Abstract

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a severe and frequently lethal disease caused by Ebola virus (EBOV). EVD outbreaks typically start from a single case of probable zoonotic transmission, followed by human-to-human transmission via direct contact or contact with infected bodily fluids or contaminated fomites. EVD has a high case–fatality rate; it is characterized by fever, gastrointestinal signs and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Diagnosis requires a combination of case definition and laboratory tests, typically real-time reverse transcription PCR to detect viral RNA or rapid diagnostic tests based on immunoassays to detect EBOV antigens. Recent advances in medical countermeasure research resulted in the recent approval of an EBOV-targeted vaccine by European and US regulatory agencies. The results of a randomized clinical trial of investigational therapeutics for EVD demonstrated survival benefits from two monoclonal antibody products targeting the EBOV membrane glycoprotein. New observations emerging from the unprecedented 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak (the largest in history) and the ongoing EVD outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo have substantially improved the understanding of EVD and viral persistence in survivors of EVD, resulting in new strategies toward prevention of infection and optimization of clinical management, acute illness outcomes and attendance to the clinical care needs of patients.

Subject terms: Ebola virus, Viral epidemiology, Viral pathogenesis, Public health, Immunization

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is caused by the filovirus Ebola virus (EBOV). Although the natural host of EBOV is undefined, a single zoonotic transmission is the probable start of most EVD outbreaks. EVD is characterized by gastrointestinal manifestations and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and has a high case–fatality rate.

Introduction

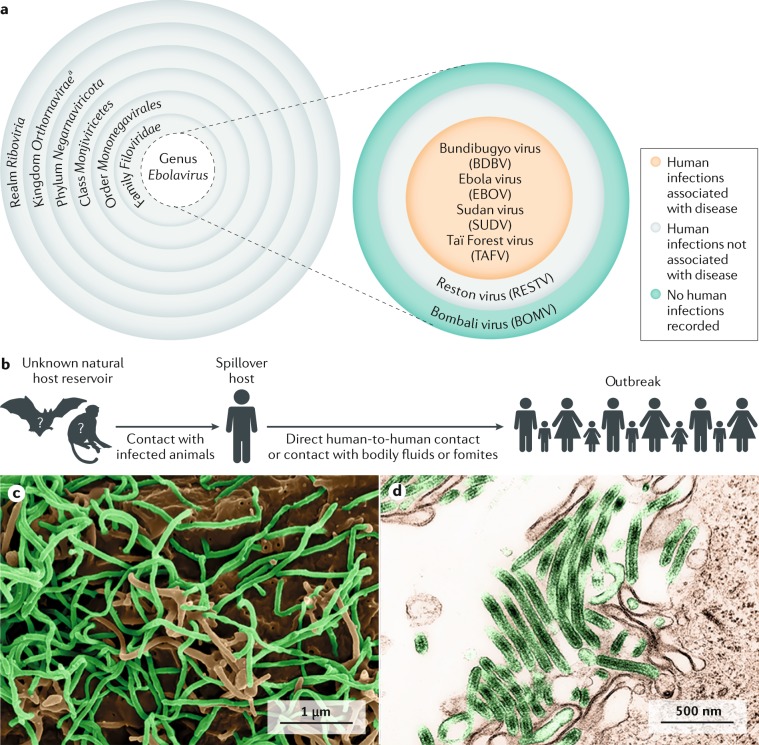

To date, 12 distinct filoviruses have been described1. The seven filoviruses that have been found in humans belong either to the genus Ebolavirus (Bundibugyo virus (BDBV), Ebola virus (EBOV), Reston virus (RESTV), Sudan virus (SUDV) and Taï Forest virus (TAFV); Fig. 1) or to the genus Marburgvirus (Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV))2. The WHO International Classification of Diseases Revision 11 (ICD-11) of 2018 recognizes two major subcategories of filovirus disease (FVD): Ebola disease caused by BDBV, EBOV, SUDV or TAFV, and Marburg disease caused by MARV or RAVV. Ebola virus disease (EVD) is defined as a disease only caused by EBOV. This subcategorization of FVD is largely based on the increasing evidence of molecular differences between ebolaviruses and marburgviruses, differences that may influence virus–host reservoir tropism, pathogenesis and disease phenotype in accidental primate hosts2.

Fig. 1. Filovirus taxonomy and Ebola virus transmission.

a | Taxonomy of the genus Ebolavirus. Thus far, five ebolaviruses have been associated with human infections, and four of them have been identified as pathogens. b | The natural reservoir host(s) of Ebola virus (EBOV) has (have) yet to be identified. Multiple data indicate a direct or indirect role of bats in EBOV ecology, but to date, EBOV has not been isolated from, nor has a near-complete EBOV genome been detected in any wild animal279. However, it is tempting to speculate that Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a zoonosis (that is, an infectious disease caused by an agent transmitted between animals and humans) because retrospective epidemiological investigations have often been able to track down the probable index cases of EVD outbreaks. These individuals had been in contact with wild animals or had handled the carcass of a possible accidental EBOV host7,280. c | Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image of EBOV particles (green) budding from grivet cells. d | Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) image of EBOV particles (green) budding from grivet cells1,281. aThe kingdom name has been approved by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) but has yet to be ratified. Parts c and d courtesy of J. Wada and J. Bernbaum, NIH/NIAID Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick, Frederick, MD, USA.

Since the discovery of filoviruses in 1967 (ref.3), 43 FVD outbreaks (excluding at least five laboratory-acquired infections) have been recorded in or exported from Africa4. The epidemiological definition of outbreak is one or more cases above the known endemic prevalence. For example, the single case of TAFV infection recorded in a setting in which FVD had never been reported before (Côte d’Ivoire)5 is still considered an outbreak. All FVD outbreaks, with the exception of that caused by TAFV, were characterized by extremely high case–fatality rates (CFRs, also known as lethality). Until 2013, the most extensive outbreak, caused by SUDV, involved 425 cases and 224 deaths (CFR 52.7%)6. The overall limited numbers of FVD cases (1967–2013: 2,886 cases including 1,982 deaths4), the typical remote and rural locations of outbreaks and the often delayed announcement of new outbreaks to the international community7 have prevented the systematic study of clinical FVD in humans. Thus, the commonly used description of FVD was derived either from observation of small groups of patients in care settings that were not well-equipped for diagnosis, treatment and disease characterization, or from observations of even smaller samples, such as individuals who were transferred from Equatorial Africa to Europe and the USA or who fell sick in Europe or the USA after contracting the virus elsewhere. Pathological characterization of FVD via autopsies has been rare7,8. In the absence of extensive human clinical data, FVD could only be defined further via the use of experimental animal infections9,10.

Until 2013, most EVD outbreaks originated from Middle Africa: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo. From late 2013 to early 2016, EBOV caused the largest outbreak to date, which spread from Guinea to other countries in Western Africa, leading to 28,652 human infections and 11,325 deaths11. The location and scale of the 2013–2016 outbreak was entirely unexpected12. Consequently, local, national and international organizations were caught unprepared for an outbreak caused by what, until then, was considered an exotic pathogen of largely negligible consequence for global public health13–15. After the WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, the global and local responses to the outbreak intensified. Ultimately, the outbreak was contained, but it devastated individuals, families, communities, health-care systems and economies16. In most affected countries, the response included the establishment of Ebola (virus disease) Treatment Units (ETUs)17–19, in which medical professionals and biomedical scientists managed large cohorts of patients with suspected or confirmed EVD in controlled settings. From this experience, scientists were able to better understand a virus previously best known as a potential bioweapons agent20,21. In addition to the Western African outbreak, an ongoing outbreak in the Ituri, Nord-Kivu and Sud-Kivu Provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is the second largest outbreak in terms of the number of cases and deaths, with 3,418 infections and 2240 deaths (as of 28 January 2020)22 (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Ebola virus disease outbreaks statistics

| Country (year) | Case–fatality rate (%) | Number of cases |

|---|---|---|

| COD (then Zaire) (1976) | 88.1 | 318 |

| COD (then Zaire) (1977) | 100.0 | 1 |

| Gabon (1994–1995) | 61.5 | 52 |

| COD (then Zaire) (1995) | 77.3 | 317 |

| Russiaa (1996) | 100.0 | 1 |

| Gabon (1996) | 67.7 | 31 |

| Gabon, also exported to South Africa (1996–1997) | 74.2 | 62 |

| Gabon, COG (2001–2002) | 78.2 | 124 |

| COG, also exported to Gabon (2002) | 90.9 | 11 |

| COG (2002–2003) | 89.5 | 143 |

| COG (2003–2004) | 82.9 | 35 |

| Russiaa (2004) | 100.0 | 1 |

| COG (2005) | 81.8 | 11 |

| COD (2007) | 70.5 | 264 |

| COD (2008–2009) | 46.9 | 32 |

| Guinea, also exported to Liberia, Mali, Senegal, Sierra Leone and USA; from Liberia, cases were exported to France, Germany, Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Spain and USA and, from Sierra Leone, to Italy, UK, Switzerland and USA (2013–2016) | 39.5 | 28,652 |

| COD (2014) | 71.0 | 69 |

| COD (2017) | 50.0 | 8 |

| COD (2018) | 61.1 | 54 |

| COD, also exported to Uganda (2018 to present) | 66.3 | 3,324 |

Country abbreviations are as used by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). COD, Democratic Republic of the Congo; COG, Republic of the Congo. aLaboratory-acquired infection. Modified and updated from ref.4.

Fig. 2. Ebola virus disease outbreaks.

