Abstract

Objectives

Echocardiographic (echo) screening is an important tool to estimate rheumatic heart disease (RHD) prevalence, but the natural history of screen-detected RHD remains unclear. The PROVAR+ (Programa de RastreamentO da VAlvopatia Reumática) study, which uses non-experts, telemedicine and portable echo, pioneered RHD screening in Brazil. We aimed to assess the mid-term evolution of Brazilian schoolchildren (5–18 years) with echocardiography-detected subclinical RHD and to assess the performance of a simplified score consisting of five components of the World Heart Federation criteria, as a predictor of unfavourable echo outcomes.

Setting

Public schools of underserved areas and private schools in Minas Gerais, southeast Brazil.

Participants

A total of 197 patients (170 borderline and 27 definite RHD) with follow-up of 29±9 months were included. Median age was 14 (12–16) years, and 130 (66%) were woman. Only four patients in the definite group were regularly receiving penicillin.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Unfavourable outcome was based on the 2-year follow-up echo, defined as worsening diagnostic category, remaining with mild definite RHD or development/worsening of valve regurgitation/stenosis.

Results

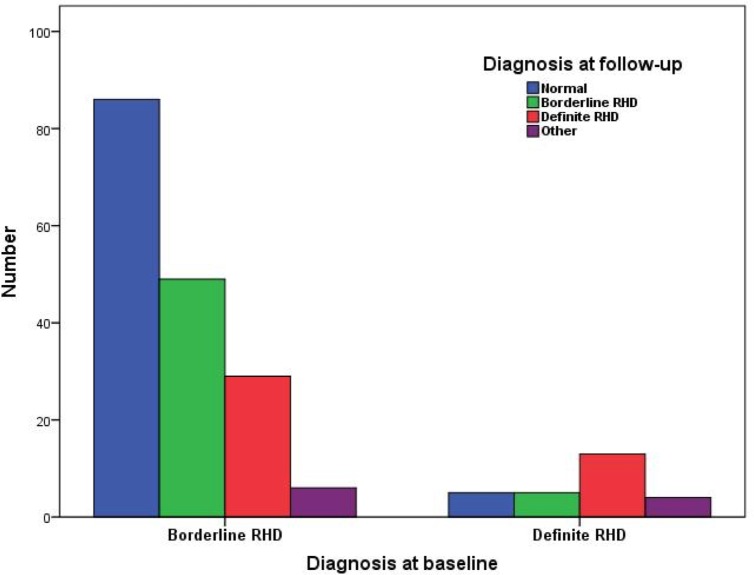

Among patients with borderline RHD, 29 (17.1%) progressed to definite, 49 (28.8%) remained stable, 86 (50.6%) regressed to normal and 6 (3.5%) were reclassified as other heart diseases. Among those with definite RHD, 13 (48.1%) remained in the category, while 5 (18.5%) regressed to borderline, 5 (18.5%) regressed to normal and 4 (14.8%) were reclassified as other heart diseases. The simplified echo score was a significant predictor of RHD unfavourable outcome (HR 1.197, 95% CI 1.098 to 1.305, p<0.001).

Conclusion

The simple risk score provided an accurate prediction of RHD status at 2-year follow-up, showing a good performance in Brazilian schoolchildren, with a potential value for risk stratification and monitoring of echocardiography-detected RHD.

Keywords: paediatric rheumatology, echocardiography, paediatric cardiology, ultrasound, cardiovascular imaging

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used the PROVAR+ (Programa de RastreamentO da VAlvopatia Reumática) cohort, the first large prospective cohort of schoolchildren with latent rheumatic heart disease (RHD) in Brazil.

This is the first validation study of a previously published (2019) scoring system to discriminate children found to have early echocardiography evidence of RHD into those who are likely to have favourable versus unfavourable outcomes.

Echocardiograms were interpreted by the consensus of two experts with high familiarity in the World Heart Federation criteria.

As this was an established cohort, no predefined sample size was calculated for this study and all screen-positive patients were invited for follow-up.

