Abstract

Objective

Symptoms and clinical course during inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) vary among individuals. Personalised care is therefore essential to effective management, delivered by a strong patient-centred multidisciplinary team, working within a well-designed service. This study aimed to fully rewrite the UK Standards for the healthcare of adults and children with IBD, and to develop an IBD Service Benchmarking Tool to support current and future personalised care models.

Design

Led by IBD UK, a national multidisciplinary alliance of patients and nominated representatives from all major stakeholders in IBD care, Standards requirements were defined by survey data collated from 689 patients and 151 healthcare professionals. Standards were drafted and refined over three rounds of modified electronic-Delphi.

Results

Consensus was achieved for 59 Standards covering seven clinical domains; (1) design and delivery of the multidisciplinary IBD service; (2) prediagnostic referral pathways, protocols and timeframes; (3) holistic care of the newly diagnosed patient; (4) flare management to support patient empowerment, self-management and access to specialists where required; (5) surgery including appropriate expertise, preoperative information, psychological support and postoperative care; (6) inpatient medical care delivery (7) and ongoing long-term care in the outpatient department and primary care setting including shared care. Using these patient-centred Standards and informed by the IBD Quality Improvement Project (IBDQIP), this paper presents a national benchmarking framework.

Conclusions

The Standards and Benchmarking Tool provide a framework for healthcare providers and patients to rate the quality of their service. This will recognise excellent care, and promote quality improvement, audit and service development in IBD.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, IBD, colitis, ulcerative colitis, UC, Crohn’s disease, CD, guideline, standards, quality improvement, multidisciplinary team, MDT, audit, cost-effectiveness, service development, pathway, protocol, patient education, self-management, benchmark, paediatrics, gastroenterology

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic relapsing remitting condition that affects 500 000 people or more in the UK. The clinical features, symptoms and impact of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis on the patient are highly variable and complex and may change over time.

The 2009 and 2013 UK IBD Standards were developed to support service design, development and quality improvement in light of UK-wide audit data highlighting significant variations in the standards of IBD care. While this has led to demonstrable improvements in care provision, audit data from 2014 demonstrated continued inequalities.

This has highlighted the need for multidisciplinary and patient-centred service design and care provision in order to provide personalised care, in particular, access to specialist assessment at referral and relapse; appropriate provision for IBD nurse specialists, dietetic and psychological support; patient education opportunities and involvement of patients in service planning.

Significance of this study.

What does this study add?

Led by IBD UK, a multidisciplinary and patient representative working group, this study represents an entire rewrite of the UK IBD Standards.

Underpinned by extensive qualitative survey response from patients and healthcare professionals, three rounds of modified e-Delphi have produced 59 consensus Standards grouped around the patient journey covering service setup, multidisciplinary delivery, patient information, empowerment, shared care and self-management.

Informed by the new Standards and the IBD Quality Improvement Project, a service Benchmarking Tool has been developed, allowing healthcare professionals and, for the first time, patients the ability to rate, compare and benchmark the quality of IBD care provided across the UK.

How might this study impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

The IBD Standards and online Benchmarking Tool provide a strong patient-centred framework for ongoing service development and quality improvement in UK-wide IBD care. Through enhanced partnership between patients and healthcare professionals, this tool has the potential to address inequalities in healthcare provision, to enhance shared decision-making and to promote the development of personalised care models

Introduction

Over 500 000 people in the UK are estimated to be affected by inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1 2 As lifelong, relapsing and complex conditions, medical costs associated with the care of the principal forms of IBD (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) can be comparable with those for major chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and cancer. The estimated average cost of treating a patient with ulcerative colitis is £3084 per year and that of treating a patient with Crohn’s disease is £6156 per year.3 While surgery rates appear to be decreasing for Crohn’s disease,4 any associated reduction in NHS costs may be offset by increased use of biological therapies.5

The first UK Service Standards for the healthcare of people who have IBD6 were developed by patient and professional associations and were published in 2009 in response to a UK-wide audit highlighting significant variation in care.7 The IBD Standards defined what was required in terms of staff, support services, organisation, patient education and audit to provide integrated, high-quality IBD services. The 2013 updated IBD Standards8 underpinned the 2015 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standard on IBD (QS81)9 and were an integral component of the IBD Quality Improvement Programme in the UK10 supported by the Royal College of Physicians until 2015.

