Abstract

As feared and deadly human diseases globally, Rabies virus contrived mechanisms to escape early immune recognition via suppression of the interferon response. This study, preliminarily investigated whether Rabies virus employs epigenetic mechanism for the suppression of the interferon using the Challenge virus standard (CVS) strain and Nigerian street Rabies virus (SRV) strain. Mice were challenged with Rabies virus (RABV) infection, and presence of RABV antigen was assessed by direct fluorescent antibody test (DFAT). A real time quantitative Polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was used to measure the expression of type II interferon gamma (IFNG) and methylation specific quantitative PCR for methylation analysis of 1FNG promoter region. Accordingly, DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) and histone acetyltransferase (HAT) enzymes activities were determined. RABV antigen was detected in all infected samples. A statistically significant increase (p < 0.05) in mRNA level of IFNG was observed at the onset of the disease and a decrease as the disease progressed. An increase in methylation in the test groups from the control group was observed, with a fluctuation in methylation as the disease progressed. DNMT and HAT activities also agree with methylation as there was an observed increase activity in test group compared with control group. Similar fluctuation pattern was observed in both CVS and SRV groups as the disease progressed with HAT, being the most active proportionally. This study suggests that epigenetic modification via DNA methylation and histone acetylation may have played a role in the expression of type II interferon gamma in Rabies virus infection.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Rabies virus infection, Interferon gamma, Methylation, DNA methyltransferase, Histone acetyltransferase

Introduction

Rabies is regarded as one of the oldest known and most feared human disease recognized since the early length of civilization (Getachew et al. 2014). According to WHO, rabies poses a threat to more than 3 billion people around the globe with over 59,000 and 21,476 deaths recorded worldwide and in Africa respectively (World Health Organization (WHO) 2018). Rabies virus (RABV) belongs to the genus Lyssavirus, family Rhabdoviridae, it is a widespread zoonotic disease caused by neurotropic viruses and is most commonly spread by the bite of a rabid animal (Silva et al. 2013). The RNA genome of the virus encodes five proteins in a highly conserved order, and they code for: nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), glycoprotein (G), and a viral RNA polymerase (L) (Yousaf et al. 2012). In most mammalian species, RABV is known to cause fatal encephalomyelitis with little or no histopathological evidence of neural destruction in animals dying of rabies (Sugiura et al. 2011). RABV exploits the nervous system (NS) network and predominantly infects the neurons to ensure its progression from the entry site to the exit site (Chopy et al. 2011). Fever, bodily discomfort, general weakness, headache are symptoms of rabies in humans. As disease progresses, abnormal behavior, delirium, insomnia, hallucinations, and respiratory failure may occur (Burgos-Cáceres 2011a, b). The disease is often fatal once symptoms develop and it remains one of the most ancient and deadly of human infectious diseases (Burgos-Cáceres 2011a, b).

Despite extensive investigation in the past 10 decades, rabies remains a public health threat globally due to uncontrolled enzootic rabies, poor access to vaccines, and poor information on the risk of contracting rabies after animal exposure (Yousaf et al. 2012). In Nigeria, a canine RABV was isolated from a trade dog recently, and it was discovered that its complete genome sequence has a high degree of homology to the canine RABV circulating in Africa (Zhou et al. 2013; Kia et al. 2018). Similarly, molecular characterization of the whole genome of RABV was conducted on trade dogs in Plateau State, Nigeria, which provides insight to improved understanding of the pathogenesis, molecular epidemiology, and rabies control in Nigeria (Kia et al. 2018). The pathogenic RABV has evolved specific mechanisms to evade early immune recognition by the immune system and avoid premature death of infected neurons. The increase in interferon response at the onset of rabies virus infection followed by a decrease in its production as disease progresses has been implicated in several studies (Ito et al. 2010; Srithayakumar et al. 2014). For successful establishment of infection, viral IFN-antagonistic mechanisms therefore play pivotal roles (Brzózka et al. 2005), which may provide a viable strategy in combating and/or managing the disease. It has also become apparent that fundamental in the interplay between host cells and viruses are epigenetic changes (Galvan et al. 2015).

Interferons (IFN) are naturally occurring proteins secreted by diverse cells such as fibroblasts, natural killer cells, white blood cells, and epithelial cells in response to pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, tumour and cancer cells, and other foreign substances (Haji Abdolvahab et al. 2016). IFN discovery was originally as a result of its ability to “interfere” with virus infection (Barkhouse et al. 2015). Interferon Gamma (IFN훾), a biologically active 34 kDa homodimer is secreted primarily by natural killer (NK) cells, T helper1 (TH1) CD8+ T-cells and CD4+ T-cells. IFN훾 mediates a wide range of immunoregulatory effects on both acquired and innate immunity (Chesler and Shoshkes 2002).

