Abstract

Burnout among behavioral health care providers and employees is associated with poor patient and provider outcomes. Leadership style has generally been identified as a means of reducing burnout, yet it is unclear whether some leadership styles are more effective than others at mitigating burnout. Additionally, behavioral health care is provided in a variety of contexts and a leadership style employed in one context may not be effective in another. The purpose of this paper was to review the literature on leadership style and burnout in behavioral health care contexts to identify the different leadership styles and contexts in which the relationship between the two constructs was studied. Studies were categorized based on the leadership style, study design, research methods, and study context. Findings of this review provide insights into potential approaches to prevent employee burnout and its attending costs, as well as ways to improve future research in this critical area.

Introduction

Behavioral health care disorders, including mental, emotional, and substance use disorders, affect almost 20% of adolescents and adults in the United States (U.S.) and are increasing in prevalence.1 These disorders tend to be high-cost conditions with over $90 billion being spent annually on the diagnosis, treatment, and maintenance of these conditions.2 Due in part to the growing prevalence of behavioral health disorders, their chronic nature, and the type of care needed for patients with these conditions, maintaining a qualified workforce is an ongoing challenge in behavioral health care services. For instance, studies estimate that nearly 50% of behavioral health care providers feel overburdened due to the emotionally taxing nature of the job, high stress levels, perceived lack of career advancement opportunities, and low salaries coupled with high caseloads.3–7 The cumulative result of such prolonged work-related stress is employee burnout.

Burnout has been broadly defined as a complex, psychological syndrome which manifests in response to prolonged exposure to chronic interpersonal stressors.8, 9 Although commonly seen among those in helping professions such as health care, teaching, law enforcement, and social services, a high incidence of burnout can exist in multiple settings and across different professions such as engineering, accounting, and sales.10–13 Employee burnout among behavioral health care workers is associated with a wide range of physical, emotional, and behavioral symptoms at the individual level such as aggressive behavior, physical illness, acts of violence, conflicts at home and the workplace, depression, and higher likelihood of alcohol and substance abuse.14–17 At the organizational level, behavioral health care employee burnout is associated with a deterioration in the quality of care leading to negative clinical outcomes such as low patient satisfaction, poor communication with patients and staff, poor patient engagement, and more errors.18, 19 Outside of clinical care outcomes, burnout has also been linked to negative employee outcomes such as low employee morale, absenteeism, lower organizational commitment, and job turnover,8, 20, 21 all of which ultimately result in higher costs to the individual and the organization. Several studies and reports examining the behavioral health care workforce in the U.S. indicate that there exists a severe shortage of nearly all types of behavioral health care providers (e.g., psychiatrists, clinical and school psychologists, substance abuse counselors, and mental health counselors), and this situation is likely to worsen as the nationwide prevalence of behavioral health disorders increases.22–24 Given the aforementioned issues, there is a growing need to identify ways to prevent or minimize the incidence of employee burnout, particularly within the behavioral health care workforce since they are highly susceptible to it.23

A growing number of studies have considered the protective role of leadership on employee burnout in behavioral health organizations, identifying different leadership styles that can decrease the likelihood of developing burnout.4, 25–28 Leadership style encompasses behavioral patterns and characteristics exhibited by individuals in positions of formal authority to influence others to achieve a common goal.29, 30 Prior studies that have examined the association between leadership style and employee burnout have found that leadership styles characterized by the ability of the leader to engage in clear communication and active listening, empathize with employees and coworkers, adopt compassionate and ethical approaches to problem-solving, and exhibit willingness to accept recommendations are associated with lower incidence of burnout.31–33 Nevertheless, current understanding of the relationship between leadership style and employee burnout is limited by a number of factors that highlight the need for a critical review of this literature. First, there are many different leadership styles (e.g., transformational, transactional, and servant) that encompass a wide range of leader behaviors exhibited by individuals in positions of formal authority. A better understanding of the leadership styles considered in this literature may point to effective approaches and missed opportunities to reduce burnout. Second, behavioral health care services are delivered in a variety of contexts (e.g., organization types, professional groups), and it is not clear that the same leadership style would have the same impact in these different contexts. Third, the evolution of old and introduction of new research methods presents new opportunities to understand the relationship between leadership and burnout, yet it is unknown whether researchers in this area are taking advantage of these opportunities. Given these considerations, the purpose of this paper was to review the extant literature and increase understanding of the current knowledge on leadership styles and employee burnout in behavioral health care settings. The authors aim to do this by addressing the following research questions:

What type of leadership styles have been considered as antecedents of burnout in the behavioral health care literature and in what contexts?

What is the relationship between leadership style and burnout in the behavioral health care setting?

What methodological approaches have been used to study the relationship between leadership style and burnout in behavioral health care settings?

What are the study contexts in which the relationship between leadership style and burnout have been explored?

To the authors’ knowledge, no studies have reviewed the literature on the relationship between leadership style and employee burnout in behavioral health care settings. Even so, this study builds on previous reviews that have examined antecedents to burnout in various medical settings, such as among physicians and nurses in acute care hospitals,34 and nurse practitioners and physician assistants.35 The focus on leadership styles complements other studies that have reviewed antecedents such as organizational climate36, 37 and role characteristics such as role conflict and role ambiguity.38, 39 The authors, submit, however, that apart from the stressors in general medical settings such as time pressure, role conflict, and high caseloads,40 behavioral health care workers face added challenges in the form of inadequate resources from chronic underfunding of the behavioral health safety net, low wages, and poor training and supervision,6, 41 all of which affect recruitment as well as retention of a qualified workforce. Given the worsening behavioral health workforce shortages,23, 24 there is an urgent need to identify different approaches to reduce burnout, one of which may be effective leadership.

The study utilizes a conceptual review approach, an adaptation of a realist review that includes five key steps: (i) identifying the scope, (ii) searching for evidence, (iii) appraisal of primary studies and extraction of data, (iv) synthesis of evidence and drawing of conclusions, and (v) evaluation of findings and recommendations.42–44 Unlike traditional systematic reviews that tend to be more narrow and specific in terms of scope and findings, conceptual reviews provide greater insight into the contextual factors that may influence outcomes. Following the guidelines of the conceptual review, the scope of this review is outlined in the research questions above and further clarified in the analytic framework section below. The “Methods” section provides details on the search strategy, including the specific criteria used for inclusion and exclusion of studies. The findings from each study are then reported in the “Results” section. Finally, a synthesis of the included studies and recommendations for future research are provided in the “Discussion” section. The sections below elaborate on these steps.