The fourth and final round of the UK IBD Audit in 2014 has demonstrated improvements in several areas of service provision, including increased numbers of IBD nurse specialists and dietitians and reduced mortality.11 12 However, it has also shown continuing variation in the quality and responsiveness of healthcare for people with IBD in the UK. Considerable issues have been highlighted in a number of areas, in particular, speed of access to specialist assessment at referral and relapse; appropriate provision for IBD nurse specialists, dietetic access and psychological support; patient education opportunities and involvement of patients in service planning. Previous rounds of audit have also shown a need for improved communication between primary care and secondary care.13

Recent work in the UK by Crohn’s & Colitis UK has shown that factors such as loneliness, degree of control and involvement in care are significantly associated with active disease, a reduction in quality of life and low life satisfaction.14 The considerable psychosocial impact of IBD on education, careers, social and intimate well-being is well-documented in quality of life studies.15 16 Furthermore, patient surveys have drawn attention to concerns around delays in diagnosis, timeliness of review and treatment, access to appropriate inpatient facilities, coordination and continuity of care.17 The surveys also highlight needs relating to patients’ understanding about their condition, available treatment options and involvement in shared decision-making.

The individual impact of IBD and experience of IBD services, together with an increasing focus on personalised care in the NHS6 across the UK, underlines the need for quality improvement methodologies in IBD. Future service design and development must be patient-centred and must include mechanisms to capture service outcomes that enable patients to monitor impact and shape solutions in the delivery of IBD services. The National Cancer Patient Experience Survey 2017 demonstrated significant improvement on 21/52 questions compared with the previous year’s results,18 highlighting the potential benefit of this type of approach if used to shape future UK IBD care.

Therefore, a complete revision of the UK IBD Standards was considered essential. This is particularly important due to the significant changes in IBD management since 2013, such as the complex range of new medical therapy options, the growing use of minimally invasive surgical techniques in the UK; the increased use, the general acceptance and use of new web-based communication technology; and recognition of the central importance of involving the patient in decision-making.

Methods

The IBD Standards 2019 methodology was designed to align with the 2019 British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) IBD guidelines19 and the 2018 Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI) IBD surgical guidelines.20 In addition, the process considered other relevant professional and NICE guidelines.

IBD UK and national stakeholders

The Standards development process was led from its inception by IBD UK, a national multidisciplinary alliance of nominated representatives from patient and professional organisations, with integrated patient involvement on the Standards Development Group and at all stages of the development process. Representation from all devolved nations ensured standards were applicable throughout the UK. The following organisations/stakeholders were represented by IBD UK (author affiliations or membership are denoted by initials):

Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland: AA, SJB, AD, JD and OF

British Association for Parental and Enteral Nutrition: NB

British Dietetic Association: AB and KK

British Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology: GB and SAT

British Society of Gastroenterology: IDA, ABH, CAL and AM

British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition: JE and RM

CICRA: NP

Crohn’s & Colitis UK: GB, JG and RK

UK IBD Registry: SB and FC

Ileostomy & Internal Pouch Association: AD

Primary Care Society for Gastroenterology: CA and KJB

Royal College of General Practitioners: KJB

Royal College of Nursing: KC, VG and LY

Royal College of Pathologists: RMF

Royal College of Physicians: IDA, ABH, CAL and SW

Royal Pharmaceutical Society: AStCJ

UK Clinical Pharmacy Association: AStCJ and UM

Online healthcare professional and patient surveys

The use and impact of previous iterations of the IBD Standards on healthcare professionals was assessed by an anonymous online survey to guide development of the Standards revision. An online survey of patients with IBD was also conducted. The Standards Development Group also reviewed the 2013 IBD Standards to formally identify where recommendations for service design and delivery should be updated or reinforced in light of evolving evidence-based clinical practice, patient perception and expert opinion.

IBD Standards consensus development and e-Delphi

Informed by the above patient and healthcare professional surveys and critical review of prior Standards iterations, the Standards Development Group then drafted statements. A reference group of 17 patients/carers from throughout the UK, who had previous experience of activity related to IBD service improvement, gave feedback on the Standards working document. The IBD Standards were then refined across three rounds of anonymised modified e-Delphi voting, developing recommendations for optimal service design and delivery and in relation to quality improvement or key performance measures; 28 voters assessed each statement on a 5-point scale (strongly agree (SA), agree (A), neither agree nor disagree (N), disagree (D) or strongly disagree (SD)). After each round of voting, the Standards were assessed and, if necessary, redrafted based on voter feedback. Agreement was defined as a score of ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’. Consensus agreement was defined as >80% agreement from the group. e-Delphi voters represented patients and all professional groups, including specialist nurses, gastroenterologists, colorectal surgeons, paediatricians, general practitioners (GPs), radiologists, pathologists, dietitians and pharmacists. Voters were geographically representative of the UK.

Development of the IBD Benchmarking Tool

Led by IBD UK, a Benchmarking Development Group identified the core components of service delivery, based on established good practice and/or multidisciplinary expert consensus at grading levels A–D to cover the range of IBD Standards statements. The service self-assessment tool was tested in a range of services and refined based on feedback. Development of the patient survey was led by Crohn’s & Colitis UK for IBD UK, with questions mapped to the IBD Standards statements and graded A–D in line with the service self-assessment tool. Initial questions were refined following feedback from a reference group of patients and parents/carers and were further cognitively tested through a focus group and telephone interviews.

