Abstract

Caregivers of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities are often stressed due to the demands of the job, including the nature and severity of challenging behaviors of the clients, work conditions, degree of management support for the staff, and the demands of implementing some interventions under adverse conditions. Mindfulness-Based Positive Behavior Support (MBPBS) and PBS alone have been shown to be effective in assisting caregivers to better manage the challenging behaviors of clients with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The aim of the present study was to undertake a head-to-head assessment of the effectiveness of MBPBS and PBS alone in a 40-week randomized controlled trial. Of the 123 caregivers who met inclusion criteria, 60 were randomly assigned to MBPBS and 63 to PBS alone, with 59 completing the trial in the MBPBS condition and 57 in the PBS alone condition. Results showed both interventions to be effective, but the caregiver, client, and agency outcomes for MBPBS were uniformly superior to those of PBS alone condition. In addition, the MBPBS training was substantially more cost-effective than the PBS alone training. The present results add to the evidence base for the effectiveness of MBPBS and, if independently replicated, could provide an integrative health care approach in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Keywords: Mindfulness-Based Positive Behavior Support, MBPBS, PBS, Stress, Compassion fatigue, Burnout, Secondary traumatic stress, Perceived stress, Cost-effectiveness

Introduction

Most paid caregivers provide services with love and compassion. Caregiving can produce both positive and negative effects on the caregiver (Harmell et al. 2011; Hastings and Horne 2004). However, in the long term, it often leads to stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue in the caregivers. They experience psychological stress as a result of their emotional and physiological reactions when they are unable to cope with their job-related demands. Burnout is “a persistent, negative, work-related state of mind in ‘normal’ individuals that is primarily characterized by exhaustion, which is accompanied by distress, a sense of reduced effectiveness, decreased motivation, and the development of dysfunctional attitudes and behavior at work” (Schaufeli and Buunk 2003, p. 388). It results from the cumulative effects of persistent occupational stress and may evidence as emotional exhaustion, irritability, frustration, general anxiety, dysthymia, insomnia, and loss of work effectiveness (Maslach et al. 2001). Compassion fatigue is the reduced capacity of the caregiver to be empathic due to the constant demands of caregiving. It often leads to reduced productivity, increased absenteeism of the caregiver, low levels of personal effectiveness, and personal psychological distress that may compromise the quality of caregiving (Adams et al. 2006; Epp 2012; Quenot et al. 2012).

Caregivers of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities are known to exhibit high levels of stress and burnout (Skirrow & Hatton 2007). For example, research indicates between 25 and 32% of caregivers surveyed report stress and burnout (Hastings et al. 2004; Hatton et al. 1999). Many factors have been found to elevate caregiver stress, including the nature and severity of challenging behaviors of the clients, work conditions, degree of management support for the staff, in-service training, and career path issues (Devereux et al. 2009a, b). As a result, some caregivers engage in informal but often less than optimal coping strategies to manage their rising stress, including the use of substances, emotional eating—typically unhealthy foods—and other lifestyle changes (Piko 1999). The cumulative effects of heightened stress often lead to health complications, ranging from minor but persistent coughs and colds to chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes (Melamed et al. 2006). When caregivers are stressed at their workplace, there is high likelihood that their productivity declines, clients receive less caregiver attention and assistance, and there is decreased social interaction (Rose et al. 1998), as well as increased risk for physical and mental abuse of the clients (White et al. 2003). Eventually, there is increased caregiver absenteeism and turnover that leads to a decline in the quality of care and loss of continuity of care (Lin et al. 2009).

A number of intervention approaches have been advanced to alleviate stress in paid caregivers. Given that clients’ behaviors often lead to caregiver stress, an early approach has been to teach caregivers effective behavioral techniques that would enable them to better manage their clients’ challenging behaviors. Research suggests that when used with consistency and procedural fidelity, behavior management procedures—especially in the form of positive behavior support—are very effective in controlling aggressive and other disruptive behaviors of clients (MacDonald 2016; Morris and Horner 2016). However, there has been little evidence to show that caregiver stress is appreciably reduced, probably because other extenuating factors related to job stress remain. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that caregiver stress is exacerbated by the demands of implementing such procedures under adverse conditions (Allen et al. 2005; Didden et al. 2016).

An alternative approach has been to teach caregivers effective ways of directly managing their psychological distress. These approaches include specific components of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and mindfulness-based procedures (Leoni et al. 2016). For example, Noone and Hastings (2009, 2010) reported a significant decrease in psychological distress in caregivers following a brief training course that used three key components of ACT—acceptance, cognitive mindfulness, and values clarification—even when faced with a slight increase in job stress. In another study, caregivers were reported to have decreased stress, enhanced psychological well-being, and increased job satisfaction following a training course that included elements of mindfulness and positive psychology (Brooker et al. 2013). While certainly effective in reducing caregiver stress, this approach does not speak to the challenging behaviors of the clients.

Another approach has emerged in the research literature that effectively combines the previous two approaches and enables caregivers to better manage not only their own stress but also their clients’ challenging behaviors. This approach combines mindfulness-based procedures that teach caregivers how to take care of themselves in a mindful manner, which reduces their stress, and to more skillfully use positive behavior support interventions with their clients, which reduces the clients’ challenging behaviors (Singh et al. 2016a). For example, in a multiple baseline design study, Singh et al. (2015) evaluated the effects of a Mindfulness-Based Positive Behavior Support (MBPBS) course for caregivers. The results showed reduced caregiver psychological stress, no caregiver turnover, and gradual reduction and elimination of the use of physical restraints for aggressive behaviors of the clients. These findings were replicated and extended in a proof-of-concept quasi-experimental study (Singh et al. 2016b). Finally, in a randomized controlled trial that compared the effects of MBPBS against a treatment-as-usual control condition, MBPBS was comparatively more effective than treatment-as-usual in reducing the caregivers’ perceived psychological stress, use of physical restraints, and the need for emergency medications for the aggressive behavior of their clients (Singh et al. 2016c). Furthermore, the results indicated a strong correlation between caregiver training in MBPBS and statistically significant reductions in the aggressive behavior of the clients.

