Abstract

Background

Annona muricata (Annonaceae) known as soursop is a common tropical plant species known for its numerous medicinal properties including obesity. The underlying mechanism of anti-obesity effect of A. muricata was investigated. The fat mass and obesity associated protein (FTO) is a validated potential target for anti-obesity drugs.

Methods

The interaction of compounds previously characterized from A. muricata was investigated against FTO using Autodock Vina. Also, modulation of FTO and STAT-3 mRNA expression by A. muricata was investigated in high fat diet induced obese rats (HFDR) using RT-PCR.

Results

A significant up-regulation of FTO gene was observed in HFDR when compared to control rats, while administration of A. muricata (200 mg/kg) significantly (p < 0.05) down-regulated FTO gene expression when compared to HFDR group. The effect of obesity on STAT-3 gene expression was also reversed by A. muricata (200 mg/kg). In silico study revealed annonaine and annonioside (−9.2 kcal/mol) exhibited the highest binding affinity with FTO, followed by anonaine and isolaureline (−8.6 kcal/mol). Arg-96 is a critical amino acid enhancing anonaine, isolaureline-FTO binding.

Conclusion

This study suggests the possible anti-obesity mechanism of A. muricata is via down-regulation of FTO with concomitant up-regulation of STAT-3 genes. This study confirmed the use of this plant in the management of obesity and the probable compounds responsible for its antiobesity effect are annonaine and annonioside.

Keywords: Annona muricata, Molecular docking, FTO and STAT-3 genes, Obesity

Introduction

Obesity refers to abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health. More than 1.5 billion adults above the 20 age mark are found to be overweight out of which 200 million men and about 300 million women obese. In the twenty-first century, excessive body mass and obesity are common health difficulties in contemporary society, predominantly in developed nations. Obesity is increasingly linked to several diseases and metabolic complications like cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer [1]. Environmental and genetic factors have been linked to predispose individuals to increase risk of obesity. Obesity, an impending global pandemic, is not being effectively controlled by current measures such as lifestyle modifications, bariatric surgery or available medications. Its toll on health and economy compels us to look for more effective measures [2]. Development of anti-obesity drugs has often been riddled with problems in the past. Some of the recently approved drugs for pharmacotherapy of obesity have been lorcaserin, phentermine/topiramate and naltrexone/ bupropion combinations. Although many anti-obesity drugs have been in use but due to several side effects newer and safer alternatives are highly sought after [3].

Advances in molecular technology have enhanced development of new drugs delineating new pathways in the pathophysiology of obesity and have led to the development of new drug targets like fat mass and obesity associated protein (FTO). FTO is currently a potential target for anti-obesity drugs [4] and one of the salient genes implicated in obesity [5]. It has also linked to obesity-related ailments, like cardiovascular diseases [1], hypertension [6], polycystic ovary syndrome [7], and type II diabetes [8]. The Signal transducer and activator transcription gene (STAT-3) function saliently in energy metabolism and is highly expressed in manifold metabolic tissues. It is an associate of the STAT protein family, which upon phosphorylation in response to growth factors and different cytokines is translocated to the nucleus of the cell in other to function as a transcription factors [9]. Phosphorylated STAT3 induces expression of SOCS3, which acts as a feedback inhibitor of the leptin signaling pathway [10, 11] and targeted deletion of STAT3 from neural tissue of mice, results in obesity [12].

Increase in the consumption of plants have been proven effective in weight and obesity management [13]. Annona muricata is a member of the Annonaceae family and it is a fruit-bearing tree with a lengthy antiquity of folkloric use. A. muricata, also well-known as soursop, graviola and guanabana, is a perennial plant which is mostly found in tropical and subtropical sections of the world [14]. The fruits of A. muricata are expansively used to make syrups, candies, beverages, ice creams as well as shakes. An extensive array of ethnomedicinal activities is underwritten of different parts of A. muricata, and home-grown societies in Africa and South America lengthily use this plant in their folk medicine [15, 16]. Abundant studies have substantiated these therapeutic activities comprising anticancer, anticonvulsant, anti-arthritic, antiparasitic [14, 16], antimalarial, hepatoprotective and antidiabetic activities [17, 18]. Extensive phytochemical assessments on various parts of A. muricata plant have revealed the presence of different phytoconstituents, which include alkaloids, phenolics, megastigmanes, flavonol triglycosides, cyclopeptides and essential oils amist others [14, 19].

