Abstract

Not only did the 2015 Ebola Outbreak in West African countries leave the whole of the sub-Saharan region with a sense of uncertainty and panic, it was also a stress test to Africa’s and the wider world’s capacity to respond to and mitigate humanitarian crises in the twenty-first century. One plausible conclusion drawn from the spread and impact of the pandemic is that the pace of health infrastructure development in sub-Saharan Africa has lagged behind its population and economic growth posted in the last decade (2003–2013). An exhaustive audit of health infrastructure and remedial measures is, therefore, critical in navigating Africa to sustainable growth and development in the next decade. For the next charge of growth and development to not only be robust but also more sustainable and resilient to major emergencies (such as Ebola), there is a need to edify the state of healthcare across the continent to ensure the optimisation of the human resource and to redress the gap aggravated by loss of human-hours due to poor health.

Keywords: Africa, Health, Health Infrastructure, Economy, Ebola, Neoliberalism

Introduction

Good health remains one of the most crucial pillars of a functioning society; both as a measure of good social policy as well as the wellbeing of a population. This paper aims to provoke a rethink and a re-politicisation of the south-Saharan region’s low prioritisation of healthcare in the policy hierarchy by showing how low healthcare expenditure affects economic growth and people’s wellbeing. The paper seeks to show that the neoliberalised underinvestment in sub-Saharan Africa’s healthcare sector is a factor that threatens to derail the region’s capacity to unlock its long-term economic growth potential, thereby inhibiting sustainable economic growth. This provides a paradox within the neoliberal context, which mostly prioritises a “growing economy” ideology over the holistic wellbeing of people’s lives. We consider how the introduction of neoliberal policies in African states since the 1970s, through the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) enforced by the International Monetary Fund, have served to “deepen and entrench negative impacts on the determinants of health” (Garnham 2017, p. 668) and explore how the rise of neoliberalism has radically affected people’s experiences of engaging with the healthcare sector.

The paper is premised on Mushkin’s health-led growth hypothesis, which, in essence, argues that health in itself is a form of capital, and investment in healthcare can boost human capital, providing a catalytic effect to overall economic growth (Mushkin, 1962). Bhargava et al. (2001) also posit that it is important that the question interrogating the nexus between healthcare, well-being and economic growth, especially amongst low-income and politically fragile economies, be made more visible in policy and literature. The ideas in this paper are not necessarily nascent; instead, they are a build-up and an addition to Bedir’s (2016) paper which investigated the relationship between healthcare expenditure and economic growth in developing countries. Notwithstanding, our argument is distinct from Bedir’s paper in that it focuses on sub-Saharan Africa and uses time series data from the United Nations (UN) Development Agenda.

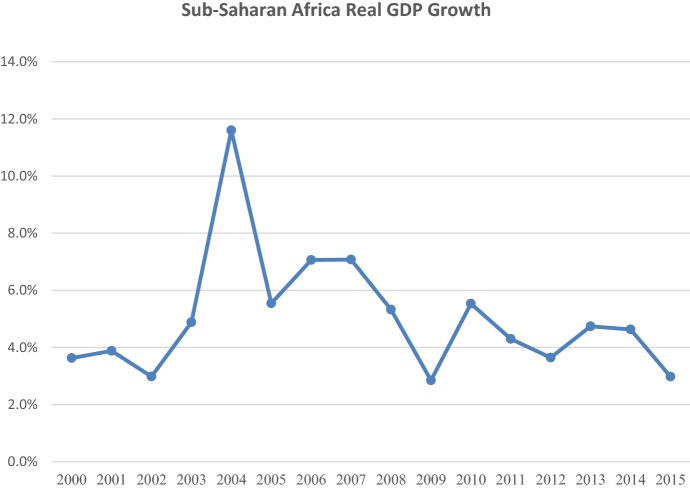

The UN (2012), through its System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda, stated that continued and sustained economic growth is not only a precondition for employment generation, but also provides countries the fiscal space to address other critical social concerns such as poverty, healthcare and education. It is, therefore, worrisome that sustainable, long-term economic growth remains elusive for most sub-Saharan African economies. The World Development Indicators show that despite posting relatively high gross domestic product (GDP) growth between 2000 and 2015, averaging 5% per annum (compared to 3.1% between 1990 and 2014), a major drawback to the region, is it’s capacity to create and sustain employment, a rise in household income and dignified standards of living.

Figure 1 shows the GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa over the last 15 years, which has been characterised by volatility—derailing the capacity for sustained high growth over long-term periods (at least 5 years).

Fig. 1.

Shows GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa over the last 15 years.