Epigenetics can be referred to as heritable changes of gene expression that are not caused by alterations in the primary nucleotide gene sequence (Wise and Charchar 2016). Epigenetic modifications are biochemical changes of the chromatin, in other words, DNA or histones, that are functionally relevant, but do not affect the nucleotide sequence of the genome (Potaczek et al. 2017). Generally, epigenetic modifications largely depend on general concept of what many scientists called writers, erasers and readers with their variability influencing the transition between heterochromatin and euchromatin. DNA methylation is one of the first identified and, at the same time, one of the most widely studied epigenetic modifications in humans. It occurs by covalent methylation of a cytosine within the CpG dinucleotides. Methylation at the fifth position of cytosine (5 mC) in DNA is a well-established epigenetic mark. It is distributed across the genome generally at CpG dinucleotides, which can occur in clusters known as CpG islands (Alashkar et al. 2019). The major role of DNA methylation in mammals is to repress gene expression by recruiting different silencing protein complexes, such as histone deacetylases (HDACs), which in turn can block the transcription machinery (Alashkar et al. 2019). Histone acetylation status is regulated by two groups of enzymes exerting opposite effects, histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). HATs catalyze the transfer of an acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to an amino acid group of the target lysine residues in the histone tails, which makes chromatin less compact and aids accessibility to the transcriptional machinery (Alhamwe et al. 2018). It has been proposed that the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression facilitated by miRNAs plays an important role in the fine-tuning of transcriptional programs in the context of bigger regulatory networks and in buffering fluctuations in gene expression resulting from random internal cellular modulation and/or environmental influences (Potaczek et al. 2017). Presently, no study has been done on the epigenetics of Type II interferon gamma in respect to rabies virus infection in mice brain. Consequently, this study investigated the epigenetic modifications associated with IFNG in Challenge virus standard (CVS) strain and Nigerian street rabies virus (SRV) infected mice. Our findings suggest that epigenetic modification via DNA methylation and histone acetylation may have played a role in the expression of type II interferon gamma in Rabies Virus infection.

Materials and methods

Animals, virus strain and reagents

Experimental animals (mice) used were purchased from the Animal house of the Department of Pharmacy, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Animal experiment was carried out at the Animal care facility of the Department of Veterinary Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. The laboratory RABV strain CVS and Nigerian street rabies strain (SV470) were obtained from National Veterinary Research Institute (NVRI), Vom, Jos, Nigeria. Animal housing and experimental protocols were performed according to the guidelines of the Nigerian council on Animal Care with the approval of the Ahmadu Bello University animal care committee. It is worthy of mention at this stage that, all the Researchers involved were fully vaccinated applicably prior to the commencement of the experimentations.

Experimental animal grouping

The experiment was carried out in three groups which include:

CVS infected mice

Nigeria street rabies virus infected mice

Non- infected / normal group

Each experimental group contained 18 mice each infected with SRV and CVS respectively with normal control group contained mice that were mock infected with normal saline.

Mouse inoculation test

The intramuscular mouse inoculation test (MIT) was conducted as previously described (Meslin et al. 1996). Group 1 and 2 were inoculated with 0.03 ml of 10% suspension of rabid mice brain (approximately 1 × 107 infectious particles of RABV) intramuscularly in the hind limb. Evaluation of disease progression was achieved by monitoring clinical symptoms and mortality. Three mice were chosen at random from each group on days 5, 7, 9, 11 and 13 post infections and sacrificed. Mice brain tissues were collected from all animals and stored in RNA later and phosphate buffer at −20 °C before being used for RNA/DNA extractions and Enzymes assay.

Direct fluorescent antibody test (DFAT)

Direct fluorescent antibody test (DFAT) as previously described (Ehizibolo et al. 2013) was used to test for the presence of Lyssavirus antigens. Impression smear preparations of harvested brain tissues were made. The positive and negative control slides were prepared in the same manner as the test sample using a fluorescent isothiocyanate-labeled anti-rabies virus monoclonal antibody (Fujirebio Diagnostics, Inc., Malvern, Pennsylvania, USA). The slides were observed under Flourescent Microscope (Zeiss, Axioskop, Germany) at × 20 magnification for the presence of Lyssavirus antigen.