These studies attest to the effectiveness of MBPBS in enabling caregivers to self-manage their stress under adverse job-related conditions, including the unpredictable challenging behaviors of their clients, as well as in enhancing the quality of life of their clients by reducing the use of restrictive procedures such as physical restraints, emergency medication, and one-to-one staffing. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the comparative effects of MBPBS and PBS alone on caregiver variables (i.e., perceived stress, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue), client variables (i.e., frequency of aggressive behavior, staff injury, peer injury), and agency variables (i.e., use of physical restraints, emergency medication, one-to-one staffing, staff turnover, cost-effectiveness).

Method

Participants

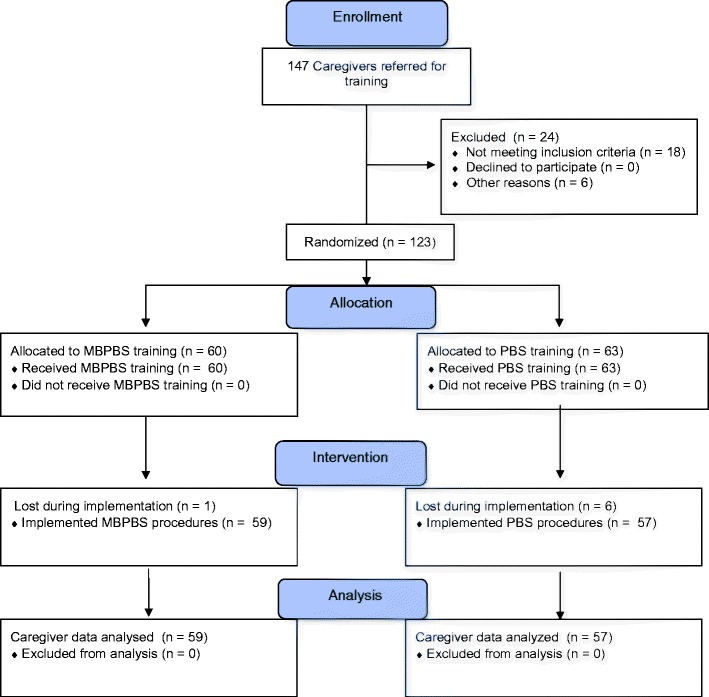

The participants were caregivers from community group homes that provided services to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The group homes were administered by the same agency and all were located in the same general vicinity. A total of 147 caregivers were referred by the agency for training. Of these, 18 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (i.e., full-time employment, consent to participate in the training, and availability during the training) and 6 were excluded for other reasons (i.e., medical condition, imminent transfer to another work site). Using a random number generator, the remaining 123 caregivers were randomized into MBPBS or PBS experimental conditions. Of the 60 caregivers randomized to the MBPBS condition, 1 dropped out and of the 63 caregivers randomized into the PBS condition, 6 dropped out during the trial. Figure 1 presents a CONSORT participant flow diagram. The caregivers in each condition were responsible for serving 40 individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities who were at the mild to moderate level of functioning. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the caregivers and the individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in their care.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow through the trial (CONSORT diagram)

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the caregivers and individuals with IDD in the MBPBS and PBS conditions

| MBPBS | PBS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregivers | Individuals with IDD | Caregivers | Individuals with IDD | |

| Number of participants | 60 | 40 | 63 | 40 |

| Mean age/years (SD) | 44.05 (9.71) | 40.65 (7.92) | 42.84 (8.87) | 43.88 (9.46) |

| Age range (years) | 23–64 | 29–59 | 29–61 | 24–63 |

| Gender: males | 17 (28.33%) | 22 (55%) | 19 (30.15%) | 26 (65%) |

| Level of functioning | ||||

|

Mild Moderate |

na na |

27 (67.5%) 13 (32.5%) |

na na |

28 (70%) 12 (30%) |

| Number of individuals on psychotropic medications | na | 23 (57.5%) | na | 20 (50%) |

| Number of individuals with mental illness | na | 23 (57.5%) | na | 20 (50%) |

| Number of individuals with behavior plans for aggressive behavior | na | 25 (62.5%) | na | 23 (57.5%) |

na not applicable, IDD intellectual and developmental disabilities

Procedure

Experimental Design

This was a randomized controlled trial (RCT), with two active experimental conditions: MBPBS and PBS. For each condition, training was provided during the first 10 weeks, with intervention data collected during the following 30 weeks.

Experimental Conditions

MBPBS

The MBPBS protocol was the same 7-day course as that used by Singh et al. (2016b, c). Briefly, the course was presented in three parts, spread over the first 10 weeks of the trial. The first part was an 8-h day on the first day of week 1 of training, followed by daily practice for 4 weeks. The second part included five 8-h days (i.e., 40 h) during week 5, followed by daily practice for 4 weeks. The third part was again an 8-h day on the first day of week 10, followed by daily practice for the rest of the week. The training was provided in a group format of 15 to 20 caregivers in each group. The training was followed by 30 weeks of intervention during which no formal training was provided, but all caregiver questions regarding the practices and daily use of mindfulness and related meditations were addressed. In addition, the caregivers were provided with informal meditation practices that they could use in specific situations arising in the work situations. Table 2 presents the MBPBS program and a brief outline of each day’s training. Further details of the MBPBS procedure can be found in Singh et al. (2016a, b, c).