Source World Development Indicators

Health and the quest for sustainable growth

Securing sustainable growth is undeniably one of sub-Saharan Africa’s, and indeed the entire globe’s, most urgent needs of the twenty-first century. Over the last decade (2005–2015) the decelerating effect of a series of shocks on sub-Saharan Africa’s economic growth momentum has brought to light the region’s vulnerability. As an example, one of the major shake-ups of this decade, alongside the precipitous plunge in global commodity prices, has been the 2013–2015 Ebola outbreak, whose wreckage on the region’s economy includes an estimated $2.2 billion loss to the economies of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone (WHO 2015; World Bank 2015a, b, c). The impact of Ebola on the three countries could be costed to an aggregate of about 15.4% of their GDP at the time, and an estimated 8% decline in Liberia’s healthcare personnel due to infection (CDC 2016). The net effect of this health catastrophe has been twofold: on one hand, it has been indicative of the degree of unpreparedness of the region’s institutions to mitigate a crisis of the scale and nature of the Ebola outbreak. On the other hand, and more significantly, it has renewed interest in the role of investment in healthcare in driving economic growth in countries. In tabling the Health-Led Growth Hypothesis, Mushkin (1962) argues that the distinct benefit of investing in healthcare lies in the fact that health programs not only increase the quality of the labour force, but also the number of persons available in the labour market through increased wellbeing and a reduction in the number of deaths. Mushkin goes further to state that the number of workers that may be added through health programs is particularly large in non-industrial countries. This suggests that developing economies are poised to benefit more from investment in healthcare relative to their developed counterparts.

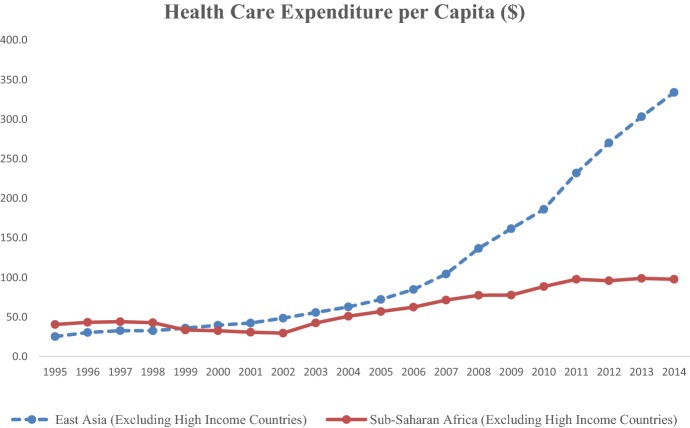

The Centre for Global Development (2009) has also stated that the worrisome trend of sub-Saharan Africa’s underinvestment in healthcare is worth considering and revising. To illustrate, between 1995 and 2015, sub-Saharan Africa’s healthcare expenditure (both public and private), as a percentage of the GDP, declined from 6.1 to 5.5%, whilst that of Southeast Asia and the Pacific increased from 1.6 to 3%, and that of South Asia increased from 3.8 to 4.3% (World Health Organization 2014). This indicates that whereas other regions have over time increased the proportion of national income designated for the health sector, sub-Saharan Africa has continued to register a decline. As shown in Fig. 2, in 1995, sub-Saharan Africa’s healthcare expenditure per capita stood at $40.5, compared to $25.5 for Southeast Asia and the Pacific; by 2014, the two regions’ healthcare expenditures per capita stood at $97.6 and $333.9, respectively. This shows that in terms of growth (compounded annual growth rate), Southeast Asia and the Pacific’s expenditure between 1995 and 2014 grew by 14.6%, compared to 4.7% for sub-Saharan Africa. It therefore comes as no surprise that whereas sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 24% of the global disease burden, it accounts for a paltry less-than-one-percent of the world’s health expenditure (World Bank 2008), painting a dire picture of the healthcare funding gap bedevilling the region.

Fig. 2.

Shows the evolution in healthcare expenditure per capita between sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia.

Source World Development Indicators

Figure 2 shows the evolution in healthcare expenditure per capita between sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia, revealing that whereas the two regions were on par in 1995, by 2014 Southeast Asia posted healthcare expenditure three times as high as sub-Saharan Africa’s.

The neoliberalisation of healthcare in the sub-Sahara

Since the late 1980s, the sub-Sahara has been struggling to address the issues of inequality that have been inflated by neoliberal policies and capitalist development policies that focus on production of labour and little on the health and wellbeing of the “producers” of the said labour. Globally, the rolling out of neoliberal policies has led to a plethora of harmful socioeconomic consequences, including increased poverty, unemployment, and deterioration of income distribution (Rotarou and Sakellariou 2017; Collins et al. 2015). Hartmann (2016, p. 2145) states that “neoliberalism typically refers to minimal government intervention, laissez-faire market policies, and individualism over collectivism [which] has been adopted by—and pressed upon—the majority of national governments and global development institution.” She further states that “neoliberal policies have contributed to the privatization and individualization of healthcare, resulting in growing health inequalities.” By privatising healthcare, education, electricity, water and housing, neoliberals argue that private institutions are more capable, effective and efficient in providing social services. Harvey (2007) states that neoliberalism is “a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, … free trade” and a “hands-off” approach from the government. This is what Friedman referred to as the system of “free market capitalism” (Friedman 2009). However, (Garnham (2017) argues that decreasing public spending and government involvement in the welfare of people through the rhetoric of choice and freedom has a harmful impact on people’s health and wellbeing.