The map shows the location and years of all reported Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreaks. Two cases of laboratory-acquired EVD occurred in Russia (not shown). Adapted with permission of McGraw-Hill Education, from Harrison’s principles of internal medicine, Jameson, J. L. et al, vol. 2, 20th edn, 2018 (ref.282).

Owing to observations from the 2013‒2016 Western African outbreak and, to a limited degree, from subsequent EVD outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Table 1)23–26, clinicians can now better describe predictable phases in the progression of EVD in humans. Typically, EVD begins with a nonspecific febrile illness followed by severe gastrointestinal symptoms and signs. In highly viraemic patients who often also have dysregulated immune responses, EVD progresses to a complex multiple organ dysfunction syndrome that can be fatal. A subset of patients, usually with lower viraemia, have less-severe disease progression and organ dysfunction27,28. Ultimately, these patients develop robust immune responses leading to clearance of viraemia and a resolution phase. However, recovery can be complicated by long-lasting clinical sequelae and/or virus persistence in immune-privileged sites that can lead to disease flares and even sexual transmission. In this Primer, we outline the current improved understanding of EVD based on the most recently published human clinical data.

Epidemiology

Classic epidemiology

Since the discovery of EBOV in 1976 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire)29–31, at least 17 EVD outbreaks have originated in Gabon, Guinea, the Republic of the Congo or Zaire/Democratic Republic of the Congo. At the time of writing, ~33,604 EBOV infections in humans, including 14,742 deaths (average CFR 43.8%) are on record4,22, although case numbers differ slightly from source to source.

Outbreaks and transmission

Most outbreaks can be traced back to a single spillover introduction of EBOV into the human population from an unknown reservoir by unknown means. Subsequently, the virus is transmitted by direct, typically non-aerosol, human-to-human contact or contact with infected tissues, bodily fluids or contaminated fomites (Fig. 1)4. Based on historical records, EBOV may have been transmitted from its natural reservoir host(s) to humans to cause disease only about 20–30 times (Table 1), although it is probable that limited EVD outbreaks may have been overlooked or not reported. The potential for infection of an index case and subsequent spread — locally and globally — has been estimated by considering reservoir species distribution, along with governance, communications, isolation, infrastructure, health care and international connectivity32. These predictions are crucial to identify regions that require increased surveillance and investments. Tracking EBOV within the human population after a zoonotic transmission event can be challenging, especially as the single natural reservoir has not been identified.

A strong risk factor linked to human-to-human EBOV propagation is contact with infected bodily fluids33–35. Indeed, infectious EBOV has been recovered from breast milk, saliva, urine, semen, cerebrospinal fluid, and aqueous humor, in addition to blood and blood derivatives, and detected in amniotic fluid, tears, skin swabs and stool by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR36–40. Although EBOV RNA has been detected in illness-related bodily fluids (such as diarrhoea and vomitus)40, infectivity is unclear. Taking care of an individual with EVD at home or in a health-care facility or following traditional funeral practices, which involve contact with the deceased’s body, substantially increases the risk of acquiring infection. This contact is one of the reasons why women, who traditionally care for the sick in certain African regions, may be at higher risk of acquiring EBOV than men41,42 (Box 1). Although rare, sexual transmission of EBOV was proven or strongly suspected during the Western African EVD outbreak. Fortunately, the risk of widespread outbreaks in middle-income and high-income countries remains relatively low, partially owing to our ability to keep the reproductive number (R0, the average number of individuals to whom an infected person will transmit the pathological agent over the course of the infectious period) of EBOV below 1 with simple infection prevention control and contact tracing measures43.

Box 1 Anthropology in filovirus disease outbreak control.

The initial spillover and spread of filoviruses, the eventual perpetuation of filovirus disease (FVD) and the general knowledge of these viruses and their associated diseases among health-care and research professionals and the general population are heavily influenced by the social dynamics and the anthropological environment of outbreak areas. Understanding of and respect towards individuals in these settings and the drivers of human behaviour are crucial to the building of trust and to increase the effectiveness of communication among locals and those who could be considered ‘outsiders’ or ‘other’. In the absence of such trust and communication, even the most advanced outbreak intervention strategies are doomed to failure. Professional anthropologists were first integrated into FVD outbreak response teams at the beginning of the millennium during outbreaks in Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, South Sudan and Uganda266–268, and have since become important, although probably still under-represented, actors in FVD emergency public health response teams. Anthropological and sociological approaches have helped to describe, explain and curtail rumours about the origin of, for instance, Ebola virus disease (EVD) while working within local belief systems rather than dismissing them. These approaches have managed to increase the safety of traditional funerals and day-to-day human interactions via the integration of highly esteemed traditional healers, local chiefs and other revered personalities in response teams, and they have informed the creation and distribution of community-accepted educational material (such as posters, booklets and songs) in local languages via community centres, radio and TV broadcasting stations, or mobile phones269–274. Since FVD outbreak areas are linguistically, ethnically, religiously and developmentally highly diverse, no one-size-fits-all approach to FVD containment can currently be envisaged, and specialized anthropologists will remain paramount in supporting outbreak response teams in the mission to mitigate or end human disease burden.

Risk factors and outcomes

Demographical risk factors for EBOV infection and subsequent development of EVD, such as age, sex and ethnicity, are not well-defined. By current (albeit incomplete) understanding, sex differences in susceptibility have not been identified, but women as care-givers may be at higher risk of being exposed to EBOV, and the incidence of EVD increases almost linearly with age to a peak at 35–44 years. Although children typically constitute a disproportionately small number of EVD cases, they have shorter incubation periods, and a more rapid disease course. Children have a higher risk of death than older populations, with children of <5 years of age at the highest risk44–49. Possible explanations for the low incidence of EVD in children include behavioural factors, such as deliberate prevention of exposure to infected individuals46, and differences in susceptibility across age groups50. Occasionally, spikes in incidence of EVD in children have been recorded in correspondence to malaria outbreaks and were probably related to nosocomial infections28.

Infected pregnant women are at high risk of miscarriage or stillbirths, and newborn babies of infected mothers rarely survive51. Indeed, EBOV can be transmitted transplacentally52 and also lead to fetal death related to placental insufficiency. Transmission of EBOV from infected pregnant women to their embryos or fetuses or from infected mothers to their children occurs frequently and is associated with elevated in utero and neonatal lethality51. The risk of fetal loss in survivors of EVD who become pregnant after recovery remains unclear; some data suggest an increased risk over baseline, especially early after recovery53, although healthy pregnancy outcomes are possible54. EBOV RNA has been detected at high concentrations in amniotic fluid, placenta, fetal tissue and breast milk39,55–58. Molecular studies of specific host factors influencing the outcome of EBOV infection in particular human populations are absent, with the exception of one study that associated the expression of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) 2DS1 (KIR2DS1) and KIR2DS3 with fatal outcome59.

Case–fatality rate

Although unpublished observations of varying disease clinical signs or levels of severity depending on the specific outbreak have been described, these findings are not necessarily reflected in the published literature. On the basis of comparative statistics on CFRs, a fundamental difference in virulence between ebolaviruses that cause lethal human disease is not observed; the oft-repeated notion that EBOV is the most virulent ebolavirus (let alone filovirus) is not supported by available data4. The mean CFRs for each ebolavirus are 33.65 ± 8.38% (BDBV), 43.92 ± 0.7% (EBOV) and 53.72 ± 4.456% (SUDV)4; that is, a CFR of ~40–50% overall, with the remaining difference between the viruses compounded by the number of outbreaks recorded and the typically small number of cases in each outbreak. Accordingly, whether one ebolavirus is more dangerous than another is statistically unclear. The reasons for fluctuating CFR data are not truly understood. Possible reasons include differences in health status (nutrition, immunity and co-infection status), genetics (ethnicity-dependent haplotypes or random polymorphisms), health-seeking behaviour, case recognition and reporting capacities and the development and accessibility of health-care facilities providing supportive care in the affected African countries.

Case definitions

In response to large outbreaks of communicable diseases such as meningitis and yellow fever, in 1998, the WHO African Regional Office (WHO/AFRO) along with its Member States established an Integrated Disease Surveillance strategy (later termed Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR)) to improve public health surveillance of and response to emerging and re-emerging diseases, including those with outbreak potential60. Revised IDSR guidelines from 2010 include guidance for developing case definitions for routine and community-based surveillance of such diseases. For EVD, the WHO has developed standard case definitions for alert, suspected, probable and confirmed cases in the context of routine and community-based surveillance (Box 2; US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definitions are in Box 3). These standard case definitions are utilized by public health authorities to optimize surveillance and notification of EVD, particularly before an outbreak has been identified.

As increasing numbers of patients with possible EVD present to health facilities at the beginning of an outbreak, case definitions are refined from standard public health case definitions to reflect clinical and epidemiological features associated with a particular outbreak context. A robust case definition and accurate confirmatory testing are key to ensuring that individuals with suspected EBOV infection are efficiently identified and, upon admission to an ETU, isolated for confirmation of diagnosis and treatment. Importantly, patient screening time should be minimized to limit exposure of uninfected individuals, including ETU staff, to potentially infected individuals. Within an ETU, patients with suspected EBOV infection may be further separated, based on the probability of EBOV infection or the risk of infectiousness, to avoid nosocomial infection within the ETU. The corresponding jargon for ETU wards or sections of wards to reflect levels of risk (of having EVD, and therefore infectiousness) has varied across ETUs and has included descriptions such as ‘suspect vs probable’ or ‘wet vs dry’.

