Abstract

Background

The judicialization of medicine can lead to professional disenchantment and defensive attitudes among surgeons. Some quantitative studies have investigated this topic in spine surgery, but none has provided direct thematic feedback from physicians. This qualitative study aimed to identify the impact of this phenomenon in the practice of spine neurosurgeons.

Methods

We proposed a qualitative study using grounded theory approach. Twenty-three purposively selected private neurosurgeons participated. Inclusion took place until data saturation was reached. Data were collected through individual interviews and analyzed thematically and independently by three researchers (an anthropologist, a psychiatrist, and a neurosurgeon).

Results

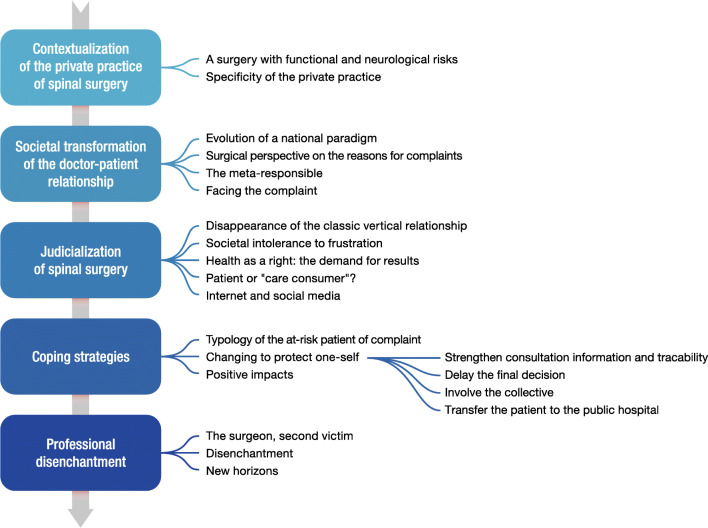

Data analysis identified five superordinate themes that were based on items that recurred in interviews: (1) private practice of spinal surgery (high-risk surgery based on frequent functional symptoms, in an unfavorable medicolegal context); (2) societal transformation of the doctor-patient relationship (new societal demands, impact of the internet and social network); (3) judicialization of spine surgery (surgeons’ feelings about the frequency and motivation of the complaints they receive, and their own management of them); (4) coping strategies (identification and solutions for “at risk” situations and patients); and (5) professional disenchantment (impact of these events on surgeons’ daily practice and career planning). Selected quotes of interviews were reported to support these findings.

Conclusions

Our study highlights several elements that can alter the quality of care in a context of societal change and the judicialization of medicine. The alteration of the doctor-patient relationship and the permanent pressure of a possible complaint encourage surgeons to adopt defensive attitudes in order to minimize the risks of litigation and increased insurance premiums. These phenomena can affect the quality of care and the privacy of physicians to the extent that they may consider changing or interrupting their careers earlier.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00701-020-04302-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Malpractice litigation, Practice pattern, Qualitative study, Spine surgery, Insurance liability, Burnout

Introduction

In a 2001 New York Times essay, a physician who had been through a long malpractice suit, proclaimed in a shock statement: “Now I think of the patient as the enemy” [33]. In several countries, negative effects of the judicialization of the doctor-patient relationship have been reported [25]. The deterioration in the quality of professional fulfillment on the part of practitioners has been reported whether they are sued or not, and the defensive strategies adopted have been described [29].

Spine surgery, in particular its degenerative component, is no exception to these predicaments due to the particular functional context and the risks concerning the underlying neurological structures [11]. Thus, claims in spinal surgery are frequent and costly because of the consequences on patients [10].

Our aim was to identify the impact of this societal and medicolegal shift among physicians who are particularly exposed because of their specialty. To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study that gives spine surgeons a direct voice to identify the perception of the judicialization of their daily practice.

Materials and methods

Because we wanted to explore surgeons’ perceptions about the impact of the judicialization of their practice, we chose to use the grounded theory approach as a general framework [28].

Participants and sampling

Interviews were performed between February and April 2019. Participants were private neurosurgeons, whose main activity was dedicated to spinal surgery [2]. Spine surgery is one of the main sources of claims with the highest costs according to data from medical insurers [14].