RNA isolation

Isolate II RNA mini kit (Bioline Reagent Ltd., UK) was used to extract total RNA from 25 mg of mouse brain tissue according to manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality was assessed using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (ND 1000, USA).

Complimentary DNA (cDNA) synthesis

For cDNA synthesis, 500 ng of isolated RNA was converted to cDNA using SensiFASTcDNA Synthesis kit (Bioline Reagent Ltd. UK) following manufacturer’s instructions. For each 20 μl master mix, 2 μl of total RNA, 4 μl of 5x TransAmp buffer (contains anchored oligodT and random hexamer primers), 1 μl of reverse transcriptase and 13 μl DNase/RNase free water was used. PCR conditions were 25 °C for 10 mins, 42 °C for 15 mins and 85 °C for 5 mins. cDNA was stored at -20 °C for further analysis.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

For gene expression, 100 ng (1:5 dilution of stock solution) of cDNA was used whereas, 18 s rRNA was used as a reference gene. Primers for 18 rRNA are listed in Table 1. The cDNA (2 μl), 12.5 μl SensiFAST SYBR® No-ROX Mix RT-PCR Master Mix, 1 μl each forward and reverse primer (final concentrations 1 Um) and 8.5 μl DNase-free water were used for each 25 μl PCR master mix. Real-time PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 10 s and 72 °C for 20 s. The real-time PCR data were analyzed using the 2-∆∆CT relative quantification method.

Table 1.

Primers used for gene expression and MSqPCR analysis

| GENES | FORWARD PRIMER | REVERSE PRIMER | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFNG | 5′-AGCAACAACATAAGCGTCATT - 3′ | 5′-CCTCAAAACTTGGCAATACTCA- 3′ | (Barkhouse et al. 2015) |

| mIFNG | 5′- GTATAGGTGGGTATAGCGGGG −3′ | 5′- TAATCGAAAACTCCTCGAAA −3′ | (Meth primer) |

| uIFNG | 5′- TATAGGTGGGTATAGTGGGG −3′ | 5′-TATACCTAATCAAAAACTCCTCAAAATTAC -3′ | (Meth primer) |

| Actin B | 5′- GGGTTGGTTTGTATATTGATTTGAG −3′ | 5′- TAAAAAACCTATAACCCTCCCACTAA −3′ | (Meth primer) |

| 18S rRNA | 5′-GGGAGCCTGAGAAACGGC-3′ | 5′-GGGTCGGGAGTGGGTAATTT-3′ | (Lafon et al. 2017) |

DNA isolation

Isolate II Genomic DNA kit (Bioline Reagent Ltd. UK) was used to extract DNA from 25 mg of mice brain tissues according to manufacturer’s protocol. DNA quality was assessed using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (ND 1000).

Bisulfite modification

EZ DNA Methylation-Direct™ Kit (ZYMO Research, USA) was used to carry out bisulfite modification on 500 ng of the isolated DNA sample according to manufacturer’s protocol. As a control for efficiency of bisulfite conversion, 2 μl of converted DNA was used to carry out a conventional PCR against primers for converted DNA and checked using agarose gel electrophoresis. However, no amplicon was obtained which shows a successful conversion. All unmethylated cytosines were converted to uracil while the methylated cytosines within CpG sites remained unchanged during bisulfite conversion. After conversion and purification, DNA was eluted in 30 μl of the provided elution buffer.

Methylation specific quantitative PCR (MSQPCR)

For methylation specific quantitative (MSQPCR), 30 ng of bisulfite converted DNA was used with the 2x SensiFAST SYBR® No-ROX Mix RT-PCR according to manufacturer’s instructions. Primers specific for fully methylated and fully unmethylated IFNG promoter sequences (mIFNG, uIFNG) were used. For positive controls (100% values) and standard curves, unmethylated DNA (uDNA) and CG Genome Universal Methylated DNA (mDNA) (S7821; Millipore) were used. For reference gene, a primer pair corresponding to a specific β-actin sequence was used. Within this β -actin sequence, no CpG sites are present. Thus, the cytosines are always unmethylated, irrespective of methylation signals in other gene regions. Primers for mIFNG, uIFNG, and β -actin are listed in Table 1. For each 25 μl PCR, 2 μl eluate containing the bisulfite converted DNA, 12.5 μl SensiFAST SYBR® No-ROX Mix RT-PCR master mix, 1 μl each forward and reverse primer (final concentrations 1Um) and 8.5 μl DNase-free distilled water were used. Real-time PCR cycling conditions were initial incubation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 10 s and ending with incubation at 72 °C for 20 s.. Real-time PCR reactions were carried out in triplicate for each sample as a technical replicate. Methylation and unmethylation were calculated as percentage methylated region (PMR) and percentage unmethylation region (PUR) as follows (Hattermann et al. 2008):