The anti-obesity potential of this plant have been well documented [20, 21] but there is dearth of information on the likely mechanism of anti-obesity action. Hence, this study aims at investigating the involvement of fat mass and obesity gene (FTO) and STAT-3 in the anti-obesity action of Annona muricata Annonaceae using both in silico and in vivo approach.

Materials and methods

In silico experiment

Ligand preparation and docking scoring

Compounds previously characterized from A. muricata were retrieved from literatures and drawn using ChemAxon suite (https://www.chemaxon.com). The structures were optimized for docking using Open Babel (http://openbabel. org). The compounds were docked into the active sites of FTO (PDB = 3lfm) using Autodock Vina. The procedure was carried out by considering the flexibility of the ligand such that all rotational bonds were set free and the estimated binding energies for the best pose were recorded.

Plant materials

The leaves of A. muricata were collected from the horticulture garden of The Federal University of Technology Akure, Ondo State. The leaves were air dried, pulverized and stored at room temperature in air tight polythene bag prior to use. Five grams each of the leaves of A. muricata fruit were weighed into the extraction bottle and two hundred milliliters of distilled water was added to the bottle and left for 24 h to allow for extraction. Thereafter, the solution was filtered using a Whatman filter paper. The extract was stored air tight in a refrigerator until required for use.

In vivo study

Male Wistar rats (18 rats), 6 weeks old, weighting 125–170 g, were selected and divided into 3 groups (n = 6). They were allowed to acclimatize to experimental condition for two weeks. They were housed in clean cages and maintained under standard laboratory conditions (temperature 25 ` 2 C with dark/light cycle 12/12 h). Control group was 100% fed normal diet, and the other two groups were fed with with high fat diet with feed formulation (Table 1) as previously described [22]. Group I: normal rats and group II: negative control (obese untreated rats) were administered with 0.5 ml distilled water, group III: were obese rats administered with 200 mg/kg A. muricata aqueous extract for 21 days. The principles of Laboratory Animal care (NIH Publication 85–93, revised 1985) [23] were followed throughout the duration of the experiment.

Table 1.

Diet composition for normal control and high fat diet fed rats

| Normal control diet (g/kg) | High fat diet (g/kg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Skimmed milk | 500 | 500 |

| Lard | – | 300 |

| Rice bran | 200 | 90 |

| Corn starch | 160 | 70 |

| Premix | 40 | 40 |

| Groundnut oil | 100 | – |

Skimmed milk contains 360 g kg−1 protein; mineral and vitamin premix (10 g kg−1) contains 3200 i.u. vitamin A, 600 i.u vitamin D3, 2.8 mg vitamin E, 0.6 mg vitamin K3, 0.8 mg vitamin B1, 1 mg vitamin B2, 6 mg niacin, 2.2 mg pantothenic acid, 0.8 mg vitamin B6, 0.004 mg vitamin B12, 0.2 mg folic acid, 0.1 mg biotin H2, 70 mg choline chloride, 0.08 mg cobalt, 1.2 mg copper, 0.4 mg iodine, 8.4 mg iron, 16 mg manganese, 0.08 mg selenium, 12.4 mg zinc, 0.5 mg antioxidant and lard contains 99% fat

Gene expression

Total RNA was isolated from the rat pancreas with TRIzol Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) and DNA contaminant was removed following DNAse I treatment. The RNA was quantified and the purity confirmed spectrophometrically (A and E Lab UK) at 260 nm and 280 nm. The RNA was converted to cDNA using ProtoScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (NEB). PCR amplification was done using OneTaq® 2X Master Mix (NEB) using the following primer set (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primer sets for the gene expression

| Gene | Forward primers | Reverse primers | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| FTO | 5′-CTCTACCAGCACAGCAGAAA-3′ | 5-′ CAAAGGGCAGAGGCATAGAA-3′ | BC168239.1 |

| STAT-3 | 5-′ -. CACCCATAGTGAGCCCTTGGA-3′ | 5′ - TGAGTGCAGTGACCAGGACAGA-3′ | NM_012747.2 |

| GAPDH | 5′- AGACAGCCGCATCTTCTTGT – 3 | 5′ - CTTGCCGTGGGTAGAGTCAT −3′ | X02231.1 |

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The assay was performed using an optimization Template (cDNA) 5 μl, nucleas-free water 3.5 μl, forward primers 2 μl and reverse primers 2 μl and master mix 2 μl (Table 1), Reverse Transcription–PCR reaction was performed in a 15.0 μl final volume. Amplification conditions were: 94 °C pre-denaturation for 5 min, 94 °C for 30 s, annealing 55 °C for 30 s and Extension 72 °C for 30 s and then 5 min at 72 °C by 30 cycles.