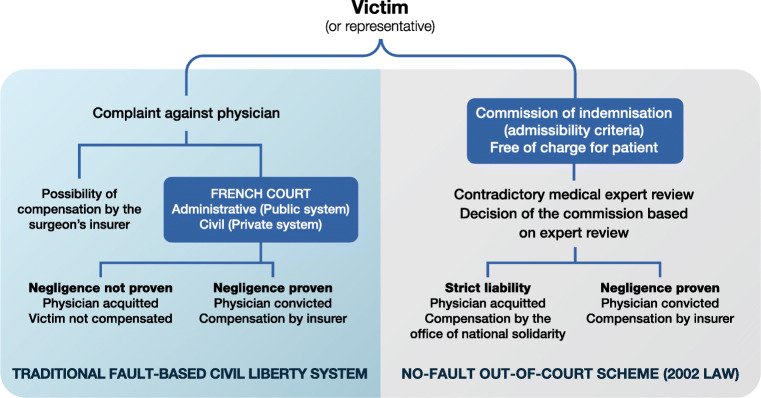

Since 2002, a complementary legal route to get compensation “quickly” and more easily was established with a new law [12]. This established the current French no-fault out-of-court scheme, and any patient can start it free of charge under admissibility criteria (Fig. 1). Private neurosurgeons are at the forefront of the medicolegal rise due to French law, which is more protective of public hospital surgeons [12].

Fig. 1.

Synoptic description of the French medicojudicial complaints system

According to the grounded theory methodology, a theoretical purposive sampling technique using maximum variation was used [22]. We interviewed surgeons of different ages, experience, and geographical locations of practice. We initially contacted 30 neurosurgeons, but the final sample size was determined by data saturation (i.e., the point at which no new themes emerged from the interviews), which occurred after 23 interviews [18].

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected through unstructured phone interviews by one researcher who did not know his interlocutors.

Each interview was transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis. After multiple readings of each verbatim, we developed the emergent themes following a series of coding steps. First, initial coding was generated by coding chunks of transcripts, keeping close to the participants’ words to isolate the basic units of meaning. Next, we identified relations between the initial codes and grouped them into categories according to their similarity. Lastly, these categories were organized into themes and subthemes. This inductive process (starting from the observation rather than from preexisting theories) was performed independently by three researchers with different backgrounds (an anthropologist, a psychiatrist, and a surgeon) so that we could triangulate our different perspectives and attend systematically to our own effects as researchers at each step of the process [15]. Consensus was reached during study meetings. We used NVIVO software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) during the process of analysis.

Both the Ethics Committee of the French College of Neurosurgery and the Data Protection Authority approved the study. The reporting follows the COREQ statement [31]. The participants provided informed consent before inclusion in the study and provide consent for their comments to be published.

Results

Data of participants

Theme saturation occurred after the 23rd interview (22 men and one woman). Participants had an average age of 52.5 years (range 39–68 years) and were working exclusively in private structures spread throughout the national territory. They had been working for an average of 22 years (8–35 years). They operated on an average of 450 patients per year (range 300–650).

The thematic areas

Data analysis identified five superordinate themes that were based on items that recurred in interviews (Fig. 2). The themes are analyzed in detail in the following section, and selected quotes of the interviews are reported to support our findings, with more examples in Table 1 and Appendix (Online Resource). Quotes are close translations that retained the feel of the spoken language.

Fig. 2.

Description of the main themes and subthemes

Table 1.

Main themes, selected subthemes, and quotations referring to them

| Main themes | Subthemes | Selected quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Contextualization of the private practice of spinal surgery | Particularity of the private practice |

They know that in Hospital they are covered, that the Hospital will take care of it, actually many of them do not even attend expert assessments themselves if they work in the hospital... well yes it’s a Hospital so there’s the medical adviser, the lawyer who represents the Hospital, every so often the practitioner but not always... Surgeon_7 |

| Societal transformation of the doctor-patient relationship | Health as a right: the demand for results |

Whatever specialists or legal experts or angelic people might say, we are slipping away from an obligation of means to an obligation of result. Surgeon_1 |

| Judicialization of spinal surgery | Surgical view of the motivations behind complaints |