Results

Online patient and health professional surveys

An online survey of 151 healthcare professionals (65 IBD nurse specialists, 60 gastroenterologists, 5 colorectal surgeons, 6 specialist pharmacists, 7 dietitians, 4 GPs, 2 nurse endoscopists, 1 radiologist and one trainee physiologist) assessed the usage and impact of previous iterations of the IBD Standards. 79.7% (n=122) reported that the document helped them to plan and develop their local service, 71.9% (n=110) said they helped to understand what a ‘great’ service should look like, and 81.7% (n=125) said the Standards had helped with business case development for new resources. A range of practical examples of the use of previous versions of the IBD Standards and suggestions for inclusion in this iteration of the Standards were cited by respondents. A thematic summary of these responses is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Thematic feedback from healthcare professionals and patients regarding use of previous IBD Standards and areas for inclusion for 2019 IBD Standards

| Healthcare professional survey (n=151) | Patient survey (n=689) |

Practical examples of use of IBD Standards in clinical practice

|

Suggestions for inclusion in 2019 IBD Standards

|

Suggestions for 2019 IBD Standards

|

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; QI, quality improvement; RCP, Royal College of Physicians.

An online survey carried out by IBD UK of 689 patients (45% Crohn’s disease, 40% ulcerative colitis, 3.3% IBDU, 0.7% microscopic colitis and 2% “other”) was assessed to determine patient preference for content of the IBD Standards and what would make the greatest impact on patient care. Thematic conclusions from this survey are summarised in table 1.

IBD Service Standards

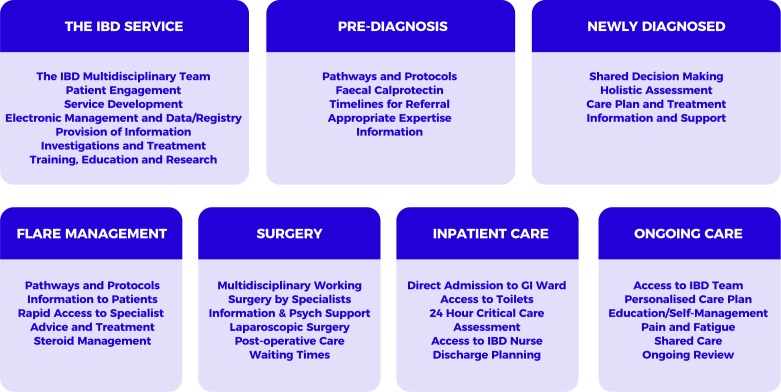

The 2019 IBD Standards were created to reflect the central position and importance of the patient in service design and delivery. In particular, a strengthened focus on surgery, primary care, paediatrics and patient empowerment was identified relative to previous iterations of the Standards. Accompanying tools and resources and a benchmarking process to support implementation were also advocated. The Standards development process therefore set out to follow the patient journey across seven sections from referral, through diagnosis, surgical and medical treatment, to long-term management of IBD (figure 1). The consensus IBD Standards following three rounds of modified e-Delphi are presented in boxes 1–7 according to each of the seven sections.

Figure 1.

2019 IBD Standards sections: seven sections following the patient journey from referral through to ongoing long-term care. Key considerations for optimal service design and delivery are shown grouped according to these sections. GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Box 1. The IBD service.

Statement 1.1: Patients should be cared for by a defined IBD multidisciplinary team led by a named consultant adult or paediatric gastroenterologist (consensus 96%: SA 71%, A 25%, N 4%).

Statement 1.2: Multidisciplinary team meetings should take place regularly to discuss appropriate patients (consensus 100%: SA 89%, A 11%).

Statement 1.3: Protocols should be in place, is which clearly define the local transition service and the personnel responsible (consensus 100%: SA 64%, A 36%).

Statement 1.4: The IBD service should have a leadership team that includes a senior clinician, an IBD nurse specialist and a manager who has responsibility for managing, monitoring and developing the service (consensus 100%: SA 61%, A 39%).

Statement 1.5: The IBD leadership team should work with an expert pharmacist in IBD to ensure good medicines governance, including medicine optimisation and cost-effectiveness (consensus 100%: SA 57%, A 43%).

Statement 1.6: IBD teams should promote continuous quality improvement and participate in local and national audit (consensus 100%: SA 68%, A 32%).

Statement 1.7: Patients and parents/carers should have a voice and direct involvement in the development of the service (consensus 100%: SA 64%, A 36%).

Statement 1.8: All patients with confirmed IBD should be recorded in an electronic clinical management system and data provided to the national IBD Registry (consensus 89%: SA 46%, A 43%, N 11%).