Analytic Framework

The studies in this review were classified and analyzed in four ways. First, the authors classified studies based on the dimension of employee burnout identified. Second, the studies were categorized based on the leadership style(s) considered. Third, the authors classified the studies based on the methods used to study the relationship between leadership style and employee burnout. Finally, the authors systematically captured information related to the contexts in which the studies were conducted. The following sections provide more details on this analytic framework.

Burnout

As a psychological response to chronic stressors, burnout is characterized by three distinct but interrelated dimensions, namely, emotional exhaustion, cynicism, or depersonalization, and a perceived lack of personal accomplishment.8, 9 Typically seen as the first sign of burnout, emotional exhaustion refers to the intense feelings of being depleted of physical and emotional resources as a result of an individual’s chronic and sustained exposure to suffering and other stressors. Following prolonged emotional exhaustion and continued exposure to job stressors, the individual develops a sense of cynicism, detachment, or depersonalization from different facets of the job. Finally, as a result of the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, the individual experiences feelings of incompetence or lack of personal achievement at work, characterizing the third dimension of burnout.8, 45, 46 This review distinguished between these three dimensions when coding and synthesizing the literature.

Leadership style

In this review, the authors focused exclusively on leadership styles and not on leader behavior or traits. This decision was motivated by the authors’ interest in understanding the relational impact of leadership on burnout, which is likely to be more modifiable than other potential leadership attributes (e.g., traits). To provide a more complete picture of how the research has examined the relationship between leadership style and burnout, the authors intentionally adopted a broad view of what constitutes leadership in behavioral health organizations by defining leaders to include senior/upper level executives, middle managers, and frontline supervisors. Finally, the authors reviewed the studies to identify the key leadership styles considered, focusing primarily on transformational leadership, transactional leadership, laissez-faire, and servant leadership. Transactional leadership is characterized by contingent reward, active management-by-exception, and passive management-by-exception. Transactional leaders set performance goals, motivate subordinates to perform at expected levels, and enable them to recognize task responsibilities by tying reward and punishment to these responsibilities.30, 47, 48 On the other hand, transformational leadership is characterized by individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, inspirational motivation, and idealized influence,30, 47 all of which connect people to the impact of their work and motivate employees to remain engaged in their tasks. Servant leadership is similar to transformational leadership in that it places a high emphasis on integrity, compassion, and ethical work from employees and leaders; however, the key differences between the two leadership styles pertain to the focus of the leaders and the nature of the leader-follower relationship.49 Contrary to these aforementioned leadership styles, laissez-faire leadership represents a missing or absent leadership style, where the leader may physically occupy the leadership position, but has abandoned all duties and responsibilities associated with the leadership role. Laissez-faire leaders are rarely involved with employees and followers, do not provide any feedback or rewards, and make no effort to motivate employees or recognize their needs.50 In addition to these leadership styles, the authors also considered any additional styles included in the reviewed studies.

Research methods

A better understanding of the research methods used to study the relationship between leadership style and employee burnout in behavioral health organizations is important for assessing how much confidence can be placed in published findings, as a whole, and what methodological improvements may exist to extend understanding of this phenomenon. Therefore, this review captured a number of methodological details. First, the studies were classified according to whether they were cross-sectional or longitudinal. Second, studies were classified as qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods. Both of these study design elements are important considerations when trying to understand how researchers have tried to examine whether and how a multilevel, relational factor like leadership style may influence a cognitive, process-based phenomenon like burnout. Similarly, it is important to consider how data are collected to assess their appropriateness and how those data collection efforts may affect the study findings. Therefore, the sample size of each study was recorded and studies were classified as collecting data via surveys, interviews, focus groups, administrative data, or some combination of these approaches.

Context

The final dimension of this review was the context in which researchers have examined the relationship between leadership and burnout. Context can be defined as the stimuli and phenomena that surround an individual, typically at a different level of analysis, e.g., team, family, organization, or community.51 Different relationships may emerge across different contexts for several reasons, such as the applicability of certain leadership styles in different organizational settings. For example, transactional leadership may not be as effective in large hospitals where behavioral health services represent but one piece of the overall service portfolio. Regardless, greater attention to these aspects of a research study can help assess whether leadership styles are more effective at reducing burnout in some contexts and not others, or perhaps, whether some leadership styles are effective regardless of context.

Unfortunately, detailed frameworks for assessing the myriad of factors that make up context are lacking. Therefore, following Johns (2006), the 5 W’s (who, what, when, were, and why) were used to examine the contextual features of the studies. The questions of “what” (i.e., the relationship of interest) and “why” (i.e., the purpose or motivation for the study) are addressed by our second research question—What is the relationship between leadership style and burnout in the behavioral health care setting?. Therefore, contextual considerations were limited to questions of “when,” “where,” and “who.” “Who” refers to the occupational and demographic characteristics of the study subjects. “When” refers to the time (e.g., year) the study was conducted. “Where” refers to the study setting (e.g., organization type, country, urban, or rural).

Method

Search strategy

In order to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature, five electronic databases, PubMed, CINAHL, ABI/Inform, PsycINFO, and PsycARTICLES, were searched between November and December 2017 to identify eligible studies related to leadership style and employee burnout in behavioral health care organizations. Keeping in mind the growing interest in behavioral health disorders and the authors’ goal of providing recommendations based on the most recent research, the searches were limited to articles published within the past 20 years (1997–2017). The search terms included combinations of the words “burnout,” “compassion fatigue,” “occupational stress,” “workplace stress,” “leadership,” “leadership styles,” and “management styles.”

