Abstract

Background

Bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), particularly methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), are challenging to treat and are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Telavancin is a lipoglycopeptide antibacterial active against susceptible Gram-positive pathogens, including MRSA.

Objective

This registry study assessed the real-world use and clinical outcomes of telavancin in patients with bacteremia or endocarditis enrolled in the Telavancin Observation Use Registry (TOUR™).

Methods

The subset of patients enrolled in TOUR who were diagnosed with endocarditis and/or bacteremia with a known or unknown primary source (N = 151) were analyzed. Data including demographics, infection type, baseline pathogens, prior or concomitant antimicrobial therapy, dosing regimen, clinical response, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) of interest, and mortality were collected by retrospective medical chart review.

Results

Telavancin was primarily used as a second-line or greater therapy (n = 132, 87.4%). MRSA was present in 87 (57.6%) patients. Median telavancin dose was 740.6 mg (interquartile range (IQR) 206.0 mg) and median duration of therapy was 9.0 days (IQR 24.0 days). Of the 132/151 (87.4%) patients with an available assessment at the end of telavancin therapy, a positive clinical response was achieved in 98/132 (74.2%), while 14/132 (10.6%) failed therapy and 20/132 (15.2%) had an indeterminant outcome. TEAEs occurred in 24 (15.9%) patients. The most frequent TEAE was renal failure (n = 12, 7.9%); seven of these patients were receiving concomitant nephrotoxic medications. There was no change in creatinine clearance for 67/89 (75.3%) patients with values recorded at the beginning and the end of telavancin therapy.

Conclusions

In real-world clinical practice, overall positive clinical outcomes are observed in patients with bacteremia or endocarditis treated with telavancin, including in those patients infected with MRSA or another S. aureus pathogen. Telavancin may be an alternative treatment option for these patients.

Trial Registration

This trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02288234) on 11 November 2014.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40801-020-00191-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points

| A subanalysis of the Telavancin Observational Use Registry (TOUR™), a registry of characteristics and outcomes of telavancin use in clinical practice, examined treatment of patients with bacteremia or endocarditis. |

| This subanalysis suggests telavancin is a promising and viable option for patients with bacteremia or endocarditis, including those with MRSA or another S. aureus pathogen. |

Background

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a leading cause of bacteremia and the most common cause of infective endocarditis in industrialized countries [1, 2]. S. aureus bacteremia is associated with severe complications including infective endocarditis, osteoarticular infections, and septic shock that ultimately result in increased patient mortality [3–5]. Additionally, involvement of resistant bacterial strains, such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), make S. aureus bacteremia challenging to treat [6]. Vancomycin and daptomycin are the recommended first-line therapies for MRSA bacteremia and infective endocarditis [7]; however, alternative therapies may be needed for strains with reduced susceptibility or resistance to antibacterial agents, potential toxicities, and even general lack of efficacy in certain patient populations. Different therapies are also necessary for treatment of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) bacteremia especially regarding patients with beta-lactam allergies [8–10]. Moreover, daptomycin is inactivated by pulmonary surfactants and is unsuitable for bacteremic patients with a respiratory focus of infection [11]. Current clinical and microbiologic treatments for bacteremia are far from ideal in terms of the time to effective therapy, pathogen-susceptibility, and specificity [4, 12]. Owing to the considerable mortality associated with S. aureus bacteremia [4, 6], there is a need to identify more efficacious alternative agents.

Telavancin is a lipoglycopeptide antibacterial active against susceptible Gram-positive pathogens, including MSSA and MRSA, that is administered intravenously once daily (or every 48 h with renal impairment), and is suitable for both inpatient and outpatient use [13–15]. Telavancin has demonstrated efficacy in patients with either complicated skin and skin-structure infections (cSSSI) or hospital-acquired bacterial and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (HABP/VABP) with concurrent S. aureus bacteremia [16]. In in vitro studies, a global collection of unique S. aureus strains causing bacteremia—including endocarditis, MSSA, and MRSA, multidrug-resistant strains and those with a high vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)—were 100% susceptible to telavancin [17].

While telavancin is not approved for treatment of patients with bacteremia or endocarditis, previous randomized clinical trials of telavancin compared to standard therapy have included patients with S. aureus bacteremia [14–16, 18]. The phase 2 ASSURE trial enrolled 60 patients with uncomplicated S. aureus bacteremia and provided the proof-of-concept for telavancin therapy for this infection, as the cure rate of the clinically evaluable population was similar to that of standard therapy (88% vs. 89%) [18]. A post hoc analysis of 105 patients with bacteremia concurrent to HABP/VABP or cSSSI from the pivotal phase 3 trials for telavancin versus vancomycin supported the efficacy of telavancin in patients with bacteremia with a known infection source (cure rate of telavancin vs. vancomycin: cSSSI, 57.1% vs. 54.5%; HABP/VABP, 54.3% vs. 47.4%) [13, 16].

In the USA, telavancin 10 mg/kg body weight delivered intravenously once daily is approved in adults for the treatment of cSSSI due to susceptible Gram-positive pathogens, and for HABP/VABP caused by susceptible isolates of S. aureus when alternative treatments are not suitable [13]. The Telavancin Observational Use Registry (TOUR™) was a multicenter observational registry study designed to characterize real-world population characteristics and clinical outcomes associated with telavancin use for Gram-positive infections [19]. Here, we present patient characteristics, telavancin dosing, and clinical outcomes of patients with bacteremia and/or endocarditis from TOUR.