Table 2.

Outline of the 7-day MBPBS program

|

Day 1 (first 1-day training; week 1) |

Samatha meditation Kinhin meditation Vipassanā meditation Five hindrances—sensory desire, ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and remorse, and doubt Daily logs and journaling |

|

Day 2 (first day of 5-day intensive training; week 5) |

Review of meditation practice Introduction to the Four Immeasurables (Brahmavihara: metta—loving kindness; karuna—compassion; mudita—empathetic joy; upekkha—equanimity) Equanimity meditation Beginner’s mind Applications to PBS practice |

| Day 3 |

Review of day 2 instructions and practices Further instructions on the Four Immeasurables Equanimity meditation Loving-kindness meditation Being in the present moment Applications to PBS practice |

| Day 4 |

Review of days 2 and 3 instructions and practices Further instructions on the Four Immeasurables Equanimity meditation Loving-kindness meditation Compassion meditation The three poisons—attachment, anger, and ignorance Applications to PBS practice |

| Day 5 |

Review of days 2 to 4 instructions and practices Further instructions on the Four Immeasurables Equanimity meditation Loving-kindness meditation Compassion meditation Joy meditation Attachment and anger—shenpa and compassionate abiding meditations Applications to PBS practice |

| Day 6 |

Review of days 2 to 5 instructions and practices Review and practice Samatha, Kinhin, and Vipassanā meditations Review of the Four Immeasurables Practice equanimity, loving kindness, compassion, and joy meditations Attachment and anger—meditation on the soles of the feet Review of applications to PBS practice Review of the MBPBS training program |

|

Day 7 (second 1-day training; week 10) |

Review of the meditation instructions and practices (daily logs) Review and practice Samatha, Kinhin, and Vipassanā meditations Review of the Four Immeasurables Practice equanimity, loving kindness, compassion, and joy meditations Emotion regulation and anger—meditation on the soles of the feet Instructions for practicing three ethical precepts—refrain from (a) harming living creatures, (b) taking that which is not given, and (c) incorrect speech Applications to PBS practice Review of the 7-day MBPBS training program |

MBPBS Trainer

The trainer had a life-long practice of meditation and was well versed in mindfulness-based training. In addition, the trainer was a behavior analyst at the BCBA-D level with extensive experience in developing and implementing PBS plans.

Fidelity of MBPBS Training

Fifteen randomly selected 12-min videotaped segments from each day of the 7-day training (i.e., 105 training segments) were rated for fidelity of MBPBS training by two independent raters, one an expert in mindfulness and the other an expert in PBS. The fidelity of MBPBS training was rated at 100% for meditation instructions and for principles, components of PBS plans, and applications of PBS.

PBS

The training for PBS followed the same three-part 7-day training timeline as in the MBPBS training, and the specific contents of the training replicated the Singh et al. (2016b, c) protocol. As with the MBPBS protocol, training was provided in a group format of 15 to 20 caregivers in each group. There are at least four overlapping models of PBS training (MacDonald 2016). The PBS training used in this study was based on the Dunlap et al. (2000) model that substantially overlaps with the earlier model of Anderson et al. (1993, 1996). In general, the training format included cross-setting multidisciplinary collaboration, the use of a case study format with an actual client, a dynamic training process that emphasized principles of PBS derived from its practical applications, and an emphasis on comprehensive outcome goals. Training included the development of support strategies based on setting-specific functional assessment that were proactive and could be maintained in the natural environment of the clients. The focus of the PBS plan was on developing and strengthening positive behavior more than on managing or eliminating challenging behaviors, with the intent of enhancing each client’s long-term quality of life. Further details of PBS procedures can be found in MacDonald (2016) and Morris and Horner (2016).

PBS Trainer

The trainer was a behavior analyst at the BCBA level with over 25 years of experience in developing and implementing PBS plans, as well as in providing in-service training to support staff in developing and implementing PBS plans.

Fidelity of PBS Training

The same fidelity assessment procedure was used as for the MBPBS training. Fifteen randomly selected 12-min videotaped segments from each day of the 7-day training (i.e., 105 training segments) were rated for fidelity of PBS training by two independent raters, both experts in PBS. The fidelity of PBS training was rated at 100% for principles, components of PBS plans, and applications of PBS.

Measures

Caregiver Variables

Perceived Stress Scale-10

The Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10; Cohen et al. 1983) is a 10-item self-report questionnaire of perceived stress operationalized as subjective evaluation of lack of control, unpredictability, and overload in participants’ daily life (Cohen and Williamson 1988). The PSS-10 uses a five-point Likert scale response format, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), and the total score is calculated after reverse coding items 4, 5, 7, and 8 and then adding the scores of all 10 items. Higher scores indicate greater levels of perceived stress. The PSS-10 has satisfactory psychometric properties with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78 (Cohen & Williamson 1988) and was 0.81 for the present study. A recent Rasch analysis confirmed the robust psychometric properties of the PSS-10 and produced conversion tables for converting ordinal responses into interval-level data to increase reliability of assessment and to satisfy assumptions of parametric statistics (Medvedev et al. 2017). Caregivers completed the PSS-10 on the first day of training and on the last day of post-training.

Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL)

The ProQOL (Stamm 2010) is a 30-item self-report scale assessing professional quality of life. It includes two inversely related main domains, compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue includes two subscales, burnout and secondary traumatic stress. The ProQOL is presented in a 5-point Likert format, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Burnout subscale includes five negatively worded items (1, 4, 15, 17 and 29) that are reverse coded before calculating the total subscale score. The subscale scores are calculated by adding item scores of each subscale, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue (i.e., burnout and secondary traumatic stress), respectively. The ProQOL subscales have satisfactory psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.88 for compassion satisfaction, 0.75 for burnout, and 0.81 for secondary traumatic stress (Stamm 2010). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.86, 0.73, and 0.79 for compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress, respectively, for the present study. Caregivers completed the ProQOL on the first day of training and on the last day of post-training.

Training Attendance

Caregiver attendance for both MBPBS and PBS 7-day training was recorded.

Meditation Practice

Caregivers were required to record in their daily logs the total time they spent in meditation practice each day during the 10-week training period and during the 30 weeks of intervention. Although meditation was a part of the MBPBS condition only, to control for extraneous variables on outcomes, caregivers in the PBS condition were also required to log their meditation time if they had or started a personal meditation practice during the study period.

Client Variables

Aggressive Events

The standard procedure of the agency running the group homes was followed for collecting data on aggressive events, which were defined as an individual hitting, biting, scratching, punching, kicking, slapping, or destroying property. As per agency policy, staff recorded each instance of an aggressive event on an incident reporting form at the point of occurrence and this was later entered in the agency’s incident management database. Each incident was double-checked by the home supervisor for occurrence and accuracy of reporting. The reliability of reporting and logging the occurrence of aggressive events was 95% (range 91 to 100%).

Staff Injury

Staff injury was defined as any aggressive act by a client directed at a caregiver, with physical contact, requiring medical examination, first aid, or medical care. Each instance of staff injury was recorded on an incident reporting form at the point of occurrence. The reliability of documenting incidents of staff injury was 100%.

Peer Injury

Peer injury was defined as any aggressive act by a client directed at a peer, with physical contact, requiring medical examination, first aid, or medical care. Each instance of peer injury was recorded on an incident reporting form at the point of occurrence. The reliability of documenting incidents of peer injury was 100%.

Agency Variables

Physical Restraints

Standard agency procedure was followed for collecting data on physical restraints, which was defined as a brief physical hold of an aggressive individual by a caregiver when there was imminent danger of physical harm to the individual, peers, or staff and the behavior could not be controlled with verbal redirection. Caregivers recorded each instance of the use of a physical restraint at the point of occurrence and this was later entered in the agency’s risk management database. Each use of physical restraint was double-checked by the home supervisor for occurrence and accuracy of reporting. The reliability of reporting and logging the occurrence of physical restraints was 100%.

Emergency Medication

Emergency medication was prescribed by a physician and administered by a registered nurse for behavioral or psychiatric emergencies. Emergency medication for medical or other conditions was not included in this category. Emergency medication was prescribed for the calming of a client who was aggressive and could not be managed by other means, including physical restraints. Each administration was counted as one event as recorded by a registered nurse in the individual’s Medication Administration Record (MAR). Only those administrations that were prescribed specifically as emergency medication for aggressive behavior, as defined above, were counted. The reliability of recording the administration of emergency medication in the client’s MARS was 100%.

One-to-one Staffing

One-to-one staffing is used when a client’s aggressive or destructive behavior cannot be managed through clinical interventions and the safety of the client, staff, and peers is in question. It is defined as the level of enhanced observation ordered by a physician or psychologist for a client who engages in aggressive or destructive behavior. At the group home, each client’s treatment team determined the need for level of supervision, the administration assigned the staff, and the home manager ensured the provision of level of supervision on a shift-by-shift basis. Level of supervision staff was recorded as being present for the assigned duties 100% of the time.

Staff Turnover

The agency’s Human Resource Department provided the staff turnover data. The data included all instances of any caregiver participating in either experimental condition leaving the employment of the agency due to staff injury on the worksite during the 40 weeks of the study period.

Cost-effectiveness

The agency’s Finance Department provided cost data on (1) work days lost due to staff injury, (2) instances of one-to-one staffing, (3) staff needing medical and physical rehabilitation therapy due to injury, (4) staff resigning due to staff injury who were replaced, (5) staff required for MBPBS and PBS training, and (6) temporary staff required during MBPBS or PBS training. All costs were included, regardless of whether the costs were borne by the agency or by workers’ compensation.

Data Analyses

The effectiveness of the MBPBS and PBS interventions was evaluated using the following analytical strategies. For several count variables that represent ratio-level data, a group count for an entire condition was used instead of a count for individuals within a condition. These variables included the number of aggressive events per week, the number of physical restraints used per week, the number of emergency medication administrations per week, and the number of additional one-to-one staffing needed per week. As these variables are not at the individual level, they do not lend themselves to traditional analyses for RCTs. Therefore, change across time within each condition was examined by treating each group as an n of 1. In doing so, we plotted the count of each variable for each condition across all weeks of the study. Multiple linear regression (MLR) was used to estimate to what extent the client and caregiver variables were predicted by intervention type (MBPBS vs. PBS) after controlling for the effect of time. Effect size in regression analysis is reflected by R2 (which is the percentage of variance explained by the linear relationship between two variables) and specific effects by R2 change, which is interpreted as R2 of 0.02 = small, 0.15 = medium, and 0.26 = large (Cohen 1988). All study variables were tested and met assumptions of MLR: skewness and kurtosis values within ± 1, no significant outliers, and no evidence of multicollinearity (variance inflating factor < 5).