Inclusion–exclusion criteria

The search was limited to empirical studies published in English language peer-reviewed journals. Studies were included in the review if they exclusively focused on organizations treating behavioral health disorders, including substance abuse treatment centers, mental health agencies, psychiatric hospitals, and inpatient psychiatric units within acute care hospitals. Studies conducted within other healthcare facilities were excluded if they did not include a behavioral health component. Studies were also excluded from the review if they did not examine burnout or one of its immediate organizational consequences such as turnover intentions or turnover52 and leadership in a behavioral health context. For example, a study by Sellgren et al. (2007) that examined the relationship between leadership and burnout was excluded because the study was not conducted in a behavioral health provider organization. Likewise, a study by Luther et al. (2017) assessed the impact of working overtime on burnout among clinicians working in community mental health clinics, but was excluded from the review because it did not include an examination of leadership style.

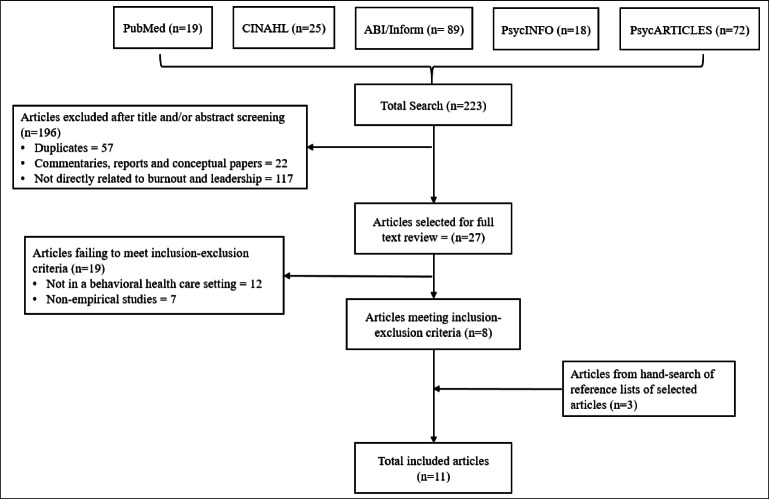

The searches yielded 223 articles across the selected databases, including duplicates. After eliminating duplicate studies, gray literature, and non-empirical studies, 27 articles were selected for full-text review. The inclusion–exclusion criteria were applied to these 27 articles, of which eight (8) were selected to be included in the review. The reference list of the selected 8 articles were further searched for relevant studies, and three (3) additional articles were identified, yielding 11 articles to be included in this review. A summary of the study selection process is shown in Fig. 1 in the Appendix.

Fig. 1.

Article selection process

Article coding and data extraction

All 11 articles were read in full by the first author and were coded according to the analytic framework. The second author independently reviewed the same 11 articles and coded the articles using the same framework to assess the accuracy and consistency of the coding scheme. Interrater agreement was assessed using Cohen’s kappa statistic,53 which in this case measured how frequently both authors assigned a study to the same analytic category (e.g., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal study). Kappa statistics were individually estimated for all dimensions of the analytic framework that used a nominal category, including whether to include the study in the review, study design, leadership styles considered, and dimensions of burnout examined, and ranged from 0.82 to 1.00 (p < .01 in all cases), indicating substantial to perfect agreement.53, 54 For other dimensions that were more qualitative, discrepancies were discussed and the coding categories were refined based on these discussions (e.g., capturing more detail on the study samples).

Results

Burnout

Over two-thirds (8 of 11) of the reviewed studies measured all three dimensions of burnout (Table 1). Two studies used a “global” measure of burnout,55, 56 an aggregation of the individual subscales that reflect the three dimensions of burnout. One of these studies, however, also examined the individual dimensions of burnout.55 One study examined only emotional exhaustion and depersonalization,57 while another study focused only on emotional exhaustion.58 This latter study is noteworthy because it examined the moderational influence of transformational leadership on the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention.

Table 1.

Summary of literature on burnout and leadership style

| Why? | Where? | Who? | When? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors (year published) | Study aim | Setting | Subjects/sample size | Year study conducted | Outcome | Leadership style | Key findings |

| (Webster & Hackett, 1999) | This study investigated whether specific components of burnout in clinical staff in community mental health agencies was related to aspects of leadership behavior and quality of supervision of clinical supervisors. | Community mental agencies | 151 clinicians | Not specified | Staff burnout (all three dimensions) | None explicitly stated, but items in the Leadership Practices Inventory Scale (LPI) correspond to transformational leadership |

(i) Leadership style and supervisor rating were inversely related to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization components of burnout, (ii) No relationship between personal accomplishment and leader behavior. |

| (Corrigan et al., 2002) | This study examines the relationship between transformational, transactional and laissez-faire leadership styles and measures of organizational culture and staff burnout in mental health services teams. | Mental health teams in state hospitals and community mental health programs | 236 leaders; 630 subordinates | Not specified | Staff burnout (all three dimensions) |

(i) Transformational leadership (ii) Transactional leadership (iii) Laissez-faire leadership |

(i) Leaders who saw themselves as transformational also saw their organizational culture as cohesive and transformational. (ii) Subordinates who viewed their organizational culture as transformational also viewed their leaders as charismatic and transformational, but those who viewed their culture as transactional were less likely to rate their leaders as charismatic. (iii) Leader and subordinate responses showed that burnout was negatively associated with transformational and charismatic leadership. |

| (Kanste et al., 2007) | The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between multidimensional leadership and burnout among nursing staff. | Health care organizations, including psychiatric hospitals | 601 nurses | 2001-2002 | Staff burnout (all three dimensions) |

(i) Transformational leadership (ii) Transactional leadership (iii) Laissez-faire leadership |

(i) Rewarding transformational leadership was negatively correlated with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (ii) Passive laissez-faire leadership negatively related to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. (iii) Active management-by-exception positively correlated with personal accomplishment. (iv) Passive laissez-faire leadership associated with emotional exhaustion in temporary nurses, rewarding transformational leadership protects temporary nursing staff from emotional exhaustion. |

| (Broome et al., 2009) | This study explores counselor views and the impact of organizational context in outpatient drug-free treatment centers. | Outpatient drug-free treatment centers | 550 counselors and directors | 2004-2005 | Counselor’s perceptions of burnout, leadership, and job satisfaction | None explicitly stated. Survey of organizational functioning (SOF) tool used in the study includes measures of transactional and transformational leader behaviors. |