The biggest conceptual challenge is that neoliberal ideology adopts the language of freedom and choice, increased foreign investments, and open markets and trade to progress policies that lead to privatisation of basic needs such as education, healthcare, water, electricity and housing. The rich can often afford these services and can compete “fairly” in the “free market”, but the poor—unable to afford health care, education or decent housing—are left marginalised. Njoya (2017) explored the use of language in promoting inequality in the healthcare system. She argued that “neoliberalism uses the language of social policy and justice but [insidiously] drives a very corporate and unequal agenda.”

Neoliberalism has radically shifted the African public health space in the last two decades. Most sub-Saharan African countries drastically reduced their healthcare budgets following the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Structural Adjustment programs (SAPs) directives. As Hartmann (2016, p. 2146) wrote, it “decentralized health care decision-making and funding, resulting in wide-scale privatization of health care services, delivery, and insurance, which led to structural segmentation and fragmentation.” SAPs have had myriad negative impacts on African economies, including, but not limited to, “inflationary pressures, the marginalization of the poor in the distribution of educational and health benefits and a reduction in employment” (Rono 2002, p. 84). As the main impetus of the SAPs was to reduce and ration expenditure, structural adjustment in the healthcare sector slashed public spending on primary healthcare, and aided the privatisation of health systems and services. In Kenya, for example, The Bamako Initiative of 1987 anchored cost-sharing as a central tenet of public health policy, in which patients were required to pay for nearly all costs of diagnosis and treatment (Rono 2002). Outside of an emergency, patients were required to provide proof of payment before medical services are availed. By channelling funding to narrow medical interests, structural adjustment policies resulted in an uneven medical landscape, with a few prestigious fields surrounded by poorly resourced departments. Clinicians had to tailor their decisions about treatment to the limited medicine, technologies and resources available.

The increased number of private healthcare organisations, coupled with a significant reduction in the role of government in the provision of healthcare services, contributed to extensive negative outcomes on the quality, effectiveness, cost and access of health systems and services, which severely impacted on people’s wellbeing. Rotarou and Sakellariou (2017, p. 497) state that the private institutions, “with their focus on increasing profits, and not on providing affordable and good-quality healthcare, have led to the deterioration of public health systems, increase in urban–rural divide, as well as increase in inequality of access to healthcare services.” Privatisation of healthcare has made services more unaffordable and less available to the population of people that need it the most. As a result, life expectancy has stagnated or fallen in most African countries, and mortality from preventable infections and diseases continues to rise. Further to this, the politics of healthcare through a neoliberal lens are often framed as “individual” issues rather than “structural and ideological” issues. This implies that the neoliberal approach to health has diminished the idea of healthcare as a universal human right.

Reframing, reshaping, rethinking and re-politicising healthcare reveals the colonial attitudes that dictate who “deserves” good healthcare. Njoya (2017) states,

[Politicians in Kenya] come to the rescue of the poor by paying hospital bills but will not have a conversation about the fact that we the taxpayers are paying millions [worth of] medical cover for each of them and will not engage in a conversation about the underfunding of healthcare, and the looting of the little money given to healthcare. When [the] Netherlands and the UN are helping foreign companies purchase Kenyan hospitals, [they are] supporting our government’s deafness to [our right to basic healthcare] and [promoting their] refusal to fund public hospitals.

The privatisation and buying out of African hospitals by foreign companies in an attempt to “help and rescue them” is a capitalist response that undercuts universal healthcare for Africans by appropriating the language of care and inclusion. In reality, this “white saviour approach” is layered with nothing but racism, disempowerment, exploitation of people, and exclusion of those who cannot afford those “privatised” services. Access to health services, therefore, remains both a political as well as a human rights issue that’s closely tied to social justice (Braveman and Gruskin 2003b); but Africa’s colonial history, fuelled by Western greed for her resources, promotes discriminatory policies that continue to impact Africans and their wellbeing.

Therefore, to understand the implications of neoliberalism on healthcare systems in sub-Saharan Africa, we must first probe the historical context of its volatile political, economic, social and colonial history. The continent, decades after the end of “official” British rule, is still trapped in poverty with extreme issues of political conflict and inequality. The colonial system sowed seeds of dependency and low self esteem, conflict and suspicion, greed and individualism, which have made the continent a prime target for neo-colonialism as well as exploitative economic policies guised as freedom of choice, free market and trade (Hilary 2010). Braveman and Gruskin (2003a) argue that “there is an absence of systematic [policies that foster equity rather than just equality]…between groups with different levels of underlying social advantage/disadvantage”. This means that “socially disadvantaged groups [who statistically] have higher medical needs receive less healthcare and support” (Baker 2010). In fact, a study by Chuma et al. (2012) showed that hospital services in Kenya remain pro-rich and anti-poor. The study showed that there is a significant shift towards privatising healthcare in Kenya, and accessibility to good healthcare is mostly determined by people’s financial capability—which raises more concerns about how the public health system perpetuates social inequality. Chuma et al.’s (2012) study highlights the effects and danger of the “free-market and trading” concepts and policies promoted by the neoliberal ideology, and shows its capacity to marginalise those who are not able to be competitive in the “free market”. The irony of the terminology is therefore lost in its definition. They state that the “poorest population is in greater need of health services than the richest population, and should therefore receive the largest share of health system benefits. … [However, research] confirms that the poorest Kenyans [with the greatest] health needs, receive the least share of total health system benefits.”