I’ve seen it when it comes to expert reviews, there are lots of cases that are not justified, yeah, it really is nonsense. Surgeon_11 |

| The meta-responsible |

It’s hard when you go to an expert review because you know that you are going to be judged, that you are going to be judged not impartially but aggressively by most of the people who are there, because there’s someone with the status of victim and then there’s you, the surgeon, a priori considered guilty Surgeon_10 |

|

| Coping strategies | Strengthen consultation information and trackability |

It does not necessarily benefit the patient, but the surgeon will be protected on file, you see, they’ll have ticked that box. That represents an important change in practices, that is to say, we are not doing it for the patient but rather in order to protect ourselves. Surgeon_1 |

| Transfer the patient to the public hospital |

Whenever there are patients who I consider to be too risky to treat privately because I would be too exposed to liability, then indeed, I prefer to refer them to the university hospital. Surgeon_9 |

|

| Professional disenchantment | Disenchantment |

Again, it does affect me. I’ll tell you this now actually, I was thinking about it on the way home earlier- For me, it’s one of the things, you know, well now I’m approaching retirement age, I can tell you I’ll hang in there for one, two, five more years... but if anything were to make me quit earlier it would be that. It’s unbearable. You reach a point where it becomes... well, you try to do your job well, you work hard, but you get knocked back sometimes like everyone else and you are systematically being blamed... I reckon that at the moment, at my age, that’s the part of the job that bears down on me the most. Surgeon_5 |

| New horizons |

In other countries, surgeons are working in great conditions: they work much less because their fees are much higher and fuck, they are chilled, they are relaxed! Surgeon_11 |

A larger selection of quotes is available in Appendix as Electronic Supplementary Material

Theme 1: Contextualization of the private practice of spinal surgery (Online Resource 1)

A surgery with functional and neurological risks

All participants referred to the random nature of surgical outcomes based on functional and subjective symptoms, subject to the impact of personal contexts. Spine surgery would involve an incompressible percentage of imperfect outcomes that favor post-operative disappointments and raise the challenge of preoperative communication.

Moreover, they pointed out the neurological risk inherent in any spinal procedure, with deficits that can be severe.

It’s a type of surgery with results that are not 100%… so we know very well that a certain percentage of people won’t be fully satisfied. (Surgeon_13)

Specificity of the private practice

Participants pointed out that the public system is much more protective because it is covered by administrative law. They felt more exposed in private practice with a far more significant psychological impact. They also unanimously refer to the impact of claims on the continuous increase in their insurance premiums, which could influence defensive behaviors.

… these issues with complaints have caused an increase in insurance prices, and changes in our practices... (Surgeon_8)

Theme 2: Societal transformation of the doctor-patient relationship (Online Resource 2)

Disappearance of the classic vertical relationship

Many participants mentioned a societal change characterized by a questioning of former elites (intellectual, political, religious, etc.), including surgeons. Interactions have become less respectful and marked by a questioning of their expertise.

It does feel like nowadays that image is no longer the same as it used to be and that there is probably less respect, less understanding with regard to the difficulties of our profession, there are patients who consider that we are there to fix them just like you would fix a car... (Surgeon_8)

Societal intolerance to frustration

Patients are representative of a new society based on speed and intolerance to frustration, a world based on an individualistic quality of life, with negative resonances on the doctor-patient relationship.

Nowadays nobody can stand the slightest complication, the slightest delay, the slightest problem. (Surgeon_1)

Health as a right: the demand for results

Most surgeons insisted on this societal mutation making health a right, which causes a “tacit shift from the obligation of means to the obligation of result” (Surgeon_1). Many used the image of a “mechanical repair,” implying guaranteed results, challenging the informed consent and placing the surgeon in the role of the person responsible for any disappointing results.

Good health is no longer a privilege but a right, and that has a terrible impact on the patients’ relationship with their illness, their pain, their sequelae… (Surgeon_19)

Patient or “care consumer”?

Health has become like a consumer good; therefore, the surgeon is seen as a supplier whose result can be demanded and held accountable because he is paid, in a country where, paradoxically, access to health is not very expensive.

Nowadays people gladly go to the doctor, as if they were going to a shop, to be supplied with something basically… (Surgeon_15)

Internet and social media

The Internet provides non-selective access to information that can interfere with the physician’s explanations and call into question his or her conclusions. Some feel their expertise is being questioned, facing an alternative truth acquired online by the patient. In addition, forums can provide unfavorable information about clinicians who may find themselves rated just like hotels or restaurants. The time acceleration of a society where everything is within a click’s reach also alters the singular colloquium.