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants in the MBPBS and PBS conditions were compared by series of chi-square and independent samples t tests and indicated no statistically significant differences between the groups (all p’s > 0.05). In terms of training attendance, all caregivers in both MBPBS and PBS conditions attended all 7 days of training. All 59 caregivers in the MBPBS condition began their meditation practice on the evening of the first of the 7 days of training. The caregivers in this condition gradually increased their meditation time from a few minutes each day to an average of 26 min of daily practice (range = 20 to 41 min), with occasional meditation holidays. None of the 57 caregivers in the PBS condition had or began a daily meditation practice during the course of the study.

Caregiver Outcomes

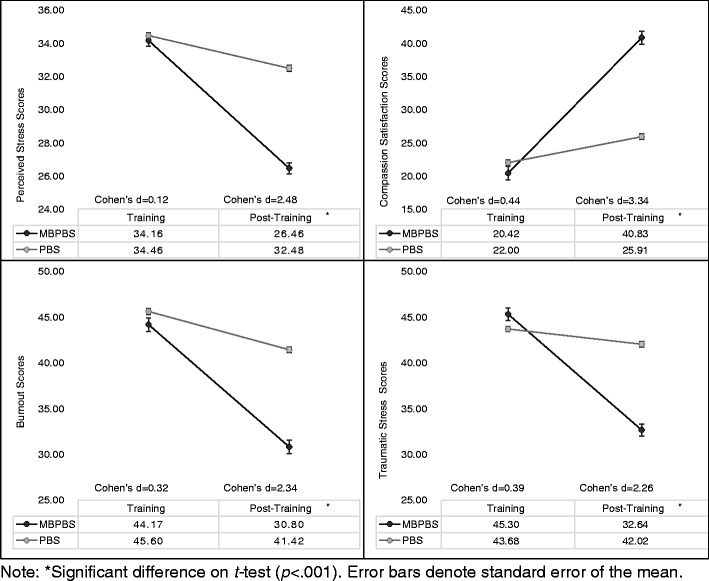

Table 3 includes the MLR results for each psychological outcome measured for caregivers with time and intervention type as predictors. The time effect and the effects of MBPBS comparison with PBS condition after controlling for time were statistically significant for all four psychological measures (all p’s < .001), with effect sizes ranging from small to large (R2 change 0.10–0.47). These data indicate that both the MBPBS and the PBS conditions were effective in increasing compassion satisfaction and in reducing burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and perceived stress. However, the MBPBS condition was more effective, explaining a further 10 to 18% of the variance in psychological data with all β coefficients significant and above 0.31, reflecting substantial psychological improvement in the caregivers.

Table 3.

Summary of the multiple linear regression analyses predicting caregiver variables including compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress (ProQOL), perceived stress (PSS-10), and overall staff turnover with time and intervention type as predictors

| Model | R2 | R2 change | Variable | Standardized β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProQOL: compassion satisfaction | |||||

| 1 | .47 | .47 | < .001 | ||

| Time | .69 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .60 | .13 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | .36 | < .001 | |||

| ProQOL: burnout | |||||

| 1 | .42 | .42 | < .001 | ||

| Time | − .65 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .60 | .18 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .43 | < .001 | |||

| ProQOL: secondary traumatic stress | |||||

| 1 | .37 | .37 | < .001 | ||

| Time | − .61 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .47 | .10 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .31 | < .001 | |||

| PSS-10: perceived stress | |||||

| 1 | .41 | .41 | < .001 | ||

| Time | − .64 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .58 | .16 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .41 | < .001 | |||

| Staff turnover | |||||

| 1 | .00 | .00 | .774 | ||

| Time | − .03 | .774 | |||

| 2 | .05 | .05 | .050 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .22 | .050 | |||

aEffect of MBPBS comparison with PBS condition after controlling for time

Figure 2 shows the change in caregiver psychological measures between training and post-training in the MBPBS and PBS conditions including perceived stress, compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. A larger decrease in the perceived stress, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress scores and a larger increase of compassion satisfaction were observed from the first day of training (time 1) to the last day of intervention (i.e., post-training) (time 2) in the MBPBS condition compared to the PBS condition. It can be seen that there were no significant differences between conditions on the first day of training, but all differences became statistically significant (all p’s < .001) with a large effect size when measured on the last day of post-training (i.e., at the end of the 40 weeks).

Fig. 2.

Perceived stress (PSS-10), compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress (ProQOL) mean scores of caregivers measures based on responses on the first day of the MBPBS and PBS training and the last post-training day for both conditions

Client Outcomes

Table 4 shows the results of MLR analysis conducted individually for each client outcome variable with time and intervention type as predictors. Significant effects of both time and MBPBS comparison with PBS condition after controlling for time were observed in all client variables with all p values < .001. The effect size of time for both MBPBS and PBS conditions was large for all client variables explaining between 40 and 63% of variance in the data, which indicates that both interventions were very effective in reducing the challenging behaviors of clients. Even after controlling for time effect, the MBPBS condition demonstrated small to moderate effect size in reducing aggression, staff injuries, and peer injuries, compared to the PBS condition (R2 change 0.07–0.24). Standardized β coefficient with negative sign indicates reduction in the outcome variable due to the effect of the predictor variable in standard deviation units. After controlling for time, all β coefficients reflecting difference between the MBPBS and the PBS conditions were significant with values ranging from − 0.27 to − 0.49, suggesting noticeable behavior change.

Table 4.