Gel electrophoresis

Assessment of Polymerase Chain Reaction products (amplicons) were electrophoresed in 0.2% of agarose gel using 0.5 × TBE buffer (2.6 g of Tris base, 5 g of Tris boric acid and 2 ml of 0.5 M EDTA and adjusted to pH 8.3 with the sodium hydroxide pellet) with 3 μl EZ-vision (VWR Life Science). The expression product was visualized as bands by Blue-light-transilluminator. The intensities of the bands from agarose gel electrophoresiswere was quantified densitometrically using ImageJ software. Representative snapshot of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction-agarose gel electrophoresis data was plotted as a bar graph.

Statistical analysis

Data collected were analyzed using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS version 20 and were expressed as mean ± SEM. Duncan’s multiple ranges was used to separate the means. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when (p < 0.05). Graphpad prism version 7.04 was used to plot the graph. The intensities of the bands form agarose gel electrophoresis were quantified densitometrically using ImageJ software. Pymol was used to visualize the protein interaction while Ligplot was used to analyse the protein-ligand binding interaction.

Results

Identification FTO as A. muricata-derived compounds target

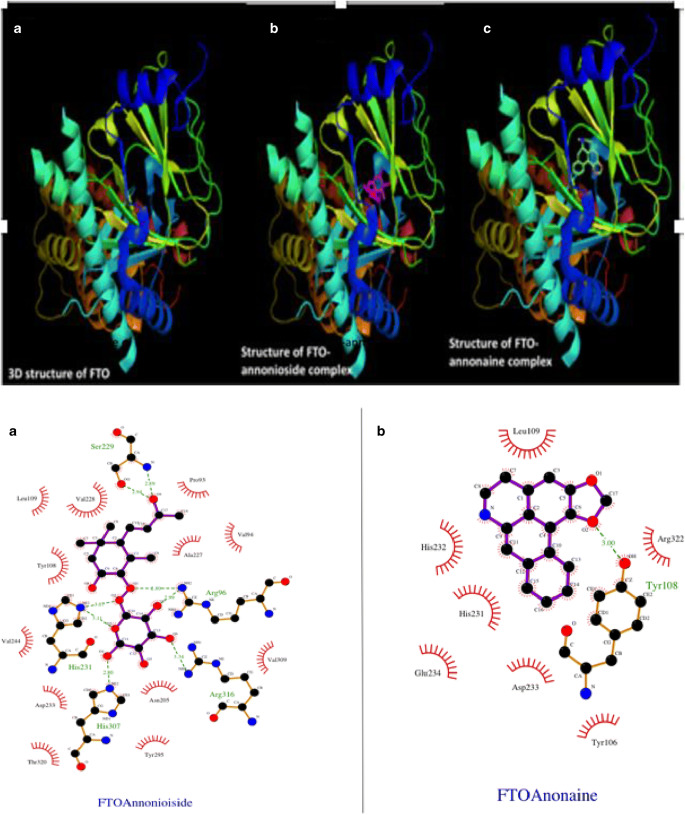

A library of phytocompounds from A. muricata based on previous studies of isolation and structural elucidation was created and maintained in our laboratory. Molecular docking analysis showed that A. muricata-derived compounds showed good affinity (Table 3) for FTO (−5.6 to −9.2 kcal/mol). Annonaine and annonioside showed the lowest binding energy for FTO both with binding energy of −9.2 kcal/mol, while epiloliolide showed highest binding energy (−5.6 kcal/mol) for FTO. Those with binding affinity ranging from −8.0 to −9.2 kcal/mol are presented in Table 4. The number of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions together with amino acid residues critical to ligand binding are also shown (Table 4). The binding pose (Fig. 1) of any compound at the binding site of any protein determines the amino acid residues it will interact with as well as binding affinity. The binding pose of annonioside and annonaine (phyto-compounds in A. muricata) with lowest binding affinity with FTO is shown in Fig. 1 Arg-96 is a critical amino acid residue critical to both annonioside and annonaine binding to FTO.