A passive recruitment strategy meant that there was low overall participation; only 36% of screen-positive children were enrolled in the follow-up programme, reducing the size of the potential cohort.

Introduction

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is the major cause of acquired cardiovascular disease in children and young adults worldwide. Its global burden is noteworthy, affecting 39 million people and causing 319 400 deaths annually.1 2 The disease is more prevalent in low-income and middle-income countries, where it is typically diagnosed only once advanced valve disease is present and symptoms develop.1 However, there is a latent period, often up to a decade, between the first episode of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and advanced RHD, when early identification can improve outcomes.

In this context, echocardiographic (echo) screening in endemic areas has emerged as an effective approach to identify patients who are in this latent, subclinical stage of RHD.3–6 Diagnostic criteria for subclinical RHD—asymptomatic patients with echo findings suggestive of RHD without a history of ARF—have been standardised by the World Heart Federation (WHF) consensus in 2012. Three categories are defined: definite, borderline and normal.7 The morphological findings of RHD and the criteria for pathologic valve regurgitation are also established. This standardisation has allowed for comparison between studies carried out in different populations.

Although criteria are standardised, prognosis and natural history of latent RHD, and the impact of clinical interventions—such as secondary prophylaxis—still require further evaluation. The first studies that evaluated the follow-up of patients with subclinical RHD have several limitations, including relatively short follow-up times, small sample size and lack of standardised criteria for echo and clinical progression.8 However, data suggest that RHD progression in children with latent RHD is not negligible.9 Therefore, we aimed to assess the mid-term evolution of Brazilian schoolchildren (5–18 years) with subclinical RHD findings observed in echo screening4 5 10 and to assess the performance of a simplified score developed by Nunes et al,9 consisting of five components of the WHF criteria, as a predictor of unfavourable echo outcomes.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study with systematic clinical and echo follow-up of children with subclinical RHD. It was derived from a RHD screening programme, stablished in Brazil in 2014—the PROVAR+ (Programa de RastreamentO da VAlvopatia Reumática) study—a collaboration between the Children’s National Health System, Washington, DC, USA, the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) and the Telehealth Network of Minas Gerais,11 Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. This screening programme has already screened more than 12 000 children and adolescents from 21 schools in Minas Gerais, Brazil, between October 2014 and December 2016.4 5 10

In brief, public schools and primary care centres from low-income areas of metropolitan Belo Horizonte, Brazil, were selected to participate in the screening programme, based on socioeconomic data (Human Development Index (HDI)) and priorities of the health authorities. Two selected private schools were also invited in order to characterise RHD in high-income youth. All asymptomatic students, without a history of ARF or RHD, were eligible for screening.4 5 All participants were informed about the study and had informed consent signed by their parents or by themselves, if of legal age.

The echo screening was performed from 2014 to 2016 by previously trained non-physicians (nurses and imaging technicians) and images were uploaded to a dedicated cloud storage system and interpreted through telemedicine by cardiologists in Brazil and the USA,12 applying the WHF criteria. Detailed screening methodology has been previously published.4 5

Participants with abnormal screening were invited for the UFMG Pediatric Cardiology outpatient clinics and were prospectively enrolled. All patients included in the follow-up from Belo Horizonte had the baseline screening diagnosis confirmed by standard echocardiography, scheduled in the University Hospital. The ones from Montes Claros had the diagnosis based on consensus reads of GE VSCAN handheld studies. Specific care of these patients was left to the discretion of the caring cardiologist with experience in RHD. Families received phone reminders of the follow-up visits and, when necessary, study correspondence by mail. The prespecified 24-month follow-up consisted of a clinical appointment by a paediatrician (BMB and ACD), with standardised clinical history (demographics, comorbidities, cardiovascular symptoms, recurrence of pharyngitis, medications and adherence to prophylaxis—when indicated) and detailed physical examination forms, and standard echocardiogram by an experienced paediatric cardiologist (SDR) (Vivid IQ, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA), blinded to the findings of the previous examination and based on the WHF criteria. A standardised imaging protocol was applied. Patients were then reclassified by consensus with adjudication by two experts (MCPN and ZMAM) in the four pre-established categories. Specific care of these patients and indication for secondary prophylaxis—not mandatory for any category—were left to the discretion of the caring cardiologist (ZMAM, SRTC and MCPN). All echo and clinical variables were systematically collected in a dedicated online database.

