Abstract

Abstract

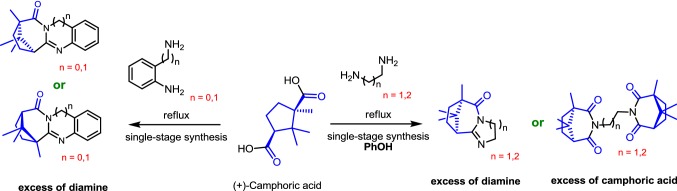

An effective technique for one-stage synthesis of new polycyclic nitrogen-containing compounds has been developed. The procedure involves refluxing mixtures of camphoric acid with aliphatic or aromatic diamine without catalysts. In cases where the starting amine has a low boiling point (less than 200 °C), phenol is used as a solvent, as it is the most optimal one for obtaining products with good yields. It has been shown that the use of Lewis acids as catalysts reduces the yield of the reaction products. A set of compounds have been synthesized, which can be attributed to synthetic analogues of alkaloids. In vitro screening for activity influenza virus A was carried out for the obtained compounds. The synthesized quinazoline-like agent 14 has inhibitory activity against different strains of influenza viruses.

Graphical abstract

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11030-019-09932-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: (+)-Camphoric acid, Single-stage synthesis, Alkaloid analogues, Influenza virus, Antiviral activity, Antivirals

Introduction

Influenza represents one of the most serious challenges to medical science and health care all over the world. It causes annual epidemics and from time to time pandemics, both resulting in significant increase in morbidity and mortality [1]. Due to fast replicative cycle, ability to reassort the fragments of segmented genome and lack of correcting activity of viral polymerase influenza virus can quickly select mutants that do not match the virus-inhibiting antibodies and can therefore escape from the immune response [2]. Several classes of chemically distinct compounds are currently used for treatment of influenza: amantadine and rimantadine (two blockers of M2 proton channel) [3, 4], four neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir, zanamivir, peramivir and laninamivir) prevent budding of viral progeny [5], umifenovir (Arbidol) is used against influenza in Russia and China [6, 7], pyrazinecarboxamide derivative favipiravir (T-705) was approved for stockpiling for potential treatment of pandemic influenza [8, 9], and baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza®) that has been recently approved by FDA interferes with endonuclease activity of viral PA subunit of polymerase complex [10].

The same features of influenza virus that cause the emergence of antibody-escape mutants lead also to the selection of drug resistance to direct-acting antivirals. Indeed, all current isolates of influenza virus are resistant to adamantane derivatives so that WHO does not recommend their use for treatment of influenza anymore [10–12]. In 2007–2009 almost total resistance of seasonal influenza A(H1N1) viruses to oseltamivir was achieved. These strains were further replaced with oseltamivir-susceptible pandemic influenza viruses A(H1N1)pdm09 [13, 14]. Taken together, these facts suggest that novel anti-influenza drugs of alternative mechanism(s) of activity and viral target(s) are therefore of high priority for medicinal science and health care.

The abundance, crystallinity and variety of transformations of (+)-camphor were interesting throughout the history of organic chemistry. Our work is devoted to the investigation of chemical properties of (+)-camphoric acid (product of oxidation of (+)-camphor). Camphoric acid is a cyclopentane derivative containing two carboxylic acid functional groups on the first and third carbon atoms. The C-1 atom has an additional methyl group, thereby converting camphoric acid into an enantiomeric ditopic organic linker with different coordination regimes. Moreover, the coordination chemistry of camphoric acid specifically gives rise to many interesting chiral features applicable to both materials and life sciences, such as asymmetrical synthesis or crystallization, homochiral structural design, chiral induction, absolute helical control and ligand handedness [15]. There are examples of the use of camphoric acid derivatives as ligands [16–18].