Methods

Study Design, Data Collection, and Data Analysis

The implementation of TOUR has been described previously [19]. All patients in the registry diagnosed by their treating physician with endocarditis or bacteremia with or without a known primary source were included in the presented analysis. All treatment decisions and clinical assessments were at the treating physician’s discretion and not mandated by registry study design or protocol. Retrospectively collected data included—but was not limited to—demographics, infection type, baseline pathogens, prior or concomitant antimicrobial therapy, telavancin dosing regimen, clinical response, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) of interest, and mortality.

Patients with missing or undocumented outcome at the end of telavancin therapy (EOTT; last dose of telavancin) were excluded from the clinical outcome analysis. Clinical response was designated as positive, failed, or indeterminate. Positive responses included patients who were cured (resolution of signs and symptoms, no longer needing antibacterial therapy, or negative culture) or who showed partial response to telavancin and/or continued to require antibacterial therapy. Failure was defined as: a positive culture at EOTT; inadequate response to telavancin therapy; resistant, worsening, new, or recurrent signs and symptoms; or required change of antibacterial prior to the planned duration of telavancin therapy. Clinical outcome was labeled indeterminate if there was insufficient information at the assessment to determine a positive or failed response.

Adverse event (AE) data collection was limited to renal AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation or a fatal outcome. AEs were reported at the discretion of the investigator; capturing AEs of interest was prioritized and there was no mandate to report all AEs. Renal function was evaluated through serum creatinine concentration values obtained up to 15 days prior to telavancin therapy and at EOTT; any values collected at the time of or after a subject started on hemodialysis were excluded from the renal function analysis. Potentially nephrotoxic concomitant medications taken 2 days prior to initiation of telavancin therapy to 2 days after EOTT were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

No formal hypothesis or statistical significance testing was planned. All analyses were descriptive and performed using SAS® version 9.2 or higher (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Creatinine clearance was estimated using the Cockcroft-Gault equation with actual body weight [20]. The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®), version 17.1, was used to code TEAE and medical history terms recorded in the electronic case report forms while concomitant medications were coded according to the World Health Organization Drug Dictionary, September 2014. MedDRA terminology is the international medical terminology developed under the auspices of the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. MedDRA® trademark is owned by International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA) on behalf of ICH.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of the 1063 patients enrolled in TOUR, 151 were diagnosed with endocarditis, bacteremia of an unknown source, or bacteremia with the following sources: cSSSI, lower respiratory tract infection, or bone and joint infection (Table 1). Clinical response at EOTT was available for 132/151 (87.4%) patients; 21/151 (13.9%) patients died ≤ 28 days after starting telavancin treatment. Only two of the deaths were considered possibly related to telavancin by investigators. Of these 151 patients, 54.3% were male, 64.2% were < 65 years of age, and 77.5% were White. Median body mass index was 27.3 kg/m2 (mean 28.70 ± 8 0.47) and most had at least one co-morbidity (n = 146; 96.7%), primarily hypertension (46.4%) or type 2 diabetes mellitus (30.5%) (Table 2). At baseline, 13 (8.6%) patients were on dialysis, including intermittent hemodialysis (n = 8; 5.3%) and continuous renal replacement therapy (n = 4; 2.6%). Baseline serum creatinine concentration was within the normal range (0.55–1.18 mg/dL) [21] for 50% of patients with a serum creatinine concentration measurement [n = 111; median 0.8 mg/dL, interquartile range (IQR) 0.5 mg/dL], and the baseline median estimated creatinine clearance (CrCl) was 108.5 mL/min (n = 110) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline infections of the TOUR subpopulation included in this analysis (N = 151)

| Infection type | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Bacteremia of unknown primary source | 93 (61.6) |

| Endocarditis | 13 (8.6) |

| Bacteremia with known primary source | 45 (29.8) |

| cSSSI | |

| Abscess | 7 (4.6) |

| Cellulitis | 4 (2.6) |

| Surgical wound | 3 (2.0) |

| Burn | 1 (0.7) |

| Lower respiratory infections | |

| HABP | 4 (2.6) |

| Other pneumonia | 3 (2.0) |

| CAP | 1 (0.7) |

| Lung abscess | 1 (0.7) |

| VABP | 1 (0.7) |

| Bone and joint infections | |

| Osteomyelitis without prosthetic material | 13 (8.6) |

| Acute septic arthritis | 3 (2.0) |

| Prosthetic joint infection | 1 (0.7) |

| Othera | 3 (2.0) |

CAP community-acquired pneumonia, cSSSI complicated skin and skin-structure infections, HABP hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia, VABP ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia

aOther includes 2 subjects with sepsis and 1 subject with infected grafts after aortofemoral bypass

Table 2.