People want everything, right away, it’s the internet society where you can order stuff in just a click, basically now everything is just a click away. (Surgeon_12)

Theme 3: Judicialization of spinal surgery (Online Resource 3)

Evolution of a national paradigm

Surgeons described a judicialization of their job that they believe follows the US model, following a distrust with patients who would see medical error or fault everywhere. Several highlighted the 2002 law, whose perverse effect was to facilitate the initiation of a complaint by the patient that often may not be justified. These complaints and their consequences become an important part of everyday professional life when they should not be.

it’s good, except that the procedure is completely free, you just go online, fill in a form and that’s it, and that has made the number of complaints rise (Surgeon_2)

Surgical perspective on the reasons for complaints

Most participants agreed that there is a financial motivation for a claim for compensation. Nevertheless, resentment due to a lack of explanation or the feeling that the physician may hide elements can also lead to a complaint process, as well as poor clinical results, which raises the problem of preoperative information.

The meta-responsible

Surgeons saw themselves as an ideal perpetrator, symbolically the one who performs the aggressive act. During the medical expert review, the patient would immediately have the status of “victim” and the surgeon that of “guilty” until proven otherwise, because, despite the concept of hazards, the patient and his/her relatives need to designate a responsible person.

The culprit will always be the one who performs the aggressive act... it’s always the surgeon. (Surgeon_1)

Facing the complaint

When a new complaint is announced, physicians described feelings of discouragement, injustice, or anger if they feel that this is not justified. There is also a feeling of helplessness facing the judicial machinery. The result is an acute stress during the procedure, which is unanimously described as not only anxiogenic, but also chronic, now intrinsic to professional practice. These painful situations are experienced as unavoidable.

My old colleagues told me I’d get used to it over time, but I feel like it’s the opposite- the more it goes on, the more it gets me down. (Surgeon_2)

Theme 4: Coping strategies (Online Resource 4)

Typology of the patient at risk of complaint

Participants identified patients at risk but remained critical of their own a priori. Some professions, communities, comorbidities, or associated pathologies were often mentioned as being at risk of conflict, but two groups stood out: suspicious and aggressive patients during the consultation and patients covered by universal insurance. Physicians associated free healthcare with reckless demands and claim risk. Beyond these defensive mistrusts, several participants insisted on the fact that these a priori should not be generalized.

Changing to protect oneself

The adoption of defensive tactics is widespread, with a new way of reasoning for indications and tracking information in the medical file. For many, it is a question of acting more in relation to the medicolegal risk rather than purely in the medical interest of the patient. This implies a change in practices: (i) strengthening consultation information, informed consent, and trackability (at the risk of turning a relationship of trust into distrust); (ii) delay in the final decision (by increasing the number of consultations before surgery); (iii) involvement of the collective (by developing boards discussions, in a dual scientific and medicolegal interest); and (iv) patient referral to the public hospital (not because of technical incompetence but because the public physician will be better protected there).

That’s sort of the perverse side in terms of public health—we increasingly find ourselves treating people based on the medico-legal risks rather than the interests of the patient on a purely medical level (Surgeon_6)

Positive impacts

Some physicians did not perceive this situation as only negative, by imposing new professional standards, breaking with the image of the “omniscient and solitary” surgeon (Surgeon_1).

I don’t believe that everything is necessarily bad in the judicialization of doctor-patient relationships. (Surgeon_9)

Theme 5: Professional disenchantment (Online Resource 5)

The surgeon, second victim?

Surgeons pointed out an insidious pressure, which is permanently interfering in their daily lives, even outside working hours. This negative pressure is in addition to the intrinsic pressure of complex surgeries and can lead to a loss of motivation and professional disengagement.

you think about it in the evening, at the weekend, at night, it happens a lot especially at times when you’re already feeling down, you do think about it often (Surgeon_9)

Disenchantment

Gradually, this negative pressure exerts an undermining effect and deteriorates the pleasure of operating, as well as the relationship with others. A growing fatigue is developing, which can either precipitate an early retirement decision or even lead the surgeon to another career. Some even mentioned a “dark side” of the profession.

I’m probably less tolerant of people constantly complaining, but then again on the other hand it is probably not such a bad thing because it will enable me to retire. (Surgeon_14)

New horizons

Several physicians evoked the possibility of changing paths, or exercising differently in the face of this pressure, which alters their professional pleasure. Among the interviewees, several mentioned a move abroad to work with less pressure or undervalued conditions; others consider a career change (start-up, lawyer...), or even becoming a judicial expert.