Despite refinement, case definitions are rarely 100% sensitive or specific, and attempts to optimize one come at the expense of the other. A case definition with a low sensitivity will mislabel true EBOV-positive individuals as EBOV-negative, leading to an increased risk of discharge of EBOV-infected individuals back to the community, where EBOV transmission can be reinitiated. Particularly in a setting with a low community incidence of EVD, the sensitivity of the case definition should be maximized. By contrast, a case definition with a low specificity might result in misclassification of true EBOV-negative individuals as EBOV-positive. Such individuals might be admitted to an ETU with suspected EVD, placing them at increased risk of EBOV exposure and nosocomial infection, especially when the probability that other patients with suspected EVD might be EBOV-positive is high. Thus, in a community with a high incidence of EVD, increased specificity in EVD case definition may be crucial.

Given these considerations, currently no EVD case definition is globally applied. Indeed, the EVD case definition can be reiterated during the course of an outbreak; such variations in case definition were used during the 2013–2016 Western African outbreak (for example, in Sierra Leone61) as the outbreak evolved from a high incidence to a low incidence. Although novel case definitions are limited by variations in EVD prevalence during a particular outbreak and the intrinsic lack of specificity of case definitions compared with common endemic causes of acute febrile and diarrhoeal disease, their performance characteristics have been evaluated (Box 4).

Box 2 WHO case definitions.

Standard case definitions for alert cases (community-based surveillance)

Illness with onset of fever and no response to treatment of usual causes of fever in the area; OR

At least one of the following signs: bleeding, bloody diarrhoea, bleeding into urine; OR

Any sudden death

Standard case definitions for suspected and confirmed cases (routine surveillance)

Suspected case: Illness with onset of fever and no response to treatment for usual causes of fever in the area, and at least one of the following signs: bloody diarrhoea, bleeding from the gums, bleeding into the skin (purpura), and bleeding into the eyes and urine

Confirmed case: A suspected case with laboratory confirmation (positive IgM antibody, positive PCR or viral isolation)

Case definition for a suspected case during an Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak (to be used by mobile teams, health stations and health centres)

Any person, alive or dead, suffering or having suffered from a sudden onset of high fever and having had contact with an individual with suspected, probable or confirmed EVD or a dead or sick animal; OR

Any person with sudden onset of high fever and at least three of the following symptoms: headache, lethargy, anorexia or loss of appetite, aching muscles or joints, stomach pain, difficulty swallowing, vomiting, difficulty breathing, diarrhoea, hiccups; OR

Any person with inexplicable bleeding; OR

Any sudden, inexplicable death275

Case definition for a probable case (for exclusive use by hospitals and surveillance teams)

Any patient with suspected EVD evaluated by a clinician; OR

Any deceased patient with suspected EVD (in whom it has not been possible to collect specimens for laboratory confirmation) that has an epidemiological link with a patient with confirmed EVD

Case definition for a laboratory-confirmed case (for exclusive use by hospitals and surveillance teams)

Any patient with suspected or probable EVD with a positive laboratory result. For laboratory confirmation, the patient must test positive for the virus antigen, either by detection of virus RNA by PCR with reverse transcription or by detection of IgM antibodies directed against EBOV.

Box 3 CDC definition for a person under investigation for EVD.

Individual with both “1. Elevated body temperature or subjective fever or symptoms, including severe headache, fatigue, muscle pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, or unexplained hemorrhage; AND 2. An epidemiologic risk factor within the 21 days before the onset of symptoms”276.

Such risk factors include direct contact with “blood or bodily fluids (urine, saliva, sweat, feces, vomit, breast milk, and semen) of a person who is sick with or has died from […] (EVD)”, “objects (such as clothes, bedding, needles and medical equipment) contaminated with bodily fluids from a person who is sick with or has died from EVD”, “infected fruit bats or nonhuman primates (such as apes and monkeys)”, and “semen from a man who recovered from EVD (through oral, vaginal, or anal sex)”277.

Box 4 Case definition during an outbreak.

A retrospective cohort study from a holding unit (a temporary holding facility for patients with suspected or confirmed EVD waiting for a bed in an ETU) in Freetown, Sierra Leone, reported the clinical characteristics of 724 individuals who underwent EBOV PCR testing from May to December 2014 (ref.146). The standard case definition adapted by the Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Sierra Leone from the existing WHO case definition had suboptimal performance, with a sensitivity of 57.8% and a specificity of 70.8%. A subgroup analysis revealed that 15 (9%) of 161 patients with confirmed EVD lacked two of the major criteria required to fulfil the EVD case definition; that is, history of fever and risk factor for EVD exposure. Separately, an Ebola (virus disease) Prediction Score was developed to improve the performance characteristics of the existing case definition278. This score was derived from a retrospective analysis of clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 382 individuals presenting to a Liberian ETU from September 2014 to January 2015 and included the following six predictors of EVD: contact with an individual with EVD, diarrhoea, anorexia, myalgia, dysphagia and absence of abdominal pain. With an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.75 (95% CI 0.70–0.80) for the prediction of laboratory-confirmed EVD, the prediction score performed at a moderate level for determining EVD status in patients with suspected EVD. Although it was not practically useful for determining EVD status in place of EBOV-specific laboratory testing, the Ebola Prediction Score has promising utility for aiding clinicians to improve risk stratification and triage of patients with suspected EVD in future outbreak settings278.

Molecular epidemiology

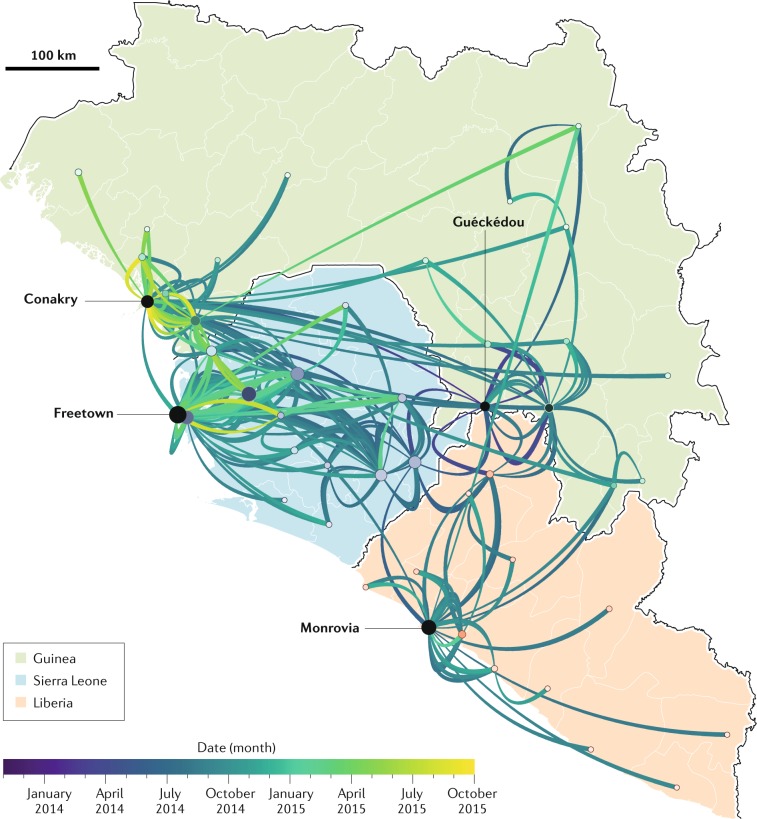

The 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak was the first to be largely characterized by molecular epidemiological evidence. Deep-sequencing efforts, often performed on site and in parallel by several groups, resulted in the determination of >1,600 coding-complete (all open reading frames) or near-complete (typically coding-complete plus parts of leaders and/or trailers) EBOV genomes directly from human patient samples62–65. These samples included single genomes from single patients, multiple different genomes from the same patient and the same genome from different patients. Subsequent phylogenetic analyses traced EBOV movement through the human populations of all affected countries and pinpointed multiple back-and-forth border crossings63 (Fig. 3). The genomic data confirmed the classic epidemiological model of filovirus infections: all 28,652 human infections of this outbreak occurred via direct human-to-human contact tracing back to a single human index case (probably due to zoonotic transmission) close to Guéckédou, Nzérékoré Region, Guinea. Such molecular epidemiological investigations are now becoming routine.

Fig. 3. Reconstructed EBOV transmission chains during the 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak.

Molecular evidence using hundreds of individual Ebola virus (EBOV) genomes sequenced from individual patients indicates that in the index case of the outbreak, EBOV was acquired by unknown means at the end of 2013 in or around Guéckédou in Guinea. From there, person-to-person transmission enabled EBOV to spread (coloured lines) throughout the country, to cross borders and ultimately to affect a total of 15 countries (see also Fig. 2). The direction of EBOV spread is represented by the lines and goes from the thick end to the thin end. White borders delineate the provinces (Guinea), districts (Sierra Leone) and counties (Liberia). Adapted from ref.63, Springer Nature Limited.

Molecular approaches have also enabled progress in understanding of within-outbreak and within-host viral evolution69. During the two most recent EVD outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, deep sequencing revealed single spillover EBOV transmission events into the human populations with subsequent person-to-person transmission25,26. Molecular approaches revealed that sexual transmission of EBOV may rarely occur from apparently healthy survivors of EVD in whom EBOV may persist in the semen for extended periods of time, with the latest documented transmission event 482 days after EVD onset41,66–68. The importance of molecular epidemiology is not limited to an individual outbreak but provides valuable information to scientists and decision makers regarding the long-term evolution of EBOV. Current medical countermeasures (MCMs), such as vaccines and therapeutics, have often been designed to specifically match a known EBOV isolate, or designed as a consensus of multiple ones to account for genomic variation. Molecular epidemiology enables assessment of the potential efficacy of available MCMs based on the sequence of a newly circulating EBOV isolate. The analysis of 65 EBOV GP sequences from isolates collected from 1976 to 2014 demonstrated that the temporal evolution of EBOV is mostly due to neutral genetic drift, suggesting that the emergence of completely novel isolates that would not respond to current MCMs is unlikely70.