The simplified echo score proposed by Nunes et al, consisting of five variables (mitral valve anterior leaflet thickening, excessive leaflet tip motion, regurgitation jet length ≥2 cm and aortic valve focal thickening and any regurgitation)9 was applied to this population. An unfavourable outcome was defined as worsening in diagnostic category (borderline to definite), remaining with mild definite RHD or worsening in the grade of mitral or aortic valve regurgitation or development/worsening grade of mitral stenosis. A favourable outcome was defined as disease regression—considered when an improvement in diagnostic category was observed or in case of reduction of regurgitation severity—or remaining with stable borderline RHD.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design and conduct of this research.

Data analysis and statistics

Data were systematically entered into the RedCap online database.13 Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software V.23.0 for Mac OSX (SPSS). As we used a pre-existing cohort, no prespecified sample size calculation was performed, and we considered the total sample of asymptomatic schoolchildren enrolled in the 26-month screening. All screen-positive children who attended the follow-up visit were included in this analysis. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or as median and IQR, (Q1/Q3) when appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute values and percentages. The between-group comparison (progression vs regression/stable) was performed using the Fisher’s Exact Test for categorical variables.

The simplified echo score9 was applied to this population of schoolchildren to assess its discrimination and calibration in predicting unfavourable outcome using logistic regression. The predictive value of the score was assessed as a time-dependent variable in the Cox proportional hazards model. RHD favourable outcome rates of the three risk categories (low/intermediate/high), based on the hazard of evolving with unfavourable echo outcome, were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. A two-tailed significance level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 197 patients were included, being 114 (36%) out of 317 children with positive screening echos in Belo Horizonte and 83 (37%) of 224 in Montes Claros, with a mean 29±9 (range 11–48) months follow-up, considering the latest clinical visit. At baseline, 170 (86.3%) had borderline and 27 (13.7%) had definite RHD. Median age was 14.1 (IQR 12.0–16.2) years, and 130 (66%) were woman. Belo Horizonte and Montes Claros had similar rates of borderline (85.1% vs 88.0%) and definite (14.9% vs 12.0%) RHD at baseline (p=0.56). Only 13 (6.6%) patients, 4 of whom originally classified as definite RHD, were regularly receiving penicillin (7 with <80% adherence). Detailed baseline demographic and echo characteristics are depicted in table 1. Compared with the 344 patients without follow-up, the study sample had similar baseline distribution of borderline/definite diagnoses (86.3%/13.7% vs 89.5%/10.5%, p=0.26) as well as WHF subgroups for borderline (p=0.27) and definite (p=0.10) RHD, HDI (0.77 (IQR 0.76–0.80) vs 0.77 (IQR 0.76–0.80), p=0.22), household (4 (IQR 4–5) vs 4 (IQR 4–6) inhabitants, p=0.25) and age (14.2 (IQR 12.0–16.2) vs 14.1 (IQR 11.8–15.8) years, p=0.46), but a slightly higher proportion of women (66.3% vs 57.0%, p=0.03) was observed.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with borderline and definite rheumatic heart disease

| Variable | Result |

| Borderline RHD (N=170) | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 14 (11–16) |

| Female gender, N (%) | 111 (65.7) |

| Follow-up period (months), mean±SD | 28.9 ± 9.0 |

| At least two morphological features of RHD of the MV without pathological MR or MS | 5 (2.9) |

| Pathological MR | 135 (79.4) |

| Pathological AR | 30 (17.6) |

| Definite RHD (N=27) | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 14.0 (12–16) |

