Abstract

Seasonal influenza vaccines lack efficacy against drifted or pandemic influenza strains. Developing improved vaccines that elicit broader immunity remains a public health priority. Immune responses to current vaccines focus on the haemagglutinin head domain, whereas next-generation vaccines target less variable virus structures, including the haemagglutinin stem. Strategies employed to improve vaccine efficacy involve using structure-based design and nanoparticle display to optimize the antigenicity and immunogenicity of target antigens; increasing the antigen dose; using novel adjuvants; stimulating cellular immunity; and targeting other viral proteins, including neuraminidase, matrix protein 2 or nucleoprotein. Improved understanding of influenza antigen structure and immunobiology is advancing novel vaccine candidates into human trials.

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Vaccines, Influenza virus

Current seasonal influenza vaccines lack efficacy against drifted or pandemic virus strains, and the development of novel vaccines that elicit broader immunity represents a public health priority. Here, Nabel and colleagues discuss approaches to improve vaccine efficacy which harness new insights from influenza antigen structure and human immunity, highlighting major targets, vaccines in development and ongoing challenges.

Introduction

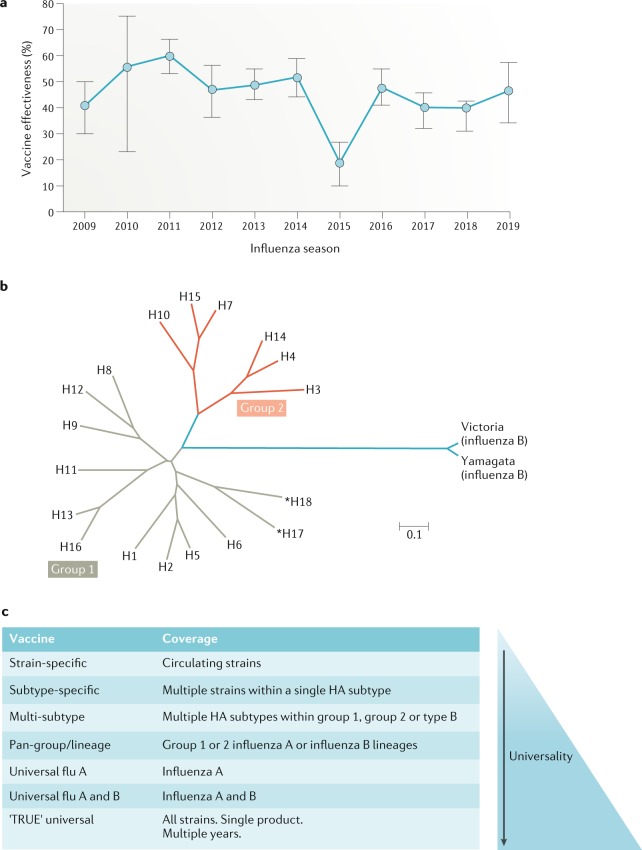

Vaccination represents an efficient and cost-effective way to contain influenza epidemics and preserve public health. Since their introduction in the 1940s, seasonal influenza vaccines have saved countless lives and limited pandemic spread. Influenza viruses nonetheless continue to evolve through genetic mutation and escape from natural immunity, and vaccines must be updated yearly. The protective efficacy of the current licensed vaccines varies each year (Fig. 1a), depending on the antigenic match between circulating viruses and vaccine strains. The immune status of the host can also affect vaccine efficacy. For example, young and elderly individuals are more susceptible to the complications of influenza infection1–3.

Fig. 1. A spectrum of efficacy for influenza vaccines.

a | Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccines from 2009 to 2019 (Data from ‘CDC: Past Seasons Vaccine Effectiveness Estimates’). The vaccine effectiveness is estimated from the US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network and measures the flu vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing outpatient medical visits due to laboratory-confirmed influenza. Adjusted overall vaccine effectiveness (%) and 95% confidence interval are shown. b | Phylogenetic tree of influenza A and influenza B haemagglutinin (HA). Eighteen influenza A HA subtypes have been detected in nature, and they can be further divided into group 1 and group 2 based on amino acid sequence composition, whereas influenza B HA subtypes have differentiated into two serologically distinct lineages (B/Victoria/2/87-like and B/Yamagata/16/88-like). Current licensed flu vaccines consist of one H1 strain, one H3 strain and one or two influenza B viruses. H2 virus also has the ability to infect humans and caused the pandemic in 1957. Occasionally, transmission of zoonotic influenza viruses, such as H5, H7 and H9, to humans has been reported. *H17 and H18 are from bat influenza. The scale bar indicates the numbers of amino acid substitutions per site. c | Incremental steps towards a ‘true’ universal influenza vaccine. Vaccine breadth against divergence of influenza strains, ranging from strain-specific (effective against a single, matched strain) to subtype-specific (effective against all or most strains within a given subtype), multi-subtype (effective against select subtype viruses), pan-group/lineage (effective against most subtype viruses within a group/lineage), type A (against all type A viruses), types A and B (against all type A and B viruses) and universal coverage (against most seasonal, drifted and pandemic strains for multiple years in a single product). Part c adapted from Erbelding et al.4.

New influenza viruses have precipitated pandemics several times over the past 100 years, specifically in 1918, 1957, 1968 and 2009 (ref.4). The threat of the re-emergence of old pandemic viruses and the emergence of novel viruses with pandemic potential underscore the need for durable and broadly protective influenza vaccines. Advances in immunology and virology, together with information from structural biology and bioinformatics, are facilitating the development of novel vaccine approaches5–8. Of particular interest are human broadly neutralizing antibodies directed to conserved viral structures. These antibodies arise naturally and can also be elicited through immunization9–36.

Current licensed influenza vaccines contain either inactivated or live attenuated influenza viruses. Most inactivated vaccines consist of split viruses or subunit influenza antigens (Table 1). Split vaccines are produced by disrupting viral particles with chemicals or detergents and are widely used because of the ease of manufacture. Subunit vaccines contain viral haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins that are partially purified after chemical or detergent splitting37. The live-attenuated influenza vaccines are made from cold-adapted viruses that do not replicate well at body temperature and are administered intranasally. This type of vaccine induces strong local mucosal immunity but is only recommended for non-pregnant individuals between 2 and 49 years of age37. The HA content in the licensed vaccines must be determined and standardized, but the quantity and quality of NA can vary by vaccine and by manufacturing processes. The trivalent vaccine has viral components from two influenza A strains and one influenza B strain, whereas the quadrivalent vaccine formulations add an additional influenza B virus. The viruses chosen for the vaccines are typically grown in chicken eggs; therefore the production heavily relies on a steady egg supply. Any modifications to viral protein must not impair influenza replication, which limits the repertoire of modified proteins that can be incorporated into a vaccine. Newer technology that utilizes cell culture for growing viruses has been developed, but the selected vaccine strains still need to be adapted for growth on cells, and the manufacturing cost remains high. More recently, a recombinant HA-based subunit vaccine produced from insect cells showed efficacy in healthy adults and improved protection in older subjects38.

Table 1.

Current licensed vaccines in the United States and Europe

| Region | Vaccine technology/platform | Vaccine type | Vaccine name (manufacturer) | Target/MOA | Adjuvant used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Inactivated virus | Split virus | Afluria (Seqirus) | HAI | None |

| Fluarix (GSK) | HAI | None | |||

| FluLavel (GSK) | HAI | None | |||

| Fluzone, Fluzone HD (Sanofi Pasteur) | HAI | None | |||

| Fluad (Seqirus) | HAI | None | |||

| Subunit | Fluvirin (CLS Limited) | HAI | None | ||

| Flucelvax (Novartis) | HAI | None | |||

| Live-attenuated | Live, cold-adapted | FluMist (AstraZeneca) | HAI | None | |

| Recombinant protein | Non-purified HA | FluBlok (Sanofi Pasteur) | HAI | None | |

| Europe | Inactivated virus | Split virus | Influvac, Imuvac (Abbot) | HAI | None |

| Fluarix, Alpharix, Influsplit (GSK) | HAI | None | |||

| 3Fluart (Omninvest) | HAI | Alum | |||

| Afluria, Enzira (Pfizer/CSL) | HAI | None | |||

| Vaxigrip, Vaxigrip Tetra (Sanofi Pasteur) | HAI | None | |||

| Subunit | Agrippal (Seqirus) | HAI | None | ||

| Fluad (Seqirus) | HAI | MF59 | |||

| Live-attenuated | Live, cold-adapted | Fluenz Tetra (AstraZeneca) | HAI | None |

HA, haemagglutinin; HAI, haemagglutination inhibition; HD, high-dose; MOA; mode of action. Sources: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: seasonal influenza vaccines, CDC: United States influenza vaccines 2019–2020.