Often you think to yourself: damn they’re so annoying, should I carry on working, or should I be doing something else, a less complicated job… (Surgeon_9)

Discussion

This qualitative study, carried out according to the COREQ guidelines [31], demonstrates that the judicialization of surgical practice, in a context of societal change, provokes an alteration of the doctor-patient relationship and a perceived insecurity, leading surgeons to consider coping strategies, defensive practices, and even interrupting or modifying their careers.

A changing relationship

Did the interviewed surgeons overlook a global societal change [32]? The timeless doctor-patient relationship has recently undergone drastic changes: strengthening of patients’ rights, Internet and social networks, societal transformations in the relationship to authority and knowledge [30]. The surgeon, heir to macho heroes, historically carries a particular aura and a tradition of powerful ego [8]. The societal changes mentioned above impact this position of knowing and it seems that interviewees are destabilized by the acceptance of this paradigm shift, and have difficulty accepting the demotion of their social positioning within the new medical democracy [27].

Nevertheless, surgery remains an experience without equivalent in other professions, i.e., a procedure where the same act can greatly improve or irremediably alter a function or quality of life [22]. A gap may arise between a technically successful surgery and the secondary disappointment of a result that is ultimately partial or even absent [16].

It may seem paradoxical that private surgeons (who were therefore monetizing their skills more expensively for patients than at the public hospital) complain that these patients have become “health consumers.” There is however a feeling of downgrading with expertise becoming a simple service [24]. This societal mutation, which is at the core of surgeons’ concerns, still has difficulty being accepted and adaptive procedures are experienced in an unfavorable way. What emerges from most of the interviews remains a decrease in empathy for the patient and a change in the healthy relationship between surgeon and patient, whether or not a problem occurs, whereas this relationship itself may be the most powerful antidote to this alteration that medicine can provide [25]. None of the interviewees mentioned any particular training or willingness to face this problem in a group, as it may exist in other disciplines [9].

A perceived professional insecurity

Surgeons obviously identify the complexity of patients’ expectations, which can be very different from the functional outcome, not to mention possible neurological sequelae [3, 35]. Moreover, several physicians highlighted a tacit shift for patients from the obligation of means to the obligation of result: bad results are no longer tolerated, and this can lead to defensive practices. The patient is not seen as an “enemy” [33], but socio-professional subgroups are designated as at risk and induce the physician’s mistrust or outright refusal of care. It has been shown, particularly in the USA, that the poorest patients were under-represented among the complainants [7, 19], contrary to a stereotypical idea found in the interviews with the surgeons in our study. That said, the national systems are not the same, and it should be pointed out that, in France, the 2002 law system has made it easy for patients to initiate a complaint free of charge, which, even if it will not often lead to the effective demonstration of a fault, remains the dark side of the profession and impacts the lives of most practitioners, like a “sword of Damocles” [12].

Analysis of data from the French main insurance company demonstrates that only 15% of the expert reviews conclude that the case is unfavorable to the surgeon [14]. Is this negative pressure of a possible litigation really justified? In other words, are physicians the victims of “irrational fears” or are they, on the contrary, lucid observers of changes in patient behaviors? Several studies have highlighted this gap between “real risk” and “perceived risk” and the term “litigaphobia” has even been coined to define this concept [6]. It is nevertheless revealing to note that the path chosen by the French plaintiffs is a simple conciliation in only 15% of cases for spine surgery while it is in 50% of cases for all specialties combined [14], which clearly shows that in the particular field of spinal surgery, the complaint process immediately takes a more threatening turn for the physician.

From disappointment to frustration

Physicians have therefore adopted coping strategies, while recognizing that these strategies could be detrimental to the quality of care, with the advent of defensive practice [17]. Nahed et al. had shown that 45% of 3344 neurosurgeons surveyed eliminate high-risk procedures from their practice due to liability issues [20]. In our interviews, there are no integral defensive behaviors as described in the USA for spine surgeons [11], but there is a first draft, at least, on the selection of patients and on the avoidance of certain high-risk patients for major surgeries. It is interesting to note that some interviewees can transfer a patient to another facility (essentially public) not for technical incompetence but because the colleague will be better covered in case of complaints, a practice found in other countries and other health systems [34].