The condensation of carboxylic acids with amines and anilines is known to be a classical way of preparing amides. This interaction is shown for a wide spectrum of various substrates [19]. The methods for preparing 2-substituted benzimidazoles based on direct cyclocondensations of carboxylic acids with benzene-1,2-diamine are also well known, but almost all of them involve rigid conditions, high temperatures or acidic conditions [20–22]. For example, many carboxylic acids are condensed with benzene-1,2-diamine at temperatures of about 200° [23–25].

Thus, we consider it relevant to study the interaction of camphoric acid with various aliphatic and aromatic diamines. This study is important, because all nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds play a great role in medicinal and organic chemistry in whole.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

The present work is devoted to the synthesis of new polycyclic nitrogen-containing compounds from (+)-camphoric acid and aliphatic or aromatic diamines. The first investigated reaction was interaction between ethylenediamine 2 and (+)-camphoric acid 1. As a result of refluxing 1 eq. camphoric acid with 2 eq. ethylenediamine in phenol, product 3 was obtained (Scheme 1). This technique led to an almost quantitative conversion to 3 after 2 h with 80% yield. Product 3 was not observed, if refluxing the starting reagents was carried out without a solvent, apparently due to the low boiling point of the starting amine 2. Also we used toluene, DMSO and o-xylene as a solvent for this interaction. It should be noted that using toluene or xylene significantly increased the conversion time to 24 h. The use of DMSO as a solvent resulted in a double decrease in the desired product. Thus, using phenol as a solvent proved to be the most optimal for the production of the tricyclic product 3.

Scheme 1.

Interaction of camphoric acid with aliphatic diamines

Refluxing a tenfold excess of camphoric acid with diamine 2 in i-PrOH gives us a mixture of cyclic amide of symmetrical structure 4 and product 3 (1:1). Product 4 was purified by column chromatography and isolated with 9% yield.

Further, the interaction of 1,3-diaminopropane 5 with camphoric acid was investigated. Refluxing 5 with 1 in phenol for 3 h led to compound 6 with 90% yield (Scheme 1). Unfortunately, we were unable to isolate the cyclic amide of a symmetric structure based on 1,3-diaminopropane.

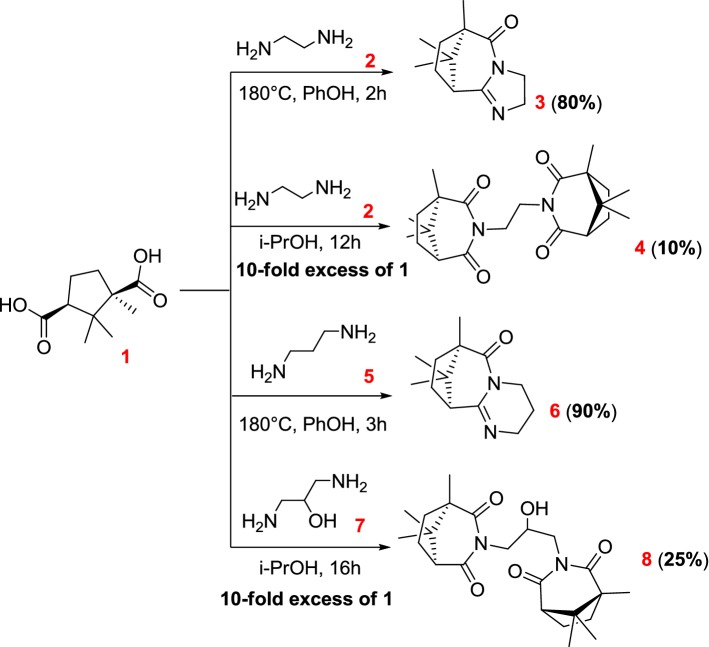

Product 8 was obtained by refluxing 1 with 7 in an i-PrOH with 25% yield. This interaction allows us to obtain compound 8 and presumably mixture of polycyclic compounds with a similar structure to the compound 6, which, unfortunately, are not received in a pure form. For compounds 3, 8 and perchlorate of the compound 6 (6·HClO4) X-ray crystallographic analysis was carried out (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Crystallographic data (excluding structure factors) for the structures 3, 6*HClO4, 10a, 14, 8 in this paper have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (Deposition Nos. CCDC 1838812-1838815 and 1874453) as supplementary publication