Innovative approaches to vaccine design have been explored to develop a ‘universal’ influenza vaccine. The goal is to induce cross-protective immunity against diverse influenza viruses and prolong the duration of the immune responses. Among the universal influenza vaccine platforms are innovative technologies that utilize nucleic acid-based delivery, alternate viral vectors, recombinant proteins and virus-like particles39 (Table 2). In addition to the conserved epitopes on HA, other viral structures, such as NA and the extracellular domain of matrix protein 2 (M2), are also being considered40. Internal viral proteins, such as nucleoprotein (NP) and matrix protein 1 (M1), have also been targeted for the induction of cross-reactive T cell responses40.

Table 2.

Vaccine platforms in clinical development

| Vaccine technology/platform | Vaccine type | Sponsor | Target/MOA | Development stage | Clinical trial ID | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic acid | DNA | Vaccine Research Center, NIAID, NIH | HA NAbs | Phase I | 60,218–224 | |

| mRNA | Moderna | HA NAbs | Phase I | NCT03345043 | 225,226 | |

| Vector | Alphavirus–HA | Alphavax | HA NAbs | Phase I, II | 75 | |

| Adenovirus–HA | NIAID, NIH; PaxVax; VaxArt; Vaxin/Altimmune | HA NAbs | Phase I, II |

NHRC31230a; NHRC1999.0002a; |

77,227–230 | |

| Chimpanzee adenovirus–NP + M2 | Jenner Institute | T cells | Phase I | 74,231 | ||

| Modified vaccinia virus Ankara–HA; NP + M1 | Erasmus Medical Center; Jenner Institute; Vaccitech | HA NAbs; T cells | Phase I, II |

NTR3401b; |

66,76,165,231–234 | |

| Recombinant protein; VLP | Ferritin-based nanoparticle–HA; HA stem | Vaccine Research Center, NIAID, NIH | HA NAbs | Phase I | NCT03186781 | 88,118 |

| VLP–HA; NA; M1; M2 | Novavax | HA NAbs; T cells | Phase I, II | NCT01897701 | 82 | |

| Peptide–HA, NP, M1 | BiondVax |

T cells; B cells |

Phase II (USA); Phase III (EU) | 61,83,84 | ||

| Peptide–NP; M1; M2 | SEEK | T cells | Phase IIb | NCT02962908 | 85 | |

| Live virus | M2-deficient single replication virus | FluGen | B cells | Phase II | NCT03999554 | 86,87 |

HA, haemagglutinin; NIH, National Institutes of Health; M1, matrix protein 1; M2, matrix protein 2; MOA, mode of action; NA, neuraminidase; NAb, neutralizing antibody; NIAID, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease; NP, nucleoprotein; VLP, virus-like particle; aUS Department of Defense Protocol. bDutch Trial Register.

In this Review, we summarize the major advances in the field of influenza vaccines that are guiding the development of next-generation influenza vaccines. The major targets of current seasonal vaccines as well as vaccines in the development pipeline are reviewed, with a focus on improvements harnessing new insights from influenza antigen structure and human immunity. We highlight some of the unique challenges facing the influenza vaccine research field, many of which have contributed to the maintenance of established technologies, production systems and methods developed decades ago and which will require collaboration among the wide range of stakeholders, from funding sources to basic scientists, regulators and vaccine manufacturers.

Expanding the breadth of current vaccines

Influenza A viruses can be antigenically divided based on two key viral surface glycoproteins, HA and NA, whereas influenza B viruses form a single antigenic group with two distinct lineages, the B/Victoria/2/87-like and B/Yamagata/16/88-like lineages (Fig. 1b). There are 18 different HA subtypes that can be classified into two major phylogenetic groups based on genetic sequence41 (Fig. 1b).

Current licensed influenza vaccines contain three (trivalent inactivated vaccine) or four (quadrivalent inactivated vaccine) virus strains responsible for seasonal epidemics and need to be reformulated annually for the Northern and Southern Hemispheres based on global surveillance of drift in the circulating strains. Traditionally, the haemagglutination inhibition (HAI) antibody titre induced by the seasonal vaccines is used as an immune correlate of protection from influenza virus infection, but it tends to work only for homologous virus strains. The HAI titre correlates with in vitro neutralization of matched-strain influenza viruses42, and early work using this assay demonstrated a serum titre of 1:18–1:36 correlated with 50% protection from infection in humans43. Seasonal influenza vaccines are predominantly produced by propagation of influenza virus in chicken eggs, followed by inactivation, which is a time-consuming and labour-intensive process (see Table 1 for further details). Adaptation to growth in eggs has been noted to result in occasional mutations in HA that may impact the immune response44. This finding has been confirmed by a recent report comparing viruses grown in eggs versus in mammalian cells, which showed that mutations generated in the egg adaption process may hinder the generation of broadly neutralizing antibodies45. There are multiple efforts underway to improve upon these current vaccines while development of next-generation vaccines continues.

Antigen dose, regimen and optimization

Even though the development of a ‘true’ universal influenza vaccine remains a challenging goal, strategic plans have been proposed by field experts and government agencies4. Many steps have been taken towards improving current seasonal vaccines by expanding the breadth of protection within a subtype or across a group. They have shown progressive but incremental degrees of efficacy (Fig. 1c). For example, a high-dose, quadrivalent, inactivated vaccine is more effective than a standard dose vaccine at reducing the clinical outcomes associated with influenza infection46 and is now recommended for routine use in healthy elderly adults47, showing the benefits of a more highly effective, matched seasonal vaccine (Fig. 1c, strain-specific). An increase in protection against confirmed influenza-like illness has also been observed with a recombinant protein-based vaccine (FluBlok) and an adjuvanted vaccine (Fluad) in older adults38,48,49, likely through enhanced coverage of divergent subtypes beyond the matched vaccine strains (Fig. 1c, subtype-specific). In animal models, combinations of rationally selected H1 HA immunogens have been used to elicit broad and effective antibody responses, including one multivalent vaccine candidate that induced antibodies that neutralize diverse H1N1 viruses50, providing broader H1 or subtype-specific coverage (Fig. 1c, subtype-specific). Another approach to generate broader subtype-specific immune responses is to design ‘consensus’ sequences using computational algorithms51–56. One such antigen, termed ‘computationally optimized, broadly reactive antigen’ (COBRA), induces some cross-reactive antibodies within subtypes, such as H1, H3 or H5, in preclinical studies51,53,55. Another informatics approach involves computational analysis of influenza virus sequences and in silico design of synthetic HA antigens. Delivery of such ‘mosaic’ HA antigens in a modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) vector conferred protection against diverse influenza viruses57,58. These studies suggest that development of a supra-seasonal vaccine that could cover multiple strains within each circulating subtype, and thereby protect against drifted influenza virus strains, is feasible.

Coverage can be further expanded to include different subtypes within group 1 or group 2 HA (Fig. 1c, multi-subtype), especially the subtypes with pandemic potential, such as H2N2, H5N1 and H7N9. For example, vaccination with a DNA prime followed by seasonal influenza vaccine boost not only improved HA antibody responses but also induced protective immunity against divergent H1N1 and H5N1 in mouse and ferret challenge models59. This prime-boost immunization strategy has shown similar immunogenicity in clinical trials60, and together with a H2N2 vaccine can constitute the first generation of a ‘pan-group 1 HA’ pre-pandemic vaccine. Analogous prime/boost strategies can also be used to improve both B cell and T cell responses with other novel antigens, such as synthetic polypeptides61. New classes of immunogens that target the common viral structures among all HA antigens have also been designed and evaluated, and antibodies that react broadly with all HA antigens within group 1, group 2 or influenza B have been isolated9–36, further paving a pathway to a vaccine to cover most influenza A and influenza B strains (Fig. 1c, pan-group/lineage; universal flu A; universal flu A and B). A true universal vaccine, however, should protect against all influenza strains and should be durable for multiple years in a single product (Fig. 1c, “TRUE” universal).