Statement 1.9: Clear information about IBD, the local IBD service and patient organisations should be accessible in outpatient clinics, wards, endoscopy and day care areas (consensus 96%: SA 57%, A 39%, SD 4%).

Statement 1.10: Endoscopic assessment and ultrasound/MRI/CT/contrast studies should be accessible within 4 weeks, and within 24 hours where patients are acutely unwell or require admission to the hospital (consensus 100%: SA 50%, A 50%).

Statement 1.11: Histological processing and reporting should take place routinely within five working days or within two working days for reporting of urgent biopsy samples (consensus 100%: SA 61%, A 39%).

Statement 1.12: Agreed protocols should be in place for pre-treatment tests, vaccinations, prescribing, administration and monitoring of immunomodulator and biological therapies (consensus 100%: SA 64%, A 36%).

Statement 1.13: Patients should be fully informed about the benefits and risks of, and the alternatives to, immunomodulator and biological therapies, including surgery (consensus 100%: SA 82%, A 18%).

Statement 1.14: Patients receiving immunomodulator and biological therapies should be offered vaccinations in accordance with clinical guidelines (consensus 100%: SA 57%, A 43%).

Statement 1.15: All forms of nutritional therapy should be available to patients with IBD, where appropriate, including exclusive enteral nutrition for Crohn’s disease and referral to services specialising in parenteral nutrition (consensus 100%: SA 71%, A 29%).

Statement 1.16: All members of the IBD team should develop competencies and be educated to a level appropriate for their role, with access to professional support and supervision (consensus 96%: SA 68%, A 28%, N 4%).

Statement 1.17: IBD services should encourage and facilitate involvement in multidisciplinary research through national or international IBD research projects and registries (consensus 100%: SA 50%, A 50%).

A, agree; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; N, neither agree nor disagree; SA, strongly agree; SD, strongly disagree.

Box 2. Pre-diagnosis.

Statement 2.1: Clear pathways and protocols for investigating children and adults with persistent lower gastrointestinal symptoms should be agreed between primary care and secondary care, and should include guidance on the use of faecal biomarker tests in primary care to aid rapid diagnosis (consensus 96%: SA 57%, A 39%, N 4%).

Statement 2.2: Patients who are referred with suspected IBD should be seen within 4 weeks, or more rapidly if clinically necessary (consensus 100%: SA 57%, A 43%).

Statement 2.3: Patients presenting with acute severe colitis should be admitted to a centre with medical and surgical expertise in managing IBD that is available at all times (consensus 100%: SA 68%, A 32%).

Statement 2.4: All patients should be provided with a point of contact and clear information about pathways and timescales while awaiting the outcome of tests and investigations (consensus 100%: SA 64%, A 36%).

A, agree; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; N, neither agree nor disagree; SA, strongly agree.

Box 3. Newly diagnosed.

Statement 3.1: All newly diagnosed patients with IBD should be seen by an IBD specialist and enabled to see an adult or paediatric gastroenterologist, IBD nurse specialist, specialist gastroenterology dietitian, surgeon, psychologist and expert pharmacist in IBD as necessary (consensus 100%: SA 75%, A 25%).

Statement 3.2: After diagnosis, all patients should have full assessment of their disease, nutritional status, bone health and mental health, with baseline infection screen, in order to develop a personalised care plan (consensus 100%: SA 43%, A 57%).

Statement 3.3: Patients should be supported to make informed, shared decisions about their treatment and care to ensure these take their preferences and goals fully into account (consensus 100%: SA 68%, A 32%).

Statement 3.4: After diagnosis, all outpatients with IBD should be able to start a treatment plan within 48 hours for moderate to severe symptoms and within 2 weeks for mild symptoms (consensus 100%: SA 54%, A 46%).

Statement 3.5: Patients should be signposted to information and support from patient organisations (consensus 100%: SA 70%, A 30%).

Statement 3.6: General practitioners should be informed of new diagnoses and the care plan that has been agreed within 48 hours (consensus 100%: SA 43%, A 57%).

A, agree; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SA, strongly agree.

Box 4. Flare management.

Statement 4.1: Local treatment protocols and clear pathways should be in place for the management of patients with IBD experiencing flares and should include advice for primary care (consensus 96%: SA 71%, A 25%, N 4%).

Statement 4.2: All patients with IBD should be provided with clear information to support self-management and early intervention in the case of a flare (consensus 100%: SA 64%, A 36%).

Statement 4.3: Rapid access to specialist advice should be available to patients to guide early flare intervention, including access to a telephone/email advice line with response by the end of the next working day (consensus 100%: SA 79%, A 21%).

Statement 4.4: Patients with IBD should have access to review by the IBD team within a maximum of five working days and should be able to escalate/start a treatment plan within 48 hours of review (consensus 100%: SA 61%, 39%).

Statement 4.5: Steroid treatment should be managed in accordance with guidelines and audited on an ongoing basis, with clear guidance to primary care (consensus 100%: SA 68%, A 32%).