Patient characteristics (N = 151)

| Characteristic | n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Age (years)b | |

| Mean (SD) | 55.3 (18.3) |

| Median (range) | 58.5 (71) |

| Age distribution | |

| < 65 years | 97 (64.2) |

| ≥ 65 years | 54 (35.8) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 82 (54.3) |

| Female | 69 (45.7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Not hispanic or latino | 138 (91.4) |

| Hispanic or latino | 6 (4.0) |

| Unknown | 4 (2.6) |

| Not reported | 3 (2.0) |

| Race | |

| White | 117 (77.5) |

| Black or African American | 21 (13.9) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 (2.6) |

| Asian | 1 (0.7) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 |

| Other | 8 (5.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Mean (SD) | 28.7 (8.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 27.3 (9.6) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | |

| n | 111 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.5) |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | |

| n | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 126.1 (89.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 108.5 (96) |

| Common comorbiditiesc | |

| Hypertension | 70 (46.4) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 46 (30.5) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 24 (15.9) |

| Drug abuser | 22 (14.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 21 (13.9) |

| Renal failure, chronic | 21 (13.9) |

| Myocardial infarction | 19 (12.6) |

| Cardiac failure, congestive | 17 (11.3) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 17 (11.3) |

| Hepatitis C | 16 (10.6) |

BMI body mass index, IQR interquartile range, SD standard deviation

aUnless otherwise noted

bFor 1 patient, age was reported only as ≥ 90 years old

cComorbidities that occurred in ≥ 10% of patients

Care Setting and Utilization

At initiation of telavancin therapy, the majority of patients received treatment in an inpatient setting—89 (58.9%) at a hospital ward and 32 (21.2%) in an intensive care unit. Patients spent a median (range) of 12.0 (2.0–94.0) days in a hospital ward (n = 88; not recorded for one patient) and 9.0 (1.0–123.0) days in the intensive care unit (n = 32). Of the 151 patients with bacteremia or endocarditis, 115 (76.1%) had an available measurement for time to discharge. Median time to discharge after telavancin initiation was 8 days (range 1–100 days). Initiation of telavancin therapy occurred in an outpatient infusion center for 18/151 patients (11.9%), outpatient clinics for 7/151 (4.6%) patients, or other facility for 5/151 (3.3%) patients.

Baseline Pathogens

Infecting pathogens were identified in 148 (98.0%) patients at baseline. Telavancin-spectrum pathogens, especially Staphylococcus species, were the most common. MRSA was present in 87 (57.6%) patients (Table 3). Vancomycin MIC, as determined by site-specific testing methods for MRSA, was ≥ 1 µg/mL for 41 of 43 patients with an available vancomycin MIC. Telavancin MIC was not collected in these patients, and vancomycin MIC was only collected when included as the standard of care at the respective center. Multiple infecting pathogens were identified in 19 (12.6%) patients; 18 (11.9%) with two identified pathogens and one (0.7%) with three identified pathogens. Mixed infection, the presence of both a Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogen, was identified in ten (6.6%) patients, and nine (6.0%) patients were infected with multiple Gram-positive pathogens.

Table 3.

Pathogens identified at baseline in > 1% of patients (N = 151)

| Infecting pathogen | n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Telavancin-spectrum | |

| Staphylococcus spp. | |

| MRSA | 87 (57.6) |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus | 23 (15.2) |

| MSSA | 21 (13.9) |

| Enterococcus spp. | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 4 (2.6) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 3 (2.0) |

| Streptococcus spp. | |

| Streptococcus anginosus group | 2 (1.3) |

| Streptococcus mitis/Streptococcus oralis | 2 (1.3) |

| Other Gram-positive | |

| Gram-positive cocci | 2 (1.3) |

| Viridans streptococci | 2 (1.3) |

| Gram-negative | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 4 (2.6) |

| Escherichia coli | 3 (2.0) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 3 (2.0) |

| Serratia marcescens | 3 (2.0) |

MRSA methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MSSA methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, MRSE Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis, spp. species, VISA vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus, VRE vancomycin-resistant enterococci

aNote that the sum of this column will exceed 151 because some patients were infected with more than 1 pathogen

Prescribing Patterns

Telavancin was primarily prescribed as a second-line or greater therapy (n = 132; 87.4%). Prior to telavancin therapy, 136 patients received common antibacterial agents active against Gram-positive pathogens; 87/136 (64.0%) patients received vancomycin, 37/136 (27.2%) daptomycin, 13/136 (9.6%) ceftaroline, 8/136 (5.9%) linezolid, and 1/136 (0.7%) sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim, among others. Of the 13 patients who discontinued telavancin therapy and had a post-telavancin Gram-positive antibacterial therapy recorded, 1/13 (7.7%) was placed on vancomycin, 3/13 (23.1%) on daptomycin, 3/13 (23.1%) on ceftaroline, 2/13 (15.4%) on sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and 1/13 (7.7%) on linezolid, among others. Of the 151 subjects included, 84 (55.6%) discontinued due to clinical cure, eight (5.3%) due to clinical failure, 22 (14.6%) due to adverse events (unspecified), six (4.0%) were lost to follow-up, and 31 (20.5%) were marked as other reasons.

The approved dose regimen for telavancin for patients with normal renal function (CrCl > 50 mL/min) is 10 mg/kg body weight infused intravenously every 24 h. A dosage adjustment is required for patients with renal impairment. Patients with CrCl 30 to < 50 mL/min should receive 7.5 mg/kg every 24 h, and those with CrCl 10 to < 30 mL/min should receive 10 mg/kg every 48 h [13]. Mean average daily dose of telavancin in patients with bacteremia or endocarditis in this registry was 688.5 ± 207.6 mg (median 740.6, IQR 206.0); and by body weight was 8.4 ± 2.3 mg/kg (median 8.7, IQR 2.8) (Table 4). Most patients remained on their starting dose; doses were not adjusted for 129 (85.4%) patients. The dose of telavancin administered to this subset of TOUR patients with bacteremia and endocarditis was lower than the recommended levels for patients with CrCl > 50 mL/min and greater for patients with CrCl 30 to < 50 mL/min or < 30 mL/min (Table 4).