Delivery and display

Advances in delivery methods, including live-attenuated vaccines, viral vectors, mRNA technology and nanotechnology, have shown promise in inducing more cross-reactive immunity. A prototypical recombinant influenza B virus vaccine that incorporated mutations in viral PB1 and PB2 genes resulted in a stable, attenuated virus that conferred protection against lethal heterologous influenza B virus challenge62. Replication-defective vectors, such as MVA, adenovirus, Newcastle disease virus and alphavirus, can express various influenza antigens and be used in a prime-boost regimen, where they have shown some degree of success in eliciting both homologous and heterologous immunity62–77 (Table 2). A nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine encoding HA from the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus formulated with lipid nanoparticles induced HA stem-directed antibodies in rabbits and mice and protected mice from a heterosubtypic virus challenge78. Virus-like particle influenza vaccines have also been evaluated in various clinical trials, and some have elicited long-lasting immunity and induced cross-reactive HAI responses against heterologous strains79–82. Recombinant protein-based vaccines consist of peptides from conserved viral structures61,83–85, and modified live influenza viruses86,87 are also being evaluated in late-stage clinical trials (Table 2). Influenza virus HA has also been rationally designed for presentation on a bacterial-based ferritin nanoparticle88. These particles allow HA to retain its native trimeric conformation while displayed in an ordered array, to increase valency that may facilitate cross-linking of B cell receptors. In animal models, this nanoparticle vaccine improved HA antibody responses and conferred protection against heterologous virus challenge88, and it is currently being evaluated in a phase I clinical trial (Table 2).

Novel HA-based vaccines

Antibodies against HA are a major component of the human immune response to both natural influenza virus infection and influenza vaccination, and measurement of antibody responses against HA by the HAI assay is the recognized correlate of protection from influenza virus infection. As a result, HA is a target for both current seasonal vaccines and many candidates in development for universal influenza vaccines. Seasonal vaccine manufacturers characterize their vaccine products, in part, by measuring and standardizing the quantity of each HA component of their vaccines. Recent advances in structural biology, including crystallography, electron microscopy and bioinformatics, have enabled a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the structure of HA, which has subsequently provided opportunity for vaccinologists to employ structure-guided vaccine design.

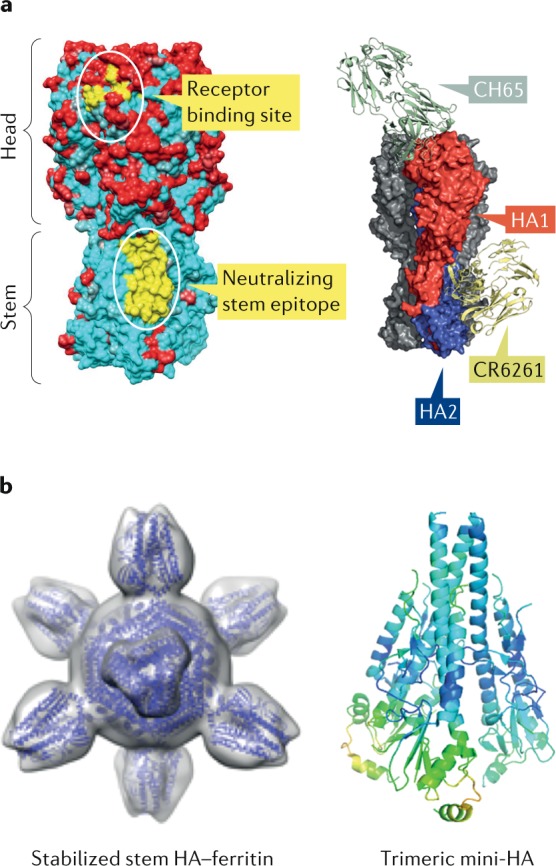

HA is a type I membrane glycoprotein that forms a homotrimer that is typically glycosylated at between five and seven sites per monomer (Fig. 2a, left) and is the major target of neutralizing antibodies89–91. HA mediates viral entry by binding to its receptor, terminal sialic acids on glycoproteins or glycolipids of host respiratory epithelial cells, and mediates fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell in the endosome92. The molecular structures of HA from different subtypes have been determined. The overall architecture of HA from different strains is conserved, although the surface sequence composition and glycosylation patterns differ among influenza virus subtypes and types, especially in regions near or at the receptor binding site (RBS) localized in the globular head92. The RBS itself is a shallow pocket surrounded by three secondary elements, the 130-loop, 190-helix and 220-loop, with a base consisting of four highly conserved amino acid residues. In both H1 and H3 viruses, the number of N-linked glycosylation sites on the HA head increased after they entered the human population, and these modifications can contribute to ‘antigenic drift’ of the virus93,94. One example is the evolution of a pandemic H1N1 strain into a seasonal strain, during which it acquired two additional glycans near the RBS which effectively masked the respective antigenic regions from recognition by antibodies. Humoral responses to HA have been associated with protective immunity95. Antibodies directed to the head region of HA can be routinely elicited by viral infection and seasonal vaccination10,11,13,14,16–18,20,96,97. These antibodies provide immunity by blocking viral entry to host cells or preventing receptor-mediated endocytosis. Memory B cells and long-lived plasma cells are often found following infection or immunization to provide durable protection against matched or closely-related viruses. However, these antibodies tend to be strain-specific and do not neutralize drifted variants mainly due to the high mutation rate of the HA globular head, especially in regions around the RBS.

Fig. 2. Structural basis for the induction of broadly neutralizing antibodies against HA.

a | Left: structure of influenza haemagglutinin (HA). The trimeric protein consists of a globular head that mediates attachment and a stem region that anchors the viral spike. Sequence variability among H1 HA subtypes is depicted in red (variable) and cyan (conserved). Conserved neutralizing antibody epitopes in the receptor binding site and stem are mapped onto the crystal structure of the HA ectodomain from A/South Carolina/1918 (H1N1) (PDB 1RUZ) and highlighted in yellow. Right: HA structural model showing a broadly neutralizing H1 subtype-specific (CH65) antibody bound to the receptor binding site and a pan-group 1 (CR6261) antibody targeting the stem (adapted from Nabel and Fauci5). CH65 is isolated from an adult donor and neutralizes various H1N1 viruses by preventing viral attachment to its sialic acid-containing receptor. CR6261 also comes from a human subject and neutralizes a broad range of viruses within group 1 HA. It recognizes a highly conserved helical region in the HA stem and blocks viral entry by preventing membrane fusion. b | Structural models of novel immunogens that target the conserved HA stem region: stabilized stem HA–ferritin and trimeric mini-HA. Stabilized stem HA–ferritin is generated by fusion of the stem region of HA to a self-assembling ferritin nanoparticle. This immunogen lacks the immunodominant head domain and elicits only stem-specific immune responses. The mini-HA is another ‘headless’ antigen that preserves the structural and antigenic integrity of the HA stem and has been shown to provide heterosubtypic immunity. Part a adapted from ref.5, Springer Nature Limited. Part b (left) reprinted from ref.118, Springer Nature Limited. Part b (right) adapted with permission from ref.119, AAAS.

