Abstract

General anaesthesia is sometimes favoured over regional anaesthesia in ophthalmic surgery. The use of supraglottic airway (SGA) or laryngeal mask airway (LMA) as the primary airway device is increasing due to numerous advantages over tracheal intubation. Compared with 1st generation SGAs, 2nd generation SGAs have an added benefit of isolating the airway from the alimentary tract. However, the vertical profile of SGAs may encroach into the surgical field and hence interfere with surgery. We investigated the vertical projections of 1st generation SGAs (LMA Classic, Ambu AuraFlex) and commonly used 2nd generation SGAs in our institution (LMA ProSeal, LMA Supreme, LMA Protector, Ambu AuraGain and I-gel) in a manikin model. Each device was connected to a corrugated catheter mount or angled connector following insertion as per usual clinical practice in our institutions. Vertical projections of all devices were measured from the chin using a centimetre ruler. Securing of airway device to the chin with an adhesive tape was possible for the LMA Classic and Ambu AuraFlex with straight corrugated connector, whereas the stiffer 2nd generations SGAs required the addition of an angled connector or straight corrugated tubing to direct the airway tube caudally, away from the surgical field. The LMA ProSeal had the lowest vertical projection amongst the 2nd generation SGAs and may be the suitable choice for ophthalmic surgery. We also describe a novel technique of utilising a 1st generation SGA with placement of an orogastric tube, although with some reservations. This study has several limitations and transferability of our findings into clinical practice is questionable as the use of a manikin may not fully imitate the real condition of the patient. Our study is the first study comparing vertical projected height of different SGAs in manikin, but future studies should investigate the use of SGA in the clinical setting during ophthalmic surgery.

Keywords: General anaesthesia, Laryngeal mask airway, Supraglottic airway, SGA, SAD, Ophthalmic anaesthesia

Introduction

Most of ophthalmic routine surgery, such as cataract and glaucoma operations, may be performed under topical or regional anaesthesia [1]. However, certain patients and surgical factors may favour general anaesthesia, for example, in patients with severe dementia, severe Parkinsonism, claustrophobia, in the paediatric cohort, prolonged duration of surgery (vitreoretinal or corneal transplantation), ocular trauma and patient’s refusal for regional anaesthesia. Optimal airway management is crucial in eye surgery because the airway may remain inaccessible throughout the procedure. Any need to adjust or reposition the airway device during surgery could cause hypoxia, hypercarbia or disruption to the surgery. A secure airway by means of endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation aided by neuromuscular blocker is commonly perceived to be the gold standard technique. Unfortunately, laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation as well as extubation are associated with coughing, increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure and, ultimately, raised intraocular pressure [2] which may be undesirable in ophthalmic surgical patients. The introduction of classic laryngeal mask airway (LMA), also described as supraglottic airway (SGA) or supraglottic airway device (SAD) in clinical anaesthesia during the mid-1980s led to its increased use in short to medium duration ophthalmic surgical procedures because SGAs were known to reduce the unwanted effects of endotracheal intubation and extubation [3, 4]. It was possible to secure the SGA in a similar fashion as an endotracheal tube without obstructing surgery. Patients can breathe spontaneously or receive positive pressure ventilation through the SGA. In spontaneously breathing patients, it is not unusual to observe hypercapnoea due to a reduction in minute ventilation as a result of respiratory depression by anaesthetic agents and opioids. Hypercapnia for prolonged periods may have deleterious effects on intra-ocular pressure [5]. Furthermore, if the depth of anaesthesia is inadequate, the globe may be in a rotated position thereby making surgery difficult. This may lead to an increased incidence of coughing and obstructed airway. Controlled ventilation through the SGA with the help of neuromuscular blockade has been employed to achieve the best optimum condition for eye surgeries [6] and may aid tighter control of ocular physiology. Unfortunately, the 1st generation LMAs (e.g. both LMA Classic and the later version of flexbile SGAs such as the Ambu AuraFlex) may not guarantee a secure airway and there is an additional risks of aspiration of gastric contents in some patients (high body mass index, history of gastro-oesophageal reflux or undiagnosed hiatus hernia), especially during positive pressure ventilation [7]. There is a fear in the anaesthesia community that LMA Classic may soon be commercially unavailable because of its decreasing use with the concomitant increasing use of the 2nd generation SGA. The 2nd generation SGA have separate channels for the airway and the alimentary tract [8], and are recommended in international difficult airway guidelines [9]. Although the 2nd generation SGAs have improved design and in safety features, they are difficult to secure on the chin in similar fashion as endotracheal tubes due to raised vertical projection (e.g. hard bite block) which encroach into the operating field and may interfere with instrumentation during surgery.