A, agree; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; N, neither agree nor disagree; SA, strongly agree.

Box 5. Surgery.

Statement 5.1: Patients should have access to coordinated surgical and medical clinical expertise, including regular combined or parallel clinics with a specialist colorectal surgeon (paediatric colorectal surgeon where appropriate) and IBD gastroenterologist (consensus 100%: SA 64%, A 36%).

Statement 5.2: Elective IBD surgery should be performed by a recognised colorectal surgeon (paediatric colorectal surgeon where appropriate) who is a core member of the IBD team in a unit where such operations are undertaken regularly (consensus 96%: SA 75%, A 21%, D 4%).

Statement 5.3: In the absence of relevant local expertise, paediatric patients or adult patients requiring complex surgery should be referred to a specialist unit (consensus 100%: SA 71%, A 29%).

Statement 5.4: Patients with IBD being considered for surgery should be provided with information in a format and language they can easily understand to support shared decision-making and informed consent and should be offered psychological support (consensus 100%: SA 75%, A 25%).

Statement 5.5: Prior to elective surgery, a full assessment and optimisation of medical treatment and physical condition should be undertaken to minimise risk of complications and aid postoperative recovery (consensus 100%: SA 75%, A 25%).

Statement 5.6: Patients should be counselled about laparoscopic resection as an option, when appropriate, in accordance with clinical guidelines (consensus 100%: SA 71%, A 29%).

Statement 5.7: Patients and parents/carers should be provided with information about postoperative care before discharge, including wound and stoma care, and offered psychological support (consensus 100%: SA 64%, A 36%).

Statement 5.8: Elective surgery for IBD should be performed as soon as the patient’s clinical status has been optimised and within 18 weeks of referral for surgery (consensus 96%: SA 57%, A 39%, SD 4%).

A, agree; D, disagree; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SA, strongly agree; SD, strongly disagree.

Box 6. Inpatient care.

Statement 6.1: Patients requiring inpatient care relating to their IBD should be admitted directly, or transferred within 24–48 hours, to a designated specialist ward area under the care of a consultant gastroenterologist and/or colorectal surgeon (consensus 97%: SA 61%, A 36%, D 3%).

Statement 6.2: Where ensuite rooms are not available, inpatients with IBD should have a minimum of one easily accessible toilet per three beds on a ward (consensus 97%: SA 61%, A 36%, N 3%).

Statement 6.3: Inpatients with IBD must have 24-hour rapid access to critical care services if needed (consensus 97%: SA 79%, 18%, N 3%).

Statement 6.4: Children and adults admitted as inpatients with acute severe colitis should have daily review by appropriate specialists (consensus 96%: SA 75%, A 21%, N 4%).

Statement 6.5: For patients with acute severe colitis, stool culture and Clostridium difficile assay should be performed on admission to exclude infectious causes of colitis (consensus 100%: SA 71%, A 29%).

Statement 6.6: For patients admitted with acute severe colitis, limited flexible sigmoidoscopy, when indicated, should be performed without bowel preparation by an experienced endoscopist (consensus 100%: SA 64%, A 36%).

Statement 6.7: All patients with acute severe colitis not settling on intravenous steroids should be assessed regularly by a consultant adult/paediatric colorectal surgeon and a decision made with the patient and adult/paediatric gastroenterologist on day three to escalate to rescue therapy or undertake a colectomy (Consensus 93%: SA 61%, A 32%, N 4%, D 3%).

Statement 6.8: On admission, patients with IBD should have an assessment of nutritional status, mental health and pain management using validated tools, and should be referred to services and support as appropriate (consensus 100%: SA 50%, A 50%).

Statement 6.9: All inptients with IBD should have access to an IBD nurse specialist (consensus 100%: SA 71%, A 29%).

Statement 6.10: All inpatients with IBD should have their prescribed and over the counter medications reviewed on admission by a pharmacist who has access to an expert pharmacist in IBD for advice, with regular review of medications during their inpatient stay and at discharge (consensus 100%: SA 46%, A 54%).

Statement 6.11: Clear written information about follow-up care and prescribed medications should be provided before discharge from the ward and communicated to the patient’s IBD clinical team and GP within 48 hours of discharge (consensus 100%: SA 57%, A 43%).

A, agree; D, disagree; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; N, neither agree nor disagree; SA, strongly agree.

Box 7. Ongoing care and monitoring.

Statement 7.1: A personalised care plan should be in place for every patient with IBD, with access to an IBD nurse specialist and telephone/email advice line (consensus 97%: SA 61%, A 36%, N 3%).

Statement 7.2: Patients should be supported in self-management, as appropriate, through referral or signposting to education, groups and support (consensus 100%: SA 61%, A 39%).