Broadly neutralizing antibodies against the more conserved stem region of HA were identified as early as the 1990s (refs21–31,33–35). The C179 monoclonal antibody, isolated in mice, displayed unusually broad specificity and neutralized many group 1 HA viruses, including H1, H2, H5, H6 and H9 subtypes32,98. Unlike most HA antibodies that recognize the highly variable HA head region, C179 binds to a conserved stem region of the HA. A follow-up study has also shown that heterosubtypic protective immunity can be induced by vaccination with an immunogen lacking the head domain99, suggesting that an HA stem-only immunogen could induce antibodies with more breadth. Subsequently, this class of antibodies was isolated from humans, and structures of several have been extensively characterized21–31,33–35. Broadly neutralizing antibodies, such as CR6261 and F10, cross-react with most group 1 influenza A HA subtype viruses24,33. Crystal structures of CR6261 and F10 in complex with HA revealed that both antibodies bind to a hydrophobic pocket on the stem near the fusion peptide with a very hydrophobic complementary domain region (CDR) H2 and use a conserved tyrosine residue in CDR H3 to stabilize the interaction with HA24,33. They inhibit the virus by fixing HA in its prefusion form, thereby inhibiting membrane fusion24,25 (Fig. 2a, right). Other stem-directed antibodies may inhibit proteolytic cleavage of HA21,25, prevent viral replication by disrupting particle egress100 or inhibit NA enzymatic activity through steric hindrance101,102.

Many of these stem-directed human antibodies were derived from the VH1-69 germline, but antibodies that utilize different germline families, such as VH1-18, VH6-1 and VH3-23, and additional neutralizing epitopes on the stem have also been identified28,103. Most stem-directed antibodies neutralize influenza strains within group 1 or group 2, but a few have been shown to neutralize across both groups within influenza A and at least one, CR9114, protects mice from both influenza A and influenza B virus challenge, although it binds but does not neutralize influenza B in vitro21–31,33–35. The generation of these broadly neutralizing antibodies by different vaccination platforms or immunogens in various animal models and in clinical trials has been demonstrated59,60,88,104–107. Although these stem-directed antibodies are present in humans, most appear to be less prevalent in human sera and less potent neutralizers than those directed to the HA head region108,109. Several different approaches have been taken to overcome these challenges. Immunization of human subjects with pre-existing immunity to H1N1 and H3N2 viruses with pandemic vaccines that contain divergent head but conserved stem domains, such as H5N1 or H7N1, have been shown to induce stem-binding antibodies with limited neutralizing activity104,106. Priming with a novel pandemic H5N1 or H7N9 DNA vaccine followed by matched-strain monovalent inactivated virus vaccine boost has improved the breadth of immune response in animals and in clinical trials over monovalent inactivated virus vaccine alone59,60. Broadly neutralizing antibodies that neutralize both group 1 and group 2 influenza virus have indeed been isolated from vaccinees who received this regimen28,103. Another approach is sequential immunization with synthetic, chimeric HA in which the HA1 domain is derived from different, novel subtypes while the stem remains the same. Prime/boost immunization with chimeric HA generates cross-neutralizing antibodies and protects animals from heterologous viral challenge110–113. These chimeric HA vaccines have been evaluated in a phase I clinical trial, and the interim analysis suggested that stem binding antibodies that react with select group 1 HA subtypes (H1, H2, H9 and H18), measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, can be boosted in subjects with pre-existing anti-stem antibody titres, although neutralization was not evaluated114. Additionally, chimeric HA vaccines can also be constructed with exotic head domain sequences from avian species, allowing the potential for sequential immunization and repeated boosting of cross-reactive, stem-directed antibodies115–117. More recently, two groups independently designed and engineered a ‘headless’ HA construct in which only the NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal regions of HA1 and entire HA2 were presented118,119 (Fig. 2b). In one design, the HA stem was stabilized by a trimerization domain119, and in the other, the stem was fused and presented on a bacterial ferritin nanoparticle118,120. Both headless immunogens elicit heterosubtypic immunity and protect animals from a heterologous lethal H5N1 virus challenge. One is currently under evaluation in a phase I clinical trial121 (Table 2). Overall, these stem-based immunogens represent promising candidates for broadly protective vaccines and warrant further clinical investigation.

In addition to the conserved stem epitopes, there are also new developments on broadly neutralizing antibodies targeting the HA head, especially the RBS. An antibody that binds close to antigenic site B, C139/1, was first reported in 2009, and it neutralizes many influenza subtypes (H1, H2, H3, H5, H9 and H13)20. Many head-directed antibodies with varying degrees of specificity have subsequently been identified, and the majority of these antibodies tend to be subtype-specific10,11,13,14,16–18,20,96,97. They neutralize the virus by blocking viral attachment to the host cells and, in general, utilize the CDR loop to make minimum contact with the relatively small RBS. Antibodies directed against additional sites in the HA head located outside the RBS have recently been identified that do not mediate HAI but can mediate neutralization122–124. Antibodies to conserved epitopes on the interface of the HA head trimer recognize a broad spectrum of influenza viruses and confer hetero-subtypic protection in mice dependent on Fc activity125,126. The challenge for vaccine design will be to present the minimum, most conserved residues in this binding pocket in a functional conformation, while avoiding the highly variable surrounding regions.

Vaccines based on other viral proteins

In addition to harnessing and improving the humoral immune response to the HA antigen, universal influenza virus vaccines could potentially benefit from incorporating diverse and more highly-conserved antigens.

Neuraminidase

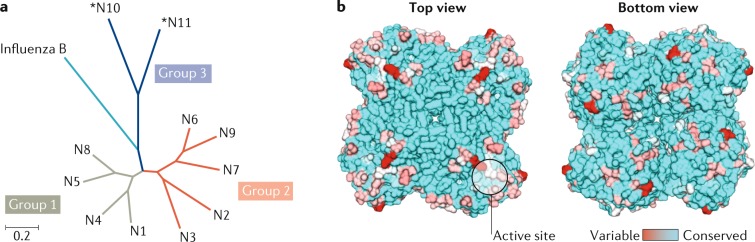

A recent study utilizing a human influenza challenge model suggested that serum neuraminidase inhibition activity may be more predictive of susceptibility to live virus challenge than the current standard predictor of protection, the HAI titre127–129. NA is a type II transmembrane glycoprotein composed of 11 subtypes that fall into three genetic groups (Fig. 3a). This tetrameric protein removes terminal sialic acids and facilitates the release of newly formed viral particles130 (Fig. 3b). Although antibodies to NA have been identified131–134, little is known about how they affect the outcome of influenza virus infection135. NA is a validated drug target as small-molecule inhibitors to NA, such as oseltamivir, zanamivir and laninamivir, can modulate disease severity136. Recent identification and characterization of broadly protective antibodies that recognize the active site of NA suggest that these antibodies could potentially be induced by vaccines137. Antigenic drift and shift of NA is thought to occur independently of HA. As a result, N2 antibodies may have helped limit the severity of the H3N2 pandemic of 1968, in which the HA changed but the NA did not138. Although the potential importance of NA as an influenza immunogen was recognized at the time of that pandemic139,140, current seasonal influenza vaccine manufacturers are not required to measure the quantity or quality of NA in marketed products. Simply adding a known quantity of conformationally correct NA to current seasonal vaccines may improve efficacy and, potentially, breadth against drifted strains of influenza141,142. Additional efforts, such as the creation of ‘consensus’ NA immunogens, are being tested in animal models and may hold promise for using NA as a component of a more universal vaccine143.

Fig. 3. Structural basis for the induction of neutralizing antibodies against NA.

a | Phylogenetic tree of influenza A and influenza B neuraminidase (NA) subtypes. Influenza A NA can be divided into three genetically distinct subgroups: group 1 consists of N1, N4, N5 and N8; group 2 consists of N2, N3, N6, N7 and N9; and group 3 has two NA subtypes from fruit bats (*N10 and *N11). The scale bar indicates the numbers of amino acid substitutions per site. b | Structure of influenza NA. Top and bottom views of NA tetramers are shown. Sequence conservation from select NAs from 1977 to 2018 depicted in red (variable) and cyan (conserved) and mapped onto the crystal structure of the NA ectodomain from A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) (PDB 3TI6).