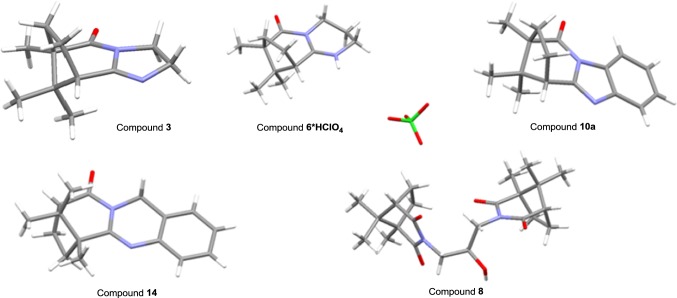

Then, we decided to investigate the possibility of obtaining compounds of a similar structure from aromatic amines. Thus, o-phenylenediamine 9 was chosen as the next object of our research.

We show that refluxing of mixture of 9 with 1 without a solvent for 3 h leads to the formation of a mixture of two benzimidazole derivatives 10a and 10b with a total yield of 70% (Scheme 2). In this case, we carried out a study of the conversion rate and the ratio of the final products, by replacing camphoric acid 1 with its anhydride, and also by adding 5 mol% of Lewis acid to the reaction mixture, for example, anhydrous zinc chloride. It is shown that the use of the Lewis acid increases the conversion time from 3 to 5 h and decreases the total yield of the reaction products to 55% and the quantity of the major isomer 10a in the final mixture. Using camphoric acid anhydride as a starting reagent slightly reduces the overall yield of the reaction products. Compounds 10a and 10b have been isolated after the column chromatography with a yield of 40% and 2%, respectively. The structure of compound 10a has been confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis (Fig. 1).

Scheme 2.

Interaction of camphoric acid with aromatic diamines

The benzimidazole derivative 10a was previously described [19]. The procedure involved refluxing the mixture of reagents with 10 mol% of boric acid in toluene for 48 h, and a Dean–Stark trap was used for the azeotropic removal of H2O. We have also shown the possibility of synthesizing compound 10a by single-stage synthesis without solvent and catalysts, which significantly reduced the reaction time.

Then, we chose naphthalene-1,8-diamine 11 as parent aromatic diamine. Refluxing double excess of 11 with 1 without a solvent for 6 h led to the mixture of compounds 12a and 12b with a total yield of 50% (Scheme 2). Compounds 12a and 12b have been isolated by column chromatography with a yield of 30% and 2%, respectively. We consider that the minor product in all the transformations above is obtained by the primary nucleophilic attack to a more sterically hindered carboxylic group. This assumption is confirmed by 1H, 13C and 2D NMR spectra (see Supporting Information).

Also, the interaction of o-aminobenzylamine 13 with 1 was studied. Refluxing the mixture of 1 and excess of 13 without a solvent for 4 h resulted in compound 14 with 45% yield (Scheme 2). X-ray crystallographic analysis shows that, in this case, the main product is the compound formed as a result of the primary nucleophilic attack to a more sterically hindered carboxyl group (Fig. 1).