Table 4.

Telavancin dosing and duration of therapy by patient baseline renal function

| Telavancin exposure characteristics | Dialysis (n = 13) | Baseline CrCl (mL/min)a | Total (N = 151) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 30 (n = 5) | 30 to < 50 (n = 10) | 50 to < 80 (n = 18) | ≥ 80 (n = 77) | |||

| Average daily dose (mg)b | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 465.9 (235.5) | 601.6 (291.0) | 617.6 (114.9) | 641.0 (161.1) | 748.8 (186.0) | 688.5 (207.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 422.7 (215.1) | 625.0 (409.8) | 650.0 (201.6) | 600.0 (207.7) | 750.0 (80.0) | 740.6 (206.0) |

| Duration of therapy (days) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 24.4 (20.5) | 16.8 (18.6) | 17.0 (18.3) | 8.4 (10.6) | 13.4 (13.5) | 17.2 (16.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 17.0 (30.0) | 12.0 (4.0) | 6.0 (28.0) | 5.0 (6.0) | 8.0 (12.0) | 9.0 (24.0) |

| Average daily dose per body weight (mg/kg) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.5) | 7.3 (2.9) | 8.4 (2.3) | 8.9 (1.5) | 9.1 (1.8) | 8.4 (2.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.4 (3.2) | 6.0 (4.0) | 8.1 (2.9) | 7.8 (6.5) | 9.3 (2.4) | 8.7 (2.8) |

| Telavancin dose adjustedc | ||||||

| n (%) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (22.2) | 10 (13.0) | 22 (14.6) |

CrCl creatinine clearance, IQR interquartile range, SD standard deviation

aBaseline CrCl was not estimated for 27 patients because the baseline serum creatinine concentration was not recorded, and for 1 patient due to missing age

bAverage daily dose per body weight was calculated to account for different dosing schedules. 139 patients were dosed every 24 h, 8 were dosed every 48 h, and 4 were dosed at a frequency recorded as “other.”

cPatients whose dose changed from the initial recorded dose

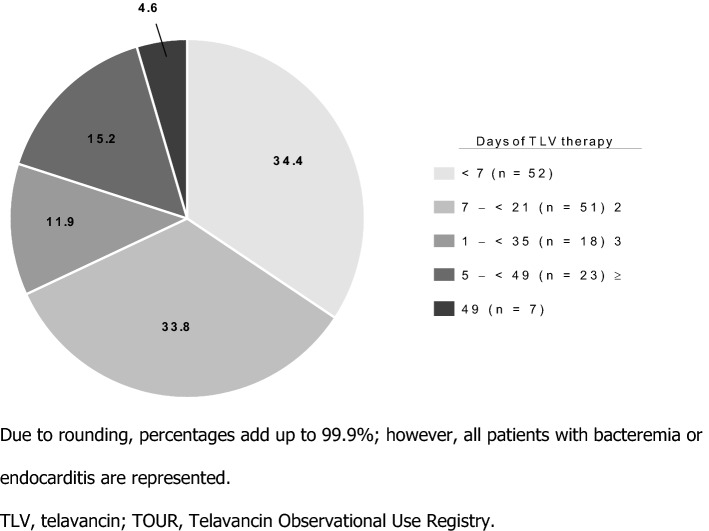

Median telavancin therapy duration was 9.0 days (IQR 24), ranging from 1–70 days (Table 4). Approximately one-third of patients received telavancin for < 7 days, one-third for 7 to < 21 days, and the last third for 21 to ≥ 49 days (Fig. 1). Average duration of treatment for subjects with a failed outcome at the end of telavancin therapy (n = 14) was 10.6 ± 7.7 days (median 8 days, IQR 9.0) and average daily dose was 635.82 ± 203.68 (median 652.50 mg, IQR 250). Those with a positive outcome at the end of telavancin treatment (n = 98) had a mean duration of treatment of 20.6 ± 17.8 days (median 13.5 days, IQR 31) and a mean daily dose of 686.55 ± 22.092 mg (median 735.55 mg, IQR 240).

Fig. 1.

Duration of therapy in TOUR patients with bacteremia or endocarditis (N = 151). Due to rounding, percentages add up to 99.9%; however, all patients with bacteremia or endocarditis are represented. TLV telavancin, TOUR telavancin observational use registry