Statement 7.3: Clear protocols should be in place for the supply, monitoring and review of medication across primary and secondary care settings (consensus 100%: SA 54%, A 46%).

Statement 7.4: Pain and fatigue are common symptoms for patients with IBD and should be investigated and managed using a multidisciplinary approach including pharmacological, non-pharmacological and psychological interventions where appropriate (consensus 100%: SA 61%, A 39%).

Statement 7.5: Any reviews and changes of treatment in primary or secondary care should be clearly recorded and communicated to all relevant parties within 48 hours (consensus 100%: SA 50%, A 50%).

Statement 7.6: Patients or parents/carers should be offered copies of clinical correspondence relating to their/their child’s treatment and care (consensus 100%: SA 61%, A 39%).

Statement 7.7: All patients with IBD should be reviewed at agreed intervals by an appropriate healthcare professional, and relevant disease information should be recorded (consensus 100%: SA 64%, A 36%).

Statement 7.8: A mechanism should be in place to ensure that colorectal cancer surveillance is carried out in line with national guidance and that patients and parents/carers are aware of the process (consensus 100%: SA 68%, A 32%).

A, agree; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; N, neither agree nor disagree; SA, strongly agree.

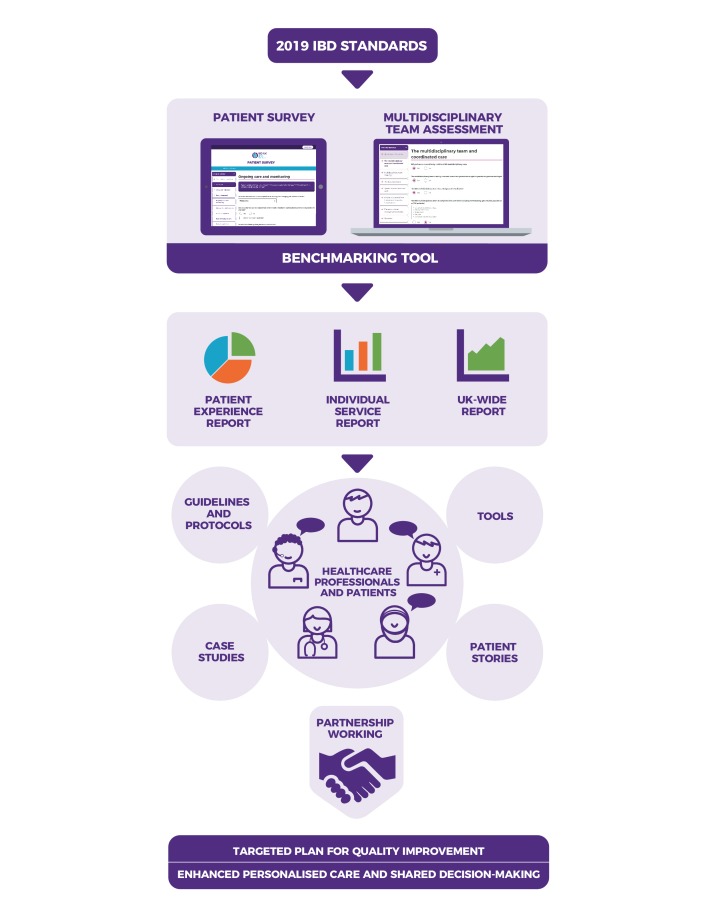

IBD Service Benchmarking Tool

In the online survey of 151 healthcare professionals, over 90% of respondents agreed that a benchmarking tool would be useful to support implementation of the IBD Standards. A new web-based tool has been developed to address this need (figure 2). The tool benchmarks against the revised IBD Standards and builds on the approach undertaken by the IBD Quality Improvement Project (IBD QIP) tool10 and the endoscopy Global Rating Scale.21 The unique strength of this tool is that both patient experience and service performance can be measured and benchmarked. This is achieved by a web-based self-assessment completed by the healthcare team and a different survey completed by patients.

Figure 2.

The IBD Service Benchmarking Tool. The 2019 IBD Standards form the basis for a web-based benchmarking tool with corresponding healthcare professional self-assessment and patient survey portals. Within this system, IBD services will be able to assess their own performance according to the Standards and see how they benchmark against other regional and national services. Healthcare professional self-assessment of their service can be presented alongside patient survey results for the same service across a range of domains. Quality improvement, personalised care and shared decision-making will be promoted through a range of online support tools, guidelines and case studies. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Within the Benchmarking Tool, the IBD Standards core statements (boxes 1–7) are represented across four domains of access, coordinated care, patient empowerment and quality. Each domain is subdivided into diagnosis, treatment, ongoing care and IBD service, with corresponding questions on both the patient survey and service self-assessment tool. Based on a set of agreed descriptors, gradings can be generated based on the results of the patient survey and through the service self-assessment process, ranging from ‘excellent, proactive’ to ‘minimal, inadequate’ care. Services will thereby be able to identify areas that clearly require quality improvement and to make the case for additional resources where needed. The benchmarking tool will enable clinical teams to compare self-assessment of service performance with patient experience across all domains, as well as with the UK average, the UK devolved nation average and the previous year’s results for the service. Additional resources will be available through the IBD UK website to support quality improvement (https://ibduk.org/).