(i) Leadership was significantly negatively related to burnout. (ii) Director leadership was a protective factor in the relationship between counselor caseload and burnout. |

| (Crawford et al., 2010) | The purpose of this study is to examine levels of burnout among staff working in community-based services for people with personality disorder (PD) and to explore factors which add to or lower the risk of burnout among people working in such services | Community-based treatment centers for people with personality disorders. | 89 workers from 11 centers | Not specified | Staff burnout (all three dimensions) | None explicitly stated |

(i) Teamwork and leadership support are essential to maintain good working conditions and support for staff. (ii) The best leadership style was dependent on the nature and needs of client and staff groups. (iii) External supervision essential for the team success. |

| (Aarons et al., 2011) | This study examined leadership, organizational climate, staff turnover intentions, and voluntary turnover during a large-scale statewide behavioral health system reform | Behavioral health agencies under safety net institutions | 190 participants from 14 agencies | 2006-2007 | Voluntary turnover | Transformational leadership |

(i) There was a negative relationship between transformational leadership and demoralizing organizational climate in high stress organizations. (ii) Relationship between transformational leadership and turnover intentions were fully mediated by empowering climate. (iii) There was a positive relationship between turnover intentions and voluntary turnover. |

| (Green et al., 2013) | The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between transformational leadership, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intentions among public sector mental health care providers | Public sector mental health programs for children, adolescents, and families | 388 community mental health providers | Not specified | Emotional exhaustion, turnover intentions | Transformational leadership |

(i) Emotional exhaustion was significantly associated with turnover intention. (ii) Controlling for emotional exhaustion, the relationship between transformational leadership and turnover intentions became non-significant. (iii) Transformational leadership moderated the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention. |

| (Green et al., 2014) | This study examines the influence of demographics, work characteristic, and organizational variables on levels of burnout among child and adolescent mental health service providers operating within a public sector mental health service system | Public sector mental health programs | 322 clinical and case management providers | Not specified | Staff burnout | Transformational leadership |

(i) Leadership and organizational variables had significant moderate to large correlations with burnout. (ii) Higher levels of transformational leadership was associated with greater personal accomplishment. |

| (Madathil et al., 2014) | This study examined the relationships between leadership style of psychiatric nurse supervisors, work role autonomy, and psychological distress in relation to psychiatric nurse burnout | Hospitals in the New York State Office for Mental Health and one psychiatric hospital in a different state | 89 nurses | 2009-2010 | Staff burnout | Transformational leadership |

(i) Autonomy and transformational leadership were significantly negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and significantly positively associated with personal accomplishment. (ii) Transformational leadership is a significant mediator of the relationship between depressive symptoms and personal accomplishment. (iii) Moderating relationship of workload on transformational leadership and autonomy, and burnout was not statistically significant. |

| (Bijari & Abassi, 2016) | The aim of this study is to determine the prevalence of burnout and associated factors among rural health workers in the health centers of Iran | Public Health Centers (PHCs) providing a range of primary care services, including mental health and occupational health services | 423 rural health workers | 2012-2013 | Staff burnout | None explicitly stated |

(i) High stress and dissatisfaction from poor supervisor oversight were associated with burnout. (ii) Burnout was more prevalent in this study than in prior studies conducted in the region. |

| (Yanchus et al., 2017) | This study examined predictors of turnover intention or an employee’s cognitive withdrawal from their job, in a large sample of direct care mental health professionals | Veteran’s Administration | 10,997 mental health employees | 2013 | Emotional exhaustion, turnover intentions, turnover plans | None explicitly stated |

(i) Supervisory support and job satisfaction were negatively related to emotional exhaustion. (ii) Job satisfaction and supervisory support negatively related to turnover plans. (iii) Emotional exhaustion significantly positively associated with turnover intentions. |

Leadership style

This review found that transformational leadership was considered more frequently in the literature on burnout in behavioral health care settings than any other leadership style. Four (4) of the 11 reviewed studies57–60 exclusively focused on the impact of transformational leadership on burnout. Two additional studies25, 26 compared transformational leadership with other leadership styles, including laissez-faire and transactional leadership, while the remaining five articles4, 55, 56, 61, 62 simply examined the impact of leadership (“none explicitly stated”) on burnout and turnover without describing or designating it as a particular style.

Associations between leadership style and burnout

The results of this review suggest that transformational leadership, in general, was negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and positively associated with personal accomplishment. Specifically, six of the 11 studies (54.5%) that included transformational leadership found it to be significantly associated with lower levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.25, 26, 57–60 Similarly, three of the studies that considered transformational leadership found significant associations with greater levels of personal accomplishment. These findings are consistent with the extant literature in other organizational contexts.28, 63–65 Notably, however, two studies (18%) found that transformational leadership was not significantly associated with personal accomplishment or depersonalization.

Of the two studies that examined the association between transactional leadership and burnout,25, 26 both reported a significant positive association between emotional exhaustion and transactional leadership, while two additional studies58, 62 did not measure all dimensions of burnout. Additionally, even though most of the research focused on transformational leadership, active management-by-exception, a component of transactional leadership, was found to have a similar negative effect on burnout as transformational leadership.26 Five of the reviewed studies did not examine any particular leadership style in their study of burnout (indicated as “none explicitly stated”) and simply focused on the role, oversight, and support from supervisors. These studies found that more positive perceptions of leadership (e.g., supervisor support) were significantly associated with lower levels of burnout, particularly emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.

Study design and methods

Of the 11 empirical studies included in this review, all employed a cross-sectional design. Except for one study that used a mixed methods approach,61 the others relied on quantitative analyses conducted on primary data collected in the form of respondent surveys. Sample sizes in the reviewed studies ranged from 8960, 61 to nearly 11,000 subjects.62 Study designs are tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of study design

| Total | % of total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal design | Cross-sectional | 11 | 100 |

| Longitudinal | 0 | 0 | |

| Type of data | Quantitative | 10 | 90.9 |

| Qualitative | 0 | 0 | |

| Mixed methods | 1 | 9.01 |

Context: where?

About one-half (5 of 11) of the studies included mental health teams or community mental health organizations.4, 25, 57–59, 61 Two studies were conducted in substance abuse treatment facilities,56, 57 and another two were conducted in psychiatric hospitals or psychiatric units within general acute care hospitals.26, 60 Only two studies included a mixture of settings in the same study.25, 57

Who?