Matrix protein 2 ectodomain

Influenza A virus matrix protein 2 ectodomain (M2e) has been proposed as a universal vaccine antigen144,145, but M2e presents multiple challenges. Although the M2 ion channel is essential for influenza virus budding and disassembly of the viral core, and, thus, is highly conserved, its surface-exposed amino terminal ectodomain is poorly immunogenic146. If M2e is conjugated to various carriers or delivered as a virus-like particle, its immunogenicity improves147. In fact, IgG-mediated protection from a broad range of influenza virus strains has been demonstrated in animal models148. However, this protection derives from Fc effector functions, and no robust immune correlate of protection has been established149, which makes quantifying M2e-based immunity challenging and limits the measurement of vaccine efficacy to large field trials. A passively transferred human monoclonal antibody to M2e did decrease the viral load in a human influenza challenge model150. The immune response of M2e can be improved with adjuvants, and, in a phase I clinical trial, an M2e–flagellin fusion protein vaccine induced strong antibody responses at high dose, although the systemic reactogenicity profile was unacceptable146. Given that M2e is a relatively small protein and viral escape mutants have been identified, it is more likely for an M2e-based vaccine to be used as an adjunct to HA-based vaccines to provide additional protective immunity, especially when there is a mismatch between the vaccine and circulating epidemic strains151.

Nucleoprotein

Stimulation of CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cell responses, including recruiting intraepithelial tissue resident memory cells of the lung152 or T follicular helper cells crucial to germinal centre formation in the lymph node153, may improve the durability, potency and breadth of influenza immunity. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses have been shown to be associated with heterosubtypic immunity against influenza154–158. T cells have been implicated, both directly through CD8-mediated cytotoxicity and indirectly via CD4 help, in a breadth of protection in murine159 and non-human primate160 models of influenza infection. Although T cell-based immunity varies depending upon HLA type, and no absolute correlate of protection has yet been established, studies in humans have associated higher numbers of cross-reactive T cells with protection from influenza infection161,162. NP is an internal protein conserved across influenza A strains that has been identified as a target of T cell immunity and studied in early phase clinical trials. An MVA-vectored NP + M1 vaccine induced CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, detected by interferon-γ (IFNγ) enzyme-linked immunospot, across younger and older aged cohorts (Table 2). This vaccine also enhanced T cell and strain-specific antibody responses when used together with seasonal vaccines163,164. In an influenza challenge, MVA NP + M1-vaccinated individuals had lower symptom scores than unvaccinated controls, although the number of individuals studied was small66,165. As in the above-mentioned studies, viral-vectored and nucleic acid-based vaccine platforms have been found to induce improved T cell responses over traditional inactivated influenza vaccines in animal models and in a human influenza virus challenge59,60,166, and such alternative platforms may be required for a universal vaccine to effectively recruit T cells.

Vaccine adjuvants

Another way to improve influenza vaccines is to include adjuvants in vaccine formulations. Adjuvants are immunostimulatory agents that enhance the immunogenicity of the co-administered antigens. They can potentially provide other advantages, such as dose sparing, polarization of immune responses towards a more desirable response, acceleration of vaccine-induced immune response and increased immunogenicity in populations with poor immune responses, such as the elderly and patients who are immunosuppressed. Several adjuvants have been approved for use in influenza vaccines, including Alum, MF59, AS03 and AF03 (refs167,168). The most widely used vaccine adjuvant, aluminium salt, showed little effect when used with H1N1 or H5N1 pandemic influenza vaccines169,170. MF59, a squalene oil-in-water emulsion approved for influenza vaccines since 1997, increases antibody responses with both seasonal and pandemic subunit vaccines and has been shown to enhance protective efficacy against hospitalization associated with influenza171. Similar to MF59, both AS03 and AF03 are oil-in-water adjuvants containing squalene with similar proposed modes of action172–174. Both AS03 and AF03 have been approved for pandemic influenza vaccines. In general, these adjuvants are safe and well tolerated, and improve both the potency and breadth of humoral immune responses. Other adjuvants have been tested in animal models and clinical trials, including saponins, Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, polysaccharides and glycolipids. Saponins are amphipathic glycosides commonly found in plants, and a newer generation of saponin-based adjuvant, Matrix-M, has advanced to a phase II trial and showed efficacy with an H7N9 virus-like particle vaccine175.

TLR agonists improve vaccine efficacy and antitumour immunity by promoting innate inflammatory responses and inducing adaptive immunity. This class of adjuvants covers a very broad spectrum of pathogen-derived compounds, including lipopeptides, glycolipids, nucleotides, small-molecule inhibitors and bacterial-derived components, such as flagellin176. TLR agonists, such as TLR4, TLR5, TLR7/8 and TLR9, have all been used with various influenza immunogens in animal studies and show varying degrees of increased efficacy in clinical trials177–186. One major concern about these TLR ligands is the variation in the relevant receptors and the downstream signalling pathways and biodistribution in different species, which necessitates use of proper animal models or in vitro surrogates to establish the safety profile.

For the deployment of adjuvants in the next generation of influenza vaccines, careful consideration of efficacy in humans, as well as ease and consistency of manufacturing, will require careful consideration. More importantly, the safety of new adjuvants and vaccine risk–benefit considerations will need to be assessed. A safe and effective adjuvant has the potential to provide improved potency and breadth that might increase vaccine efficacy in normal and immune compromised subjects. Such an adjuvant could be a vital tool to provide either superior immune enhancement and/or dose sparing and, thus, help the efficacy and deployment of a universal influenza vaccine.

Clinical and regulatory considerations

Current influenza vaccines

The clinical development of universal influenza vaccines faces challenges not common to programmes for other pathogens. Although current vaccines are considered insufficient to address the antigenic variation in seasonal influenza virus strains or the threat of pandemic strains, they have been in use for more than 70 years. A large enterprise and standardized practices have been established to support the $1.6 billion US market and estimated $4 billion global market187. The system involves semi-annual recommendations from the WHO (WHO: Influenza vaccine viruses and reagents), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and collaborating centres for strain selection to include in vaccine formulations for the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Vaccines are reformulated and manufactured annually in a process that involves millions of embryonic eggs, genetic reassortment, amplification of vaccine viruses, and worldwide distribution188. Numerous organizations devote substantial resources to surveillance, evaluation and recommendations on vaccine efficacy, safety and clinical use. Although this cumbersome and elaborate system is entrenched, it produces only a few hundred million doses for the world’s 7 billion inhabitants, and vaccine efficacy is at best 60% in years when the vaccine viruses are well matched to circulating strains189. Nevertheless, the system is familiar, consistent, cost-effective and well understood, so displacing current practices is a significant hurdle for the development of new and potentially improved vaccine technologies. The availability of licensed vaccines also makes a placebo-controlled trial difficult to justify in countries, such as the United States, that recommend the current seasonal vaccine for wide use.

Demonstrating clinical efficacy

A major obstacle facing the clinical development of universal influenza vaccines is a well-established immune correlate of protection for influenza. Licensure of new seasonal vaccines is granted with evidence of efficacy obtained from past clinical trials with influenza illness as the primary end point, and approvals of annual supplements for new virus strains do not require additional clinical data specific for the new strain for inactivated and recombinant protein vaccines190.

Evaluating the efficacy of novel influenza vaccines may require giving the experimental vaccine in addition to conventional seasonal vaccine and determining whether efficacy is improved when circulating strains are mismatched with the seasonal vaccine. To demonstrate efficacy, clinical trials will likely be large and complicated, with potential immune interactions between products. Therefore, understanding the basis of influenza immunity and development of additional laboratory measurements as surrogates for vaccine efficacy are needed. If an accepted surrogate end point can be induced by the candidate universal influenza vaccine — determined by large-scale efficacy studies — and the protection is comparable to or superior to that induced by conventional vaccines, field trials could be designed to compare the candidate with licensed vaccines head-to-head. If there is no surrogate for efficacy, advanced development becomes more difficult.

Vaccine-induced immune responses, such as HAI antibody titres, are often evaluated and used as a surrogate to extrapolate vaccine effectiveness, especially in vulnerable populations not included in the efficacy trials, and in the case of a pandemic, licensure is granted based on HAI titres with a commitment to assess efficacy during the pandemic190–192. HAI was originally developed in the 1950s as a surrogate for neutralization because the assay was rapid and easier to perform193. However, HAI depends on blocking access to the sialic acid binding pocket on the HA head. In most cases, antibodies with HAI activity are highly strain-specific. When trying to develop vaccine platforms that induce broad protective efficacy, having an immune correlate that favours strain-specific immunity can be detrimental, especially when trying to displace established products.