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

Many outstanding questions still surround the pathophysiology of EVD. Findings from animal studies, in vitro work and clinical data from humans are beginning to decipher the normal course of EVD in humans and to link disease progression to the molecular bases of EBOV pathogenesis. With these data, researchers may be able to identify the crucial pathways involved in effective immune responses to EBOV infection and the various candidate MCMs that may be developed to augment any host response shortcomings.

Animal models

Exposure of immunocompetent laboratory mice, Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) and domesticated guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) to EBOV does not yield severe (or any) disease, and EBOV must be adapted via serial passages in rodents before lethal infection is achieved71,72. Even when adapted viruses are used, these rodent models do not fully mimic human disease. Because non-human primates (NHPs) are evolutionarily much more closely related to humans than rodents, NHP models of EVD are often considered to be more useful for the study of human EBOV infection and EVD. Indeed, much of the information on viral pathogenesis has been derived from studies with wild-type EBOV predominantly in crab-eating macaques (Macaca fascicularis) and rhesus monkeys (M. mulatta)9,10. On the basis of experimental animal data, two factors that may influence development and severity of human EVD may be the EBOV exposure route and dose. Direct contact with infected biological materials or contaminated non-biological materials via cuts or scratches or via contact with mucosal membranes (oral or, theoretically, nasopharyngeal or conjunctival mucosa) is considered the most frequent mode of human-to-human EBOV transmission73. However, these transmission pathways are difficult to simulate in experimental settings. Thus, animal models of EVD have been established using injection and aerosol methods of EBOV exposure to model accidental needlestick injury and respiratory routes of exposure, respectively, despite the lack of evidence that these exposure routes have any relevant roles during natural EVD outbreaks73.

Most studies in NHPs rely on either intramuscular injection or small-particle aerosol exposure of 1,000 plaque-forming units (pfu) of EBOV, a dose that ensures that all infected animals will develop a disease that is almost always lethal74; thus, significant results can be achieved with overall low animal numbers. Interestingly, intramuscular infection of NHPs with some EBOV variants by injection of a calculated dose of 0.01 pfu (corresponding to ~90 virus particles) results in lethal disease in 100% of animals75. The lethality associated with this low virus dose suggests that very few virions may be required to initiate a lethal disease course in humans, although insufficient data preclude robust median lethal dose calculation and speculations on the effects of different variants on human disease.

During the 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak, molecular genomic analyses were used to observe EBOV evolution during human-to-human transmission. The comparison of the ~1,600 near-complete EBOV genome sequences obtained during that outbreak revealed several positively selected genomic mutations. A mutation leading to an amino acid residue change, A82V, in EBOV glycoprotein GP1,2 occurred in viral genomes isolated from samples collected early in the 2013–2016 Western African outbreak and remained present in genomes from all later samples76–78. In vitro, this mutation enhances EBOV GP1,2-mediated virus entry into human cells78, possibly by weakening the stability of the prefusion conformation of GP1,2 and hence lowering the activation barrier required for fusion of EBOV particle membranes with host cell membranes79. However, in vivo experiments have yet to unambiguously ascribe a phenotype to A82V and similar mutations in the context of pathogenesis. For instance, initial studies with Ifnar−/− immunodeficient laboratory mice and rhesus monkeys did not demonstrate an effect of A82V on disease severity or virus shedding80. This lack of an effect may be due to the true lack of effect of these mutations on pathogenesis, limitations of the in vivo studies (such as compensatory mutations for the A82V phenotype observed in vitro), or intrinsic differences among laboratory mice, NHPs and humans, such as infection cofactors or immune responses. Consequently, a convincing explanation for positive selection of certain mutations in EBOV genomes over the course of the outbreak is still lacking. Novel approaches using systems biology are used more frequently nowadays in the context of EVD and could be used to further describe the effect of such mutations on pathogenesis and transmission of EBOV81,82.

Host–pathogen determinants of outcome

Elucidation of the mechanistic determinants of the outcome of host–filovirus interaction has historically been challenging. In humans, outcome could only be correlated with very limited clinical data, providing only low-resolution associations. In proxy animal disease models, the homogeneity of highly stringent uniformly lethal models prevents the identification of any host-specific or filovirus-specific variability, much less mechanistic determinants. Ongoing analyses of samples acquired during the 2013–2016 Western African outbreak are using a systems approach to understanding the consequences to the host81,82, although these studies are at an early stage. Finally, although in vitro systems have provided valuable information regarding molecular pathogenesis, a complex variety of viruses, host cells and experimental conditions have been used. Accordingly, a single, unified picture of the host–filovirus interaction does not exist. Instead, from a ‘patchwork’ compilation of different and complex observations, key aspects of the disease in humans remain unknown.

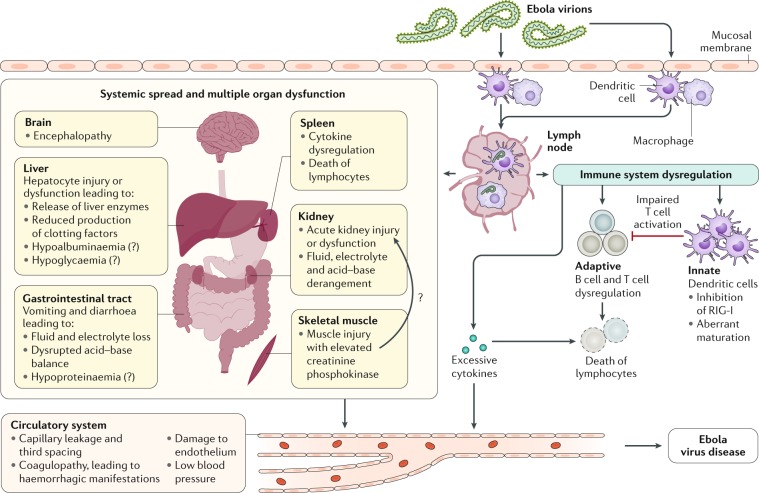

EBOV tissue and cell tropism are primarily determined by the EBOV glycoprotein GP1,2, GP1,2 attachment factors on the host cell surface and the intracellular binding of GP1,2 to the NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 (NPC1, also known as Niemann–Pick C1 protein) receptor83,84 (Fig. 4). Most human cells can become infected, but mononuclear phagocytes (for example, Kupffer cells in the liver, macrophages and microglia) and dendritic cells are primary EBOV targets74,85–91. As the primary target cells become infected, they probably facilitate further virus dissemination86 and migrate to the regional lymph nodes and to the liver and spleen88. In vitro, infected macrophages are activated by binding to EBOV GP1,2 (ref.92) to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, in particular interleukins IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8, and tumour necrosis factor (TNF). These secretions probably result in the recruitment of additional EBOV-susceptible macrophages to the site of infection and, ultimately, the breakdown of endothelial barriers. In NHP models, this breakdown frequently causes third spacing (that is, excess movement of intravascular fluid into interstitial spaces), leading to oedema and hypovolaemic shock. Although described, this manifestation is less well characterized in human patients91,93–95. In vitro, dendritic cells react to EBOV infection with partial suppression of major histocompatibility complex class II responses, expression of tissue factor and TNF ligand superfamily member 10 (TNFSF10), increased production of chemokines (for instance, C-C motif chemokine 2 (CCL2), CCL3, CCL4 and IL-8) and suppressed secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines96–100. Together with possible abortive infection101, the aberrant cytokine responses and TNFSF10 expression are probably key to the extensive lymphocyte death. Such lymphocyte depletion possibly contributes to the susceptibility of patients with EVD to acquiring secondary infections)88,102, hypotension, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and ultimately multiple organ dysfunction syndrome that is typical of EVD8,102–104 (Fig. 5).

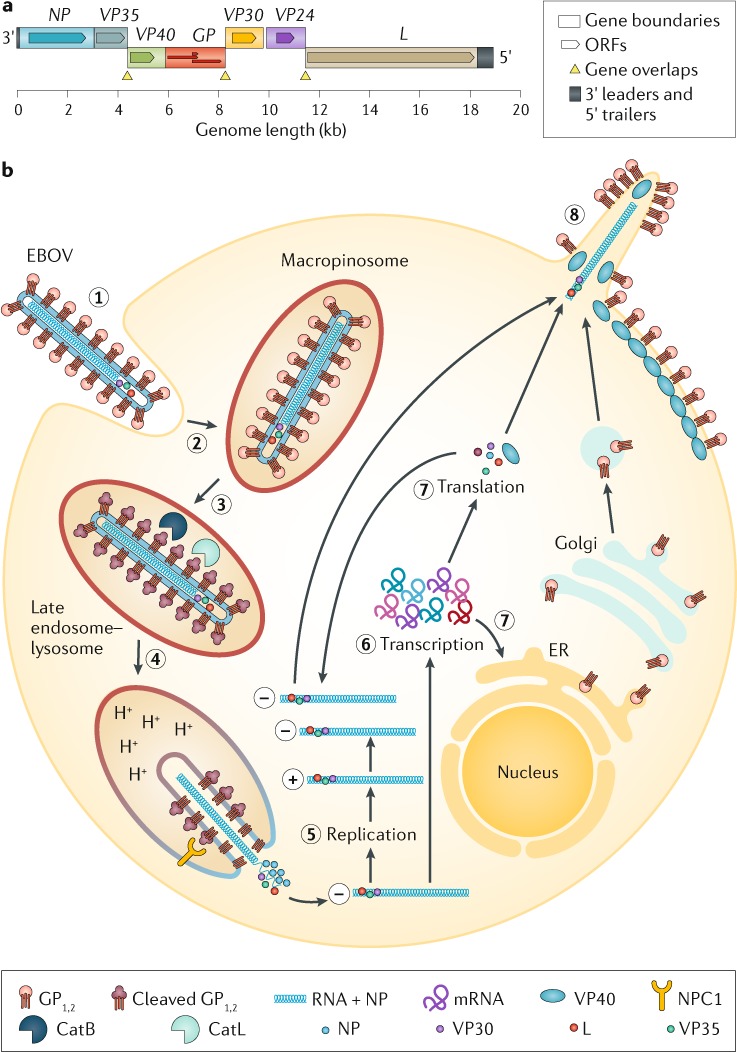

Fig. 4. EBOV genome and life cycle.