Similar to the study settings, the subjects of the studies varied widely, both within and across studies. For example, Webster and Hackett (1999) included nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers. In contrast, Madathil and colleagues (2014) and Kanste, Kyngas, and Nikkila (2007) focused exclusively on nurses. Among the five studies that included multiple occupational groups, slightly more than half (3 of 5) controlled for differences in burnout between these groups, an ostensibly important consideration given that these studies found significant differences between the groups.4, 59, 62 Only two of the reviewed studies explicitly described including both leaders/supervisors and providers/staff in the study.56, 58

When?

Over one-half (6 of 11) of the reviewed studies did not specify when the study was conducted. Of the five that did specify, two were conducted in the past five years55, 62 and another was conducted in the past decade.60

Discussion and Research Recommendations

Providers in behavioral health treatment settings face a high risk of burnout due to the demanding nature of their job, including high caseload, poor career advancement opportunities, and low financial compensation.3, 5, 6, 23, 41 Additionally, these providers interact daily with patients who may exhibit aggressive, violent, and suicidal behavior, exacerbating the experiences of work-related stress and compassion fatigue.61 Of the various antecedents of employee burnout, the role of leadership has been extensively discussed. The purpose of this study was to review the literature that has examined the relationship between leadership style and burnout in different behavioral health care contexts. The following sections put the findings of this review in context of other research on burnout while making recommendations for funders and researchers who are interested in extending this work.

Leadership style

The findings of this review are consistent with those conducted within other healthcare organizations, recognizing the direct and indirect role of transformational leadership in reducing the likelihood of burnout. The lack of a significant association between transformational leadership and all three dimensions of burnout in the studies reviewed by the authors,4, 60 however, is particularly notable because prior studies that have established a negative association between transformational leadership and burnout have not consistently made it explicit whether this impact was related to emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, or personal accomplishment. Based on the findings of this review, generalizations about the effects of transformational leadership (and likely other types of leadership) should be made cautiously and reflect distinctions between the dimensions of burnout.

It is also notable that most of the studies in this review examined the presence and extent of transformational leadership in mitigating burnout, with little effort to explore other leadership styles, including and especially direct comparisons of leadership styles. Consequently, relatively little is known about the comparative advantages of leadership styles when it comes to burnout. Of the studies that compared the effects of transactional, laissez-faire, and transformational leadership on burnout, the results were consistent in that laissez-faire leadership and passive management-by-exception were associated with greater emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lower personal accomplishment. However, this review found that transactional leadership, in the form of contingent rewards and active management-by-exception, can have similar effects on burnout as transformational leadership, implying that there is a need for research in the behavioral health context to extend beyond transformational leadership. This leads to the first research recommendation.

Recommendation 1: Explore the role of other leadership styles on burnout

Although some studies found empirical support for the role of transformational leadership and some types of transactional leadership in reducing burnout, this was not the case for all studies. Moreover, without much consideration of other leadership styles, it is difficult to ascertain whether transformational and some transactional leaders “outperform” other types of leaders, at least with respect to employee burnout. Therefore, there is value in considering the role of additional leadership styles that focus more on the employee and their well-being rather than the task alone. Among the various leadership styles that have shown to demonstrate success in service organizations, servant leadership has gained tremendous popularity in recent years due to its focus on employees in the organization. Originally introduced by Greenleaf (1977), servant leadership has broad similarities with transformational leadership in terms of motivation of followers, vision, respect, and integrity.66 However, the difference between the two lies in the focus of the leader, where transformational leaders primarily focus on the organization as a whole, servant leaders focus most importantly on people within the organization.49 In a comparison between the two leadership styles, servant leadership has been found to be a better predictor of organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in service-based jobs.67 Additionally, studies have also suggested that when studying organizational outcomes such as organizational citizenship behavior, trust and commitment, it may be beneficial to explore the role of servant leadership rather than limit research to previously explained leadership styles and models.67–69 Given these considerations, future studies on burnout should consider exploring the role of servant leadership on employee burnout.

Along similar lines, it should also be recognized that leadership styles are theoretical constructs that represent an amalgamation of different individual behaviors. While consolidating these individual behaviors into different leadership styles can help to improve current understanding on how these behavioral characteristics, in aggregate, may affect employee burnout, in doing so, there is also a risk of overlooking the more granular effects of specific behaviors that need to be encouraged or discouraged to prevent employee burnout. Thus, future research may want to consider whether specific leadership behaviors are more impactful than others at reducing employee burnout among behavioral health care employees.

From a leadership training perspective, organizations might find it beneficial to include elements of transformation, transactional, and servant leadership styles to their leadership training initiatives.68 This integrated approach may allow organizations to provide emergent leaders with the necessary tools to address issues related to employee psychological well-being that can further impact individual and organizational-level outcomes, particularly in behavioral health care settings. Similarly, to the extent that specific behaviors can be identified as effective at reducing employee burnout, leadership training initiatives that focus on cultivating these behaviors may provide a more focused approach for organizations to reduce employee burnout.

Study methods

With regard to the study design and methods, all of the studies included in this review were cross-sectional in design, with 10 out of 11 studies relying purely on quantitative analyses. Despite self-acknowledged limitations of cross-sectional study designs that preclude conclusions regarding causality, no longitudinal studies have been conducted over the years to overcome this limitation and to examine the short-, intermediate-, and long-term impact of leadership on burnout. Additionally, even though there are well-established limitations to relying only on quantitative methods,70, 71 only one study attempted to use a mixed methods research design, using data from structured interviews as well as surveys. These findings highlight significant gaps in the methodological designs of existing studies that examine the impact of leadership on burnout in the behavioral health care settings.

Heavy reliance on quantitative, cross-sectional studies can be problematic because they do not shed any light on the sustained influence of leadership on burnout. Additionally, burnout has been described as more of a process that develops over time, passing through various stages,8, 52 and cross-sectional studies fail to capture how burnout may develop, or how and why employees transition from one stage to another. Likewise, data from single point-in-time surveys are able to provide only limited insights into the nuanced differences and relationships between complex multidimensional constructs such as burnout. These deficiencies prompt the second research recommendation.