Summary of the multiple linear regression analyses predicting client variables including aggression by client, staff injuries, and peer injuries, and agency variables including physical restraints, emergency medication, and 1:1 staffing, with time and intervention type as predictors

| Model | R2 | R2 change | Variable | Standardized β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression by client | |||||

| 1 | .63 | .63 | < .001 | ||

| Time | − .79 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .75 | .12 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .35 | < .001 | |||

| Staff injuries | |||||

| 1 | .60 | .60 | < .001 | ||

| Time | − .78 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .67 | .07 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .27 | < .001 | |||

| Peer injuries | |||||

| 1 | .40 | .40 | < .001 | ||

| Time | − .64 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .65 | .24 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .49 | < .001 | |||

| Physical restraints | |||||

| 1 | .56 | .56 | < .001 | ||

| Time | − .75 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .71 | .15 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .39 | < .001 | |||

| Emergency medication | |||||

| 1 | .60 | .60 | < .001 | ||

| Time | − .77 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .75 | .15 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .29 | < .001 | |||

| 1:1 Staffing | |||||

| 1 | .43 | .43 | < .001 | ||

| Time | − .66 | < .001 | |||

| 2 | .80 | .37 | < .001 | ||

| aMBPBS vs. PBS | − .37 | < .001 | |||

aEffect of MBPBS comparison with PBS condition after controlling for time

Agency Outcomes

Table 4 also shows the results of MLR analysis conducted individually for three of the agency outcome variable with time and intervention type as predictors. Significant effects of both time and MBPBS comparison with PBS condition after controlling for time were observed in all three agency variables with all p values < .001. After controlling for time effect, the MBPBS condition demonstrated moderate to large effect size in reducing the use of physical restraints, one-to-one staffing, and the necessity to administer emergency medication compared to the PBS condition (R2 change 0.15–0.37). Standardized β coefficient with negative sign indicates reduction in the outcome variable due to the effect of the predictor variable in standard deviation units. After controlling for time, all β coefficients reflecting difference between the MBPBS and the PBS conditions were significant with values ranging from − 0.29 to − 0.39, suggesting noticeable behavior change.

In terms of staff turnover, one caregiver in the MBPBS condition and six in the PBS condition terminated their employment with the agency, all due to job-related injuries. Table 3 shows the MLR for combined staff turnover data in both conditions as an outcome variable and time and intervention type as predictors. Time effect was not significant but, even with limited amount of staff turnover data, the MBPBS condition had marginally significant effect (p = .05) compared to the PBS condition with standardized β of − 0.22 that explained 5% of variance in these data.

Table 5 shows cost-effectiveness comparison between the MBPBS and PBS conditions. The MBPBS condition was more cost-effective than PBS on a number of variables, including lost days of work due to staff injury, cost of additional one-to-one staffing, number of staff needing rehabilitation therapy, number of staff resignations due to injuries, and costs of training new staff. When compared to the PBS alone condition, implementing the MBPBS course not only produced comparatively more clinically and statistically significant changes for both the caregivers and their clients, but also produced a cost savings of $512,418.00 to the agency providing the services.

Table 5.

Comparative costs for training and implementation of MBPBS and PBS for 40 weeks

| Cost variables | Cost | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBPBS | PBS | MBPBS | PBS | |

| Lost days of work due to staff injury | 61 | 653 | $8784.00 | $94,032.00 |

| Number of staff days and cost of 1:1 staff | 53 | 192 | $7632.00 | $27,648.00 |

| Number of staff needing medical and physical rehabilitation therapy | 1 | 22 | $19,500.00 | $429,000.00 |

| Number of staff resigned due to staff injury and training costs for new hires | 1 | 6 | $1726.00 | $10,356.00 |

| Number of training days and cost of MBPBS and PBS training | 7 | 7 | $21,000.00 | $7000.00 |

| Cost of temporary staff during MBPBS or PBS training | 60 | 63 | $60,480.00 | $63,504.00 |

| Total additional costs for the two time periods | $119,122.00 | $631,540.00 | ||

| Total overall savings | $512,418.00 | |||

NEO new employee orientation

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of training caregivers in MBPBS and PBS. The results showed that while both interventions were effective, caregiver training in MBPBS was uniformly superior to PBS alone. For example, when compared to the PBS condition, caregivers in the MBPBS group showed a statistically significant increase in compassion satisfaction, a decrease in compassion fatigue (i.e., burnout and secondary traumatic stress), and a decrease in perceived stress. In addition, caregivers in the MBPBS condition gradually reduced and eliminated the use of restrictive procedures (i.e., physical restraints and emergency medications). The clients of caregivers trained in MBPBS showed statistically significant reductions in aggressive behavior, staff injuries, and peer injuries when compared to clients whose caregivers were trained in PBS alone. There was much lower staff turnover from the MBPBS group (n = 1) of caregivers than from the PBS group (n = 6). Finally, the MBPBS training was cost-effective by just over a half million dollars, thus making it clinically and economically attractive to service providers.

A recent research review indicated that mindfulness-based interventions are emerging as an evidence-based approach for assisting caregivers of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities to manage their stress (Donnchadha 2017). While such a conclusion may be somewhat premature given the heterogeneity of mindfulness-based interventions, and the lack of independent research groups replicating specific mindfulness-based interventions, the field clearly indicates that engaging in mindfulness-based practices does assist caregivers in improving their well-being (Brooker et al. 2013; Noone and Hastings 2010; Singh et al. 2016b, c). Furthermore, when caregivers engage in mindfulness-based practices, they enhance the quality of life of their clients by reducing or eliminating the use of restrictive procedures, such as physical restraints and emergency psychotropic medications (Brooker et al. 2014; Singh et al. 2009, 2015). In addition, similar positive findings have been reported when parents and teachers use MBPBS with their children and students, respectively (Singh et al. 2013, 2014).