Most vaccine design approaches for achieving immunity against future drifted seasonal and pandemic strains purposely avoid the induction of antibodies to the sialic acid binding pocket, so the use of HAI as a surrogate end point for achieving accelerated licensure is not an option. Therefore, advancing universal influenza vaccines will likely require expensive field efficacy studies and, eventually, the development of other surrogate end points. For example, antigens targeting the HA stem, designed to elicit antibodies with broad cross-subtype recognition, will not induce HAI34. They will potentially induce neutralizing activity or Fc-mediated antibody functions that could be monitored194. Neutralizing activity is likely to be an acceptable surrogate for protection, as HAI was originally developed as a surrogate for neutralization, which is the mechanistic correlate being assessed by HAI. Other mechanisms of neutralization beyond blocking receptor binding have also been recognized195,196. Therefore, although HAI is sufficient for strain-specific protection because it reflects neutralization through blocking receptor interaction, HAI is not required for protection, and so induction of broad neutralizing activity could be a better surrogate marker of immunity against diverse influenza strains. Another reason to focus on neutralizing activity instead of HAI is the continuous change in genetics and antigenicity of influenza viruses. For example, as H3N2 viruses evolve glycosylation patterns on HA, receptor binding or NA agglutination of red blood cells often changes, making it difficult to characterize these viruses with standard reagents and assays197. Recent advances in HA probes for flow cytometry, single-cell analysis, sequencing technology and bioinformatics have led to the identification of antibody lineages associated with HA-stem-targeted broad neutralization of influenza strains across subtypes, and in some cases across groups. This type of analysis and application to vaccine-induced immune responses creates the possibility of using molecular sequencing of immunoglobulin genes from sorted B cells as clinical trial end points28,103,198,199. Although the association of antibody sequences and clinical outcomes from infectious diseases has not been established, these biomarkers represent a potential path forward200.

Other approaches to universal influenza vaccines include the ectodomain of the M2 protein that depends on Fc-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity201. Alternatively, vector-based and live-attenuated virus approaches may involve T cell-mediated protection in addition to neutralizing antibodies202,203. However, to date, there has not been an accepted surrogate end point for vaccine efficacy based on an in vitro cell-mediated cytolytic activity, so for vaccines that do not achieve a serological end point of HAI or neutralization, it is more likely that demonstration of clinical efficacy will be needed for regulatory approval.

Human influenza challenge has been studied extensively in the past, and there are new efforts to extend the capacity for these studies204,205. The original establishment of an HAI titre of 1:40 as a correlate of protection and a surrogate end point for vaccine protection was, in part, based on data from human challenge43. FDA-approved influenza challenge viruses are available, and studies have been completed to define safe challenge doses204 and to establish criteria for quantifying clinical illness206. As for HAI in the past, immune correlates using more modern reagents and assays can be assessed in experimentally infected humans207, and human challenge can also be used to test efficacy of vaccines and passively administered antibody. A major limitation of the human influenza challenge model is that the infection, by intent, is largely restricted to the upper airway. Prevention of lower airway disease is one major objective for vaccine development, so vaccine efficacy cannot be directly assessed for the clinical end point of primary interest. In addition, the numbers and diversity of influenza viruses available for human challenge study are limited so it will be difficult to show vaccine efficacy against multiple viruses. In general, higher doses of virus are used for challenge than are seen in natural infection. Nevertheless, if vaccines or passively administered monoclonal antibodies can prevent or diminish upper airway disease, or show an effect on viral load in the human challenge model, this may facilitate regulatory approval and may contribute to the identification of alternative immunological correlates of protection.

Post-licensure considerations

Many recently licensed influenza vaccines have been granted accelerated approval based on safety and induction of serum HAI, which is considered a surrogate marker of protection. However, accelerated approval comes with substantial post-marketing contingencies that add to the time and cost of influenza vaccine development. It is likely that novel influenza vaccines, even those with evidence to support licensure, will have post-marketing requirements. The FDA was specifically charged with establishing a post-market risk identification and analysis system by the FDA Amendments Act of 2007 (ref.208), in part a response to the 2005 avian influenza H5N1 threat. The FDA, the CDC and academic investigators have been developing options for active post-marketing observational collection of safety data that together comprise a pharmacovigilance toolkit. The elements of this include the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), started in 1990 to collect information from electronic medical records; the FDA Sentinel initiative launched in 2008 and its Post-licensure Rapid Immunization Safety Monitoring (PRISM) programme activated in 2016, which integrates administrative and claims data from hospitals and insurance companies, and Medicaid and Medicare databases.

The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), started in 1990, is a system for passively collecting data from health care providers, manufacturers and the public. Although observational data are inherently biased, they can support data obtained from randomized controlled trials, especially in cases of accelerated approval as may be expected during a public health crisis like an influenza pandemic. For example, during the 2009 pandemic, accelerated licensure was granted to a high-dose trivalent influenza vaccine (independent of the H1N1 outbreak) for use in the elderly based on superior induction of HAI as a surrogate of efficacy209. Part of the licensure agreement was for the manufacturer to carry out post-marketing efficacy studies. A 31,000-person randomized controlled trial subsequently showed that the high-dose influenza vaccine demonstrated clear superior efficacy relative to the standard-dose vaccine210.

Using the Medicare database, an observational study design to control for bias in health-seeking behaviour and other factors provided supportive data that efficacy was achieved211. Another way to use observational data to assess influenza vaccine effectiveness and avoid most bias is to use a ‘test-negative’ case–control trial design212. Subjects with laboratory-proven influenza are assigned as cases and those who test negative are designated controls. The frequency of vaccination in each group can be used to accurately estimate vaccine efficacy213, especially if factors like the method of diagnosis, vaccine type and influenza strain are specified.

Outlook

Despite moderate-to-low efficacy, cumbersome manufacturing processes and long lead times for annual strain reformulation, the current production system of seasonal influenza vaccines has been relatively unchanged over the past 40 years. Advances across the fields of structural biology, influenza virology and immunity have set the stage for major advances towards improved seasonal and universal influenza vaccines. The influenza vaccine field’s acceptance of these technological advances is only the first step towards worldwide practical implementation of next-generation vaccines. Meaningful and lasting advances in the influenza vaccine field are now achievable, but they depend upon leveraging expertise, communication and cooperation from stakeholders across many disciplines, from funding agencies to basic scientists, epidemiologists, regulators, manufacturers and the public.

Seasonal influenza vaccine production remains an enormous challenge for manufacturers as the vaccines must be produced and released 6 months after the WHO announces the vaccine strains for the following season in a given hemisphere. Currently, there are three different production technologies approved for influenza vaccines: egg-based, cell-based and recombinant proteins. The majority of the licensed vaccines are made using embryonic chicken eggs, and even though this production system has remained unchanged for decades, it is still the only method that can meet the current annual need of seasonal influenza vaccine for the global population. Five hundred million doses are generated annually but could potentially produce 1.5 billion seasonal and 6.4 billion pandemic doses214. Vaccines produced from cell culture were first approved by the FDA in 2012 (ref.215) and a synthetic HA vaccine was subsequently approved in 2013 (ref.216). This recombinant protein-based approach allows a process that does not require virus propagation and can be run on a large scale once the appropriate infrastructure is in place. Together with the recent advances in high-cell density, perfusion continuous flow processing217, this approach opens the door to producing next-generation subunit protein vaccines and meeting the increasing demand for safe, affordable and effective influenza vaccines.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jeffrey C. Boyington (Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health) for generating the HA structural model and Stefan Köester (Sanofi) for the HA and NA phylogenetic trees and the NA model. They also thank Brian DelGiudice (Sanofi) for assistance in manuscript preparation.

Glossary

- Influenza

A contagious respiratory disease caused by influenza viruses.

- Haemagglutinin

(HA). A homotrimeric glycoprotein found on the surface of influenza virus particles responsible for the recognition of the host target cell through the binding of sialic acid-containing receptors.

- Neuraminidase

(NA). A homotetrameric glycoprotein found on the surface of influenza virus particles that facilitates the virus’ release from the host cell.