This means that the high costs of private healthcare promote significant disparities. In fact, in the last two decades neoliberalism has minimised the important aspect of the social determinants of health due to its singular concern with the medical, individualised and curative healthcare practices. Overemphasis on biomedical and specialised curative practices tend to ignore the social, cultural and political environments that contribute to wellbeing (or lack thereof) of people. Rotarou and Sakellariou (2017) conclude that,

While it is argued that a well-functioning health system aims at: (1) improving the health of individuals, families, and communities; (2) defending the population against threats to its health; (3) protecting individuals against the financial costs of bad health; (4) providing equitable access to care that has people at its centre; and (5) enabling people to participate in decisions that affect their health and health system, neoliberalism does not share the same goals. It can be argued that neoliberal practices in the field of health, especially with regards to points three and four, go exactly in the opposite direction.

A holistic approach to health for the African populace, therefore, is one that considers how Africans’ overall health links to their social, cultural, political and economic environments. This means that health care must be contextual. Contextuality means that healthcare responses should first and foremost understand people’s underpinning ethos and philosophies of life, and how cultural, political, social and economic contexts shape “attitudes, values, customs, and rituals” that inform healthcare decicion making (De la Porte 2016, p. 1). Contextuality in health appreciates the embodied burden of living in a continent that has been rubbished and marginalised for years through the Eurocentric global order. Africans’ health outcomes are therefore deeply entrenched in systems under which they live, but neoliberal policies do not encourage abstract thinking about health problems; instead, neoliberalism frames healthcare (or lack thereof) as an individual rather than as a social or political or economic issue. The irony is that as people get sicker, they become less productive and less useful to the neoliberal ideology of maximising profits through the use of people’s bodies.

Implications of poor health infrastructure on African economies

Curative as well as preventative aspects of African healthcare systems play a significant role in the health dynamics of the sub-Saharan population, which in turn unleash unintended impacts on African economies. When weighing the infrastructural aspects of the healthcare sector, it is important to determine the extent to which the local populace depends on these health systems, and the extent to which this becomes a factor in the economic productivity of the said economies—primarily through labour participation. The World Health Organization (2016) report for deaths per 100,000 people in sub-Saharan Africa places HIV as the most common cause, followed by waterborne diseases, then malaria, ischemic heart disease and meningitis. This mortality prevalence through illnesses and diseases demonstrates a dearth of medical intervention, where with prompt and quality care, many of these causes can be overcome. Unfortunately, more often than not, people who need this medical intervention are ignored. This “loss” has a profoundly negative impact on economic productivity. See also Jamison et al. (2006); Lopez et al. (2006).

The estimates for the burden of diseases on those who survive are weighted in disability-adjusted life years (DALY); and the attendant opportunity costs as well as the loss of income per million people is approximately twice that of OECD countries (Lvovsky 2001). This productivity loss reflects not just individual incidences of institutional failure of the health infrastructure multiplied by the frequency of occurrence of these illnesses among the populace, but also in the subsequent negative attitudes developed by the patients towards seeking physician-assisted care and curative interventions (after frustrating encounters with these dismal health infrastructures).

The existing literature on the impact of health infrastructure on economies takes on slightly divergent perspectives whilst driving towards a common (though broad) goal. Some literature (for example, Bhargava et al. 2001; Wheeler 1980; Agénor 2008; Hosoya 2014; Knowles and Owen 1995) takes an endogenous growth model to illustrate the effect of health and access to health infrastructure on cross-national deviations in economic growth and average income levels. On the other hand, Gallup and Sachs (2001), as well as McCarthy et al. (2000), focus on the cost of diseases, like malaria, on economic growth rates. As the World Health Organization claims, the comparatively lower levels of health infrastructure development coincide with high disease burden, which affects economic development through depressing four principal economic activities: domestic tourism, foreign tourism, land utilisation, and the internal mobility of labour (both in quantity and quality).

In the same vein, in the nature of many African communities—primarily the rural population, but also increasingly semi-urban areas—the biggest burden of loss of labour hours and quality due to low access to health infrastructure is centred on four main industries; namely agriculture, tourism, mining and manufacturing. The burden on these key sectors produces a direct impact on import–export balance as well as the balance of payment as a factor of GDP. A proper appraisal of the impact of health infrastructure on African economies is most poignantly reflected in the drastically contrasting economic growth of the sub-Saharan state vis-à-vis its huge natural resource endowment.

Unlike the other underdeveloped continents and subcontinents, in Africa, and especially the sub-Saharan countries, there is still a major challenge when it comes to accessing basic and essential human needs—chief among them proper healthcare systems. A case in point is Kenya, which is one of the richest sub-Saharan states yet has a mortality rate of 48% (under 12 months old) and a life expectancy that stands at 58 years (WHO 2015). This life expectancy is 10% lower than the global average; a challenge attributed to communicable diseases mostly for persons over the age of 42 years (UNICEF 2015). To further illustrate this, an estimated 82% of health loss and the resultant economic labour loss is occasioned to treatable communicable diseases, where access to health infrastructure has not improved (WHO 2010). These numbers, relative to the entire population, point to a prevalence of loss of considerable labour hours due to comparatively high incidence of easily treatable diseases and conditions—reflecting significant problems in the healthcare sector for which both the government and the private sector need to consolidate their efforts in addressing.