Table 3.

Binding affinity of A. muricata phytochemicals with fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO)

| 1 | Phytochemicals | Binding Energy (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Acetogenin | - 7.9 |

| 3 | Annohexocin | −6.3 |

| 4 | Annoionol A | −5.7 |

| 5 | Annoionol B | −6.7 |

| 6 | Annoionol C | −6.3 |

| 7 | Annomuricin A | −6.9 |

| 8 | Annnomuricin B | −6.7 |

| 9 | Annomuricin E | −7.1 |

| 10 | Annomutaicin | −7.0 |

| 11 | Annonacin | −7.3 |

| 12 | Annonacini one | −6.9 |

| 13 | Annonacin A | −7.2 |

| 14 | Annonaine | −9.2 |

| 15 | Annonioside | −9.2 |

| 16 | Annopentocin A | −6.4 |

| 17 | Annopentocin B | −7.3 |

| 18 | Annoreticuin 9one | −7.0 |

| 19 | Anomricine | −6.8 |

| 20 | Anomurine | −6.9 |

| 21 | Anonacin | −6.9 |

| 22 | Anonaine | −8.6 |

| 23 | arianaCIN | −6.7 |

| 24 | Asimicin | −6.9 |

| 25 | Asimilobine | −7.2 |

| 26 | atherspeminine | −7.8 |

| 27 | blumenol C | −5.9 |

| 28 | Bullaticin | −7.6 |

| 29 | CIS – annonaci10one | −7.1 |

| 30 | CIS – annoreticuin | −7.0 |

| 31 | CIS – goniothalamicin | −7.1 |

| 32 | CIS – panatellin | −6.3 |

| 33 | CIS – reticulacacin10one | −6.4 |

| 34 | CIS – solamin | −6.2 |

| 35 | CIS – uvariamic iv | −6.5 |

| 36 | CIS – uvariamicin .1 | −6.4 |

| 37 | Citroride A | −8.0 |

| 38 | Coclaurine | −6.9 |

| 39 | Cohibin A | −6.1 |

| 40 | Cohibin B | −5.7 |

| 41 | Corexamine | −8.1 |

| 42 | Corposolin | −6.3 |

| 43 | Corrosolone | −6.4 |

| 44 | Cs – reticulatacin | −6.7 |

| 45 | Epiloliolide | −5.6 |

| 46 | Epomuricerin B | −7.2 |

| 47 | Epomuricerin A | −6.5 |

| 48 | Epoxymurin A | −6.7 |

| 49 | Epoxymurin B | −5.6 |

| 50 | gigantetrocin A | −6.4 |

| 51 | gigantetronenin | −7.5 |

| 52 | Isoannonacin | −7.4 |

| 53 | Isolaureline | −8.6 |

| 54 | Javoricin | −6.6 |

| 55 | Kaemferol 3 –o-rutinoside | −8.1 |

| 56 | Monteeristin | −6.4 |

| 57 | Muricapentocin | −7.4 |

| 58 | Muricatacin | −5.9 |

| 59 | Muricatetrocin A | −6.9 |

| 60 | Muricatocin A | −6.8 |

| 61 | Muricatocin B | −7.0 |

| 62 | Muricoreacin | −6.7 |

| 63 | Murihexocin A | −6.5 |

| 64 | Murihexocin B | −6.4 |

| 65 | Normuciferine | −8.0 |

| 66 | Reticuline | −7.3 |

| 67 | Roseoside | −7.6 |

| 68 | Rutin | −8.5 |

| 69 | Sabadelin | −6.3 |

| 70 | Stepharine | −7.1 |

| 71 | Trilobacin | −7.4 |

| 72 | Xylopine | −8.4 |

Table 4.