- Matrix protein 2

(M2). A homotetrameric protein that serves as a proton-selective channel essential for maintaining a pH gradient across the viral membrane during host cell entry and is vital for virus replication.

- Nucleoprotein

(NP). A viral structural protein that encapsidates negative-strand viral RNA to allow RNA transcription, replication and packaging.

- Haemagglutination inhibition

(HAI). The haemagglutination inhibition assay is a method to quantify the relative titre of viruses or determine the concentration of antiserum or antibody required to prevent haemagglutination, a process in which influenza viruses bind and agglutinate red blood cells in cell culture.

- Virus-like particle

A molecule that closely resembles viruses but lacks certain viral genetic materials to be infectious.

- Vaccine adjuvant

An immunostimulant used with an antigen to improve its immunogenicity.

- Pandemic influenza

An epidemic caused by worldwide spread of a new influenza virus that infects a large portion of the population globally.

- Toll-like receptor

A family of type I transmembrane pattern recognition receptors that sense foreign pathogens or endogenous danger signals and play a central role in early innate immune response.

- Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

An adaptive immune response by which specific antibodies bind to foreign antigens and, in turn, recruit effector cells to lyse target cells.

Competing interests

C.-J.W., J.S., and G.J.N. are employees and stock owners of Sanofi, whose subsidiary Sanofi-Pasteur is a major influenza vaccine producer and has issued patents and pending filed patent applications on various influenza vaccine technologies. C.-J.W and G.J.N. are inventors of gene-based and nanoparticle-based influenza vaccines that have been filed by either Sanofi or the US government. J.R.M. and B.S.G. are employees of the US government, which has issued patents and filed patent applications on various vaccines including ferritin nanoparticle-based influenza vaccines mentioned in this article. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

CDC: Past seasons vaccine effectiveness estimates: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/past-seasons-estimates.html

CDC: United States influenza vaccines 2019–2020: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccines.htm

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Seasonal Influenza Vaccines: https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/prevention-and-control/vaccines/types-of-seasonal-influenza-vaccine

WHO: Influenza vaccine viruses and reagents: https://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/en/

Change history

3/13/2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

- 1.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012;12:36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewnard JA, Cobey S. Immune history and influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccines. 2018;6:28. doi: 10.3390/vaccines6020028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness, 2004–2018https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/past-seasons-estimates (CDC, 2019).