DNA Methyltransferase (DNMT) and histone Acetyltransferase (HAT) assay

DNMT and HAT enzymes were colorimetrically measured using the mouse DNA methyltransferase (DNAM) ELISA Kit (GenAsia Biotech, Manilla, Philipines) and mouse Hat1 (histone acetyltransferase type B catalytic subunit) ELISA kit (Wuhan Fine Biotech, Wuhan, China) following manufacturer’s instructions. It works based on biotin double antibody sandwich technology and using DNMT and HAT antibody pre coated wells. Mouse brain tissue (60 mg each) was used for these assays.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times and where appropriate, values were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Student t-test and one-way ANOVA as the case may be were used to determine statistical difference. The level of significance was assessed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) at P < 0.05.

Results

Rabies virus (RABV) antigen (N protein) was qualitatively detected in mice inoculated with CVS and SRV from day 5 to 13 post infection (Table 2). Clinical manifestations with presence of ruffled fur, paralyzed hind and limb were used to support this as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antigen detection and clinical manifestations in CVS and SRV infected mice

| Days Post Infection | Clinical manifestation | Antigen detection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruffled fur | Paralyzed Hind limb | Total paralysis | DFAT | |

| CVS | ||||

| 5 | – | – | – | + |

| 7 | + | – | – | + |

| 9 | + | + | – | + |

| 11 | + | + | + | + |

| 13 | + | + | + | + |

| SRV | ||||

| 5 | – | – | – | + |

| 7 | – | – | – | + |

| 9 | + | – | – | + |

| 11 | + | + | – | + |

| 13 | + | + | + | + |

CVS: challenge virus standard strain, SRV: Nigerian street rabies virus, DFAT: Direct fluorescent antibody test, +: Presence of clinical manifestation/Antigen, −: Absence of clinical manifestation/Antigen

As shown in Fig. 1, a statistically significant (p < 0.05) increase in IFNG mRNA level was observed which was followed by a decrease in mRNA level as disease progressed in both CVS and SRV-infected mice.

Fig. 1.

Expression of IFNG gene in the brain tissue of RABV infected mice. Mean with different superscript are statistically significant (P < 0.05). CVS: challenge virus standard. SRV: street rabies virus, RABV: Rabies virus, IFNγ: interferon gamma.

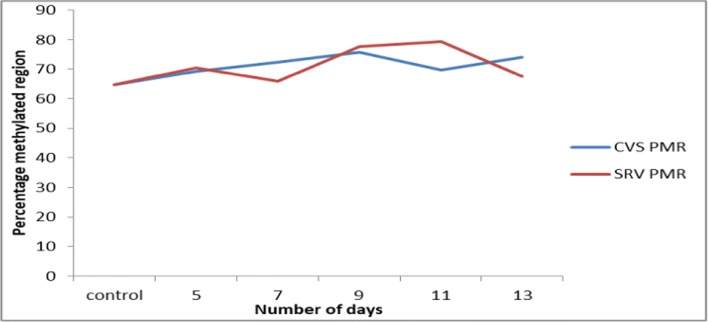

From the Methylation analysis (Fig. 2), there was an increase in the PMR of IFNG from normal to the test group in CVS induced-mice with simultaneous fluctuating pattern in both CVS and SRV groups as the disease progressed.

Fig. 2.

Percentage methylated region (PMR) of IFNG promoter in CVS and SRV infected mice brain tissue. CVS: challenge virus standard, SRV: street rabies virus, PMR: percentage methylated region

Table 3 shows activity of DNMT enzyme measured in the control group and the test group in both CVS and SRV. For CVS, the activity of the enzyme in the test group was higher than the control group except for days 9 and 13. For SRV, days 5 and 9 had higher activities than the control group and a fluctuation in activities as the disease progressed was observed in other days. The increase in the test group to the control group was statistically significant (p < 0.05) in both CVS and SRV.

Table 3.