Lead compounds from A. muricata and amino acid within the active site of FTO with hydrogen bond and hydrophobic interactions

| A. muricata compounds | Hydrogen bond | Hydrophobic interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Annonioside | 5 (Arg-96, Arg-316, His-307, His231, Ser-229) | 12 (Tyr-320, Tyr-295, Asn-205, Asp-233, Val-244, Val-309, Tyr-108, Leu-109, Val-228, Pro-93, Val-94, Ala-227) |

| 2 | Annonaine | 1 (Arg-96) | 8 (Tyr-108, Val-228, Arg-322, Asp-233, Leu-109, Glu-234, His-231, His-232 |

| 3 | Anonaine | 1 (Tyr-108) | 7 (Tyr-106, Asp-233, Glu-234, His-231, His-232, Leu-109, Arg-322) |

| 4 | Citroside A | 5 (His-232, Glu-234, Arg-96, Tyr-106, Arg-322) | 11 (Ala-227, Val-228, Val-94, Thr-92, Ser-229, Ile-85, Leu-109, His-231, Tyr-108, Leu-203, Asp-233) |

| 5 | Corexamine | 2 (Ala-227, Arg-96) | 9 (Pro-93, Val-228, Leu-109, His-231, Tyr-108, Tyr-106, Glu-234, Asp-233, Ser-229) |

| 6 | Isolaureline | Arg-96 | 9 (Val-228, Tyr-108, His-231, Ile-85, Leu-109, Pro-93, Ser-229, Val-94 |

| 7 | Normuciferine | Nil | His-232, Glu-234, Asp-233, Tyr-106, His-231, Tyr-108, Arg-96, Pro-93, Val-94, Val-228, Leu-109 |

| 8 | Rutin | 7 (Tyr-295, Asp-233, Asn-205, Ser-318, His-231, Trp-230, Ser-229) | 13 (Leu-109, Ile-85, Tyr-108, Pro-93, Ala-227, Val-228, Val-94, Arg-96, Val-309, Arg-316, Thr-320, Val-224, His-307) |

Fig. 1.

a 3D structure of FTO (A), FTO-annonioside complex (B) and FTO-annonaine complex (C). b. 2D illustration of FTO-annonioside complex (A) and FTO-annonaine complex (B) revealing interacting amino acids enhancing ligand binding

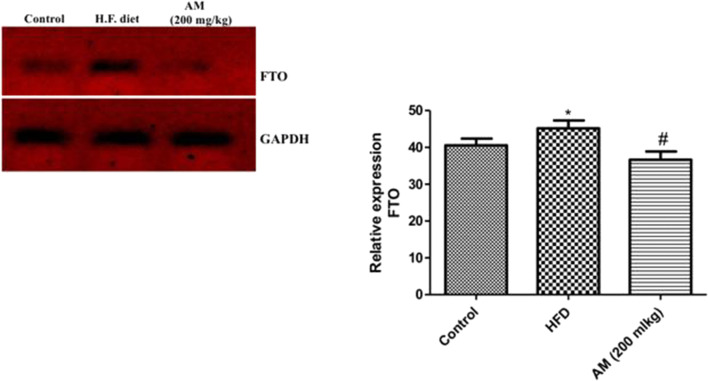

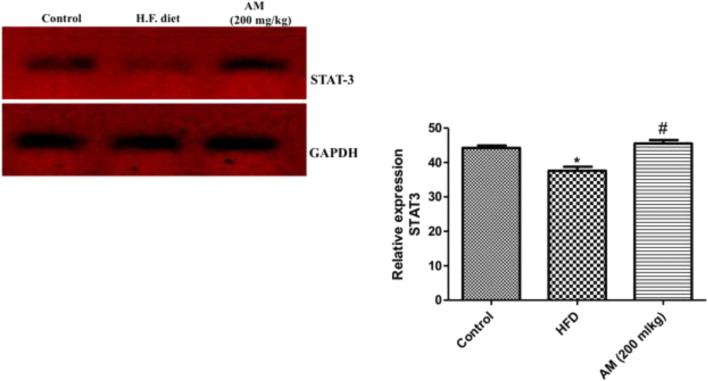

A. muricata administration modulates the expression of FTO and STAT-3 genes in HFD rats

In the present study, high fat diet up-regulated the expression (p < 0.05) of FTO gene relative to normal control rats while administration of A. muricata (200 mg/kg) significantly down-regulated (p < 0.05) FTO gene expression relative to high fat diet rats (Fig. 2). Conversely, induction of obesity in rats by HFD significantly down-regulated the expression of STAT-3 gene relative to normal control rats while treatment of obese rats with 200 mg/kg A. muricata significantly up-regulated the expression of STAT-3 gene relative to HFD group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Relative expression of fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) in high fat diet induced obese rat treated with A. muricata extract (200 mg/kg). * represent statistical difference (p < 0.05) relative to control while # represents statistical difference (p < 0.05) relative to HFD

Fig. 3.