We aimed to investigate vertical projections of LMA Classic, Ambu AuraFlex and various 2nd generation SGAs in a manikin.

Methodology

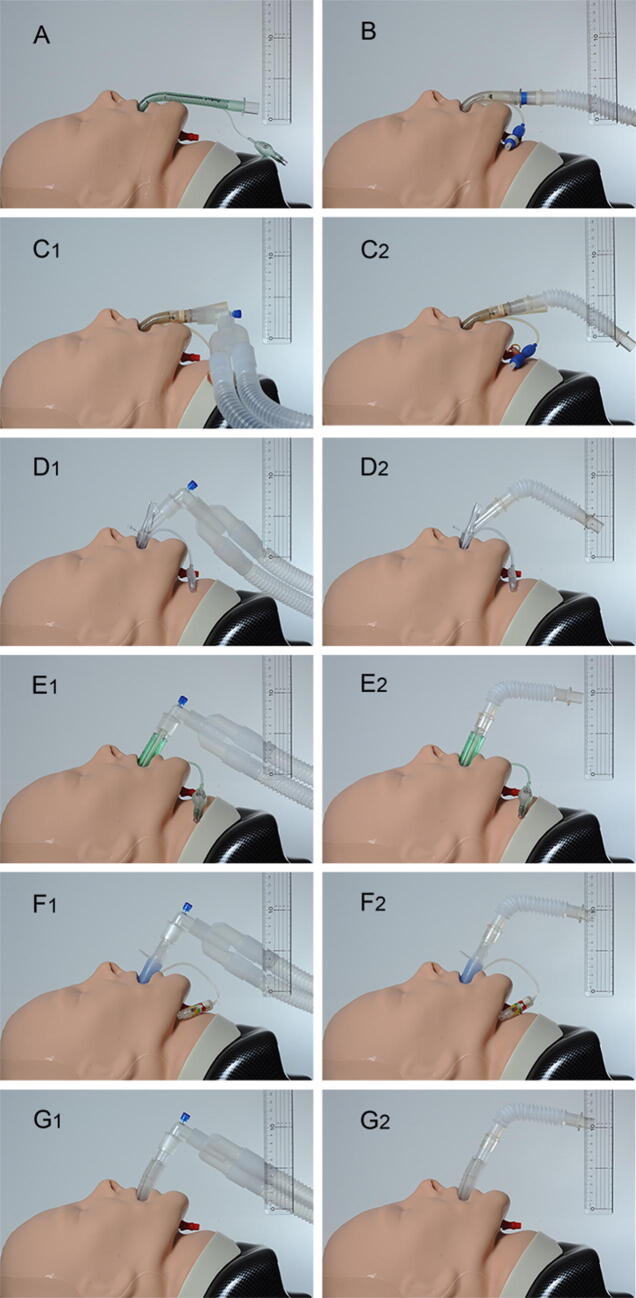

The local research and ethics committee has given written exemption approval as it is considered unnecessary since it is a technical non-patient, in vitro manikin study. One anaesthetist (JM) placed LMA Classic, Ambu AuraFlex and 2nd generation SGAs (all size # 4) which were available in our operating theatre, using an AirSim airway manikin (TruCorp, Craigavon, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom). After the placement of the device, an attempt was made to secure them to the chin by an adhesive tape. Difficulties in securing the device to the chin were noted. Each device was connected to a corrugated straight catheter mount or angled connector if considered suitable in a bid to reduce the vertical profile. Vertical projections of all devices were measured from the chin using a plastic centimetre ruler and were photographed at a fixed distance from the camera lens to manikin using a Nikon 85 mm D700 SLR camera (Fig. 1). All photographs were combined using Adobe Photoshop CC 2017 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, California, USA). No image editing was allowed.