a | Ebola virus (EBOV) has a linear, non-segmented, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA genome (~19 kb) expressing seven structural proteins and several non-structural proteins from seven genes: NP encodes nucleoprotein NP, VP35 polymerase cofactor VP35, VP40 matrix protein VP40, GP glycoprotein GP1,2 and secreted glycoproteins (not shown), VP30 transcriptional activator VP30, VP24 RNA complex-associated protein VP24, and L large protein L1,281. b | The binding of EBOV particles to the attachment factors on the host cell surface is mediated by the homotrimeric structural glycoprotein GP1,2, which is formed of three heterodimers consisting of subunits GP1 and GP2 that are connected by a disulfide bond (1). Binding to the host cell membrane triggers viral particle endocytosis (2). In the late endosome, GP1,2 is sequentially cleaved by cathepsin B (CatB) and cathepsin L (CatL) (3) to expose the receptor-binding site of the GP1 subunit. A low pH induces GP1 interaction with the EBOV receptor NPC1, with subsequent GP2-mediated fusion of the particle envelope with the endosomal membrane and thereby expulsion of the ribonucleoprotein complex (predominantly RNA + NP) into the cytosol (4). There, the filovirus genome is replicated (5) and the filovirus genes are transcribed into mRNAs (6). Viral proteins are translated in the cytosol or, in the case of GP1,2, into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (7). Mature progeny ribonucleoprotein complexes and viral proteins are transported to the plasma membrane, where particle budding occurs (8). NPC1, NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 1; ORF, open reading frame. Part a courtesy of J. Wada, NIH/NIAID Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick, Frederick, MD, USA. Part b adapted from ref.283, Springer Nature Limited.

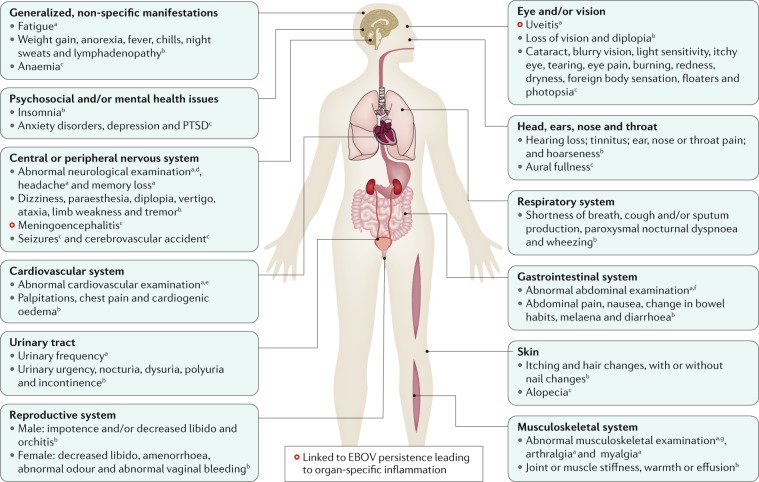

Fig. 5. Conceptualized EVD pathogenesis.

Ebola virus particles enter the body through dermal injuries (microscopic or macroscopic wounds) or via direct contact via mucosal membranes. Primary targets of infection are macrophages and dendritic cells. Infected macrophages and dendritic cells migrate to regional lymph nodes while producing progeny virions. Through suppression of intrinsic, innate and adaptive immune responses, systemic distribution of progeny virions and infection of secondary target cells occur in almost all organs. Key organ-specific interactions occur in the gastrointestinal tract, liver and spleen, with corresponding markers of organ injury or dysfunction that correlate with human disease outcome. The question marks indicate speculated manifestations. RIG-I, antiviral innate immune response receptor RIG-I.

Immune responses

Although considerable progress has been made towards understanding the immune response to EBOV infection at the cellular level using in vitro testing, data are limited regarding the systemic immune response in humans following infection. Prior to the 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak, which was of such a scale and duration to enable study, opportunities were lacking to conduct thorough and simultaneous immunological analyses of the human host response to EBOV infection.

EBOV inhibits induction of intrinsic (cell-based antiviral defence mechanisms via proteins that are constitutively expressed and target specific viruses) and innate (cell-based antiviral defence mechanisms via proteins that are induced by infection and rely on pattern recognition receptors) host immune responses105,106. This inhibition permits efficient virus replication in host cells, thereby accelerating viral spread. To this end, the virus invests a substantial amount of its genome coding capacity. Perhaps the best studied inhibitor is the EBOV polymerase cofactor VP35, which is also a type I interferon (IFN) antagonist. EBOV VP35 suppresses production of type I IFN (by impairing IRF-3 phosphorylation) through its ability to bind double-stranded RNA and through direct interactions with the host proteins TBK-1, IKKε and PACT (refs107–115). In addition, VP35 suppresses micro-RNA silencing (an important post-translational regulatory pathway) in the host cell116, and GP1,2 antagonizes a cellular antiviral restriction factor, BST-2 (ref.117). A second EBOV-encoded protein, RNA complex-associated protein VP24, also inhibits the antiviral response by preventing the nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 1α/β (STAT1), which is induced by type I IFN and acts as a transcription factor to increase expression of antiviral proteins118,119. Finally, EBOV VP40 is incorporated into exosomes that seem to have the potential to disrupt or kill host immune cells120,121.

Recent studies have confirmed that although EBOV has been considered immunosuppressive, EBOV-specific cellular and humoral immune responses develop but are often outpaced in the host–pathogen EVD ‘arms race’122,123, in which timing seems crucial. This host–pathogen competition might also be applied to vaccine-mediated mechanisms of protection. A vaccinated individual is assumed to be protected once outside the window for a vaccine-induced mounting of a humoral response (for example, ~10 days for the vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus-based vaccine rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP as defined by the Ebola ça Suffit! ring vaccination trial)124,125. Ongoing vaccine and clinical research efforts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo will help to clarify the relationship between timing of vaccine receipt with susceptibility to infection. In addition, in vaccinated individuals who then become infected, further research will clarify the relationship between previous vaccination and subsequent EVD severity or outcome. Indeed, in vaccinated individuals who then develop EVD, receipt of the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine is independently associated with a decreased risk of dying126. Research on human immune responses to EBOV infection has focused largely on the detection of biomarkers of inflammation (such as CCL2, IL-8 and IL-6), endothelial dysfunction (such as selectin P), coagulation (such as d-dimer, tissue factor and von Willebrand factor) and lymphocyte function (such as CXCL3 and granzyme B)127,128; the expression of host RNA transcripts from peripheral blood mononuclear cells; and the appearance of EBOV-specific humoral and cellular immune responses.

Data from both patients with EVD treated in the USA and Western African cohorts suggest that robust adaptive immune activation, which includes antigen-specific T cell and B cell responses, occurs during acute illness123. Efforts are ongoing to define the characteristics of effective and ineffective B cell and T cell responses during acute infection and over time129,130. These limited results suggest a ‘race’ between EBOV proliferation and the ability of the human host to mount an effective and regulated anti-EBOV immune response. No study in humans has been able to measure inoculation dose and its relationship with disease severity. Interrogation of immune responses in four patients with EVD treated in the USA also revealed a second peak and persistence of T cell activation during convalescence123, which might implicate persistence of EBOV or EBOV antigen in tissue compartments (immune-privileged sites) after viral nucleic acid is no longer detected in the blood. Indeed, EBOV RNA has frequently been detected in semen from male survivors of EVD and from cerebrospinal and intraocular fluids from two convalescent patients long after blood samples tested negative for EBOV131–134.