Relative expression of Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 gene (STAT-3) in high fat diet induced obese rat treated with A. muricata extract (200 mg/kg). * represent statistical difference (p < 0.05) relative to control while # represents statistical difference (p < 0.05) relative to HFD

Discussion

Over the past century, phytochemicals in plants have been a crucial channel for pharmaceutical innovation and significant scientific interest in the biological properties of these substances [24]. Annona muricata is highly abundant in Nigeria and commonly used in the management of cancer, diabetes and obesity. Although the anti-obesity effect of this plant have been documented but the underlying mechanism is still very unclear. In the current study, we identified the molecular target of A. muricata-derived compounds as fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO). FTO is the first gene associated with body mass index (BMI) and risk for diabetes [25]. FTO is highly expressed in the brain and pancreas, and is involved in regulating dietary intake and energy expenditure [26]. High expression of FTO gene has been reported in obesity and down-regulation of FTO gene expression seems a logical approach to the management of obesity [27].

In this study, phytochemicals previously characterized from Annona muricata maintained at the Computational and Molecular Biology Unit, Department of Biochemistry, FUTA were docked into the crystal structure of human fat mass and obesity associated protein (FTO) using Autodock Vina. Annonaine and annonioside (−9.2 kcal/mol), anonaine and isolaureline (−8.6 kcal/mol), rutin (8.5 kcal/mol), xylopine and corexamine (−8.1 kcal/mol), normuciferine and citroside A (−8.0 kcal/mol) ranked best in binding affinity with FTO Table 3 out of 72 compounds documented for A. muricata (Table 3). The compounds interacted within the core of the protein (Fig. 1a) forming hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interaction with amino acids within the active site of FTO (Fig. 1b Table 4). The eight (8) lead compounds exhibited higher affinity for FTO than the standard drug; (1-[(2R,4S,5R) -4- hydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)oxolan-2-yl]-3,5-dimethyl-2,3- dihydropyrimidine-2,4-dione (−6.7 kcal/mol) co-crystallized with FTO. Arg-96 is a critical amino acid responsible for Annona muricata-derived compounds with FTO (Table 4).

In order to further investigate the anti-obesity effect of Annona muricata, an in vivo study was conducted to determine the effect of the plant extract on FTO gene expression in high fat diet induced obesity in rats. The expression of FTO gene was up-regulated in high fat diet induce obese rats (HFD) when compared to the control group (Fig. 2). This result was consistent with previously documented literature [5, 28–30]. Treatment of obese rats with Annona muricata (200 mg/kg) for 21 days showed significant down-regulation of FTO gene expression when compared to obese untreated rats. This was probably possible due to the vast enormity of phytochemicals in A. muricata extract especially the annonioside and annonaine that showed highest binding interaction with FTO from docking experiment relative to other phytochemicals found in A. muricata (Table 4) The down-regulation of FTO by phytocompounds in Annona muricata is an indication that they are inhibitors of FTO. The transformation of obese rats to normal after 21 days (data not shown) of treatment with A. muricata leave was as a result of reduced food intake as global overexpression of FTO has been known to cause obesity due to increased food intake [31].

The mRNA expression of STAT-3 gene was down-regulated in HFD rats when compared with the control group (Fig. 3). This result was in tandem with that which was reported by Ma et al. [32]. STAT3 has been implicated in the control of neuron/glial differentiation and leptin-mediated energy homeostasis and deletion of STAT-3 has been linked with insulin resistance and obesity [26]. Treatment of HFD rats with A. muricata extract (200 mg/kg) significantly (p < 0.05) up-regulated the expression of STAT-3 gene when compared with the HFDR group (Fig. 3), the leptin signaling pathway leading to reduction in food intake by the rats thereby reducing the weight of obese rats.

The results of the in vivo and in silico study suggests that A. muricata extract possess excellent anti-obesity property and its mechanism of action is probably through the down-regulation of FTO and up-regulation of STAT-3 genes leading to reduction in food intake. The molecular docking result provides a valuable starting point for subsequent design of new potential anti-obesity drugs. More studies (in-silico, in-vitro and in-vivo) on FTO genes in relation to adipogenesis is essential to further understand the role of this gene in obesity.