DNA methyltransferase activity and Histone acetyltransferase of CVS and SRV infected mice brain tissue

| Number of Days | DNA Methyltransferase activity (ng/mg of protein/min/mg of brain tissue) | Histone acetyltransferase activity (ng/mg of protein/min/mg of brain tissue) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVS | SRV | CVS | SRV | |

| control | 46.3 ± 0.02 | 46.3 ± 0.02 | 3.7 ± 0.15 | 3.7 ± 0.15 |

| 5 | 48.1 ± 0.03* | 49.7 ± 0.09* | 2.2 ± 0.15* | 3.6 ± 0.15 * |

| 7 | 56.5 ± 0.02* | 38.3 ± 0.06* | 19.4 ± 0.16* | 23.3 ± 0.01* |

| 9 | 28.4 ± 0.04* | 48.2 ± 0.01* | 23.3 ± 0.01c* | 4.5 ± 0.15* |

| 11 | 50.7 ± 0.07* | 26.8 ± 0.01* | 21.1 ± 0.15* | 5.9 ± 0.15* |

| 13 | 43.6 ± 0.02* | 13.6 ± 0.03* | 35.8 ± 0.02* | 2.1 ± 0.09* |

Means with Asterisk (*) superscripts are statistically significant at (P < 0.05) as compared to control. CVS- Challenge virus standard, SRV- Street rabies virus

The Histone acetyltransferase (HAT) enzyme activity was measured in the control group and the test group in both CVS and SRV. For CVS, the activity of the enzyme in the control group was lower than the test group except for day 5, with fluctuations in activities in the test group as the disease progressed. An almost similar result was recorded for SRV; the activity of the enzyme in the control group was lower than the test group except for day 13 with fluctuations in activities in the test group as the disease progressed. The increase in the test group from the control group was statistically significant (p < 0.05) in both CVS and SRV induced-mice as shown in Table 3.

There was an observed difference in the activity of DNMT and HAT in the infected tissues in comparison to the normal group as regards to proportion (Table 4). The proportional increase of DNMT activity in all the infected samples was observed to be approximately 1 in CVS group. The same was recorded for SRV except for day 13. However, the proportional increase of HAT activity was higher in CVS group than SRV group and equally greater than that of DNMT.

Table 4.

Proportional increase in activity of DNMT and HAT relative to control in CVS and SRV groups

| Days Post Infection | DNMT (sample activity/control activity) | HAT (sample activity/ control activity) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | CVS 1.00 |

SRV 1.00 |

CVS 1.00 |

SRV 1.00 |

| 5 | 0.96 | 1.07 | 0.59 | 0.97 |

| 7 | 1.22 | 0.83 | 5.24 | 6.29 |

| 9 | 0.61 | 1.04 | 6.29 | 1.22 |

| 11 | 1.09 | 0.58 | 5.70 | 1.59 |

| 13 | 0.94 | 0.34 | 9.68 | 0.57 |

DNMT: DNA methyltransferase, HAT: Histone acetylase, CVS- Challenge virus standard, SRV- Street rabies virus

Discussion

Rabies remains an important public health problem, with estimated 59,000 annual deaths due to dog-mediated rabies globally (World Health Organization (WHO) 2018). Characteristic of encephalitic rabies in animals includes autonomic dysfunction, hyperexcitability, and aerophobia. Fever, bodily discomfort, general weakness, headache are symptoms of rabies in humans. As disease progresses, abnormal behavior, delirium, insomnia, hallucinations, and respiratory failure may occur (Burgos-Cáceres 2011a, b). The disease is often fatal once symptoms develop and it remains one of the most ancient and deadly of human infectious diseases (Burgos-Cáceres 2011a, b). Despite the discovery of rabies vaccine, rabies is still both a neglected disease and reemerging zoonosis (Burgos-Cáceres 2011a, b). Rabies virus usually evades the host’s immune system, and establishes the disease in the brain (Srithayakumar et al. 2014). Interferon gamma (IFN훾) production is essential for host resistance to many viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections (Tato et al. 2018). This is because the host immune response to viral infection is a key factor in determining viral pathogenicity and outcome of infection (Masatani et al. 2013). Consequently, the interferon (IFN) systems represent powerful defense elements of higher organisms that integrate innate and adaptive immunity (Brzózka et al. 2006). The pathogenic RABV has also evolved specific mechanisms to evade early recognition by the immune system and avoid premature death of infected neurons (Brzózka et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2005). RABV virulence relies on mechanism which suppresses the interferon response (Rieder and Conzelmann 2009; Ito et al. 2010; Chopy et al. 2011). In this study, herein, for the first time epigenetic modifications associated with type II gamma interferon gene in Rabies infection was reported.