Biological part

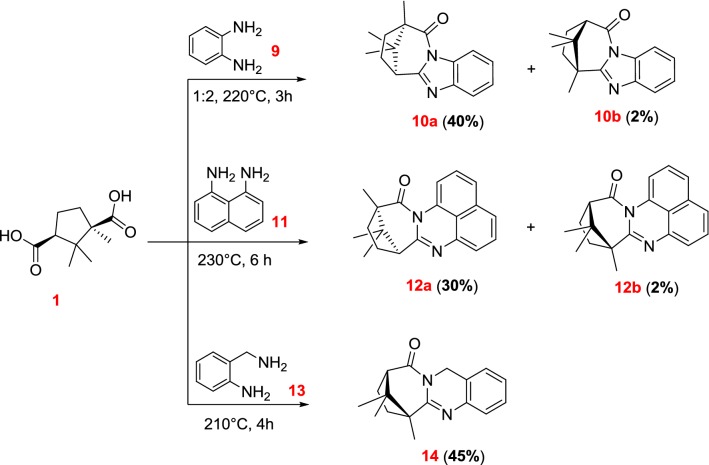

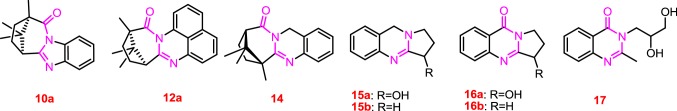

Synthesized polycyclic nitrogen-containing compounds 3, 6, 10a, 10b, 12a, 12b, 14 can be referred to as synthetic analogues of natural quinazoline alkaloids. Nowadays, natural and synthetic quinazolines attract considerable attention due to their diverse and sometimes very high biological activity [26]. For example, the most common active metabolites of plants of the genus Peganum are quinazoline alkaloids (such as vasicine 15a, desoxyvasicine 15b, vasicinone 16a, deoxyvasicinone 16b [27]). These natural compounds have a broad spectrum of native biological activity, in particular: anti-AD for 15a–b [28], anti-parasitic for 16a–b [29], insecticidal for 15a [30]. At the same time, synthetic derivative of quinazoline diproqualone 17 was previously used as an analgesic for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis [31] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Similarity of the structure of quinazoline alkaloids and synthesized compounds

Along with the pronounced biological activity, the compounds of the quinazoline series can be successfully used as chiral catalysts [32, 33]. Thus, the use of vasicine 15a as an organic catalyst for direct C-H arylation of unactivated arenes with aryl iodides/bromides without assistance of any transition metal catalyst has been described [34]. Vasicine 15a, a quinazoline alkaloid, from the leaves of Adhatoda vasica, has been utilized as an efficient catalyst for metal- and base-free Henry reaction of various aldehydes with nitro alkanes [35]. The quinazoline structure possibly imparts rigidity to the ligand and hence consistently high enantioselectivity [36]. At present time, attention of numerous groups is being paid to the synthesis of analogues of natural alkaloids.

Antiviral activity

Synthetic and natural quinazoline alkaloids can exhibit pronounced antiviral properties [37, 38]. The compounds synthesized in this work contain both the monoterpenic fragment and the N-heterocycle. We have previously shown that various derivatives of monoterpenoids, in particular compounds including a 1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptane scaffold and N-heterocyclic fragment, exhibit antiviral properties against the influenza virus [39, 40]. In this regard, the obtained derivatives were screened for their inhibitory activity against influenza virus A H1N1. For each compound, the values of 50% cytotoxic dose (CC50), 50% virus-inhibiting dose (IC50) and selectivity index (SI) were calculated. The results are shown in Table 1. Adamantane- and norbornane-based derivatives were used as reference compounds due to their close similarity to the compounds under investigation in having rigid cage fragments in their structures. It is worth noting that compounds 3, 6, 10b, 12b, 14 are less cytotoxic than reference compounds. Compounds 3, 6, 10b, 14 are most effective in inhibiting the influenza virus A (H1N1) and can be used for further studies this type of activity. We believe that aliphatic polycyclic compounds (with a similar structure to compounds 3, 6) or compounds containing an additional aromatic cycle may exhibit potentially high antiviral activity, but in this case, we are particularly interested in the isomers with the hem-dimethyl bridge directed upwards.

Table 1.