Discussion

The development of these IBD Standards was essential as a benchmark against which IBD care can be measured. Compared with the second UK IBD Standards from 2013, the 2019 Standards differ substantially both in structure (reflecting the patient journey) and in content, as a result of substantial changes in service delivery in the last 6 years. The Standards reflect the increasing complexity of IBD management: the need for pre-treatment safety screening and therapeutic monitoring; the importance of shared decision-making between the IBD health professional team and the patient; the increasing involvement of Allied Healthcare Professionals, such as dietitians, psychologists and pharmacists, in the management of chronic disease patients; the need for partnership between hospitals, primary care and the patient in the delivery of care; and the growing use of technology to improve communication and patient education.

The Standards complement the recently published BSG and ACPGBI IBD guidelines.19 20 While these guidelines provide the evidence base and detail of current management, the Standards define a high-quality IBD service, including a number of objective measures of quality. This provides a cohesive and accessible framework for service development. The IBD Standards align with the 2015 NICE Quality Standard,9 providing much greater detail to support effective delivery of this.

The strengths of these Standards include the process by which they were developed. A strong expert consensus was achieved through a rigorous approach with representation across all relevant professional disciplines and UK stakeholders in IBD care, in addition to consistent input from patients and their organisations. The role of the patient organisation Crohn’s & Colitis UK in leading their development ensures that the primary focus is on the patient and their experience of care. Patient feedback was obtained at all stages of Standards development.

The Standards are laid out in an accessible form and cover many aspects of IBD service delivery that can be measured. Two tools were developed to assess the service: the benchmarking tool designed for professionals’ IBD service self-assessment and the survey tool designed for patients. Assessing a service both from the provider’s perspective and from that of the patients treated within that service is unique in IBD and may create an important tension for change in the absence of system-wide levers for service development.

There are limitations in the breadth of the evidence base used in formulating these Standards. For example, there are no data to validate the appropriate maximum time interval within which treatment can be started safely. However, the focus has been to define targets that are acceptable to patients and appropriate to the constraints of the NHS while being relevant also to other healthcare systems. The value of the IBD Standards is dependent on their implementation. The Standards define criteria that may not be achievable by every IBD service, but their purpose is to encourage service quality improvement. Fundamental to this is the recognition of the potential impact of improving patient care and outcomes at a local level, and the commitment of both healthcare professionals and patients to working in partnership to measure current delivery and effect meaningful change.

Following the launch of the IBD Standards in June 2019, the patient survey and IBD service web tool will be completed. Data will be collected through the IBD UK website, and the data controller will be Crohn’s & Colitis UK. The intention is for both patient survey and IBD service reports to be publicly available from the IBD UK website. The data will be used to inform IBD services and enable them to drive quality improvement, encouraging providers and patients to work in partnership.

Conclusion

The third UK IBD Standards comprise 59 consensus statements across seven clinical areas that make up the journey of patients with IBD. They have been developed by the IBD UK group, with patient involvement at all stages, and they represent the items that are necessary for delivery of a high-quality IBD service. They are integrated with current UK IBD guidelines and endorsed by relevant professional bodies. They are supported by benchmarking tools that are appropriate for use by healthcare professionals and by patients. Using these tools, services can measure their own performance, obtain feedback from patients and compare their service with others, with the overall aim of driving up the quality of services supporting patients with IBD.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to Richard Driscoll in acknowledgement of his outstanding impact on improving care for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. With thanks to David Barker for his role in establishing IBD UK. We are very grateful to all those who have contributed to the development of the IBD Standards and Benchmarking Tool, including Sophie Bassil, Sarah Berry, Jen Clifford and the wider Crohn’s & Colitis UK staff team, IBD UK’s patient members, Melissa Fletcher and Graham Bell, and people living with inflammatory bowel disease and parents/carers who have provided input and feedback at each stage of the IBD Standards and Benchmarking Tool development. This work was funded by Crohn’s & Colitis UK.