The present study braided two empirically validated approaches to caregiver training in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities. Both PBS and MBPBS have similar general intent in improving quality of life outcomes, but with very different underlying philosophies and purported mechanisms of change. In broad terms, PBS is a science-based experimental discipline that focuses on changing behavior (Hieneman and Fefer 2017; Lucyshyn et al. 2015), while mindfulness (without PBS) is an experiential approach to training one’s own mind to behave (Kabat-Zinn 1994). The two approaches are synergistic, and regardless of their purported underlying mechanisms, both are open to scrutiny using traditional methods of scientific inquiry. Thus, the braiding of these two approaches in MBPBS for reducing caregiver stress and for enhancing the quality of life of the clients makes perfect clinical sense. The mindfulness-based procedures provide the experiential component that enables caregivers to manage their stress, and the PBS procedures enable them to more effectively manage the behavior of their clients.

Van Gordon et al. (2015) have explicated and popularized the notion that mindfulness-based interventions can be divided into first- and second-generation programs. They noted that the first generation of interventions broke new ground in terms of acceptance of mindfulness within the Western culture, were clinically effective, but were presented without some of the traditional Buddhist teachings. Furthermore, they suggested that including additional “meditative practices and principles (e.g., ethical awareness, impermanence, emptiness/non-self, loving kindness, and compassion meditation, . . .)” (p. 592) may make these interventions even more effective. The MBPBS program includes several components, such as the Brahmavihara—the Four Immeasurables (i.e., loving kindness [metta], compassion [karuna], empathetic joy [mudita], and equanimity [upekkha]) and explicit teachings on ethical precepts that place it within the second-generation of mindfulness-based interventions. Whether MBPBS is equally beneficial for caregivers with and without these additional components remains to be investigated in future research.

The present study adds to the growing evidence base for the effectiveness of MBPBS in attenuating caregiver stress, regardless of whether the caregivers are paid staff, teachers, or parents of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Future research should investigate whether similar results are evidenced in caregivers of people with other needs, such as those with dementia, cancer, and other medical and psychiatric conditions. Furthermore, it is worth considering the impact of system-wide implementation of mindfulness-based interventions, such as MBPBS, that may change the life-course of not only the recipients of the training but also their clients because of the immeasurable downstream effects across generations. Another important consideration is the growing interest in integrated health care approaches that combine complementary and conventional treatments for disease prevention and health promotion (Khorsan et al. 2011). Mindfulness-based procedures offer a valuable addition to an integrated health care approach, especially for the management challenges associated with chronic conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Future research should investigate how best to integrate mindfulness-based interventions at different levels of care, including at the level of the caregiver, treatment team, executive management, and the health or mental health system.

Acknowledgments

A portion of the data included in this paper were first presented at the Second International Conference on Mindfulness (ICM-2), Sapienza University, Rome, Italy, May 11–15, 2016, and with additional data at the IASSIDD 4th Asia-Pacific Regional Congress: Inclusiveness and Sustainable Development, November 13–17, 2017, Bangkok, Thailand.

Funding

Preparation of this article was supported by a National 461 Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (NRF-2010-361- 462 A00008) funded by the Korean Government (MEST).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

NNS is the developer of the MBPBS program. The authors declare no conflict of interest and they do not work for, consult to, and own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Adams RE, Boscarino JA, Figley CR. Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: a validation study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(1):103–108. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D, James W, Evans J, Hawkins S, Jenkins R. Positive behavioural support: definition, current status and future directions. Tizard Learning Disability Review. 2005;10:4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JL, Albin RW, Mesaros RW, Dunlap G, Morelli-Robbins M. Issues in providing training to achieve comprehensive behavioral support. In: Reichle J, Wacker DP, editors. Communicative alternatives to challenging behavior: integrating functional assessment and intervention strategies. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 1993. pp. 363–406. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JL, Russo A, Dunlap G, Albin RW. A team training model for building the capacity to provide positive behavioral supports in inclusive settings. In: Koegel LK, Koegel RL, Dunlap G, editors. Positive behavioral support: including people with difficult behavior in the community. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 1996. pp. 467–490. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker JE, Julian J, Webber L, Chan J, Shawyer F, Meadows G. Evaluation of an occupational mindfulness program for staff employed in the disability sector in Australia. Mindfulness. 2013;4:122–136. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker JE, Webber L, Julian J, Shawyer F, Graham AL, Chan J, Meadows G. Mindfulness-based training shows promise in assisting staff to reduce their use of restrictive interventions in residential services. Mindfulness. 2014;5:598–603. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Williamson G. Psychological stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux JM, Hastings RP, Noone SJ. Staff stress and burnout in intellectual disability services: work stress theory and its application. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2009;22(6):561–573. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux JM, Hastings RP, Noone SJ, Firth A, Totsika V. Social support and coping as mediators or moderators of the impact of work stressors on burnout in intellectual disability support staff. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30(2):367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didden Robert, Lindsay William R., Lang Russell, Sigafoos Jeff, Deb Shoumitro, Wiersma Jan, Peters-Scheffer Nienke, Marschik Peter B., O’Reilly Mark F., Lancioni Giulio E. Evidence-Based Practices in Behavioral Health. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. Aggressive Behavior; pp. 727–750. [Google Scholar]