Recommendation 2: Extend beyond cross-sectional study designs

Inclusion of more qualitative and mixed methods research can enable researchers to better capture the processual and conditional aspects of burnout.70, 72 For example, interviews and focus group meetings may be more helpful in learning in detail from employees about the different contributors to burnout and why they may lead to burnout. Likewise, sequential combinations of qualitative and quantitative research may allow researchers to explore burnout in greater depth, taking organizational context and organizational relationships into account.73 For instance, a quantitative analysis may be helpful in determining the prevalence of burnout for different types of behavioral health care providers, and these results can inform qualitative analyses that examine why some leadership styles are more effective at reducing burnout for some providers and not others. In sum, these approaches can provide richer contextual understanding of the problem for researchers as well as organizational leaders who can then target remedial measures toward specific individuals or teams that are the most susceptible to burnout.

Another approach for extending current understanding of burnout and ways to prevent it is to utilize more longitudinal studies. For example, one of the overall strengths of the reviewed literature was its general consideration of all three dimensions of burnout. Such comprehensive approaches to examining burnout are important given findings that leadership style may have a significant relationship on some dimensions and not others.4, 58 However, the dependence on cross-sectional designs has provided limited understanding of how and why behavioral health care workers progress from one stage of burnout to another. Longitudinal studies can shed light on the theoretically proposed chronological sequence of burnout, thereby improving our understanding of this process. Additionally, longitudinal studies are helpful for examining the impact of changes over time, such as change in leadership practices following leadership training, as well as comparing its relationship to burnout across time periods. Since burnout is a gradually developing process, examining leader and employee behaviors over time may provide more conclusive results on the development of burnout and ways to prevent it.

Context

Behavioral health disorders include a wide range of disorders, ranging from mental and emotional disorders to substance abuse. Consequently, there is great variety in the settings in which behavioral health programs and services are delivered as well as the professionals who provide them. Therefore, it was not entirely surprising to find a wide range of settings and professionals in the studies reviewed. What is notable, however, is that very few studies included multiple types of behavioral health organizations or occupational groups in the same study. Consequently, it is difficult to directly compare the relationships between different contexts. Of the studies that did include multiple types of organizations/settings or occupational groups, the studies consistently found significant differences,4, 59 underscoring the importance of considering context. Similarly, slightly more than half of the reviewed studies reported the time when the studies were conducted, a potentially important consideration when assessing the state of literature. While publication dates can sometimes be used as a proxy for when a study was conducted, more thorough reporting of when a study was conducted becomes critical in other types of study designs (e.g., longitudinal and mixed methods) should researchers follow through on the authors’ recommendation to adopt more of these designs. In sum, consistent with other reviews of context,74 the analysis presented here suggests that context is often neglected or, when considered, typically relegated to secondary importance, something to be “controlled for” rather than being of substantive interest in its own right. This neglect is unfortunate as context can have a number of consequences for analyses, including restricting the range of observable phenomena (e.g., realistic effect of leadership on burnout), affect base rates of burnout, change the causal direction of relationships (e.g., high levels of burnout leads organizational leaders to adopt different approaches), or condition the strength of the observed relationship (e.g., low and high levels of certain types of leadership may be associated with high levels of burnout while intermediate levels are associated with low levels).74

Recommendation 3: Pursue studies that promote a better appreciation of context

The importance of context has gained momentum in recent years and a more thorough and explicit consideration of context would strengthen the research agenda on burnout in behavioral health settings.75, 76 There are a number of ways that researchers can more explicitly incorporate context into their work on burnout in behavioral health settings. At a minimum, researchers should provide a thorough description of the context in which their studies are being conducted. By and large, the studies included in this review provided enough detail to code where and who was the focus of the study, but that was not necessarily the case for when the studies were done. Moreover, even amongst studies where sufficient information was available to code where the study was conducted and who was the focus, more nuanced details were often lacking (e.g., profit status, single vs. multi-site facilities).

In addition to richer descriptions of the study settings, researchers may also want to consider moving beyond “controlling for” context and feature it more centrally in their analysis of burnout. In doing so, researchers should recognize that context may act as a main effect or interact with other variables to affect behaviors and outcomes.74 For example, organizational climates that promote autonomy may directly reduce feelings of burnout60 or they may mediate the effects of transformational leadership on burnout.57 However, given its nested nature, it is likely that a more explicit and direct consideration of the role of context will require extending the methodological approaches beyond what is commonly used in this literature. For example, advances in statistical software packages and resources to support their use (e.g., books, websites) have proliferated in the past decade and made these analyses easier to implement. The study by Green et al. (2014) included in this review provides an example of how this can be done. In this study, the authors focused on 322 clinical and case management service providers who were members of 49 mental health clinics that were providing mental health services in San Diego County. Preliminary analysis suggested that between 8 to 14% of the variance in burnout outcomes was accounted for by differences in the mental health clinics (rather than individual provider attributes). Using hierarchical linear models, the authors found that more positive work climates and higher levels of transformational leadership—aggregated to the clinic level—were associated with greater individual perceptions of personal accomplishment, while individual-level variables such as age, gender, and education were generally not associated with any of the three dimensions of burnout. This example demonstrates that the factors that may contribute or prevent burnout do not necessarily operate at a single level of analysis and that multilevel approaches are not only appropriate (e.g., account for correlated errors within nested units), but they can shed light on the multilevel relationships that are endemic to most behavioral health care settings. Likewise, as suggested in the second recommendation, qualitative or mixed methods are also beneficial for understanding more deeply the many layers of context and how it can impact behavioral outcomes such as burnout.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, leadership style is but one of many factors that may be related to the development of employee burnout. Therefore, studies that focus solely on the association between leadership style and burnout may be overstating the extent to which leadership has an association with employee burnout, without taking other factors such as family support, coworker relationships and nature of employee-client relationships, organizational culture, climate, and job characteristics into consideration. Second, the studies in the review did not always distinguish between leadership and supervisory support. Consequently, it was not possible to isolate differences between these two, despite theoretical and empirical reasons to believe their effects on burnout may differ. Finally, although this review was focused on behavioral health workers across various settings, it is important to note that the scope of duties for these providers varies significantly across countries. About a third of the studies in this review were conducted in countries outside of the U.S., where organizational contexts and provider duties differ from those within the U.S. Therefore, the results from the studies conducted outside the U.S. may not be directly comparable with those conducted within the U.S. Nevertheless, given the scarcity of research on this topic in the U.S., the authors felt it was important to include these studies in the review.