The reliance on poor infrastructure also feeds into five other major pre-existing economic and economic-related challenges, such as poverty, unemployment, climate change, border and ethnic conflicts, and under-industrialisation, in ways that make prioritising healthcare a challenge. This self-reinforcing tapestry of challenges affects healthcare infrastructure in ways that lead to a third problem: neoliberalism and the correlation between health infrastructure and donor support, with their increasing push for privatisation of healthcare services. As discussed before, in most low-income sub-Saharan states most of the healthcare infrastructure is provided or complimented by the private sector. The inevitable outcome—which includes increasing privatisation of healthcare—covers the entire scope of the healthcare sector, including laboratories, wards, staffers, pharmacies and theatres, and even research funding. The underfunding and the understaffing of the poor public health sector pushes most patients to the private sector with higher healthcare costs—compared to public healthcare—and in turn lowers family savings and disposable incomes for the affected and or infected families.

Meanwhile, over-reliance on donor support, especially on such a vital national sector as healthcare, constitutes a critical yet risky boost to national health infrastructure, especially given the possibility of shock doctrine as a means of diplomatic coercion (Klein 2007). Poor health infrastructure, and the resultant influence of donor support, therefore becomes a geopolitical risk factor predisposing sub-Saharan states to vendor-driven projects (that work in favour of donor states and organisations). The covert as well as overt implication is the pressure on how the funded nations interact with international norms, powerful countries and regional bodies. This particular influence has a negative impact on how poor countries negotiate trade deals with the donor countries, as well as how they vote on issues of national and regional importance.

A mostly negative implication of poor health infrastructure on African economies is that the poor and often inadequate infrastructure necessitates medical tourism. The global medical tourism is a billion-dollar industry involving millions of patients travelling each year to other countries to seek medical treatment (Fetscherin and Stephano 2016; Lunt et al. 2016). Medical tourism has no clear definitions, but it generally refers to the practice of patients leaving their primary residence to travel across the nation or national borders with the core purpose of seeking access to medical treatment and care (Carrera and Bridges 2006; Crooks and Snyder 2011). Medical tourism, often arising due to poor public health infrastructure, not only leads to cash outflows from developing economies, over the long term it also undermines the initiative to build local health systems to cater for those who cannot afford to fly abroad for medication or treatment. Africa’s medical tourism is estimated at $1 billion by World Bank (2015a, b, c) statistics. Technically, the limited existence of essential medical technology as part of health infrastructure causes ripple effects in the local treatments (Gupte and Panjamapirom 2014). Ironically, poor health infrastructure leads to costly charges and medical care that is delayed due to long waiting lists, overworked staffers and inadequate service quality, which in turn push patients to consider medical tourism (Beladi et al. 2015; Fisher and Sood 2014). Given that the majority of African medical tourists seek treatment for chronic diseases, as opposed to cosmetic procedures, this demonstrates the dire need for extra budget allocation and investment in basic health infrastructure across the sub-Saharan region.

The costliest impact of poor health infrastructure focuses on the brain drain occasioned by limited opportunity for medics, and the sub-par working conditions within the limited health infrastructure systems available in the continent (Beladi et al. 2015; Naicker et al. 2009; Eastwood et al. 2005; Oberoi and Lin 2006; Pang et al. 2002; Kirigia et al. 2006). “Brain drain” loosely refers to the emigration of highly qualified professionals to other countries for “greener pastures” (Clemens and Pettersson 2008; Ntshebe 2010). Every year, thousands of doctors and nurses leave the continent in search of better working environments and remuneration. Mills et al. (2011) estimated the loss of returns from this mass emigration of doctors from the nine African Countries they studied to be about $2.17 billion. With 57 countries, Africa suffers from a critical shortage of healthcare workers, documenting a deficit of 2.4 million doctors and nurses (Naicker et al. 2009; Adeyemi et al. 2018). With 2.3 healthcare workers per 1000 people in Africa, African doctors and nurses are overworked, underfunded and overwhelmed (Ntshebe 2010). This is compounded by the fact that, even though Africa carries the biggest portion of the global disease burden while only accounting for 16% of the global population (Roser and Ritchie 2018), it only spends 1% of Total Healthcare Expenditure (THE) on healthcare.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the cost of training a single medic from lower school to university averages about $US65,997; yet a majority of these end up emigrating abroad. This emigration is largely based on a number of pull factors in the destination country and push factors in their resident sub-Saharan nations (Kirigia et al. 2006). The institutional disintegration, mismanagement and general limitations of sub-Saharan health systems predisposes the medical professionals to certain push factors that fuel this brain drain, including but not limited to weak health systems, workplace violence, lower remunerations, unclear career paths, lack of protective gear, and nepotism in workplace recruitment and promotion (Oyelere 2007; Renzaho 2007; Soucat 2013). The result is not just a loss of medical labour, but also the foregone benefits including potential improvement in health sector. It is also a loss to the potential medical research that could be undertaken by the professionals who may otherwise have opted to stay.