Clinical Response

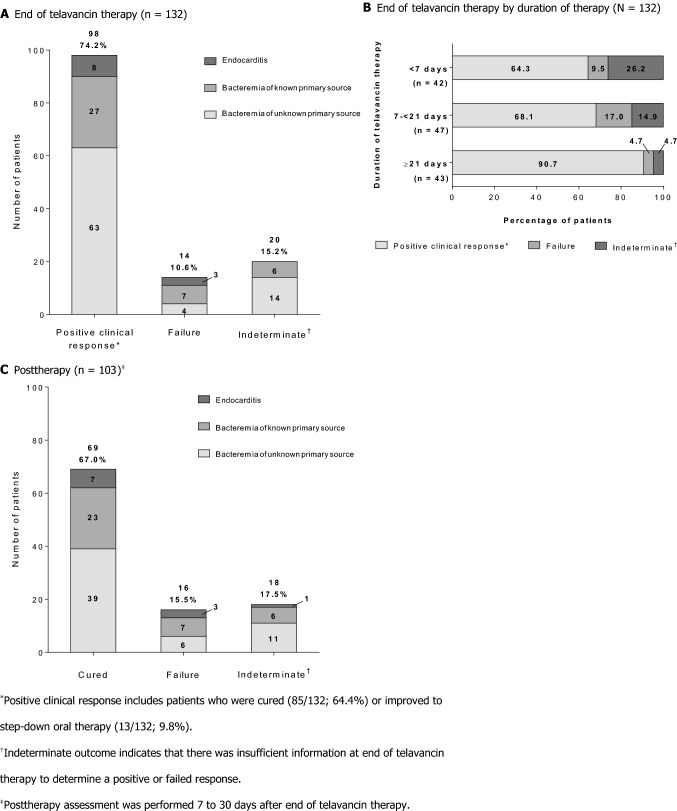

Clinical response at EOTT was available for 132 of the 151 patients with bacteremia or endocarditis in TOUR. Other recorded clinical outcomes in patients with missing or undocumented EOTT assessments are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Positive clinical response was achieved in 98/132 (74.2%) patients; 14/132 (10.6%) failed telavancin therapy, and 20/132 (15.2%) were indeterminate. Similar trends were observed for each infection type: endocarditis, bacteremia of unknown primary source, or bacteremia with known primary source (Fig. 2a). The majority of patients with a positive response at EOTT were cured (endocarditis 7/8, 87.5%; bacteremia with unknown primary source 59/63, 93.7%; bacteremia with known primary source 19/27, 70.4%); the remaining patients achieved a positive response and were stepped down to oral therapy (13/132, 9.8%; two cephalexin, one sulfamethoxazole with trimethoprim, one cefazolin, one linezolid, and eight not recorded). Patients with positive clinical responses at EOTT had a longer duration of therapy (mean 20.6 ± 17.8 days, median 13.5 days, IQR 31) and a higher dose of telavancin (average daily dose 685.55 ± 22.092, median 735.55 mg (8.7 mg/kg), IQR 240) compared with patients who failed telavancin therapy. Average duration of treatment for subjects with a failed outcome at the end of telavancin therapy was 10.6 ± 7.7 days (median 8 days, IQR 9.0) and average daily dose was 635.82 ± 203.68 (median 652.50 mg (7.6 mg/kg), IQR 250). Clinical response at EOTT by duration of telavancin therapy is presented in Fig. 2b. Outcomes at post-therapy assessment (7–30 days after EOTT) by infection type are presented in Fig. 2c. Post-therapy assessment was available for 103 patients; 69/103 (67.0%) were cured, 16/103 (15.5%) failed therapy, and 18/103 (17.5%) were indeterminate. The 16 subject failures from the post-therapy assessment do not necessarily represent relapses, but rather include patients previously classified as an indeterminate status or who had improved to step-down therapy.

Fig. 2.

Clinical outcomes for patients with available assessments. Asterisk: Positive clinical response includes patients who were cured (85/132; 64.4%) or improved to step-down oral therapy (13/132; 9.8%). Dagger: Indeterminate outcome indicates that there was insufficient information at end of telavancin therapy to determine a positive or failed response. Double dagger: Post-therapy assessment was performed 7–30 days after end of telavancin therapy

Safety

TEAEs of interest occurred in 24 (15.9%) patients; 19 (12.6%) experienced a serious TEAE and 16 (10.6%) discontinued telavancin therapy due to a TEAE. For 13 (8.6% of all subjects and 54% of all TEAEs) patients, a TEAE was considered possibly related to telavancin therapy. A total of 21 (13.9%) patients died during the registry study, which mostly are assumed to be due to the underlying disease but causality cannot be confirmed; this included 16 fatal outcomes due to a TEAE (10.6% of all subjects and 76% of deaths) and other deaths that occurred during the 28-day mortality assessment. Detailed information for the most frequent TEAEs is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Treatment-emergent adverse events in ≥ 1% of patients (N = 151)

| MedDRA preferred term | Frequency | Serious | Possibly related to treatment | Discontinued treatmenta | Resolvedb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal failurec | 12 (7.9) | 7 (4.6) | 11 (7.3) | 7 (4.6) | 6 (4.0) |

| Cardiac arrest | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.0) | 0 |

| Respiratory failure | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) | 0 | 3 (2.0) | 0 |

| Sepsis | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.0) | 0 |

Data presented as n (%)

MedDRA medical dictionary of regulatory activities, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

aDiscontinued treatment includes those patients who had drug withdrawn or withdrew from the study

bResolved includes those events that were Recovered/Resolved, Recovered/Resolved with Sequelae, or Recovering/Resolving

cIncludes TEAEs reported as MedDRA terms “renal failure” or “renal failure acute”

Renal TEAEs occurred in 12 patients with bacteremia or endocarditis (7.9%), which represents half of all patients who reported TEAEs in this subpopulation. Five of these 12 patients (41.7%) discontinued telavancin therapy, 1/12 (8.3%) had a fatal outcome, and 6/12 (50%) resolved (Table 5). Change in serum creatinine concentration from baseline for patients with renal TEAEs is shown in Table 6. Of the 12 patients who had a renal TEAE, seven were taking concomitant nephrotoxic medications. Of all 151 patients, 71 (47.0%) received nephrotoxic medications concomitantly with telavancin. The most frequent (≥ 10%) nephrotoxic concomitant medications included sulfonamides (35.2%), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (23.9%), vancomycin (18.3%), ketorolac (16.9%), IV contrast/radiocontrast media/dye (16.9%), ibuprofen/naproxen (14.1%), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (14.1%), and acetylsalicylic acid (12.7%).

