of gene expression profiles in distal parts of the mouse renal tubule. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2010;460(6):925–52. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0863-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prudente S, Di Paola R, Copetti M, Lucchesi D, Lamacchia O, Pezzilli S et al. The rs12917707 polymorphism at the UMOD locus and glomerular filtration rate in individuals with type 2 diabetes: evidence of heterogeneity across two different European populations. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(10):1718–22. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahluwalia TS, Lindholm E, Groop L, Melander O. Uromodulin gene variant is associated with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J Hypertens. 2011;29(9):1731–4. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328349de25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleyer AJ, Kmoch S. Tamm Horsfall Glycoprotein and Uromodulin: It Is All about the Tubules! Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(1):6–8. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12201115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynn KL, Shenkin A, Marshall RD. Factors affecting excretion of human urinary Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein. Clin Sci (Lond). 1982;62(1):21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikolaeva S, Ansermet C, Centeno G, Pradervand S, Bize V, Mordasini D et al. Nephron-Specific Deletion of Circadian Clock Gene Bmal1 Alters the Plasma and Renal Metabolome and Impairs Drug Disposition. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(10):2997–3004. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015091055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quigley R, Baum M, Reddy KM, Griener JC, Falck JR. Effects of 20-HETE and 19(S)-HETE on rabbit proximal straight tubule volume transport. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2000;278(6):F949–53. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.6.F949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossier BC, Baker ME, Studer RA. Epithelial sodium transport and its control by aldosterone: the story of our internal environment revisited. Physiological reviews. 2015;95(1):297–340. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurwitz S, Cohen RJ, Williams GH. Diurnal variation of aldosterone and plasma renin activity: timing relation to melatonin and cortisol and consistency after prolonged bed rest. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 2004;96(4):1406–14. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00611.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doi M, Takahashi Y, Komatsu R, Yamazaki F, Yamada H, Haraguchi S et al. Salt-sensitive hypertension in circadian clock-deficient Cry-null mice involves dysregulated adrenal Hsd3b6. Nature medicine. 2010;16(1):67–74. doi: 10.1038/nm.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richards J, Cheng KY, All S, Skopis G, Jeffers L, Lynch IJ et al. A role for the circadian clock protein Per1 in the regulation of aldosterone levels and renal Na+ retention. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2013;305(12):F1697–704. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00472.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gumz ML, Stow LR, Lynch IJ, Greenlee MM, Rudin A, Cain BD et al. The circadian clock protein Period 1 regulates expression of the renal epithelial sodium channel in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119(8):2423–34. doi: 10.1172/jci36908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gumz ML, Cheng KY, Lynch IJ, Stow LR, Greenlee MM, Cain BD et al. Regulation of alphaENaC expression by the circadian clock protein Period 1 in mpkCCD(c14) cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2010;1799(9):622–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richards J, Jeffers LA, All SC, Cheng KY, Gumz ML. Role of Per1 and the mineralocorticoid receptor in the coordinate regulation of alphaENaC in renal cortical collecting duct cells. Frontiers in physiology. 2013;4:253. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richards J, Welch AK, Barilovits SJ, All S, Cheng KY, Wingo CS et al. Tissue-specific and time-dependent regulation of the endothelin axis by the circadian clock protein Per1. Life sciences. 2014;118(2):255–62. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castelo-Szekely V, Arpat AB, Janich P, Gatfield D. Translational contributions to tissue specificity in rhythmic and constitutive gene expression. Genome biology. 2017;18(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1222-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jouffe C, Cretenet G, Symul L, Martin E, Atger F, Naef F et al. The circadian clock coordinates ribosome biogenesis. PLoS biology. 2013;11(1):e1001455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atger F, Gobet C, Marquis J, Martin E, Wang J, Weger B et al. Circadian and feeding rhythms differentially affect rhythmic mRNA transcription and translation in mouse liver. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(47):E6579–88. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515308112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Susa K, Sohara E, Isobe K, Chiga M, Rai T, Sasaki S et al. WNK-OSR1/SPAK-NCC signal cascade has circadian rhythm dependent on aldosterone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427(4):743–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ivy JR, Oosthuyzen W, Peltz TS, Howarth AR, Hunter RW, Dhaun N et al. Glucocorticoids Induce Nondipping Blood Pressure by Activating the Thiazide-Sensitive Cotransporter. Hypertension. 2016;67(5):1029–37. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. ●●.Robles MS, Humphrey SJ, Mann M. Phosphorylation Is a Central Mechanism for Circadian Control of Metabolism and Physiology. Cell metabolism. 2017;25(1):118–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The results of this important work provide clear evidence linking rhythms in tissue oxygenation, including the kidney, to the circadian clock mechanism.