Fig. 1.

a Ambu AuraFlex with corrugated connector; b LMA Classic with straight corrugated connector; c1 LMA ProSeal with angle connector; c2 LMA ProSeal with corrugated connector; d1 LMA Supreme with angle connector; d2 LMA Supreme with corrugated connector; e1 Ambu AuraGain with angle connector; e2 Ambu AuraGain with corrugated connector; f1 LMA Protector with angle connector; f2 LMA Protector with corrugated connector; g1 I-gel with angled connector; g2 I-gel with straight corrugated connector

Results

Securing of airway device to the chin with an adhesive tape was possible for the LMA Classic and Ambu AuraFlex. The hard plastic or silicone bite block of the 2nd generation devices prevented securing to the chin. The height of projection of all evaluated devices are included in Table 1. Vertical height projection was favourable for the Ambu AuraFlex (3.4 cm), the LMA Classic (3.8 cm) and LMA ProSeal 4.5 cm (angled connector) to 5.9 cm (corrugated connector). Less desirable vertical heights were found for the LMA Supreme 9.5 cm (angled connector) to 9.8 cm (corrugated connector), the Ambu AuraGain 9.9 cm (angled connector) to 11.6 cm (corrugated connector), the LMA Protector 11.0 cm (angled connector) to 12 cm (corrugated connector) and the I-gel 11.8 cm (angled connector) to 13.1 cm (corrugated connector).

Table 1.

Type of SGA, manufacturers, material of SGA, difficulties encountered in securing to the chin and vertical projected heights

| Supraglottic airway | Manufacturer | Figure | Bite block | Material of device | Was it possible to secure the device to the chin? | Vertical projection (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambu AuraFlex with corrugated connector | Ambu A/S, Ballerup, United Kingdom | A | No | Polyvinyl chloride | Yes | 3.4 |

| LMA Classic with straight corrugated connector | Teleflex Medical, Westmeath, Ireland | B | No | Silicone | Yes | 3.8 |

| LMA Proseal with angle connector | Teleflex Medical, Westmeath, Ireland | C1 | Yes | Silicone | Possible with difficulty | 4.5 |

| LMA ProSeal with corrugated connector | Teleflex Medical, Westmeath, Ireland | C2 | Yes | Silicone | Possible with difficulty | 5.9 |

| LMA Supreme with angle connector | Teleflex Medical, Westmeath, Ireland | D1 | Yes | Polyvinyl chloride | No | 9.5 |

| LMA Supreme with corrugated connector | Teleflex Medical, Westmeath, Ireland | D2 | Yes | Polyvinyl chloride | No | 9.8 |

| Ambu AuraGain with angle connector | Ambu A/S, Glen Burnie, Maryland, USA | E1 | Yes | Polyvinyl chloride | No | 9.9 |

| Ambu AuraGain with corrugated connector | Ambu A/S, Glen Burnie, Maryland, USA | E2 | Yes | Polyvinyl chloride | No | 11.6 |

| LMA Protector with angle connector | Teleflex Medical, Westmeath, Ireland | F1 | Yes | Silicone | No | 11.0 |

| LMA Protector with corrugated connector | Teleflex Medical, Westmeath, Ireland | F2 | Yes | Silicone | No | 12.0 |

| I-gel with angled connector | Intersurgical Ltd, Berkshire, United Kingdom | G1 | Yes | Styrene ethylene butadiene styrene | No | 11.8 |

| I-gel with straight corrugated connector | Intersurgical Ltd, Berkshire, United Kingdom | G2 | Yes | Styrene ethylene butadiene styrene | No | 13.1 |

Discussion

Our study helped to highlight the practicality and limitations of the design of each SGA in ophthalmic surgery. The LMA Classic and the Ambu AuraFlex are the two widely used 1st generation SGAs. The long and flexible part of airway tube of the 1st generation SGAs allows the anaesthetists to secure the tube to the chin away from the surgical site in the same way as an the endotracheal tube, thereby maximising the operating field and minimising interference to the surgeon. However, the use of mechanical ventilation through 1st generation SGAs for surgeries lasting more than 2 h may not be appropriate, due to the increased risk of gastric insufflation and possible aspiration. To mitigate this risk, an orogastric tube can be inserted prior to SGA placement to allow for gastric decompression (Fig. 2). A drawback of this technique is that the indentation of the SGA cuff created by the orogastric tube can result in an increased leak and lower seal pressures during positive pressure ventilation, resulting in unreliable ventilation and anaesthetic gas delivery.

Fig. 2.