Table 6.

Change in serum creatinine for patients who experienced a renal failure AE (n = 8)

| Patient | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | Days elapsed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Last recorded value | Increase from baseline | ||

| 1 | 1.1 | 11.1 | 10 | 33 |

| 2 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 49 |

| 3 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 15 |

| 4 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 15 |

| 5 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 12 |

| 6 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 11 |

| 7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 45 |

| 8 | 1.7 | 5.8 | 4.1 | 13 |

Of 12 patients with bacteremia or endocarditis who experienced renal failure during telavancin therapy, two did not have CrCl measurements recorded as they were on dialysis at baseline and two were missing a baseline serum creatinine concentration

AE adverse event, CrCL creatinine clearance

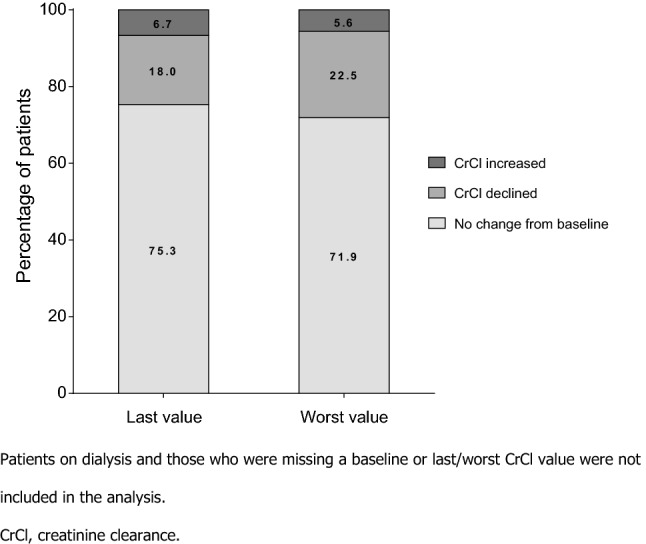

To reveal subtle changes in renal function that may not rise to the level of an AE, serum creatinine (SCr) measurements at baseline, last value on telavancin, and worst SCr value on telavancin were analyzed for 89 patients who had a baseline and second SCr value reported. The mean SCr at baseline (n = 111) was 1.03 ± 0.795 mg/dL (median 0.80). The mean change in SCr from baseline to the last value collected in telavancin treatment was an increase of 0.10 ± 0.481 mg/dL (median 0.00). The mean change in SCr from baseline to the worst (highest) value on telavancin treatment was an increase of 0.22 ± 0.522 (median 0.10.) The mean CrCl was 126.10 ± 89.65 (median 108.52) at baseline, 114.71 ± 83.43 (median 107.14) at last value, and 106.95 ± 79.56 (median 97.94) at lowest value. Furthermore, the mean change in CrCl from baseline to last available value was − 10.02 ± 57.01 (median 0.00). The mean change from worst value on treatment (n = 89) was − 19.04 ± 47.07 (median − 9.79). Moreover, most patients exhibited no change in CrCl category from baseline to their last or lowest value (last value 67/89, 75.3%; lowest value 64/89, 71.9%). CrCl category declined from baseline to their last or lowest value (last value 16/89, 18.0%; lowest value 20/89, 22.5%) or increased from baseline to their last or lowest value (last value 6/89, 6.7%; lowest value 5/89, 5.6%) in a minority of patients (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Summary of change in creatinine clearance from baseline to last and worst value during telavancin therapy (n = 89). Patients on dialysis and those who were missing a baseline or last/worst CrCl value were not included in the analysis. CrCl creatinine clearance

Discussion

In contrast to controlled trials, observational patient registries provide insight into real-world medical practice, shedding light on treatment patterns and important clinical outcomes that may not have been shown in clinical trials. The TOUR observational registry study included patients with bacteremia of an unknown primary source, bacteremia with a known primary source, and endocarditis—an infection that has been infrequently observed in or excluded from previous telavancin trials [14–16, 18] and reported in a few telavancin case reports [22–26]; this was the third largest infection group to receive telavancin in TOUR (151/1063, 14.2%), following cSSSI (518/1063, 48.7%) and bone and joint infections (291/1063, 27.4%) [19]. Cases of endocarditis treated with telavancin found in the literature were all MRSA cases, and most were initially treated with vancomycin. In one publication that reviewed most of the published cases identified, it was noted that bacteremia cleared after initiation of telavancin (median of 1 day later, range 1–3) in 9/15 cases with bacteremia already cleared before telavancin initiation in the remaining six cases [22]. Notably, side effects were not reported during telavancin therapy in these reviewed cases [22–26]. TOUR investigators often dosed patients with bacteremia and/or endocarditis with an average daily dose of telavancin different from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved dosages; this was also true for the overall TOUR population [19]. A positive clinical response, cured or improved to step-down oral therapy, was reported for the majority of patients with an available assessment at EOTT (74.2%; Fig. 2), with most patients cured at the post-treatment assessment (67.0% of those with an available assessment). These results further strengthen telavancin’s role in treatment of patients with Gram-positive bacteremia and/or endocarditis.