Discussion

As discussed in this paper, Africa’s demographic transition and the tilting of scales from potential disaster to a dignified future depends significantly on a population that is both healthier and better educated (Canning et al. 2015). In the recent past, two factors seem to be colluding to present a fresh and augmented impediment to the realisation of a healthier population in the continent. One, the general slowdown in the growth of healthcare expenditure per capita to an average of 4.9% per annum between 2010 and 2015, compared to 10.8% between 2004 and 2009, is cause for concern. According to the World Health Organization (2015), only five African countries (Zambia, Rwanda, Togo, Madagascar and Botswana) have realised the Abuja Declaration target of designating 15% the aggregate public expenditure to the health sector; this is indicative of the resource constraints that bedevil the health sector. Two, the increasingly inward-looking policy stance by the USA under President Donald Trump presents a new challenge to Africa. In its maiden budget, the Trump administration proposed a 21% slash in foreign aid, year-on-year, to USD 17.9 billion in 2018, and this threatens to create ripple effects throughout Africa. Kenya is Sub-Sahara’s largest recipient of USA foreign aid, for instance, having received USD 823.8 million in 2015 (Concern Worldwide-US, 2018). Of this amount, 57.4% was directed to population policy, reproductive health and basic health, signalling the vulnerability the health sector faces in light of the change in policy stance by the USA—given that donor funding as a percentage of the aggregate health sector’s budget rose from 8% in 1994/1995 to 16% by 2001/2002 (Wamai 2009).

In this paper, however, following Moyo’s (2009) argument, we do not advocate for foreign aid as a solution to Africa’s healthcare problems. We see home-grown solutions in select countries offering a glimmer of hope for the future of sustainable intervention healthcare in Africa. In Ethiopia, for instance, the Development Bank of Ethiopia has undertaken to extend tax-free loans (with a ceiling of 70% of new investment) for new investment in the production of pharmaceutical products by local firms. This implies that local firms producing pharmaceutical products now have to invest only 30% of the required capital at the project’s inception, presenting much needed relief to local firms aiming to scale up production capabilities. Kenya’s eHealth Strategy 2011–2017, which is a set of interventions anchored principally on emerging trends within the information communication technology space, is doing a great deal to mitigate infrastructural and personnel constraints on delivery of healthcare services. Anchored on mobile health and telemedicine, the strategy is well-positioned to tap into the vast resource that is Kenya’s high technology engagement. This rate of cell phone ownership and technology literacy can be used to address gaps in dissemination of medical services.

The eLearning program between the Nursing Council of Kenya and the African Medical Research Foundation, through which community health nurses are trained and certified, is equally a game changer in the quest to meet the shortage of qualified medical personnel in the remote parts of the country (Nguku 2009). These emerging trends in healthcare solutions bode well for a continent grappling with resource constrains in meeting healthcare challenges, and suggest that involvement by both state and non-state actors provides the best hope for a sustainable approach.

Concluding comments

This paper has considered arguments that show the burden of poor health on African economies. We have argued that a healthy workforce facilitates sustainable growth and development in sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed, by drawing from Mushkin theory of human capital we have elucidated how a healthy population is a measurement for social and economic development. A comparison of healthcare expenditure per capita between Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa reveals that whereas the two regions were nearly on par in 1995 for healthcare expenditure, today the former spends three times as much as the latter in this area; a fact that manifests in the overall socioeconomic disparity between the two regions. Many arguments in the literature state that poverty causes poor health. While this is true in most instances, we also add that poor health can also lead to poverty, and can be used as a theoretical and conceptual framework to explain some of the underdevelopment in Africa.

Another major argument that we explored is the impact that poor healthcare infrastructure systems have had on labour—especially the non-renewable productive hours lost to disease prevalence. Poor healthcare infrastructure, when factored as a national security issue, exposes the vulnerability of nation-states to manipulation through the donor funding provided to bridge the funding gap in their respective healthcare sectors. In the longer term, the resultant brain drain following frustrations of the local medical professionals—due to inadequate public infrastructure—disincentivises the development of local healthcare systems while fomenting healthcare systems abroad, which further exacerbates medical tourism and the resultant cash outflows from sub-Saharan states.

We have shown how patients, burdened by a commercialised healthcare system, prioritise treatment over diagnosis and prescriptive medical procedures and measures. They in turn seek medical intervention when otherwise simple ailments have morphed into chronic illnesses, costing them more and having a greater impact on their bodily health. There is also the psychological and mental impact of weakening social welfare systems in the society, and commercialisation of basic social services. Data gaps in mental health statistics, however, make it hard to compute the impact of mass retrenchment, privatisation and rising costs of living on people’s mental health—and the long-term effects it unleashes on societal systems and norms.

We have argued that, simply, inadequate funding of healthcare services by the government has a number of adverse impacts on households: increasing the burdensome out-of-pocket expenditure by individuals when accessing medical care. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure payments made directly by persons seeking healthcare services either as pre-payment or co-payment, alongside insurance for accessing services, consist of a huge proportion of aggregate healthcare expenditure in sub-Saharan economies, as evidenced by Leive and Xu (2008). This pushes people who are already poor, or surviving paycheck to paycheck, into the brink of extreme poverty, and may significantly impact healthcare-seeking decisions.