Footnotes

Twitter: @IBDUKTEAM

Contributors: The IBD Standards Development Group was composed of IDA, KJB, SB, FC, MF, OF, JG, ABH, RK, KK, JKL, AM, RM, NP, AStCJ and LY, with additional input from BJ, UM and CAL. Alignment of e-Delphi methodology with UK medical and surgical guidelines was undertaken by CAL and ABH. The e-Delphi voters were AGA, CA, IDA, KJB, GB, GB, SB, MJB, SRB, JD, AD, JE, OF, RF, MF, ABH, BJ, MJ, KK, JL, RM, AM, NP, GR, AStCJ, IS, SAT and LY. The Benchmarking Development Group was composed of IDA, KJB, SB, OF, JG, RK, KK, RM, NP, AStCJ, IS, SAT and LY. The patient survey development has been led by Crohn’s & Colitis UK. The manuscript was written by JG, ABH, RK and CAL. All members of IBD UK as co-authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript for submission: IBD UK organisational representative members were CA, IDA, KJB, SB, SJB, GB, GB, NB, AB, KC, RC, AD, JE, OF, VG, JG, ABH, RK, KK, UM, RM, AM, NP, AStCJ, SAT, SW, LY.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Hamilton B, Heerasing N, Hendy PJ, et al. PTU-010 prevalence and phenotype of IBD across primary and secondary care: implications for colorectal cancer surveillance. Gut 2018;67:A67–A. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones G-R, Lyons M, Plevris N, et al. DOP87 multi-parameter datasets are required to identify the true prevalence of IBD: the Lothian IBD registry (LIBDR). Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2019;13(Supplement_1):S082–S083. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy222.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ghosh N, Premchand P. A UK cost of care model for inflammatory bowel disease. Frontline Gastroenterology 2015;6:169–74. 10.1136/flgastro-2014-100514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burr NE, Lord R, Hull MA, et al. Decreasing Risk of First and Subsequent Surgeries in Patients With Crohn's Disease in England From 1994 through 2013. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2018. 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yu H, MacIsaac D, Wong JJ, et al. Market share and costs of biologic therapies for inflammatory bowel disease in the USA. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:364–70. 10.1111/apt.14430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The IBD Standards Group Quality Care: Service standards for the healthcare of people who have Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) : The IBD Standards Group. Oyster Healthcare Communications Ltd, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7. UK Inflammatory Bowel Disease Audit Steering Group IBD audit round one 2006-08, 2008. Available: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/ibd-audit-round-one-2006-08 [Accessed Apr 2019].

- 8. The IBD Standards Group IBD Standards 2013 Update, Crohn's & Colitis UK, 2013. Available: https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/improving-care-services/health-services/ibd-standards [Accessed Apr 2019].

- 9. NICE Inflammatory bowel disease quality standard 81, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs81/chapter/Introduction [Accessed Apr 2019].

- 10. Shaw I, Fernandez E. PWE-226 Are IBD services up to standard?—results from 1st round of the UK inflammatory bowel disease quality improvement project (IBD QIP): Abstract PWE-226 Table 1. Gut 2012;61(Suppl 2):A390.1–A390. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302514d.226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Royal College of Physicians UK inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) audit: round 4 (2012-2014), healthcare quality improvement partnership, 2014. Available: https://data.gov.uk/dataset/65eef566-030d-45b2-a0e9-884bea6807b5/uk-inflammatory-bowel-disease-ibd-audit-round-4-2012-2014 [Accessed Apr 2019].

- 12. Arnott I, Murray S. IBD audit programme 2005-2017. review of events, impact and critical reflections, Royal College of Physicians, 2018. Available: https://ibdregistry.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/IBD-audit-programme-2005–2017.pdf, [Accessed Apr 2019].

- 13. UK Inflammatory Bowel Disease Audit Steering Group IBD national report of the primary care questionnaire responses - round three 2012, Royal College of Physicians, 2012. Available: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/ibd-national-report-primary-care-questionnaire-responses-round-three-2012 [Accessed Apr 2019].

- 14. Rowse G, Hollobone S, Afhim S, et al. DOP30 Factors associated with life satisfaction in people with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: results from the national 2018 Crohn’s & Colitis UK Inflammatory Bowel Disease Quality of Life Survey. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2019;13 S042–43. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy222.064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Floyd DN, Langham S, Séverac HC, et al. The economic and quality-of-life burden of Crohn's disease in Europe and the United States, 2000 to 2013: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:299–312. 10.1007/s10620-014-3368-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, et al. IBD and health-related quality of life — discovering the true impact. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis 2014;8:1281–6. 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Irving P, Burisch J, Driscoll R, et al. IBD2020 Global Forum: results of an international patient survey on quality of care. Intest Res 2018;16:537–45. 10.5217/ir.2018.00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Quality Health National cancer patient experience survey, 2017. Available: http://www.ncpes.co.uk/index.php/reports/2017-reports [Accessed Apr 2019].

- 19. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown SR, Fearnhead NS, Faiz OD, et al. The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland Consensus Guidelines in Surgery for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Colorectal Disease 2018;20(Suppl. 3):3–117. 10.1111/codi.14448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Valori R. Reaching a consensus of what an endoscopy service should be doing: a critical step on the road to excellence in endoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol 2012;26:15–16. 10.1155/2012/487030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]