Duration of antibacterial therapy is a key factor in treatment of S. aureus bacteremia, with different treatment lengths recommended for patients who have complicated or uncomplicated bacteremia [3, 7, 27]. Though the best duration of therapy for uncomplicated S. aureus bacteremia is still debated, patients may receive treatment for 7–14 days for these infections [3, 28]. For complicated bacteremia (including endocarditis), 4–6 weeks of antibacterial therapy is recommended [3, 7, 28]. The designation of complicated or uncomplicated bacteremia was not recorded in TOUR. Furthermore, duration of therapy for patients with bacteremia or endocarditis was varied, with patients split nearly equally between < 7, 7–20, and ≥ 21 days of therapy. Interestingly, the positive clinical response rate at EOTT for patients who received ≥ 21 days of telavancin therapy was about 91%, as compared to about 66% of patients with shorter courses of therapy. This may suggest that longer courses of therapy could be beneficial for Gram-positive bacteremia or endocarditis; however, many other factors could have contributed to the differences in response rates.

In the pivotal phase 3 trials for telavancin in patients with HABP/VABP or cSSSI, occurrence of renal AEs was more likely in patients with existing kidney dysfunction or for those who were given concomitant nephrotoxic medications [13]. Based on the real-world data from TOUR, more than three-quarters of patients on telavancin with available CrCl measurements did not experience a decline in renal function. In TOUR, telavancin was often the second-line or greater therapy for bacteremia or endocarditis. This is not surprising as MRSA was the most frequent infecting pathogen and Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend vancomycin or daptomycin as first-line antibacterial agents for these infections [7]. Consequently, this practice may have selected patients with worse prognosis for enrollment in TOUR, affecting outcomes and safety analyses.

There are several limitations in this registry study, many inherent to the observational design. The decision to enroll a patient was made by the individual study clinicians, potentially introducing bias into patient selection at the start. Data collection by retrospective medical chart review restricted the available information for each patient. In addition, safety data collection in TOUR was not comprehensive, but instead focused on adverse events of interest including renal TEAEs and TEAEs leading to discontinuation or fatal outcome, which were reported at the discretion of the investigator. Renal function indicators were also not consistently collected. Additionally, the efficacy outcomes of this registry study were subjective, microbiology data were not collected systemically, and there was no differentiation between complicated and uncomplicated bacteremia. Finally, loss of patients to follow-up likely impacts the interpretation of the results. Despite these limitations, TOUR provides insight into telavancin use in US clinical practice to treat patients with bacteremia and endocarditis caused by challenging Gram-positive pathogens.

Conclusions

In real-world clinical practice with dosing at the investigator’s discretion, telavancin was frequently used with success as a second-line or greater therapy for patients with bacteremia or endocarditis who discontinued use of vancomycin or other antibacterial therapies. S. aureus species were the most common pathogens identified, with more than half of patients infected with MRSA. With the high morbidity and mortality rates associated with S. aureus bacteremia and endocarditis, it is important to provide more treatment options. These real-world data from TOUR suggest that telavancin may represent an alternative treatment option for patients with endocarditis, bacteremia of an unknown primary source, or bacteremia with a known source due to S. aureus or other Gram-positive bacteria.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the patients and investigators who were involved with TOUR, without whom this study would not have been possible. They would like to acknowledge Dr. Anna Osmukhina for her direction in the biostatistical analyses and intellectual contributions to the interpretation of data and thank Chris Barnes for his assistance with statistical analysis. Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Nicole Seneca, PhD, of AlphaBioCom, LLC, and Elizabeth Conrad, PhD, of Cumberland Pharmaceuticals, Inc, and funded by Theravance Biopharma R&D, Inc.

Author Contributions

All authors reviewed and revised each draft and read and approved the final manuscript. BC provided critical analysis of the data and was a major contributor. BF, KC, JR, and MJ were investigators who contributed patient data to TOUR and provided critical analysis of the data. DL performed the statistical analysis.

Funding

This study was funded by Theravance Biopharma R&D, Inc.

Availability of Data and Material

Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc. (and its affiliates) will not be sharing individual de-identified patient data or other relevant study documents.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

JR has served on advisory boards and speakers bureaus for Theravance Biopharma and Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc. MAJ has received payment for participating in speakers’ bureaus, advisory boards for Theravance Biopharma, Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc, and Allergan; payment for serving on speakers’ bureau for Merck & Co. (including former Cubist Pharmaceuticals); and received research support from Theravance Biopharma related to TOUR and from Allergan. BF has received payment for participating in speakers’ bureaus for Theravance Biopharma, Allergan, Melinta, Merck & Co., and La Jolla Pharmaceutical. KC has received payment for participating in speakers’ bureaus for Allergan, Merck & Co., Theravance Biopharma, and Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc; consulting fees for Theravance Biopharma; and grants from Theravance Biopharma for the collection of data were paid to Methodist Healthcare of Memphis. DL is an employee of Theravance Biopharma US, Inc. BC-R was an employee of Theravance Biopharma US, Inc. during the conduct of the study and owns stock in Theravance Biopharma, Inc.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The Copernicus Group Independent Review Board approved the TOUR observational study protocol on 29 December 2015. This was an observational use study with data collected via retrospective medical chart review, therefore signed informed consent from the patient was not required. Only de-identified information was collected in accordance with section 164.514 of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule.

Contributor Information

Joseph Reilly, Email: Joseph.Reilly@atlanticare.org.

Micah A. Jacobs, Email: Micjacobs@usa.net

Bruce Friedman, Email: brucefriedman.md@gmail.com.