- Donnchadha SO. Stress in caregivers of individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities: a systematic review of mindfulness-based interventions. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jar12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, Heineman M, Knoster T, Fox L, Anderson JL, Albin RW. Essential elements of in-service training in positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Intervention. 2000;2(1):22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Epp K. Burnout in critical care nurses: a literature review. Dynamics (Pembroke, Ont.) 2012;23(4):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmell AL, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, Mausbach BT. A review of the psychobiology of dementia caregiving: a focus on resilience factors. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011;13(3):219–224. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Horne S. Positive perceptions held by support staff in community mental retardation services. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2004;109(1):53–62. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<53:PPHBSS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Horne S, Mitchell G. Burnout in direct care staff in intellectual disability services: a factor analytic study of the Maslach burnout inventory. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2004;48:268–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton C, Emerson E, Rivers M, Mason H, Mason L, Swarbrick R, Kiernan C, Reeves D, Alborz A. Factors associated with staff stress and work satisfaction in services for people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1999;43(4):253–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1999.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieneman M, Fefer SA. Employing the principles of positive behavior support to enhance family education and intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2017;26(10):2655–2668. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are. New York, NY: Hyperion; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Khorsan Raheleh, Coulter Ian D., Crawford Cindy, Hsiao An-Fu. Systematic Review of Integrative Health Care Research: Randomized Control Trials, Clinical Controlled Trials, and Meta-Analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2011/636134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoni M, Corti S, Cavagnola R, Healy O, Noone SJ. How acceptance and commitment therapy changed the perspective on support provision for staff working with intellectual disability. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities. 2016;10(1):59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lin JD, Lee TN, Yen CF, Loh CH, Hsu SW, Wu JL, et al. Job strain and determinants in staff working in institutions for people with intellectual disabilities in Taiwan: a test of the job demand-control-support model. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30(1):146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucyshyn, J. M., Dunlap, G., & Freeman, R. (2015). A historical perspective on the evolution of positive behavior support as a science-based discipline. In F. Brown, J. L. Anderson, & R. L. De Pry (2015). Individual positive behavior supports: a standards-based guide to practices in school and community settings (pp. 3-25). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- MacDonald A. Staff training in positive behavior support. In: Singh NN, editor. Handbook of evidence-based practices for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. New York: Springer; 2016. pp. 443–466. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52(1):397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev ON, Krägeloh CU, Hill EM, Billington R, Siegert RJ, Webster CS, et al. Rasch analysis of the Perceived Stress Scale: transformation from an ordinal to a linear measure. Journal of Health Psychology. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1359105316689603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed S, Shirom A, Toker S, Berliner S, Shapira I. Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(3):327–353. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris KR, Horner RH. Positive behavior support. In: Singh NN, editor. Handbook of evidence-based practices for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. New York: Springer; 2016. pp. 415–441. [Google Scholar]

- Noone SJ, Hastings RP. Building psychological resilience in support staff caring for people with intellectual disabilities: pilot evaluation of an acceptance-based intervention. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2009;13:43–53. doi: 10.1177/1744629509103519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noone SJ, Hastings RP. Using acceptance and mindfulness-based workshops with support staff caring for adults with intellectual disabilities. Mindfulness. 2010;1:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Piko B. Worker-related stress among nurses: a challenge for health care institutions. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 1999;119(3):156–162. doi: 10.1177/146642409911900304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenot JP, Rigaud JP, Prin S, Barbar S, Pavon A, Hamet M, Moutel G. Suffering among carers working in critical care can be reduced by an intensive communication strategy on end-of-life practice. Intensive Care Medicine. 2012;38:55–61. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2413-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J, Jones F, Fletcher B. Investigating the relationship between stress and worker behavior. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1998;42(2):163–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli WB, Buunk BP. Burnout: an overview of 25 years of research and theorizing. In: Schabracq MJ, Winnubst JAM, Cooper CL, editors. The handbook of work and health psychology. 2. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2003. pp. 383–424. [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton ASW, Singh AN, Adkins AD, Singh J. Mindful staff can reduce the use of physical restraints when providing care to individuals with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2009;22:194–202. [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton ASW, Karazsia BT, Singh J. Mindfulness training for teachers changes the behavior of their preschool students. Research in Human Development. 2013;10(3):211–233. [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton ASW, Karazsia BT, Myers RE, Latham LL, Singh J. Mindfulness-Based Positive Behavior Support (MBPBS) for mothers of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: effects on adolescents’ behavior and parental stress. Mindfulness. 2014;5:646–657. [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Karazsia BT, Myers RE, Winton ASW, Latham LL, Nugent K. Effects of training staff in MBPBS on the use of physical restraints, staff stress and turnover, staff and peer injuries, and cost effectiveness in developmental disabilities. Mindfulness. 2015;6:926–937. [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Manikam R, Latham LL, Jackman MM. Mindfulness-based positive behavior support in intellectual and developmental disabilities. In: Ivtzan I, Lomas T, editors. Mindfulness in positive psychology: the science of meditation and wellbeing. East Sussex, UK: Taylor & Francis; 2016. pp. 212–226. [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Karazsia BT, Myers RE. Caregiver training in Mindfulness-Based Positive Behavior Supports (MBPBS): effects on caregivers and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7:98. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Karazsia BT, Chan J, Winton ASW. Effectiveness of caregiver training in mindfulness-based positive behavior support (MBPBS) vs. training-as-usual (TAU): a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7:1549. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirrow P, Hatton C. Burnout amongst direct care workers in services for adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review of research findings and initial normative data. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2007;20(2):131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm BH. The concise ProQOL manual. 2. Pocatello, ID: ProQOL.org; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gordon W, Shonin E, Griffiths MD. Towards a second generation of mindfulness-based interventions. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;49(7):591–592. doi: 10.1177/0004867415577437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C, Holland E, Marsland D, Oakes P. The identification of environments and cultures that promote the abuse of people with intellectual disabilities: a review of the literature. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2003;16(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]