CVS and SRV infected mice showed clinical manifestations such as ruffled fur, paralyzed hind limb and total paralysis from day 5 to 13 post infections. The presence of ruffled fur and hind limb paralysis started showing from day 7 in CVS and day 9 in SRV respectively. All infected samples tested positive for presence of Rabies virus antigen by DFAT which is in agreement with previous studies (Lafon et al. 2008).

The mRNA level of IFN훾from this study increased at the onset of rabies virus infection from day 5 with a decrease observed in the level of IFN훾 at day 11 as the disease progressed indicating that RABV may be responsible this change and may have devised a means to counter the effect of IFN훾. Previous studies have detected the immune response in the brain as early as 4 days after peripheral inoculation of RABV in mouse models (Srithayakumar et al. 2014). Similar studies (Wang et al. 2005; Johnson et al. 2006; Srithayakumar et al. 2014) also back this up. The findings in this study and others (Wang et al. 2005; Johnson et al. 2006; Lafon et al. 2008) show that interferon signaling pathway increases upon RABV infection.

Mechanisms of epigenetics have been implicated in viral infection associated with cancers and these include lymphomas, gastric cancers associated with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cervical and head and neck squamous cell cancers (HNSCCs) induced by human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs), becoming apparent that fundamental in the interplay between host cells and viruses are epigenetic changes (Galvan et al.,2015). To further buttress above points, DNA methylation after initial infection with Rabies virus by Methylation specific quantitative PCR (MSqPCR) was examined with results obtained as Percentage Methylated Region (PMR). Based on these findings, there was an observed increase in methylation in the test group from the control group, and a fluctuating pattern in methylation in both CVS and SRV groups as the disease progressed. This result does not follow the conventional pattern where hypermethylation leads to transcriptional repression. However, it has been reported that hypermethylation at 3′CpG may lead to changes in gene conformation, leading to activation of enhancers and subsequent recruitment of transcriptional factors, histone acetyltransferase, and hence transcriptional activation (Da-Hai et al. 2013). Another study indicates the use of alternate promoter, where the transcription machinery to the CpG island is blocked by methylation thereby allowing the use of the basic core promoter of the gene, whereas, in situations where the CpG island is unmethylated, transcription starts from the CpG island in preference to the basic core promoter of the gene (Halpern et al. 2014).

Similarly, the activity of DNA methyltransferase measured showed increased activity in the test group from the control group and fluctuated as the disease progressed showing a similar pattern as the result obtained for the PMR, since global DNMT assay was actually carried out in this study. Global methylation is likely to lead to abrupt mutation which may or may not lead to the up and down regulation of the interferon gamma gene in addition to hypermethylation at 3′CpG that may favor the transition from heterochromatin to euchromatin (Da-Hai et al. 2013). Histone acetylation generally leads to transcriptional activation as previously described (Kurdistani et al. 2004). From this study, there was an increase in Histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity in the test group as compared to the control group with a fluctuating pattern in the test group as the disease progressed. Furthermore, proportional increase in activity of DNMT and HAT in relation to control was checked. Both enzymes played their roles but there was a higher proportion of HAT compared to DNMT in both CVS and SRV groups and as such, the up and down regulations of the IFN훾 gene might likely be due to HAT rather than DNMT and it may be histone acetylation counterbalances the effects of DNA methylation here. It was therefore, hypothesized that methylation and histone acetylation may be central to the epigenetic modifications associated with IFN훾 gene in Rabies virus infection.

Conclusion

In conclusion, data from this study suggest that epigenetic modifications via DNA methylation and Histone acetylation may have played a role in the expression of type II interferon gamma in Rabies virus infection.

Limitations

Carrying out techniques such as Bisulfite sequencing would have given a better understanding at what points these methylations occurred and as such will have given a better insight to the work.

Further step/future plans

Further studies are needed for better understanding of these mechanisms using advanced techniques such as Chromatin immune-precipitation (Chip), Microarray, bisulfite sequencing and micro RNAs quantifications.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank and appreciate African Center of Excellence for Neglected Tropical Diseases and Forensic Biotechnology, (ACENTDFB) Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria for funding this important Project. The Association of African Universities (AAU) for supporting this work with their small grants for thesis and dissertation scheme.

Authors contributions

Conception: Abdulazeez Maryam, Grace S.N. Kia and Musa M. Abarshi.

Design: Aliyu Muhammad, Abdulazeez Maryam, Musa M. Abarshi and Grace S.N. Kia.