Diagnosis, screening and prevention

Clinical manifestations of acute EVD

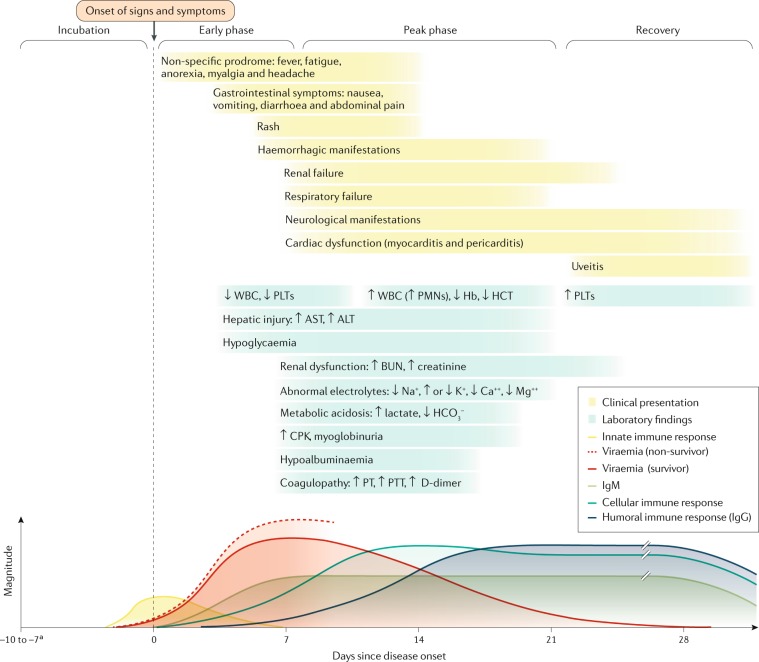

Given the difficulties in identifying the exposure source and route of infection in most patients, data that confidently determine the time from exposure to symptom onset are sparse. The most convincing data come from situations characterized by a single definitive exposure event. An analysis of all published human exposure data determined that the mean incubation period of EVD is 6.22 ± 1.57 days for all routes of exposure, 5.85 ± 1.42 days for percutaneous exposure and 7.34 ± 1.35 days for person-to-person contact or contact with infected animals135. Rarely, asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic infection of individuals without known clinical manifestations of EVD has been described136,137. A study of household contacts of survivors discharged from an ETU in Sierra Leone revealed that although 47.6% of contacts (229 of 481 contacts) had high-level exposures (direct contact with a corpse, bodily fluids or a patient with bleeding, diarrhoea or vomiting), an assay detecting anti-EBOV GP IgG from oral fluid samples tested positive only in 12.0% of contacts who reported having symptoms at the same time as household members who had EVD (11 of 92 contacts) and in 2.6% of contacts who reported having no symptoms (10 of 388 contacts)138. In general, patients with EVD have a predictable clinical course (Fig. 6). During early infection (days 1–3 following disease onset), patients present with a non-specific febrile illness (symptoms may include anorexia, arthralgia, headache, malaise, myalgia and rash) that progresses in the first week to severe gastrointestinal symptoms and signs (nausea, vomiting and high-volume diarrhoea). During the 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak, fatigue, anorexia, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting, fever and myalgia were among the most common clinical manifestations139–144.

Fig. 6. Conceptualized clinical course of acute EVD over time.

The time course of the clinical manifestations (top), laboratory findings (middle) and viraemia and immune responses (bottom) in patients with Ebola virus disease (EVD). The coloured lines in the top and middle panels do not have defined start and end points as these may vary. Renal dysfunction is common and not well-characterized in patients with EVD; it is probably a multifactorial combination of hypovolaemia (related to gastrointestinal fluid losses, decreased fluid input, fever, hypoalbuminaemia and sepsis pathophysiology), intrinsic renal injury (acute tubular necrosis related to myoglobin pigment injury secondary to rhabdomyolysis or direct viral infection of tubular epithelial cells) or cytokine-mediated nephrotoxicity. Whereas respiratory symptoms and signs may reflect respiratory compensation for a primary metabolic acidosis, primary causes of hypoxaemic respiratory failure include acute lung injury (related to systemic inflammatory response syndrome and/or sepsis or Ebola virus (EBOV)-related cytokinaemia), pulmonary oedema (in the setting of capillary leak or direct infection) and viral pneumonia. Respiratory muscle fatigue may also contribute to ventilatory respiratory failure. Haemorrhagic manifestations include oozing from venepuncture sites, haemoptysis (coughing up blood), haematemesis (vomiting blood), melaena (dark stools as a result of bleeding) and vaginal bleeding. Neurological manifestations include meningoencephalitis and cerebrovascular accidents (such as strokes). ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; Hb, haemoglobin; HCT, haematocrit; PLT, platelet; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocyte; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; WBC, white blood cell count. aIncubation periods of 2–21 days have been reported. Bottom panel adapted with permission from ref.284, The American Association of Immunologists, Inc.

As the EBOV load increases, typically the severity of EVD clinical manifestations increases as well. The onset of detectable viraemia and manifestations of clinical signs and symptoms in most patients occurs 6–10 days after exposure. Later in the first week of illness following disease onset, patients may have persistent fever and increased gastrointestinal fluid losses and hypotension from dehydration and, to a minor extent, vascular leakage. Rhabdomyolysis (the breakdown of muscle leading to the release of the contents of dead myofibres into the circulation) has also been observed145. Although EVD is still often referred to as a ‘viral haemorrhagic fever’, this term is discouraged2 because not all patients have overt bleeding manifestations and fever is not always present146,147. However, with observations of early consumptive coagulopathy followed by hypercoagulability in the recovery period, haematological abnormalities may be more common and complex than previously understood127,148. During the terminal phase (days 7–12 following disease onset), tissue hypoperfusion and vascular leakage, often in conjunction with dysregulated inflammation, lead to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and/or damage, including acute kidney injury. Kidney injury is evidenced by oliguria or anuria and abnormalities in electrolytes including potassium and sodium. A subset of patients develop central nervous system manifestations and encephalopathy. Although several underlying causes could be involved, EBOV RNA has been detected in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with EVD, suggesting that meningoencephalitis may be directly mediated by the virus149,150.

The clinical timeline and manifestations may be altered in children; although the incidence of EVD among children was lower than in adults across the three affected countries during the 2013‒2016 Western African EVD outbreak48, data regarding paediatric EVD suggest that the incubation period is shorter and the CFR is higher in younger children (<5 years of age) than in older children. Additionally, children were more likely than adults to clinically present with fever and less likely to report abdominal pain, arthritis, myalgia, dyspnoea (difficult breathing) and hiccups in the early stage of disease.

In humans, no EVD outbreak including more than a single case has ever resulted in a 100% CFR4. However, the clinical correlates of outcome following EBOV infection have been difficult to discern owing to challenges in data collection, clinical follow-up and limited laboratory services. Data from the 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak show that viral load or the RT quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) cycle threshold value (which is a proxy for the viral load), age, and signs of organ dysfunction, in this order, most reliably predict outcome. The cycle threshold value refers to the number of cycles of PCR amplification required before viral RNA is detectable above a background threshold. The cycle threshold cannot be universally related to a corresponding number of viral genome copies per millilitre of blood, as it depends on the specific experimental conditions. However, a low value means that viral DNA can be detected in a short period of time, which suggests a high viral load, whereas a high value is associated with a low viral load. For instance, data from an ETU in Sierra Leone suggested a poor prognosis in patients admitted with viral loads >10 million genome copies per millilitre of blood151. The mean initial viral load at this ETU decreased over the course of the outbreak, as did the CFR, although such decreases occurred in the setting of numerous potential explanatory factors27. Other risk factors that have been sporadically linked with a fatal outcome include age ≥45 years, fever >38 °C, weakness, dizziness, diarrhoea, conjunctivitis, difficulty breathing or swallowing, confusion or disorientation, coma, haemorrhagic signs and laboratory evidence of hepatocellular damage (for example, increased concentration of blood aspartate aminotransferase AST)) and impaired kidney function (for example, increased concentrations of blood urea nitrogen and creatinine)45,152–154. These risk factors are an aggregate list from several distinct cohorts during the same outbreak; however, different associations were found in different cohorts, partially because the same factors were not measured across all cohorts. An increase in overall lethality has also been observed in patients co-infected with Plasmodium falciparum (the causative agent of falciparum malaria) and potentially plasmodia of other species155,156.

Diagnosis of acute EVD

In tropical areas, where numerous febrile illnesses can mimic the presentation of EVD, testing for or empirically treating parasitic (for example, Plasmodium spp.), viral (for example, Lassa virus) and bacterial (for example, Salmonella Typhi) diseases is an important consideration156,157. Given the frequency of co-infection with Plasmodium spp., the aetiological agents of malaria, all patients should receive malaria rapid diagnostic testing or be treated empirically for uncomplicated or severe malaria.

Appropriate isolation of patients with laboratory-confirmed EVD not only requires optimization of a front-line clinician’s ability to rapidly identify a patient with disease that fits the EVD case definition (see Epidemiology) but also necessitates that an EVD diagnosis is accurately confirmed with readily available laboratory tests. Until recently, field diagnosis of EVD during an outbreak has relied primarily on real-time RT-PCR assays. Although PCR assays are accurate, factors such as cost, time to processing (including sample transport time), availability and required level of operator expertise contributed to delays in provision of rapid results during the 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak. Improving the time to diagnosis, which includes measures to identify patients prior to the onset of symptoms, may have a major effect on transmission dynamics during an outbreak. One simulation estimated that by decreasing the average time to diagnosis with PCR and subsequent patient isolation from 5 days to 1 day in 60% of EBOV-infected patients, the virus attack rate (the proportion of people at risk of the infection who become infected) would drop from 80% to nearly 0% (ref.158). Consequently, in November 2014, the WHO issued a call for “rapid, sensitive, safe and simple EBOV diagnostic tests”159.

Since then, several diagnostic tests, which range from hand-held lateral flow assays to bench-top PCR-based technologies, have been developed, some of which have been evaluated and used in the field (Table 2). A mathematical model was used to evaluate the effect on EVD CFR and EBOV transmission dynamics of incorporating different diagnostic strategies that did or did not include the introduction of novel rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) in various scenarios160. A strategy that coupled novel RDTs with confirmatory PCR testing was deemed superior to the use of either PCR assays or RDTs alone and would result in a reduction of the scale of an outbreak by one-third. Whether coupling RDTs with PCR influences false-positive and false-negative designations remains to be determined. Notably, in this model, the performance characteristics of RDTs were assumed to be inferior to those of PCR assays for accurately diagnosing EVD. However, with improvement in performance, RDTs alone may replace PCR assays and alter transmission dynamics during future outbreaks. Accordingly, front-line health-care workers require training on using RDTs and reading results accurately while dressed in personal protective equipment (PPE). Until RDTs for EBOV infection are advanced with appropriate validation in their intended application setting, generally they should not be used outside known outbreak settings with low pre-test probability, owing to the increased risk of false-positive tests.