Legend: LMA Classic with an orogastric tube

The 2nd generation SGAs such as the LMA ProSeal, LMA Supreme, AuraGain, LMA Protector and I-gel are designed to provide safer mechanical ventilation for longer periods thanks to a separate gastric channel, compared to their 1st generation counterparts. The cuff designs confer higher seal pressures and a built-in drainage port allows the insertion of a gastric tube through the gastric channel for gastric decompression. Presence of gastric fluid within the drainage port also serves as an early warning of regurgitation allowing for prompt management to avoid pulmonary aspiration. Appropriate use of SGA is not associated with increased aspiration risk, as supported by a systematic review, which demonstrated similar incidences of regurgitation with the use of supraglottic airway devices with built-in gastric channel and endotracheal tube intubation [3]. These safety features of 2nd generation SGA result in increased bulk and stiffness of the airway tube which increases the vertical projection and encroach into the operating field, interfering with instrumentation during surgery. This might be especially so for cataract surgeries, where the surgeon may operate from the side of the patient (temporal approach phacoemulsification). For vitreoretinal and squint surgery, the surgeon usually approaches the surgical field from the head end; hence instrumentation is less likely to be hampered by the SGA. The addition of an angle connector or straight corrugated connector (subject to preference of the anaesthetist) between the airway device and the ventilator tubing helps to direct the airway tube caudally, away from the surgical field, however, connectors may also affect vertical heights. LMA ProSeal was identified as the best SGA with the lowest vertical projection amongst the 2nd generation SGAs and can be used if the 1st generation LMA Classic and Ambu AuraFlex are not available or when their use may not be appropriate. LMA Supreme, LMA AuraGain, LMA Protector and I-gel appear to be less than optimal.

This study has a few limitations. While insertion of SGAs in a manikin allowed standardisation of conditions for objective and quantitative measurements of vertical heights, the measurements may be subject to minor error. The vertical height and performance of each SGA also likely to vary with chosen SGA size and various patient’s characteristics (e.g. anatomy, obesity, dentition or the lack thereof, skeletal and soft tissue structures and anthropometry, etc.) in the clinical setting. We chose the commonly used SGA (size #4) in our institution and the repertoire is not exhaustive. The projected height is expected to be even higher with size #5 of the 2nd generation SGAs. Transferability of our findings into clinical practice is questionable as the use of a manikin may not fully imitate actual clinical conditions.

Conclusions

General anaesthesia is required in ophthalmic surgery in certain circumstances. Some clinicians may not be inclined to use the 1st generation SGA because of fear of gastric insufflation and subsequent risk of aspiration. Our manikin study has shown that among the 2nd generation SGAs, LMA ProSeal appears to have a more favourable vertical profile. We also describe a novel technique where 1st generation SGA may be used together with an orogastric tubes to mitigate aspiration risk in more prolonged ophthalmic surgeries. Our study is the first study comparing vertical heights of different 2nd generation SGAs in a standardised manikin. Custom-made or bespoke cradles may be considered to direct the SGA away from the surgical field. We recommend future studies to investigate the use of 2nd generation SGA in the clinical setting during ophthalmic surgery.

Author contributions

ES, JZ, JM and CMK have made substantial contribution to the manuscript in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Authors do not have any financial interest in the products included in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kumar CM, Eke T, Dodds C, Deane JS, El-Hindy N, Johnston RL, et al. Local anaesthesia for ophthalmic surgery—new guidelines from the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Eye (Lond) 2012;26:897–8. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly DJ, Farrell SM. Physiology and role of intraocular pressure in contemporary anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:1551–62. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brimacombe J. The advantages of the LMA over the tracheal tube or facemask: a meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:1017–23. doi: 10.1007/BF03011075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu SH, Beirne OR. Laryngeal mask airways have a lower risk of airway complications compared with endotracheal intubation: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2359–76. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holloway KB. Control of the eye during general anaesthesia for intraocular surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1980;52:671–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/52.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi GP, Inagaki Y, White PF, Taylor-Kennedy L, Wat LI, Gevirtz C, et al. Use of the laryngeal mask airway as an alternative to the tracheal tube during ambulatory anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:573–7. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199709000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qamarul Hoda M, Samad K, Ullah H. ProSeal versus Classic laryngeal mask airway (LMA) for positive pressure ventilation in adults undergoing elective surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD009026. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009026.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timmermann A, Bergner UA, Russo SG. Laryngeal mask airway indications: new frontiers for second-generation supraglottic airways. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28:717–26. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, et al. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:827–48. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]