Conclusion

Based on the in silico analysis, we suggest all eight candidate compounds listed in Table 4 as potential FTO inhibitors that hinder the protein’s demethylation functions.

Compliance with ethical standards

Animal ethics

All of the animals received humane care according to the criteria outline in the Guide for the Care and the Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy Science and published by the National Institute of Health (USA). The ethic regulations have been followed in accordance with national and institutional guidelines for the protection of animals’ welfare during experiments. The experiment was carried out at the Bioinformatics and Molecular Biology Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chang PC, Wang JD, Lee MM, Chang SS, Tsai TY, Chang KW, Tsai FJ, Chen CYC. Lose weight with traditional Chinese medicine? Potential suppression of fat mass and obesity-associated protein. J Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2011;29(3):471–483. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2011.10507399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dina C, Meyre D, Gallina S, Durand E, Körner A, Jacobson P, Carlsson LM, Kiess W, Vatin V, Lecoeur C, Delplanque J. Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity. Nat Genet. 2007;39(6):724–726. doi: 10.1038/ng2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tung YL, Yeo GS, O’Rahilly S, Coll AP. Obesity and FTO: changing focus at a complex locus. Cell Metab. 2014;20(5):710–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Q, Xiao T, Guo J, Su Z. Complex relationships between obesity and fat mass and obesity locus. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13:615–629. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.17051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tews D, Fischer-Posovszky P, Wabitsch M. Regulation of FTO and FTM expression during human preadipocyte differentiation. Hormone and metabolic Res. 2011;43(01):17–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1265130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timpson NJ, Harbord R, Davey-Smith G, Zacho J, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard B. G.. does greater adiposity increase blood pressure and hypertension risk? Mendelian randomization using the FTO/MC4R genotype. Hypertension. 2009;54(1):84–90. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan Q, Hong J, Gu W, Zhang Y, Liu Q, Su Y, Zhang Y, Li X, Cui B, Ning G. Association of the common rs9939609 variant of FTO gene with polycystic ovary syndrome in Chinese women. Endocrine. 2009;36(3):377–382. doi: 10.1007/s12020-009-9257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vadakedath S, Kandi V, Pinnelli VBK, Godishala V. A review of signaling pathways and the genetics involved in the development of type 2 diabetes: investigating the possibility of a vaccine and therapeutic interventions to prevent diabetes. Am J of Clin Med Res. 2018;6(2):24–34. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benito C, Davis CM, Gomez-Sanchez JA, Turmaine M, Meijer D, Poli V, Mirsky R, Jessen KR. STAT3 controls the long-term survival and phenotype of repair Schwann cells during nerve regeneration. J Neurosci. 2017;37(16):4255–4269. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3481-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibars M, Ardid-Ruiz A, Suárez M, Muguerza B, Bladé C, Aragonès G. Proanthocyanidins potentiate hypothalamic leptin/STAT3 signalling and Pomc gene expression in rats with diet-induced obesity. Int J of Obesity. 2017;41(1):129. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Wu R, Chen HZ, Xiao Q, Wang WJ, He JP, Li XX, Yu XW, Li L, Wang P, Wan XC. Enhancement of hypothalamic STAT3 acetylation by nuclear receptor Nur77 dictates leptin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2015;64(6):2069–2081. doi: 10.2337/db14-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurzov EN, Stanley WJ, Pappas EG, Thomas HE, Gough DJ. The JAK/STAT pathway in obesity and diabetes. FEBS J. 2016;283:3002–3015. doi: 10.1111/febs.13709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandrasekarah CV, Vijayalaksmi MA, Prakash K, Bansal VS, Meenakshi J, Amit A. Herbal approach for obesity management. Am J Plant Sci. 2012;3:1003–1014. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2012.327119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gavamukulya Y, Abou-Elella F, Wamunyokoli F, AEl-Shemy H. Phytochemical screening, anti-oxidant activity and in vitro anticancer potential of ethanolic and water leaves extracts of Annona muricata (Graviola) Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7:S355–S363. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adewole S, Ojewole J. Protective effects of Annona muricata Linn. (Annonaceae) leaf aqueous extract on serum lipid profiles and oxidative stress in hepatocytes of streptozotocin-treated diabetic rats. Afr J Trad Compl Alternat Med. 2009;6:30–41. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v6i1.57071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul J, Gnanam R. M Jayadeepa R, Arul L. anti-cancer activity on Graviola, an exciting medicinal plant extract vs various cancer cell lines and a detailed computational study on its potent anti-cancerous leads. Current Topics in Med Chem. 2013;13(14):1666–1673. doi: 10.2174/15680266113139990117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishola IO, Awodele O, Olusayero AM, Ochieng CO. Mechanisms of analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of Annona muricata Linn. (Annonaceae) fruit extract in rodents. J Medicinal Food. 2014;17(12):1375–1382. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asare GA, Afriyie D, Ngala RA, Abutiate H, Doku D, Mahmood SA, Rahman H. Antiproliferative activity of aqueous leaf extract of Annona muricata L. on the prostate, BPH-1 cells, and some target genes. Integ Cancer Therapies. 2015;14(1):65–74. doi: 10.1177/1534735414550198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang C, Gundala SR, Mukkavilli R, Vangala S, Reid MD, Aneja R. Synergistic interactions among flavonoids and acetogenins in Graviola (Annona muricata) leaves confer protection against prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36(6):656–665. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasso S, Sampaio E, Souza PC, Santana LF, Cardoso CAL, Alves FM, et al. Use of an extract of Annona muricata Linn to prevent high-fat diet induced metabolic disorders in C57BL/6 mice. Nutrient. 2019;11. 10.3390/nu11071509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Coria-Tellez AV, Montalvo-Gonzalez E, Yahia EM, Obledo-Vazquez EN. Annona Musicata: a comprehensive review on its traditional medicinal uses, phytochemical, pharmacological activities, mechanisms of action and toxicity. Arab J Chem. 2018;11:662–691. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adefegha SA, Oboh G, Adefegha OM, Boligon AA, Athayde ML. Antihyperglycemic, hypolipidemic, hepatoprotective and antioxidative effects of dietary clove (Szyzgium aromaticum) bud powder in a high fat diet/streptozotocin-induced diabetes rat model. J Sci Food and Agric. 2014;94:2726–2737. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NIH Publication 85–93, revised 1985).