Table 2.

EBOV detection tests used in the field

| Test (manufacturer) | Test type | Target | Samples | Sensitivity | Specificity | Viruses detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid viral antigen detection tests | ||||||

| Dual Path Platform (DPP) Ebola antigen system (Chembio)a | Immunochromatographic lateral flow assay | VP40 | Venous whole blood (EDTA), venous plasma (EDTA) and capillary fingerstick whole blood | Qualitative; less sensitive than PCR; requires confirmatory testing | From limited data, does not cross-react with other ebolaviruses | EBOV |

| OraQuick Ebola rapid antigen test (OraSure Technologies)b,c | Immunochromatographic lateral flow assay | VP40 | Oral fluid and whole blood | 97.1% (from oral fluid from deceased individuals); LLOD: 53 ng per ml for whole blood samples and 106 ng per ml for oral fluid | 98–100% from venous whole blood samples; 99.1–100% from oral fluid from deceased individuals | BDBV, EBOV and SUDV; does not differentiate between ebolaviruses |

| SD Q Line Ebola Zaire Ag test (SD Biosensor)b | Immunoprecipitation lateral flow assay | GP1,2, NP and VP40 | Plasma, serum and whole blood | 84.9% for whole blood and plasma | 99.7% for whole blood and plasma | EBOV |

| PCR-based tests | ||||||

| Ebola real-time RT-PCR kit (Liferiver Bio-tech)b | Fluorescent real-time RT-PCR | Nucleic acids from ebolaviruses | Serum, body fluid and urine | LLOD: 23.9 copies of viral genome per reaction | Not available | Ebolaviruses |

| EZ1 test (DOD)a | Real-time TaqMan RT-PCR with fluorescent reporter dye detected at each PCR cycle | EBOV nucleic acids | Whole blood and plasma | Qualitative; LLOD: 100–1,000 pfu per ml depending on live or inactivated EBOV isolate and cycler used | 100%; no cross-reactivity with other ebolaviruses or marburgviruses | EBOV |

| FilmArray NGDS BT-E (BioFire)a | Fluorescent nested multiplex RT-PCR | EBOV nucleic acids | Whole blood, plasma and serum | LLOD: 1,000 pfu per ml or 4.36 × 103 genome equivalentsd per ml for live virus | EBOV; no cross-reactivity with other ebolaviruses or marburgviruses | EBOV |

| FilmArray Biothreat-E (BioFire)a | Fluorescent nested multiplex RT-PCR | EBOV nucleic acids | Whole blood and urine | 95% detection rate confirms LOD; LOD: 6 × 105 pfu per ml using γ-irradiated EBOV | 89–100% using whole blood samples, depending on the study population (Sierra Leone and UK) | EBOV |

| Idylla Ebola virus triage test (Biocartis)a | Qualitative real-time RT-PCR with fluorescent reporter dyes generated upon amplification of cDNA | EBOV and SUDV nucleic acids | Whole blood and urine | 97% positive agreement compared with a non-reference standard; LLOD: 465 pfu per ml or 178 copies per ml | 100% for EBOV | EBOV and SUDV |

| LightMix Ebola Zaire TIB MolBio with Lightcycler (Roche)a | Qualitative real-time RT-PCR with fluorescent reporter dye detected at each PCR cycle | EBOV nucleic acids | Whole blood | 95% positive agreement compared with a non-reference standard; LLOD: 4,781 pfu per ml | 100% for EBOV | EBOV |

| Ebola virus NP real-time RT-PCR (ThermoFisher (CDC))a | Qualitative real-time RT-PCR with fluorescent reporter dye detected at each PCR cycle | EBOV NP RNA | Whole blood, serum, plasma and urinee | 99.80%; LLOD: 600–700 TCID50 copies per ml | 100% for EBOV | EBOV |

| RealStar Ebolavirus RT-PCR kit (Altona Diagnostics)a,b | Real-time RT-PCR with fluorescent dye-labelled probes to detect PCR amplicons | Nucleic acids from ebolaviruses | Plasma | 82%; LLOD: 1 pfu per ml | 100% for EBOV | Ebolaviruses |

| EBOV VP40 real-time RT-PCR (CDC)a | Real-time RT-PCR with fluorescent dye-labelled probes to detect PCR amplicons | EBOV VP40 RNA | Whole blood, serum, plasma and urinee | LLOD: 400–600 TCID50 per ml from whole blood; 250–600 TCID50 per ml, depending on body fluid sample and extraction method used | 100% for EBOV | EBOV |

| Gene Xpert Ebola (Cepheid)a,b | Real-time RT-PCR with fluorescent signal from probes for quality control | EBOV NP and GP nucleic acids | Whole blood and oral fluids | 100%; LLOD: 232.4 genomic copies per ml | 99.5% from whole blood; 100% from oral fluid | EBOV |

BDBV, Bundibugyo virus; CDC, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DOD, US Department of Defense; EBOV, Ebola virus; GP, glycoprotein; LLOD, lower limit of detection; LOD, limit of detection; NP, nucleoprotein; pfu: plaque-forming units; RT-PCR, PCR with reverse transcription; SUDV, Sudan virus; TCID50, 50% tissue culture infective dose (concentration at which 50% of cultured cells are infected with a diluted solution of viral fluid); VP40, viral protein 40. aEmergency use authorization approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). bEmergency use authorization approved by the WHO. cApproved by the FDA.; dGenome equivalents are calculated by converting the length of a genome in base pairs to micrograms of RNA. eShould not be the only specimen tested. Adapted from ref.288.

Importantly, disease severity, disease acuity and sample material need to be taken into consideration before choosing a particular diagnostic test. In general, blood is the sample material of choice for live patients, whereas oropharyngeal swabs are useful for post-mortem diagnosis. The diagnostic test of choice in the acutely ill individual with suspected EVD is a PCR-based assay of a blood sample targeting one or more of the EBOV genes. In the context of the ongoing outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, diagnosis relies on the Cepheid Gene Xpert platform targeting EBOV GP and EBOV NP (Table 2). With widespread use of the same platform in multiple field laboratories in the Democratic Republic of the Congo comparison is easier across patients and outbreak samples. Regardless of the platform, a general principle is that a diagnostic strategy targeting only one EBOV gene needs to be repeated for confirmation, whereas strategies utilizing two targets do not require repeating. Asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic EBOV-infected people may not have viraemia titres detectable by PCR assays, but typically have detectable IgG and IgM responses ~3 weeks after infection. Appropriate serological testing to confirm the presence of anti-EBOV IgG antibodies would be indicated in this setting. Of note, antibody responses may not reliably develop or may be delayed in acutely symptomatic patients with EVD. Thus, PCR-based testing is optimal in the acutely ill patient (from blood samples) and also for detection of EBOV RNA in amniotic fluid, breast milk, ocular fluid, saliva, seminal fluid, stool, sweat, tears, urine and vaginal fluid even after blood samples begin to test negative36,40,57,134,161,162.

Prevention

The overall strategy for mitigating the spread of an ongoing EVD outbreak is to interrupt community and nosocomial transmission of EBOV from patients to susceptible individuals. Effectively achieving this outcome depends upon the quality of measures in place; ideally, interruption of the chain of transmission in the community can be achieved by anthropological and sociological measures (Box 1); isolating individuals with suspected, probable or confirmed EVD for care (which includes contact tracing and following-up over 21 days); and treatment in an ETU or holding centre. The crucial importance of contact tracing is illustrated by the backdrop of the current EVD outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where a longstanding conflict has impeded maximal tracing of contacts of patients with EVD, and violent incursions in outbreak areas are associated with increases in estimated EBOV transmission rates163. In a mathematical model estimating changes in EBOV transmission in 12 districts in Sierra Leone from June 2014 to February 2015, introduction of additional treatment beds within the area to isolate patients with suspected or confirmed EVD would have theoretically averted ~56,000 new EVD cases164. The risk of nosocomial transmission can be reduced by isolation of patients with suspected, probable or confirmed EVD, the use of appropriate PPE, strategies for donning and doffing PPE and strict adherence to infection prevention and control practices. Such practices include the provision of dedicated or disposable patient care equipment, safe injection practices, hand hygiene and attention to environmental infection control.

The provision of guidelines for discharge criteria is an important aspect of clinical care to avoid subsequent transmission events in the community. During the 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak, the WHO recommended that patients diagnosed with EVD can be considered for discharge from health-care facilities if ≥3 days have elapsed since resolution of clinical signs, if they show appreciable improvement in clinical condition, if they are able to perform activities of daily living and if a blood sample is negative for EBOV RNA (detected with RT-PCR tests) from the third day of the patient becoming asymptomatic. Patients with unresolved signs and symptoms should be discharged after two negative blood test results (48 h apart), and in these patients an alternative diagnosis should be sought that may explain the lack of clinical improvement165. Other health authorities (such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) have created recommendations for the discharge of patients under investigation. In most patients with EVD managed in the USA and Europe during the 2013‒2016 Western African outbreak, repeatedly negative RT-PCR tests of blood samples was the primary criterion used for discharge, along with symptomatic improvement. However, in several centres in the USA and Europe, other criteria were used, including RT-PCR tests of samples of other bodily fluids and EBOV cell culture under biosafety level 4 containment166.