- 44.Adamovich Y, Ladeuix B, Golik M, Koeners MP, Asher G. Rhythmic Oxygen Levels Reset Circadian Clocks through HIF1alpha. Cell metabolism. 2017;25(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walton ZE, Patel CH, Brooks RC, Yu Y, Ibrahim-Hashim A, Riddle M et al. Acid Suspends the Circadian Clock in Hypoxia through Inhibition of mTOR. Cell. 2018;174(1):72–87.e32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peschke E, Bahr I, Muhlbauer E. Experimental and clinical aspects of melatonin and clock genes in diabetes. Journal of pineal research. 2015;59(1):1–23. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stenvers DJ, Scheer F, Schrauwen P, la Fleur SE, Kalsbeek A. Circadian clocks and insulin resistance. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soltesova D, Monosikova J, Koysova L, Vesela A, Mravec B, Herichova I. Effect of streptozotocin-induced diabetes on clock gene expression in tissues inside and outside the blood-brain barrier in rat. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes : official journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association. 2013;121(8):466–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1349123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Angelousi A, Kassi E, Nasiri-Ansari N, Weickert MO, Randeva H, Kaltsas G. Clock genes alterations and endocrine disorders. European journal of clinical investigation. 2018;48(6):e12927. doi: 10.1111/eci.12927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woon PY, Kaisaki PJ, Braganca J, Bihoreau MT, Levy JC, Farrall M et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like (BMAL1) is associated with susceptibility to hypertension and type 2 diabetes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(36):14412–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703247104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. ●.Strohmaier S, Devore EE, Zhang Y, Schernhammer ES. A Review of Data of Findings on Night Shift Work and the Development of DM and CVD Events: a Synthesis of the Proposed Molecular Mechanisms. Current diabetes reports. 2018;18(12):132. doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-1102-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This critical review article incorporates several meta-analyses to support the thesis that shift work and behavioral traits associated with circadian disruption offer unique intervention options in the treatment of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

- 52.Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, Buhr ED, Kobayashi Y, Su H, Ko CH et al. Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes. Nature. 2010;466(7306):627–31. doi: 10.1038/nature09253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. ●●.Hou T, Su W, Guo Z, Gong MC. A Novel Diabetic Mouse Model for Real-Time Monitoring of Clock Gene Oscillation and Blood Pressure Circadian Rhythm. Journal of biological rhythms. 2018:748730418803719. doi: 10.1177/0748730418803719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This important study establishes a novel model for combining the study of diabetic complications with circadian biology.