Antiviral activity of compounds 3, 4, 6, 10a, 12a–b, 14 against influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1)

| Entry | Compound | CCa50 (µM) | ICb50 (µM) | SIc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | > 1456.3 | 51.5 ± 6.0 | 28 |

| 2 | 4 | > 772.2 | > 772.2 | 1 |

| 3 | 6 | > 1361.7 | 36.8 ± 4.1 | 37 |

| 4 | 10a | 264.2 ± 2.2 | 43.3 ± 3.2 | 6 |

| 5 | 10b | 1179.6 ± 91.2 | 55.1 ± 6.1 | 21 |

| 6 | 12a | 136.7 ± 10.8 | 18.7 ± 1.9 | 7 |

| 7 | 12b | > 985.6 | > 985.6 | 1 |

| 8 | 14 | >1117.9 | 17.9 ± 2.0 | 62 |

| 9 | Rimantadine | 374 ± 26 | 61 ± 5 | 6 |

| 10 | Amantadine | 329 ± 21 | 60 ± 7 | 5 |

| 11 | Deitiforin | 956 ± 68 | 142 ± 11 | 7 |

aCC50—cytotoxic concentration; the concentration resulting in 50% death of cells

bIC50—effective concentration; the concentration resulting in 50% inhibition of virus replication

cSI—selectivity index, ratio CC50/IC50

For compound 14, which showed the highest activity, we studied the antiviral activity against different strains of influenza virus (Table 2). It has been shown that compound 14 has inhibitory activity against different strains of influenza virus A. The compound synthesized has inhibitory activity against strain H5N2 (comparable to reference compounds) and strain H1N1 (exceeding that of reference compounds). Unfortunately, the inhibitory activity of compound 14 against strain H3N2 is lower than that of the reference compounds.

Table 2.

Antiviral activity of compound 14 and reference standards

| Compound | CC50 (µM) | Antiviral activity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) | A/Aichi/2/68 (H3N2) | A/mallard/Pennsylvania (H5N2) | |||||

| IC50 (µM) | SI | IC50 (µM) | SI | IC50 (µM) | SI | ||

| 14 | > 1118 | 18 ± 2 | 62 | 27 ± 4 | 41 | 21 ± 3 | 53 |

| Rimantadine | 374 ± 26 | 61 ± 5 | 6 | 5 ± 1 | 75 | 7 ± 2 | 53 |

| Amantadine | 329 ± 21 | 60 ± 7 | 5 | 4 ± 0 | 82 | 6 ± 1 | 55 |

| Deitiforin | 956 ± 68 | 142 ± 11 | 7 | 17 ± 2 | 56 | 19 | 50 |

Conclusion

In conclusion, a simple and effective method of single-stage synthesis of polycyclic nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds, synthetic analogues of natural alkaloids, is suggested for the first time. It was shown that the optimal technique of synthesis is refluxing mixtures of parent compounds in phenol or without solvent and catalysts. Using this method, we synthesized a number of polycyclic amides containing in their structure both a heterocyclic fragment and a bicyclic fragment (3, 6, 10a, 10b, 12a, 12b, 14) and two cyclic symmetrical amides (4, 8). The structures of all synthesized compounds were confirmed by a complete set of spectral data, including X-ray crystallographic analyses of crystalline products 3, 6, 8, 10a and 14. In vitro screening for inhibitory activity against influenza virus was carried out for the obtained compounds and compound 14, was shown, exhibits inhibitory activity against different strains of influenza virus A (H1N1, H3N2, H5N2). Compounds 3, 6, 10b and their derivatives, in turn, can be used in the further study of this type of activity.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (18-03-00271 A).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (2016) Media centre influenza (seasonal) fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal)