The time-limited detection of infectious EBOV (by PCR and viral culture) and long-term detection of EBOV RNA in the semen of male survivors were only possible in large numbers in the 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak. Rare but consequential sexual transmission events have also been documented37,41,66,131. Accordingly, WHO recommendations167 (currently being updated) for the prevention of sexual transmission from survivors include routine PCR testing of semen beginning at 3 months after health-care facility discharge (as the semen should be assumed to be infectious for the first 3 months) and until two consecutive semen samples taken at least 1 week apart are negative. Abstinence or safe sexual practices should be implemented for the same period or for at least 1 year.

Candidate vaccines

Amid increasing concerns about unmitigated transmission during the 2013–2016 Western African EVD outbreak in mid-2014, a statement from a stakeholder meetings held by the WHO urged acceleration of the development and evaluation of EVD candidate vaccines. As the EBOV glycoprotein GP1,2 is the major viral immunogen, all candidate vaccines in advanced development are designed to stimulate a host immune response against this protein, among others. In the Western African outbreak, several candidate vaccines were evaluated in clinical trials168,169 (Table 3). Owing to the success of the Ebola ça Suffit! phase III ring vaccination trial in Guinea124,125, the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP, a live-attenuated recombinant vesiculovirus candidate vaccine currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Commission and is actively administered to help contain the currently ongoing EVD epidemic that started in Nord-Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2018. Using a ring vaccination strategy, whereby contacts of infected individuals (primary ring) and contacts of those contacts (secondary ring) are vaccinated, this candidate vaccine has been administered to 276,520 people in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo as of 26 January 2020 (ref.22). Preliminary analyses on data evaluating the first 93,965 vaccinated individuals revealed a lower estimated attack rate among individuals who were vaccinated (0.017%) than in unvaccinated individuals (0.656%)170. The WHO reported an estimated vaccine efficacy of 97.5% (95% CI 95.8–98.5%)170. However, determination of true vaccine efficacy is impossible in the absence of a placebo-controlled group. Notably, a model of the EBOV infection risk during the 2018 EVD outbreak in Équateur Province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo found that the introduction of ring vaccination with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine resulted in a decrease of 70.4% of the geographical area of risk and 70.1% of the level of EBOV infection risk. However, if ring vaccination is delayed by as little as 1 week, the size of this effect is considerably diminished171. The same candidate vaccine is also used in the ongoing outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo as emergency post-EBOV exposure prophylaxis in, for instance, health-care workers.

Table 3.

EVD candidate vaccines in phase I–III clinical trials

| Candidate vaccine(s) | Vaccine design | Study design | Outcomes | Results | Notes | Trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (also known as BPSC-1001 and V920) | Replication-competent rVSIV expressing EBOV GP1,2 in place of VSIV G | Phase I trial evaluating safety and immunogenicity of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP escalating doses | Primary: adverse effects up to 6 months. Secondary: humoral immunity up to 6 months | No pre-existing immunity; anti-EBOV matrix antibodies detected in 28% of participants, with levels that peaked at day 56 after vaccination289; neutralizing antibodies persisted for 6 months | Adverse effects: arthralgia, oligoarthritis, myalgia, headache and injection site pain | NCT02283099 |

| rAd26 ZEBOV-GP and MVA-BN-Filo | Replication-defective human adenovirus (Ad) 26 vector expressing EBOV GP1,2; replication-incompetent modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) Bavarian Nordic (BN) expressing EBOV, SUDV, MARV and TAFV GP1,2 | Phase I trial evaluating safety and immunogenicity of MVA-BN-Filo and rAd26 ZEBOV-GP as heterologous prime-boost vaccine regimens | Primary: adverse effects up to 78 days. Secondary: immune responses up to 1 year | Anti-EBOV GP antibodies detected in 97% or 23% of participants receiving rAd26 ZEBOV-GP or MVA-BN-Filo, respectively, at 28 days after primary vaccination; all participants had specific IgG response at 21 days after the boost and at 8 months290 | Adverse effects: with rAd26 ZEBOV-GP: fever, injection site reactions headache, myalgia, nausea, fatigue and chills; with MVA-BN-Filo: injection site reactions, fatigue, headache, myalgia, chills, nausea, arthralgia, pruritus and rash | NCT02313077 |

| rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (also known as BPSC-1001 and V920) | Replication-competent rVSIV expressing EBOV GP1,2 in place of VSIV G | Phase I/II trial evaluating safety and tolerability of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP at low (3 × 105 pfu) or high (1–5 × 107 pfu) dose in health-care workers | Primary: adverse effects up to 14 days. Secondary: viraemia for 7 days, persistent titres of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP-specific IgG antibodies at 168 days, neutralizing antibodies and rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP viral shedding up to 7 days291 | Anti-EBOV-GP binding and neutralizing antibody titres were lower in the low-dose group than in the high-dose group | Adverse effects: fever, myalgia and chills; oligoarthritis, maculopapular rash and vascular dermatitis in the low-dose group | NCT02287480, conducted in Switzerland |

| rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (also known as BPSC-1001 and V920) or ChAd3-EBOZ | Replication-competent rVSIV expressing EBOV GP1,2 in place of VSIV G; ChAd3 vector expressing EBOV GP1,2 | Phase II trial comparison of vaccines and placebo | Primary outcome: serious adverse effects occurring within 30 days | With rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP: malaria, injection site reactions, headache, muscle pain, fever and fatigue | With rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP: geometric mean antibody titre maintained at 12 months at 800 ELISA units per ml | NCT02344407, also known as PREVAIL I, conducted in Liberia292 |

| rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (also known as BPSC-1001 and V920) | Replication-competent rVSIV expressing EBOV GP1,2 in place of VSIV G | Phase II/III trial. Arm 1: immediate IM vaccination in patients with suspected EVD within 7 days of enrolment. Arm 2: deferred IM vaccination 18–24 weeks following enrolment, then crossed over to immediate vaccination group and monitored for 6 additional months | Primary: incidence of confirmed EBOV infections at >21 days after vaccination. Secondary: confirmed EBOV infections during 6 months following vaccination | No confirmed EBOV infections occurred; no efficacy analysis performed | Adverse events: fever, headache, fatigue, joint pain, rash and mouth ulcers293 | NCT02378753, also known as STRIVE, conducted in Sierra Leone |

| rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (also known as BPSC-1001 and V920) | Replication-competent rVSIV expressing EBOV GP1,2 in place of VSIV G | Single-arm, phase IIIb study of ring vaccination (immediate and delayed) of contacts and contacts of contacts, given immediately after laboratory confirmation of initial case or after a delay of 21 days | Primary: number of patients with EVD amongst vaccinated (immediate and delayed) individuals. Secondary: assessment of safety 84 days after vaccination | No EVD cases within 10 days after immediate vaccination124; in delayed vaccination group, 23 patients with EVD out of 4,507 contacts | Adverse effects: headache, muscle pain, fever and anaphylaxis; potential neurotropism of VSIV may persist despite substitution of G with EBOV GP1,2294,295 | NCT03161366 and Ebola ça Suffit! trial |

| rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (also known as BPSC-1001 and V920) | Replication-competent rVSIV expressing EBOV GP1,2 in place of VSIV G | Phase III trial evaluating safety and immunogenicity of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP in healthy adults | Primary: determination of geometric mean titre of anti-EBOV GP1,2 antibodies at 28 days after vaccination and selected adverse events | Geometric mean titre of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (measured with ELISA) increased on day 28 and persisted through 24 months296; geometric mean titres of neutralizing antibodies peaked at 18 months and maintained at 24 months | Adverse effects: arthralgia and arthritis | NCT02503202 |

| rAd26 ZEBOV-GP and MVA-BN-Filo | Replication-defective human Ad 26 vector expressing EBOV GP1,2; replication-incompetent MVA-BN expressing EBOV, SUDV, MARV and TAFV GP1,2 | Phase III trial evaluating safety and immunogenicity of rAd26 ZEBOV-GP, MVA-BN-Filo boost 56 days after first vaccination and a second boost with rAd26 ZEBOV-GP given 2 years after the first vaccination | Primary: number of participants with adverse effects. Secondary: number of participants with adverse effects following the MVA-BN-Filo boost; serum concentrations of antibodies binding to EBOV GP1,2 after the MVA-BN-Filo boost | No efficacy data available as the outbreak in Sierra Leone ended before efficacy could be determined | Preliminary safety and immunogenicity follow-up data from EBOVAC Salone trial indicate that the vaccine regimen is well tolerated and produces immune responses up to 2 years after vaccination | NCT02509494, also known as EBOVAC-Salone |

| rAd26 ZEBOV-GP and MVA-BN-Filo | Replication-defective human Ad 26 vector expressing EBOV GP1,2; replication-incompetent MVA-BN expressing EBOV, SUDV, MARV and TAFV GP1,2 | Long-term safety and immunogenicity evaluation of previously vaccinated individuals. Cohort 1: participants who received at least a primary vaccination with rAd26 ZEBOV-GP and, if applicable, a MVA-BN-Filo boost 56 days after primary vaccination in healthy participants of ≥1 year of age. Cohort 2: infants conceived by participants in the 3 months following primary vaccination or 28 days following MVA-BN-Filo boost | Primary: number of participants with serious adverse effects and serum concentrations of EBOV GP1,2 up to 4–5 years following primary vaccination; in infants conceived during the trial, number of serious adverse effects from birth through 5 years of age. Secondary: anti-EBOV GP1,2 neutralizing antibodies 4–5 years after primary vaccination; effect of previous infection with Plasmodium spp. on persistence of humoral immune response to vaccination | Preliminary immunogenicity data indicate vaccine regimen produces immune responses up to 2 years after vaccination | Preliminary safety data indicate that the vaccine regimen is well tolerated | NCT03820739, also known as EBOVAC-Salone extension |