Execution: Ojedapo Comfort. E, Abdulazeez Maryam, David Dantong and Joy Cecilia Atawodi.

Interpretation: Aliyu Muhammad, Abdulazeez Maryam, Ojedapo Comfort. E, Grace S.N. Kia and Jacob K.P. Kwaga.

Writing and Proof reading: Ojedapo Comfort. E, Aliyu Muhammad, Grace S.N. Kia, Musa M. Abarshi, Abdulazeez Maryam, Joy Cecilia Atawodi, David Dantong and Jacob K.P. Kwaga.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maryam Abdulazeez, Email: abdulazeezmaryam108@gmail.com.

Grace S. N. Kia, Email: gracegracekia@yahoo.com

Musa M. Abarshi, Email: muawiyam@yahoo.co.uk

Aliyu Muhammad, Email: amachida31@gmail.com.

Comfort E. Ojedapo, Email: osinugacomfort@gmail.com

Joy Cecilia Atawodi, Email: joyceciliaatawodi@gmail.com.

David Dantong, Email: david.dantong@uniabuja.edu.ng.

Jacob K. P. Kwaga, Email: jacobkwaga@yahoo.com

References

- Alashkar B, Alhamdan F, Ruhl A. The role of epigenetics in allergy and asthma development. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;19:1–8. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhamwe A, Alhamwe BA, Khalaila R, Wolf J, Von Bülow V, Harb H, et al. Histone modifications and their role in epigenetics of atopy and allergic diseases. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14:39–16. doi: 10.1186/s13223-018-0259-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkhouse DA, Garcia SA, Bongiorno EK, Lebrun A, Faber M, Hooper DC. Expression of interferon gamma by a recombinant rabies virus strongly attenuates the pathogenicity of the virus via induction of. J Virol. 2015;89(1):312–322. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01572-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzózka K, Finke S, Conzelman K-K. Identification of the rabies virus alpha / Beta interferon antagonist : Phosphoprotein P interferes with phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor 3 identification of the rabies virus alpha / Beta interferon antagonist : Phosphoprotein P interferes. J Virol. 2005;79(12):7673–7681. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzózka K, Finke S, Conzelmann K-K. Inhibition of interferon signaling by rabies virus phosphoprotein P: activation-dependent binding of STAT1 and STAT2. J Virol. 2006;80(6):2675–2683. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2675-2683.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Cáceres S. Canine rabies: a looming threat to public health. Animals. 2011;1(2076–2615):326–342. doi: 10.3390/ani1040326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Cáceres S. Canine rabies: a looming threat to public. Animals. 2011;1(4):326–342. doi: 10.3390/ani1040326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler, D. A., & Shoshkes, C. (2002). The role of IFN- ␥ in immune responses to viral infections of the central nervous system, 13, 441–454 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chopy D, Pothlichet J, Lafage M, Megret F, Fiette L, Si-Tahar M, Lafon M. Ambivalent role of the innate immune response in rabies virus pathogenesis. J Virol. 2011;85(13):6657–6668. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00302-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da-Hai Y, Ware C, Waterand RA, Zhang J, Miao-Hsueh C, Gadkari M, Kunde-Ramamoorthy G, Lagina M, Nosavanh LS. Developmentally programmed 3 = CpG Island methylation confers tissue- and cell-type-specific transcriptional activation. Mol Cel Biol. 2013;33(9):1845–1858. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01124-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehizibolo D, Nwosuh C, Ehizibolo E, Kia G. Comparison of the fluorescent antibody test and direct microscopic examination for rabies diagnosis at the National Veterinary Research Institute, Vom, Nigeria. African Jurnal of Biomedical Research. 2013;12(1):73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan SC, García Carrancá A, Song J, Recillas-Targa F. Epigenetics and animal virus infections. Front Genet. 2015;6(March):4–6. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getachew N, Tesfaye B, Asaye M (2014) Rabies Virus Proteins and their Mechanism of Pathogenecity. 2(6):130–136