- 4.Erbelding EJ, et al. A universal influenza vaccine: the strategic plan for the national institute of allergy and infectious diseases. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;218:347–354. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabel GJ, Fauci AS. Induction of unnatural immunity: prospects for a broadly protective universal influenza vaccine. Nat. Med. 2010;16:1389–1391. doi: 10.1038/nm1210-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paules CI, Fauci AS. Influenza vaccines: good, but we can do better. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;219:S1–S4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paules CI, Marston HD, Eisinger RW, Baltimore D, Fauci AS. The pathway to a universal influenza vaccine. Immunity. 2017;47:599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paules CI, McDermott AB, Fauci AS. Immunity to influenza: catching a moving target to improve vaccine design. J. Immunol. 2019;202:327–331. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1890025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbey-Martin C, et al. An antibody that prevents the hemagglutinin low pH fusogenic transition. Virology. 2002;294:70–74. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekiert DC, et al. Cross-neutralization of influenza A viruses mediated by a single antibody loop. Nature. 2012;489:526–532. doi: 10.1038/nature11414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong M, et al. Antibody recognition of the pandemic H1N1 influenza virus hemagglutinin receptor binding site. J. Virol. 2013;87:12471–12480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01388-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause JC, et al. Human monoclonal antibodies to pandemic 1957 H2N2 and pandemic 1968 H3N2 influenza viruses. J. Virol. 2012;86:6334–6340. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07158-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause JC, et al. A broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibody that recognizes a conserved, novel epitope on the globular head of the influenza H1N1 virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 2011;85:10905–10908. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00700-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee PS, et al. Receptor mimicry by antibody F045-092 facilitates universal binding to the H3 subtype of influenza virus. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3614. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee PS, et al. Heterosubtypic antibody recognition of the influenza virus hemagglutinin receptor binding site enhanced by avidity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17040–17045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212371109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohshima N, et al. Naturally occurring antibodies in humans can neutralize a variety of influenza virus strains, including H3, H1, H2, and H5. J. Virol. 2011;85:11048–11057. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05397-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt AG, et al. Preconfiguration of the antigen-binding site during affinity maturation of a broadly neutralizing influenza virus antibody. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:264–269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218256109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittle JR, et al. Broadly neutralizing human antibody that recognizes the receptor-binding pocket of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:14216–14221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111497108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu R, et al. A recurring motif for antibody recognition of the receptor-binding site of influenza hemagglutinin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:363–370. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida R, et al. Cross-protective potential of a novel monoclonal antibody directed against antigenic site B of the hemagglutinin of influenza A viruses. PLOS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000350. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corti D, et al. A neutralizing antibody selected from plasma cells that binds to group 1 and group 2 influenza A hemagglutinins. Science. 2011;333:850–856. doi: 10.1126/science.1205669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dreyfus C, Ekiert DC, Wilson IA. Structure of a classical broadly neutralizing stem antibody in complex with a pandemic H2 influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 2013;87:7149–7154. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02975-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dreyfus C, et al. Highly conserved protective epitopes on influenza B viruses. Science. 2012;337:1343–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1222908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekiert DC, et al. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science. 2009;324:246–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1171491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekiert DC, et al. A highly conserved neutralizing epitope on group 2 influenza A viruses. Science. 2011;333:843–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1204839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friesen RH, et al. A common solution to group 2 influenza virus neutralization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:445–450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319058110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu Y, et al. A broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibody reveals ongoing capacity of haemagglutinin-specific memory B cells to evolve. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12780. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joyce MG, et al. Vaccine-induced antibodies that neutralize group 1 and group 2 influenza A viruses. Cell. 2016;166:609–623. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kallewaard NL, et al. Structure and function analysis of an antibody recognizing all influenza A subtypes. Cell. 2016;166:596–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashyap AK, et al. Combinatorial antibody libraries from survivors of the Turkish H5N1 avian influenza outbreak reveal virus neutralization strategies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5986–5991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801367105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura G, et al. An in vivo human-plasmablast enrichment technique allows rapid identification of therapeutic influenza A antibodies. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okuno Y, Isegawa Y, Sasao F, Ueda S. A common neutralizing epitope conserved between the hemagglutinins of influenza A virus H1 and H2 strains. J. Virol. 1993;67:2552–2558. doi: 10.1128/JVI.67.5.2552-2558.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sui J, et al. Structural and functional bases for broad-spectrum neutralization of avian and human influenza A viruses. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Throsby M, et al. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against H5N1 and H1N1 recovered from human IgM+ memory B cells. PLOS ONE. 2008;3:e3942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Y, et al. A potent broad-spectrum protective human monoclonal antibody crosslinking two haemagglutinin monomers of influenza A virus. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7708. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang TT, et al. Broadly protective monoclonal antibodies against H3 influenza viruses following sequential immunization with different hemagglutinins. PLOS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000796. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soema PC, Kompier R, Amorij JP, Kersten GF. Current and next generation influenza vaccines: formulation and production strategies. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015;94:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunkle LM, et al. Efficacy of recombinant influenza vaccine in adults 50 years of age or older. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:2427–2436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sebastian S, Lambe T. Clinical advances in viral-vectored influenza vaccines. Vaccines. 2018;6:E29. doi: 10.3390/vaccines6020029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajao DS, Perez DR. Universal vaccines and vaccine platforms to protect against influenza viruses in humans and agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:123. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tong S, et al. New world bats harbor diverse influenza A viruses. PLOS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003657. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirst GK. The quantitative determination of influenza virus and antibodies by means of red cell agglutination. J. Exp. Med. 1942;75:49–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.75.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hobson D, Curry RL, Beare AS, Ward-Gardner A. The role of serum haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody in protection against challenge infection with influenza A2 and B viruses. J. Hyg. 1972;70:767–777. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400022610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Z, Zhou H, Jin H. The impact of key amino acid substitutions in the hemagglutinin of influenza A (H3N2) viruses on vaccine production and antibody response. Vaccine. 2010;28:4079–4085. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raymond DD, et al. Influenza immunization elicits antibodies specific for an egg-adapted vaccine strain. Nat. Med. 2016;22:1465–1469. doi: 10.1038/nm.4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilkinson K, et al. Efficacy and safety of high-dose influenza vaccine in elderly adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2017;35:2775–2780. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JKH, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccination for older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert. Rev. Vaccines. 2018;17:435–443. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1471989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camilloni B, Basileo M, Di Martino A, Donatelli I, Iorio AM. Antibody responses to intradermal or intramuscular MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccines as evaluated in elderly institutionalized volunteers during a season of partial mismatching between vaccine and circulating A(H3N2) strains. Immun. Ageing. 2014;11:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Camilloni B, Basileo M, Valente S, Nunzi E, Iorio AM. Immunogenicity of intramuscular MF59-adjuvanted and intradermal administered influenza enhanced vaccines in subjects aged over 60: a literature review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2015;11:553–563. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1011562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Darricarrere N, et al. Development of a pan-H1 influenza vaccine. J. Virol. 2018;92:e01349–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01349-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carter DM, et al. Design and characterization of a computationally optimized broadly reactive hemagglutinin vaccine for H1N1 influenza viruses. J. Virol. 2016;90:4720–4734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03152-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elliott STC, et al. A synthetic micro-consensus DNA vaccine generates comprehensive influenza A H3N2 immunity and protects mice against lethal challenge by multiple H3N2 viruses. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018;29:1044–1055. doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giles BM, Ross TM. A computationally optimized broadly reactive antigen (COBRA) based H5N1 VLP vaccine elicits broadly reactive antibodies in mice and ferrets. Vaccine. 2011;29:3043–3054. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ping X, et al. Generation of a broadly reactive influenza H1 antigen using a consensus HA sequence. Vaccine. 2018;36:4837–4845. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong TM, et al. Computationally optimized broadly reactive hemagglutinin elicits hemagglutination inhibition antibodies against a panel of H3N2 influenza virus cocirculating variants. J. Virol. 2017;91:e01581-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01581-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen MW, et al. Broadly neutralizing DNA vaccine with specific mutation alters the antigenicity and sugar-binding activities of influenza hemagglutinin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:3510–3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019744108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Florek NW, et al. A modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine vector expressing a mosaic H5 hemagglutinin reduces viral shedding in rhesus macaques. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0181738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamlangdee A, Kingstad-Bakke B, Anderson TK, Goldberg TL, Osorio JE. Broad protection against avian influenza virus by using a modified vaccinia Ankara virus expressing a mosaic hemagglutinin gene. J. Virol. 2014;88:13300–13309. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01532-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei CJ, et al. Induction of broadly neutralizing H1N1 influenza antibodies by vaccination. Science. 2010;329:1060–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.1192517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ledgerwood JE, et al. DNA priming and influenza vaccine immunogenicity: two phase 1 open label randomised clinical trials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011;11:916–924. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70240-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Atsmon J, et al. Priming by a novel universal influenza vaccine (Multimeric-001)—a gateway for improving immune response in the elderly population. Vaccine. 2014;32:5816–5823. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Santos JJS, et al. Development of an alternative modified live influenza B virus vaccine. J. Virol. 2017;91:e00056-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00056-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ducatez MF, et al. Low pathogenic avian influenza (H9N2) in chicken: evaluation of an ancestral H9-MVA vaccine. Vet. Microbiol. 2016;189:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Florek NW, et al. Modified vaccinia virus Ankara encoding influenza virus hemagglutinin induces heterosubtypic immunity in macaques. J. Virol. 2014;88:13418–13428. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01219-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hessel A, et al. MVA vectors expressing conserved influenza proteins protect mice against lethal challenge with H5N1, H9N2 and H7N1 viruses. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e88340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lillie PJ, et al. Preliminary assessment of the efficacy of a T-cell-based influenza vaccine, MVA-NP + M1, in humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:19–25. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boyd AC, et al. Towards a universal vaccine for avian influenza: protective efficacy of modified vaccinia virus Ankara and adenovirus vaccines expressing conserved influenza antigens in chickens challenged with low pathogenic avian influenza virus. Vaccine. 2013;31:670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crosby CM, et al. Replicating single-cycle adenovirus vectors generate amplified influenza vaccine responses. J. Virol. 2017;91:e00720. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00720-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wesley RD, Tang M, Lager KM. Protection of weaned pigs by vaccination with human adenovirus 5 recombinant viruses expressing the hemagglutinin and the nucleoprotein of H3N2 swine influenza virus. Vaccine. 2004;22:3427–3434. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim SH, Paldurai A, Samal SK. A novel chimeric newcastle disease virus vectored vaccine against highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Virology. 2017;503:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Q, et al. Newcastle disease virus-vectored H7 and H5 live vaccines protect chickens from challenge with H7N9 or H5N1 avian influenza viruses. J. Virol. 2015;89:7401–7408. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00031-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vander Veen RL, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of an alphavirus replicon-based swine influenza virus hemagglutinin vaccine. Vaccine. 2012;30:1944–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vander Veen RL, et al. Haemagglutinin and nucleoprotein replicon particle vaccination of swine protects against the pandemic H1N1 2009 virus. Vet. Rec. 2013;173:344. doi: 10.1136/vr.101741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Antrobus RD, et al. Clinical assessment of a novel recombinant simian adenovirus ChAdOx1 as a vectored vaccine expressing conserved influenza A antigens. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:668–674. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hubby B, et al. Development and preclinical evaluation of an alphavirus replicon vaccine for influenza. Vaccine. 2007;25:8180–8189. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kreijtz JH, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a modified-vaccinia-virus-Ankara-based influenza A H5N1 vaccine: a randomised, double-blind phase 1/2a clinical trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014;14:1196–1207. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70963-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liebowitz D, Lindbloom JD, Brandl JR, Garg SJ, Tucker SN. High titre neutralising antibodies to influenza after oral tablet immunisation: a phase 1, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015;15:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pardi N, et al. Nucleoside-modified mRNA immunization elicits influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3361. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05482-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Low JG, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a virus-like particle pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccine: results from a double-blinded, randomized phase I clinical trial in healthy Asian volunteers. Vaccine. 2014;32:5041–5048. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pillet S, et al. A plant-derived quadrivalent virus like particle influenza vaccine induces cross-reactive antibody and T cell response in healthy adults. Clin. Immunol. 2016;168:72–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Valero-Pacheco N, et al. Antibody persistence in adults 2 years after vaccination with an H1N1 2009 pandemic influenza virus-like particle vaccine. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0150146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fries LF, Smith GE, Glenn GM. A recombinant viruslike particle influenza A (H7N9) vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:2564–2566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1313186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lowell GH, Ziv S, Bruzil S, Babecoff R, Ben-Yedidia T. Back to the future: immunization with M-001 prior to trivalent influenza vaccine in 2011/12 enhanced protective immune responses against 2014/15 epidemic strain. Vaccine. 2017;35:713–715. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van Doorn E, et al. Evaluating the immunogenicity and safety of a BiondVax-developed universal influenza vaccine (Multimeric-001) either as a standalone vaccine or as a primer to H5N1 influenza vaccine: phase IIb study protocol. Medicine. 2017;96:e6339. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Doorn E, et al. Evaluation of the immunogenicity and safety of different doses and formulations of a broad spectrum influenza vaccine (FLU-v) developed by SEEK: study protocol for a single-center, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled clinical phase IIb trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017;17:241. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2341-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hatta Y, et al. M2SR, a novel live influenza vaccine, protects mice and ferrets against highly pathogenic avian influenza. Vaccine. 2017;35:4177–4183. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sarawar S, et al. M2SR, a novel live single replication influenza virus vaccine, provides effective heterosubtypic protection in mice. Vaccine. 2016;34:5090–5098. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kanekiyo M, et al. Self-assembling influenza nanoparticle vaccines elicit broadly neutralizing H1N1 antibodies. Nature. 2013;499:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]