| Female gender, N (%) | 19 (70.4) |

| Follow-up period (months), mean±SD | 29.5±9.2 |

| Pathological MR and at least two morphological features of RHD of the MV | 24 (88.9) |

| MS mean gradient ≥4 mm Hg | 0 |

| Pathological AR and at least two morphological features of RHD of the AV | 0 |

| Borderline disease of both the AV and MV | 3 (11.1) |

AR, aortic regurgitation; AV, aortic valve; MR, mitral regurgitation; MS, mitral stenosis; MV, mitral valve; RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Cardiovascular symptoms were reported by 69 (35%) patients in the follow-up visits, including dyspnoea (15.2%) and palpitations (14.2%). However, clinical evaluation, physical examination and echocardiograms did not support a cardiac aetiology of these symptoms. During the follow-up, at least one episode of pharyngitis was reported by 92 patients, with 62 (67%) adequately treated in primary care, as informed by patients or parents.

Among patients with borderline RHD, 29 (17.1%) progressed to definite RHD, 49 (28.8%) remained stable, 86 (50.6%) regressed to normal and 6 (3.5%) were reclassified as other heart diseases. Among those with definite RHD, 13 (48.1%) remained in the category, while 5 (18.5%) regressed to borderline, 5 (18.5%) regressed to normal and 4 (14.8%) were reclassified as other heart diseases (figure 1). No patients had worsening grade of mitral or aortic regurgitation or development/worsening grade of mitral stenosis.

Figure 1.

RHD progression during the follow-up according to the diagnosis at baseline. RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Among borderline patients who progressed, 26 (89.7%) had mitral regurgitation, 2 had aortic regurgitation and 14 (48.3%) had at least one morphological abnormality of the mitral valve as the initial criteria. At follow-up, 12 patients developed morphological abnormalities of the mitral (N=10) and aortic (N=4) valves. No patients developed ventricular dysfunction or enlargement (table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline echocardiographic variables of patients with progression, stabilisation and regression of rheumatic heart disease at 2-year follow-up

| Valve | Variable* | Progressed: borderline to definite (N=29) | Remained definite (N=11) | Regressed/stable (borderline)/other (N=156) |

| Mitral valve, N (%) | Anterior leaflet thickening† | 18 (62.1) | 10 (90.9) | 103 (65.6) |

| Chordal thickening | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 0 | |

| Restricted leaflet motion | 1 (3.4) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Excessive leaflet tip motion | 2 (6.9) | 6 (54.5) | 20 (12.7) | |

| Mitral stenosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Any regurgitation | 28 (96.6) | 11 (100) | 141 (90.4) | |

| Regurgitation seen in two views | 26 (89.7) | 10 (90.9) | 141 (90.4) | |

| Jet length ≥2 cm‡ | 25 (86.2) | 9 (81.8) | 116 (74.4) | |

| Velocity ≥3 m/s for one envelope§ | 9 (31.0) | 4 (36.4) | 32 (20.5) | |

| Pansystolic jet (colour Doppler) | 15 (51.7) | 8 (72.7) | 99 (63.5) | |

| Aortic valve, N (%) | Irregular or focal thickening | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 1 (0.6) |

| Coaptation defect | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Restricted leaflet motion | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Leaflet prolapse | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Any regurgitation | 2 (6.9) | 3 (27.3) | 32 (20.5) | |

| Regurgitation seen in two views | 2 (6.9) | 2 (18.2) | 28 (17.9) | |

| Jet length ≥1 cm‡ | 1 (3.5) | 3 (27.3) | 29 (18.6) | |

| Velocity ≥3 m/s in early diastole§ | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 6 (3.9) | |

| Pandiastolic jet (colour Doppler) | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 20 (12.8) |

** Congenital mitral valve or aortic valve abnormalities were excluded.

† Abnormal thickening of the anterior mitral valve leaflet ≥3 or >4 mm using harmonic imaging.

‡ In at least 1 view.

§ Measurements available with the Vivid-Q exams.