- Haji Abdolvahab, M., Mofrad, M. R. K., & Schellekens, H. (2016). Interferon Beta: from molecular level to therapeutic effects. International review of cell and molecular biology (Vol. 326). Elsevier Inc. 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Halpern KB, Vana T, Walker MD (2014) Paradoxical Role of DNA Methylation in Activation of FoxA2 Gene Expression during Endoderm Development. 289(34):23882–23892. 10.1074/jbc.M114.573469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hattermann K, Mehdorn HM, Mentlein R, Schultka S, Held-Feindt J. A methylation-specific and SYBR-green-based quantitative polymerase chain reaction technique for O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase promoter methylation analysis. Anal Biochem. 2008;377(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito N, Moseley GW, Blondel D, Shimizu K, Rowe CL, Ito Y, Masatani T, Nakagawa K, Jans DA, Sugiyama M. Role of interferon antagonist activity of rabies virus Phosphoprotein in viral pathogenicity. J Virol. 2010;84(13):6699–6710. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00011-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N, McKimmie CS, Mansfield KL, Wakeley PR, Brookes SM, Fazakerley JK, Fooks AR. Lyssavirus infection activates interferon gene expression in the brain. J Gen Virol. 2006;87(9):2663–2667. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kia GSN, Huang Y, Zhou M, Zhou Z, Gnanadurai CW, Leysona CM, Umoh JU, Kazeem HM, Ehizibolo DO, Kwaga JKP, Nwosu CI, Fu ZF (2018) Molecular characterization of a rabies virus isolated from trade dogs in Plateau State, Nigeria. Sokoto J Vet Sci 16(2):54–62. 10.4314/sokjvs.v16i2.8

- Kurdistani SK, Tavazoie S, Grunstein M, Hall B, Angeles L (2004) Mapping Global Histone Acetylation Patterns to Gene Expression. 117:721–733 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lafon M, Mégret F, Meuth SG, Simon O, Velandia Romero ML, Lafage M, et al. Detrimental contribution of the immuno-inhibitor B7-H1 to rabies virus encephalitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:7506–7515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafon M, Mégret F, Meuth SG, Romero MLV, Lafage M, Chen L, et al. Detrimental contribution of the immuno-inhibitor B7-H1 to rabies virus encephalitis 1. J Immunol. 2017;180:7506–7515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masatani T, Ito N, Ito Y, Nakagawa K, Abe M, Yamaoka S, et al. Importance of rabies virus nucleoprotein in viral evasion of interferon response in the brain. Microbiol Immunol. 2013;57(7):511–517. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meslin, F. X., Kaplan, M. M., & Koprowski, H. (1996). Laboratory techniques in rabies. World Health Organization, Geneva (4th ed.)

- Potaczek, D. P., Harb, H., Michel, S., BA, Alhamwe, Renz, H. and, Tost, J. (2017). Epigenetics and allergy: from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. Epigenomics [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rieder M, Conzelmann K (2009) Rhabdovirus evasion of the interferon system. J Interf Cytokine Res 29(9). 10.1089/jir.2009.0068 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Silva SR, Katz ISS, Mori E, Carnieli P, Vieira LFP, Batista HBCR, et al. Biotechnology advances: a perspective on the diagnosis and research of rabies virus. Biologicals. 2013;41(4):217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srithayakumar V, Sribalachandran H, Rosatte R, Nadin-Davis SA, Kyle CJ. Innate immune responses in raccoons after raccoon rabies virus infection. The Journal of General Virology. 2014;95(Pt 1):16–25. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.053942-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura N, Uda A, Inoue S, Kojima D, Hamamoto N. Gene expression analysis of host innate immune responses in the central nervous system following lethal CVS-11 infection in mice. Japanese Journal of Infections Disease. 2011;64:463–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tato, C. M., Martins, G. A., High, F. A., Dicioccio, C. B., Reiner, S. L., & Christopher, A. (2018). Cutting Edge: Innate Production of IFN- γ by NK Cells Is Independent of Epigenetic Modification of the IFN- γ Promoter. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1514 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z. W., Sarmento, L., Wang, Y., Li, X., Dhingra, V., Tseggai, T., Jiang B. Fu, Z. F. (2005). Attenuated Rabies Virus Activates , while Pathogenic Rabies Virus Evades , the Host Innate Immune Responses in the Central Nervous System. J Virol, 79(19), 12554–12565. 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wise IA, Charchar FJ (2016) Epigenetic modifications in essential hypertension. Int J Mol Sci 17(4). 10.3390/ijms17040451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2018). WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies, third report

- Yousaf MZ, Qasim M, Zia S, Khan R, Ashfaq UA. Rabies molecular virology , diagnosis , prevention and treatment. J Virol. 2012;9:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Zhou Z, Kia GSN, Gnanadurai CW, Leyson CM, Umoh JU, et al. Complete genome sequence of a street rabies virus isolated from a dog in Nigeria. Genome Announcements. 2013;6(1):6–7. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00214-12.Copyright. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]