The fact that their specialty is included in the top ranking of risk specialties can generate a feeling of injustice and a permanent feeling of “medicolegal insecurity,” preventing serene practice [4, 11]. The underlying presence of this threat may alter the physician’s career satisfaction and lead to serious psychological symptoms. Doctors who have received few or no complaints also report the same potential threat of litigation, which contributes to growing professional frustration [13]. This perceived risk is a significant stressor that can lead to compassion fatigue, directly correlated to reduced empathy toward patients. Clinical performance and the doctor-patient relationship are affected. Data suggested that accelerated burnout and depression re-occur in a vicious circle leading to worsening patient care and higher risk of adverse events [1]. Surgeons are often in an isolated position in the face of their chronic professional suffering: Even if recent steps, within institutions and via insurance companies, have been proposed to prevent and support practitioners in this kind of situation, there is still a long way to go in a profession marked by the culture of individualism and by a relationship of distrust with the administrations [23, 26].

In a survey of 2999 Australian physicians, Nash et al. demonstrated that concerns about medicolegal issues led to 33% of them considering giving up medicine, 32% reducing their working hours, and 40% retiring early [21]. We also find these considerations among our interviewees, referring to retirement as a relief, even considering it early on, or even considering redirecting their career to a less exposed profession, even as a lawyer [5].

Possible paths for improvement to overcome disenchantment

If this societal mutation seems inevitable, it is legitimate to propose axes to avoid unfavorable experiences for patients, public health, and physicians. Elements of law and medicolegal strategies should be better integrated from primary education onwards to prevent rather than cure, as well as in continuing education. Practicing in a group, sharing experiences and cases, and cases and taking part in morbidity boards are a major help in avoiding unfavorable decisions and defensive practices. Support groups should intervene to prevent a surgeon from being isolated in the event of litigation, whether they are responsible or not [10]. The doctor-patient relationship must remain at the center of our efforts, but unfortunately the busy schedule of private medicine is sometimes incompatible with the availability that each patient requires [25].

Limitations

Reading a qualitative study can be disconcerting for the reader accustomed to the quantified results [28]. We believe that these still rare approaches in spine surgery are an essential complement to the classic studies assessing our demanding daily practice. The qualitative approach used in this study allows hypotheses to be formulated but is not designed to confirm them.

Our sample may seem very specific, but in fact, private surgeons are very vulnerable in our judicial system. We therefore believe that their experience is similar to that of other surgeons in other countries’ judicial systems and health systems, and therefore that the expression of their feelings can be transposed [22].

Conclusion

Our study makes it possible to detail the discomfort within a profession that experiences a as double exposure: first, not only because of the high-risk nature of spinal surgery but also because of a breach of trust in the traditional doctor-patient relationship in a context of societal evolution and judicialization, which is actually more felt than real.

However, the impact on everyday professional life is no less important, both in the quality of the human relationship with a patient who may be felt as a consumer or a threat, and then with regard to indications with drafts of defensive conduct and a loss of motivation for exercising the profession.

If we can talk about a reconfiguration of a profession toward new modes of practice, the disenchantment in everyday life is undeniable. Unfortunately, little appropriate support for these issues is currently available for practitioners, who do not seem to be specifically asking for it.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 88 kb)

(PDF 93 kb)

(PDF 94 kb)

(PDF 105 kb)

(PDF 85 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ellie McArthur for translating the oral quotations of the participants, and Editage for the English language edition of the manuscript. We are very grateful to Adrianne Brunet for the transcription and formatting of the interviews, and to Guillaume Lonjon for his judicious review of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Spine - Other

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abd Elwahab S, Doherty E (2014) What about doctors? The impact of medical errors. Surgeon. 10.1016/j.surge.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Activité établissements Activité établissement - Casemix MCO | Stats ATIH. https://www.scansante.fr/applications/casemix_ghm_cmd?secteur=MCO.%20Activite%CC%81%20e%CC%81tablissement%20%E2%80%93%20Casemix%20MCO%20|%20Stats%20ATIH. Accessed 9 Nov 2019