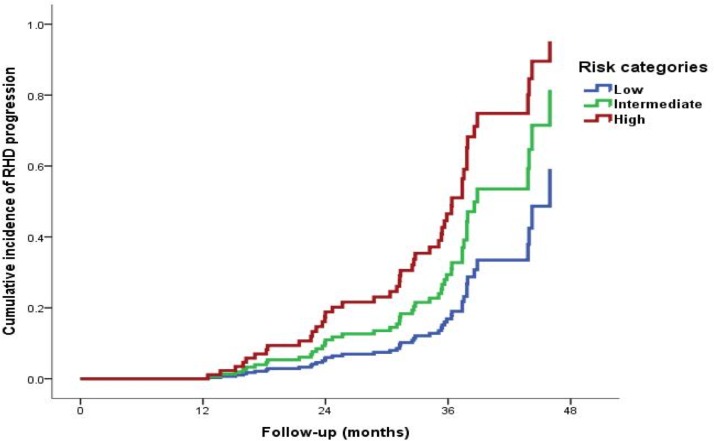

Predictive performance of the simplified echocardiographic score

The simplified score, based on components of the WHF criteria, was a significant predictor of RHD unfavourable outcome (HR 1.197, 95% CI 1.098 to 1.305, p<0.001). The discrimination of the score was good (C-statistic=0.714, 95% CI 0.627 to 0.801), and the model was well calibrated (online supplementary appendix figure 1). A Hosmer-Lemeshow p=0.589 confirmed no significant difference between observed and predicted unfavourable outcome (online supplementary appendix figure 2A, B).

bmjopen-2020-036827supp001.pdf (998.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-036827supp002.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)

The score classified 121 children in low-risk, 48 in the intermediate-risk and 28 in the high-risk groups. Additionally, the score model was able to separate low-risk, intermediate-risk and high-risk categories for unfavourable disease outcomes (figure 2). Favourable RHD outcome risk rate in the low-risk children at 1-year and 2-year follow-up was 99% and 97%, respectively, compared with 76% and 47% in the high-risk group.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of disease unfavourable outcomes in children with echocardiography-detected RHD according to risk categories of the simplified score. RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Discussion

In agreement with the growing international data,8 subclinical RHD in Brazil has a variable outcome. Approximately one in five children with borderline RHD progressed to definite RHD and more than one in three children with definite RHD remained in this category. A recently developed risk stratification score9 was a modest, but significant, predictor of unfavourable echo outcome in our population.

Since its inception, the PROVAR+ research programme has been studying the use of echocardiography to improve the early detection of RHD12 in Brazil. Epidemiological characterisation of RHD prevalence, and study of portable and handheld devices, task-shifting and telemedicine have been undertaken to understand how to improve diagnostic access in low-resource populations.4 10 12 14 Determining outcomes for children with subclinical RHD is a critical next step to inform programme evaluation, as for other screening programmes worldwide. These data, with a mean follow-up of 29 months, show that both borderline and definite RHD are dynamic phenotypes, with borderline RHD showing more favourable outcomes.6 8 15

Nearly half (46%) of the youth in this programme improved echocardiographically to normal, similar to global rates ranging from 47% to 67%.8 16 Yet borderline RHD was not a benign finding, with one in five (17%) of children progressing to definite RHD, in line with global data, which have reported 17%–23% progression at 2.5–7.5 years of follow-up.8 17 18 Children with definite RHD at diagnosis had more unfavourable outcomes with 40% remaining definite, though no child progressed to moderate or severe RHD, reflecting a mildly phenotype in screen-detected RHD in Brazilian youth compared with the global data.8 15 17 19 20 This milder phenotype may reflect the relatively stronger public health system in Brazil, compared with many other RHD-endemic areas, facilitating higher rates of sore throat and rheumatic fever diagnoses, but more data are needed. The impact of secondary prophylaxis in this cohort cannot be determined, as few were prescribed prophylaxis and adherence was not well captured, and we await the results of a large randomised clinical trial on the impact of penicillin prophylaxis in screen-detected youth, currently ongoing in Uganda (Gwoko Adunu pa Lutino (GOAL); clinicaltrials.gov No. NCT03346525).