Kerry O. Cleveland, Email: kclevel1@uthsc.edu

David A. Lombardi, Email: DLombardi@theravance.com

Bibiana Castaneda-Ruiz, Email: bibicast@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Fowler VG, Jr, Miro JM, Hoen B, Cabell CH, Abrutyn E, Rubinstein E, Corey GR, Spelman D, Bradley SF, Barsic B, et al. Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: a consequence of medical progress. JAMA. 2005;293(24):3012–3021. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.24.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laupland KB. Incidence of bloodstream infection: a review of population-based studies. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(6):492–500. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG., Jr Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Hal SJ, Jensen SO, Vaska VL, Espedido BA, Paterson DL, Gosbell IB. Predictors of mortality in Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(2):362–386. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05022-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner LM, Webb AK, Limbago B, Dudeck MA, Patel J, Kallen AJ, Edwards JR, Sievert DM. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011–2014. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(11):1288–1301. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen RV, Fowler VG, Jr, Skov R, Bruun NE. Future challenges and treatment of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia with emphasis on MRSA. Future Microbiol. 2011;6(1):43–56. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):285–292. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howden BP, Davies JK, Johnson PD, Stinear TP, Grayson ML. Reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, including vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains: resistance mechanisms, laboratory detection, and clinical implications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):99–139. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00042-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kullar R, Casapao AM, Davis SL, Levine DP, Zhao JJ, Crank CW, Segreti J, Sakoulas G, Cosgrove SE, Rybak MJ. A multicentre evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of high-dose daptomycin for the treatment of infective endocarditis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(12):2921–2926. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kullar R, Davis SL, Levine DP, Zhao JJ, Crank CW, Segreti J, Sakoulas G, Cosgrove SE, Rybak MJ. High-dose daptomycin for treatment of complicated gram-positive infections: a large, multicenter, retrospective study. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(6):527–536. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.6.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverman JA, Mortin LI, Vanpraagh AD, Li T, Alder J. Inhibition of daptomycin by pulmonary surfactant: in vitro modeling and clinical impact. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(12):2149–2152. doi: 10.1086/430352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul M, Kariv G, Goldberg E, Raskin M, Shaked H, Hazzan R, Samra Z, Paghis D, Bishara J, Leibovici L. Importance of appropriate empirical antibiotic therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(12):2658–2665. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.VIBATIV® (telavancin), USP [package insert]: Nashville: Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc. 2019.

- 14.Rubinstein E, Lalani T, Corey GR, Kanafani ZA, Nannini EC, Rocha MG, Rahav G, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, Shorr AF, et al. Telavancin versus vancomycin for hospital-acquired pneumonia due to gram-positive pathogens. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(1):31–40. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stryjewski ME, Graham DR, Wilson SE, O'Riordan W, Young D, Lentnek A, Ross DP, Fowler VG, Hopkins A, Friedland HD, et al. Telavancin versus vancomycin for the treatment of complicated skin and skin-structure infections caused by gram-positive organisms. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(11):1683–1693. doi: 10.1086/587896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson SE, Graham DR, Wang W, Bruss JB, Castaneda-Ruiz B. Telavancin in the treatment of concurrent Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a retrospective analysis of ATLAS and ATTAIN studies. Infect Dis Ther. 2017;6(3):413–422. doi: 10.1007/s40121-017-0162-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendes RE, Sader HS, Smart JI, Castanheira M, Flamm RK. Update of the activity of telavancin against a global collection of Staphylococcus aureus causing bacteremia, including endocarditis (2011–2014) Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36(6):1013–1017. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2865-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stryjewski ME, Lentnek A, O'Riordan W, Pullman J, Tambyah PA, Miro JM, Fowler VG, Jr, Barriere SL, Kitt MM, Corey GR. A randomized Phase 2 trial of telavancin versus standard therapy in patients with uncomplicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: the ASSURE study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:289. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bressler AM, Hassoun AA, Saravolatz LD, Ravenna V, Barnes CN, Castaneda-Ruiz B. Clinical experience with telavancin: real-world results from the telavancin observational use registry (TOUR™) Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(4):183–191. doi: 10.1007/s40801-019-00165-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ceriotti F, Boyd JC, Klein G, Henny J, Queralto J, Kairisto V, Panteghini M, Intervals ICoR, Decision L Reference intervals for serum creatinine concentrations: assessment of available data for global application. Clin Chem. 2008;54(3):559–566. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.099648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Majumdar R, Crum-Cianflone NF. Telavancin for MRSA endocarditis: case report and review of the literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2017;25(4):176–183. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcos LA, Camins BC. Successful treatment of vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus pacemaker lead infective endocarditis with telavancin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(12):5376–5378. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00857-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nace H, Lorber B. Successful treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis with telavancin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(6):1315–1316. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruggero MA, Peaper DR, Topal JE. Telavancin for refractory methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and infective endocarditis. Infect Dis (Lond) 2015;47(6):379–384. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2014.995696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson MM, Hassoun A. Successful salvage treatment of native valve Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis with telavancin: two case reports. Infect Dis (Lond) 2017;49(7):540–544. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2017.1300318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holland TL, Arnold C, Fowler VG., Jr Clinical management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a review. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, Craven DE, Flynn P, O'Grady NP, Raad II, Rijnders BJ, Sherertz RJ, Warren DK. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1–45. doi: 10.1086/599376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc. (and its affiliates) will not be sharing individual de-identified patient data or other relevant study documents.