- 2.Lowen AC. Constraints, drivers, and implications of influenza A virus reassortment. Annu Rev Virol. 2017;4:105–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-101416-041726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang R, Li H, Swanson JM, Jr, Voth GA. Multiscale simulation reveals a multifaceted mechanism of proton permeation through the influenza A M2 proton channel. PNAS. 2014;111:9396–9401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401997111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong M, DeGrado WF. Structural basis for proton conduction and inhibition by the influenza M2 protein. Protein Soc. 2012;21:1620–1633. doi: 10.1002/pro.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ison MG. Antiviral treatments. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaising J, Polyak SJ, Pécheur EI. Arbidol as a broad-spectrum antiviral: an update. Antiviral Res. 2014;107:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boriskin YS, Leneva IA, Pécheur EI, Polyak SJ. Arbidol: a broad-spectrum antiviral compound that blocks viral fusion. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:997–1005. doi: 10.2174/092986708784049658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delang L, Abdelnabi R, Neyts J. Favipiravir as a potential countermeasure against neglected and emerging RNA viruses. Antiviral Res. 2018;153:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuta Y, Komeno T, Nakamura T. Favipiravir (T-705), a broad spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B. 2017;93:449–463. doi: 10.2183/pjab.93.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Hirotsu N, Lee N, de Jong MD, Hurt AC, Ishida T, Sekino H, Yamada K, Portsmouth S, Kawaguchi K, Shishido T, Arai M, Tsuchiya K, Uehara T, Watanabe A. Baloxavir marboxil investigators group baloxavir marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. NEJM. 2018;6(379):913–923. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bright RA, Shay DK, Shu B, Cox NJ, Klimov AI. Adamantane resistance among influenza A viruses isolated early during the 2005–2006 influenza season in the United States. JAMA. 2006;295:891–894. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.8.joc60020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson MI, Simonsen L, Viboud C, Miller MA, Holmes EC. The origin and global emergence of adamantane resistant A/H3N2 influenza viruses. Virology. 2009;388:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason S, Devincenzo JP, Toovey S, Wu JZ, Whitley RJ. Comparison of antiviral resistance across acute and chronic viral infections. Antiviral Res. 2018;158:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain M, Galvin HD, Haw TY, Nutsford AN, Husain M. Drug resistance in influenza A virus: the epidemiology and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2017;10:121–134. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S105473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu Z, Zhan C, Zhang J, Bu X. Chiral chemistry of metal–camphorate frameworks. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:3122–3144. doi: 10.1039/C6CS00051G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murtinho D, Ogihara CH, Serra MES. Novel tridentate ligands derived from (+)-camphoric acid for enantioselective ethylation of aromatic aldehydes. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2015;26:1256–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2015.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serra MES, Murtinho D, Paz V. Enantioselective alkylation of aromatic aldehydes with (+)-camphoric acid derived chiral 1,3-diamine ligands. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2017;28:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2017.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He K, Zhou Z, Wang L, Li K, Zhao G, Zhou Q, Tang C. Synthesis of some new chiral bifunctional o-hydroxyarylphosphonodiamides and their application as ligands in Ti(IV) complex catalyzed asymmetric silylcyanation of aromatic aldehydes. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:10505–10513. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2004.08.082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maras N, Kocevar M. Boric acid-catalyzed direct condensation of carboxylic acids with benzene-1,2-diamine into benzimidazoles. Helv Chim Acta. 2011;94:1860–1874. doi: 10.1002/hlca.201100064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alamgir M, Black DSC, Kumar N. Synthesis, reactivity and biological activity of benzimidazoles. Top Heterocycl Chem. 2007;9:87–118. doi: 10.1007/7081_2007_088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai R, Wei Z, Liu J, Xie W, Yao H, Wu X, Jiang J, Wang Q, Xu J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 4′-[(benzimidazole-1-yl)methyl]biphenyl-2-sulfonamide derivatives as dual angiotensin II/endothelin A receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:4661–4667. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singla P, Luxami V, Singh R, Tandon V, Paul K. Novel pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine with 4-(1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)-phenylamine as broad spectrum anticancer agents: synthesis, cell based assay, topoisomerase inhibition, DNA intercalation and bovine serum albumin studies. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;126:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen X, El Bakali J, Deprez-Poulain R, Deprez B. Efficient propylphosphonic anhydride (®T3P) mediated synthesis of benzothiazoles, benzoxazoles and benzimidazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:2440–2443. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obermayer D, Damm M, Kappe CO. Simulating microwave chemistry in a resistance-heated autoclave made of semiconducting silicon carbide ceramic. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:15827–15830. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krause M, Foks H, Augustynowicz-Kopeć E, Napiórkowska A, Szczesio M, Gobis K. Synthesis and tuberculostatic activity evaluation of novel benzazoles with alkyl. Cycloalkyl Pyridine Moiety Mol. 2018;23:985. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang D, Gao F. Quinazoline derivatives: synthesis and bioactivities. Chem Cent J. 2013;7:95. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-7-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asgarpanah J, Ramezanloo F. Chemistry, pharmacology and medicinal properties of Peganum harmala L. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;6:1573–1580. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu W, Yang YD, Cheng XM, Cong C, Shuping L, Dandan H, Li Y, Zhengtao W, Changhong W. Rapid and sensitive detection of the inhibitive activities of acetyl- and butyryl-cholinesterases inhibitors by UPLC–ESI-MS/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2014;94:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astulla A, Zaima K, Matsuno Y, Hirasawa Y, Ekasari W, Widyawaruyanti A, Zaini NC, Morita H. Alkaloids from the seeds of Peganum harmala showing antiplasmodial and vasorelaxant activities. J Nat Med. 2008;62:470–472. doi: 10.1007/s11418-008-0259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nenaah G. Toxicity and growth inhibitory activities of methanol extract and the β-carboline alkaloids of Peganum harmala L. against two coleopteran stored-grain pests. J Stored Prod Res. 2011;47:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jspr.2011.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arora R, Kapoor A, Gill NS, Rana AC. Quinazolinone: an overview. IRJP. 2011;2:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Çakıcı M, Kılıç H, Ulukanlı S, Ekinci D. Evidence for involvement of cationic intermediate in epoxidation of chiral allylic alcohols and unfunctionalised alkenes catalysed by MnIII(quinazolinone) complexes. Tetrahedron. 2018;74:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2017.11.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karabuga S, Karakaya I, Ulukanli S. 3-Aminoquinazolinones as chiral ligands in catalytic enantioselective diethylzinc and phenylacetylene addition to aldehydes. Tetrahedron Assymetry. 2014;25:851–855. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2014.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma S, Kumar M, Kumar V, Kumar N. Vasicine catalyzed direct C–H arylation of unactivated arenes: organocatalytic application of an abundant alkaloid. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:4868–4871. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.06.125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma S, Kumar M, Bhatt V, Nayal OS, Thakur MS, Kumar N, Singh B, Sharma U. Vasicine from Adhatoda vasica as an organocatalyst for metal-free Henry reaction and reductive heterocyclization of o-nitroacylbenzenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016;57:5003–5008. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.09.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aga MA, Kumar B, Rouf A, Shah BA, Taneja SC. Vasicine as tridentate ligand for enantioselective addition of diethylzinc to aldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:2639–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar KS, Ganguly S, Veerasamy R, Clercq ED. Synthesis, antiviral activity and cytotoxicity evaluation of Schiff bases of some 2-phenyl quinazoline-4(3)H-ones. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:5474–5479. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng J, Lin T, Wang W, Xin Z, Zhu T, Gu Q, Li D. Antiviral alkaloids produced by the mangrove-derived fungus Cladosporium sp. PJX-41. J Nat Prod. 2013;76:1133–1140. doi: 10.1021/np400200k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sokolova A, Yarovaya O, Semenova M, Shtro A, Orshanskay Y, Zarubaev V, Salakhutdinov N. Synthesis and in vitro study of novel borneol derivatives as potent inhibitors of the influenza A virus. Med Chem Commun. 2017;8:960–963. doi: 10.1039/C6MD00657D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Artyushin O, Sharova E, Vinogradova N, Genkina G, Moiseeva A, Klemenkova Z, Orshanskaya I, Shtro A, Kadyrova R, Zarubaev V, Yarovaya O, Salakhutdinov N, Brel V. Synthesis of camphecene derivatives using click chemistry methodology and study of their antiviral activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27:2181–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.