The most novel aspect of this follow-up study was the application of a newly developed score to predict unfavourable outcome among children with screen-detected RHD.9 Addressing the need to simplify the WHF criteria and improve the applicability for use with handheld echocardiography (lacking spectral Doppler), Nunes et al developed a five-component point-based score that showed considerable accuracy for predicting disease progression in two large African cohorts.9 The score showed modest discrimination for unfavourable outcome in our population, potentially related to the less aggressive RHD phenotype in Brazil as compared with African cohorts,8 19 suggesting wider external validation and recalibration may be necessary for global application. However, still in a population with a relatively low risk of progression—especially to clinically significant disease—its discrimination of subgroups at higher risk of unfavourable echo outcome points towards a useful public health tool and urges further investigations.

The PROVAR+ programme has encountered several context-specific limitations and lessons learnt. First, the programme has struggled with low-participation and high attrition compared with other global populations: only 40% of students have consented to school-based screening5 and only 36% of screen-positive children from the schools were enrolled in follow-up. Consequently, the sample size was limited—although comparable with other RHD follow-up studies—and may preclude more definite conclusions. Much higher participation rates were seen in primary healthcare screening (84.4%,5 suggesting this location is more appropriate in our context. Second, in the absence of a gold standard, prescription of penicillin for secondary prophylaxis was left to the discretion of the treating physician. Low rates of prescription were seen compared with those reported globally, suggesting the need for widespread provider education based on the results from the GOAL (Gwoko Adunu pa Lutino; clinicaltrials.gov No. NCT03346525) study. Finally, no child progressed to clinically significant RHD, suggesting the timeline of progression may be longer in the Brazilian context and not adequately captured by the relatively short follow-up interval. This may have important implications on when to screen and cost-effectiveness evaluations. Despite these limitations, the PROVAR+ programme is the only longitudinal programme evaluating the impact of echoscreening in Latin America.

Conclusion

These data suggest that screen-detected RHD in Brazil is not benign; patients with definite RHD are likely to remain in this category, and progression rates of borderline RHD are not negligible. The simplified echocardiography score9 assessed in an independent population with predominantly low risk for RHD progression was accurate to predict early unfavourable outcome. Additional investigations are needed to establish the long-term prognosis of subclinical RHD and the effects of prophylaxis in high-risk subgroups.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @ramosnas

Collaborators: On behalf of all the PROVAR (Programa de RastreamentO da VAlvopatia Reumática) investigators

Contributors: Conception and design of the research: BMB, BRN, CS, AZB, MCPN, ALPR; Acquisition of data: BMB, CLF, MMB, SDR, ZMAM, SRTC, NFA, KKO, ACD, BDFR, WAAC, MDM and AFP. Analysis and interpretation of data: BRN, MCPN, CS, AZB, SDR, ZMAM, SRTC and NFA. Statistical analysis: JLPS, BRN, ALPR and CS. Obtaining financing: AZB, CS and BRN. Writing of the manuscript: BMB, BRN, CS and MCPN. Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: all authors. Authors responsible for the overall content as guarantors: BMB, BRN, AZB, ALPR, CS and MCPN.