Implications for Behavioral Health

Although the scope of this review is narrow in that it focuses specifically on leadership styles and employee burnout within behavioral health care settings, the recommendations made here have broader implications for behavioral health care practitioners, policy makers, and researchers. As acknowledged in the preceding sections, leadership is one of many factors that might play a role in minimizing employee burnout. In addition to the direct associations between leadership style and burnout, studies have also established an indirect association between the two via mediators such as organizational climate,36 work engagement,77 and empowerment.78 Furthermore, leadership style also likely has an association with other antecedents of burnout such as caseload and role expectations since leaders are probably responsible for assigning tasks and setting performance expectations. Thus, behavioral health care leaders would benefit from not only being mindful of the importance of leadership styles and explore characteristics of multiple leadership styles to train upcoming leaders, but should also view leadership style in the larger context of other interrelated factors that might be modified to reduce employee burnout. Additionally, to the extent that published literature acts as a guide for organizational action,79 this critical review of the research methods and its specific recommendations for how to improve these methods will help strengthen the evidence base on which these decisions are made. Finally, the review of the methods used in these studies are likely to be beneficial for other behavioral health researchers in identifying ways to improve future research in this area.

Conclusions

Unlike other healthcare settings, behavioral health providers face unique challenges that place them at a greater risk of experiencing burnout. While the literature consistently recognizes the importance of leadership in mitigating burnout within this population of providers, this review identifies significant gaps in the literature and highlights opportunities for future research. The research recommendations offered in this review will, hopefully, expand the scope of burnout research, allowing scholars and organizational leaders to make more meaningful changes to address behavioral health provider burnout in research and practice.

Appendix

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality . Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamal R, Claxton G. Exploring mental and behavioral health and substance abuse. Kaiser Health System Tracker. 2016. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/exploring-mental-and-behavioral-health-and-substance-abuse/#item-start.

- 3.Alqashan HF, Alzubi A. Job satisfaction among counselors working at stress center—Social Development Office—in Kuwait. Traumatology: An International Journal. 2009;15(1):29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webster L, Hackett RK. Burnout and Leadership in Community Mental Health Systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 1999;26(6):387–399. doi: 10.1023/a:1021382806009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Workforce: Overview. https://www.samhsa.gov/workforce. 2017.

- 6.Paris M, Jr, Hoge MA. Burnout in the Mental Health Workforce: A Review. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2010;37(4):519–528. doi: 10.1007/s11414-009-9202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah JL, Kapoor R, Cole R, et al. Employee health in the mental health workplace: Clinical, administrative, and organizational perspectives. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2016;43(2):330–338. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior. 1981;2:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Low GS, Cravens DW, Grant K, et al. Antecedents and consequences of salesperson burnout. European Journal of Marketing. 2001;35(5/6):587–611. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lingard H. The impact of individual and job characteristics on 'burnout' among civil engineers in Australia and the implications for employee turnover. Construction Management and Economics. 2003;21(1):69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brenner JS. Overuse Injuries, Overtraining, and Burnout in Child and Adolescent Athletes. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):1242–1245. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fogarty T, Singh J, Rhoads G, et al.. Antecedents and Consequences of Burnout in Accounting: Beyond the Role Stress Model. 1997;Vol 12