- 54.Su W, Xie Z, Guo Z, Duncan MJ, Lutshumba J, Gong MC. Altered clock gene expression and vascular smooth muscle diurnal contractile variations in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2012;302(3):H621–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00825.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Su W, Guo Z, Randall DC, Cassis L, Brown DR, Gong MC. Hypertension and disrupted blood pressure circadian rhythm in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2008;295(4):H1634–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00257.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cooper ME. Interaction of metabolic and haemodynamic factors in mediating experimental diabetic nephropathy. Diabetologia. 2001;44(11):1957–72. doi: 10.1007/s001250100000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolf G. New insights into the pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy: from haemodynamics to molecular pathology. European journal of clinical investigation. 2004;34(12):785–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martini S, Eichinger F, Nair V, Kretzler M. Defining human diabetic nephropathy on the molecular level: integration of transcriptomic profiles with biological knowledge. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2008;9(4):267–74. doi: 10.1007/s11154-008-9103-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR, McCullough PA, Roberts T, McFarlane SI, Chen SC et al. Diabetes mellitus and CKD awareness: the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2009;53(4 Suppl 4):S11–21. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matovinovic MS. 1. Pathophysiology and Classification of Kidney Diseases. Ejifcc. 2009;20(1):2–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Navarro-Gonzalez JF, Mora-Fernandez C, Muros de Fuentes M, Garcia-Perez J. Inflammatory molecules and pathways in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Nature reviews Nephrology. 2011;7(6):327–40. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moore WV, Donaldson DL, Chonko AM, Ideus P, Wiegmann TB. Ambulatory blood pressure in type I diabetes mellitus. Comparison to presence of incipient nephropathy in adolescents and young adults. Diabetes. 1992;41(9):1035–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ayala DE, Moya A, Crespo JJ, Castineira C, Dominguez-Sardina M, Gomara S et al. Circadian pattern of ambulatory blood pressure in hypertensive patients with and without type 2 diabetes. Chronobiology international. 2013;30(1–2):99–115. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.701489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hansen HP, Rossing P, Tarnow L, Nielsen FS, Jensen BR, Parving HH. Circadian rhythm of arterial blood pressure and albuminuria in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney international. 1996;50(2):579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojon A, Fernandez JR. Influence of time of day of blood pressure-lowering treatment on cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2011;34(6):1270–6. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bunger MK, Wilsbacher LD, Moran SM, Clendenin C, Radcliffe LA, Hogenesch JB et al. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell. 2000;103(7):1009–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rudic RD, McNamara P, Curtis AM, Boston RC, Panda S, Hogenesch JB et al. BMAL1 and CLOCK, two essential components of the circadian clock, are involved in glucose homeostasis. PLoS biology. 2004;2(11):e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shimba S, Ogawa T, Hitosugi S, Ichihashi Y, Nakadaira Y, Kobayashi M et al. Deficient of a clock gene, brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1), induces dyslipidemia and ectopic fat formation. PloS one. 2011;6(9):e25231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choudhry H, Harris AL. Advances in Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Biology. Cell metabolism. 2018;27(2):281–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Persson P, Palm F. Hypoxia-inducible factor activation in diabetic kidney disease. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension. 2017;26(5):345–50. doi: 10.1097/mnh.0000000000000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tanaka S, Tanaka T, Nangaku M. Hypoxia and Dysregulated Angiogenesis in Kidney Disease. Kidney diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2015;1(1):80–9. doi: 10.1159/000381515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gunaratnam L, Bonventre JV. HIF in kidney disease and development. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20(9):1877–87. doi: 10.1681/asn.2008070804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pizarro A, Hayer K, Lahens NF, Hogenesch JB. CircaDB: a database of mammalian circadian gene expression profiles. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41(Database issue):D1009–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Zuydam NR, Ahlqvist E, Sandholm N, Deshmukh H, Rayner NW, Abdalla M et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study of Diabetic Kidney Disease in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2018;67(7):1414–27. doi: 10.2337/db17-0914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davoudi S, Sobrin L. Novel Genetic Actors of Diabetes-Associated Microvascular Complications: Retinopathy, Kidney Disease and Neuropathy. Rev Diabet Stud. 2015;12(3–4):243–59. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2015.12.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mollsten A, Torffvit O. Tamm-Horsfall protein gene is associated with distal tubular dysfunction in patients with type 1 diabetes. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2010;44(6):438–44. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2010.504190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Y, Peng W, Zhang X, Qiao H, Wang L, Xu Z et al. The association of ACE gene polymorphism with diabetic kidney disease and renoprotective efficacy of valsartan. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2016;17(3). doi: 10.1177/1470320316666749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]