Funding: This study was funded by Edwards Lifesciences Foundation, USA. The PROVAR+ investigators would like to thank Edwards Lifesciences Foundation for supporting and funding the primary care screening program (PROVAR+) in Brazil, General Electric Healthcare for providing echocardiography equipment and WiRed Health Resources for providing online curriculum on heart disease and echocardiography. The Telehealth Network of Minas Gerais was funded by the State Government of Minas Gerais, by its Health Department (Secretaria de Estado da Saúde de Minas Gerais) and FAPEMIG (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa de Minas Gerais), and by the Brazilian Government, including the Health Ministry and the Science and Technology Ministry and its research and innovation agencies, CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) e FINEP (Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos). Dr Ribeiro was supported in part by CNPq (Bolsa de produtividade em pesquisa, 310679/2016-8) and by FAPEMIG (Programa Pesquisador Mineiro, PPM-00428-17). Medical students received scholarships from the National Institute of Science and Technology for Health Technology Assessment (IATS, project: 465518/2014-1).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, and ethics approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of the participant institutions (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais and Children’s National Health System Institutional Review Board) as well as from the local Boards of Health and Education.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Data analytic methods and study materials will be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure, from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med 2017;377:713–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1789–858. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamantino A, Beaton A, Aliku T, et al. A focussed single-view hand-held echocardiography protocol for the detection of rheumatic heart disease. Cardiol Young 2018;28:108–17. 10.1017/S1047951117001676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nascimento BR, Beaton AZ, Nunes MCP, et al. Echocardiographic prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in Brazilian schoolchildren: data from the PROVAR study. Int J Cardiol 2016;219:439–45. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nascimento BR, Sable C, Nunes MCP, et al. Comparison between different strategies of rheumatic heart disease echocardiographic screening in Brazil: data from the PROVAR (rheumatic valve disease screening program) study. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7. 10.1161/JAHA.117.008039. [Epub ahead of print: 14 Feb 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaton A, Aliku T, Okello E, et al. The utility of handheld echocardiography for early diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2014;27:42–9. 10.1016/j.echo.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease--an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:297–309. 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zühlke L, Engel ME, Lemmer CE, et al. The natural history of latent rheumatic heart disease in a 5 year follow-up study: a prospective observational study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2016;16:1–6. 10.1186/s12872-016-0225-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunes MCP, Sable C, Nascimento BR, et al. Simplified echocardiography screening criteria for diagnosing and predicting progression of latent rheumatic heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12:e007928. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.007928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos JPAD, Carmo GALdo, Beaton AZ, et al. Challenges for the implementation of the first large-scale rheumatic heart disease screening program in Brazil: the PROVAR study experience. Arq Bras Cardiol 2017;108:370–4. 10.5935/abc.20170047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alkmim MB, Figueira RM, Marcolino MS, et al. Improving patient access to specialized health care: the telehealth network of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:373–8. 10.2471/BLT.11.099408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopes EL, Beaton AZ, Nascimento BR, et al. Telehealth solutions to enable global collaboration in rheumatic heart disease screening. J Telemed Telecare 2018;24:101–9. 10.1177/1357633X16677902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaton A, Nascimento BR, Diamantino AC, et al. Efficacy of a standardized computer-based training curriculum to teach echocardiographic identification of rheumatic heart disease to Nonexpert users. Am J Cardiol 2016;117:1783–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotit S, Said K, ElFaramawy A, et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of echocardiographic screening for rheumatic heart disease. Open Heart 2017;4:e000702. 10.1136/openhrt-2017-000702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaton A, Aliku T, Dewyer A, et al. Latent rheumatic heart disease: identifying the children at highest risk of unfavorable outcome. Circulation 2017;136:2233–44. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelman D, Wheaton GR, Mataika RL, et al. Screening-Detected rheumatic heart disease can progress to severe disease. Heart Asia 2016;8:67–73. 10.1136/heartasia-2016-010847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rémond M, Atkinson D, White A, et al. Are minor echocardiographic changes associated with an increased risk of acute rheumatic fever or progression to rheumatic heart disease? Int J Cardiol 2015;198:117–22. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beaton A, Okello E, Aliku T, et al. Latent rheumatic heart disease: outcomes 2 years after echocardiographic detection. Pediatr Cardiol 2014;35:1259–67. 10.1007/s00246-014-0925-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanyahumbi A, Beaton A, Guffey D, et al. Two-Year evolution of latent rheumatic heart disease in Malawi. Congenit Heart Dis 2019;14:614–8. 10.1111/chd.12756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-036827supp001.pdf (998.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-036827supp002.pdf (1.2MB, pdf)