- 14.Bowers L, Nijman H, Simpson A, et al. The relationship between leadership, teamworking, structure, burnout and attitude to patients on acute psychiatric wards. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46(2):143–148. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0180-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knudsen HK, Johnson JA, Roman PM. Retaining counseling staff at substance abuse treatment centers: effects of management practices. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahill S. Symptoms of professional burnout: A review of the empirical evidence. Canadian Psychology. 1988;29(3):284–297. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2012;39(5):341–352. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0352-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salyers MP, Flanagan ME, Firmin R, et al. Clinicians’ Perceptions of How Burnout Affects Their Work. Psychiatric Services. 2015;66(2):204–207. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salyers MP, Fukui S, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout and self-reported quality of care in community mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2015;42(1):61–69. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0544-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leiter MP, Maslach C. Six reas of worklife: A model of the organizational context of burnout. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration. 1999;21(4):472–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin U, Schinke SP. Organizational and individual factors influencing job satisfaction and burnout of mental health workers. Social Work in Health Care. 1998;28(2):51–62. doi: 10.1300/J010v28n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resources H, Administration S. National Projections of Supply and Demand for Behavioral Health Practitioners: 2013-2025. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration/Office of Policy, Planning, and Innovation: Rockville; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Network BHE. Addressing the Behavioral Health Workforce Shortage. Washington: National Council for Behavioral Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, et al. County-Level Estimates of Mental Health Professional Shortage in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(10):1323–1328. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrigan PW, Diwan S, Campion J, et al. Transformational leadership and the mental health team. Administration and policy in mental health. 2002;30(2):97–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1022569617123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanste O, Kyngäs H, Nikkil J. The relationship between multidimensional leadership and burnout among nursing staff. Journal of Nursing Management. 2007;15(7):731–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leiter MP, Harvie PL. Burnout among mental health workers: a review and a research agenda. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1996;42(2):90–101. doi: 10.1177/002076409604200203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sellgren S, Ekvall G, Tomson G. Nursing staff turnover: does leadership matter? Leadership in Health Services. 2007;20(3):169–183. doi: 10.1108/17511870710764023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Northouse PG. Leadership: Theory and Practice. 7. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bass BM, Bass R. The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications. 4. New York: Free Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabel S. Addressing demoralization in clinical staff: a true test of leadership. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2011;199(11):892–895. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182349e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabel S. Demoralization in mental health organizations: leadership and social support help. The Psychiatric Quarterly. 2012;83(4):489–496. doi: 10.1007/s11126-012-9217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onyett S. Revisiting job satisfaction and burnout in community mental health teams. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England) 2011;20(2):198–209. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.556170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, et al. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoff T, Carabetta S, Collinson GE. Satisfaction, Burnout, and Turnover Among Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Medical Care Research and Review : MCRR. 2019;76(1):3–31. doi: 10.1177/1077558717730157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giorgi G, Mancuso S, Fiz Perez F, et al. Bullying among nurses and its relationship with burnout and organizational climate. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2016;22(2):160–168. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee E, Esaki N, Kim J, et al. Organizational climate and burnout among home visitors: Testing mediating effects of empowerment. Children and Youth Services Review. 2013;35(4):594–602. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirk-Brown A, Wallace D. Predicting burnout and job satisfaction in workplace counselors: the influence of role stressors, job challenge, and organizational knowledge. Journal of Employment Counseling. 2004;41(1):29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stordeur S, D'Hoore W, Vandenberghe C. Leadership, organizational stress, and emotional exhaustion among hospital nursing staff. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;35(4):533–542. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heim E. Job Stressors and Coping in Health Professions. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1991;55(2-4):90–99. doi: 10.1159/000288414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prosser D, Johnson S, Kuipers E, et al. Mental health, ‘burnout’ and job satisfaction among hospital and community-based mental health staff. The British journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 1996;169(3):334–337. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziebland S, Wyke S. Health and illness in a connected world: how might sharing experiences on the internet affect people's health? Milbank Quarterly. 2012;90(2):219–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implementation Science. 2012;7(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leiter MP. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis; 1993. Burnout as a developmental process: Consideration of models; pp. 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leiter MP, Maslach C. Emotional and Physiological Processes and Positive Intervention Strategies. 2003. Areas of Worklife: A Structured Approach to Organizational Predictors of Job Burnout; pp. 91–134. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bass BM. From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics. 1990;18(3):19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spinelli RJ. The Applicability of Bass’s Model of Transformational, Transactional, and Laissez-Faire Leadership in the Hospital Administrative Environment. Hospital Topics. 2006;84(2):11–18. doi: 10.3200/HTPS.84.2.11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stone AG, Russell RF, Patterson K. Transformational versus servant leadership: a difference in leader focus. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 2004;25(4):349–361. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skogstad A, Einarsen S, Torsheim T, et al. The destructiveness of laissez-faire leadership behavior. Journal of occupational health psychology. 2007;12(1):80. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mowday RT, Sutton RI. Organizational Behavior: Linking Individuals and Groups to Organizational Contexts. Annual Review of Psychology. 1993;44(1):195–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.001211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cordes CL, Dougherty TL. A review and integration of research on job burnout. Academy of Management Review. 1993;18(4):621–656. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Family Medicine. 2005;37(5):360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bijari B, Abassi A. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome and Associated Factors Among Rural Health Workers (Behvarzes) in South Khorasan. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2016;18(10):e25390. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.25390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Broome KM, Knight DK, Edwards JR, et al. Leadership, burnout, and job satisfaction in outpatient drug-free treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37(2):160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aarons GA, Sommerfeld DH, Willging CE. The soft underbelly of system change: The role of leadership and organizational climate in turnover during statewide behavioral health reform. Psychological Services. 2011;8(4):269–281. doi: 10.1037/a002619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green AE, Miller EA, Aarons GA. Transformational leadership moderates the relationship between emotional exhaustion and turnover intention among community mental health providers. Community Mental Health Journal. 2013;49(4):373–379. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9463-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Green AE, Albanese BJ, Shapiro NM, et al. The roles of individual and organizational factors in burnout among community-based mental health service providers. Psychological Services. 2014;11(1):41–49. doi: 10.1037/a0035299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Madathil R, Heck NC, Schuldberg D. Burnout in Psychiatric Nursing: Examining the Interplay of Autonomy, Leadership Style, and Depressive Symptoms. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2014;28(3):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crawford MJ, Adedeji T, Price K, et al. Job satisfaction and burnout among staff working in community-based personality disorder services. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2010;56(2):196–206. doi: 10.1177/0020764009105702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yanchus NJ, Periard D, Osatuke K. Further examination of predictors of turnover intention among mental health professionals. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing. 2017;24(1):41–56. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holmberg R, Fridell M, Arnesson P, et al. Leadership and implementation of evidence-based practices. Leadership in Health Services. 2008;21(3):168–184. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakakis K, Ouzouni C. Factors influencing stress and job satisfaction of nurses working in psychiatric units: a research review. Health Science Journal. 2008;2(4):183–195. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rui S, Shilei Z, Hang X, et al. Regulatory focus and burnout in nurses: The mediating effect of perception of transformational leadership. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2015;21(6):858–867. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greenleaf RK. Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness, 25th anniversary Ed. Mahwah: Paulist Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schneider SK, George WM. Servant leadership versus transformational leadership in voluntary service organizations. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 2011;32(1):60–77. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoch JE, Bommer WH, Dulebohn JH, et al. Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management. 2018;44(2):501–529. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Upadyaya K, Vartiainen M, Salmela-Aro K. From job demands and resources to work engagement, burnout, life satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and occupational health. Burnout Research. 2016;3(4):101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Devers KJ. How will we know “good” qualitative research when we see it? Beginning the dialogue in health services research. Health Services Research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1153–1188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tariq S, Woodman J. Using mixed methods in health research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Short Reports. 2013;4(6):2042533313479197. doi: 10.1177/2042533313479197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weiner BJ, Amick HR, Lund JL, et al. Use of qualitative methods in published health services and management research: a 10-year review. Medical Care Research and Review. 2011;68(1):3–33. doi: 10.1177/1077558710372810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johns G. The Essential Impact of Context on Organizational Behavior. Academy of Management Review. 2006;31(2):386–408. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alexander JA, Hearld LR. Methods and metrics challenges of delivery-system research. Implementation Science. 2012;7(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Chandler J, et al. The role of evidence, context, and facilitation in an implementation trial: implications for the development of the PARIHS framework. Implementation Science. 2013;8(1):28. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Babcock-Roberson ME, Strickland OJ. The relationship between charismatic leadership, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Journal of Psychology. 2010;144(3):313–326. doi: 10.1080/00223981003648336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arnold KA. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2017;22(3):381–393. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Erwin DG, Garman AN. Resistance to organizational change: linking research and practice. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 2010;31(1):39–56. [Google Scholar]