- 3.Andersen SB, Birkelund R, Andersen MØ, Carreon LY, Coulter A, Steffensen KD. Factors affecting patient decision-making on surgery for lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 2019;44(2):143–149. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balch CM, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, Colaiano JM, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Personal consequences of malpractice lawsuits on American surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(5):657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharya S. Can competition and the fear of litigation drive one to retirement? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(6):601–602. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breslin FA, Taylor KR, Brodsky SL. Development of a litigaphobia scale: measurement of excessive fear of litigation. Psychol Rep. 1986;58(2):547–550. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1986.58.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burstin HR, Johnson WG, Lipsitz SR, Brennan TA. Do the poor sue more? A case-control study of malpractice claims and socioeconomic status. JAMA. 1993;270(14):1697–1701. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.14.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassell J. Dismembering the image of god: surgeons, heroes, wimps and miracles. Anthropol Today. 1986;2(2):13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalton GD, Samaropoulos XF, Dalton AC. Effect of physician strategies for coping with the US medical malpractise crisis on healthcare delivery and patient access to healthcare. Public Health. 2008;122(10):1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels AH, Ruttiman R, Eltorai AEM, DePasse JM, Brea BA, Palumbo MA. Malpractice litigation following spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;27(4):470–475. doi: 10.3171/2016.11.SPINE16646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Din RS, Yan SC, Cote DJ, Acosta MA, Smith TR. Defensive medicine in U.S. spine neurosurgery. Spine. 2017;42(3):177–185. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.G’Sell-Macrez F. Medical malpractice and compensation in France, part I: the French rules of medical liability since the patients’ rights law of March 4, 2002. Chicago-Kent Law Rev. 2011;86(3):1093. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawthers AG, Localio AR, Laird NM, Lipsitz S, Hebert L, Brennan TA. Physicians’ perceptions of the risk of being sued. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1992;17(3):463–482. doi: 10.1215/03616878-17-3-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MACSF.fr Macsf. In: MACSF.fr. https://www.macsf.fr/Rapport-annuel-sur-le-risque-medical/risque-des-professions-de-sante. Accessed 8 Jan 2020

- 15.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGirt MJ, Bydon M, Archer KR, et al. An analysis from the quality outcomes database, part 1. Disability, quality of life, and pain outcomes following lumbar spine surgery: predicting likely individual patient outcomes for shared decision-making. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;27(4):357–369. doi: 10.3171/2016.11.SPINE16526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mello MM, Studdert DM, DesRoches CM, Peugh J, Zapert K, Brennan TA, Sage WM. Caring for patients in a malpractice crisis: physician satisfaction and quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(4):42–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morse JM. Data were saturated . . . Qual Health Res. 2015;25(5):587–588. doi: 10.1177/1049732315576699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulcahy L. Disputing doctors: the socio-legal dynamics of complaints about medical care. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nahed BV, Babu MA, Smith TR, Heary RF (2012) Malpractice liability and defensive medicine: a national survey of neurosurgeons. PLoS One. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Nash LM, Walton MM, Daly MG, Kelly P, Walter G, van Ekert EH, Willcock S, Tennant C. Perceived practice change in Australian doctors as a result of medicolegal concerns. Med J Aust. 2010;193(10):579–583. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb04066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orri M, Revah-Lévy A, Farges O (2015) Surgeons’ emotional experience of their everyday practice - a qualitative study. PLoS One. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Pinto A, Faiz O, Bicknell C, Vincent C. Surgical complications and their implications for surgeons’ well-being. BJS. 2013;100(13):1748–1755. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rada RT. The health care revolution: from patient to client to customer. Psychosomatics. 1986;27(4):276–279. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(86)72702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roter D. The patient-physician relationship and its implications for malpractice litigation. J Health Care Law Policy. 2006;9(2):304. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(7):678–686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw J, Baker M. “Expert patient”—dream or nightmare? BMJ. 2004;328(7442):723–724. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7442.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starks H, Brown Trinidad S. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1372–1380. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, DesRoches CM, Peugh J, Zapert K, Brennan TA. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2609–2617. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabibian BE, Kuhn EN, Davis MC, Pritchard PR. Patient expectations and preferences in the spinal surgery clinic. World Neurosurg. 2017;106:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truog RD. Patients and doctors — the evolution of a relationship. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):581–585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1110848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verghese A (2003) The way we live now: 3-16-03; Hard Cures. The New York Times

- 34.Yan SC, Hulou MM, Cote DJ, Roytowski D, Rutka JT, Gormley WB, Smith TR. International defensive medicine in neurosurgery: comparison of Canada, South Africa, and the United States. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yee A, Adjei N, Do J, Ford M, Finkelstein J. Do patient expectations of spinal surgery relate to functional outcome? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(5):1154–1161. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0194-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 88 kb)

(PDF 93 kb)

(PDF 94 kb)

(PDF 105 kb)

(PDF 85 kb)