- 24.Moghadamtousi S, Goh B, Chan C, Shabab T, Kadir H. Biological activities and phytochemicals of Swietenia macrophylla king. Molecules. 2013;18(9):10465–10483. doi: 10.3390/molecules180910465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loos RJ, Yeo GS. The bigger picture of FTO—the first GWAS-identified obesity gene. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(1):51–61. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao Q, Wolfgang MJ, Neschen S, Morino K, Horvath TL, Shulman GI, et al. Disruption of neural signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 causes obesity, diabetes, infertility and thermal dysregulation. Proceedings of the national Academy of Sciences (USA). 10.1073/pnas.0303992101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Kalantari N, Doaei S, Keshavarz-Mohammadi N, Gholamalizadeh M, Pazan N. Review of studies on the fat mass and obesity-associated gene interactions with environmental factors affecting on obesity and its impact on lifestyle interventions. Area Atheroscler. 2016;12:281–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aik W, Demetriades M, Hamdan MK, Bagg EA, Yeoh KK, Lejeune C, Zhang Z, McDonough MA, Schofield CJ. Structural basis for inhibition of the fat mass and obesity associated protein (FTO) J Med Chem. 2013;56(9):3680–3688. doi: 10.1021/jm400193d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claussnitzer M, Dankel SN, Kim KH, Quon G, Meuleman W, Haugen C, Glunk V, Sousa IS, Beaudry JL, Puviindran V, Abdennur NA. FTO obesity variant circuitry and adipocyte browning in humans. New Eng J Med. 2015;373(10):895–907. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Padariya M, Kalathiya U. Structure-based design and evaluation of novel N-phenyl-1H-indol-2-amine derivatives for fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) protein inhibition. Computational Biol Chem. 2016;64:414–425. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess ME, Bruning JC. The fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene: obesity and beyond? Molecular Basis of Disease. 1842;2014:2039–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma Z, Wang G, Chen X, Ou Z, Zou F. Association of STAT3 common variations with obesity and hypertriglyceridemia: protective and contributive effects. Int J Molecular Sci. 2014;15(7):12258–12269. doi: 10.3390/ijms150712258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]