Finally, we have also considered how neoliberal ideology continues to impact the wellbeing of Africans in terms of their accessibility to good health and care. The premise of the paper has been to conceptually explore the question, “Can Africans and their economies thrive when the majority of its populace is either sickly or will be sick in the future and cannot access adequate healthcare?” The answer is No.

Biographies

Dr Kathomi Gatwiri

is a lecturer based at Southern Cross University where she teaches Social Work & Social Policy. She is a social worker and psychotherapist whose research interest focus on trauma, race and African womanhood.

Julians Amboko

is a finance and economics correspondent with the Nation Media Group based in Nairobi, Kenya. He spent five years covering sub-Saharan focused macro and microeconomic research with StratLink Africa, where he covered a portfolio of ten economies including Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Ethiopia, Zambia and Tanzania. Julians has published widely with the London School of Economics Business Review, the International Growth Centre, the World Economic Forum and Next Billion focusing on thematic issues regarding economic policy in Africa including regional integration, foreign exchange volatility and impact finance.

Darius Okolla

is a Content Strategist at Archon Capital, a digital content creation firm in Nairobi, a novelist, and a journalist at lifestyle magazine, Nairobicool.com. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce - Finance degree, from Kenyatta University.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adeyemi RA, Joel A, Ebenezer JT, Attah EY. The effect of brain drain on the economic development of developing ccountries: evidence from selected African countries. Journal of Health and Social Issues. 2018;7(2):66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Agénor P-R. Health and infrastructure in a model of endogenous growth. Journal of Macroeconomics. 2008;30(4):1407–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.jmacro.2008.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PA. From apartheid to neoliberalism: health equity in post-apartheid South Africa. International Journal of Health Services. 2010;40(1):79–95. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.1.e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedir S. Healthcare expenditure and economic growth in developing countries. Advances in Economics and Business. 2016;4(2):76–86. doi: 10.13189/aeb.2016.040202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beladi H, Chao C-C, Ee MS, Hollas D. Medical tourism and health worker migration in developing countries. Economic Modelling. 2015;46:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2014.12.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava A, Jamison DT, Lau LJ, Murray CJL. Modeling the effects of health on economic growth. Journal of Health Economics. 2001;20(3):423–440. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00073-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57(4):254–258. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Gruskin S. Poverty, equity, human rights and health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2003;81(7):539–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning D, Raja S, Yazbeck AS. Africa’s demographic transition: Dividend or disaster? Washington, DC: World Bank Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera PM, Bridges JFP. Globalization and healthcare: Understanding health and medical tourism. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 2006;6(4):447–454. doi: 10.1586/14737167.6.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. 2016. Cost of the Ebola Epidemic [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/cost-of-ebola.html.

- Centre for Global Development. 2009. Partnerships with the Private Sector in Health: What the International Community Can Do to Strengthen Health Systems in Developing Countries. Retrieved from https://www.cgdev.org/files/1423350_file_CGD_PSAF_Report_web.pdf.

- Chuma J, Maina T, Ataguba J. Does the distribution of health care benefits in Kenya meet the principles of universal coverage? BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens MA, Pettersson G. New data on African health professionals abroad. Human Resources for Health. 2008;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colins C, McCartney G, Garnharm L. Neoliberalism and health inequalities. In: Smith KE, Bambra C, Hill SE, editors. Health Inequalities: Critical Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 124–137. [Google Scholar]

- Concern WorldWide-US. 2018. Foreign Aid by Country: Who is getting the most and how much. Retrieved from https://www.concernusa.org/story/foreign-aid-by-country-getting-how-much/.

- Crooks VA, Snyder J. Medical tourism. Canadian Family Physician. 2011;57(5):527–529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Porte A. Spirituality and healthcare: Towards holistic peoplecentred healthcare in South Africa. African Journals Online. 2016;72(4):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood JB, Conroy RE, Naicker S, West PA, Tutt RC, Plange-Rhule J. Loss of health professionals from sub-Saharan Africa: the pivotal role of the UK. The Lancet. 2005;365(9474):1893–1900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66623-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetscherin M, Stephano R-M. The medical tourism index: Scale development and validation. Tourism Management. 2016;52:539–556. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C, Sood K. What is driving the growth in medical tourism? Health Marketing Quarterly. 2014;31(3):246–262. doi: 10.1080/07359683.2014.936293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. Capitalism and freedom. London: University of Chicago press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup JL, Sachs JD. The economic burden of malaria. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2001;64(1):85–96. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnham LM. Public health implications of 4 decades of neoliberal policy: A qualitative case study from post-industrial west central Scotland. Journal of Public Health. 2017;39(4):668–677. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdx098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupte G, Panjamapirom A. Understanding Medical Tourism. In: Culyer AJ, editor. Encyclopedia of Health Economics. San Diego: Elsevier; 2014. pp. 404–410. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann C. Postneoliberal public health care reforms: Neoliberalism, social medicine, and persistent health inequalities in Latin America. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(12):2145–2151. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hilary J. Africa: Dead Aid and the return of neoliberalism. Race & Class. 2010;52(2):79–84. doi: 10.1177/0306396810377010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya K. Public health infrastructure and growth: Ways to improve the inferior equilibrium under multiple equilibria. Research in Economics. 2014;68(3):194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.rie.2014.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Musgrove P. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirigia JM, Gbary AR, Muthuri LK, Nyoni J, Seddoh A. The cost of health professionals’ brain drain in Kenya. BMC Health Services Research. 2006;6(1):89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein N. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Macmillan; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles S, Owen PD. Health capital and cross-country variation in income per capita in the Mankiw-Romer-Weil model. Economics Letters. 1995;48(1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/0165-1765(94)00577-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leive A, Xu KJ. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86:849–856. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: Systematic analysis of population health data. The Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunt N, Horsfall D, Hanefeld J. Medical tourism: A snapshot of evidence on treatment abroad. Maturitas. 2016;88:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lvovsky, K. 2001. Environment Strategy Papers No. 1: Health and Environment. World Bank, October.

- McCarthy, D., H. Wolf, and Y. Wu. 2000. The Growth Costs of Malaria. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w7541.

- Mills EJ, Kanters S, Hagopian A, Bansback N, Nachega J, Alberton M, Au-Yeung CG, Mtambo A, Bourgeault IL, Luboga S, Hogg RS, Ford N. The financial cost of doctors emigrating from sub-Saharan Africa: Human capital analysis. BMJ. 2011;343:d7031. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyo D. Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is a Better Way for Africa. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mushkin SJ. Health as an investment. Journal of Political Economy. 1962;70(5, Part 2):129–157. doi: 10.1086/258730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naicker S, Plange-Rhule J, Tutt RC, Eastwood JB. Shortage of healthcare workers in developing countries–Africa. Ethnicity and Disease. 2009;19(1):60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguku, A. 2009. Nursing the Future: e-Learning and clinical care, in Kenya. Retrieved from London. https://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/newsite/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/PV-Nursing-the-Future.pdf.

- Ntshebe O. Sub-Saharan Africa’s brain drain of medical doctors to the United States: An exploratory study. Journal of Insight on Africa. 2010;2(2):103–111. doi: 10.1177/0975087814411123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Njoya, W. 2017. Time for Neoliberalism Lesson Number 4. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/wandia.njoya.

- Oberoi SS, Lin V. Brain drain of doctors from southern Africa: Brain gain for Australia. Australian Health Review. 2006;30(1):25–33. doi: 10.1071/AH060025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyelere RU. Brain drain, waste or gain? What we know about the Kenyan case. Journal of Global Initiatives. 2007;2(2):113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Pang T, Lansang MA, Haines A. Brain drain and health professionals: A global problem needs global solutions. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2002;324(7336):499. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7336.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzaho, A. 2007. Unpacking the brain drain in Sub-Sahara Africa through public health lenses: Implications for development aid. Measuring Effectiveness in Humanitarian and Development Aid: Conceptual Frameworks, Principles and Practice, 279–299.

- Rono K. The impact of the structural adjustment programmes on Kenyan society. Journal of Social Development in Africa. 2002;17(1):81–98. doi: 10.4314/jsda.v17i1.23847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roser, M., and Ritchie, H. 2018. Burden of Disease. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/burden-of-disease.

- Rotarou ES, Sakellariou D. Neoliberal reforms in health systems and the construction of long-lasting inequalities in health care: A case study from Chile. Health Policy. 2017;121(5):495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucat A. The labor market for health workers in Africa: a new look at the crisis. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2012. UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/843taskteam.pdf.

- UNICEF (2015) Statistics: A focus on Kenya [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/kenya_statistics.html.

- Wamai R. The health system in Kenya: Analysis of the situation and enduring challenges. Japan Medical Association Journal. 2009;52(2):134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler D. Basic needs fulfillment and economic growth: A simultaneous model. Journal of Development Economics. 1980;7(4):435–451. doi: 10.1016/0304-3878(80)90038-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World health statistics 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2014. WHO Global Health Expenditure Atlas. Retrieved from Switzerland. https://www.who.int/health-accounts/atlas2014.pdf.

- WHO. 2015. Ebola Situation Report. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/192654/1/ebolasitrep_4Nov2015_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- WHO . World Health Statistics 2016: Monitoring Health for the SDGs Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2008. The Business of Health in Africa: Partnering with the Private Sector to Improve People’s Lives. [Press release]. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/878891468002994639/pdf/441430WP0ENGLI1an10110200801PUBLIC1.pdf.

- World Bank. 2015a. Summary on the Ebola Recovery Plan: Guinea [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/ebola/brief/summary-on-the-ebola-recovery-plan-guinea.

- World Bank. 2015b. Summary on the Ebola Recovery Plan: Liberia—Economic Stabilization and Recovery Plan (ESRP) [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/ebola/brief/summary-on-the-ebola-recovery-plan-liberia-economic-stabilization-and-recovery-plan-esrp.

- World Bank. 2015c. Summary on the Ebola Recovery Plan: Sierra Leone [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/ebola/brief/summary-on-the-ebola-recovery-plan-sierra-leone.